Abstract

A laboratory investigation was conducted to evaluate the structural behavior of ferrocement composite panels (FCPs) incorporating expanded perlite lightweight aggregate (LWA) at varying volume fractions (55%, 35%, and 15%). Twelve lightweight FCPs (60 × 60 × 4 cm) were fabricated with one, two, or three layers of expanded rib lath and tested under three-point flexural loading. Structural response was assessed using digital image correlation (DIC) and theoretical analysis based on the thin plate theory. The results showed that increasing the number of rib lath layers significantly enhanced the first crack load (Fcr) and ultimate load (Fu), with improvements ranging from 11 to 224% in Fcr and 18 to 76% in Fu. Deflection at first crack (\({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\)) and ultimate load (\({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\)) increased by an average of 47% and 229%, respectively. Additionally, the use of perlite LWA increased \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) and \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\) by 29% and 26% compared to regular FCPs, highlighting its effectiveness in enhancing flexibility. DIC analysis identified transverse strain (εxx) as the most sensitive parameter for early crack detection. Taguchi optimization further revealed that the number of rib lath layers had a more significant impact on Fcr and Fu than perlite content. These findings suggest that a three-layer FCP system with 15% perlite replacement optimizes load-bearing capacity, making it well-suited for high-strength, lightweight applications such as modular buildings and prefabricated structural elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferrocement, a thin-walled construction material comprising cement mortar and wire mesh reinforcement, offers high tensile strength, crack resistance, and durability. It is increasingly used in housing, prefabricated elements, and structural retrofits. Various studies have investigated the mechanical properties of ferrocement elements by varying multiple influential components such as type and content of cementitious materials, aggregate composition, and type and number of reinforcing mesh layers1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. For instance, Al-Kubaisy and Jumaat9 investigated the flexural behavior of reinforced concrete slabs with ferrocement tension zone cover. They concluded that the use of ferrocement cover leads to an increase of the ultimate flexural load and the first crack load. Chithambaram and Kumar10 examined the flexural performance of two different thicknesses of FCPs reinforced with chicken wire mesh and bamboo. They produced twelve FCPs and compared their flexural test results with theoretical predictions. A recent study by Joyklad et al.11 showed that optimized ferrocement jackets—via tailored wire mesh and chemical anchoring—significantly enhance reinforced concrete slab performance by increasing peak load, deflection, and energy absorption while delaying debonding, offering a cost-effective, ductile alternative to fiber-reinforced polymer reinforcement. Sandeep et al.12 demonstrated that optimizing ferrocement panels with increased steel fiber content and additional wire grid layers significantly enhances their impact resistance by delaying crack initiation and reducing damage under both low- and high-velocity impacts. These findings highlight ferrocement’s potential for robust, energy-absorbing, and impact-resistant construction. Also, the study of Eltaly et al.13 demonstrated that ferrocement pipes, reinforced with various mesh types, maintain high strength and excellent fracture resistance—even after prolonged exposure to water/oil mixtures. Finite element modeling confirmed their robust performance, underscoring ferrocement’s durability and cost-effectiveness for oil pipeline construction. Another recent research highlighted that ferrocement, by using significantly less cement and steel, offers lower embodied energy and reduced carbon emissions compared to conventional materials14.

Lightweight aggregate (LWA) concrete, owing to its lower density compared to conventional concrete and its economic benefits—including reduced structural weight, enhanced thermal insulation, improved fire and freeze–thaw resistance, and lower cost—has become increasingly common. It is widely used in various structural applications such as frames, floors, partition walls, roof shells, folded plates, bridges, prefabricated structural elements, deep beams and ferrocement slabs15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Many studies have explored the use of LWAs in ferrocement mixtures, focusing on flexural behavior and crack propagation. Naveen and Suresh27 found that incorporating up to 30% blast furnace slag as light weight fine aggregate in ferrocement beams enhances strength and ductility, while the beams perform well under monotonic and repeated flexural loading. Moreover, Shaheen et al.28 investigated the flexural behavior and performance of lightweight ferrocement composite plates incorporating lightweight filler materials. In another study, Işıkdağ29 examined the deflection and cracking behavior of FCPs with expanded perlite-based mortar, finding that an increase in the number of wire mesh layers and cement content resulted in higher first crack loads, ultimate loads, and deflections. Similarly, Madadi et al.30,31,32,33,34 conducted multiple investigations using expanded perlite and clay in ferrocement mixtures to explore various properties of ferrocement elements. Despite these advances, gaps remain in optimizing the number of mesh layers and understanding crack patterns under varying LWA contents.

In engineering, the application of optimization methods underscores the significance of achieving optimal outcomes23,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. Evidence demonstrates that Taguchi is one method that successfully applied in the development of lightweight concrete42,43,44. The Taguchi method offers several advantages over conventional experimental design methods, including minimizing experimental costs, decreasing variability when approaching performance goals, and the ability to replicate optimal working conditions from the lab to real production environments45,46,47. In this regard, exploring the influence of LWAs on the flexural behavior of ferrocement elements, analyzing their properties and impacts, and optimizing their use becomes a compelling area of interest.

Given the escalating need for lightweight, affordable, and eco-friendly housing solutions, and in light of advancements in characterizing FCPs, there has been limited investigation into the structural behavior and crack propagation of FCPs incorporating LWAs. Specifically, there is a notable shortage of research utilizing advanced techniques such as digital image correlation (DIC) and the Taguchi method to address this need. This study aims to bridge these gaps by investigating the structural behavior of ferrocement composite panels (FCPs) incorporating varying levels of expanded perlite LWA and different reinforcement configurations. The main objectives of this research are:

-

1.

To evaluate the flexural performance, including the first crack load (Fcr) and the ultimate load (Fu), of FCPs with varying perlite contents and mesh reinforcement layers.

-

2.

To characterize strain fields and crack patterns using digital image correlation (DIC) techniques, offering precise insights into failure mechanisms.

-

3.

To optimize the design parameters (perlite volume and mesh configuration) using the Taguchi method to achieve the best balance of strength, ductility, and material efficiency.

This study is among the first to employ DIC techniques for crack and strain characterization in ferrocement panels and to use the Taguchi method for systematic optimization of design parameters. The findings will not only enhance the understanding of ferrocement behavior but also provide practical guidelines for the design of lightweight, sustainable, and high-performance structural elements.

Experimental program

Materials and mixture preparation

In this study, CEM II 52.5 Portland cement (according to ASTM C150/C595) was provided from Torbat cement factory (Iran). Sand passing through a 4.75-mm sieve with a density of 2600 kg/m3 and a fitness modulus of 2.45 were used as the fine aggregate (according to ASTM C33). Figure 1 illustrates the sieve analysis of the utilized sand. Expanded perlite (according to ASTM C330) with a maximum nominal size of 7 mm was incorporated into the ferrocement mixture (Fig. 2). The expanded perlite had a density of 380 kg/m3, with 1.1% and 18% water absorption values at 1 h and 24 h, respectively. The properties of the cement and expanded perlite are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. To reinforce the specimens, galvanized steel expanded rib lath was used, weighing 1.84 kg/m2 with dimensions of 2500 × 600 mm and a diameter of 10 mm. The specifications of the reinforcement system used in the FCPs are presented in Table 3.

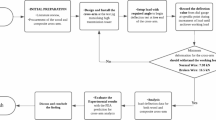

Design and testing of FCPs

In this study, twelve FCPs with the dimensions of 60 × 60 × 4 cm3 were manufactured. Four different mixture designs were created, each with varying percentages of expanded perlite (i.e. 55%, 35%, 15%, and 0 vol.%). The 0% level serves as a control, while 15% and 35% represent moderate replacement rates that balance workability, density reduction, and structural performance. The 55% level tests the upper limit of aggregate incorporation without significantly compromising strength. These selections were guided by previous research and practical considerations in mixing and casting. The water/cement ratio was 0.5 and remained constant for all the mixtures. Detailed mixture properties for the FCPs are provided in Table 4. The specimens were stored in the laboratory at a temperature of 20 ± 3 °C and a humidity level of 50% for a duration of 28 days. The FCPs were determined by slab series and number according to the number of expanded rib lath, as summarized in Table 5.

A three-point flexural test (according ASTM C7848) was performed using a servo-controlled testing machine with a maximum load capacity of 2000 kN. Displacement control loading was applied at a constant rate of 5 mm/min. The testing setup included a loading span of 50 cm, and the load–deflection curve was recorded using a data acquisition system. At the same time, DIC procedures were performed on the test specimens. DIC is an imaging technique used to measure full-field displacements and strains49,50. This method relies on capturing a sequence of images of the specimen’s surface—both before loading as a reference and during deformation under loading. To ensure accurate measurement, the specimen surface must have a random speckle pattern along with proper light intensity distribution. To minimize background vibrations from the testing machine, continuous video recordings of each slab panel were obtained during loading using a 1920 × 1080 pixel resolution camera equipped with a lens featuring an actual focal length (zoom) range of 6.1–30.5 mm. Key images were subsequently extracted from these recordings at the required time intervals. To further enhance image quality for precise crack detection and displacement measurement51, two surface mount device (SMD) ring lights were installed around the camera. The extracted images were then imported into the VIC-2D software package, where analyses were performed within the designated region of interest (ROI) to accurately assess deformation, crack initiation, and their progression across the slab panel’s cross-section.

The specimen placement and settings of tests along with a schematic diagram of applied loads and shear and bending changes are shown in Fig. 3.

Basic of formulae

The design of FCPs relies on establishing fundamental parameters, making it a crucial aspect of the process. Three key parameters that influence the characterization of reinforcement in FCPs include the total volume of reinforcement (Vf), the specific surface of reinforcement (Sr), and the effective modulus of the reinforcement.

Volume fraction of reinforcement (Vf)

The volume fraction of reinforcement, \(V_{f}\), used in the specimens is calculated by52

where Vm and Vc are calculated from the following relations

Specific surface of reinforcement (Sr)

The specific surface of expanded rib lath, \(S_{L}\), used in the specimens is calculated by53

First crack load and moment

The cracking load and moment at the first crack of the composite were determined using the expression developed by Logan and Shah54.

Ultimate load

In view of the low tensile strength of concrete, all the tensile forces are assumed to be taken by expanded rib lath and rebar. The compressive force taken by mortar is52

The tensile force contributed by expanded rib lath and rebar is

The moment of resistance of FCP with various numbers of expanded rib lath layers is calculated by52

where

The maximum deflection at the center of a partially loaded simply supported rectangular plate in which a uniform load \(q\) is distributed over a rectangular part with the sides \(u\) and \(v\) can be obtained using the following equation developed by Timoshenko et al.55. In this study, we considered u = a and v to be very small.

The ultimate load using moment relationship is calculated the following equation55:

where 0.09 is the coefficient for for the case of square plate. A value of 0.3 was assumed for Poisson’s ratio of mortar.

Results and discussion

First crack load and ultimate load

Experimental and theoretical values of first crack load and ultimate load for twelve FCPs are summarized in Table 6. The increase in expanded rib lath is evidently associated with a proportional increase in the first crack load and ultimate load, necessitating a greater force for cracking and reaching the ultimate capacity. As observed, the recorded Fcr (exp) and Fu (exp) values for FCPs incorporating perlite fall within the range of 577–2493 N and 2816–5746 N, respectively. Notably, FCPs containing perlite tend to exhibit an onset of cracking and ultimate capacity at a lower applied load compared to those without LWA (reference mix). This discrepancy can be attributed to the influence of perlite LWAs which are characterized by thin-walled structures with interconnected pores, contributing to a diminished strength in FCPs that incorporate it. As shown in Table 6, increasing the number of rib lath layers significantly enhances both the first Fcr and Fu, with improvements ranging from 11 to 224% for Fcr and 18 to 76% for Fu. These results highlight the strong synergistic effect between expanded rib lath reinforcement and perlite LWA. This trend is consistent with the findings of Minde et al.14, who reported increases of 13% in Fcr and 31% in Fu when perlite was combined with varying mesh layers, compared to control ferrocement panels.

Fcr (exp)/Fcr (theo) ratio for tested FCPs are in the range of 0.54–1.05 with an average of around 0.94 and Fu(exp)/Fu(theo) ratio was ranged from 0.98 to 1.21 with an average of around 1.04, indicating that the theoretical loads were found almost close to the experimental loads with an acceptable accuracy. This agreement is particularly significant when considering the modeling approach used for predicting Fcr and Fu.

In the analysis of structural elements, the initial crack formation is predominantly governed by the ferrocement mortar’s behavior under applied loads10. Consequently, Fcr is determined primarily by considering the contribution of the mortar and expanded rib lath layers, with reinforcement playing a minimal role at this stage. In contrast, Fu is computed by accounting for the combined influence of both the mortar and the reinforcement system, which contributes significantly to the ultimate load-bearing capacity.

The observed discrepancies between theoretical and experimental values, particularly for FCPs with a single expanded rib lath layer, can be attributed to the dominant role of the mortar section in these cases. Since the theoretical model primarily emphasizes the reinforcement contribution, it does not fully capture the influence of the mortar matrix56. As a result, FCPs with single-layer reinforcement exhibit more significant deviations between predicted and measured values, whereas FCPs with two or three rib lath layers show better alignment between theoretical and experimental results. This suggests that the predictive model performs more accurately in cases where the reinforcement contribution is substantial.

Additionally, Table 6 reveals that the average values for the experimental and theoretical ratios of Fu/Fcr of FCPs are approximately 2.36 and 2.75, respectively. This alignment is in accordance with findings documented in the literature57, suggesting that the onset of non-linear behavior in ferrocement typically commences at approximately 30–50% of Fu. This alignment further validates the theoretical approach, despite minor deviations attributed to experimental uncertainties, material inconsistencies, and variations in test conditions.

Overall, the findings reinforce the critical role of expanded rib lath reinforcement in enhancing the structural performance of FCPs. The results also highlight the limitations of theoretical models in capturing the full complexity of ferrocement behavior, particularly in cases where the mortar section plays a dominant role. Future refinements in predictive modeling should incorporate a more comprehensive assessment of the mortar’s contribution to improve accuracy, especially for lightly reinforced configurations.

Table 7 provides data on \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\), \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\), and DI for all FCPs. \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) denotes a point on the load–deflection curve where a departure from the initial linear stage occurs. The values of \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) for FCPs incorporating perlite range from 0.89 to 8.61 mm, while the corresponding values of \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\) range from 7.48 to 24.15 mm. A comparison of deflection results between lightweight FCPs and normal FCPs reveals that the mean values of \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) and \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\) for FCPs with perlite are approximately 29% and 26% higher, respectively, than those for normal FCPs. This underscores the positive impact of perlite in situations where increased deflection is desirable. The porous, low-density structure of perlite appears to permit greater deformation before reaching the ultimate limit, which can be particularly beneficial in applications where a higher deflection capacity is desirable. As shown in Table 7, increasing the number of rib lath layers resulted in an average increase of 47% in \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) and 229% in deflection at ultimate load \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\). This significant enhancement can be attributed to the improved load distribution and higher tensile reinforcement provided by the additional rib lath layers, which contribute to greater energy absorption and deformation capacity before failure.

Furthermore, the average DIs of perlite-incorporated FCPs are approximately 5% higher than those of normal FCPs, indicating that perlite contributes to enhancing the ductility of such specimens. This finding aligns with previous studies58. Tables 6 and 7 collectively suggest that the higher Fu/Fcr ratio and increased deflection in FCPs incorporating perlite result in a larger region between their cracking and ultimate points, reinforcing the greater ductility of perlite-incorporated FCPs compared to reference FCPs.

The FCP specimen P1-2, incorporating 55% expanded perlite LWA and a mesh volume fraction of 0.0032, exhibited deflection behavior and first crack and ultimate load capacities comparable to those of P2-3, which contained a lower LWA content of 33% but a higher mesh volume fraction of 0.0048. This observation suggests that the increased reinforcement in P2-3—achieved by the addition of one extra ERL layer, equivalent to an additional 0.0016 in mesh volume fraction—effectively compensates for the reduced amount of LWA in terms of structural performance. It also indicates that the benefits of increased reinforcement can offset the potential loss in ductility or deformability that might result from using a denser matrix. This balance highlights the importance of optimizing both LWA content and mesh configuration when designing ferrocement panels to achieve desired strength and serviceability characteristics without significantly increasing density or compromising performance.

Additionally, Table 7 reveals that the ductility indices of the tested FCPs span from 2.45 to 12.12, with an overall mean DI exceeding 4. This range reinforces the notion that the ferrocement system provides satisfactory ductility, supporting earlier findings by Nassif and Najm59. The combination of increased deflection and a higher Fu/Fcr ratio, particularly in perlite-enhanced panels, suggests that the material modifications lead to a more resilient and deformable structural response. Such behavior is crucial in applications where large deflections and energy absorption are required to prevent sudden or brittle failures. These results also mirror those of Mohana et al.60, where the addition of mesh layers significantly delayed failure and improved deflection capacity, particularly in 3- to 4-layer configurations.

The observed improvements in deflection and ductility for perlite-incorporated FCPs can also be linked to the microstructural characteristics of perlite, which modify the mortar’s behavior under load. These findings underscore the importance of controlling aggregate properties and reinforcement configurations in the design of ferrocement systems. Future research should further refine the predictive models to account for the combined effects of LWAs and the mortar matrix. Such enhancements would enable more precise estimations of deflection and ductility, thereby optimizing ferrocement panels for specific structural applications where ductility and flexibility are paramount.

Table 8 presents a comparative analysis of load-bearing capacity and density between the current study and previous research on FCPs. For example, Cheah and Ramli60 evaluated FCPs with dimensions of 350 × 125 × 30 mm and reported a flexural capacity of 4710 N and a density of 2246 kg/m3 for a conventional FCP reinforced with five layers of mesh. In contrast, the P2-3 FCP from the present study, incorporating 35% expanded perlite and three layers of expanded rib lath, achieved a 22% reduction in density along with an approximate 1.1% improvement in flexural capacity. Similarly, Işıkdağ30 investigated FCPs with perlite LWA reinforced with two layers of mesh and observed a flexural capacity that was 12% lower than that obtained in our study for panels with the same number of mesh layers. Moreover, Madadi et al.31 examined FCPs incorporating 10% Leca LWA with various mesh configurations and found flexural capacities that were 11.4% and 0.3% lower than those of our P2-2 and P2-3 FCPs, respectively.

These comparisons, despite differences in specimen dimensions and loading spans, collectively confirm the robust performance of FCPs incorporating expanded perlite LWA. The porous structure of expanded perlite, similar to the hollow spherical form of fly ash cenosphere industrial waste60, introduces air voids into the ferrocement mortar, leading to a significant reduction in density. This reduction not only contributes to weight savings and improved material efficiency but also maintains—and in some cases, slightly enhances—the structural capacity of the panels.

This suggests that expanded perlite LWA is a promising alternative to traditional aggregates in FCP applications, particularly in scenarios where reducing structural weight is critical without sacrificing load-bearing performance.

Load–deflection curves

Load–deflection relationships of FCPs are shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7. According to these figures, a linear relationship between load and deflection was observed up to the first crack load, while a non-linear behavior started until it reached the ultimate load. The curve slope reduces continuously and turns zero at peak load, then becomes negative at the post-peak regime. In most cases with the number of expanded rib lath layers increases from one to three, the ultimate load capacity is also increased, so that using three layers of expanded rib lath led to a higher ultimate load than those of one and two layers.

Therefore, in general, it can be mentioned that the flexural strength of FCPs increases with an increase in the number of expanded rib lath layers. This increase can be attributed to the increased mesh volume fraction of the expanded rib lath within the specimens, and the increased depth of mesh layers from the neutral axis of the section which resulted in an increased moment arm, leading to an increase in flexural strength. In some mix designs, the FCPs with two and three layers of expanded rib lath represent almost the same ultimate load while there is a large difference with the ultimate load of the FCPs with one expanded rib lath layer. This observation could be attributed to an almost negligible gap between the first and third layers of expanded rib lath, along with a considerable distance (resulting from the presence of rebars) between the first and second layers of expanded rib lath. Consistent findings were previously documented in the research conducted by Batson et al.4. They reported that the flexural strength demonstrates an upward trend as the number of mesh layers increases, especially when there is a greater separation between these layers. Furthermore, they noted a substantial enhancement in flexural strength when reinforcing rebars are positioned between the mesh layers, emphasizing that this improvement is attributed to the increased distance between the mesh layers.

Additionally, as shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7, specimens with two or three layers of expanded rib lath (ERL) exhibited a distinct horizontal plateau following the peak load, indicating a more ductile post-peak response. This behavior reflects the ability of the reinforced matrix to undergo further deformation without immediate failure. In contrast, specimens with only one ERL layer lacked a prominent horizontal segment after reaching peak load, suggesting a more brittle response and reduced ductility. This comparison highlights the role of reinforcement content in enhancing energy dissipation and deformability beyond the peak load, contributing to a more favorable failure mode.

The test results underscore that the flexural strength of FCPs is significantly influenced by both the number and the arrangement of expanded rib lath layers. Enhancements in ultimate load and ductility are achieved through increased mesh volume fraction and a larger effective moment arm, reinforcing the need for optimized layer spacing to fully exploit the reinforcing potential. These insights provide valuable guidance for the design and application of ferrocement systems where a balance between strength, ductility, and energy absorption is critical.

Crack patterns

The crack patterns of FCPs are represented in Fig. 8. Generally, many fine cracks parallel and perpendicular to the rebar were observed to be developed on all tested FCPs. On the surface of P1-1 and P2-1, a deep crack can be seen perpendicular to the embedded longitudinal rebar. The crack depth of FCPs significantly increases when the percent of sand replacement by expanded perlite LWA increases from 0 to 55%. It can be also seen in the FCPs of one mix design that the number of cracks is reduced by increasing the expanded rib lath layers. This is due to the fact that with an increase in the Asrl, the FCPs become less ductile and hence keeps the tension zone lower62. Furthermore, the use of longitudinal rebars in the FCPs reduces the stress applied to the concrete section of FCPs as a considerable stress of concrete is tolerated by longitudinal rebars63.

It was observed that specimens with a lower number of ERL layers primarily failed due to de-bonding between the reinforcement and the surrounding mortar. For example, the cracking patterns of specimens P1-1 and P2-1 (Fig. 8), each containing only a single ERL layer, clearly exhibit signs of de-bonding failure, indicating a weak bond at the reinforcement–mortar interface. De-bonding is a key concern, with high strain concentrations developing at this interface, often triggering early failure before the full load-bearing capacity of the panel is reached. In contrast, increasing the number of ERL layers significantly reduced the occurrence of de-bonding in the specimens. This improvement highlights the critical role of a higher reinforcement volume fraction in enhancing interfacial bonding, promoting better mechanical interlock, and distributing stresses more evenly across the ferrocement matrix. As a result, the structural integrity of the FCPs is improved, reducing the risk of premature separation and ensuring more reliable performance under applied loads. These findings emphasize the importance of adequate reinforcement not only for strength but also for effective stress transfer and long-term durability.

Flexural stress causes the initiation of cracking on the surface of FCPs. By an increase in loading, considerable stress is developed on longitudinal rebars which causes cracks to be formed alongside the longitudinal rebars on the surface of FCPs. Figure 9 illustrates typical flexural crack propagation and diagonal shear cracks within the shear spans. There were no shear cracks found anywhere near the supports for the entire tested FCPs, similar to the results reported in literatures64,65,66. As seen, the crack zone was wider at the maximum moment zone and the spacing between cracks gets closer by increasing the number of expanded rib lath layers. Furthermore, an increase in the number of micro-cracks with an increase in the number layers of expanded rib lath is clearly observed in the FCPs of P1-3, P2-3, and P3-3. Similar results were reported in the study of Işıkdağ29 who observed that the first cracking is accelerated and the crack width of lightweight FCPs is decreased as the number of wire mesh layers increased.

Strain field measurements using DIC

Figure 10 displays the outcomes of DIC analysis detailing the transverse (εxx), axial (εyy), and shear (εxy) strain fields for the P2-1 specimen under varying loads. The letters on the DIC contours correspond to specific points on the load-time curve. A clear trend is evident from the DIC analysis: all strain components increase progressively with the applied load. At the peak load, the comparison between the strain components reveals that the maximum transverse strain (εxx) is approximately 5.5 times higher than the maximum axial strain (εyy) and 1.6 times greater than the maximum shear strain (εxy). This disparity indicates that εxx is the most sensitive parameter for characterizing the surface deformation of ferrocement panels (FCPs), particularly in the early stages of crack initiation and propagation.

The observed strain patterns offer valuable insights into the failure mechanisms of the FCPs. The significant values of both εxx and εyy indicate that flexural deformations play a crucial role, whereas the lower magnitude of εxy suggests that, although shear deformation contributes to the overall strain field, it is not the dominant failure mechanism. Consequently, the failure mode of these panels can be interpreted as primarily flexural, compounded by secondary shear effects. This combined stress state underscores the complex interplay between flexural and shear forces in the failure process of ferrocement structures.

The DIC technique emerges as a potent method for detecting and characterizing cracks, especially those imperceptible to the naked eye. It accomplishes this by providing a comprehensive map of local deformations and crack developments. Notably, cracks that are difficult to observe on the surface of the P2-1 specimen under a 3000 N load become clearly visible on the corresponding DIC contour. This underscores the precision of the DIC technique in crack detection, consistent with findings in the study by Hamrat et al.62.

Statistical analysis

Taguchi method

The Taguchi method stands out as a prominent optimization technique employed in various engineering applications35,67. Developed by Genichi Taguchi68, the Taguchi method has been extensively applied to the realm of cement-based materials39,69,70,71, where it has proven to be a valuable tool for achieving optimal results in research and production processes alike. Noteworthy for its widespread use, this method offers distinct advantages over alternative approaches by effectively minimizing test expenses while ensuring optimal parameter determination for enhanced performance72. This unique feature makes it possible to leverage the optimization results of the Taguchi method for the practical production of specimens46.

S/N ratio

Taguchi frequently utilizes standard orthogonal arrays to analyze how different parameters affect procedures. In this process, a suitable loss function is integrated to estimate deviations between input values and the optimal output. The transformation of this loss function into a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio then enables its application in assessments and analyses. The followings are the forms of target functions that can be used in the case of current study:

-

(1)

Smaller is better, is applied in order to minimize the response. The S/N ratio is given by Eq. (14).

$$S/N = - 10*\log_{10} \left( {\frac{1}{n}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n} y_{i}^{2} } \right)$$(14) -

(2)

Larger is better, is applied in order to maximize the response. The S/N ratio is given by Eq. (15).

$$S/N = - 10*\log_{10} \left( {\frac{1}{n}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{n} \frac{1}{{y_{i}^{2} }}} \right)$$(15)

In this study, the target function was influenced by two key factors: (1) the volume content of LWA replaced and (2) the mesh (expanded rib lath) volume fraction employed in FCPs. Each factor was examined at four control levels for perlite volume content, and three control levels for the mesh volume fraction, as outlined in Table 9. The analysis was conducted based on each specific target function.

The main effects plot for the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of the load and deflection are shown in Figs. 11 and 12. Figure 11 shows the effect of percent of sand replacement by expanded perlite and mesh volume fraction on the S/N ratio of the experimental ultimate load and experimental first crack load. As seen, the S/N ratio for both Fu and Fcr loads increases with an increase in the mesh volume fraction from 0.0016 to 0.0048 and decreases with an increase in the percent of sand replacement by expanded perlite from 0 to 55%. This shows reducing the total weight of the FCPs leads to a decreased load carrying capacity.

Figure 12 shows the relation of S/N ratio with deflection at ultimate load and deflection at first crack load. Results show that the optimum values for the mesh volume fraction and percent of sand replacement by expanded perlite are 0.0016 and 15%, respectively, which led to have the least \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) and \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\). This affirms the favorable impact and mutual influence of factors in managing the deflection behavior of FCPs during particular loading phases.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine contribution of factors and effect of content of expanded perlite and mesh volume fraction on the loads and deflections. Results of ANOVA are shown in Tables 10, 11, 12 and 13 for Fu, Fcr, \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\) and \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\), respectively. The observed P values indicate the existence of statistically significant parameters and the higher F statistics values obtained for mesh volume fraction compared to those of expended perlite volume show that the number of expanded rib lath layers is a more effective factor than the volume content of LWA on improving the Fcr and Fu and reducing \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) and \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\) of the FCPs.

An in-depth evaluation of the ferrocement panels (FCPs) reveals that the optimum perlite replacement ratio is consistently around 15%, irrespective of whether the system has one, two, or three expanded rib lath layers. For single-layer systems, a 15% perlite ratio minimizes the adverse effects of weight reduction while maintaining a reasonable balance between load capacity and deflection. However, these systems inherently exhibit lower ultimate and first crack loads compared to multi-layer systems.

In FCPs with two or three layers, the contribution of the mesh is significantly enhanced. In these configurations, a higher mesh volume fraction—up to 0.0048—proves particularly beneficial for maximizing both the ultimate load (Fu) and first crack load (Fcr), as the additional reinforcement increases the effective moment arm and overall strength. Conversely, if minimizing deflections \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\) and \({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\) is the primary design goal, an optimal mesh volume fraction of 0.0016 (combined with the 15% perlite replacement) yields the best performance.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) further substantiates these findings. The results indicate that while both the perlite volume and the mesh volume fraction are statistically significant factors (with P values mostly below 0.05), the mesh volume fraction consistently shows higher F-statistic values (e.g., F = 17.36 for Fu and F = 11.14 for Fcr). This statistical evidence confirms that the number of expanded rib lath layers—and, by extension, the mesh volume fraction—is the dominant factor in enhancing load capacity and reducing deflections, with the perlite content playing a secondary role.

In summary, for maximum load capacity, a three-layer system with a high mesh volume fraction of 0.0048 and a 15% perlite replacement ratio is recommended, as this configuration leverages increased reinforcement and an effective moment arm to maximize both ultimate and first crack loads. Conversely, when serviceability is paramount, a mesh volume fraction of 0.0016 combined with a 15% perlite replacement yields the lowest deflections. In summary, regardless of the reinforcement configuration, a 15% perlite replacement ratio is optimal, with the mesh volume fraction and number of layers adjusted based on whether the design prioritizes load capacity or deflection control.

Conclusions

This research examines the flexural characteristics of FCPs incorporating different volumes of EPA and varying layers of expanded rib lath by using experimental, theoretical, and statistical analyses. The DIC and Taguchi methods were employed to evaluate the cracking behavior and to optimize the parameters of FCPs. The key findings are outlined as follows:

-

1.

The results of theoretical analysis were in close agreement with those obtained from the load–deflection curves, which further confirmed the applicability of the theoretical methods in prediction of structural behavior of FCPs.

-

2.

The significant disparity in strain components obtained by DIC analysis indicates that transverse strain (εxx) is the most sensitive parameter for characterizing surface deformation in ferrocement panels (FCPs), especially during early crack initiation and propagation.

-

3.

Increasing the number of expanded rib lath layers enhanced the ultimate load by 18–76% and increased deflection at ultimate load by 30–140%, while reducing the ductility index by 17–80% across all mixture designs.

-

4.

A three-layer FCP system with a 15% perlite replacement and a high mesh volume fraction (0.0048) maximizes ultimate and first crack loads—achieving up to 76% improvement in load capacity compared to single-layer systems, which inherently exhibit lower performance.

-

5.

FCPs incorporating perlite showed mean first crack deflection (\({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{{\text{cr}}}} }}\)) and ultimate deflection (\({\text{D}}_{{{\text{F}}_{{\text{u}}} }}\)) values that were 29% and 26% higher, respectively, compared to normal FCPs.

-

6.

Statistical (ANOVA) analysis confirmed that the number of expanded rib lath layers (mesh volume fraction) is the dominant factor for improving loads (F = 17.36 for Fu, F = 11.14 for Fcr) and controlling deflections; the optimal condition for minimum deflection is achieved with a mesh volume fraction of 0.0016 combined with 15% perlite replacement.

This study highlights the potential of optimized ferrocement panels with lightweight aggregates and layered reinforcement as an effective solution for sustainable construction. By enhancing strength, flexibility, and material efficiency, these panels offer a promising approach for lightweight, durable, and eco-friendly building systems. The integration of DIC and Taguchi optimization provided valuable insights into deformation behavior and parameter optimization. Future research should focus on the long-term durability of these panels under environmental conditions, dynamic and impact loading performance, and advanced numerical modeling. Field-scale validation and sustainability assessments, including cost and life cycle analysis, are also recommended to support practical implementation in lightweight, high-performance construction systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FCP:

-

Ferrocement composite plates

- EPA:

-

Expanded perlite aggregate

- V f :

-

Volume fraction of reinforcement

- S r :

-

Specific surface of reinforcement

- V m :

-

Volume of mesh

- V c :

-

Volume of ferrocement section

- N:

-

Number of expanded rib lath

- Wm :

-

Weight of a mesh per unit area

- γm :

-

Density of steel

- h:

-

Thickness of ferrocement panel

- A:

-

Sectional area of ferrocement

- SL :

-

Specific surface of the expanded rib lath

- d b :

-

Diameter or equivalent diameter of the wire

- \(\sigma_{cr}\) :

-

First crack stress

- \(F_{ru}\) :

-

Modulus of rupture of mortar

- \(M_{cr}\) :

-

Moment at first crack

- b:

-

Width of ferrocement section

- a:

-

Depth of the equivalent stress block

- L :

-

Loading span

- \(f_{cd}\) :

-

Characteristic strength of mortar

- \(F_{yl}\) :

-

Yield strength of expanded rib lath

- \(F_{yr}\) :

-

Yield strength of rebar

- \(A_{sl}\) :

-

Area of expanded rib lath

- \(A_{r}\) :

-

Area of rebar

- Fu :

-

Ultimate load

- Dcr :

-

Deflection at cracking load

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- S/N :

-

Signal-to-noise ratio

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

References

Masood, A., Arif, M., Akhtar, S. & Haquie, M. Performance of ferrocement panels in different environments. Cem. Concr. Res. 33, 555–562 (2003).

Mansur, M. A., Maalej, M. & Ismail, M. Study on corrosion durability of ferrocement. ACI Mater. J. 105, 28–34 (2008).

Greepala, V. & Nimityongskul, P. Structural integrity of ferrocement panels exposed to fire. Cem. Concr. Compos. 30, 419–430 (2008).

Batson, G. B. et al. Guide for the design, construction, and repair of ferrocement. ACI Struct. J. 85, 325–351 (1988).

Mazhar, M. A., Alam, P., Kamran, M., Ahmad, S. & Junaid, S. Recent Developments and Innovations in the Sustainable Production of Concrete 533–548 (Elsevier, 2025).

Elsamak, G. et al. Anchored and epoxied ferrocement strips for improving flexural performance of two-way reinforced concrete slabs. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04314 (2025).

Minde, P. & Kulkarni, M. Revolutionizing Indian construction sector with sustainable modular LGSF-ferron composite construction technology. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 10, 1–17 (2025).

Sathe, S., Dandin, S. & Kangda, M. Z. Comparative study on structural behavior of fibrous-ferro-cement panel reinforced with welded and expanded wire grid subjected to flexural loads. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 8, 1–19 (2025).

Al-Kubaisy, M. & Jumaat, M. Z. Flexural behaviour of reinforced concrete slabs with ferrocement tension zone cover. Constr. Build. Mater. 14, 245–252 (2000).

Chithambaram, S. J. & Kumar, S. Flexural behaviour of bamboo based ferrocement slab panels with flyash. Constr. Build. Mater. 134, 641–648 (2017).

Joyklad, P. et al. Structural behavior of RC one-way slabs strengthened with ferrocement and FRP composites. Eng. Fail. Anal. 161, 108328 (2024).

Sathe, S., Kangda, M. Z., Khan, M. A., Alharbi, Y. R. & Qamar, O. Structural performance of ferrocement panels under low-and high-velocity impact load. ACS Omega 8, 41120–41133 (2023).

Eltaly, B. A., Shaheen, Y. B., Salem, M. & Hamoda, A. Ferrocement oil pipes exposed to critical conditions and using various types of reinforcement mesh: Experimental and numerical studies. Structures 66, 106780 (2024).

Minde, P., Bhagat, D., Patil, M. & Kulkarni, M. A state-of-the-art review of ferrocement as a sustainable construction material in the Indian context. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.250 (2023).

Topçu, İB. & Işıkdağ, B. Effect of expanded perlite aggregate on the properties of lightweight concrete. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 204, 34–38 (2008).

Bingöl, A. F. & Gül, R. Compressive Strength of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete Exposed to High Temperatures (2004).

Memon, N. A., Sumadi, S. R. & Ramli, M. Ferrocement encased lightweight aerated concrete: A novel approach to produce sandwich composite. Mater. Lett. 61, 4035–4038 (2007).

Topçu, İB. & Işıkdağ, B. Manufacture of high heat conductivity resistant clay bricks containing perlite. Build. Environ. 42, 3540–3546 (2007).

Demirboğa, R. & Gül, R. The effects of expanded perlite aggregate, silica fume and fly ash on the thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 33, 723–727 (2003).

Seyhan, I. Future of Perlite and Light Construction Materials Industry in Turkey and world, vol. 1. National Perlite Congress, MTA, Turkey Geology Association.

Maso, J. (UNESCO Report for Karadeniz Tech. Univ., Dept. of Civil Engn, 1978).

Wang, S., Naaman, A. E. & Li, V. C. Bending response of hybrid ferrocement plates with meshes and fibers. J. Ferrocem. 34, 275–288 (2004).

Eskandari, H. & Madadi, A. Investigation of ferrocement channels using experimental and finite element analysis. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 18, 769–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2015.05.008 (2015).

Shakir, Q. M. & Hannon, H. K. Innovative model of precast RC curved hybrid deep beams composed partially with high-performance concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49, 6045–6060 (2024).

Shakir, Q. M. & Hanoon, H. K. New models for reinforced concrete precast hybrid deep beams under static loads with curved hybridization. Structures 54, 1007–1025 (2023).

Shakir, Q. M. & Hannon, H. K. A novel hybrid model of reinforced concrete deep beams with curved hybridization. J. Teknol. 85, 31–39 (2023).

Naveen, G. & Suresh, G. Experimental study on light weight ferrocement beam under monotonic and repeated flexural loading. Int. J. Civ. Struct. Eng. 3, 294 (2012).

Shaheen, Y. B., Soliman, N. M. & Kotb, H. A. Flexural behavior of lightweight composite ferrocement plates. Concr. Res. Lett. 6, 69–92 (2015).

Işıkdağ, B. Characterization of lightweight ferrocement panels containing expanded perlite-based mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 81, 15–23 (2015).

Madadi, A., Eskandari-Naddaf, H. & Gharouni-Nik, M. Lightweight ferrocement matrix compressive behavior: Experiments versus finite element analysis. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 42, 1–13 (2017).

Madadi, A., Eskandari-Naddaf, H., Shadnia, R. & Zhang, L. Characterization of ferrocement slab panels containing lightweight expanded clay aggregate using digital image correlation technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 180, 464–476 (2018).

Madadi, A., Eskandari-Naddaf, H., Shadnia, R. & Zhang, L. Digital image correlation to characterize the flexural behavior of lightweight ferrocement slab panels. Constr. Build. Mater. 189, 967–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.079 (2018).

Madadi, A., Tasdighi, M. & Eskandari-Naddaf, H. Structural response of ferrocement panels incorporating lightweight expanded clay and perlite aggregates: Experimental, theoretical and statistical analysis. Eng. Struct. 188, 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.03.038 (2019).

Yan, G. et al. Effect of perlite powder on properties of structural lightweight concrete with perlite aggregate. Struct. Eng. Mech. 84, 393–411 (2022).

Korouzhdeh, T., Eskandari-Naddaf, H. & Gharouni-Nik, M. An Improved ant colony model for cost optimization of composite beams. Appl. Artif. Intell. 31, 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2017.1296681 (2017).

Eskandari, H. & Pakzad, A. Applying simplex lattice in optimizing self-compaction concrete compressive strength. Asian J. Civ. Eng. (BHRC) 16, 775–787 (2015).

Chauhan, R., Singh, T., Kumar, N., Patnaik, A. & Thakur, N. Experimental investigation and optimization of impinging jet solar thermal collector by Taguchi method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 116, 100–109 (2017).

Eskandari, H. & Korouzhdeh, T. Cost optimization and sensitivity analysis of composite beams. Civ. Eng. J. 2, 52–62 (2016).

Eskandari-Naddaf, H. & Azimi-Pour, M. Performance evaluation of dry-pressed concrete curbs with variable cement grades by using Taguchi method. Ain Shams Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2016.09.004 (2016).

Shariat, M., Shariati, M., Madadi, A. & Wakil, K. Computational Lagrangian multiplier method by using for optimization and sensitivity analysis of rectangular reinforced concrete beams. Steel Compos. Struct. 29, 243–256. https://doi.org/10.12989/scs.2018.29.2.243 (2018).

Raisi, K., Abazarsa, M. & Yu, T. Corrosion detection of steel-reinforced concrete specimens using synthetic aperture radar. In Nondestructive Characterization and Monitoring of Advanced Materials, Aerospace, Civil Infrastructure, and Transportation XVIII, 182–196 (SPIE).

Dulsang, N. et al. Optimizing mix proportion of lightweight concrete containing plastic waste by Taguchi method. Adv. Mater. Res. 931, 431–435 (2014).

Dulsang, N., Kasemsiri, P., Posi, P., Hiziroglu, S. & Chindaprasirt, P. Characterization of an environment friendly lightweight concrete containing ethyl vinyl acetate waste. Mater. Des. 96, 350–356 (2016).

Xu, Y., Jiang, L., Xu, J. & Li, Y. Mechanical properties of expanded polystyrene lightweight aggregate concrete and brick. Constr. Build. Mater. 27, 32–38 (2012).

Türkmen, İ, Gül, R., Çel, K. C. & Dem Rboğa, R. Determination by the Taguchi method of optimum conditions for mechanical properties of high strength concrete with admixtures of silica fume and blast furnace slag. Civ. Eng. Environ. Syst. 20, 105–118 (2003).

Ozbay, E., Oztas, A., Baykasoglu, A. & Ozbebek, H. Investigating mix proportions of high strength self compacting concrete by using Taguchi method. Constr. Build. Mater. 23, 694–702 (2009).

Ghanei, A., Eskandari-Naddaf, H., Ozbakkaloglu, T. & Davoodi, A. Electrochemical and statistical analyses of the combined effect of air-entraining admixture and micro-silica on corrosion of reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 262, 120768 (2020).

Standard, A.

Roux, S., Hild, F. & Berthaud, Y. Correlation image velocimetry: A spectral approach. Appl. Opt. 41, 108–115 (2002).

Orteu, J.-J. 3-D computer vision in experimental mechanics. Opt. Lasers Eng. 47, 282–291 (2009).

Caduff, D. & Van Mier, J. G. Analysis of compressive fracture of three different concretes by means of 3D-digital image correlation and vacuum impregnation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 32, 281–290 (2010).

Batson, G. B. et al. Guide for the design, construction, and repair of ferrocement. ACI Struct. J. 85(3), 325–351 (1993).

Balaguru, P. & Batson, G. State-of-the-art report on ferrocement. ACI Committee 549 (1997).

Logan, D. & Shaw, S. Moment capacity and cracking behavior of ferrocement in flexure. J. Proc. 70, 799–804 (1973).

Timoshenko, S. & Woinowsky-Krieger, S. Theory of Plates and Shells (1959).

Hago, A., Al-Jabri, K., Alnuaimi, A., Al-Moqbali, H. & Al-Kubaisy, M. Ultimate and service behavior of ferrocement roof slab panels. Constr. Build. Mater. 19, 31–37 (2005).

Bazant, Z. P. Fracture Mechanics of Concrete Structures: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Fracture Mechanics of Concrete Structures (FraMCoS1), held at Beaver Run Resort, Breckenridge, Colorado, USA, 1–5 June 1992. vol. 1 (CRC Press, 1992).

Khonsari, S., Eslami, E. & Anvari, A. Effects of expanded perlite aggregate (EPA) on the mechanical behavior of lightweight concrete. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Fracture and Mechanics of Concrete and Concrete Structure (FraMCoS-7), Jeju, Korea,1354–1361.

Nassif, H. H. & Najm, H. Experimental and analytical investigation of ferrocement–concrete composite beams. Cem. Concr. Compos. 26, 787–796 (2004).

Mohana, R., Prabavathy, S. & Bharathi, S. L. Sustainable utilization of industrial wastes for the cleaner production of ferrocement structures: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 291, 125916 (2021).

Cheah, C. B. & Ramli, M. Load capacity and crack development characteristics of HCWA–DSF high strength mortar ferrocement panels in flexure. Constr. Build. Mater. 36, 348–357 (2012).

Hamrat, M., Boulekbache, B., Chemrouk, M. & Amziane, S. Flexural cracking behavior of normal strength, high strength and high strength fiber concrete beams, using digital image correlation technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 106, 678–692 (2016).

Choi, S., Won, M. C., Sudoi, E. & Nasrazadani, S. Horizontal Cracking Mechanism in CRCP (2009).

Basunbul, I., Saleem, M. & Al-Sulaimani, G. Flexural behavior of ferrocement sandwich panels. Cem. Concr. Compos. 13, 21–28 (1991).

Cheah, C. B. & Ramli, M. The structural behaviour of HCWA ferrocement–reinforced concrete composite slabs. Compos. B Eng. 51, 68–78 (2013).

Yang, K.-H., Mun, J.-H. & Kim, G.-H. Flexural behavior of post-tensioned normal-strength lightweight concrete one-way slabs. Eng. Struct. 56, 1295–1307 (2013).

Korouzhdeh, T. & Eskandari-Naddaf, H. Cost-safety optimization of steel-concrete composite beams using standardized formulation. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 22, 523–532 (2018).

Roy, R. K. A primer on the Taguchi Method (Society of Manufacturing Engineers, 2010).

Sevinç, A. H., Durgun, M. Y. & Eken, M. A Taguchi approach for investigating the engineering properties of concretes incorporating barite, colemanite, basaltic pumice and ground blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 135, 343–351 (2017).

Joshaghani, A., Ramezanianpour, A. A., Ataei, O. & Golroo, A. Optimizing pervious concrete pavement mixture design by using the Taguchi method. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 317–325 (2015).

Ghanei, A., Eskandari-Naddaf, H. & Davoodi, A. Corrosion behavior and optimization of air-entrained reinforced concrete, incorporating microsilica. Struct. Concr. 19, 1472–1480 (2018).

Shaji, S. & Radhakrishnan, V. Analysis of process parameters in surface grinding with graphite as lubricant based on the Taguchi method. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 141, 51–59 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by financial grants from “the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52104122)”, “the Open Project of Engineering Research Center of Phosphorus Resources Development and Utilization of Ministry of Education (LKF2021007)”, and “the Natural fund project of Fujian Province Science and Technology Department (2024J01964)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhengyu Wu: Writing—review and editing, project administration, resources, funding acquisition, conceptualization. Amirhossein Madadi: Writing—original draft, visualization, investigation, formal analysis, supervision, software, data curation. Tzuyang Yu: Review and editing—supervision—adminstrated revised manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Z., Madadi, A. & Yu, T. Structural analysis of ferrocement composite panels with expanded perlite based mortar. Sci Rep 15, 16831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97114-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97114-z