Abstract

Osteoporosis, a bone disease characterized by decreased bone mineral density (BMD) resulting in decreased mechanical strength and an increased fracture risk, remains poorly understood in children. Herein, we developed/validated a deep learning-based model to predict pediatric BMD using plain spine radiographs. Using a two-stage model, Yolov8 was applied for vertebral body detection to predict BMD values using a regression model based on ResNet-18, from which a low-BMD group was classified based on Z-scores of predicted BMD. Patients aged 10–20-years who underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and radiography within 6 months at our hospital were enrolled. Ultimately, 601 patients (mean age, 14 years 4 months [SD 2 years]; 276 males) were included. The model achieved robust performance in detecting vertebral bodies (average precision [AP] 50 = 0.97, AP [50:95] = 0.68) and predicting BMD, with significant correlation (r = 0.72), showing consistency across different vertebral segments and agreement (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.64). Moreover, it successfully classified low-BMD groups (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.85) with high sensitivity (0.76) and specificity (0.87). This deep-learning approach shows promise for BMD prediction and classification, with potential to enhance early detection and streamline bone health management in high-risk pediatric populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a bone disease characterized by a decrease in bone mineral density (BMD), which results in a decline in the mechanical strength of bones, ultimately leading to an increased risk of fracture1. As such, early detection and management of osteoporosis are critical for improving patients’ health and reducing their social cost2.

Many assessment tools have been developed to facilitate early osteoporosis detection including quantitative computed tomography (QCT), among which dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the most accurate. In adults, the World Health Organization recommends measuring bone density using DXA and defining osteoporosis as a T-score 2.53. Many national health organizations recommend measuring bone density annually. Various international organizations, including the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the International Society for Clinical Densitometry, have published clear guidelines regarding the age and interval of screening tests for osteoporosis. However, screening criteria for pediatric osteoporosis remain poorly established because pediatric osteoporosis has distinct characteristics from adult osteoporosis. For example, secondary causes, such as chronic diseases and medication, are more common in pediatric osteoporosis4, while the prevalence is much lower than in adults. Moreover, although DXA remains an excellent tool for measuring BMD in children, BMD values are significantly influenced by factors such as growth, height, and skeletal age5. Therefore, DXA is exclusively recommended for patients who may experience clear diagnostic benefits, including those with a history of bony fracture, and those with treatment implications through intervention6.

Despite the limitations in diagnosing pediatric osteoporosis, developing an early diagnostic process for high-risk groups and implementing early bone health management are crucial. During childhood and adolescence, the foundation for bone health is established, and peak bone mass attained during this period serves as a “bone bank” for the entire lifespan7. If bone health is not adequately managed during this critical period, the risk of fractures increases, particularly during growth spurts8. Additionally, given the recent rise in the incidence of pediatric osteoporosis9, it is increasingly important to identify comorbidities that contribute to bone fragility and address modifiable factors such as vitamin D deficiency10, low physical activity11,12, improper nutrition13, and medications14,15.

Therefore, various diagnostic methods have been explored as potential alternatives prior to measuring bone mineral density through DXA. Among these, the use of quantitative ultrasound to measure the bone mineral status of the peripheral skeleton has been recognized for its advantages, such as non-invasiveness and low radiation exposure, making it easier to apply in pediatric populations16. However, this modality has limited practical clinical applicability due to factors such as medical costs. Meanwhile, other previous studies attempted to develop BMD assessment tools using only simple radiographs which is one of the most commonly used imaging methods; however, no significant results have been obtained17,18. However, as artificial intelligence technologies develop, several deep learning-based screening models for osteoporosis with robust performance have been proposed19,20. However, to the best of our knowledge, these models only targeted adults, and no such model has been developed for children. This retrospective study was performed to test the hypothesis that a deep learning-based model using simple radiographs of the spine, which is a commonly imaged anatomical region for bone mineral density measurement, can efficiently predict bone mineral density even in pediatric populations. Through this study, we aimed to develop an automated deep learning-based model that can: (1) Accurately detect each lumbar vertebral segment in a simple radiograph, and (2) Predict the BMD values for each vertebral segment. To validate the proposed prediction model, we: (1) Analyzed the detection performance for each vertebral segment by comparing it with the manually labeled data; (2) Compared the predicted BMD values with the actual BMD values measured by DXA; and (3) Analyzed the discriminative performance of the low bone density group using age-specific Z-scores derived from the predicted BMD values.

Results

Data source

From November 1, 2005 to January 31, 2022, 1,057 images from 326 patients aged less than 20 years, with paired DXA and spine radiograph results were screened to create cohorts for analysis. Of these, 369 images from 54 patients were excluded due to inadequate image quality or incorrect positioning, the presence of a foreign body blocking vision, or radiographs taken in an orientation other than the anteroposterior view. Additionally, data from children under 10 years old, for which z scores could not be calculated due to a lack of population data, were excluded. Therefore, the final cohort included 601 images from 272 patients (Fig. 1).

Among the images included in the study, 276/601 were of male participants. The mean age of the participants was 14.4 years. The most common etiologies resulting in the need to perform DXA were neuromuscular disease (275 images), musculoskeletal disease (e.g., idiopathic juvenile scoliosis) (234 images), hematological and oncological disease (66 images), genetic disease (32 images), endocrine disease (25 image), and other etiologies, such as non-traumatic fracture without any history (39 image). The mean BMD and Z-score of the total lumbar spine were 0.710 and − 1.36, respectively. A total of 170 images had low bone densities for the age group, defined as a BMD Z-score below − 2.0. The characteristics of the study data are presented in Table 1.

Performance in lumbar segment detection

In total, 238 of the 240 vertebral bodies in the test set were detected through the model, of which 228 were classified into the correct detection group, demonstrating a performance above the IoU threshold. For the overall detection performance, the recall, precision, AP50, and AP [50:95] were measured as 0.98, 0.98, 0.97, and 0.68, respectively.

Performance at BMD prediction

Table 2 summarizes the model performance in terms of predicting BMD. For the overall data, a very high correlation between BMD and predicted BMD was observed (r = 0.72). The linear regression model revealed an excellent performance for predicted BMD compared to the measured BMD (R2 = 0.51; root mean square error [RMSE] = 0.13). Moreover, the regression model between the measured and predicted values was well calibrated (Fig. 2(a)). Furthermore, the model performance remained robust across all vertebral segments. Figure 2(b) presents the Bland–Altman plot between the measured and predicted BMD values. Most of the data (95.00%) had < ± 1.96 standard deviations, and non-significant bias was noted (mean Bland–Altman bias: − 0.04). Moreover, the predicted BMD value showed a favorable agreement with the measured BMD (ICC: 0.64, confidence interval [CI] 95% [0.64–0.80])

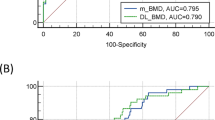

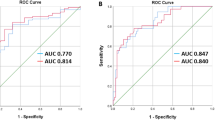

Performance in the classification of the low bone density group

Table 3 presents the discriminatory performance of the model for classifying patients with low bone density, based on a BMD Z-score of − 2.0. The classification performance of the overall data showed a high degree of discrimination in the low bone density group (AUROC: 0.85, Fig. 3(a), AUPRC: 0.83, Fig. 3(b)). The overall accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 0.83, 0.76, 0.87, 0.76, and 0.87, respectively. Furthermore, the model performance remained robust across sex strata.

Performance in the classification of the low bone density group using the predicted BMD values. (a) AUROC value and ROC curve of the classification model for the low bone mineral density group by age. (b) AUPRC value and PRC curve for the classification model of the low bone mineral density group by age. BMD bone mineral density, AUROC area under receiver operating characteristic curve, AUPRC area under the precision-recall curve.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to construct a model to predict BMD using only simple radiographs in children considered vulnerable to osteoporosis, as well as the first to classify low BMD by age group. Overall, the present model showed robust performance, not only in the detection of the ROI of body parts and BMD prediction, but also in the discrimination of patients with low BMD. Prior to this study, there have been various attempts to measure or predict BMD using diagnostic modalities other than DXA, and they have demonstrated clinical significance in terms of accuracy. However, the modalities used in previous research have been criticized for having limitations, such as poorer economic or spatial accessibility16,21 compared to DXA, or heightened concerns regarding radiation exposure22. Meanwhile, existing adult BMD prediction models have used simple radiographs of various anatomical regions, not only the traditional sites for measuring bone density such as the hip and spine20,23, but also the mandibular24 and calcaneus bone25, to classify and predict adult osteoporosis. However, these studies mostly focused on developing prediction models for the presence or absence of osteoporosis through learning, without extracting features related to the specific bone characteristics of the target area.

In contrast, this study not only predicted the BMD value of different regions of the vertebral body in the lumbar spine, which is a site particularly vulnerable to osteoporosis, but also demonstrated high discriminative performance when constructing a classification model based on these predictions. This study not only offers clinical utility for screening high-risk osteoporosis groups but also has the advantage of scalability as a bone health management model, including the prediction of bone strength and other related aspects.

Moreover, regarding the comparison between the existing BMD prediction model for adults and the present model, not only did those studies demonstrate high performance based on a large dataset, but they also proposed a new learning approach that decomposes data from the two gold standard assessment tools for bone mineral density measurement, QCT and DXA, to overcome the limitations of traditional direct regression methods26,27,28. On the other hand, developing models specialized for pediatrics poses several challenges. Due to the low prevalence of pediatric conditions, acquiring an adequate dataset is difficult, and modalities such as QCT are hard to use because radiation-exposure concerns. Despite using a significantly smaller dataset compared to the adult-based studies mentioned above, this study achieved performance levels comparable to those of the adult models (Supplementary Table 1).

In this study, to overcome the limitations of a small pediatric dataset and enhance the detection performance, our model further included special considerations unique to pediatric patients; for example, it considered that many of the underlying diseases that can cause low BMD are also associated with scoliosis29,30. We also specifically utilized a Yolov8-oriented bounding box (Yolov8-OBB) detection model that incorporated a function to tilt the bounding box according to the lateral abnormal curvature of the spine due to scoliosis, thereby enabling more accurate extraction of the vertebral body compared to the general Yolov8 model and resulting in a higher detection performance (recall: 0.88 vs. 0.98, precision: 0.88 vs. 0.98, AP50: 0.88 vs. 0.97 AP [50:95]: 0.437 vs. 0.682). However, because application of the OBB function did not achieve a clinically significant improvement in predictive and discriminative performance, even when analyzed using various networks (ResNet-18, ResNet-50, VGG-16, SqueezeNet, and EfficientNet) beyond the current backbone network (Table 4).

Additionally, to overcome data heterogeneity—such as significant variability in the body size of the pediatric dataset—we aimed to enhance predictive performance by unifying image sizes through a resizing preprocessing step before inputting them into the regression model. As a result, the overall predictive performance was robust; however, we observed an increasing trend in performance toward the lower lumbar region. This may be due to physiological factors such as the degree of weight-bearing, which generally result in higher BMD in the lower compared to the upper lumbar vertebrae31. Consequently, the reduced measurement variability may have facilitated the learning process. Furthermore, the smaller size of the upper compared to the lower lumbar vertebrae, as well as the possibility of being obscured by artifacts such as the rib cage, may have influenced the results. Meanwhile, when classifying the low bone density group using the Z-score calculated based on the predictive BMD value, we examined the nine misclassified test set cases and found that, except for one case, all misclassified samples were from female subjects. Various factors, including differences in bone size32 and vertebral morphology33 between sexes, may have influenced the results. Nevertheless, further analysis with a larger sample size is necessary to validate these findings.

This study has various important limitations that should be considered. First, the dataset used for model development was relatively small and composed only of patients diagnosed with medical conditions vulnerable to pediatric osteoporosis. To enhance the model’s accuracy and comprehensiveness, future studies should prospectively collect data from children without medical histories, in order to build a more extensive dataset. Second, this study developed a model based solely on the spine, which could miss osteoporotic features, as changes in vertebral geometry may not occur until BMD falls below a certain threshold. Future research should integrate both spine and femur data for a more comprehensive bone health management process. Third, due to the characteristics of the retrospective study design, follow-up based on fracture history could not be performed. Thus, we were only able to develop a classification model based on BMD values. In the future, a more pediatric-specific osteoporosis prediction model should be constructed after prospectively collecting information on fracture history, in addition to collecting simple radiographs and DXA results. Finally, the data used in this study were sourced exclusively from a single institution, restricting the model’s adaptability to broader demographic variations.

Through this study, we have developed a robust bone mineral density prediction model specifically designed for children at risk of bone loss. This research represents a significant advancement in the field, as it provides a crucial foundation for establishing a comprehensive bone health management process for pediatric patients susceptible to osteopenia, in the context of deep learning-based BMD prediction models that have predominantly focused on adults. Furthermore, future studies should focus on developing an integrated bone mineral density prediction and bone loss classification model, incorporating both spine and femur data, to further enhance the effectiveness and completeness of bone health management strategies.

Methods

Design and ethics

This diagnostic study was conducted at the Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the same institution (4-2022-0252). Severance Hospital IRB is organized and operates according to ICH-GCP and the applicable laws and regulations. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was waived as the current study was conducted retrospectively and utilized anonymized clinical data exclusively for analytical purposes. The consent waiver was approved by the IRB Committee 4 of the institution.

Data acquisition

This study involved the retrospective review of the data from both lumbar spine and DXA examinations conducted on patients diagnosed with medical conditions vulnerable to pediatric osteoporosis, who visited our clinic between November 1, 2005, and January 31, 2022 (Fig. 1). The patient inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 10–20 years, with available age-specific sample data on BMD; (2) underwent DXA and anteroposterior radiographs including the lumbar spine, such as lumbar spine X-ray, thoracolumbar spine X-ray, or whole-spine X-ray; and (3) an interval of less than 6 months between DXA and radiographs. We further excluded the data of patients for whom any one of the first to fourth lumbar vertebrae segments could not be identified for any reason, such as when a metal plate was used for scoliosis correction orthopedic surgery. Digital X-ray machines (Model: GR40CW, Samsung Electronics, Seoul, Korea; Model: GC85A, Samsung Electronics; Model: Discovery XR656, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA; Model: Thunder Platform, GE Healthcare; Model: INNOVISION, DK medical system, Seoul, Korea Model: DR 7500, KODAK, New York, NY, USA) and DXA machines (Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA) were operated by an experienced imaging technologist to acquire standard radiographs for the study population.

Model construction

The model constructed in this study comprised two stages. The first stage focused on predicting the BMD value of each vertebral segment by extracting the region of interest (ROI) in spine radiograph using a deep learning-based model. The second stage involved the derivation of the total BMD predicted value by averaging the predicted BMD values per image of the first to fourth lumbar vertebral segment, while the BMD z score for age was calculated using the rule-based model presented in previous studies34. All data were split randomly into three groups, comprising the training, validation, and test datasets, at a ratio of 8:1:1.

First stage: construction of the deep learning-based model

The deep learning-based model was constructed in two steps. The first step involved extracting the ROI. In the second step, a regression model was developed to evaluate the BMD value per vertebra. Deep convolutional neural networks were used throughout these two steps; the architecture of the models is presented in Figure 4(a). The first step involved detecting the first to fourth lumbar vertebrae segments as ROIs to calculate the BMD values from the lumbar DXA. For training and validation, Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files were used as input data, while the coordinates of all four corner edge points of each vertebra were manually labelled by two domain experts (JH and DW), with at least 5 years of experience in pediatric rehabilitation; these were used as ground truth data. The Yolov8 model35, which had an oriented bounding box function36, and was optimized to localize bounding box scaling and rotation angles, showed robust functionality in the extraction of ROIs from spinal X-ray images of children with varying vertebrate sizes and degrees of spinal deformity. This model was configured to detect up to four of the most confident ROIs (labelled L1, L2, L3, and L4) from top to bottom. In the second step of constructing the BMD prediction model, the coordinate data of the four vertebral segments used in the first step were also used as input data, while the BMD values from the DXA corresponding to each vertebral segment were used as the ground truth data. The backbone neural network used in the second step was ResNet-18, a widely used convolutional neural network. The training, validation, and testing steps shared the same training, validation, and test datasets. The training and validation datasets were used independently for their respective training processes. For the test dataset, the second step utilized the ROI derived from the first step as input data to perform consecutive BMD predictions.

Schematic diagram of the classification model applied in this study. (a) Process of the two-step BMD prediction. (b) Architecture of the entire model construction process. BMD bone mineral density. This image was created by the authors using Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2302; https://www.microsoft.com/powerpoint).

Second stage: construction of the classification model

This stage was conducted exclusively on the test dataset. Following the detection–prediction model pipeline, the BMD values for each vertebra were predicted. The overall predicted BMD value was calculated by averaging the BMD values across the L1–L4 lumbar segments, using a weighted averaging method that was inversely proportional to the area of the detection box. Finally, the predicted BMD Z-score for each image was determined based on the total predicted BMD value with reference to the age-specific mean and standard deviation BMD values for Korean children and adolescents (Figure 4(b))37.

Evaluation of model performance

The evaluation of all performance measures was conducted solely on the test datasets. To evaluate the performance of the vertebral body detection model in the first stage, we initially utilized the intersection over union (IoU), setting a threshold of 0.5 to distinguish between the correct and incorrect bounding boxes. In addition, two extra metrics, the average precision (AP) and the AP across different IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 (AP [50:95]), were employed to comprehensively assess the detection performance. For the performance measurement of the BMD prediction model in the second stage, Pearson’s correlation analysis was applied to analyze the association between the estimated and measured BMD values, whereas the Bland–Altman plot and two-way random-effects intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were applied to assess the agreement between them. The scale of Pearson’s correlation coefficient and ICC were assessed based on previous guidelines38,39. Additionally, the robustness and generalizability of the first stage model was evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation.

To construct the classification model in the second stage, the overall discriminative abilities for identifying the low bone density group were evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristics (AUROC) and area under the precision recall curve (AUPRC). Other parameters, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV), were also used. All analyses were performed using RStudio software (version 4.1.3; Posit PBC, Boston, MA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Glaser, D. L. & Kaplan, F. S. Osteoporosis. Definition and clinical presentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 22, 12s-16s (1997).

Lane, N. E. Epidemiology, etiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194, S3–11 (2006).

Kanis, J. A. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO study group. Osteoporos. Int. 4, 368–381 (1994).

Bishop, N. et al. Dual-energy X-ray aborptiometry assessment in children and adolescents with diseases that May affect the skeleton: the 2007 ISCD pediatric official positions. J. Clin. Densitom. 11, 29–42 (2008).

Boot, A. M., de Ridder, M. A., Pols, H. A., Krenning, E. P. & de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S. M. Bone mineral density in children and adolescents: relation to puberty, calcium intake, and physical activity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 57–62 (1997).

Gordon, C. M., Leonard, M. B. & Zemel, B. S. 2013 Pediatric Position Development Conference: executive summary and reflections. J. Clin. Densitom 17, 219–224 (2014).

Bachrach, L. K. Consensus and controversy regarding osteoporosis in the pediatric population. Endocr. Pract. 13, 513–520 (2007).

McCormack, S. E. et al. Association between linear growth and bone accrual in a diverse cohort of children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 171, e171769 (2017).

Gordon, R. J. et al. Osteoporosis and Bone Fragility in Children. In Endotext (eds. Feingold, K. R.) (MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000–2025, MDText.com, Inc., 2000).

Pettifor, J. M. & Prentice, A. The role of vitamin D in paediatric bone health. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 573–584 (2011).

Miller, K. K. et al. Determinants of skeletal loss and recovery in anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 2931–2937 (2006).

Chad, K. E., Bailey, D. A., McKay, H. A., Zello, G. A. & Snyder, R. E. The effect of a weight-bearing physical activity program on bone mineral content and estimated volumetric density in children with spastic cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. 135, 115–117 (1999).

Goulding, A., Grant, A. M. & Williams, S. M. Bone and body composition of children and adolescents with repeated forearm fractures. J. Bone Min. Res. 20, 2090–2096 (2005).

Valsamis, H. A., Arora, S. K., Labban, B. & McFarlane, S. I. Antiepileptic drugs and bone metabolism. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 3, 36 (2006).

Galindo-Zavala, R. et al. Expert panel consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of secondary osteoporosis in children. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 18, 20 (2020).

Baroncelli, G. I. Quantitative ultrasound methods to assess bone mineral status in children: technical characteristics, performance, and clinical application. Pediatr. Res. 63, 220–228 (2008).

Benhamou, C. L. et al. Fractal analysis of radiographic trabecular bone texture and bone mineral density: two complementary parameters related to osteoporotic fractures. J. Bone Min. Res. 16, 697–704 (2001).

Pothuaud, L. et al. Fractal analysis of trabecular bone texture on radiographs: discriminant value in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 8, 618–625 (1998).

Hsieh, C. I. et al. Automated bone mineral density prediction and fracture risk assessment using plain radiographs via deep learning. Nat. Commun. 12, 5472 (2021).

Jang, R. et al. Prediction of osteoporosis from simple hip radiography using deep learning algorithm. Sci. Rep. 11, 19997 (2021).

Galbusera, F. et al. Estimating lumbar bone mineral density from conventional MRI and radiographs with deep learning in spine patients. Eur. Spine J. 33, 4092–4103 (2024).

Kang, J. W., Park, C., Lee, D. E., Yoo, J. H. & Kim, M. Prediction of bone mineral density in CT using deep learning with explainability. Front. Physiol. 13, 1061911 (2022).

Yamamoto, N. et al. Deep learning for osteoporosis classification using hip radiographs and patient clinical covariates. Biomolecules 10, 1534 (2020).

Kavitha, M. S., Asano, A., Taguchi, A. & Heo, M. S. The combination of a histogram-based clustering algorithm and support vector machine for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Imaging Sci. Dentistry 43, 153 (2013).

Harrar, K., Hamami, L., Akkoul, S., Lespessailles, E. & Jennane, R. Osteoporosis assessment using Multilayer Perceptron neural networks. In 2012 3rd International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA), 217–221 (IEEE, 2012).

Gu, Y. et al. Bone mineral density Estimation from a plain X-ray image by learning decomposition into projections of bone-segmented computed tomography. Med. Image. Anal. 90, 102970 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Lumbar bone mineral density Estimation from chest X-Ray images: Anatomy-Aware attentive Multi-ROI modeling. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 42, 257–267 (2023).

Ho, C. S. et al. Application of deep learning neural network in predicting bone mineral density from plain X-ray radiography. Arch. Osteoporos. 16, 153 (2021).

Berven, S. & Bradford, D. S. Neuromuscular scoliosis: causes of deformity and principles for evaluation and management. Semin Neurol. 22, 167–178 (2002).

Li, X. F., Li, H., Liu, Z. D. & Dai, L. Y. Low bone mineral status in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 17, 1431–1440 (2008).

Ryan, P. J., Blake, G. M., Herd, R., Parker, J. & Fogelman, I. Distribution of bone mineral density in the lumbar spine in health and osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 4, 67–71 (1994).

Gilsanz, V. et al. Gender differences in vertebral body sizes in children and adolescents. Radiology 190, 673–677 (1994).

Janssen, M. M. A., Drevelle, X., Humbert, L., Skalli, W. & Castelein, R. M. Differences in male and female Spino-Pelvic alignment in asymptomatic young adults: A Three-Dimensional analysis using upright Low-Dose digital biplanar X-rays. Spine 34, E826–E832 (2009).

Choplin, R. H., Lenchik, L. & Wuertzer, S. A practical approach to interpretation of Dual-Energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for assessment of bone density. Curr. Radiol. Rep. 2, 48 (2014).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770-778 (2016).

Yu, X., Lin, M., Lu, J. & Ou, L. Oriented object detection in aerial images based on area ratio of parallelogram. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 16, 034510–034510 (2022).

Yi, K. H. et al. Reference values for bone mineral density according to age with body size adjustment in Korean children and adolescents. J. Bone Min. Metab. 32, 281–289 (2014).

Dancey, C. P. & Reidy, J. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology (Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2007).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing. This study was supported by a faculty research grant from the Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2022-0066). The funding source had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors declare no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H; Data curation, J.L and J.H.; Formal Analysis. J.H, J.C, and H.S; Investigation, J.H; Methodology, H.S, J.C, J.L, S.K and S.J.H; Project administration, J.H, and H.S; Resources, S.K , and J.H, Software, H.S, and S.J.H; Supervision, S.J.H and D.R; Validation, H.S; Visualization, J.H, and H.S; Writing – original draft, J.H, S.K, and H.S; Writing – review & editing, S.J.H, and D.R.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yonsei University College of Medicine (4-2022-0252), which further waived the requirement for informed consent, given the practical impossibility of obtaining informed consent from participants during the research process and the minimal risk posed to participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, J., Sung, H., Choi, Jo. et al. A prediction model of pediatric bone density from plain spine radiographs using deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 13039 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96949-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96949-w