Abstract

The aging population worldwide is on the rise, leading to a higher number of Parkinson’s disease (PD) cases each year. PD is presently the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease, affecting an estimated 7–10 million individuals globally. This research aimed to identify mobile genetic elements in human fecal samples using a shotgun metagenomics approach. We identified over 44,000 plasmid contigs and compared plasmid populations between PD patients (n = 68) and controls (n = 68). Significant associations emerged between groups (control vs PD) based on plasmid alpha and beta diversity. Moreover, the gene populations present on plasmids displayed marked differences in alpha and beta diversity between PD patients and controls. We identified a considerable number of phage contigs that were differentially abundant in the two groups. We also developed a predictive machine learning model based on phage abundance data, achieving a mean Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.74 with a standard deviation of 0.105 and a mean F1 score of 0.68 with a standard deviation of 0.14 across cross-validation folds, indicating moderate discriminatory power. Additionally, when tested on external data, the model yielded an AUC of 0.74 and an F1 score of 0.8, further demonstrating the predictive potential of phage populations in Parkinson’s disease. Further, we improved the continuity and identification of the protein coding regions of the phage contigs by implementing alternative genetic codes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder globally, affecting 7–10 million individuals1. Although the underlying causes of PD remain unclear, it is widely acknowledged that the composition of the gut microbiota (GM) can affect brain health and is linked to PD2.

Non-motor symptoms typically manifest before the onset of characteristic motor symptoms in PD patients. One of the most prevalent non-motor symptoms is gastrointestinal dysfunction, which is frequently associated with alpha-synuclein accumulation in the enteric nervous system3,4,5,6. The documented accumulation of alpha-synuclein in the enteric nervous system, followed by its progression to the central nervous system, supports the potential role of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in PD7,8.

The microbiota-gut-brain axis is a two-way communication pathway linking the GM and the central nervous system. This pathway plays a role in neural development, neuroinflammation, and modulation of complex behaviors9,10. A growing body of evidence suggests that the GM may have a direct or indirect impact on central processes by activating the immune system (e.g. through inflammatory cytokines and chemokines)11 and producing neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and glutamate), short-chain fatty acids12, and important dietary amino acids such as tryptophan and its metabolites13. Conversely, the brain can influence gut peristalsis and sensory and secretion function primarily through the vagus nerve14.

Previous publications that used the Helsinki cohort have previously reported several findings regarding the relationship between GM and PD2,6,12,15,16,17,18,19. These include a decrease in the abundance of Prevotellaceae in the GM of PD patients, a positive correlation between the relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and the severity of certain PD motor symptoms, a persistence of these GM changes after a 2-year period, and a connection between GM and the progression of PD2,15. The current study augments these foundational insights by using shotgun metagenomic sequencing to the Helsinki cohort to interrogate the microbiome at a higher resolution. Specifically, we focus on the characterization of mobile genetic elements (MGEs), which may play a pivotal role in microbial community dynamics and the progression of PD.

GM comprises the mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids and phages, which remain mostly undetermined with regard to PD. Plasmids are commonly found in bacteria and can carry a variety of genetic material, including genes related to antibiotic resistance. Phages are highly variable and are engaged in an ongoing battle with bacteria, thus affecting microbiota composition. Investigating the phage populations that may impact GM composition is important for understanding the gut microbiome and its relationship to health20,21,22,23. The human virome has been linked to several illnesses, such as cancer24, type 2 diabetes25, and preschool asthma26, Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)27, and also to IBD-associated immunomodulation28. Interestingly, viral transfer to the gut has been tested as a treatment in a model system29. Thus, research of MGEs is crucial in the context of gut microbiome and health, especially in the case of PD.

The large diversity of gut phages, with their wide range of sizes and genetic codes, makes studying the entire gut phage population a challenge. Unlike bacterial communities, where we can use common primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene, there’s no single genetic marker that works for all gut phages. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to develop universal detection methods. However, resources like the Gut Phage Database (GPD)30 provide a valuable solution. GPD is a large collection containing around 143,000 non-redundant viral genomes from over 28,000 metagenomes, serving as a standardized reference point for gut related research. In our study, we utilized the GPD as a reference database for our gut phage abundance analysis and gut phage population diversity analysis.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) loci in bacterial genomes serve as a defense against mobile genetic elements (MGEs). These loci, composed of direct repeats (DRs) and spacers, allow the CRISPR-associated (Cas) system to target invading phages31. Interestingly, certain phages themselves carry CRISPR genes within their genomes, which can target other MGEs or even host genes. Furthermore, phages lacking cas genes have been reported to possess mini-CRISPR arrays32,33, underscoring the complexity and potential versatility of CRISPR systems within phage populations.

Emerging evidence suggests that some phages may utilize alternative genetic codes, where a standard stop codon is reassigned to encode an amino acid instead of signaling the end of translation. This recoding of stop codons can significantly impact how phage genes are expressed and regulated34,35. Given the prevalence of phages in the human gut, it is intriguing to investigate whether these alternative coding strategies are present in gut phages. In this study, we explored the potential different codon usage among gut phages.

Previous research using shotgun metagenomic sequencing has provided insights into the gut microbiome’s role in Parkinson’s disease (PD)36,37,38. In our study, we also utilized shotgun metagenomic sequencing, focusing specifically on the fecal phage and plasmid populations. We compared these populations between PD patients and control subjects, hypothesizing a significant difference that could influence the gut microbiota composition.

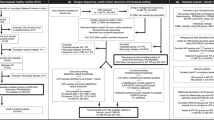

Methods

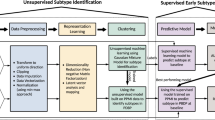

An overview of the analysis pipeline is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Study populations

This case–control study compared 68 patients with a diagnosis of PD according to the Queen Square Brain Bank criteria with 68 sex- and age-matched control subjects39 (Table 1). Exclusion criteria covered a broad range of conditions and medications that could independently affect the fecal microbiome 2. To ensure ethical conduct, the research was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa, following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants agreed to participate by providing written informed consent.

Stool sampling

Stool samples were collected at home by all PD patients and controls included in the Helsinki cohort2,15 using DNA Stool Collection Tubes containing DNA Stabilizer from the PSP (Pre-analytical Sample Processing) Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit (STRATEC Molecular, (Stratec, Birkenfeld, Germany)), and were subsequently frozen and stored at − 80 °C. Stool samples were shipped on dry ice to the DNA Sequencing and Genomics Laboratory at the Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Finland for DNA extraction, sequencing and data analysis.

DNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing

DNA extraction of the samples was performed using the STRATEC Molecular PSP Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit compatible with the DNA Stool Collection Tubes with DNA Stabilizer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were randomized between extraction batches to minimize batch effects.

After total DNA extraction, DNA libraries were prepared using the Nextera Library Preparation Biochemistry (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Shotgun sequencing for all samples was performed with the Illumina platforms Nextseq 500 (170 bp + 140 bp) and NovaSeq 6000 (150 bp + 150 bp).

Sequencing analysis

Cutadapt (v.1.8.1)40 was used to trim adapter and long G stretch sequences from 3’ end of the reads (using -a option), 5 bps were trimmed from 5’ end of the reads ( -U 5 option), minimum quality value was set to 20 (-q 20 option) and minimum read length was set to 50bps (-m 50 option). Used sequences for trimming R1: AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCAC & GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG and R2:

AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGTAGGGAAAGAGTGTAGATCTCGGTGGTCGCCGTATCATT & GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG. Trimmed reads were mapped against human reference sequence (GRCh38.p11) using BWA mem v.0.7.12-r103941 and unmapped reads were assembled independently, sample by sample, using SPAdes (v3.11.1)42 with meta option.

De novo plasmid identification from assemblies

Reconstruction of plasmids from the metagenomic assemblies was performed using the PlasX tool43. For each sample assembly, genes were called using Anvio44, with “anvi-export-gene-calls –gene-caller prodigal”. Then, genes were annotated using PlasX de novo gene family database with “plasx search_de_novo_families” command. Further, Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) and Pfam annotation was done using Anvio with “anvi-run-ncbi-cog” and “anvi-run-pfams” commands. COG14 and Pfam_v32 databases were used since PlasX models are compatible with only these databases. Then, “plasx predict” from PlasX was used to identify plasmid contigs from the assemblies. The threshold of 0.5 plasx score was used for the selection. The metagenomic reads were then mapped back to predicted plasmid contigs using Bowtie2 v2.4.445. If there were more than nine reads mapped with outward oriented pairs, we assumed that the contig is circular. MobMess43 was used to identify plasmid systems and classify the type of the plasmid (backbone, fragment, compound). The clustering of the plasmid sequences was done using MMseqs2 v92deb9246 with default settings to get the final non-redundant list. To assess plasmid prevalence, a presence-absence matrix was constructed based on the clustering results, where '1' indicated the presence of a cluster in a sample and '0' indicated absence.

Gene and taxonomic annotation of plasmid contigs

We checked the antimicrobial resistance genes within the plasmid contigs. First genes were annotated using Prokka47. To use the same version as our Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) study (Duru et al., in preparation), we used the following version of deepARG48 downloaded from the project git repository (git commit “ab05670”; https://bitbucket.org/gusphdproj/deeparg-ss/src/ab0567032235b4c67a36a0bc27d80fc2dd4f7eda/). Then, deepARG was run with default settings using plasmid contig genes. To predict the COG groups of the plasmid genes, we ran reCOGnizer49.

We predicted the taxonomy of the plasmid contigs using Kaiju v1.8.250. NCBI RefSeq plasmid database (April 2022) was used to build the Kaiju database using “kaiju-makedb -s plasmids”. Plasmid contigs were then annotated using Kaiju with options “-a mem -m 14 -s 80”.

De novo identification of viral contigs and gene annotation

To identify viral contigs from metagenomic assemblies, we used VIBRANT v1.2.151 with default settings. Additional quality assessment was performed with CheckV v1.0.152 and the CheckV database v1.5. Viral contig lengths were refined using CheckV to eliminate host contamination. The taxonomic annotation of the identified contigs was done using Kaiju v1.8.250 with “-a mem -m 14 -s 80” settings and Kaiju “viruses” database (downloaded on March 2022). Identification of CRISPR-Cas systems in the viral contigs was performed using CRISPRCasTyper v1.8.053 with options “—minNR 2—prodigal meta”. We used SpacePHARER v5-c2e680a54 to identify targets of the spacers.

Identification of crAss-like phages

To specifically identify crAss-like phages from our viral contigs, we performed the same methods as described in Guerin et al.55. The proteome of the viral contigs was aligned against conserved crAss-like phage proteins; UGP_018 and UGP_092 (crAss polymerase, and crAss terminase, respectively). The alignment was done using BLAST v2.12.056 with e-value threshold 1E-05. If there was a blast hit with query alignment length ≥ 350 bp, we selected them as putative crAss-like phages. We further filtered the results by selecting only contigs larger than 70kbp. We utilized the anvi’o v8 platform44 to construct a pan-genome from crAss-like phages. During the pan-genome construction, we used the settings –ultra-sensitive, –minbit 0.0, and –mcl-inflation 1.2 in anvi’o. Subsequently, we extracted gene clusters using the “anvi-get-sequences-for-gene-clusters” command. The presence and absence of gene clusters among the crAss-like phages were then transformed into a binary count matrix, which was used to calculate the percentage of shared orthologous proteins. To identify potential families of crAss-like phages, we clustered the percentage of shared proteins matrix using the Ward variance minimization algorithm. Finally, we visualized the results in a heatmap, generated using the code available at.

https://github.com/icemduru/Parkinson_Disease_Gut_Microbiota_Phage_Plasmid_Diversity_ML/tree/main/Data_Visualizations. We also examined whether there were gene clusters specific to control or PD crAss-like phages by performing a Fisher’s exact test.

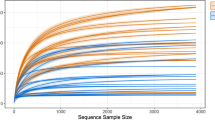

Phage population analysis using GPD

To complement our de novo phage identification, which was focused on identification of the phages present in our study population and their contig sequences, we used a secondary approach by aligning our metagenomic reads to the GPD (last modified on 2021-05-29, downloaded in August 2022)30. The GPD contains 142,809 phage genomes ranging in size from 10,000 to 419,037 nucleotides, with an average genome length of 37,586.3 nucleotides. We aligned our shotgun sequencing reads against the GPD, using Bowtie2 v2-2.3.4.345 with default options. The alignment files were then sorted using Samtools v1.1257. Raw count data was derived from the sorted alignment files by counting the single unique reads that aligned to each phage genome in the GPD. Relative abundance was calculated as the ratio of a phage genome’s count to the total number of reads.

Differential abundance analyses on GPD count data

Differential abundance analyses were done with DESeq2 v1.44.058. Initially, the GPD count data were filtered to include only those phages that met both of the following criteria: (1) a total read count of at least 30 across all samples, and (2) a read count of at least 1 in a minimum of 15 samples. For the DESeq2 output, we used apeglm for log2 fold change shrinkage59. Final filtering was applied using the criteria of padj < 0.05 and |log2 fold change|> 0.25.

Statistical analysis

For alpha diversity analysis, we utilized non-rarefied data across all datasets and calculated five alpha diversity indices: observed richness, Chao1, ACE, Shannon index, and Inverse Simpson index. Statistical comparisons between variables were conducted with the phyloseq R package60 using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for categorical variables (PD status and gender) and Spearman’s rank correlation test for continuous variables (age and BMI).

For beta diversity analysis, we applied different approaches based on the data type. For count data, including GPD count data, plasmid gene occurrence using COG annotation, and plasmid antibiotic resistance genes occurrence, we first performed centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation on the data, followed by the calculation of Euclidean distance between CLR-transformed samples (Aitchison Distance). For binary data, such as plasmid population, we did not perform CLR transformation. Instead, we directly calculated the Jaccard distance between the samples using the binary = TRUE option. Statistical differences in community composition were assessed using adonis2 (PERMANOVA) from the vegan package61. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was performed on the transformed data, and ordination plots were visualized using the plot_ordination function from the phyloseq package. The analysis code can be found: https://github.com/icemduru/Parkinson_Disease_Gut_Microbiota_Phage_Plasmid_Diversity_ML/tree/main/Alpha_Beta_diversity

Genetic code diversity and coding density calculation in phages

We predicted genes of the phages using prodigal with three different runs using “-g 4”, “-g 11”, and “-g 15” to get gene prediction with genetic codes of 4, 11, and 15 respectively. The predicted genes were then used to calculate coding density. The coding density was calculated with the same method as Borges et al.35. using “get_CD.py” python code from.

https://github.com/borgesadair1/AC_phage_analysis (downloaded August 2022).

Machine learning model

We studied whether phages or plasmids could be used to predict the classification of samples into PD or the control group utilizing a random forest machine learning approach using Scikit-learn python package62.

For phages, the relative abundance of all phages within the GPD was used as input features for the model. We initialized a RandomForestClassifier with a maximum depth of 5, 100 estimators, and a minimum samples split of 10. We used StratifiedKFold for fivefold cross-validation to maintain the proportion of classes in each fold. During each fold, we trained the classifier on the training set and evaluated it on the test set. We calculated various performance metrics, including the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), F1 score, recall, precision, and accuracy for each fold. We also plotted the ROC curves for each fold and calculated the mean ROC curve with variability. To identify the most important features, we calculated the feature importances from the Random Forest model. We also wanted to use publicly available data to evaluate our model’s performance on unseen data. We downloaded metagenomics sequences of 20 random samples (10 PD sample, 10 control sample) from a gut Parkinson’s shotgun metagenomics study 37 (ENA project PRJNA834801). Relative abundance for those samples was determined by aligning the data to the GPD and then dividing the read count of each phage genome by the total number of reads. We then used the relative abundance to predict their condition (PD or control).

For plasmids, we used our de novo identified plasmids, and their presence-absence matrix that was constructed based on the clustering results. We used the same methods as we used RandomForestClassifier in phages. The codes used for machine learning models can be seen in our github repository (https://github.com/icemduru/Parkinson_Disease_Gut_Microbiota_Phage_Plasmid_Diversity_ML/tree/main/Machine_Learning_Model).

Results

Plasmid identification from assemblies

PlasX plasmid prediction analysis revealed a total of 44,409 plasmid contigs across 136 samples. Control samples harbored a higher number of plasmid contigs (24,559) compared to PD samples (19,850). The average number of contigs per sample was 361 (ranging from 139 to 649) in the control group and 292 (ranging from 155 to 662) in the PD group. The average length of plasmid contigs was 4,065 bp, with a range of 1,000 bp to 275,216 bp. We clustered the 44,409 plasmid sequences based on their sequences and obtained 29,096 clusters (Supplementary Tables S1, S2), representing our non-redundant list of plasmid contigs. We also identified plasmid systems using the MobMess tool and identified 2,308 backbone plasmids and 760 as compound plasmids (Supplementary Tables S3, S4).

To determine taxonomic annotation of all plasmid contigs, the NCBI RefSeq plasmid database (April 2022) was used. Enterococcus and Vescimonas plasmids were the most commonly observed on the genus level (Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Plasmid population comparison between groups

We compared plasmid populations between PD and control group, gender, BMI, and age using the presence-absence matrix that was constructed based on the clustering results. Significant alpha diversity differences were identified between PD patients and control subjects using pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum test for observed plasmid richness index (Control: 357.59 ± 125.97, PD: 289.72 ± 90.15, p = 0.0007085), Inverse Simpson index (Control: 353.77 ± 123.93, PD: 287.35 ± 89.08, p = 0.0008043), and Shannon index (Control: 5.81 ± 0.37, PD: 5.62 ± 0.29, p = 0.0007551). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S6). No significant differences or associations were observed for the other variables. Additionally, significant beta diversity differences were found between PD patients and controls (p-value = 0.0003), while no significant differences were detected for the other variables (Supplementary Table S6).

Alpha and beta Diversity analysis of control vs. Parkinson groups for plasmid population. (a) Alpha diversity comparison between control and Parkinson groups using five different richness indices: Observed Richness, Chao1, ACE, Shannon Index, and Inverse Simpson Index. Plasmid richness values are represented by box plots, where each dot corresponds to an individual sample. The p-values for group comparisons were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and are displayed above each box plot. (b) Beta diversity analysis visualized using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on the group variable (control vs. Parkinson). Red dots represent samples from the control group, while blue dots represent samples from the Parkinson group. The p-value and R2 value were determined using PERMANOVA and are shown on the right side of the PCoA plot. A star (*) is used next to the p-value if it is lower than 0.05, indicating statistical significance.

In addition to diversity, we also checked the percentage abundance of the plasmids in each sample. The percentage abundance of plasmids did not show any significant difference between PD and control groups (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Gene annotation of plasmid contigs

To gain general insight into plasmid gene functions, Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) categories and COG functions of plasmid genes were annotated. The most common COG categories were “Replication, recombination and repair”, “Cell cycle control, cell division, and chromosome partitioning”, and “Transcription”. The most common COG functions were “ParA-like ATPase”, “Site-specific DNA recombinase SpoIVCA/DNA invertase PinE”, and “Chromosome segregation ATPase Smc” (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S7).

We also specifically identified antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) within the plasmid genes. In every sample, at least one ARG was found within the plasmid genes, with vancomycin resistance gene, vanS, being the most frequently observed gene in this category (Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Table S8). Additionally, the predominant class of antibiotic resistance genes present on plasmids in the gut microbiota of both PD and control groups was the glycopeptide antibiotic class (Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Table S8).

Plasmid gene comparison between groups

We examined the gene populations carried by plasmids using COG function annotation occurrence by sample. Alpha diversity analysis revealed significant differences between the PD and control groups, as indicated by the observed plasmid gene richness index (Control: 186.31 ± 56.90, PD: 162.32 ± 38.41, p = 0.02905), Chao1 index (Control: 321.84 ± 99.23, PD: 273.69 ± 67.32, p = 0.008623), and ACE index (Control: 374.79 ± 118.27, PD: 319.69 ± 77.78, p = 0.01181) (Supplementary Fig. S6, Supplementary Table S6). Beta diversity analysis further supported these differences, with a PERMANOVA test yielding a p-value of 0.007599. Additionally, significant differences in plasmid gene diversity were observed between genders, as shown by the observed plasmid gene richness (Female: 167.28 ± 51.63, Male: 181.35 ± 47.32, p = 0.04036) and ACE (Female: 329.93 ± 102.28, Male: 364.54 ± 102.51, p = 0.0489) indices in the alpha diversity analysis (Supplementary Fig. S6, Supplementary Table S6). For other variables, we did not observe statistical significance in alpha or beta diversity analyses.

In addition, we compared ARGs gene counts between groups. No differences were observed between PD and controls, sex, BMI, or age for alpha diversity or for beta diversity regarding ARGs (Supplementary Fig S6, Supplementary Table S6).

Predictive machine learning model for plasmid populations

The random forest classifier, using our de novo identified plasmids and their presence-absence matrix as data, was evaluated through fivefold cross-validation. The model achieved a mean AUC of 0.661 (± 0.105), indicating moderate discriminative power. The mean F1 score was 0.655 (± 0.096), with a recall of 0.781 (± 0.155) and a precision of 0.576 (± 0.103), suggesting the model is better at identifying positives but at the cost of more false positives. The accuracy was 0.588 (± 0.123) (Fig. 2).

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the random forest classifier trained on de novo identified plasmid presence-absence data. The model was evaluated using fivefold cross-validation. The solid blue line represents the mean ROC curve across all folds, and the shaded area indicates ± 1 standard deviation. The individual ROC curves for each fold are shown in lighter colors, with their corresponding AUC values indicated.

De novo identification of viral contigs from metagenomic assembly

Using Vibrant, we were able to detect 111,099 viral contigs from the entire dataset. Among these, 61,793 were from control samples and 49,306 from PD samples (Supplementary Table S9). Although most of the contigs were low quality draft, some complete circular quality contigs were also observed (Supplementary Fig. S7). The Vibrant classification revealed that the number of lytic type viral contigs was higher than lysogenic type in the gut microbiota (Supplementary Fig. S7). Additionally, we found that lysogenic type contigs tended to be longer than lytic type contigs. At the order level, Caudovirales was the most dominant order (Supplementary Table S10). At the family level, the most prevalent taxa were Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae, respectively.

Identification of CRISPR-Cas systems in viral contigs

In our study, we focused on examining CRISPR-Cas systems within the identified viral contigs. Our analysis revealed that out of the 111,099 viral contigs examined, 144 contained cas genes; type II-D was the most frequently observed cas gene type. Overall, 163 cas genes were detected across the 144 viral contigs, with the majority (n = 136, 84%) belonging to the II-D type. Other Cas gene types that were detected in the identified viral contigs included IV-B, V-F1, VI-D, I-C, VI-A, V-A, VI-B1, I-E, II-B, and I-B (Supplementary Table S11). Of the 144 viral contigs in which a cas gene was detected, 47 (33%) were identified within a metagenome-assembled genome that was constructed in our previous study63. Notably, our observations revealed that among the cas genes we identified within viral contigs, only 20 had proximate CRISPR arrays, while for the majority (n = 124), no nearby CRISPR arrays were detected. The chi-square statistical analysis of the distribution of CRISPR-Cas systems between Control and PD samples did not reveal any significant overall differences. However, we observed some Cas types that were specifically present in either control or PD samples, albeit in very low frequencies. For instance, the I-C and VI-B1 subtypes were only detected in control samples (n = 2 and n = 1, respectively), while the I-B and II-B subtypes were uniquely observed in PD samples (both n = 1).

Our analysis unveiled the presence of CRISPR arrays lacking cas genes within viral contigs. A total of 1621 CRISPR arrays were detected within the viral contigs, distributed across 1529 distinct viral contigs. Only 20 of them contained a cas gene. It is noteworthy that a majority of these CRISPR arrays consist of less than three repeats (Supplementary Table S11). We also analyzed whether the spacers target any known phages and observed that targets of the spacers were mainly Faecalibacterium and Escherichia phages (Supplementary Table S11).

CrAss-like phages

A more detailed search was conducted for crAss-like phages, which are the most prevalent phages found in the human gut metagenome64 of the identified viral contigs. A total of 118 crAss-like phages were identified, with 92 containing both crAss polymerase and crAss terminase, 11 containing only crAss polymerase, and 15 containing only crAss terminase. A pan-genome analysis of 118 predicted crAss-like phage genomes identified distinct gene clusters. Orthologous protein sharing clustering revealed four main clusters (Fig. 3), suggesting four families (alpha, beta, delta, gamma) of crAss-like phages. These families were validated by comparison to previously published crAss-like phage sequences55. A Fisher’s exact test did not identify any gene clusters specific to control or PD crAss-like phages.

Clustering of crAss-like phages based on shared orthologous proteins. A heatmap representing the percentage of shared orthologous proteins between individual crAss-like phages. Each row and column corresponds to a distinct crAss-like phage. The color intensity of each cell indicates the level of protein sharing between the respective phages. The dendrograms at the top and left sides of the heatmap show hierarchical clustering based on the Ward variance minimization algorithm, grouping phages into four main clusters (alpha, beta, delta, gamma). The color bar at the top differentiates between crAss-like phages isolated from control and Parkinson’s disease patients.

Alpha and beta diversity of phages using GPD read count data

In our downstream analysis, we utilized the GPD as a reference phage database. GPD includes an extensive collection of characterized gut phage genomes that serves as a valuable resource for generalized comparison. Our comparison analysis indicates the alpha diversity of phages was lower in the PD population than in controls as indicated by the observed phage richness index (Control: 24,256.04 ± 4654.45, PD: 21,322.56 ± 3364.16; p = 0.00002137), Chao1 index (Control: 25,189.65 ± 4825.82, PD: 22,177.01 ± 3492.21; p = 0.00003201), and ACE index (Control: 25,916.59 ± 4898.93, PD: 22,842.09 ± 3544.44; p = 0.00003141) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S6). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests revealed significantly lower microbial richness in women compared to men, as supported by Chao1 (Female: 22,887.30 ± 4388.91, Male: 24,479.36 ± 4420.53, p = 0.04991) and Shannon (Female: 7.73 ± 0.36, Male:7.85 ± 0.30, p = 0.03573) indices (Supplementary Fig S6, Supplementary Table S6). No significant associations of alpha diversity were found for age and BMI.

Alpha and beta Diversity analysis of control vs. Parkinson groups for phage population using GPD read count data. (a) Alpha diversity comparison between control and Parkinson groups using five different richness indices: Observed Richness, Chao1, ACE, Shannon Index, and Inverse Simpson Index. Phage richness values are represented by box plots, where each dot corresponds to an individual sample. The p-values for group comparisons were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and are displayed above each box plot. (b) Beta diversity analysis visualized using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on the group variable (control vs. Parkinson). Red dots represent samples from the control group, while blue dots represent samples from the Parkinson group. The p-value and R2 value were determined using PERMANOVA and are shown on the right side of the PCoA plot. A star (*) is used next to the p-value if it is lower than 0.05, indicating statistical significance.

Beta diversity analysis, as measured by PERMANOVA, revealed significant differences in community composition between control and PD samples (p = 0.0002, R2 = 0.01284). We found no statistically significant differences in beta diversity for the remaining variables.

Differential abundance analysis of phages using GPD read count data

Using the DESeq2 tool, we analyzed GPD read count data to compare phage abundance between PD patients and controls. This analysis identified a total of 1,866 differentially abundant phages (Supplementary Table S12). Among these, 824 phages were significantly more abundant in PD patients, while 1,042 were more abundant in the control group.

We further investigated the taxonomy of these differentially abundant phages using GPD metadata. Although the vast majority (approximately 95%) of these phages had undetermined taxonomy, among the small subset that could be classified, the predominant families were Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae. Phages from these families were found to be more abundant in both PD patients and controls. Notably, phages from the families Microviridae and Tectiviridae were specifically more abundant in PD patients, whereas phages belonging to the Gokushovirinae subfamily were more abundant only in the control group.

We also examined the host bacteria of these differentially abundant phages using GPD metadata. The top five genera serving as hosts for the significantly abundant phages were Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, Blautia, and Bifidobacterium. Notably, phages with hosts in the genera Bifidobacterium and Ruthenibacterium were specifically more abundant in PD patients. Specifically, 41 different phages were associated with Bifidobacterium, and 26 phages were associated with Ruthenibacterium as hosts, all of which were more abundant in the PD group.

Predictive machine learning model for phage population

A machine learning approach was used to investigate whether the relative abundance of selected phages could be used to predict sample classification into either PD or control groups. The random forest classifier, using GPD and their read count data (relative abundance) as data, was evaluated through fivefold cross-validation. The classifier’s performance metrics were assessed through several key indicators, AUC, F1 score, recall, precision, and accuracy. The mean AUC across the cross-validation folds was 0.746, with a standard deviation of 0.105, indicating moderate discriminatory power with some variability between folds (Fig. 5). The F1 score, which balances precision and recall, had a mean value of 0.683 and a standard deviation of 0.144, reflecting a reasonable balance between precision and recall, though the higher standard deviation suggests variability in performance across the folds. The recall had a mean of 0.692 with a standard deviation of 0.187. Precision showed a mean of 0.680 and a standard deviation of 0.105. The mean accuracy was 0.691 with a standard deviation of 0.128.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the Random Forest classifier trained on GPD read count data. (a) The model was evaluated using fivefold cross-validation. The solid blue line represents the mean ROC curve across all folds, and the shaded area indicates ± 1 standard deviation. The individual ROC curves for each fold are shown in lighter colors, with their corresponding AUC values indicated. (b) The model’s performance was evaluated on unseen data (external data were downloaded from the ENA database, project PRJNA834801) by using 20 random samples. The figure shows ROC curve performance of the model using 20 random unseen samples (external samples) obtained from a separate gut metagenomic study.

We further evaluated our model’s performance on unseen data (external data) by using 20 random samples from a separate gut metagenomic study (ENA project PRJNA834801). After calculating the relative abundance of GPD phages, we used this data to predict the condition (control vs. PD). The model performed well, achieving a recall of 0.8, precision of 0.8, accuracy of 0.8, F1 score of 0.8, and an AUC 0.74.

Additionally, we tested the model using only the top 50 phages based on feature importance. However, this approach yielded a lower AUC of 0.63 on the unseen data (external data), indicating that utilizing the entire GPD dataset is more effective than focusing on a subset of phages. The AUC of 0.74 supports the potential of GPD relative abundance as a reliable predictive model (Fig. 5).

Genetic code diversity in phages

Recently, it has been shown that phages can adapt to use alternative genetic codes (other than standard code (code 11)) to increase their adaptability35 by recoding the stop codon to prevent premature production of late stage proteins. We tested the coding density of phages using standard code, code 4, and code 15, which are the three codes known to provide a re-coded stop-codon. Of the 142,809 GPD phages, 139,316 (97.5%) phage genomes were predicted to be using standard code, 2,872 (2.01%) using code 15, and 621 (0.43%) to be using code 4 (Supplementary Table S13). Phages predicted to use code 4 exhibited an average coding density of 90% with code 4, but only 70% when analyzed with the standard code. Similarly, phages predicted to use code 15 showed an average coding density of 91% with code 15, compared to just 63% with the standard code. This indicates that, for some phages, structural gene annotation can be significantly improved by using a different genetic code during the annotation process.

In our analysis of the 1,866 differentially abundant GPD phages between the control and PD groups, we found that the majority were predicted to utilize the standard genetic code. Notably, four phages that were significantly more abundant in the PD group were predicted to use genetic code 15. In contrast, no phages in the control group were predicted to use code 15. This suggests that phages utilizing code 15 may be more prevalent in the PD group.

We also checked the coding density of phage contigs that were de novo identified using Vibrant. Of all 111,099 phage contigs, 107,270 (96.5%) were predicted to be using standard code, 996 (0.89%) code 15, and 2,830 (2.54%) code 4 (Supplementary Table S13). Unlike for GPD phages, code 4 was the second most common genetic code preference in our de novo identified phage contigs.

Discussion

Viruses and phages constitute one of the most diverse and extensive groups of biological entities, along with other MGEs like plasmids. They provide an adaptable mechanism for horizontal gene transfer, enabling the movement of genetic material even between distantly related organisms. Viruses and phages have a significant impact on bacterial and archaeal communities, either by terminating them or by enhancing their fitness through the introduction of new genes into their genomes or the genomes of their hosts. Previous research has established an association between PD and gut microbiota (GM) composition at the family, genus and species level, which has been linked to specific metabolite production2,37,65. Therefore, it is important to investigate the nature of these associations and possible causes for GM alterations in PD patients. MGEs have the potential to alter the gut microbiota, and studying them could help us understand the community dynamics and develop new approaches to control the gut environment. As a result, the focus of gut microbiota research has started to shift towards taking MGEs into account.

A previous study reported no significant difference in the abundance of prophages and plasmids between PD and control samples, but the total viral abundance was decreased in the PD group36. However, another study noted a significant difference in prophage and plasmid populations between PD and control groups based on Shannon and Chao1 indices, and total prophage abundance was found to be higher in the PD group than in the control group66. Therefore, further investigations are required to understand the relationship between the MGE population in the gut and PD. In this study, we examined the differences in MGE populations between PD patients and control subjects.

We investigated two types of MGEs, namely plasmids and phages, which have been shown to play a crucial role in regulating the bacterial population of GM and facilitating horizontal gene transfer among bacteria67,68. The occurrence of horizontal gene transfer between phylogenetically distant bacterial groups highlights the importance of the ecological environment as a driving factor for gene exchange69,70. Our findings revealed differences in the community of these mobile elements in PD and control groups. Notably, the variation in GM composition is known to be influenced by various factors, such as BMI25,71, which can impact MGEs. To account for possible confounders, including sex, age, and BMI, we adjusted our statistical models, but residual confounding cannot be entirely excluded.

Plasmid populations and plasmid encoding elements reflect the association and co-evolution of hosts and bacteria. Plasmid populations have been investigated at both their diversity and presence of genes. In this study, we were interested in the plasmid composition of the GM and the genes carried by plasmids. Our analysis revealed differences in alpha and beta diversity of plasmids between PD patients and controls, which is in agreement with an earlier study66 that found significant beta diversity differences for plasmids between these two groups. However, there was no significant difference in the percentual abundance of plasmids observed between the PD and control groups, consistent with the previous findings66. We were also interested in assessing whether the plasmid population could have predictive potential for PD. The machine learning model built using plasmid population data achieved an AUC score of 0.661 (± 0.105). This AUC value indicates that the model has a moderate ability to distinguish between PD patients and controls, suggesting it can differentiate these groups better than random chance, though with limited accuracy.

Plasmids carry genes involved in host-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions, such as virulence genes and ARGs, which can impact the GM population68. Our results indicate that the plasmid gene composition differs between PD patients and controls, as demonstrated by the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Observed plasmid gene richness p = 2.91E-02) and beta diversity (p = 7.60E-03). In addition to general functional annotations, we identified ARGs within the plasmid genes, with the vanS gene being the most prevalent. This gene plays a crucial role in vancomycin-induced resistance, a member of the glycopeptide class of antibiotics72. Vancomycin has been shown to substantially decrease gut microbiota diversity73. The high frequency of the vanS gene on plasmids in the gut environment may reflect an adaptation process by gut bacteria to vancomycin resistance. However, our analysis of plasmid-borne ARGs did not reveal any significant difference in diversity between PD and control groups.

Phages are highly variable and can differ substantially between individuals, similar to bacteria. We analyzed phage communities in both PD and control groups using two complementary approaches. The first approach involved the de novo identification of phage contigs within our assemblies. This method is particularly valuable for characterizing and publishing phage genomes specific to this cohort, enabling in-depth investigation of cohort-specific genomes and genes. The second approach involved aligning reads to the GPD. Leveraging GPD, a comprehensive and generalized database, allowed us to contextualize our findings within a broader framework, thereby facilitating the generalization of our results. The de novo prediction of viral contigs within the metagenomic assemblies led to the discovery of 111,099 viral contigs. Upon identification, it was observed that lytic type viral contigs were more common than lysogenic type viral contigs in the gut microbiota of our samples. Previously, a gut virome study using PacBio sequencing74 reported similar findings, where lytic phages dominated the virome. Interestingly, their study74 also linked phage lifecycle to methylation, with virulent phages showing higher methylation than temperate phages74. In our earlier study, we found that about 28% of the predicted viral sequences are actually part of microbial genomes63. Possibly, the high number of lytic viruses might explain why there were relatively few phages within the microbial genomes. Taxonomic annotation of the predicted viral contigs indicated that Caudovirales is the dominant order, which is in line with the results of previous gut virome studies30,75. Additionally, we have detected CRISPR-Cas systems within the viral contigs. Specifically, of the 111,099 viral contigs, only 144 contained cas genes, and of these 144, only 20 possessed both CRISPR array and cas genes. Earlier studies have reported the existence of CRISPR-Cas systems in phages, conferring a survival advantage to the host organism32. Interestingly, 33% of these viral contigs were also found within a MAG constructed from the same dataset in our related study63, suggesting the possibility that the cas defense systems in these MAGs may have been acquired from the phages. Several CRISPR arrays within the viral contigs, lacking any cas genes, with the majority consisting of less than three repeats. In bacterial genomes, it is customary to exclude CRISPR arrays containing less than three repeats. However, a prior study has demonstrated the existence of mini-CRISPR arrays in viruses that lack cas genes33. Hence, we included CRISPR arrays with less than three repeats in our analysis. This resulted in finding 1,345 viral CRISPR arrays that contain fewer than three repeats. This might suggest a potential prevalence of mini-CRISPR arrays within gut phages.

Using GPD count data we showed that the alpha and beta diversity of the phage population statistically significantly differed between PD and control subjects. Furthermore, a previous research76 has shown differences in phage diversity between individuals with PD and controls, providing further support for our observed dissimilarities in alpha and beta diversity between the two groups. The observed differences in phage diversity suggest a potential role for the gut microbiome, and specifically bacteriophages, in the pathogenesis of PD. Bacteriophages can influence the composition and function of the gut microbiome by targeting specific bacterial species.

To deepen our understanding of this relationship and explore potential diagnostic or therapeutic applications, we were interested in developing a predictive machine learning model capable of identifying individuals at risk for PD based on phage population characteristics. The machine learning model exhibited promising predictive performance, achieving an AUC of 0.746 on cross-validation. These results suggest that the relative abundance of GPD phages can effectively discriminate between PD and control subjects. Notably, when tested on unseen data (external data) from a separate gut metagenomic study (ENA project PRJNA834801), our model demonstrated robust performance, achieving consistent scores of 0.8 across recall, precision, accuracy, and F1 score. The AUC of 0.74 on this external dataset closely mirrored the mean AUC from our cross-validation, reinforcing the model’s generalizability and potential real-world applicability. Interestingly, our attempt to simplify the model by using only the top 50 phages based on feature importance resulted in a lower AUC of 0.63 on the external data. This finding underscores the complexity of the gut-brain axis in PD and suggests that a more comprehensive approach, considering the entire GPD, is necessary for optimal predictive power. It implies that the relationship between gut phages and PD risk is not limited to a small subset of highly influential phages but rather involves a broader, more intricate microbial ecosystem. An earlier study75 reported creating a predictive model for PD detection based on gut microbiota virome data, achieving an impressive AUC score of 1.0075. Additionally, a previous analysis using the same samples as our study, but focusing on 16S bacterial community data, yielded a slightly lower score than our phage-based model2.

We aimed to identify possible phage genomes that would be differentially abundant among the PD group and the control group. Therefore, in addition to the diversity analysis, we also performed differential abundance analysis using the GPD database. Our results indicated that 1,866 phages were differentially abundant between PD and controls. It is noteworthy that a previous investigation reported no significant difference in prophage abundance between these two groups36. However, we recognized that database selection is a critical factor in assessing phage abundance. Specifically, we used the GPD, which encompasses 142,809 non-redundant gut phages. In contrast, the earlier study36 relied on a database of 760 phages. This marked disparity in database size and scope likely accounts for the differences observed between our study and the previous investigation. Another study, in turn, reported 241 significantly differentially abundant virus OTUs between two groups using a database with 45,033 dereplicated virus OTUs75.

Upon closer examination of our differentially abundant phages, we identified 824 phages that were significantly more abundant in PD patients and 1,042 that were more abundant in the control group. This balanced distribution suggests that PD is associated with both increases and decreases in specific phage populations, rather than a uniform shift in one direction. The taxonomic analysis of these differentially abundant phages revealed that the families Microviridae and Tectiviridae were more abundant in PD patients. Notably, a recent study77 reported an enrichment of Microviridae in the substantia nigra of PD patients, suggesting a potential link between gut microbiota and brain pathology. Our analysis of the host bacteria of these differentially abundant phages indicated that phages with hosts in the genera Bifidobacterium and Ruthenibacterium were more abundant in PD patients. Previous studies12 have reported high Bifidobacterium abundance in PD samples for this cohort. Consequently, the high abundance of Bifidobacterium phages may be directly correlated with the higher levels of this bacterial genus in PD. Interestingly, while Ruthenibacterium was not previously reported as differentially abundant in PD for this cohort, our findings suggest a potential role for Ruthenibacterium phages in PD. Therefore, both Ruthenibacterium and its associated phages emerge as intriguing targets for future investigations.

We computed the relative phage abundance of each sample by dividing the number of metagenomic reads mapping to phages by the total number of metagenomic reads. We then compared these relative abundances between the PD and control groups. Our findings reveal that no significant disparity exists between the two groups. Nevertheless, prior investigations have presented diverse outcomes regarding the relative phage abundance. Specifically, Bedarf et al.36 reported a decrease in total virus abundance in the PD group, while Mao et al.66 observed an increase in total virus abundance in PD. Hence, we conclude that phage specific abundance analysis may be more informative than the total phage abundance.

Recently, there have been reports of alternative genetic codes being utilized in phages, which may offer certain adaptive advantages34,35. To investigate genetic code usage within the GPD and our predicted viral contigs, we assessed the coding density of the phages. The most common standard code in both the GPD and our viral contigs was the standard code (code 11). For alternative code usage, we observed dramatic increases in coding density. For example, for the GPD phages that prefer to use code 15, the average coding density was 91% with code 15, while with the standard code it was only 63%. Applying an alternative genetic code during the annotation process can enhance the structural gene annotation for certain phages. It is noteworthy that the second most common genetic code in the GPD was code 4, whereas in our viral contigs it was code 15. It should be emphasized that coding density calculation is more accurate when the phage is complete or nearly complete35. We did not filter out non-complete phage contigs in our study, and most of the phages were categorized as "low quality draft". This difference in genetic code preference distribution between GPD phages and our phages may arise for this reason. Among the 1,866 differentially abundant phages identified between the control and PD groups, 824 were significantly more abundant in the PD group. Notably, four of these phages, which were significantly more abundant in the PD group, were also predicted to utilize genetic code 15. In contrast, none of the highly abundant phages in the control group were predicted to utilize code 15. This observation suggests that the prevalence of code 15 phages is notably higher in the PD group. The association between genetic code 15 and the increased abundance of these phages in PD raises intriguing questions about their potential role in the disease context. It is worth exploring whether the use of code 15 could be linked to specific interactions with the host or other environmental factors that are more prevalent or distinct in the PD group. Future studies should investigate the functional implications of this alternative genetic code usage and its potential impact on phage-host dynamics in PD.

Conclusion

Several studies have reported differences in the microbial composition of the gut microbiome in PD patients relative to controls78 and prodromal patients in a large risk cohort study79. Various strategies can be used to manipulate the gut microbiome, such as prebiotics, environmental factors, and physical activity, but antibiotics and probiotics are particularly effective in altering the microbial population structure in the gut. In addition, several studies have shown that the use of a combination of bacteriophages, known as a "cocktail of phage", can effectively modify the structural composition of the gut microbial community or even modify the genomes of specific microbes in living animals by editing80,81,82,83. In summary, this study provides evidence of changes in mobile genetic element populations in the gut microbiome of PD patients. It is possible that phages could serve as biomarkers or even as a treatment option if suitable phages are identified and isolated. However, this would require significant effort as identifying and isolating appropriate phages is a complex process.

Data availability

All sequencing data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession code PRJEB59350. The analysis codes can be found at https://github.com/icemduru/Parkinson_Disease_Gut_Microbiota_Phage_Plasmid_Diversity_ML.

References

Dorsey, E. R. et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology 68, 384–386 (2007).

Scheperjans, F. et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 30, 350–358 (2015).

Braak, H. et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 197–211 (2003).

Braak, H., de Vos, R. A. I., Bohl, J. & Del Tredici, K. Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci. Lett. 396, 67–72 (2006).

Cersosimo, M. G. & Benarroch, E. E. Pathological correlates of gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 559–564 (2012).

Mertsalmi, T. H. et al. More than constipation - bowel symptoms in Parkinson’s disease and their connection to gut microbiota. Eur. J. Neurol. 24, 1375–1383 (2017).

Perez-Pardo, P. et al. The gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease: Possibilities for food-based therapies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 817, 86–95 (2017).

Wang, H.-X. & Wang, Y.-P. Gut microbiota-brain axis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 129, 2373–2380 (2016).

Iannone, L. F. et al. Microbiota-gut brain axis involvement in neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Rev. Neurother. 19, 1037–1050 (2019).

Cryan, J. F., O’Riordan, K. J., Sandhu, K., Peterson, V. & Dinan, T. G. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 19, 179–194 (2020).

Blander, J. M., Longman, R. S., Iliev, I. D., Sonnenberg, G. F. & Artis, D. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat. Immunol. 18, 851–860 (2017).

Aho, V. T. E. et al. Relationships of gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, inflammation, and the gut barrier in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 16, 6 (2021).

Cryan, J. F. & Dinan, T. G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 701–712 (2012).

Bonaz, B., Bazin, T. & Pellissier, S. The agus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Front. Neurosci. 12, 49 (2018).

Aho, V. T. E. et al. Gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease: Temporal stability and relations to disease progression. EBioMedicine 44, 691–707 (2019).

Pereira, P. A. B. et al. Oral and nasal microbiota in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 38, 61–67 (2017).

Xie, A. et al. Bacterial butyrate in Parkinson’s disease is linked to epigenetic changes and depressive symptoms. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 37, 1644–1653 (2022).

Pereira, P. A. B. et al. Multiomics implicate gut microbiota in altered lipid and energy metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 8, 39 (2022).

van Kessel, S. P., Auvinen, P., Scheperjans, F. & El Aidy, S. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylase associates with clinical variables in a longitudinal cohort study of Parkinsons disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 7, 115 (2021).

Breitbart, M. et al. Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6220–6223 (2003).

Minot, S. et al. The human gut virome: Inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res. 21, 1616–1625 (2011).

Minot, S., Grunberg, S., Wu, G. D., Lewis, J. D. & Bushman, F. D. Hypervariable loci in the human gut virome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 3962–3966 (2012).

Minot, S. et al. Rapid evolution of the human gut virome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 12450–12455 (2013).

Hannigan, G. D., Duhaime, M. B., Ruffin, M. T., Koumpouras, C. C. & Schloss, P. D. Diagnostic potential and interactive dynamics of the colorectal cancer virome. MBio 9, e02248-e2318 (2018).

Yang, K. et al. Alterations in the gut virome in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology 161, 1257-1269.e13 (2021).

Leal-Rodríguez, C. et al. The infant gut virome is associated with preschool asthma risk independently of bacteria. Nat. Med. 30, 138–148 (2024).

Liang, G., Cobián-Güemes, A. G., Albenberg, L. & Bushman, F. The gut virome in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr. Opin. Virol. 51, 190–198 (2021).

Adiliaghdam, F. et al. Human enteric viruses autonomously shape inflammatory bowel disease phenotype through divergent innate immunomodulation. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabn6660 (2022).

Draper, L. A. et al. Autochthonous faecal viral transfer (FVT) impacts the murine microbiome after antibiotic perturbation. BMC Biol. 18, 173 (2020).

Camarillo-Guerrero, L. F., Almeida, A., Rangel-Pineros, G., Finn, R. D. & Lawley, T. D. Massive expansion of human gut bacteriophage diversity. Cell 184, 108-1109.e9 (2021).

Hille, F. & Charpentier, E. CRISPR-Cas: Biology, mechanisms and relevance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 371, 20150496 (2016).

Seed, K. D., Lazinski, D. W., Calderwood, S. B. & Camilli, A. A bacteriophage encodes its own CRISPR/Cas adaptive response to evade host innate immunity. Nature 494, 489–491 (2013).

Medvedeva, S. et al. Virus-borne mini-CRISPR arrays are involved in interviral conflicts. Nat. Commun. 10, 5204 (2019).

Peters, S. L. et al. Experimental validation that human microbiome phages use alternative genetic coding. Nat. Commun. 13, 5710 (2022).

Borges, A. L. et al. Widespread stop-codon recoding in bacteriophages may regulate translation of lytic genes. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 918–927 (2022).

Bedarf, J. R. et al. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med. 9, 39 (2017).

Wallen, Z. D. et al. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 13, 6958 (2022).

Qian, Y. et al. Gut metagenomics-derived genes as potential biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 143, 2474–2489 (2020).

Berardelli, A. et al. EFNS/MDS-ES/ENS [corrected] recommendations for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 16–34 (2013).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Yu, M. K., Fogarty, E. C. & Eren, A. M. Diverse plasmid systems and their ecology across human gut metagenomes revealed by PlasX and MobMess. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 830–847 (2024).

Eren, A. M. et al. Community-led, integrated, reproducible multi-omics with anvi’o. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 3–6 (2021).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat. Commun. 9, 2542 (2018).

Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Arango-Argoty, G. et al. DeepARG: A deep learning approach for predicting antibiotic resistance genes from metagenomic data. Microbiome 6, 23 (2018).

Sequeira, J. C., Rocha, M., Alves, M. M. & Salvador, A. F. UPIMAPI, reCOGnizer and KEGGCharter: Bioinformatics tools for functional annotation and visualization of (meta)-omics datasets. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 1798–1810 (2022).

Menzel, P., Ng, K. L. & Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 7, 11257 (2016).

Kieft, K., Zhou, Z. & Anantharaman, K. VIBRANT: Automated recovery, annotation and curation of microbial viruses, and evaluation of viral community function from genomic sequences. Microbiome 8, 90 (2020).

Nayfach, S. et al. CheckV assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 578–585 (2021).

Russel, J., Pinilla-Redondo, R., Mayo-Muñoz, D., Shah, S. A. & Sørensen, S. J. CRISPRCasTyper: Automated identification, annotation, and classification of CRISPR-Cas Loci. CRISPR J. 3, 462–469 (2020).

Zhang, R. et al. SpacePHARER: Sensitive identification of phages from CRISPR spacers in prokaryotic hosts. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 37, 3364–3366 (2021).

Guerin, E. et al. Biology and taxonomy of crAss-like bacteriophages, the most abundant virus in the human gut. Cell Host Microbe 24, 653-664.e6 (2018).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 10, 421 (2009).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10, giab008 (2021).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Zhu, A., Ibrahim, J. G. & Love, M. I. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: Removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 35, 2084–2092 (2019).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. (2012).

Abraham, A. et al. Machine learning for neuroimaging with scikit-learn. Front. Neuroinform. 8, 14 (2014).

Duru, I. C. et al. Metagenome-assembled microbial genomes from Parkinson’s disease fecal samples. Sci. Rep. 14, 18906 (2024).

Dutilh, B. E. et al. A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes. Nat. Commun. 5, 4498 (2014).

Hopfner, F. et al. Gut microbiota in Parkinson disease in a northern German cohort. Brain Res. 1667, 41–45 (2017).

Mao, L. et al. Cross-sectional study on the gut microbiome of Parkinson’s disease patients in central China. Front. Microbiol. 12, 728479 (2021).

Suzuki, Y. et al. Long-read metagenomic exploration of extrachromosomal mobile genetic elements in the human gut. Microbiome 7, 119 (2019).

Broaders, E., Gahan, C. G. M. & Marchesi, J. R. Mobile genetic elements of the human gastrointestinal tract: Potential for spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Gut Microbes 4, 271–280 (2013).

Kurokawa, K. et al. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res Int. J. Rapid Publ. Rep. Genes Genomes 14, 169–181 (2007).

Smillie, C. S. et al. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome. Nature 480, 241–244 (2011).

Odamaki, T. et al. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: A cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 16, 90 (2016).

Marshall, C. G., Lessard, I. A., Park, I. & Wright, G. D. Glycopeptide antibiotic resistance genes in glycopeptide-producing organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 2215–2220 (1998).

Nazzal, L. et al. Effect of vancomycin on the gut microbiome and plasma concentrations of gut-derived uremic solutes. Kidney Int. Rep. 6, 2122–2133 (2021).

Ding, Y. et al. PacBio sequencing of human fecal samples uncovers the DNA methylation landscape of 22 673 gut phages. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 12140–12149 (2023).

Tisza, M. J. & Buck, C. B. A catalog of tens of thousands of viruses from human metagenomes reveals hidden associations with chronic diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2023202118 (2021).

Tetz, G., Brown, S. M., Hao, Y. & Tetz, V. Parkinson’s disease and bacteriophages as its overlooked contributors. Sci. Rep. 8, 10812 (2018).

Zhao, Y. et al. The discovery of phages in the Substantia Nigra and its implication for Parkinson’s disease. 2024.07.13.603353 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.13.603353 (2024).

Boertien, J. M., Pereira, P. A. B., Aho, V. T. E. & Scheperjans, F. Increasing comparability and utility of gut microbiome studies in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Park. Dis. 9, S297–S312 (2019).

Berg, D. et al. Prodromal Parkinson disease subtypes—key to understanding heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 349–361 (2021).

Febvre, H. P. et al. PHAGE study: Effects of supplemental bacteriophage intake on inflammation and gut microbiota in healthy adults. Nutrients 11, 666 (2019).

Federici, S. et al. Targeted suppression of human IBD-associated gut microbiota commensals by phage consortia for treatment of intestinal inflammation. Cell 185, 2879-2898.e24 (2022).

Galtier, M. et al. Bacteriophages targeting adherent Invasive Escherichia coli strains as a promising new treatment for Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis 11, 840–847 (2017).

Brödel, A. K. et al. In situ targeted base editing of bacteria in the mouse gut. Nature 632, 877–884 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the personnel of the DNA Sequencing and Genomics Laboratory for running the NGS assays. We acknowledge the CSC—IT Center for Science, Finland, for computational resources, and the University of Helsinki Language Services for English language revision. T.K.S. was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF22OC0080109).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.C.D., A.L., P.A.B.P., and P.A. conceived and designed the study. F.S. performed clinical evaluation of the patients. P.A.B.P provided statistical support. I.C.D, A.L., T.K.S., P.L., and J.S. analyzed the sequencing data. L.P organized NGS assays. I.C.D and A.L. and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

F.S. received grants from the Academy of Finland, the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa, the OLVI Foundation, Konung Gustaf V:s och Drottning Victorias Frimurarestiftelse, the Wilhelm and Else Stockmann Foundation, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation and the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, Renishaw. Honoraria: AbbVie, Axial Biotherapeutics, Orion, GE Healthcare, Merck, Teva, Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Biocodex, Lundbeck, and Biogen. FS is the founder and CEO of NeuroInnovation Oy and NeuroBiome Ltd. and is a member of the advisory boards of Axial Biotherapeutics and MRM Health. He has stock options from Axial Biotherapeutics. P.A.B.P., L.P., P.A., and F.S. have patents issued (FI127671B, US10139408B2, US11499971B2) and pending (US16/186,663, EP3149205) that are assigned to NeuroBiome Ltd. T.K.S. was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF22OC0080109). The rest of the authors (I.C.D, A.L., P.L, and J.S) declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duru, I.C., Lecomte, A., Laine, P. et al. Comparison of phage and plasmid populations in the gut microbiota between Parkinson’s disease patients and controls. Sci Rep 15, 13723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96924-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96924-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Revamping Parkinson’s disease therapy using PLGA-based drug delivery systems

npj Parkinson's Disease (2025)

-

The usefulness of microbiome profiling for geriatric patients with neuropsychiatric conditions: a scoping review

Translational Psychiatry (2025)