Abstract

This research aimed to investigate the influence of free radicals on the wettability of Guizhou anthracite coal. The best acid modifier was selected through quantum chemistry and sedimentation experiments. Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR), and wetting heat experiments were carried out to investigate the effect of acid modifiers on the wetting properties of coal. The results of the study show that, among the three modifiers tested (APG, AEO3, and NP-10), alkyl glycoside (APG) exhibited the best wetting performance and strongest reactivity with the coal molecules. The best wetting effect was achieved with 1% APG + 6% HF. The acid modifier increased the concentration of hydrophilic functional groups and free radicals. Under the action of the acid modifier, the hydrophobic functional groups in the coal samples break off to form active sites (free radicals) and then continue to be converted into hydrophilic functional groups, which in turn improves the wettability of the coal samples. The measured wetting heat of the post-modified experimental coal sample increased by 14.86%, which proved that the acid modifier could improve the wettability of the coal. This study provides theoretical insights into the quantum chemical optimization of modifiers, gas disaster prevention, and dust management of anthracite coal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wettability is an important characteristic of the interaction between coal and liquid/gas, and the wettability of coal seams is closely related to dust reduction, explosion prevention, and gas disaster control in coal mines, which has been a hot spot of research. Guizhou is rich in coal resources, containing medium- and high-metamorphic coals, mostly anthracite, with poor wettability of the coal seams, making the management of coal dust and gas disasters difficult. Therefore, improving the wettability of coal seams in the Guizhou mining area is crucial for safe mining of coal resources.

Currently, surfactants are some of the most commonly used reagents for improving the wettability of coal seams. Li et al.1 carried out methane desorption experiments and wettability tests with the help of typical long-flame coals and found that surfactants not only improved their wettability but also promoted the desorption of methane from the coals. Wang et al.2 used alkyl polyglucosides and polyacrylamide to treat coal samples, which increased the wettability of the coals and decreased the force of interaction between the coal samples and methane. After the treatment of coal samples with alkyl glycosides and polyacrylamide, the wettability of coal samples was enhanced, the interaction force between them and methane was reduced, and the methane desorption in coal samples was increased; in addition to the surfactants, the acid solution also improved the wettability of coal and promoted the desorption of gas in coal. Zhang et al.3 used HF to treat anthracite coal in the Guizhou mining area and found that acid improved the wettability of the experimental coal samples and reduced their gas adsorption capacity. The principle of coal seam acidification technology4,5,6 involves the injection of an acid into the reservoir, which reacts with the minerals therein, dissolving the minerals filling the pores of the reservoir, and changing the physical and chemical properties of the reservoir. Oxygen-containing functional groups and pore volume alter the primary and secondary adsorption of water molecules by coal, respectively7,8, which can increase the content of oxygen-containing functional groups and improve the pore volume in coal, which together respond to and improve the wettability of coal9.

However, conventional acidification measures often have shortcomings, such as fast acid–rock reaction speed, limited area of action, and insufficient reaction. Based on this, some researchers have used modifiers as acid additives to optimize conventional acidification measures. Guanhua et al.10 added modifiers into the mixed acid solution composed of hydrochloric acid and hydrofluoric acid, which enhanced the dissolution of minerals in the coal samples. The modifiers expanded the reaction surface area between the acid and the minerals within the coal rock pore cracks, resulting in a more through and complete acid-rock reaction. Hongchao et al.11 found that the modifier can promote acid dissolution of minerals and synergistically improve the pore connectivity of the coal body. Jingna et al.12 used acid treatment with a modifier to treat coal samples and found that the modifier not only synergistically enhances the effect of acid, but also promotes the “ion-exchange effect,” which can significantly reduce the mineral content, increase the hydroxyl content of coal, and change the chemical structure of the coal samples. In conclusion, the modifier improved the acidification of coal by cooperating with an acid solution. However, several types of modifiers exist, and if the selected modifier is not compatible with the acidic solution, the antagonistic effect between the two weakens the acidification effect. Therefore, it is essential to select modifiers with synergistic acidification effects. Modifiers are special molecular structures with two terminal groups (hydrophilic/hydrophobic) that can alter the hydrophilic/hydrophobicity of solids. Currently, the selection of modifier monomers is usually accomplished using sedimentation tests13,14, contact angle tests15,16, and surface tension determination tests17,18. However, the settling time in the sedimentation experiment mainly relies on the visual determination of the tester; contact angle measurement is affected not only by the droplet height, droplet size, and measurement time but also by the contact angle hysteresis phenomenon; and the liquid concentration, nature, and temperature affect the surface tension test results. Therefore, for the process of selecting a modifier monomer, a more scientific and advanced method is urgently required.

Wettability is one of the main properties of coal surfaces and is affected by several factors. For example, oxygen-containing functional groups will form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which will enhance the ability of the coal surface to adsorb water molecules, thereby improving its wettability19,20. The electrical properties of the coal surface are related to the oxygen-containing functional groups in the coal, and the more oxygen-containing functional groups there are, the stronger the negative electrical property of coal is, and the better the wettability of coal is21,22. The roughness of the surface affects the free energy of the surface, and the wettability of coal is positively correlated with free energy23. Minerals are associated resources of coal, and the type of minerals affects the wettability of the coal surface, e.g., the presence of quartz improves the wettability of coal24,25,26. Although several factors affect the wettability of coal rocks, there is a consensus that the type and content of functional groups in coal are the main influencing factors27. Free radicals are key parameters affecting the low-temperature oxidation of coal and can be used to determine the degree of oxidation and spontaneous combustion mechanism of coal. Both free radicals and functional groups are reactive groups of coal, and a change in the functional groups of coal has a significant effect on the chain reaction of free radicals in coal under the effects of light and heat. The correlation between free radicals and functional groups has been confirmed in the field of spontaneous coal combustion28, and research on free radicals is more extensive in this field29,30. However, in the study of coal rock wettability, the effects of acid and modifier compounding on the wettability of coal rock and their correlation with functional groups from the perspective of free radicals have rarely been reported. Therefore, the influence of free radicals on the wettability of coal rock under the effects of acid and modifier compounds must be investigated.

To reveal the response mechanism of the modifier synergistic acid to the wettability of anthracite coal, taking anthracite coal in the Guizhou mining area as the research object, we performed quantum chemistry and sedimentation experiments to optimize the modifier and the compounding liquid. We employed infrared spectroscopy, paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and wetting heat experiments to interpret the evolution law of the functional groups and free radicals in the coal and to validate the effect of the modifier synergistic acid in wetting and modification to lay theoretical foundations for the engineering application of the acidizing technology to improve the wettability of coal seams in Guizhou mining area.

Material preparation and experimental methods

Coal sample preparation and reagent selection

Coal sample preparation

The experimental coal samples were obtained from the M9 coal seam of the Guizhou Qianbei Coalfield, which is anthracite coal. The coal samples were selected from the working face with large lumps and little gangue, sealed and preserved at the sampling point, and then transported to the laboratory after crushing, grinding, and vibration sieving. Coal powder with particle sizes between 0.150 and 0.075 mm was screened for the sedimentation experiment; the coal powder with particle size < 0.075 mm was selected for the infrared spectroscopy experiment; the coal powder with particle size between 0.180 and 0.250 mm was selected for the paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy experiment; and the coal powder with particle size < 0.038 mm was selected for the wetting heat determination experiment. After the above coal samples were prepared, they were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h and stored in sealed containers.

Acid and modifier selection

A previous study showed that 6% hydrofluoric acid (6% HF) can improve the wettability of coal3. He31 carried out an acidification condition preference experiment using the same coal samples used in this study and found that 6% HF had an optimal acidification effect when the acidification treatment was 24 h. Therefore, 6% HF was chosen as the main acid in this study, and the acidification time was 24 h.

A modifier is a special molecular structure with two end groups (hydrophilic/hydrophobic groups) that can change the solid surface properties under specific circumstances and has a good synergistic acidification effect. Common modifiers are cationic, anionic, nonionic, and amphoteric, among which nonionic modifiers have better wettability, compatibility, and synergistic effects32,33. To obtain the best modifier for synergization with the main acid solution, three nonionic modifiers, alkyl glycoside (APG), fatty alcohol ethoxylate (AEO3), and nonylphenol ethoxylate (NP-10), were screened as the proposed modifiers, and their related parameters are listed in Table 1.

Simulation methodology

Model construction and optimization

The anthracite model constructed by the team using the experimental coal samples and verified by density was selected34, and the model was named WYM. Based on the molecular structure parameters of the modifier molecules in Table 1, a three-dimensional model was constructed using the Visual module of the Materials Studio software. The constructed model was optimized using the geometry optimization task in the DMol3 module. The optimized water, coal, and modifier molecular models are shown in Fig. 1.

Quantum chemical calculations

Quantum chemistry allows for the calculation of relevant parameters for different types of modifiers and the initial selection of modifier monomers. The optimized molecular model was subjected to electrostatic potential and forward-orbital energy calculations using the DMol3 module. Electrostatic potential was used to determine the wettability of the modifier molecules, and frontline orbital energy was used to analyze the reactivity of the modifier molecules.

Experimental methods

Sedimentation experiment

We added 0.50 g of coal powder with a particle size of 0.150–0.250 mm to 100 mL of solution and poured the solution into the beaker. The starting time from when the coal powder came into contact with the liquid surface until the coal powder was completely submerged below the liquid surface was recorded, i.e., which was recorded as the time of settling of the coal sample.

Infrared spectroscopy experiment (FTIR)

A Nicolet iS10 FTIR spectrometer was used to determine the surface functional groups of the experimental coal samples. The coal samples with a particle size < 0.075 mm were poured into the experimental reagents and stirred well, soaked for 24 h, filtered, and dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

Paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy experiment (EPR)

The Bruker EMXplus type paramagnetic resonance spectrometer was used to determine the free radicals in the experimental coal samples, and the mass of the experimental coal samples was 0.01 g.

Wetting heat determination experiment (C80)

A C80 membrane mixing cell microcalorimeter was used to determine the wetting heat of experimental coal samples, the experimental temperature was set to 30℃, the mass of experimental coal samples was 0.05 g, and the wetting liquid was 2.5 mL deionized water.

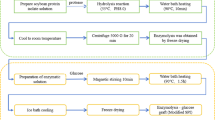

The experimental flow of this study is shown in Fig. 2:

Determination of acid modifiers

Quantum chemical primary selection of modifiers

Wetting performance assessment

The electrostatic potential (ESP) can be used to determine weak intermolecular interactions35. In this study, the electrostatic potential of the water molecules, coal molecules, and each modifier was calculated using the Dmol3 module, as shown in Fig. 3. When the positive value of the electrostatic potential of a molecule is larger, its positive potential is stronger; when the negative value (absolute value) of its electrostatic potential is larger, its negative potential is stronger.

Research shows that36, through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic bonding cooperation, the modifier formed a hydrophilic head group toward the aqueous solution, the hydrophobic tail group was adsorbed on the surface of the coal directional adsorption structure, and the surface tension of the solution was rapidly reduced. In other words, when the potential difference between the negative potential of the hydrophilic head group of the modifier and the positive potential of the water molecule and the potential difference between the positive potential of the hydrophobic tail group of the modifier and the negative potential of the coal molecule are larger, it is easier to form a hydrogen bond between the hydrophilic head group of the modifier molecule and the water molecule, and it is easier to form a directional adsorption layer on the coal surface, which can fully exploit the wetting and modifying effect of the modifier and improve the wettability of the coal sample.

The electrostatic potentials of the hydrophilic head group and hydrophobic tail group of the water molecules, coal molecules, and three modifier molecules are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that the potential difference between the negative potential of the hydrophilic head group on the molecular surface of the modifiers APG, AEO3 and NP-10 and the positive potential of the H2O molecule were 0.12942 a.u., 0.12914 a.u. and 0.12396 a.u., respectively. The potential difference of APG was the largest, which indicated that its hydrophilic head group was more prone to form hydrogen bonds with the H2O molecule. The potential differences between the positive potential of the hydrophilic tail group on the molecular surface of the three modifier molecules and the negative potential of the WYM molecule were 0.07236 a.u., 0.06608 a.u. and 0.06990 a.u., respectively, which indicates that the hydrophobic bonding between the hydrophobic tail group of the APG and the negative potential region on the surface of the WYM molecule is the strongest. In conclusion, among the three modifiers, APG can better form a directional adsorption structure in solution with a hydrophilic head group toward water and a hydrophobic tail group toward coal and has the best wetting effect on the experimental coal samples.

Reactivity analysis

According to molecular orbital theory, the highest occupied orbital energy (HOMO) is related to the ability of a molecule to donate electrons, and the lowest unoccupied orbital energy (LUMO) is related to the molecule’s ability to accept electrons. Zhang et al.37 showed that when the EHOMO of the modifier molecule is higher, its ability to donate electrons is stronger, whereas when the ELUMO of the modifier molecule is lower, it is easier for it to accept electrons. Both the LUMO and HOMO affect the reactivity of the modifier molecules.

The distributions of the frontline orbitals on the surface of the coal molecule and the three modifier molecules were obtained by simulation using the Dmol3 module, and the results are shown in Fig. 4.

The energy level difference between molecules (ΔE = ELUMO − EHOMO) can be used to determine the stability of molecules, and the smaller the value, the less stable and more reactive the molecule is38. Kenichi Fukui’s frontline orbital theory shows that when the absolute value of the energy level difference between two molecules is less than 0.2206 Ha, the electrons between the molecules are prone to jump. The smaller the energy level difference, the greater the strength of the intermolecular interactions, and the easier it is for the two molecules to undergo chemical reactions.

To analyze the reactivity of the three modifiers APG, AEO3, and NP-10 themselves and to compare the interaction strengths between the three modifier molecules and the coal molecule, the energy level difference between the LUMO and HOMO of the modifier molecule itself (ΔE1) and between the LUMO of the modifier molecule and the HOMO of the coal molecule (ΔE2) were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2)39,40.

where ΔE1 is the energy level difference between the LUMO and HOMO of the modifier molecule itself; ΔE2 is the energy level difference between the LUMO of the modifier molecule and the HOMO of the coal molecule; \(E_{LUMO}^{{C{\text{oal}}}}\) and \(E_{HOMO}^{{C{\text{oal}}}}\) are the LUMO and HOMO energy values of the coal molecule, respectively; and \(E_{LUMO}^{{{\text{GXJ}}}}\) and \(E_{HOMO}^{{{\text{GXJ}}}}\) are the LUMO and HOMO energy values of the modifier molecule, respectively.

The calculated results of HOMO, LUMO, ΔE1, and ΔE2 for the coal molecule and the three modifier molecules are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5a shows that the HOMO energies of APG, AEO3, and NP-10 do not differ much, indicating that the electron-donating abilities of the three are similar. However, the difference in the LUMO energies of the three was more obvious, and that of APG was the smallest, at only 4.57% and 4.66% of the corresponding values of AEO3 and NP-10, respectively, indicating that APG had the largest ability to accept electrons. As shown in Fig. 5b, among the three modifiers, APG itself has a lower energy level difference ΔE1, indicating that it is less stable and has a stronger molecular reactivity than AEO3 and NP-10. The energy level difference ΔE2 of the three modifiers is less than 0.2206 Ha, which indicates that all three are capable of undergoing electron jumps with coal molecules. However, the energy level difference ΔE2 of APG is smaller than those of AEO3 and NP-10, which indicates that it has a higher degree of interaction with coal molecules, and electron transfer, bond combination, or bond breakage between APG and coal molecules become easier.

In summary, the wetting properties and reactivity of APG were better than those of AEO3 and NP-10, and its degree of interaction with the coal samples was stronger, making it more likely to undergo chemical reactions. Subsequently, APG was compounded with 6% HF to explore the synergistic acid-wetting modification effect between APG and acid.

Optimization experiment of modifier and acid compounding

Using the aforementioned preliminary quantum chemical selection of APG with strong wettability and reactivity and 6% HF compounding, we obtained a modifier concentration with the best synergistic 6% HF wettability modification effect. The volume fractions of the preliminary modifier APG were set as 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1% and were compounded with 6% HF. The solution system with the best wetting effect was selected through a sedimentation experiment after compounding the modifier and acid solution.

The settlement experiment can visualize the effect and characteristics of the solution system in wetting the coal samples, that is, the faster the settlement time of the coal samples, the lower the surface tension of the solution system, and the better the wetting effects on the coal samples. The settling times of the coal samples in the solution system composed of 5 volume fractions of APG and 6% HF are shown in Fig. 6.

As shown in Fig. 6, the settling time of the coal samples in the compound solution decreased with an increase in the volume fraction of APG because of the directional arrangement of the molecules of the APG modifier in the compound solution. This substantially reduced the surface tension of the compound solution, resulting in the enhancement of the wetting ability of the compound solution and the obvious settling effect of the coal samples. These results show that the APG modifier enhances the wetting ability of the compound solution, which is consistent with the electrostatic potential simulation results.

Figure 6 shows that when a volume fraction of 0.2%–0.4%APG was added to the acid solution, the settling time of the coal sample was significantly shortened because of the rapid adsorption of a large amount of APG on the surface of the coal sample, resulting in a significant reduction in the contact angle between the coal sample surface and the solution. When the volume fraction of APG is 0.4%–0.1%, the settling time of coal sample does not considerably change. This is because the adsorption amount of APG on the surface of the coal sample is gradually saturated; thus, the settling time of the coal sample in the mixed solution did not change significantly. In the range of the APG volume fraction measured in the experiment, the settlement time of the coal sample after the APG and 6%HF combination was 0.2% > 0.4% > 0.6% > 0.8% > 1% in order from largest to smallest; that is, the settlement time of the experimental coal sample in the 1%APG + 6%HF mixture solution was the shortest, and the wetting effect was the best.

To investigate the wetting mechanism of the acid modifier on the anthracite, an optimal compound solution (1%APG + 6%HF) was selected to treat the coal samples. The optimal compounding solution was then called the acid modifier, and the coal samples treated with the optimal compounding solution were called after-modified experimental coal samples, whereas the coal samples that were not treated with the optimal compounding solution were called before-modified experimental coal samples.

Experimental results and discussion

Characteristics of chemical structure evolution of coal samples

Characteristics of functional group changes in coal

The type and number of functional groups on the coal surface affect the surface wettability27 to a certain extent. The absorption peaks of the functional groups were used to characterize the chemical structure of the coal, and the effect of the acid modifier on the wettability of the experimental coal samples was investigated. The FTIR spectra of the experimental coal samples before and after modification were obtained using infrared spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 7.

Peakfit software was used to fit the peaks of the aromatic structures (700–900 cm−1), oxygenated functional groups (1000–1800 cm−1), fatty structures (2800–3000 cm−1), and hydroxyl functional groups (3000–3600 cm−1) in the FTIR spectra of the experimental coal samples5,41.

-

(1)

Aromatic structure (700–900 cm−1).

The results of peak fitting for the aromatic structure of the experimental coal samples are shown in Fig. 8.

The 700–900 cm−1 region in the FTIR spectrum can be attributed to aromatic structures, reflecting the different degrees of substitution of the aromatic groups42. As shown in Fig. 8, the aromatic content of the experimental coal sample before modification was 1.47 times that of the post-modified coal sample, indicating that the aromatic content of the experimental coal samples was reduced after modification. Among them, benzene ring monosubstitution and benzene ring disubstitution were both reduced, with decreases of 13.54% and 56.83%, respectively; the benzene ring trisubstitution was increased, with an increase of 14.44%. Notably, benzene ring tetra-substitution appeared in the post-modified experimental coal sample, whereas the benzene ring penta-substitution disappeared completely. The above results show that the aromatic structure of the post-modified experimental coal sample is more complex, which may be due to the decomposition and cleavage of aromatic substances on the aliphatic chain of the experimental coal samples under the action of an acid modifier, which leads to a change in the substitution of the benzene ring19.

-

(2)

Oxygen-containing functional groups (1000–1800 cm−1).

The results of peak fitting of the oxygen-containing functional groups of the experimental coal samples are shown in Fig. 9.

Various oxygen-containing functional groups exist. These groups are closely related to the wettability of the coal surface43,44. As shown in the fitting results in Fig. 9, the oxygen-containing functional group content in the post-modification experimental coal sample increased by 126.72%. Among them, the wave number near 1060 cm−1 is attributed to the alkyl ether C–O–C, and this oxygen-containing functional group appeared in the post-modified experimental coal sample; the wave number near 1080–1270 cm−1 can be attributed to the C–O bonds. The peak area in this region increased by 42.50% after the modification; the wave number near 1630–1640 cm−1 is attributed to the C=O bonds, and the peak area in this part increased by 123.42%. The above results indicate that the number of oxygen-containing functional groups in the post-modification coal sample increased, which may have affected its wettability.

-

(3)

Aliphatic structure (2800–3000cm−1).

The split-peak fitting results for the aliphatic structures of the experimental coal samples are shown in Fig. 10.

In the FTIR spectrum of coal, the wavenumber in the region of 2800–3000 cm−1 belongs to the aliphatic structure, which is mainly caused by the –CH, –CH2, and –CH3 telescopic vibrations, which can be divided into two types: symmetric telescopic vibration and asymmetric telescopic vibration. As shown in Fig. 10, the symmetric stretching vibrations of –CH3 and –CH2 in the modified coal samples decreased by 85.95% and 37.84%, respectively, with little change in the symmetric stretching vibration of –CH. The asymmetric stretching vibrations of –CH2 and –CH3 decreased by 48.44% and 71.37%, respectively. Compared to the experimental sample before modification, the absorption peak area of the –CH3 stretching vibration in the post-modified sample was significantly reduced. The above results indicate that the branched chains of the modified coal sample were destroyed and the fat structure was reduced.

-

(4)

Hydroxyl functional group (3000–3600 cm−1)

The results of peak fitting of the hydroxyl functional groups of the experimental coal samples are shown in Fig. 11.

The hydroxyl group is an oxygen-containing functional group with excellent hydrophilicity17. After treatment with the acid modifier, the hydroxyl content of the experimental coal samples increased by 83.75%. The fitting results in Fig. 11 show that the peak areas of ring hydrogen bonds, hydrogen bonds formed by self-conjugated hydroxyl groups (OH–OH), hydrogen bonds formed by hydroxyl groups and oxygen in ether (OH–O), and hydrogen bonds formed by hydroxyl groups and π-bonds (OH-π) of coal samples increased after modification, and the former two peak areas (ring hydrogen bonds and OH–OH) increased more, with increases of 196.53% and 116.47%, respectively. The hydroxyl groups in the coal samples before and after modification were mainly formed by the hydrogen bonds of the self-consolidated hydroxyl groups, and the percentage of the peak area was more than 45%. The above results show that the hydroxyl group content in the experimental coal samples increased under the action of the acid modifier, and the wettability of the coal samples was enhanced.

The content of hydrophobic functional groups (aromatic and aliphatic structures) in the experimental coal samples decreased by 50.33%, and that of hydrophilic functional groups (oxygenated functional groups and hydroxyl structures) increased by 88.96% under the action of the acid modifier, which improved the wettability of the experimental coal samples. The hydrophobic functional group content of the experimental coal samples decreased because under the action of the acid modifier, small molecules such as aromatic and alkane branched chains in the coal were cleaved off, and the macromolecular structure of the coal was destroyed, resulting in a decrease in the hydrophobic functional group content. The hydrophilic functional group content considerably increased because the HF and APG in the acid modifier can undergo a chemical reaction on the surface of the coal samples, forcing the weak bonds in the basic structural unit of the coal surface to break, forming oxygen-containing functional groups with the oxygen in organic matter. In contrast, APG itself not only has good wetting properties, but also has the ability to synergize with acidification, which strengthens the effect of the acidification and wetting modification of the HF solution, leading to significant changes in the functional groups in the coal.

Characterization of free radical evolution in coal

Under certain conditions (such as thermal decomposition, force crushing, coal formation process, external environment, and other influencing factors), the breakage of the covalent bonds of macromolecules in the coal body and molecular cleavage results in the generation of atoms, molecules, or groups of unpaired electrons, which are known as free radicals. Research45 has shown that free radicals have strong chemical reactivity and can react with other substances to form new free radicals, reflecting the chemical structure of the coal body through free radicals.

-

(1)

EPR spectra, Lund factor g and line width ΔH

The EPR spectra of the experimental coal samples before and after modification were measured by paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 12a. The signal intensity of the EPR peaks of the experimental coal samples after modification was larger than that of the experimental coal sample before modification, and the position of the paramagnetic center of the paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) patterns shifted to the left, indicating that the free radicals of the experimental coal samples under the action of the acid modifier considerably changed. The Lund factor g and line width ΔH of the experimental coal samples were obtained by analyzing the EPR patterns, as shown in Fig. 12b and c, respectively.

The Lund factor, g, is an intrinsic property of the molecular structure of free radicals that can characterize the types and complexities of free radicals in coal46. It generally varies in the last three digits of the value of 2.00229. Figure 12b shows that the Lund factor of the post-modification experimental coal sample increased from 2.002625 to 2.002677, which indicates that the types of free radicals within them have increased and are more complex. The linewidth ΔH is the difference between the values of the horizontal coordinates corresponding to the peaks and valleys in the EPR patterns, which can not only characterize the symmetry of free radicals in coal (the linewidth ΔH is positively correlated with the symmetry of free radicals), but also reflect the degree of interactions between free radicals or between free radicals and the microcrystalline structure of the coal47. As shown in Fig. 12c, the linewidth ΔH of the post-modification coal sample slightly increased, indicating that the symmetry of free radicals in this coal sample was enhanced, and the degree of interaction between radicals and free radicals or between free radicals and microcrystalline structures in coal increased.

-

(2)

Free radical concentration (Ng)

The concentration of free radicals refers to the number of unpaired electron atoms, molecules, or groups per unit mass of the coal sample. Free radicals can be divided into primary radicals and newborn radicals according to the order of generation, and into stable radicals and active radicals according to their properties. The free radical concentration Ng in the experimental coal samples was calculated using Eqs. (3–4)48,49.

where Am denotes the quadratic integral area of the EPR patterns of the experimental coal sample; Nm denotes the spin number of the experimental coal sample; g denotes the Lund factor g; β denotes the Bohr magneton, β = 9.274 × 10–24 J/T; S is the spin quantum number, S = 1/2; ℎ is Planck’s constant, ℎ = 6.626 × 10−34 J·S, ħ = ℎ/2π; ℎ1 is the amplitude of the microwave field, Gs; ω is the microwave frequency, ω = 2πƒ, ƒ = 9059 × 106 s−1; k is the Boltzmann’s constant, k = 1.380649 × 10–23 J/K; and T is the measured temperature, 295 K. Ng is the concentration of free radicals per unit mass of the sample (spin/g) and m is the sample mass (g).

The calculated results for the free radical concentration of the experimental coal sample are shown in Fig. 13.

The generation and consumption of free radicals is a chain reaction, that is, the generation of newborn free radicals is accompanied by the obliteration of primary free radicals50. The calculation results in Fig. 13 show that the experimental coal sample before modification contains a certain amount of native free radicals, which should be the more stable free radicals generated in the process of coal formation. After treatment with the acid modifier, the concentration of free radicals in the experimental coal samples increased from 4.08220 × 1018 spin/g to 4.19164 × 1018 spin/g, and the concentration of the free radicals increased, which may be the result of the chemical reaction between the acid modifier on the surface of the experimental coal samples or inside the experimental coal samples. This may be due to the chemical reaction of the acid modifier on the surface or inside the experimental coal samples, which led to the breakage of the covalent bond of coal macromolecules and the shedding of side-chain molecules, thereby generating a large number of nascent radicals. Furthermore, the generation rate of nascent radicals in the experimental coal samples under the action of the acid modifier was greater than the obliteration rate of primary radicals, resulting in an increase in their radical concentration. In addition, the acid modifier activated the primary radicals in the coal, the reaction activity was enhanced, and the primary free radicals reacted with other substances to form nascent radicals.

Correlation of free radicals, functional groups, and wettability

The chemical structure of coal, which is closely related to the wettability of the coal body, includes free radicals and functional groups, indicating that the correlation between free radicals and functional groups is crucial for the change in wettability. Through joint FTIR and EPR analyses, we found that the content of aromatic and fatty structures of the experimental coal samples decreased under the effect of the acid modifier, the oxygenated and hydroxyl functional groups increased, and the type and concentration of free radicals in the coal increased, indicating that the increase in free radicals and the change in functional groups might be related to a certain extent.

Oxygen-containing functional groups are substances that promote reactivity, and the chemical behavior of the coal surface is mainly controlled by oxygen-containing functional groups51,52, which form hydrogen bonds with water molecules through the dipole force, generating a stable hydration film on the surface of the coal and weakening the hydrophobicity of the surface of the coal samples53. The FTIR analysis results indicated that under the effect of the acid modifier, the aromatic substances in the experimental coal samples may be decomposed and cracked, the aromatic structure may have become more complex, and the molecular structure may have become disordered and loose. However, the overall increase in the oxygen-containing functional groups of the experimental coal samples increased the reactivity on the surface of the coal samples, and the wettability could be improved. The results of the EPR test showed that the concentration of free radical Ng in the modified coal samples increased, the symmetry of the free radicals was enhanced, and the nascent free radicals originated from intermolecular covalent bonds and bridge bond breakage with higher activity. An essential aspect of free radicals is their active sites54,55,56. In this study, after treating the experimental coal samples with an acid modifier, a large number of active sites (i.e., free radicals) were formed after the fracture and detachment of hydrophobic functional groups (i.e., aromatic and aliphatic structures), which evolved into hydrophilic functional groups (i.e., oxygen and hydroxyl functional groups) under the assistance of the acid modifier. These reactive sites evolved into hydrophilic functional groups (i.e., oxygenated and hydroxyl functional groups) with the help of an acid modifier, which caused a change in the wettability of the coal samples. Notably, the acid modifier used in the experiments was a combination of HF and APG, which contained a large amount of oxygen in its molecular structure and provided favorable conditions for the conversion of active sites into oxygen-containing functional groups. Research57 showed that the wettability of coal samples is positively correlated with their radical concentration, and when the concentration of radicals in coal is higher, the contact angle of the coal samples is smaller, that is, the wettability of the coal samples is better. In this study, after treating the experimental coal samples with an acid modifier, the concentration of free radicals increased, which was favorable for reversing the wettability of the coal samples.

In summary, there was a certain transformation relationship between free radicals (active sites) and functional groups, and the enhancement in the wettability of the post-modified coal sample was related to the changes in free radicals and functional groups. The relationship between the free radicals, functional groups, and wettability under the action of an acid modifier is shown in Fig. 14.

Determination of the wetting heat of coal samples

Additional parameters can be used to characterize the wettability of the coal surface, including the contact angle, free energy, surface tension, and heat of wetting. The heat of wetting is widely used because of its high accuracy58,59. Wetting heat is the heat released in the process of the solid being wetted by liquid60, and when coal and water interact, the weak interaction between coal and water breaks the equilibrium state between the water and heat is released. The larger the absolute (negative) value of the heat of wetting, the easier it is for the surface of the coal sample to be wetted by water; the strength of the coal-water interaction is greater than that of the water interaction, and the surface of the coal sample is hydrophilic61. The wetting heat measurements of the experimental coal samples are shown in Fig. 15.

The generation of wetting heat is the result of deionized water adsorption on the surface of coal samples, and its magnitude is related to various factors, such as hydrophilic minerals and the type and content of functional groups62. As shown in Fig. 15, the wetting heat of the experimental coal samples before and after modification was negative because the experimental coal samples contained hydrophilic functional groups and silicate minerals.

The average value of the heat of wetting of the modified experimental coal samples was − 2.782 J/g, with an increase of 14.86%, indicating that the interaction between the modified experimental coal samples and deionized water was enhanced, the absolute value of the heat of wetting was increased, and the wettability was enhanced. The heat generated when the deionized water interacted with the post-modification experimental coal sample may have increased because of two reasons: first, the hydrophobic functional groups of the post-modification experimental coal sample were reduced and the hydrophilic functional groups were increased. When the deionized water contacted the surface of the post-modification experimental coal sample or was immersed in the interior, the deionized water reacted with it more easily, destroying the surface structure of the coal, breaking and rearranging the interatoms, and thus releasing more heat. Second, after the experimental coal samples were treated with the acid modifier, the types of free radicals in the coal increased, the concentration of free radicals increased, and numerous active sites could be observed on the surface of coal. Thus, the experimental coal samples interacted with the deionized water with higher intensity, and the amount of heat released increased.

The results of the wetting heat measurements of the experimental coal samples also confirmed the correctness of the analysis of the previous results. On the one hand, the results of quantum chemical analysis in section “Quantum chemical primary selection of modifiers” (judgment of wettability and reactivity analysis of modifier) were confirmed: APG can form a directional adsorption structure with hydrophilic head groups toward water and hydrophobic tail groups toward coal in the solution, and exerts its wetting effect; the energy difference ΔE1 between APG itself and ΔE2 between APG and coal is lower, which indicates that APG interacts with a higher degree with coal, and the chemical reaction between the two can easily occur. On the other hand, the influence of the chemical structure evolution characteristics on the wettability of the experimental coal samples under the effect of acid modification was confirmed. The hydrophobic functional groups decreased and the hydrophilic functional groups increased in the experimental coal sample after modification, and the types and concentrations of free radicals in the coal increased, which resulted in an increase in the wettability.

Conclusion

Using anthracite coal from the Guizhou mining area as the research object, we chose the optimal acid modifier using quantum chemistry and sedimentation experiments, including infrared spectroscopy, paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and wetting heat experiments, to clarify the wetting mechanism of the acid modifier on anthracite coal. The following conclusions were obtained:

-

(1)

APG has the best wetting properties and reactivity. Among the quantum-chemically primed APG, AEO3 and NP-10 modifiers, the degree of interaction between APG and coal molecules was the strongest, and the two had the highest probability of electron leaps or transfers, old bond breakage and new bond formation.

-

(2)

1% APG synergistic acid solution has the best effect of wetting modification on experimental coal samples. The settling time of the experimental coal samples in 5 kinds of volume fractions (0.2%–1%) of APG and 6% HF composite solution were determined by the settling experiments, and it was found that the settling time of the coal samples in the 1% APG and 6% HF composite solution was the shortest.

-

(3)

The acid modifier can increase the hydrophilic functional group and free radical concentration of the experimental coal samples and improve their wettability. The hydrophilic functional group content of the modified experimental coal samples increased by 88.96%; the free radical concentration Ng increased from 4.08220 × 1018 spin/g to 4.19164 × 1018 spin/g.

-

(4)

There is a certain transformation relationship between free radicals (active sites) and functional groups in experimental coal samples under the action of acid modifier. After the acid modifier treated the experimental coal samples, a large number of active sites (i.e., free radicals) were formed after the hydrophobic functional groups were fractured and detached, and these active sites evolved into hydrophilic functional groups with the help of the acid modifier, and the existence of hydrophilic functional groups improved the wettability of the experimental coal samples by enhancing the surface polarity of the experimental coal samples.

-

(5)

The wettability of the experimental coal samples was increased after the acid modifier treatment. The wetting heat measurement showed that the wetting heat of the modified experimental coal samples increased by 14.86%, which proved that the acid modifier could have a chemical reaction with the coal, leading to the mutual transformation of the chemical structure (functional groups and free radicals) in the coal, and thus improving the wettability of the coal samples.

Data availability

The results from the present investigation are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable appeal.

References

Li, P. et al. Effect of wettability on adsorption and desorption of coalbed methane: A case study from low-rank coals in the southwestern ordos basin, China. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 12003–12015. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b01932 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Influence of wettability alteration on water-blocking effect and gas desorption of coal. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 180, 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.10.003 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Effects of acidification on the wettability modification of coal and adsorption characteristics of coalbed methane. Nat. Resour. Res. 32, 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-022-10141-9 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Effect of microwave-assisted acidification on the microstructure of coal: XRD, 1H-NMR, and SEM studies. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33, 919–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2023.03.009 (2023).

Wei, Z., Baiquan, L., Tong, L., Ting, L. & Wei, Y. Effect of acidification on microscopic properties and pore structure of coal. Fuel 343, 127834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127834 (2023).

Zhang, B., Deng, Z., Fu, X., Yu, K. & Zeng, F. An experimental study on the effects of acidization on coal permeability: Implications for the enhancement of coalbed methane production. Energy 280, 128145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.128145 (2023).

Zhao, D. & Liu, X. Investigation of the microscopic mechanism of H2O adsorption by low-rank coal slit pores through GCMC and MD simulations. Arab. J. Chem. 17, 105697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105697 (2024).

Wu, H., Yao, Y. & Du, X. Water adsorption characteristics of coal with different particle sizes: Experimental and modeling analyses. Nat. Resour. Res. 32, 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-023-10171-x (2023).

Hongchao, X. et al. The effect of SDS synergistic composite acidification onthechemical structure and wetting characteristics of coal. Powder Technol. 367, 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.03.056 (2020).

Guanhua, N. et al. The effect of anionic surfactant (SDS) on pore-fracture evolution of acidified coal and its significance for coalbed methane extraction. Adv. Powder Technol. 30, 940–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2019.02.008 (2019).

Hongchao, X. et al. The influence of surfactant on pore fractal characteristics of composite acidized coal. Fuel 253, 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.05.073 (2019).

Jingna, X. et al. The effect of adding surfactant to the treating acid on the chemical properties of an acid-treated coal. Powder Technol. 356, 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2019.08.039 (2019).

Hao, T., Jiang, S., Wang, L. & Jiang, W. Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation study of the effect of composite surfactants on wetting of coal dust. J. Mol. Liq. 409, 125552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125552 (2024).

Lin, Z., Chen, X., Xu, C., Wang, H. & Zhu, X. Effect of ionic liquid-surfactant compound solutions on the wettability and functional groups of coal. J. Mol. Liq. 401, 124650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2024.124650 (2024).

Wang, X., Yuan, S. & Jiang, B. Wetting process and adsorption mechanism of surfactant solutions on coal dust surface. J. Chem. 1–9, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9085310 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Synergistic adsorption mechanism of anionic and cationic surfactant mixtures on low-rank coal flotation. ACS Omega 5, 20630–20637. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c02948 (2020).

Xu, C. et al. Effects of chemical properties of coal dust on its wettability. Powder Technol. 318, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.05.028 (2017).

Zhou, Q., Qin, B., Ma, D. & Jiang, N. Novel technology for synergetic dust suppression using surfactant-magnetized water in underground coal mines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 109, 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2017.05.013 (2017).

Ji, H. et al. Insight into the influence of small organic molecules on the wettability of coal. Fuel 294, 120537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120537 (2021).

Li, L., Fan, H. & Hu, H. Distribution of hydroxyl group in coal structure: A theoretical investigation. Fuel 189, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.10.091 (2017).

Yu, Y., Liu, J., Wang, R., Zhou, J. & Cen, K. Effect of hydrothermal dewatering on the slurryability of brown coals. Energy Convers. Manag. 57, 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2011.11.016 (2012).

Zhen, K., Zheng, C., Li, C. & Zhang, H. Wettability and flotation modification of long flame coal with low-temperature pyrolysis. Fuel 227, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.04.073 (2018).

Zhang, J., Xu, B., Zhang, P., Cai, M. & Li, B. Effects of surface roughness on wettability and surface energy of coal. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1054896. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1054896 (2023).

Gosiewska, A., Drelich, J., Laskowski, J. S. & Pawlik, M. Mineral matter distribution on coal surface and its effect on coal wettability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 247, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcis.2001.8130 (2002).

Rane, K. S., Goual, L. & Zhang, B. Graphene quantum dots for the mobilization and solubilization of nonaqueous phase liquids in natural porous media. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 10691–10701. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.0c01937 (2020).

Gao, M. et al. Mechanism of micro-wetting of highly hydrophobic coal dust in underground mining and new wetting agent development. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2022.11.003 (2023).

Jiang, B. et al. Investigation on the effect of functional groups on the wettability of coal dust: Experiments and theoretical validation. Fuel 351, 128987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128987 (2023).

Gao, Y. et al. Study of the change laws of free radicals and functional groups during coal oxidation. ACS Omega 8, 7102–7110. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c08057 (2023).

Zhou, B. et al. The characterization of free radical reaction in coal low-temperature oxidation with different oxygen concentration. Fuel 262, 116524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116524 (2020).

Li, J., Li, Z., Yang, Y., Kong, B. & Wang, C. Laboratory study on the inhibitory effect of free radical scavenger on coal spontaneous combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 171, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2017.09.027 (2018).

He, J. Study on mechanical property degradation and permeability improvement response mechanism of coal under acidification. Guizhou University (2024).

Yuan, M. et al. Determining the effect of the non-ionic surfactant AEO9 on lignite adsorption and wetting via molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and experiment comparisons. Fuel 278, 118339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118339 (2020).

Xie, J., Du, H., Chen, S., Sun, X. & Xin, L. Chemical modification effect of compound solutions of surfactants with acetic acid on coal pores. ACS Omega 6, 35342–35354. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c04430 (2021).

Yuan, M. Study on microscopic mechanism of gas adsorption characteristics in coal under acidification. Guizhou University (2024).

Jin, H. et al. Molecular dynamics simulations and experimental study of the effects of an ionic surfactant on the wettability of low-rank coal. Fuel 320, 123951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123951 (2022).

Bai, X. et al. Study on the mechanism of the influence of surfactant alkyl chain length on the wettability of anthracite dust based on EDLVO theory and inverse gas chromatography. Fuel 353, 129187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129187 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Experimental and theoretical insight into the effect of a novel composite dispersant on the properties of coal pitch water slurry. Fuel 365, 131281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131281 (2024).

Meng, J. et al. Molecular simulation of the regulation mechanism of the hydrophilic structure of surfactant on the wettability of bituminous coal surface. J. Mol. Liq. 383, 122185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122185 (2023).

Feng, X. J. et al. Corrosion inhibition studies of 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives for N80 steel in a 1.0 M HCl solution: Experimental, computational chemistry, and quantitative structure-activity relationship studies. Langmuir 39, 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c02807 (2023).

Kannan, P., Karthikeyan, J., Murugan, P., Rao, T. S. & Rajendran, N. Corrosion inhibition effect of novel methyl benzimidazolium ionic liquid for carbon steel in HCl medium. J. Mol. Liq. 221, 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2016.04.130 (2016).

Cui, X. et al. Study on the structure and reactivity of COREX coal. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 113, 693–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-012-2782-8 (2012).

Wu, M., Qin, Y., Qin, Y., Xu, N. & Feng, L. The effect of temperature on molecular structure of medium-rank coal via Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Materials (Basel) 16, 6746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16206746 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Molecular dynamics simulation and experimental characterization of anionic surfactant: Influence on wettability of low-rank coal. Fuel 279, 118323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118323 (2020).

Zhou, G. et al. Effects of SDBS and BS-12 on functional groups/wettability of multicomponent acidified lignite. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 122908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122908 (2023).

Zhang, X., Lu, B., Qiao, L. & Ding, C. Study on the kinetics of chemical structure reaction in coal catalyzed by OH free radicals. Energy 285, 129553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.129553 (2023).

Hu, X. et al. The influence of methane on the development of free radical during low-temperature oxidation of coal in gob. Fuel 330, 125369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125369 (2022).

Jiang, X., Yang, S. & Zhou, B. Change characteristics of radicals in different stages of coal spontaneous combustion. Nat. Resour. Res. 32, 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-022-10130-y (2022).

Xu, Q. Oxygen adsorption capacity evolution of pre-oxidized coal and secondary oxidation characteristics of molecular active structure. China University of Mining & Technology (2021).

Tang, Z. Pore evolution during coal spontaneous combustion: Mechanism and its effect on multi-gas adsorption characteristics. China University of Mining & Technology (2020).

Xue, D. et al. Examination of characteristics of anti-oxidation compound inhibitor for preventing the spontaneous combustion of coal. Fuel 310, 122160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122160 (2022).

Ahamed, M. A. A., Perera, M. S. A., Matthai, S. K., Ranjith, P. G. & Dong-yin, L. Coal composition and structural variation with rank and its influence on the coal-moisture interactions under coal seam temperature conditions—A review article. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 180, 901–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.06.007 (2019).

Zhao, D., Liu, X. & Shen, Z. Effect of oxygen-containing functional groups on the wettability of coal through DFT and MD simulation. Arab. J. Chem. 16, 104606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104606 (2023).

Gui, X. et al. Intensification mechanism of oxidized coal flotation by using oxygen-containing collector α-furanacrylic acid. Powder Technol. 305, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2016.09.058 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Study on reaction sites of active structures in coal based on the ReaxFF reactive force field. ACS Omega 7, 45265–45276. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c05796 (2022).

Qu, Z. et al. A new insight into the role of coal adsorbed water in low-temperature oxidation: Enhanced·OH radical generation. Combust. Flame 208, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2019.06.017 (2019).

Li, J., Li, Z., Yang, Y. & Wang, C. Study on oxidation and gas release of active sites after low-temperature pyrolysis of coal. Fuel 233, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.039 (2018).

Wang, Y., Yang, W., Yang, W., Luo, L. & Lyu, J. Effect of AES anionic surfactant on the microstructure and wettability of coal. Energy 289, 130118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.130118 (2024).

Xia, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, R., Xing, Y. & Gui, X. Enhancement of the surface hydrophobicity of low-rank coal by adsorbing DTAB: An experimental and molecular dynamics simulation study. Fuel 239, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.10.156 (2019).

Li, B., Liu, S., Guo, J., Zhang, L. & Sun, X. Increase in wettability difference between organic and mineral matter to promote low-rank coal flotation by using ultrasonic treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 481, 454–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.03.142 (2019).

Liu, X., Liu, S., Fan, M., Guo, J. & Li, B. Decrease in hydrophilicity and moisture readsorption of Manglai lignite using lauryl polyoxyethylene ether: Effects of the HLB and coverage on functional groups and pores. Fuel Process. Technol. 174, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.02.010 (2018).

Hao, B., Fan, M., Li, Z. & Li, H. Study on the mechanism of adsorption and hydrophobic modification of glycerol monooleate/kerosene mixed collector on low-rank coal surface. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 674, 131960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.131960 (2023).

Liu, X., Liu, S., Fan, M. & Zhao, J. Calorimetric study of the wettability properties of low-rank coal in the presence of CTAB. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 130, 2025–2033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-017-6518-7 (2017).

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52164014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contributions of the individual authors to this article are as follows: ① Shuangxia Yi: Responsible for writing original drafts, visualization, software analysis, data management. ② Mei Yuan: Responsible for oversight, editing, review and access to funds. ③ Bobo Li: Responsible for methodological and formal analysis. ④ Xiaoyu Hu: Responsible for software analysis. ⑤ Heng Zhang: Responsible for software analysis. ⑥ Zongmian Hou: Responsible for investigation and analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, S., Yuan, M., Li, B. et al. Optimization of acid modifier and its effect on the wettability of anthracite coal. Sci Rep 15, 14189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96938-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96938-z