Abstract

Nonlinear optics (NLO) is a fascinating field that explores how intense light interacts with matter. Organic chromophores are regarded as promising materials for nonlinear optics research due to their properties i.e., easy of process, structural versatility, and instant response to NLO effects. Therefore, in current research, a comprehensive investigation was carried out on a series of organic indacenothienothiophene (ITT) based chromophores (AOR and AO1-AO6) to explore their NLO properties through quantum chemical calculations. The DFT and TD-DFT methods at M06/6-311G(d,p) level were employed to investigate the optoelectronic properties of new designed compounds. The parent compound, i.e., AOIC was taken for the designing of the reference molecule (AOR) by substituting one terminal acceptor with donor in AOIC to develop push–pull architecture. The other derivatives (AO1-AO6) were designed via modulation of end-capped acceptor of AOR with benzothiophene (BT) based acceptors. These investigations revealed a red-shift absorption spectra (λmax = 783–848 nm) with reduced HOMO–LUMO energy gap (Egap = 1.741–1.956 eV) in AO1-AO6 as compared to AOR (Egap = 2.040; λmax=743 nm) in chloroform. Significant charge transferred from donor to BT acceptors through ITT core in AO1-AO6 as illustrated by DOS, FMOs and TDM analyses. All entitled compounds (AO1-AO6) exhibited a notable NLO response relative to the AOR. Particularly, AO2 displayed the prominent results like < α > = 2.790 × 10–22 esu, βtotal = 7.027 × 10–27 esu and γtotal = 11.440 × 10–32 esu among all the derivatives. This might be owing to unique optoelectronic characteristics such as lowest Egap (1.741 eV) and hardness (0.871 eV) with highest softness (0.574 eV) and absorption spectrum (820 nm) of AO2. Hence, these calculations illustrated that the end-capped substitution of acceptor moieties with BT acceptors and the incorporation of conjugated donor system played a vital role in improving the NLO aptitude. Overall, these ITT-based derivatives can be considered as potential materials for promising applications in NLO field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear optics (NLO) is related to the study of material’s interactions with intense laser light1. The NLO materials play a significant role in the photonic devices, telecommunication2, holographic imaging3 and optical data storage4 etc. The NLO chromophores demonstrate significant utility across a wide scientific domains including, biophysics, material sciences, solid-state physics, chemical dynamics, medicine and nuclear research5,6. Different materials such as hybrid7, polymer8, organometallic9, organic10 and inorganic compounds11 are widely utilized for NLO applications.

The search for highly efficient and versatile NLO materials has led to significant advancements in organic materials’ field12. Owing to unique characteristics of organic materials over other inorganic and hybrid materials such as structural diversity, lower dielectric constants, flexibility, wide availability, facile synthesis and high NLO coefficients, they are widely utilized for NLO applications13,14,15. The structural flexibility of organic chromophores allows for precise molecular engineering, enabling the fine-tuning of electronic and optical properties to meet specific application requirements16. Among organic frameworks, π-conjugated systems with push–pull farmwork have emerged as a promising platform for designing efficient NLO materials17.

The introduction of a push–pull molecular architecture, a design strategy where electron-donating (push) and electron-accepting (pull) groups are incorporated into the molecule, can significantly enhance the NLO properties organic chromophores. This arrangement intensifies intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) within the molecule, leading to increased polarizability and hyperpolarizability, which are essential for achieving high NLO coefficients18. Creating an effective D–π–A compound involves tailoring the push–pull structural arrangements and evaluating how donor–acceptor (D–A) units influence it19. By systematically varying the donor and acceptor groups and their positions, the optical transparency, response times, and overall NLO performance of the material can be finely tuned20.

Amidst many classes of organic compounds, non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) based NLO chromophores have emerged as promising NLO materials because of their immense flexibility in molecular design, affordability, precise adjustability, impressive molar extinction coefficients, ease of purification, and remarkable absorption capabilities across the visible spectra and near-infrared (NIR)21,22,23. Furthermore, in context of NFAs, the π-conjugation facilitates a substantial charge transfer at donor–acceptor interface, promoting electronic delocalization24. Recent studies have explored various classes of NFAs, such as fused-ring electron acceptors (FREAs), diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP) derivatives, and perylene diimides (PDIs), for their potential in NLO applications. For instance, research on Y6 and its derivatives has provided insights into their unique optical and electronic properties, which are crucial for enhancing NLO responses25,26.

Zhan and coworkers, introduced fused ring electron acceptors (FREAs) by synthesizing the ITIC compound27 in 2015. This FREAs consist of a firm fused-ring core namely indacenothienothiophene (ITT) with aromatic properties, accompanied by alkyl or aryl side chains, and two highly effective electron-accepting groups28,29. A smaller arrangement of fused rings is expanded into a larger configuration of fused rings in a one-way direction, allowing for precise adjustments to electronic characteristics. Additionally, this one-way expansion could result in an uneven molecular arrangement, potentially boosting the molecular dipole moment and dielectric constant. By introducing donor and acceptor groups or modulating the substituents on the IDTT core, the optical properties, such as hyperpolarizability and transparency range, can be effectively tailored, opening new avenues for advanced NLO materials30,31,32,33.

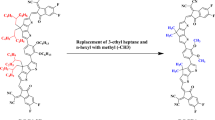

The synthesized parent compound (AOIC)34 comprising A–π–A framework is selected for the structural designing . The parent molecule is comprised of indacenothienothiophene (ITT) as core unit which is fascinating and possesses an ability to exhibit strong third-order NLO effects. Further, the single-crystal structure of its derivatives showed interesting polymorphic behavior which significantly influence their NLO properties. The literature shows that indacenothienothiophene, in combination with strong acceptors and spacer groups can lead to significant push–pull systems35,36. By inspiring the above properties of ITT core, new derivatives (AOR and AO1-AO6) consisted on ITT core are designed for NLO materials. Herein, in AOIC, the bulky groups i.e., 1-hexyl-4-methylbenzene attached to the π-spacer are substituted by methyl (–CH3) to avoid steric hindrance and reduce computational expenses. The parent compound, AOIC, was used as the basis for designing the reference molecule (AOR) by replacing one terminal acceptor in AOIC with a donor to establish a push–pull configuration. Further derivatives (AO1–AO6) were developed by modifying the end-capped acceptor of AOR with BT based acceptors. Literature data illustrated that NLO properties of these derivatives are not reported. After structural modeling, their NLO characteristics are investigated through DFT/TD-DFT approaches. This study represents a step forward in the development of NLO materials and offers potential insights into the theoretical investigation of second order NLO properties due to the advantageous D–π–A arrangement.

Computational procedure

All the quantum chemical calculations were conducted by employing the Gaussian 09 program37 utilizing the DFT approach. For present study, the M06/6-311G(d,p) functional38 was utilized for determining the electronic, absorption spectra and NLO characteristics of the studied compounds.39,40. The triple zeta basis set is efficient in determining the NLO characteristics of the organic molecules therefore, it was employed along with M06 functional41. The ground state geometries of the studied compounds were analyzed by utilizing the Gauss View 6.0 program.42 The frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) investigation was conducted to determine the Egap between the HOMO and LUMO43. The NBO 5.0 program44 was utilized for the natural bond orbitals (NBOs) analysis to determine the interactions between molecular orbitals and their energy of stabilization. Using the PyMOlyze 2.0 program45, the density of states (DOS) data from Gaussian log was interpretated to determine the charge density distribution on molecular orbitals of the designed compounds. The UV-Vis absorption graphs were drawn via the Origin 8.0 software46. Various software like Multiwfn,47 Chemcraft,48 GaussSum49 and Avogadro50 were employed for interpretation and visualization of results from the output files.

Results and discussion

The present research focuses on exploration of the NLO efficiency of newly designed derivatives (AO1-AO6). For this purpose, the A–π–A type configured parent molecule (AOIC) is modified into D–π–A from the reference compound (AOR) by introduction of the donor species at one end. Moreover, other derivatives (AO1-AO6) are formed by altering the peripheral acceptor of the reference derivative (AOR) with different acceptor moieties given in the Fig. 1 to improve their polarity in order to enhance their NLO characteristics. The derivatives (AO1-AO6) have three fragments: (i) donor, (ii) π-linker and (iii) conjugated acceptors. To reduce the computational cost, the bulky group (1-hexyl-4-methylbenzene) is replaced with smaller alkyl groups (–CH3) and one end-capped acceptor with a strong donor i.e., triphenylamine motif in AOIC parent compound34 which is modified into the reference (AOR), (see Fig. 1). In the case of derivatives, the π-spacer and donor moiety (D) of AOR remained the same, while the acceptor is replaced with various strong acceptor groups51 (Fig. 2). The optimized structures of the AOR and AO1-AO6 are shown in the Fig. S1, while their Cartesian coordinates are given in the Tables S1–S7 (Supplementary Information). The DFT/TDDFT computations are performed for the above-mentioned series of fused ring NFAs compounds including the analyses such as the HOMO/LUMO energy gaps, NBOs, UV–Visible, TDM, linear polarizability ⟨α⟩, second and third-order hyperpolarizabilities (βtotal and γtotal). The D–π–A framework in the studied compounds show a strong push–pull architecture that results in stronger ICT properties.

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) analysis

FMOs investigation determines the optoelectronic properties, and chemical stability of a molecule52. Moreover, it assists in determining the charge distribution over HOMO and LUMO. The HOMO demonstrates electron-donating potential, while LUMO displays electron-accepting capacity20. Molecules with larger energy gap (Egap) are identified as harder molecule with lesser reactivity and larger stability. In contrast, materials having lower Egaps are recognized as soft molecules, exhibiting greater reactivity, decreased stability, and higher polarizability53. An inverse relation between Egap and ICT of a molecule is existed i.e., a greater ability of charge transfer results in low Egap values54. The Egap value of any material significantly affects its optoelectronic properties by altering the ICT process. Consequently, the materials with lower Egap value facilitate easier electronic transitions from HOMO to LUMO by promoting greater ICT, resulting in lesser transition energy55. Assuming all these considerations, the Egap = (ELUMO-EHOMO), EHOMO and ELUMO of AOR and AO1-AO6 are calculated and illustrated in Tables 1 and S8.

Table 1 shows that EHOMO of AOR and AO1-AO6 are observed as − 5.319, − 5.301, − 5.339, − 5.315, − 5.333, − 5.301 and − 5.335 eV, respectively. Similarly, their ELUMO are found as − 3.279, − 3.345, − 3.598, − 3.430, − 3.520, − 3.384 and − 3.537 eV, respectively. Moreover, the Egap values of the titled chromophores are found as 2.040, 1.956, 1.741, 1.885, 1.813, 1.917 and 1.798 eV, respectively (Table 1). Herein it is found that the compounds (AO1 and AO5) exhibited almost similar Egap values i.e., 1.956 and 1.917 eV, respectively, which are slightly lesser than compound AOR. The least Egap (1.741 eV) is observed in AO2 due to the electron-withdrawing –NO2 and –CN groups in the acceptor region of this compound (see Fig. 3). Similarly, for compound (AO6), a small Egap value is found as 1.798 eV. The structures of both compounds (AO2 and AO6) are almost similar because of the presence of –NO2 and –CN groups in AO2 and only –CN group in AO6 in their acceptor regions, thus causing strong electron withdrawing inductive effect. Both chromophores exhibit lowest Egap values with higher degree of charge transfer because of these electron withdrawing moieties . Considering compound (AO3), the Egap value is observed as 1.885 eV which is greater as compared to AO2 and AO6 due to presence of trifluoro (–CF3) group at acceptor site which shows lesser electron withdrawing capacity. In case of AO4, the two –SO3H groups along with the two –CN groups conjoining with thiophene ring in the terminal acceptors collectively result in declining the Egap value (1.813 eV). The descending order for Egap is as follow: AOR > AO1 > AO5 > AO3 > AO4 > AO6 > AO2.

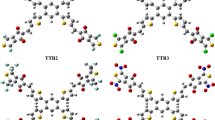

Pictographic display of HOMO–LUMO orbitals of the investigated molecules (AOR and AO1-AO6) drawn with the help of Avogadro software, Version 1.2.0. (http://avogadro.cc/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Accompanying with the orbital (HOMO–LUMO) energies, charge transfer between orbitals are presented with the help of the pictographs in Fig. 3, while, the ICT in HOMO-1, LUMO + 1, HOMO-2 and LUMO + 2 orbitals is presented in Figure S2. These molecular orbitals show the electronic charge densities over HOMOs and LUMOs of the entitled compounds. It is noted that the electronic densities are predominantly concentrated on the donor and to some extent on the π-spacer moiety in case of HOMO. Conversely, in LUMO, the charge tends to shift towards the terminal acceptors via the π-bridge. In this scenario, a larger electronic cloud is primarily observed over the π-spacer and acceptors, and observed little bit over donor unit in all the examined compounds.

A smaller HOMO–LUMO band gap is preferred because it allows electronic transitions at lower energies, enhancing the NLO response by facilitating photon absorption. Moreover, molecules with greater electron density delocalization between the HOMO and LUMO tend to exhibit increased polarizability, leading to stronger NLO effects56,57. Concluding the above discussion, all the designed chromophores exhibit smaller Egap values as compared to the reference chromophore, demonstrating their efficiency towards the photo-electronic materials. The AO2 chromophore might be regarded as the most efficient NLO compound among the designed derivatives owing to its lower band gap.

Natural bond orbitals (NBOs) analysis

The exploration of electronic charge transfer from the electron-donating moiety (HOMO) towards the accepting-moiety (LUMO) of the system is one of the most essential features of the NBOs investigation58,59. Second-order perturbation theory is used to calculate the energy of stabilization60 of molecules by employing the Eq. (1):

Here, i represents donor, j indicates the acceptor and E(2) indicating the energy of stabilization. Moreover, qi, εj, εi and Fi,j characterize the donor orbital occupancy, diagonal and off-diagonal NBOs Fock matrix elements, correspondingly. The NBOs investigation is performed at the M06 level along with 6-311G(d,p) basis set, the major results of representative transitions are shown in Table 2. Furthermore, the other transitions exhibited by the derivatives are recorded in the Tables S9–S15.

Usually, four types of transitions are observed in the studied compounds: π → π*, σ → σ*, LP → π* and LP → σ*. Among all of these, the π → π* transitions are considered the most dominant as they depict the presence of conjugation. The LP → σ* and LP → π* are prominent to some extent, while σ → σ* are considered as feeble transitions due to σ electrons. The highest π → π* transitions are π(C28-C29) → π*(C32-C33) with following stabilization energy values: 34.51, 32.77, 34.75, 33.71, 34.57, 33.02 and 34.48 kcal/mol energy in AOR and AO1-AO6, respectively. While, the lowest energy transitions are π(C61-C63) → π*(C50-C52) in case of AO1, AO3 and AO5 having transition energies as 0.51, 0.53 and 0.52 kcal/mol, respectively. The rest of the studied compounds (AOR, AO2, AO4 and AO6) possess π(C9-C10) → π*(C9-C10) as the lowest energy transition with values as 0.5, 0.52, 0.51 and 0.51 kcal/mol, respectively.

In case of feeble σ → σ* transitions, the most significant excitations with largest transition energies are observed as σ(C32-H34) → σ*(C28-S30) having energy of 10.71, 10.35, 10.51, 10.44, 10.47, 10.38 and 10.46 kcal/mol for AOR and AO1-AO6, respectively. Other transitions with minimal energy levels are also seen as: σ(C3-C9) → σ*(C9-S13)with energy of 0.5 kcal/mol for AOR and AO1-AO4, respectively. Whereas, for AO5 and AO6 compounds, σ(C102-S110) → σ*(C35-C36) and σ(C15-C27) → σ*(C12-S13) transitions are observed with least stabilization energies as 0.5 kcal/mol.

Considering the lone pair transitions of the investigated compounds, the highest LP → π* transitions are observed as LP2(S30) → π*(C16-C17) in AOR and AO1-AO4 with the E(2) values as 28.78, 28.56, 28.70, 8.60 and 28.67 kcal/mol, respectively. Similarly, the significant LP → π* transitions in AO5 and AO6 are LP2(O112) → σ*(C111-O113) and LP2(O72) → σ*(C36-C48) with E(2) as 33.28 and 21.84 kcal/mol, respectively. Similarly, the lowest energy of lone pair transitions include LP2(O78) → σ*(C39-C54) in AOR, with value of 21.32 kcal/mol, while in AO1-AO3, the LP2(O72) → σ*(C36-C48) transitions are observed with 21.5, 21.9 and 21.66 kcal/mol energy values, respectively revealed as the lowest lone pair transitions. The transitions such as LP1(N75) → σ*(C73-C74), LP1(N49) → π*(C50-C52) and LP1(N49) → π*(C61-C63) are noted with least values as 12.61, 18.41 and 18.50 kcal/mol for compounds AO4, AO5 and AO6, respectively. The NBOs analysis reveals that strong ICT and hyper-conjugative interactions play a vital part in stabilizing all these structures as well as provided proof of charge transfer which is essential for potential NLO properties.

Global reactivity parameters (GRPs)

The energies of the HOMO and LUMO are commonly employed as supplementary parameters to elucidate the reactivity and stability of a system61. So, the HOMO–LUMO Egap plays a crucial role in evaluating the chemical reactivity and dynamic stability of molecules62. The determination of the energy values is crucial in the calculation of various global reactivity parameters (GRPs). In this study, a correlation between the Egap values of reference (AOR) and AO1-AO6 molecules and their global reactivity descriptors is established. The GRPs include; global electrophilicity index (ω), electron affinity (EA), global softness (σ), chemical potential (μ), electronegativity (χ), ionization potential (IP) and global hardness (η)63. The Egap is inversely related with the softness and reactivity of the species being investigated64, while showing a direct correlation with the hardness and stability of the compounds. Consequently, the molecules with a higher Egap are seen to exhibit less susceptibility to changes in electronic configuration. The EA and IP values indicate the electron-accepting and electron-donating properties of the compounds, as determined by their corresponding LUMO and HOMO values65. All such parameters are calculated via employing the Eqs. (2)–(9):

As Table 3 reveals that the observed hardness values show a progressive reduction in almost all the derivatives as compared to AOR. Among all the derived chromophores, AO2 displays the minimum results of hardness (0.871 eV) which is in correspondence with its least HOMO–LUMO Egap. Similarly, by comparing the values of IP of reference (AOR) with designed derivatives (AO1-AO6), it can be seen that the ionization potential values increase in the derivatives and maximum value i.e., 5.339 eV is represented by AO2. Correspondingly, the observed pattern of predicted hardness (η) values in all the studied molecules show a reduction precisely according to their Egap values. Hence, the studied chromophores can be ranked in the following order in terms of their decreasing hardness: AOR (1.020) > AO1 (0.978) > AO5 (0.958) > AO3 (0.942) > AO4 (0.906) > AO6 (0.899) > AO2 (0.871) eV, respectively. The global softness (σ) is an additional characteristic that indicates the extent of reactivity of compounds and is also closely linked to their polarizability. The σ values show an increasing trend in the proposed compounds in the order exactly opposite to that of global hardness (η) owing to an inverse relation between them (0.490, 0.511, 0.574, 0.530, 0.551, 0.521 and 0.556 eV−1 in AOR and AO1-AO6 compounds, respectively).

Concluding the above discussion, the compound (AO2) is found as highly reactive molecule owing to its utmost σ value as 0.574 eV−1 and least η as 0.871 eV. So, it might be regarded as the most polarizable entity among all the entitled chromophores. Moreover, the results of GRPs elucidate that all the derived molecules are polarizable and can possess good NLO properties.

UV–Visible analysis

In order to estimate the optoelectronic properties of the studied chromophores (AOR and AO1-AO6), their UV–Visible analysis is executed in the chloroform and gaseous phases by employing the TD-DFT computations at the above-mentioned functional66. This analysis offers a valuable insight towards the possibility of contributing configurations, charge transference and nature of electronic transitions in the studied chromophores67,68. Moreover, the consequences of modulation of terminal acceptor and addition of a donor group on the optical properties of the designed compounds are also studied. By executing the analysis, six lowest singlet–singlet allowed transitions are calculated for AOR and AO1-AO6 and given in the Tables S16–S29. The highest transition wavelengths (λmax) along with their major contributing MO percentages are shown in the Table 4, however, their UV–Visible spectra (in both chloroform and gaseous phase) are depicted in the Fig. 4. It is expected that polar medium involves π → π* and n → π* stabilization states at the suitable energy level69. It has been primarily noted that the UV–Visible results achieved for a polar medium are greatly influenced by the van der waals interactions. Particularly, dipole forces and hydrogen bonding considerably improve the stabilization of the first singlet transition state of systems. Greater polarity in the excited level as compared to ground level prompts bathochromic shifted electronic transitions70.

Simulated absorption spectra of investigated compounds (AOR and AO1-AO6) in the solvent (chloroform) and gaseous phases made by using origin 8.5 version (https://www.originlab.com/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Table 4 clearly depicts that the designed compounds show maximum absorption in the visible region of electromagnetic spectrum. In the chloroform solvent, transition energy calculated for AOR is 1.669 eV at the oscillation strength (fos) of 2.062 and the major MO contribution of 92% from HOMO to LUMO. All the designed chromophores (AO1-AO6) show bathochromic shifts in their absorption wavelengths (λmax) as compared to AOR (743 nm). The highest λmax (873 nm) is noted for AO2 as compared to all the other designed molecules due to the negative inductive (-I) effect induced by strong electronegative groups i.e., cyano (–CN) and nitro (–NO2) groups on the acceptor moiety. Hence, the highest bathochromic shift in AO2 might be due to its unique chemical structure. The following order of λmax is observed in the entitled compounds: AOR (743) < AO1 (783) < AO5 (798) < AO3 (809) < AO4 (840) < AO6 (848) < AO2 (873) in nm in the chloroform (solvent phase). Similarly, the transition energies are observed in the decreasing trend of the λmax as: AOR (1.669) > AO1 (1.583) > AO5 (1.554) > AO3 (1.533) > AO4 (1.475) > AO6 (1.462) > AO2 (1.421) in eV. Their corresponding results of fos are as follows: AOR = 2.062, AO1 = 1.209, AO2 = 1.044, AO3 = 1.178, AO4 = 1.124, AO5 = 1.210, AO6 = 1.106. Among all the titled compounds, 91% molecular orbital contribution is noted in the first transition i.e., H → L in case of AO4 and AO6. While, in compounds (AO1, AO2, AO3 and AO5) the major MO contributions are observed as: H → L (89%), H → L (89%), H → L (90%) and H → L (90%), respectively. It is a common observation that in case of chloroform solvent, the molecular orbital contributions are lessened to some extent as compared to gaseous phase. The reason is that the chloroform is a mid-polar solvent as compared to more polar solvents like water. This suggests a decrease in the energetic contribution of certain molecular orbitals71.

In gaseous phase, the reference (AOR) exhibits λmax = of 688 nm with major H → L (96%) contribution and fos of 1.745 accompanying with the transition energy of 1.803 eV. All the derivatives (AO1-AO6) show greater λmax values than AOR in a range of 725–820 nm. The AO2 compound shows the largest λmax as 820 nm and the smallest E(eV) value of 1.511 eV with a least fos of 0.765 along with the contribution of H → L as 95%. Therefore, AO2 is regarded as the most red-shifted compound, this might be due to the acceptor moiety contains two –NO2 and two –CN both of which are extremely electronegative and exhibit greater –I effect. The λmax of all the titled chromophores are observed in the following ascending order (in nm): AOR (688) < AO1 (723) < AO5 (729) < AO3 (758) < AO4 (796) < AO6 (802) < AO2 (820). The efficacy of NLO materials is also measured from their excitation energies. The transition energy values follow the exactly opposite order of absorption wavelength owing to their inverse relation in eV: AOR (1.803) > AO1 (1.711) > AO5 (1.701) > AO3 (1.635) > AO4 (1.557) > AO6 (1.546) > AO2 (1.511). The oscillation frequency of all the studied compounds is observed in the same trend as the transition energy. The UV–Visible graphs in both phases are displayed in the Fig. 4.

From the above discussion, it can be concluded that the modulation of reference molecule with suitable donor and acceptor moieties resulted in bathochromic shift in the tailored chromophores. The greater charge transference in molecular orbitals and lower excitation energy proved that these compounds are suitable candidates for NLO applications.

Density of states (DOS) analysis

The DOS analysis is employed to reinforce the results of FMOs to assess the electronic properties of all the investigated compounds (AOR and AO1-AO6). Figure 5 illustrates that after substituting the end-capped acceptor groups, distribution of electronic charge density becomes dispersed in various parts of a chromophore in both the HOMO and LUMO. Moreover, the DOS revealed the distribution of electrons from the HOMO to the LUMO72,73. To validate the charge distribution pattern on the molecular orbitals, the DOS percentages on the HOMOs and LUMOs for the studied compounds are calculated59. In DOS pictographs, the values on the left-side depict the HOMOs and values on the right-side represent the LUMOs along the x-axis. The distance between the foremost peaks of HOMO and LUMO represents the Egap of a particular molecule. These calculations and visual representations provide evidence for electron transfer characteristics shown by different acceptor groups and contribute to providing deeper insights of electronic properties of the chromophores under investigation. This study categorizes the entitled chromophores into three separate segments: donor, acceptor and π-spacer regions (Fig. 5). Each segment is individually analyzed to assess its contribution towards the DOS distribution. In this representation, the acceptor, donor and π-spacer segments are distinguished by green, red and blue curved lines, respectively. These graphical representations provide empirical evidence and clearly reveal the charge transfer phenomenon in the investigated systems. Table S30 presents the percentages of the DOS of the studied compounds.

DOS graphs of AOR and AO1-AO6 compounds drawn by utilizing PyMOlyze 1.1 version (https://sourceforge.net/projects/pymolyze/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

The donor’s electronic contribution in the HOMO for AOR and AO1-AO6 is recorded as 0.3, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1 and 0.1%, respectively, whereas, its contribution for the LUMO is found as 0.2, 0.5, 0.1, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5 and 0.5%, respectively. Likewise, for AOR and AO1-AO6, the contribution of the π-bridge for HOMO is observed as 55.6, 27.9, 23.2, 27.7, 26.4, 27.5 and 25.6%, while, for the LUMO, the following contributions are observed: 16.3, 47.8, 10.6, 48.4, 49.5, 48.6 and 50.0%, correspondingly. The charge distribution on acceptor moiety in the entitled compounds at HOMO are investigated as: 44.0, 71.9, 76.7, 72.2, 73.4, 72.4 and 74.3%, whereas, for LUMO are found as: 83.5, 51.8, 89.3, 51.1, 50.1, 50.9 and 49.5%, respectively. Moreover, DOS spectra revealed that the maximum electronic density of HOMO and LUMO is located over the donor and π-spacer as depicted by red and blue high peaks. Conclusively, DOS analysis indicates charge delocalization and a substantial transfer of charge from the electron-rich region to the electron-withdrawing end-capped moiety across the π-bridge. This observation establishes a structural framework conducive to efficient charge transport.

Transition density matrix (TDM)

The transition density matrix (TDM) is a helpful tool for examining transition processes74 and the rate of ICT in a conjugated system. It provides a visual representation of interactions between acceptor and donor components in an excited state75 using three-dimensional plots with color distinctions23. The TDM approach is essential for understanding phenomena related to electronic excitation and electron–hole localization73,76 in specific regions of the compounds under consideration. The TDM calculations for all the entitled compounds (AOR and AO1-AO6) are performed at M06/6-311G(d,p) level. In this study, hydrogen contribution is neglected because hydrogen atoms have such a minimal impact on the transitions.

To simplify the calculations, the structures of studied chromophores (AOR and AO1-AO6) are categorized into three distinct components: acceptor (A), π-spacer and donor (D). The π-bridge works as a pathway to facilitate the charge transfer from peripheral donor to end-capped acceptor moiety. Based on the TDM heat maps, it is observed that the derivatives (AO1-AO6) effectively transmit the electronic charge diagonally from the donor to the acceptor via the π-bridge without any charge trapping by indicating charge coherence. The results shown in the Fig. 6 demonstrate that the transmission of electrons from the π-spacer to the acceptor counterparts proceeds without any interruption. As a result, the acceptor moiety shows a higher electronic charge density than the donor moiety. This distribution of electronic charge density signifies successful charge transference in the investigated molecules.

TDM plots of reference (AOR) and derivatives (AO1-AO6) drawn with the help of Multiwfn 3.7software (http://sobereva.com/multiwfn/). All out put files of designed compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) map is a valuable tool in computational chemistry used to visualize the charge distribution and electrostatic potential around a molecule. It helps in understanding how molecules interact with each other77,78,79,80. The MEP analysis performed for AOR and its analogs (AO1-AO6) utilizing the selected functional, illustrated in the Fig. 7, provides insights into the reactivity patterns of these molecules. The plot reveals that the primary regions marked in red are predominantly located around the oxygen atoms. These areas signify higher electrostatic potential and highlight regions with an increased likelihood for electrophilic attacks due to their electron deficiency. On the other hand, regions depicted in blue and green, which demonstrate more positive potential, are predominantly situated on carbon and hydrogen atoms. These areas are thus identified as subject to nucleophilic reactions, given their relative electron richness and potential to attract electron-poor reagents or species. This analysis, therefore, elucidates the molecular regions most inclined towards specific chemical interactions, offering valuable information for predicting and understanding the chemical behavior of these molecules.

Non-linear optical (NLO) analysis

A captivating interest arises in the field of NLO owing to unique properties and potential applications which the NLO materials offer in various technological domains. These materials possess versatile applications in the fields such as telecommunication, optoelectronics, data storage and signal processing81. The organic molecules are widely investigated in this field as compared to the inorganic compounds due to their extensive π-conjugated systems82. Moreover, a push–pull mechanism is significant for generating the NLO response which is particularly dependent upon the D-π-A framework of organic molecules83. The electronic properties of a compound directly influence its dipole moment (μtotal), linear polarizability 〈α〉, and hyper-polarizabilities i.e., βtotal and γtotal84. These NLO parameters of the entitled chromophores (AOR and AO1-AO6) are examined, and the major results are presented in the Table 5, while Tables S31 and S32 contain other values including their tensors. The above-mentioned properties are computed using the Eqs. (10)–(13).

Equation (10) is used to get the dipole moment85 of all the entitled chromophores.

Equation (11) is also used to calculate linear polarizability, denoted as 〈α〉86.

The magnitude of total first hyperpolarizability87 is measured with the help of the Eq. (12).

Where, the βx = βxxx + βxyy + βxzz, βy=βyyy + βxxy + βyzz and βz = βzzz + βxxz + βyyz.

Second hyperpolarizability88 is calculated by using the Eq. (13).

Here, \({\gamma }_{i}= \frac{1}{15 }\sum_{j}({\gamma }_{ijji}+{\gamma }_{ijij}+{\gamma }_{iijj}) i,j = \{x, y, z\}\)

The dipole moment (μtotal) is a property which is strongly influenced by the electronegativity difference between the atoms. It is calculated by finding the product of the charges and the distance separating them. In studied chromophores, the y and z-axes tensors show lesser contribution in dipole moment, while the tensor component μx shows a substantial contribution to the total dipole moment values of AOR and AO1-AO6 (see Table S31). The compound (AO4) exhibits the highest dipole moment among all the designed derivatives i.e., 18.076 D. The increasing trend of dipole moment of the investigated compounds can be written as follows: AO5 < AO1 < AO3 < AO6 < AOR < AO2 < AO4.

The linear polarizability, denoted as 〈α〉 is linked to the ICT process. This process takes place from the donor (D) portion to the acceptor (A) unit via π-linkers. When compared to all other tensor components, the average polarizability results show the dominated values along x-axis which exhibit the maximum contribution. It is noted that all the designed derivatives possess higher values of 〈α〉 than AOR. Among the reported series of designed chromophores, the first derivative i.e., AO1 displays the smallest polarizability value (2.63 × 10–22 esu). Contrarily, AO2 exhibits the highest polarizability as 2.790 × 10–22 esu. The decreasing order for 〈α〉 is founds as follows: AO2 > AO4 > AO6 > AO5 > AO3 > AO1 > AOR.

The first hyperpolarizability (βtotal) is also a crucial factor in assessing the NLO behavior of a chromophore. The calculated βtotal values for the tailored compounds (AOR and AO1-AO6) are found as: 5.196, 4.667, 7.027, 5.430, 6.248, 5.089 and 6.394 × 10–27 esu, respectively (see Table 5). The maximum results of βtotal (7.027 × 10–27 esu) are displayed by AO2 derivative. Similarly, the second hyperpolarizability (γtotal) for the investigated chromophores is also determined using the same methodology. Based on the acquired data, it is evident that the γtotal tensor component along the x-axis shows the most significant contribution to the overall γtotal values in all the designed compounds. Among all the derived chromophores, AO2 shows the highest γtotal value of 11.44 × 10–32 esu, while AO1 exhibits the lowest value as 6.556 × 10–32 esu. These remarkable NLO responses of the currently designed chromophores denote the significance of these molecules for potential NLO applications in the future.

A comparison of dipole moment of the derived molecules (AO1-AO6) with standard reference para-nitroaniline (1.373 D) shows that their μtotal are 13, 10, 13, 11, 13, 13, 9 and 13 times higher than para-nitroaniline. Similarly, the results of βtotal of derived molecules (AOR and AO1-AO6) are observed to be 803, 721, 1086, 842, 967, 788 and 988 times greater than para-nitroaniline (6.46 × 10–30 esu). Moreover, the results of γtotal of AO1-AO6 are observed to be 9301, 9010, 15,699, 10,725, 12,934, 9966 and 13,493 times greater when compared with para-nitroaniline (7.29 × 10–36 esu)89.

The second-harmonic generation (SHG) with β(− 2ω;ω,ω) the electro-optic Pockel’s effect (EOPE) with β(− ω;ω,0)90 are both wavelength and time dependent factors. The EOPE values are largely enhanced as compared to the static first hyperpolarizabilities values of AOR and AO1-AO6 chromophores. At 1907.21 nm the β (− ω;ω,0) and β (− 2ω;ω,ω) values are in the range of 5.608 × 10–27 to 9.077 × 10–27 and 1.463 × 10–26 to 4.976 × 10–26 esu, respectively, whereas the response is reduced (4.667 × 10–27 to 7.027 × 10−27esu) at static (0.00 nm) wavelength. All the entitled chromophores having larger SHG and EOPE values at 1907.21 nm, indicating that the resonant enhancement of these chromophores takes place in the wavelength. chromophore AO2 shows the best value of SHG and EOPE at 1907.21 nm which is 4.976 × 10–26 and 9.077 × 10–27 esu (Table 6).

Other factors, such as the dc-Kerr effect i.e., γ(− ω; ω,0,0) and electric field induced second harmonic generation (ESHG) i.e., γ(− 2ω; ω,ω,0)91 arise in response to the application of a time-dependent electric field. The calculated results are given in Table 7, where all the designed derivatives show large dc-Kerr effect and ESHG values at specific frequency. Enormously higher γ(− ω; ω,0,0) and γ(− 2ω; ω,ω,0) values at 1907.21 nm are observed for AO2 derivative i.e., 19.29 × 10–32 and − 26.99 × 10–31 respectively, (see Table 7). This indicates that both γ(− ω; ω,0,0) and γ(− 2ω; ω,ω,0) values can be remarkably enhanced at higher wavelengths for these derivatives.

Additionally, a comparative study has been conducted between designed chromophores (AO2 and AO6) and literature reported compounds (a, b, c & d)92 (CPTD7 & CPTD8)93, (DCPPC & DFPPC)94, (DCTM6)95 and (CTMFD2)96. The βtot values showed that AO2 is 21.8, 4.2, 10, 4, 5.5, 5.9, 1.7 and 1.5 times greater than compounds a, b, c, d, CPTD7, CPTD8, DCTM6 and CTMFD2, respectively. Further, AO6 is 19.8, 3.8, 9.4, 3.7, 5, 5.4, 1.6 and 1.3 times greater than compounds above-mentioned compounds. Similarly, the nonlinear γtot values of AO2 is observed to be 3.1, 2.8, 3727, 3520, 51.4 and 25.4 times and AO6 is 2.6, 2.4, 3202.6, 3023, 44.2 and 21.8 times greater than CPTD7, CPTD8, DCPPC, DFPPC, DCTM6 and CTMFD2, respectively.

Conclusion

Herein, ITT-based organic derivatives (AOR and AO1–AO6) are designed through structural modulation by using BT based end-capped electron-accepting moieties to achieve potential NLO materials. The influence of various acceptors on the NLO response of entitled derivatives is investigated via quantum chemical analyses. The acceptor groups are found to have a promising impact on the D-π-A framework which resulted in the derivatives exhibiting improved optoelectronic properties as compared to the reference compound (AOR). The FMOs results shows that the Egap for designed molecules (1.956–1.741 eV) is found much lower than the AOR (2.040 eV). Further, the TDM and DOS analyses also support the FMOs results as significant charge transfer from donor to acceptor moiety is observed. All derivatives showed wide absorption band particularly, AO2 exhibited the most red-shifted value (λmax = 820 nm), accompanied with lowest transitional energy of 1.511 eV. Similarly, due to the presence of highly electronegative groups, such as NO2 and CN in AO2, it shows the least Egap of 1.741 eV. NBOs investigation reveales that the hyper-conjugation and resonance plays significant role in the stabilization of the studied chromophores. NLO study reveals that all chromophores exhibit significant NLO response as compare to standard p-NA compound. Particularly, AO2 exhibit the highest values of < α > = 2.790 × 10–22 esu, βtotal = 7.027 × 10–27 esu and γtotal = 11.44 × 10–32 esu among all the derivatives. Conclusively, the designed chromophores possess high value of hyperpolarizabilities and exhibit bathochromic shifts because of strong electron acceptor moieties. The designed molecules with good NLO properties may be used as the reasonable candidates in optical device.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Shalin, N. I., Fominykh, O. D. & Balakina, M. Y. Effect of acceptor moieties on static and dynamic first hyperpolarizability of azobenzene chromophores. Chem. Phys. Lett. 717, 21–28 (2019).

Muhammad, S. et al. First principles study for the key electronic, optical and nonlinear optical properties of novel donor-acceptor chalcones. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 72, 58–69 (2017).

Kumar, S. & Koh, J. Synthesis, physiochemical and optical properties of chitosan based dye containing naphthalimide group. Carbohyd. Polym. 94(1), 221–228 (2013).

Shkir, M. et al. Optical spectroscopy, crystalline perfection, etching and mechanical studies on P-Nitroaniline (PNA) single crystals. Opt. Mater. 36(3), 675–681 (2014).

Vidya, V. M., Pola, S. & Chetti, P. Optoelectronic and charge transport properties of DnA type 1, 3, 5-triazine derivatives: A combined experimental and DFT Study. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 245, 118940 (2021).

Raavi, S. S. K. Ultrafast Intramolecular Charge Transfer Dynamics and Nonlinear Optical Properties of Phenothiazine-Based Push–Pull Zinc Porphyrin (2022).

Janjua, M. R. S. A. et al. Prediction of remarkably large second-order nonlinear optical properties of organoimido-substituted hexamolybdates. J. Phys. Chem. A 113(15), 3576–3587 (2009).

Kumar, S. et al. Preparation, characterization, and optical properties of a chitosan-anthraldehyde crosslinkable film. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 115(5), 3056–3062 (2010).

Zhang, Y. & Champagne, B. Theoretical insight into the second-order NLO response of the bis {4-[2-(4-Pyridyl) Ethenyl] Benzoato}-Zinc (II) metal-organic framework. J. Phys. Chem. C 116(41), 21973–21981 (2012).

Champagne, B., Guthmuller, J., Perreault, F. & Soldera, A. Theoretical design of the molecular structure of bent-core mesogens with large second-order nonlinear optical properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 116(13), 7552–7560 (2012).

Liu, C.-G. et al. Second-order nonlinear optical properties of transition-metal-trisubstituted polyoxometalate- diphosphate complexes: A donor- conjugated bridge- acceptor paradigm for totally inorganic nonlinear optical materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 113(45), 19672–19676 (2009).

Shafiq, I. et al. Exploring the impact of end-capped moieties on nonlinear optical response in d-π-a configurated based organoboron derivatives: A DFT/TD-DFT study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1238, 114727 (2024).

Khalid, M. et al. Enriching NLO efficacy via designing non-fullerene molecules with the modification of acceptor moieties into ICIF2F: An emerging theoretical approach. RSC Adv. 12(21), 13412–13427. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA01127A (2022).

Muhammad, S. et al. Synthesis, characterisation, optical and nonlinear optical properties of thiazole and benzothiazole derivatives: A dual approach. Mol. Simul. 44(15), 1191–1199. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927022.2018.1475737 (2018).

Srinivas, K., Prabhakar, C., Sitha, S., Bhanuprakash, K. & Rao, V. J. Enhanced molecular first hyperpolarizability in S-triazine derivatives: Combined experimental and computational studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1075, 118–123 (2014).

Jiang, M. & Fang, Q. Organic and semiorganic nonlinear optical materials. Adv. Mater. 11(13), 1147–1151 (1999).

Shafiq, I. et al. Introducing the various electron withdrawing functions in trigging the optical nonlinearity of benzodithiophene based chromophores: A quantum chemical approach. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27(6), 101767 (2023).

Khalid, M. et al. Promising impact of push-pull configuration into designed octacyclic naphthalene-based organic scaffolds for nonlinear optical amplitudes: A quantum chemical approach. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20104 (2023).

Mahmood, R., Janjua, M. R. S. A. & Jamil, S. DFT molecular simulation for design and effect of core bridging acceptors (BA) on NLO response: First theoretical framework to enhance nonlinearity through BA. J. Cluster Sci. 28, 3175–3183 (2017).

Khalid, M. et al. Structural modulation of π-conjugated linkers in D-π-A dyes based on triphenylamine dicyanovinylene framework to explore the NLO properties. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8(8), 210570 (2021).

Lin, Y. & Zhan, X. Non-fullerene acceptors for organic photovoltaics: An emerging horizon. Mater. Horiz. 1(5), 470–488 (2014).

Singh, S. P. Impact of end groups on the performance of non-fullerene acceptors for organic solar cell applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 7(40), 22701–22729 (2019).

Arshad, M. N., Shafiq, I., Khalid, M. & Asiri, A. M. Exploration of the intriguing photovoltaic behavior for fused indacenodithiophene-based A-D-A conjugated systems: A DFT model study. ACS Omega 7(14), 11606–11617 (2022).

Duan, L., Elumalai, N. K., Zhang, Y. & Uddin, A. Progress in non-fullerene acceptor based organic solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 193, 22–65 (2019).

Rasool, F. et al. Heterocyclic donor moiety effect on optical nonlinearity behavior of chrysene-based chromophores with push-pull configuration via the quantum chemical approach. ACS Omega https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c07596 (2024).

Giannini, S. et al. On the role of charge transfer excitations in non-fullerene acceptors for organic photovoltaics. Mater. Today 80, 308–326 (2024).

Lin, Y. et al. An electron acceptor challenging fullerenes for efficient polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 27(7), 1170–1174 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Effect of isomerization on high-performance nonfullerene electron acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140(29), 9140–9147 (2018).

Li, T. et al. Fused tris (thienothiophene)-based electron acceptor with strong near-infrared absorption for high-performance as-cast solar cells. Adv. Mater. 30(10), 1705969 (2018).

Knupfer, M. Exciton binding energies in organic semiconductors. Appl. Phys. A 77, 623–626 (2003).

Cong, P. et al. Asymmetric chlorination of A 2–A 1–D–A 1–A 2 type non-fullerene acceptors for high-voltage organic photovoltaics. Chem. Commun. 58(96), 13373–13376 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Benzotriazole-based asymmetric nonfullerene acceptors with AD-A1-A2 type structure for organic solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 473, 145215 (2023).

Dai, T. et al. Optimizing molecular crystallinity and suppressing electron-phonon coupling in completely non-fused ring electron acceptors for organic solar cells. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202403051 (2024).

Jia, B. et al. Enhancing the performance of a fused-ring electron acceptor by unidirectional extension. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141(48), 19023–19031 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Electronic absorption spectra and third-order nonlinear optical property of dinaphtho [2, 3-b: 2’, 3’-d] Thiophene-5, 7, 12, 13-Tetraone (DNTTRA) and its phenyldiazenyl derivatives: DFT calculations. Comput. Chem. 8(04), 43 (2020).

Kukkonen, E., Lahtinen, E., Myllyperkiö, P., Haukka, M. & Konu, J. Nonlinear optical properties of diaromatic stilbene, butadiene and thiophene derivatives. New J. Chem. 45(15), 6640–6650 (2021).

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B.v Petersson, Ga. Gaussian 09, Revision D. 01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT. See also: http://www.gaussian.com2009.

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Account. 120(1–3), 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x (2008).

Khalid, M. et al. Exploration of noncovalent interactions, chemical reactivity, and nonlinear optical properties of piperidone derivatives: A concise theoretical approach. ACS Omega 5(22), 13236–13249 (2020).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-Class Functionals and 12 other functionals. Theoret. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Paschoal, D., Costa, M. F. & Dos Santos, H. F. NLO-X (X= I-III): New Gaussian basis sets for prediction of linear and nonlinear electric properties. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 114(12), 796–804 (2014).

Dennington, R., Todd, A., Keith, T. A., Millam, J. M. Semichem, Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, GaussView, Version 6. (2016).

Khan, M. U. et al. Theoretical investigation of nonlinear optical behavior for rod and T-shaped phenothiazine based D-π-A organic compounds and their derivatives. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 25(10), 101339 (2021).

Weinhold, F., Glendening, E. D. NBO 5.0 Program Manual: Natural Bond Orbital Analysis Programs, Vol. 53706 (Theoretical Chemistry Institute and Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin, 2001).

Tenderholt, A. L. PyMOlyze, Version 2.0 (2007).

OriginPro, V. OriginLab Corporation. (Northampton, 2016).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33(5), 580–592 (2012).

Zhurko, G. A., Zhurko, D. A. ChemCraft Program Version 1.6 Build 315 (2009).

Gilowski, M. et al. Gauss sum factorization with cold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100(3), 030201 (2008).

Hanwell, M. D. et al. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 4(1), 1–17 (2012).

Chang, S.-L. et al. Isomerically pure benzothiophene-incorporated acceptor: Achieving improved V Oc and J Sc of nonfullerene organic solar cells via end group manipulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11(36), 33179–33187 (2019).

Khalid, M. et al. NLO potential exploration for D–π–A heterocyclic organic compounds by incorporation of various π-linkers and acceptor units. Arab. J. Chem. 14(8), 103295 (2021).

Khalid, M. et al. first principles study of electronic and nonlinear optical properties of A-D–π–A and D–A–D–π–A configured compounds containing novel Quinolone–Carbazole derivatives. RSC Adv. 10(37), 22273–22283 (2020).

Khalid, M. et al. Effect of different end-capped donor moieties on non-fullerenes based non-covalently fused-ring derivatives for achieving high-performance NLO properties. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1395 (2023).

Arif, N. et al. Synthesis, spectroscopic, SC-XRD/DFT and non-linear optical (NLO) properties of chromene derivatives. RSC Adv. 13(1), 464–477 (2023).

Mahmood, A., Abdullah, M. I. & Khan, S.U.-D. Enhancement of nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of indigo through modification of auxiliary donor, donor and acceptor. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 139, 425–430 (2015).

Sun, Y., Yang, Z., Hou, D. & Pan, S. Theoretical investigation on the balance between large band gap and strong SHG response in BMO 4 (M= P and As) crystals. RSC Adv. 7(5), 2804–2809 (2017).

Nan, M. I. et al. Mono-and Di-substituted pyrene-based donor-π-acceptor systems with phenyl and Thienyl π-conjugating bridges. Dyes Pigm. 181, 108527 (2020).

Goszczycki, P., Stadnicka, K., Brela, M. Z., Grolik, J. & Ostrowska, K. Synthesis, crystal structures, and optical properties of the π-π interacting pyrrolo [2, 3-b] quinoxaline derivatives containing 2-thienyl substituent. J. Mol. Struct. 1146, 337–346 (2017).

Costa, M. P., Prates, L. M., Baptista, L., Cruz, M. T. & Ferreira, I. L. Interaction of polyelectrolyte complex between sodium alginate and chitosan dimers with a single glyphosate molecule: A DFT and NBO study. Carbohyd. Polym. 198, 51–60 (2018).

Chattaraj, P. K. & Roy, D. R. Update 1 of: Electrophilicity Index. Chem. Rev. 107(9), PR46–PR74 (2007).

Mazhar, S. et al. Facile synthesis, crystal growth, quantum chemical studies of electronic structure and of the profoundly persuasive NLO organic crystal: Ethyl 4-[N, N-Bis (p-Toluenesulfonyl)]-Aminobenzoate. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 41(1), 122–122 (2019).

Khalid, M. et al. Influence of end-capped modifications in the nonlinear optical amplitude of nonfullerene-based chromophores with a D-π-A architecture: A DFT/TDDFT study. ACS Omega 7(27), 23532–23548 (2022).

Imran, M. et al. Exploration of photophysical and nonlinear properties of salicylaldehyde-based functionalized materials: A facile synthetic and DFT approach. ACS Omega 6(49), 33914–33922 (2021).

Hussain, A. et al. Structural parameters, electronic, linear and nonlinear optical exploration of thiopyrimidine derivatives: A comparison between DFT/TDDFT and experimental study. J. Mol. Struct. 1201, 127183 (2020).

Khan, M. U. et al. First theoretical framework of Superalkali metals [M3X (M=Li, Na, k; X=O, S, F, N)] doped all-boron b38 nanocluster: A promising class of nonlinear optical materials for optoelectronic applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 440, 114667 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Ultraviolet narrowband photomultiplication type organic photodetectors with Fabry-Pérot resonator architecture. Adv. Func. Mater. 32(29), 2203606 (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Efficient semitransparent layer-by-layer organic photovoltaics via optimizing wide bandgap and narrow absorption polymer layer thickness. Solar RRL 6(8), 2200308 (2022).

Rahmalia, W., Fabre, J.-F., Usman, T. & Mouloungui, Z. Aprotic solvents effect on the UV–visible absorption spectra of Bixin. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 131, 455–460 (2014).

Adeoye, M. D. et al. Effect of solvents on the electronic absorption spectra of 9, 14 dibenzo (a, c) phenazine and tribenzo (a, c, i) phenazine. Sci. Res. Essays 4, 107–111 (2009).

Mora-Diez, N., Montero, L. A. & Fabian, J. Molecular orbital modeling of solvent effects on excited states of organic molecules. J. Mol. Struct. (Thoechem) 453(1–3), 49–57 (1998).

Goszczycki, P., Stadnicka, K., Brela, M. Z., Grolik, J. & Ostrowska, K. Crystal structures, and optical properties of the π-π interacting pyrrolo [2, 3-b] quinoxaline derivatives containing 2-thienyl substituent. J. Mol. Struct 1146, 337–346 (2017).

Ans, M. et al. Designing three-dimensional (3D) non-fullerene small molecule acceptors with efficient photovoltaic parameters. ChemistrySelect 3(45), 12797–12804 (2018).

Ans, M., Ayub, K., Bhatti, I. A. & Iqbal, J. Designing indacenodithiophene based non-fullerene acceptors with a donor-acceptor combined bridge for organic solar cells. RSC Adv. 9(7), 3605–3617. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8RA09292C (2019).

Tsutsumi, N., Morishima, M. & Sakai, W. Nonlinear optical (NLO) polymers. 3. NLO polyimide with dipole moments aligned transverse to the imide linkage. Macromolecules 31(22), 7764–7769 (1998).

Mahmood, A., Khan, S.U.-D. & Rana, U. A. theoretical designing of novel heterocyclic azo dyes for dye sensitized solar cells. J. Comput. Electron. 13(4), 1033–1041 (2014).

Lakhera, S., Rana, M. & Dhuliya, V. Enhancement of the electronic and optical properties of superalkali metal adsorbed Al10N10 nanocage. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 185, 108882 (2025).

Lakhera, S. et al. Enhanced nonlinear optical and optical limiting responses of 7-diethylamino-4-methyl Coumarin functionalized with silver nanoparticles: A combined experimental and DFT study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 457, 115910 (2024).

Lakhera, S., Rana, M. & Devlal, K. Comprehensive quantum chemical study of the associative complex of para-aminobenzoic acid and 7-diethylamino 4-methyl coumarin by adsorption and aromatic bridges. J. Mol. Model 30(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-023-05816-w (2024).

Lakhera, S., Devlal, K. & Rana, M. Utilization of methyclothiazide adsorbed with malonamide for quantum chemical applications: A DFT and DFT-D2/D3 studies. Optik 295, 171485 (2023).

Arshad, M. N. et al. Influence of peripheral modification of electron acceptors in nonfullerene (O-IDTBR1)-based derivatives on nonlinear optical response: DFT/TDDFT study. ACS Omega 7(14), 11631–11642 (2022).

Sivaranjani, T., Xavier, S. & Periandy, S. nm R, FT-IR, FT-Raman, UV spectroscopic, HOMO–LUMO and NBO analysis of cumene by quantum computational methods. J. Mol. Struct. 1083, 39–47 (2015).

Khalid, M. et al. Theoretical designing of non-fullerene derived organic heterocyclic compounds with enhanced nonlinear optical amplitude: A DFT based prediction. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 20220 (2022).

Khalid, M. et al. Efficient tuning of small acceptor chromophores with A1-π-A2-π-A1 configuration for high efficacy of organic solar cells via end group manipulation. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 25(8), 101305 (2021).

Kara Zaitri, L. & Mekelleche, S. M. Computational study of linear and nonlinear optical properties of substituted thiophene imino dyes using long-range corrected hybrid DFT methods. Mol. Phys. 118(4), 1618508 (2020).

Alparone, A. Linear and nonlinear optical properties of nucleic acid bases. Chem. Phys. 410, 90–98 (2013).

Plaquet, A. et al. In silico optimization of merocyanine-spiropyran compounds as second-order nonlinear optical molecular switches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10(41), 6223–6232 (2008).

Lipkowitz, K. B. & Boyd, D. B. Three-dimensional structure database searches. Rev. Comput. Chem. 7, 67 (2009).

Muhammad, S. et al. Benchmark study of the linear and nonlinear optical polarizabilities in proto-type NLO molecule of para-nitroaniline. J. Theor. Comput. Chem. 18(06), 1950030 (2019).

Paul, D., Deb, J. & Sarkar, U. A detailed DFT study on electronic structures and nonlinear optical properties of doped C30. ChemistrySelect 5(23), 6987–6999. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202001988 (2020).

Deb, J., Paul, D. & Sarkar, U. Density functional theory investigation of nonlinear optical properties of T-graphene quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. A 124(7), 1312–1320. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.9b10241 (2020).

Zhang, A. et al. A systematic study of the structure-property relationship of a series of nonlinear optical (NLO) Julolidinyl-based chromophores with a Thieno [3, 2-b] thiophene moiety. J. Mater. Chem. C 3(2), 370–381 (2015).

Shafiq, I. et al. A theoretical approach for exploration of non-linear optical amplification of fused azacycle donor based thiophene polymer functionalized chromophores. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27(5), 101707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscs.2023.101707 (2023).

Hussain, S. et al. Efficient synthesis of nicotinaldehyde-based crystalline organic derivatives: Comparative analysis between experimental and DFT study. J. Mol. Struct. 1290, 135948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135948 (2023).

Shafiq, I. et al. Theoretical perspective toward designing of 5-Methylbenzo [1,2-b:3,4-B′:6,5-B″] trithiophene-based nonlinear optical compounds with extended acceptors. ACS Omega 8(42), 39288–39302. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04774 (2023).

Haq, S. et al. Exploring the influence of fused heterocyclic donor moieties on optical nonlinearity of styrylthiophene based chromophores: A DFT study. Comput. Theoretic. Chem. 1240, 114788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2024.114788 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Muhammad Khalid gratefully acknowledges the financial support of HEC Pakistan (Project No. 20-14703/NRPU/R&D/HEC/2021). Authors are thankful for cooperation and collaboration of A.A.C.B from IQ-USP, Brazil especially for his continuous support and providing computational lab facilities. A.A.C.B. (grant 2015/01491-3) is highly thankful to Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo for the cooperation and financial assistance. The authors thank the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R253), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. K.C. acknowledges the support from the doctoral research fund of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saadia Haq: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing Original Draft; Visualization Muhammad Khalid: Supervision; Investigation; Resources; software; project administration; Methodology; Validation. Ataualpa Albert Carmo Braga: Conceptualization; Visualization; Resources; software; project administration; Methodology; Norah Alhokbany: Data Curation; Writing—review & Editing; Formal analysis, Funding acquisition Ke Chen: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing—review & Editing; Funding acquisition; Visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haq, S., Khalid, M., Braga, A.A.C. et al. Design and evaluation of indacenothienothiophene based functional materials for second and third order nonlinear optics properties via DFT approach. Sci Rep 15, 13262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96902-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96902-x