Abstract

Knowing the geographical distribution of lineages and sublineages of each HPV type is beneficial for the epidemiological and evolutionary studies of this virus. However, no studies have analyzed the variants of HPV 33 and 35 in Iranian women. To investigate the sequence variation of HPV 33 and 35 E6 gene, 42 and 92 samples were analyzed using nested PCR and sequencing, respectively. Sublineage analysis of HPV 33 showed that most of the samples belonged to the A2 sublineage (85.8%) and the remaining were classified to the A1 sublineage. Four mutations at positions A132C, A213C, A364C, and A480T were detected, among which two mutations A213C and A364C led to amino acid changes corresponding to positions K35N and N86H of amino acid, respectively, in 85.8% of samples. For HPV 35, two sublineages A1 and A2 were found in studied samples with a prevalence of 84.8 and 15.2%, respectively. Seven nucleotide changes were observed at positions of C127G/T, A130C, A131C, C136T, G249T, A326G, and C341T. Three of these mutations including A130C, G249T, and C341T resulted in amino acid changes at positions of E7D, C47F, and R78W in 4.4%, 3.3%, and 9.8% of samples, respectively. Concerning HPV 33 or 35 distinct lineages by histology/cytology status, no statistically significant differences were observed. Our results indicated that sublineages A2 of HPV 33 and A1 of HPV 35 were dominant in Tehran, Iran. However, more studies with larger sample sizes from different histopathological stages of cervix in various geographical regions of Iran are necessary to evaluate the pathogenicity risk of HPV 33 and 35 (sub)lineages in Iranian women with cervical cancer in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most frequent viral sexually transmitted infection worldwide. Almost 80% of sexually active people who have not been vaccinated acquire the virus at some point in their lives. However, most HPV infections do not cause disease, and about 90% resolve spontaneously within 12–24 months post-infection, the remaining can persist and progress to cervical precancerous lesions or cancer1,2,3.

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women in the world as 662,301 new cases and 348,874 deaths have been reported in 2022. It is well-known that HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68 are responsible for the development of almost all invasive cervical cancer (ICC) cases; among which two types 16 and 18 accounts for 70% of ICC and seven types 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 detects in 20% of cases4,5,6. The eight most common HPV types in Iranian women with cervical cancer are as follows: HPV 16 (53%), 18 (15%), 31 (4%), 33 (3%), 45 (3%), 58 (3%), 35 (2%), and 52 (2%)7.

The classification of papillomaviruses is based on the DNA sequence of the L1 gene8. HPVs are clustered among five genera including alpha, beta, gamma, mu, and nu according to less than 60% identity. Within a given genus, the species and type are designated for those viruses that share 60–70% and 71–89% identity, respectively9,10. In each type, 1–10% and 0.5–1% identity through the genome are called lineage and sublineage, respectively. HPV 33 is clustered to alpha genus, species of 9 (alpha-9), and has three lineages of A, B, and C; among which A lineage consists of three distinctive sublineages A1, A2, and A3. HPV 35 is divided into alpha genus, species of 9 (alpha-9), and has two sublineages of A1 and A211.

Knowing the geographical spread of lineages and sublineages of each HPV type, is beneficial for the epidemiological and evolutionary studies of this virus. Several studies in Iran identified the (sub)lineages of HPV 16, 18, 31, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59. However, no studies have analyzed the variants of HPV 33 and 35 in Iranian women. To our knowledge, the sequence variability of the whole E6 gene of these two types was investigated to identify their circulating (sub)lineages in Tehran, Iran.

Material and methods

Study population

To investigate the sequence variations of HPV 33 and 35 E6 gene, a cross-sectional study was designed from 2021 to 2023 in Tehran. In total, 42 HPV 33 and 92 HPV 35-infected samples were analyzed to know their lineage/sublineages in this study. These 134 samples were obtained from the previous screening of one thousand liquid-based cervical samples (BD SurePathTM, Ireland) and four-hundred and sixty-five formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens. The liquid-based cervical samples were collected from several laboratories in Tehran that were infected with high-risk HPV types. FFPE samples were obtained from the archives of three hospitals in Tehran. Our research was conducted ethically by the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1402.336).

The sequence variations of HPV 33 and 35 E6 gene

Isolation of DNA from liquid-based cervical samples was done using High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA extraction from FFPE samples was carried out by phenol‐chloroform assay12.

The entire E6 gene of HPV 33 (nt 109–558) and HPV 35 (nt 110–559) was investigated using nested PCR with primer pairs shown in Table 1. The PCR reaction was done in a 50 μl reaction mixture, including a 2X PCR master mix (AMPLIQON, Ampliqon A/s, Denmark), 10 pmol of each primer, and 100–200 ng of DNA template. The PCR thermal cycling programs were included: an initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C, 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 50 s, and 72 °C for 50 s (first round) and 35 cycles of 95 °C for 25 s, 55 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 40 s (second round). A reaction mixture lacking template DNA was used as a negative control in every set of PCR runs. All PCR amplicons were sequenced bidirectional by the Sanger sequencing method with BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and a 3130 Genetic Analyzer Automated Sequencer as specified by Applied Biosystems manuals (Foster City, CA). The sequences were deposited in GenBank and are available with accession numbers PQ417275-PQ417408.

To characterize lineages and sublineages, all obtained sequences were aligned to reference sequences of HPV 33 and HPV 35. For HPV 33 the reference sequences were M12732 (A1), HQ537698 (A2), EU918766 (A3), HQ537705 (B), and KF436865 (C). The following reference sequences were HQ537720 (A1) and HQ537727 (A2) for HPV 3511. For both types, more sequences were obtained from GeneBank and used to draw a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree was made by Mega software version 11 using the maximum likelihood method and Kimura 2-parameter model. The reliability of the tree was calculated by measuring the bootstrap with 1000 replicates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculation was done using the Fisher exact test (Epi Info 7, Statistical Analysis System Software). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In total 134 uterine cervical samples (42 and 92 positive samples of HPV 33 and 35, respectively) were investigated in this study.

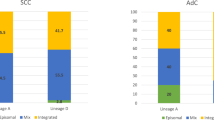

The full E6 sequence (nt 109–558) of 42 HPV 33-positive samples was aligned as opposed to the HPV 33 reference sequence (GeneBank accession number M12732). As shown in Fig. 1, all samples were classified to A lineage. Sublineage analysis showed that most of the studied samples belonged to A2 sublineages (85.8%) and the remaining were classified to A1 sublineage.

Nucleotide changes were found in 36 samples (85.8%), while no mutations were detected in 14.2% (Table 2). Four mutations at positions of A132C, A213C, A364C, and A480T were detected in 66.7%, 85.7%. 85.7%, and 19.1% of our samples, respectively. Mutations A213C and A364C led to amino acid changes corresponding to positions K35N and N86H of amino acid, respectively. Amino acid changes occurred in 36 samples (85.8%). In the studied groups, amino acid changes were detected in 90.9 and 80% of normal and premalignant/malignant groups, respectively. In this study, three nucleotide substitution patterns were found as follows: no changes (14.2%); A213C/A364C/A480T (19.1%); and A132C/A213C/A364C (66.7%). Two amino acid substitution patterns including no changes and K35N/N86H were detected in 14.2 and 85.8% of samples, respectively. No statistically significant differences were found between sublineages of HPV 33 and histology/cytology status (P = 0.57; OR (95% CI) 2.5 (0.4–15.4)) (Table 3).

As shown in Table 4, ninety-two complete E6 sequences (nt 110–559) of HPV 35-infected samples were compared to the HPV 35 reference sequence (GeneBank accession number HQ537720). Two sublineages, A1 and A2, with a prevalence of 84.8% and 15.2%, respectively, were found in studied samples (Fig. 2). In the entire E6 gene, seven nucleotide changes were observed at positions of C127G/T, A130C, A131C, C136T, G249T, A326G, and C341T. Three of these mutations, including A130C, G249T, and C341T, resulted in amino acid changes at positions of E7D, C47F, and R78W (Table 3). The frequency of amino acid changes was 9.8% for R78W, 4.4% for E7D, and 3.3% for C47F in our samples. In other words, no amino acid substitutions occurred in most of the studied samples (83.6%).

As shown in Table 4, ten nucleotide substitution patterns including no changes; C127G; A130C/A131C; A131C; G249T; C341T; C127T/C136T; C127T/C136T/C341T; C127T/A130C/C136T/C341T; and C127T/C136T/A326G/C341T were observed. Five patterns of amino acid changes occurred as follows: no changes (83.6%); E7D (3.3%); C47F (3.3%); R78W (8.7%); and R78W/E7D (1.1%).

Although the prevalence of sublineage A1 was higher in premalignant/ICC (91.7%) than normal (83.7%) samples, no statistically significant differences were observed in this regard (P = 0.84; OR (95% CI): 0.47 (0.05–3.9)) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study revealed that all HPV 33-infected samples belonged to the A lineage, the A2 sublineage was dominant (85.8%), and the remaining were classified to the A1 sublineage (14.2%). The A2 sublineage is reported to be more prevalent in Europe and Asia than in other parts of the world. This sublineage is found among 47.2 and 51.8% of European and Asian women, respectively13. In consistence with our findings, the A2 sublineage (60%) was more prevalent than the A1 sublineage (40%) in Hungarian women14. The data of ICC samples from India and South America showed that although A2 sublineage was more common (85.7%) than A1 (14.3%) in India, A1 sublineage was more frequent (81.8%) than A2 (18.2%) in South America15. The results of one study from the USA showed that A1 sublineage is dominant (69.7%), followed by B (19.7%) and A2 (10.6%) (sub)lineages16. In Japan, the frequency of (sub)lineages was as follows: A1 (70%), A2 (15%), A3 (5%), and B (10%)17. In China, two sublineages A1 and A3 were detected in 92.1% and 7.9% of cervical samples, respectively18. In Africa, B lineage is dominant (63%) followed by A1 (32.6%) and C (4.4%) (sub)lineages13.

Most of our samples detected two amino acid changes at positions K35N and N86H. Both alterations were not found at important positions linked to known E6 biological functions. However, a previous study revealed that amino acid changes at positions of I73L, V83L, K93N, and A138V of E6 had a higher ability to degrade P53 and MAGI-3 than the prototype13.

In the present study, no statistical differences were found between distinct sublineages of HPV 33 and histology/cytology status. Accordance to our data no associations were found in this regard on samples from Canada and Brazil which sublineage A1 was found to be more common in both normal (70.3%) and high-grade intraepithelial lesions (66.7%) than (sub)lineages A2 or B19. A study from China showed that the A1 sublineage was more frequent than the A3 sublineage among both normal and CIN I-III groups20. However, several studies reported that sublineage A1 has increased oncogenic potential than sublineage A213,21. Indeed, it is indicated that HPV 33 LCR variants of sublineage A2 have reduced transcriptional activities compared to sublineage A114. Our finding that not observed statistically significant differences can be due to the low sample size in both groups as inferred from Table 2, sublineage A1 was more common in the CIN I-III/ICC group than the normal group.

It is indicated that HPV 33 (sub)lineages A2, A3, B, and C than A1 displayed a reduced sensitivity to neutralization (2–fourfold) by nonavalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil®9) antibodies. This finding suggests that the natural variation in L1 alters capsid antigenicity and consequently affects neutralization by a range of antibody specificities22,23.

Two sublineages A1 and A2 of HPV 35 were detected with a frequency of 84.8% and 15.2% in the studied samples, respectively. Compatible with our results, studies have shown that sublineage A1 is dominant in America as the A1 and A2 sublineages were detected in 85.8 and 14.2% of samples, respectively21. In Brazil, sublineage A1 is also reported in 83.3% of cervical samples and the remaining belonged to sublineage A2 (16.7%)24. The whole-genome analysis results in Zimbabwe revealed that sublineages A1 and A2 were found in 75% and 25% of samples, respectively25. However, sublineage A2 (69.1%) is more common than A1 (30.9%) in Costa Rica26. A comprehensive study from different parts of the world showed that sublineage A1 was more common than A2 in non-African world districts for premalignant and malignant cervical samples. On the contrary, sublineage A2 was more frequent than A1 in African women. The B lineage was also detected in Bhutan and India27.

While the frequency of sublineage A1 was higher in premalignant/ICC than in normal groups, no statistically significant differences were observed. Previous studies have shown discrepancies in this regard. It is reported that sublineage A1 than A2 had long persistency and increased risk of CIN III in women from Costa Rica28. However, a study from America has shown that the chance of progression toward CIN II-III for sublineages A1 and A2 was not different21.

It is suggested that the genetic differences in host, particularly HLA molecules, can play a significant role in the population-based distribution of HPVs variants29. Previous studied determining lineage/sublineages of several high-risk HPVs in Iran were shown that distinctive lineage/sublineages are common as follow: lineage D of HPV 16, sublineage A4 of HPV 18, lineage A of HPV 31, sublineage A1 of HPV 39, lineage B of HPV 45, lineage B of HPV 5630,31,32,33,34.

The main limitation of this study was low sample size in our studied groups. Also, all samples were collected from Tehran and no other provinces of Iran were included. It is highly recommended that in future studies samples obtain from different parts of Iran.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that sublineages A2 of HPV 33 and A1 of HPV 35 were dominant in Tehran, Iran. However, more studies with larger sample sizes from different histopathological stages of cervix in various geographical regions of Iran are necessary to evaluate the pathogenicity risk of HPV 33 and 35 (sub)lineages in Iranian women with cervical cancer in the future. Also, the investigation of HLA molecules in Iranian women with cervical cancer highly recommended to be considered in the context of HPV 33 and 35 variants in future studies.

Data availability

The sequences were deposited in GenBank and are available with accession numbers PQ417275-PQ417408 with the following links: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ417275-PQ417408.

Abbreviations

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- ICC:

-

Invasive Cervical Cancer

References

de Sanjosé, S., Brotons, M. & Pavón, M. A. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 47, 2–13 (2018).

Okunade, K. S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 40(5), 602–608 (2020).

Doorbar, J. et al. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev. Med. Virol. 25, 2–23 (2015).

Munoz, N. et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N. Engl. J Med 348(6), 518–527 (2003).

Bouvard, V. et al. A review of human carcinogens–Part B: Biological agents. Lancet Oncol 10(4), 321–322 (2009).

Doorbar, J. et al. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine 30, F55–F70 (2012).

Salavatiha, Z. et al. A meta-analysis of human papillomavirus prevalence and types among Iranian women with normal cervical cytology, premalignant lesions, and cervical cancer. J. Med. Virol. 93(8), 4647–4658 (2021).

Van Doorslaer, K. Revisiting papillomavirus taxonomy: A proposal for updating the current classification in line with evolutionary evidence. Viruses 14(10), 2308 (2022).

Bernard, H. U. et al. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401(1), 70–79 (2010).

de Villiers, E.-M. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 445(1), 2–10 (2013).

Burk, R. D., Harari, A. & Chen, Z. Human papillomavirus genome variants. Virology 445(1–2), 232–243 (2013).

Jalilvand, S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 variants in Kaposi’s sarcoma from Iranian patients. Virus Res. 163(2), 644–649 (2012).

Chen, A. A. et al. Human papillomavirus 33 worldwide genetic variation and associated risk of cervical cancer. Virology 448, 356–362 (2014).

Gyöngyösi, E. et al. Transcriptional activity of the long control region in human papillomavirus type 33 intratype variants. Virol. J. 20(1), 152 (2023).

Godínez, J. et al. Differential presence of Papillomavirus variants in cervical cancer: An analysis for HPV33, HPV45 and HPV58. Infect. Genet. Evol. 13, 96–104 (2013).

Xi, L. F. et al. Lineages of oncogenic human papillomavirus types other than type 16 and 18 and risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju270 (2014).

Xin, C. Y. et al. Analysis of E6 variants of human papillomavirus type 33, 52 and 58 in Japanese women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia/cervical cancer in relation to their oncogenic potential. Cancer Lett. 170(1), 19–24 (2001).

Chen, Z. et al. E6 and E7 gene polymorphisms in human papillomavirus types-58 and 33 identified in Southwest China. PLoS ONE 12(1), e0171140 (2017).

Khouadri, S. et al. Human papillomavirus type 33 polymorphisms and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the uterine cervix. J Infect Dis 194(7), 886–894 (2006).

Yan, Z.-Y. et al. Cervical carcinogenesis risk association of HPV33 E6 and E7 genetic variations in Taizhou, Southeast China. Virol. J. 20(1), 156 (2023).

Xi, L. F. et al. Lineages of oncogenic human papillomavirus types other than type 16 and 18 and risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Nat. Cancer Inst. 106(10), dju270 (2014).

Godi, A. et al. Sensitivity of human papillomavirus (HPV) lineage and sublineage variant pseudoviruses to neutralization by nonavalent vaccine antibodies. J Infect Dis 220(12), 1940–1945 (2019).

Godi, A. et al. Comprehensive assessment of the antigenic impact of human papillomavirus lineage variation on recognition by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies raised against lineage a major capsid proteins of vaccine-related genotypes. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01236-20 (2020).

Basto, D. L. et al. Genetic diversity of human papillomavirus types 35, 45 and 58 in cervical cancer in Brazil. Arch. Virol. 162(9), 2855–2860 (2017).

Fitzpatrick, M. B. et al. Whole-genome analysis of cervical human papillomavirus type 35 from rural zimbabwean women. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 7001 (2020).

Schiffman, M. et al. A population-based prospective study of carcinogenic human papillomavirus variant lineages, viral persistence, and cervical neoplasiaHPV variants and cervical neoplasia. Can. Res. 70(8), 3159–3169 (2010).

Pinheiro, M. et al. Association of HPV35 with cervical carcinogenesis among women of African ancestry: Evidence of viral-host interaction with implications for disease intervention. Int. J. Cancer 147(10), 2677–2686 (2020).

Schiffman, M. et al. A population-based prospective study of carcinogenic human papillomavirus variant lineages, viral persistence, and cervical neoplasia. Can. Res. 70(8), 3159–3169 (2010).

Kohaar, I. et al. Association between human leukocyte antigen class II alleles and human papillomavirus-mediated cervical cancer in Indian women. Hum. Immunol. 70(4), 222–229 (2009).

Hosseini, N. et al. Lineage analysis of human papillomavirus type 39 in cervical samples of Iranian women. Virol. J. 18(1), 152 (2021).

Hosseini, N. et al. Lineage analysis of human papillomavirus types 31 and 45 in cervical samples of Iranian women. J. Med. Virol. 93(6), 3857–3864 (2021).

Jalali-Alhosseini, P. et al. Lineage and sublineage analysis of human papillomavirus type 56 in cervical samples of Iranian women. J. Med. Virol. 93(11), 6412–6417 (2021).

Salavatiha, Z. et al. Lineage analysis of human papillomavirus type 18 based on E6 region in cervical samples of Iranian women. J. Med. Virol. 92(12), 3815–3820. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26283 (2020).

Vaezi, T. et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 lineage analysis based on E6 region in cervical samples of Iranian women. Infect. Genet. Evol. 55, 26–30 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study has been funded and supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Grant no. 68275 and 71552.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ and ZS designed and directed the project; ME processed the pathological data; MS and ST carried out experimental data; ME performed the analysis; SJ and ZS involved in drafting the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our research was conducted ethically by the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects and approved by the local ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1402.336).

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shabanpour, M., Taherkhani, S., Shoja, Z. et al. Lineage analysis of human papillomavirus types 33 and 35 based on E6 gene in cervical samples from Tehran, Iran. Sci Rep 15, 13736 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97080-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97080-6