Abstract

The relationship between Klotho and epilepsy is poorly understood. This study aimed to investigate the association between serum Klotho levels and epilepsy. A total of 99,966 individuals who participated in the NHANES from the 2013 to 2016 were initially included. After excluding participants with missing data on serum Klotho concentration (57,286), epilepsy (6) and relevant covariates (6,096), the final sample consisted of 36,578 participants, with a mean age of 59 years. Weighted multivariable logistic regression analyses showed that high serum Klotho levels were negatively associated with the prevalence of epilepsy, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.74 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.64 to 0.86; P < 0.001. The Restricted Cubic Spline analyses (RCS) model showed a non-linear relationship between the serum Klotho levels and epilepsy. Subgroup analysis showed that serum Klotho levels were negatively correlated with epilepsy prevalence in individuals under 65 years of age and in males. Our study suggests that serum Klotho levels were associated with the prevalence of epilepsy. Further large-scale prospective studies and randomized trials are warranted to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic brain disorder that most often begins in childhood or in older adults1,2. Epilepsy can be caused by any neurological insult that disturbs the excitation and inhibition of a group of neurons3. The prevalence of Epilepsy is highest in people over 65 years of age, accounting for nearly 25% of new-onset epilepsy cases4. People who developed epilepsy before the age of 18 years live longer, while the older population with epilepsy has a high prevalence of comorbidities, such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia5,6,7,8.

Klotho is a transmembrane protein that encoded by Klotho gene, which is an “aging-suppressor” gene9. After proteolytic cleavage, a soluble form of Klotho protein (S-Klotho) is produced and could be detected in serum, which decrease with age10. Klotho has a wide range of biological functions, such as anti-neuroinflammation and the regulation of oxidative stress9,11. In the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) rat model of Parkinson’s disease, exogenous Klotho alleviated nigrostriatal dopaminergic injury by reducing astrogliosis, apoptosis, and oxidative stress12. Zhao et al. reported that Klotho reduced brain amyloid-β (Aβ) levels and protected against cognitive deficits in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 (APP/PS1) mice13. Recent research has linked the Klotho protein to cognitive function; injecting the protein into aged rhesus monkeys can improve their working memory and the ability to perform certain tasks14. Researches have provided evidence that Klotho has protective effects in a number of neurodegenerative diseases15,16,17,18. However, it is not very clear how Klotho is specifically related to epilepsy.

An observational study found that Klotho gene expression was significantly downregulated in patients with epilepsy19. Studies have also found that Klotho alleviates cognitive deficits in animal model of epilepsy. In a chronic epilepsy mouse model, Klotho could attenuate neuronal cell death and exert a neuroprotective effect20. In a temporal lobe epilepsy rat model, Klotho plays a neuroprotective role by preventing ferroptosis and iron overload, increasing the levels of glutathione peroxidase and glutathione in the hippocampus, and suppressing the levels of reactive oxygen species21. Klotho can also reduce neuroinflammation and improve cognitive deficits in epileptic rats22. However, there is currently a lack of clinical studies on the relationship between Klotho and epilepsy.

Therefore, we included data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), covering the years 2013–2016, to conduct a comprehensive investigation of serum Klotho levels and the prevalence of epilepsy in US adults, and the possible curvilinear association between them.

Materials and methods

Study design

NHANES is a comprehensive, ongoing research initiative that began in the early 1960s with the primary goal of assessing the health and nutrition status of the U.S. population across age groups. This program used a tiered, sequential sampling framework to periodically collect, every 2 years, a range of health-related data from a sample of the American population that was reflective of the nation as a whole. The information collected through NHANES includes a variety of domains, such as socioeconomic demographics, dietary habits, clinical examination findings, laboratory measurements, survey responses, and certain data restricted from general access. The NHANES protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, ensuring that all respondents gave their documented, informed consent to participate in the survey.

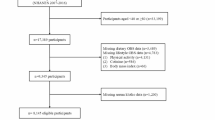

For the purposes of this investigation, we used data from two cycles (2013–2014 and 2015–2016) that included details on epilepsy and Klotho. The initial sample included 99,966 individuals who participated in NHANES during the years 2013–2016. Our focus was on the age range of 60–79 years, with available serum Klotho concentration data for 57,286 individuals. After excluding participants with missing epilepsy information (6) and those missing additional relevant variables (6096), the final number of participants for this study was 36,578. The Fig. 1 outlines the procedural steps used to select and filter participants for the study.

Serum Klotho concentrations

The method for measuring Klotho concentrations in the NHANES database utilized a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit23. Samples were stored at − 80 °C prior to analysis and provided to technicians in predetermined batches for daily analysis. Samples were analyzed in duplicate and the average of the two values is used to calculate the final measurement. In addition, quality control samples with low and high Klotho concentrations were also analyzed on each ELISA plate to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the analysis.

Assessment of epilepsy

The NHANES questionnaire data did not directly assess epileptic seizure events. Instead, information on epilepsy was collected through face-to-face interviews between investigators and participants. We used the same method as in previous studies to define epilepsy24,25,26. Participants were classified based on whether they reported taking at least one medication specifically for “epilepsy and recurrent seizures” (International Classification of Diseases [ICD] code G40). All participants reported the names of the medications prescribed by health professionals and main reasons for taking each antiepileptic drug. If a participant used at least one antiepileptic drug or reported recurrent epileptic seizures, they were defined as having an epileptic seizure event. Although this identification method has its limitations, it remains the most effective way to distinguish whether participants in this study have epilepsy.

Covariate information

Concomitant variables included age, sex, race, poverty income ratio (PIR), education, marital status, body mass index (BMI), smoke status, alcohol drinker and physical activity. When examining the association between serum Klotho levels and the prevalence of epilepsy, the above variables were considered potential confounders. Age and BMI were treated as continuous variables, sex and smoking status use as binary variables, and the rest as categorical variables. The assessment of all covariates was summarized in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with the NHANES analytical protocols, each analysis must incorporate sampling weights and complex sampling methods to ensure the accuracy and reliability of statistical inferences. For continuous data, the results were presented as weighted averages with their corresponding standard deviations, and for binary data, they are shown as rates (weighted percentages). Individuals were categorized into tertiles based on their serum Klotho levels, with the lowest tertile serving as the comparison group (T1). The association between serum Klotho levels and the prevalence of epilepsy was examined using multiple logistic regression models, either without adjustments or after adjustment for all potential confounders. Trend tests (P value for trend) were performed by entering the Klotho (quartile-categorical) as continuous variable, and rerunning the corresponding regression models27. The dose–response relationship between serum Klotho levels and the prevalence of epilepsy was modeled using restricted cubic splines (RCS). Statistical calculations were performed using R software, version 4.2.1. A P value of less than 0.05 from a two-tailed test was considered statistically important.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

According to the serum Klotho concentration tertiles, the general characteristics of the participants were shown in Table 2. A total of 36,578 participants had a mean age of 59 years, 44.9% were male and 4.3% had epilepsy. There were no significant differences in age, sex, PIR, education level, marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol drinker and physical activity among the tertiles of serum Klotho. Significant differences were observed in race (P < 0.001) and epilepsy (P = 0.003) between serum Klotho tertiles.

Relationship between serum Klotho concentrations and epilepsy

Three multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between serum Klotho and epilepsy (Table 3). Compared with the reference in the T1 group, the associations between serum Klotho concentration and epilepsy in the T2 group were not statistically significant in either the unadjusted model (Model 1: P = 0.002) or the adjusted model (Model 2: P < 0.001; Model 3: P < 0.001). However, the T3 group showed a significant negative relationship between serum Klotho concentration and epilepsy in all models (P < 0.001). For the continuous variable, the association between serum Klotho concentration and epilepsy was also significant in the unadjusted model (Model 1: P for trend = 0.002) and in the adjusted model (Model 2: P for trend < 0.001; Model 3: P for trend < 0.001).

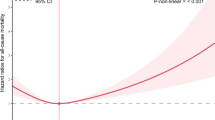

Nonlinear relationship between Klotho concentrations and epilepsy

We used RCS to analyze the correlation between serum Klotho concentration and epilepsy. A nonlinear relationship was observed between them before (Model 1: P < 0.001) or after adjusting for covariates (Model 2: P < 0.001; Model 3: P < 0.001). The OR for epilepsy gradually decreased when the serum Klotho concentration reached 770.2362 pg/mL, after which it began to decrease slightly and reached saturation. Before or after adjustment for all covariates, the OR of epilepsy gradually increased before the serum Klotho concentration reached the inflection point (Model 1: 616.827 pg/mL; Model 2: 770.236 pg/mL), after which it began to decrease and became stable (Fig. 2A,B). In the model 2, after adjustment for age and sex, the OR for epilepsy continued to decrease until it stabilized (Fig. 2C).

The odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for epilepsy determined by serum Klotho levels. The red solid line represents the fitted regression line, while the OR is indicated by the horizontal gray dashed line. Additionally, the 95% CI is illustrated as a shaded region surrounding the OR.

Relationship between serum Klotho concentrations and epilepsy in subgroups

We investigated the relationship between serum Klotho levels and epilepsy in different subgroups. In the population under 65 years of age (Table 4) or among males (Table 5), the T3 group exhibited a negative correlation between serum Klotho levels and the prevalence of epilepsy compared to the T1 group in the unadjusted (Model 1: P < 0.001) and adjusted model (Model 2: P < 0.001; Model 3: P < 0.001). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of epilepsy associated with serum Klotho concentration in the population aged 65 years and older or in females.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study was the first to found that higher serum Klotho levels were associated with a lower prevalence of epilepsy. And subgroup analysis show that serum Klotho was reduced in individuals less than 65 years of age and in men with epilepsy.

Studies have shown that the prevalence of epilepsy is highest in the population over 65 years of age, with a prevalence of epilepsy is as high as 5.7%28,29. Therefore, we conducted an age subgroup analysis using 65 years as the cutoff, and the results indicated that there is a negative correlation between serum Klotho levels and epilepsy in the population under 65 years of age, while there was no correlation in the population over 65 years of age. Previous studies have shown that there are gender differences in the incidence of epilepsy30,31. It has been found that men have a higher lifetime risk of developing epilepsy, possibly due to their occupations and exposure to risk factors such as alcohol use and head trauma32. Furthermore, the lower consultation rate among women is often attributed to the stigma and the lower economic status of families in rural areas33. Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis by Sex, and the results showed that there was a negative correlation between serum Klotho and epilepsy in the male population, while there was no statistically significant difference in the female population.

Klotho has shown potential in the treatment of a variety of age-related diseases, including renal, neurodegenerative, muscle and osteoarticular diseases34,35,36,37,38,39. The therapeutic effects of Klotho are currently being investigated in several clinical studies. A study published in Nature Aging examined the effects of injecting Klotho protein into aged rhesus monkeys on their working memory and task performance. Although the specific mechanisms are not yet clear, this finding may provide a new treatment method for neurodegenerative diseases14. In addition, another study demonstrated in animal and human studies that using the anti-aging drug combination Dasatinib + Quercetin (“D + Q” regimen) could increaseα-Klotho protein in the body, which may help protect the elderly from the effects of aging and a variety of diseases40. Research on Klotho protein and epilepsy is gradually unfolding, and some animal experiments currently show that Klotho may play a beneficial role in the treatment of epilepsy, but specific clinical applications require more research to verify.

Our study has several strengths. For the first time, we identified a negative and nonlinear relationship between serum Klotho levels and epilepsy in a large clinical sample. Secondly, through subgroup analysis, we found that high serum Klotho levels were associated with epilepsy in individuals younger than 65 years and in males. In addition, due to the impact of confounding factors in observational studies, we used strict control strategies in this study to minimize their impact. These results suggested that serum Klotho levels were associated with the prevalence of epilepsy.

However, this study also has some limitations. Firstly, this study is an observational cross-sectional study, which could only draw conclusions of association rather than causality. In addition, the definition of epilepsy was based on the use of antiepileptic drugs rather than on the standard criteria for the clinical diagnosis of epilepsy. Furthermore, the number of epilepsy patients included in this study is limited, and larger sample studies are needed in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, higher serum Klotho levels were associated with a lower prevalence of epilepsy. Subgroup analysis showed reduced serum Klotho in subjects younger than 65 years and in males with epilepsy. Future prospective studies and clinical trials are needed to confirm our findings.

Data availability

Data are available on the NHANES website (www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

References

Sen, A., Jette, N., Husain, M. & Sander, J. W. Epilepsy in older people. Lancet (London, England) 395(10225), 735–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)33064-8 (2020).

Thijs, R. D., Surges, R., O’Brien, T. J. & Sander, J. W. Epilepsy in adults. Lancet (London, England) 393(10172), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32596-0 (2019).

Devinsky, O. et al. Epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 18024. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.24 (2018).

Ferlazzo, E., Sueri, C., Gasparini, S. & Aguglia, U. Challenges in the pharmacological management of epilepsy and its causes in the elderly. Pharmacol. Res. 106, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.013 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy: An increasingly recognized comorbidity. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 940515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.940515 (2022).

Tsai, Z. R. et al. Late-onset epilepsy and subsequent increased risk of dementia. Aging (Albany NY) 13(3), 3573–3587. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202299 (2021).

Gold, P. W., Licinio, J. & Pavlatou, M. G. Pathological parainflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress in depression: Potential translational targets through the CNS insulin, klotho and PPAR-γ systems. Mol. Psychiatry 18(2), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.167 (2013).

Pavlatou, M. G., Remaley, A. T. & Gold, P. W. Klotho: A humeral mediator in CSF and plasma that influences longevity and susceptibility to multiple complex disorders, including depression. Transl. Psychiatry 6(8), e876. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.135 (2016).

Xu, Y. & Sun, Z. Molecular basis of Klotho: From gene to function in aging. Endocr. Rev. 36(2), 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2013-1079 (2015).

Kuro, O. M. The Klotho proteins in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-018-0078-3 (2019).

Bian, A., Neyra, J. A., Zhan, M. & Hu, M. C. Klotho, stem cells, and aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 10, 1233–1243. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S84978 (2015).

Baluchnejadmojarad, T. et al. The anti-aging protein klotho alleviates injury of nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway in 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of Parkinson’s disease: Involvement of PKA/CaMKII/CREB signaling. Exp. Gerontol. 100, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.10.023 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. Klotho overexpression improves amyloid-β clearance and cognition in the APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 19(10), e13239. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13239 (2020).

Castner, S. A. et al. Longevity factor klotho enhances cognition in aged nonhuman primates. Nat. Aging 3(8), 931–937. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00441-x (2023).

Paroni, G. et al. Klotho at the edge of Alzheimer’s disease and senile depression. Mol. Neurobiol. 56(3), 1908–1920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1200-z (2019).

Landry, T. et al. Central α-klotho suppresses NPY/AgRP neuron activity and regulates metabolism in mice. Diabetes 69(7), 1368–1381. https://doi.org/10.2337/db19-0941 (2020).

Scazzone, C. et al. Klotho and vitamin D in multiple sclerosis: An Italian study. Arch. Med. Sci. 16(4), 842–847. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2019.86969 (2020).

Dubal, D. B. et al. Life extension factor klotho prevents mortality and enhances cognition in hAPP transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 35(6), 2358–2371. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5791-12.2015 (2015).

Teocchi, M. A., Ferreira, A., da Luz de Oliveira, E. P., Tedeschi, H. & D’Souza-Li, L. Hippocampal gene expression dysregulation of Klotho, nuclear factor kappa B and tumor necrosis factor in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. J. Neuroinflamm. 10, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-10-53 (2013).

Mansoor, S. R. et al. Upregulation of klotho and erythropoietin contributes to the neuroprotection induced by curcumin-loaded nanoparticles in experimental model of chronic epilepsy. Brain Res. Bull. 142, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.08.010 (2018).

Xiang, T. et al. Klotho ameliorated cognitive deficits in a temporal lobe epilepsy rat model by inhibiting ferroptosis. Brain Res. 1772, 147668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147668 (2021).

Xiang, T., Luo, X., Ye, L., Huang, H. & Wu, Y. Klotho alleviates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation in a temporal lobe epilepsy rat model by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Epilepsy Behav. 128, 108509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108509 (2022).

Jiang, S. et al. The association of serum Klotho concentrations with hyperlipidemia prevalence and lipid levels among US adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 23(1), 1645. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16566-y (2023).

Zhang, Y., Shen, J., Su, H. & Lin, C. Association between composite dietary antioxidant index and epilepsy in American population: A cross-sectional study from NHANES. BMC Public Health 24(1), 2240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19794-y (2024).

Liu, Y., Hu, G., Zhang, M. & Lin, J. Association between dietary carbohydrate intake percentage and epilepsy prevalence in the NHANES 2013–2018: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Neurosci. 27(11), 1321–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415x.2024.2329481 (2024).

Chen, T., Wang, B., Lu, J. & Jing, L. Association of dietary vitamin K1 intake with epilepsy in adults in US: A cross-sectional study of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2018. BMC Public Health 24(1), 3125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20548-z (2024).

Iranpour, S. & Sabour, S. Inverse association between caffeine intake and depressive symptoms in US adults: Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2006. Psychiatry Res. 271, 732–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.004 (2019).

Sen, A., Capelli, V. & Husain, M. Cognition and dementia in older patients with epilepsy. Brain 141(6), 1592–1608. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy022 (2018).

Choi, H. et al. Predictors of incident epilepsy in older adults: The cardiovascular health study. Neurology 88(9), 870–877. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000003662 (2017).

Reddy, D. S., Thompson, W. & Calderara, G. Molecular mechanisms of sex differences in epilepsy and seizure susceptibility in chemical, genetic and acquired epileptogenesis. Neurosci. Lett. 750, 135753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135753 (2021).

Savic, I. Sex differences in human epilepsy. Exp. Neurol. 259, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.009 (2014).

Hu, Y. et al. Gender and socioeconomic disparities in global burden of epilepsy: An analysis of time trends from 1990 to 2017. Front. Neurol. 12, 643450. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.643450 (2021).

Meij, E., Haartsen, T. & Meijering, L. Enduring rural poverty: Stigma, class practices and social networks in a town in the Groninger Veenkoloniën. J. Rural Stud. 79, 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.031 (2020).

Yuan, Q. et al. A Klotho-derived peptide protects against kidney fibrosis by targeting TGF-β signaling. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 438. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28096-z (2022).

Kakar, R. S. et al. Peripheral Klotho and Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 36(5), 1274–1276. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28530 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Relationship of Klotho with cognition and dementia: Results from the NHANES 2011–2014 and Mendelian randomization study. Transl. Psychiatry 13(1), 337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02632-x (2023).

Chen, K. et al. Klotho deficiency causes heart aging via impairing the Nrf2-GR pathway. Circ. Res. 128(4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.317348 (2021).

Iijima, H. et al. Age-related matrix stiffening epigenetically regulates α-Klotho expression and compromises chondrocyte integrity. Nat. Commun. 14(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35359-2 (2023).

Wang, P. et al. Attenuation of osteoarthritis progression via locoregional delivery of Klotho-expressing plasmid DNA and Tanshinon IIA through a stem cell-homing hydrogel. J. Nanobiotechnol. 22(1), 325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02608-z (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Orally-active, clinically-translatable senolytics restore α-Klotho in mice and humans. EBioMedicine 77, 103912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103912 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the investigators of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Funding

The project supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (No. 1053320220796, No. 1053320221226).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Tianyi Long; Investigation, Minghong Chen, Junyu Chen, Xuerui Wang; Writing, Minghong Chen.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

NHANES was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board, and participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Chen, J., Wang, X. et al. Serum Klotho levels and epilepsy among U.S. adults in the NHANES 2013–2016: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 12218 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97112-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97112-1