Abstract

The western region of China is characterized by abundant coal resources but scarce water resources, and underground reservoir systems have been proposed to mitigate this mismatch. However, during the operation of these reservoirs, fluctuating water levels cause coal pillar dams to be prone to damage due to the combined effects of in-situ stress and water immersion. In this study, cyclic loading-unloading experiments and nuclear magnetic resonance tests were performed on coal samples with varying immersion heights to investigate their mechanical behavior. The results showed that immersion leads to the mechanical properties exhibiting a trend of “short-term strengthening followed by significant weakening”. Unsoaked coal samples exhibited brittle characteristics, while immersed samples showed ductile behavior, with stress fluctuations after reaching peak load. Pore structure analysis revealed that higher immersion heights caused significant damage, with micropores evolving into mesopores and macropores, weakening the mechanical strength of the coal samples. The interaction between water and coal revealed a “compaction strengthening—damage softening” mechanism: at lower immersion heights, water infiltration created micropores that buffered external loads, resulting in compaction strengthening. At higher immersion levels, however, deeper water penetration triggered physicochemical interactions, generating macropores and microcracks that reduced mechanical strength. This study provides both macroscopic deformation-failure analysis and microscopic mechanistic insights into water-induced damage, aiming to enhance the stability and safety of coal pillar dams in underground reservoir systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

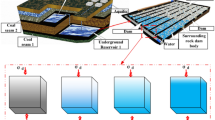

Coal will remain the critical source of energy in China for a long time1,2. The coal-rich yet water-scarce mining regions of western China face a critical challenge of balancing the spatial distribution of these two vital resources3, directly impacting sustainable coal resource development in the region4. Underground reservoir systems have emerged as a solution by facilitating water recycling and reuse, thereby enabling effective protection and utilization of water resources5. In coal mining, coal pillars are retained to support overlying strata and prevent mine shafts or underground tunnels induced by goaf formation. The stability of coal pillar dams constitutes a key factor in ensuring both safety and structural integrity of underground water storage systems6,7.

When coal pillar dams are exposed to underground reservoirs, they experience combined stress fields and water immersion, leading to alterations in mechanical strength and internal structure. Under stress-seepage coupling effects, coal pillar dams become increasingly prone to failure, potentially culminating in collapse8,9. Water significantly modulates rock deformation behavior, where reduced water content suppresses expansion and microcrack formation10. Numerous studies have explored the effects of factors such as wet-dry cycles, water content, and immersion time on rock deformation. It has been found that the number of wet-dry cycles significantly affects the water absorption of coal samples, with physical and chemical interactions between water and coal forming new pores during the process11. As the number of wet-dry cycles increases, water content initially rises rapidly before stabilizing12,13. Moreover, increasing water content enhances the plasticity of coal rocks14,15, with elastic modulus, cohesion, and internal friction angle all decreasing as water content rises16,17,18,19. Coal pillars are immersed in reservoirs for long periods, and the duration of immersion is also one of the key factors affecting the deformation of the coal body. Prolonged immersion increases the porosity of coal samples, further weakening their mechanical properties20.

Regarding the stability study of water in coal mine underground reservoirs, scholars have conducted a substantial amount of research mainly by means of numerical simulation, and have obtained abundant results. By developing a numerical model of coupled flow-solidity of coal mine underground reservoir under mining water flooding, the instability characteristics of coal pillar dams at the engineering scale were investigated, and the progressive damage mechanism of water on coal pillars was revealed21. Fracture development and evolution within coal pillars are key factors affecting their stability22. UDEC-based simulations demonstrate how water saturation weakens coal pillar strength, with deterioration rates stabilizing over time under long-term immersion23.

In summary, substantial research has been conducted on the impact of water on the mechanical properties of coal and the stability of underground reservoirs. These studies generally confirm that water weakens coal’s mechanical characteristics, leading to the instability of underground reservoirs. However, during the operational lifespan of underground reservoirs, water levels are not constant24, and the load-bearing capacity of coal pillars varies with different immersion heights. Therefore, understanding the effects of varying water immersion heights on the mechanical behavior of coal pillars is critical for ensuring the safe operation of underground reservoir systems. Nevertheless, there is limited research on the impact of different immersion heights on the mechanical properties of coal, warranting further investigation. This study explores the effects of varying immersion heights on the strength of coal samples and analyzes the energy evolution laws. Using NMR technology, the internal damage mechanisms of coal samples under different immersion heights are elucidated.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

In this study, 25 cylindrical coal samples with dimensions of 50 mm(diameter)×100 mm, height were prepared, and all sample surfaces were polished to ensure a flatness error of less than 0.02 mm (Fig. 1a). To minimize the impact of coal sample heterogeneity on the experimental results, P-wave velocity tests were conducted on all 25 samples (Fig. 1b), from which 10 samples with similar P-wave velocities were chosen for the experiments, as shown in Table 1. The sample numbering follows the principles below:

-

①

UCT indicates coal samples used for uniaxial compression tests

-

②

H indicates coal samples for water immersion experiments, where the numbers “00,” “25,” “50,” and “75” represent different immersion heights. The letter “M” denotes samples used for cyclic loading-unloading experiments, while “N” indicates samples used for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) testing.

Experimental methods

The experimental apparatus used in this study is the “Microcomputer-controlled electronic universal testing machine” from the College of Aerospace Engineering at Chongqing University. This equipment primarily consists of a microcomputer-controlled testing system and a data acquisition system (Fig. 2). It is driven by a servo motor, which moves the crossbeam up and down through a transmission mechanism to achieve cyclic loading and unloading. After the P-wave velocity tests, the coal samples were dried at low temperatures. Uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) represents the maximum stress that a material can withstand under unidirectional compressive force25,26. Two samples were selected for uniaxial compression testing to determine the UCS of the coal samples, providing a basis for designing the stress path for cyclic loading and unloading.

The remaining eight coal samples were subjected to different water immersion heights (0 mm for unsoaked, 25 mm, 50 mm, and 75 mm, as shown in Fig. 3a), with each group consisting of two samples. The immersion time for all samples was 24 h. One sample from each group underwent cyclic loading-unloading tests, while the other sample was used for NMR testing.

According to the existing research, the effect of mining disturbance caused by coal seam mining is mainly related to the mining stress, stress amplitude, and the number of cycles27,28. Therefore, in order to simulate the stress state of coal pillar dams under the influence of mining disturbance, this study designs the cyclic loading and unloading disturbance of “elevated stress level in the gradient—reduced magnitude in the gradient” as the stress path (Fig. 3b). The purpose of this study is to investigate the mechanism of water on coal samples under different immersion heights, in order to avoid the rapid destruction of the samples due to the high initial loading stress which makes it difficult to identify the differences of the coal samples under different immersion heights, this experiment was designed with an initial loading stress of 60% UCS. And the experiment proceeded according to the following steps:

-

①

The samples were loaded at a rate of 400 N/s to 60% of the UCS, followed by a 30-minute constant load hold.

-

②

Cyclic loading-unloading with decreasing stress amplitude and rising stress level was performed to simulate the stress state during mine disturbances. Ten cycles of loading and unloading were designed for each stress level, with the loading amplitude decreasing by 1% UCS per half cycle.

-

③

After the first stress level cycle was completed, the stress level was increased to 70% UCS, and the procedure in step 2 was repeated.

-

④

The process was repeated until the coal sample failed.

The cyclic loading-unloading experiments provided the macroscopic mechanical characteristics of coal sample failure. As coal is inherently porous, NMR technology was used to assess the internal structural damage of the coal samples, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the damage mechanisms under varying water immersion heights. The NMR tests were conducted using the MacroMR12-15OH-I low-field nuclear magnetic resonance device, manufactured by Niumag Corporation (Fig. 3c). The permanent magnet has a magnetic induction intensity of 0.3 ± 0.05 T, and the proton resonance frequency is 23 MHz, with the magnet being held at a constant temperature of 32 °C. The CPMG pulse sequence was used, with NECH = 1000 and TW = 1200 ms. In NMR tests, the T2 relaxation time reflects pore size information and it is positively correlated with pore diameter. By processing the relaxation data, the T2 distribution curve and the corresponding porosity components of the coal samples were obtained. Additionally, a larger amplitude and area of peaks in the T2 spectrum indicate a greater number of pores of that size. The relationship between transverse relaxation time (T2) and pore diameter is expressed as:

where \(\:{T}_{2}\) is the relaxation time, \(\:{\rho\:}_{2}\) is the surface relaxivity, \(\:\frac{S}{V}\) is the specific surface area, \(\:{F}_{s}\) is a geometric factor, and \(\:r\) is the characteristic pore size.

Data analysis methods

-

(1)

Calculation of general mechanical parameters.

The loading modulus (LM) reflects the stiffness of the material during loading, while the unloading modulus (UM) indicates its recovery ability during unloading. These values are calculated using the following equations:

where \(\:{E}_{l}\) is the loading modulus, \(\:{\varDelta\:\sigma\:}_{+}\) is the stress increment during loading, and \(\:{\varDelta\:\epsilon\:}_{+}\) is the strain increment during loading; \(\:{E}_{u}\) is the unloading modulus, \(\:{\varDelta\:\sigma\:}_{-}\) is the stress increment during unloading, and \(\:{\varDelta\:\epsilon\:}_{-}\) is the strain increment during unloading.

The ratio of the loading modulus to the unloading modulus, defined as the load-unload response ratio (LURR), represents the non-linear behavior of the material during loading and unloading:

A value close to 1 indicates good elastic recovery ability, while a value greater than 1 suggests internal damage to the material.

-

(2)

Calculation of energy evolution.

For analytical purposes, a loaded coal sample can be treated as a thermally and energetically isolated system without heat or mass exchange with the environment27. Thus, the total input energy can be divided into elastic strain energy and dissipated strain energy (Fig. 4), which can be calculated using the following Eqs29,30:

Where,

Results and discussions

Characteristics of stress-strain curves

The stress-strain curves obtained from uniaxial compression tests on coal samples are shown in Fig. 5. The peak stress values of the coal samples were 18.74 MPa and 18.68 MPa, respectively, indicating comparable peak strength and low strength anisotropy among the samples based on pre-test P-wave velocity screening. This demonstrates that the coal samples are relatively homogeneous, minimizing experimental variability. The average peak stress of the two samples was 18.71 MPa, which served as the basis for designing the stress path for the cyclic loading-unloading experiments.

The stress-strain curves of coal samples under different water immersion heights are presented in Fig. 6. Based on the slope variations of the stress-strain curves before the peak stress, three distinct stages can be identified: compaction, elastic deformation, and crack propagation31. In the compaction stage, the curve exhibits a concave upward trend, reflecting pore compression under external load. Notably, the coal sample at the 25 mm immersion height displayed the longest compaction stage duration. In the elastic deformation stage, the stress-strain curve is approximately linear. In the crack propagation stage, a pronounced hysteresis loop emerges accompanied by crack extension and new fracture formation. Upon reaching the peak stress, the coal sample experiences a rapid decrease in stress, indicating structural failure.

Water exerts a softening effect on coal, inducing more plastic behavior32. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the stress-strain curve of unsoaked coal remains continuous before the peak stress. Upon reaching peak strength, its bearing capacity rapidly declines, characterizing brittle failure. Conversely, immersed coal samples demonstrate post-peak stress fluctuations with residual bearing capacity, exhibiting a ductile failure process marked by sequential stress surges and drops.

Deformation and failure characteristics

The peak load and the peak strain

Peak stress represents the maximum load-bearing capacity of a material during deformation. Peak strain corresponds to the material’s deformation at peak stress, quantifying its ductility under ultimate loading conditions.

As shown in Fig. 7, the peak stress of coal samples under different immersion heights exhibits a “slight increase followed by continuous decrease” pattern, while the peak strain shows little variation with immersion height. At low immersion heights, water penetration increases the porosity in the lower part of the coal sample, enabling it to absorb more external energy during the compaction stage. This leads to a slight increase in peak stress compared to the unsoaked samples. However, elevated immersion heights intensify water-induced softening, weakening interparticle cohesion and inducing progressive degradation of mechanical strength, as evidenced by declining peak stress33.

Loading modulus, unloading modulus, and load-unload response ratio

The trends in LM, UM, and LURR across immersion heights are shown in Fig. 8. Each step represents a cycle of ten loading-unloading events, with axial load incrementally increased between steps. The experimental results indicate that the samples failed after 40 cycles for unsoaked, 25 mm, and 50 mm immersion heights, while the sample at 75 mm immersion height failed after 20 cycles.

For all immersion heights, the loading modulus initially increases then decreases cyclically. Similarly, the unloading modulus follows an identical trend. Interestingly, a significant increase in the unloading modulus is observed during the transition from the first to the second loading-unloading cycle of each step. This occurs because the coal samples experience large plastic deformation under a compressive load higher than the pre-hold stress, weakening their recovery capacity. LURR values approaching 1 in the early step cycles indicate minimal internal damage, signifying preserved structural integrity and mechanical performance. Conversely, LURR values exceeding 1 in the later cycles suggest that microcracks or other forms of damage have begun to accumulate, causing irreversible deformation.

Irreversible strain

Irreversible strain refers to the permanent deformation accumulated when a material experiences stresses exceeding its elastic limit34. To quantify the contribution of each cycle to overall irreversible deformation, we define the Damage Contribution (DC) as the ratio of the cumulative irreversible strain per cycle to total irreversible strain. By analysing the DC, the influence of distinct loading stages on the overall damage progression can be elucidated, thereby revealing the damage evolution laws of coal samples during stressing35,36. DC is a normalized parameter ranging from 0 (indicating no damage) to 1 (representing complete failure).

The damage contribution of coal samples under varying immersion heights is shown in Fig. 9. For unsoaked and 25 mm immersion height samples, the DC shows an “initial increase followed by decline” pattern with the progressive cyclic loading-unloading. In contrast, 50 mm and 75 mm immersion height samples demonstrate continuously increasing DC throughout cycling. This implies water-induced degradation reduces load-bearing capacity, rendering samples increasingly susceptible to damage.

Cumulative irreversible strain corresponds to the total permanent deformation progressively accumulated during successive loading-unloading cycles. As shown in Fig. 10, the cumulative irreversible strain exhibits a positive correlation with immersion height, where the curve slope quantifies the rate of irreversible strain accumulation. The final loading cycle in each immersion height test exhibits the highest rate of irreversible strain accumulation, demonstrating that accelerate damage precipitates structural failure in coal samples.

Energy evolution characteristics

Analyzing energy evolution during stressing enables deeper insights into internal energy accumulation and release process in coal under stress, which can help elucidate the mechanisms of damage accumulation and microcrack propagation.

As shown in Fig. 11a, the total input energy of the coal samples under different immersion heights exhibits comparable trends. Within each stress step, the total input energy progressively declines with increasing cycle count. Furthermore, first-cycle total input energy rises incrementally with ascending stress levels. Notably, unsoaked and 25 mm immersion height samples persistently demonstrate elevated total input energy, suggesting reduced damage accumulation and superior energy absorption capacity under these conditions.

As shown in Figs. 11b and c, the elastic energy and dissipated energy for coal samples under different immersion heights display similar trends. The elastic energy mirrors the trend of total input energy and consistently exceeds the dissipated energy magnitude. This indicates that elastic deformation is the primary form of energy storage during cyclic loading-unloading, with coal samples immersed at 25 mm and unsoaked samples showing higher elastic energy, reflecting better structural integrity and energy storage capacity. The dissipated energy shows little change in magnitude as the number of cycles increases and remains relatively low, indicating that elastic deformation dominates the energy storage throughout the loading-unloading process.

T2 relaxation time evolution characteristics

In NMR T2 spectra, the signal amplitude represents the intensity of the NMR signal, which is related to hydrogen proton density across different pore scales in the coal samples37. Specifically, the amplitude quantifies water content within specific pore size ranges. The T2 spectra of coal samples at different immersion heights showed a “bimodal” distribution, with peaks localized at the range of 0.1–1ms(short relaxation time) and around 10ms, (long relaxation time). The peak of short relaxation time (0.1–1ms) usually corresponds to the water content in small pores, while the peak of long relaxation time (10ms) reflects the water content in large pores. As can be seen from Fig. 12, the peak of the short relaxation time is larger, which indicates that the micropores account for a higher percentage inside the coal samples. With the increase of the immersion height, the peak value of the long relaxation time gradually increases, which indicates that the pore size of the micropores gradually increases and expands to form medium and large pores.

Pore size evolution characteristics

The classification method proposed by Ходот B.В. is commonly used to study the internal pore characteristics of coal38. Based on this method, pores with diameters between 0 and 100 nm are classified as micropores, those between 100 and 1000 nm as mesopores, and those larger than 1000 nm as macropores and microfractures. The pore size distribution of coal samples under different immersion heights is shown in Fig. 13. The results indicate that micropores dominate the pore structure in all coal samples. As the immersion height increases, the proportion of micropores decreases and stabilizes, while the number of mesopores increases. When the immersion height exceeds 25 mm, a small number of macropores and microfractures begin to form in the immersed coal samples. When the immersion height exceeds 50 mm, further structural damage occurs, leading to the formation of macropores and microfractures. These observations demonstrate water infiltration progressively degrades pore architecture by enlarging and interconnecting micropores into mesopores and macropores, with severe structural collapse occurring beyond 50 mm immersion height.

The compaction strengthening—damage softening competitive mechanism

Previous studies have predominantly investigated water-saturated coal failure mechanisms under uniaxial compression, emphasizing the reduction in mechanical strength caused by water. While these findings are critical for explaining water degradation effects, static loading conditions typically involve low loading rates where inertial effects are neglected39. However, dynamic loading scenarios (e.g., mining disturbances) exhibit fundamentally different damage mechanisms, particularly when coupled with water infiltration. Among various loading modes, cyclic loading-unloading represents a critical engineering condition where crack initiation-propagation progressively degrades coal’s mechanical properties, ultimately leading to structural failure. Understanding these processes is therefore essential for ensuring coal structure stability40.

As shown in Fig. 14, the water immersion process of coal samples is divided into three stages: low immersion height, medium immersion height, and high immersion height. At low immersion heights, the contact area between the coal and water is small, resulting in minimal degradation effects on the coal. At this stage, water infiltration into the coal sample occurs slowly, with limited damage. Combining the NMR results from Sect. 3.4.1 and 3.4.2, the infiltration of water molecules causes the formation of micropores at the base of the coal sample. When an external load is applied, the compaction stage of the stress-strain curve (Fig. 5) is prolonged, enhancing the load-bearing capacity of the coal. This confirms the previous observation in Sect. 3.1 that the compaction stage is longest for coal samples immersed at 25 mm. In this stage, water strengthens the coal sample, and brittle deformation is the dominant failure mode, reflecting the “compaction strengthening” effect of water.

As the immersion height increases, the contact area between the coal and water grows, allowing more water molecules to penetrate the coal. Hydrophilic materials within the coal undergo physicochemical interactions with water, leading to phenomena such as displacement, dissolution, and ion exchange. The microstructure of the coal changes, with internal particles becoming smoother and reducing the friction coefficient, which in turn lowers the adhesion strength between particles and reduces the resistance to crack propagation41. The NMR results in Sect. 3.4.2 show that the pore structure evolves, with micropores expanding and connecting to form mesopores and macropores. Microstructurally, this manifests as the generation of numerous micropores and the appearance of macropores. The coal sample begins to accumulate damage.

When a significant portion of the coal sample is submerged, a large number of macropores and microcracks develop. In addition to the above phenomena, compressive stress exerted externally causes further compaction of internal pores, while the expansive effect of water increases the internal stress of the coal, leading to an increase in pore water pressure. According to the effective stress principle (Eq. 8), the increase in pore water pressure causes the effective stresses in the coal sample (the stresses that carry the skeleton of the coal) to decline, which in turn causes the internal structural strength of the coal body to decrease.

where \(\:{\sigma\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the effective stress, Pa; \(\:\sigma\:\) is the total stress, Pa; and \(\:u\) is the pore water pressure, Pa.

Meanwhile, according to the Moore-Cullen damage criterion42 (Eq. 9), when the pore water pressure increases, the shear strength of the coal body is reduced due to the decrease in the effective positive stress, which makes the coal more susceptible to slip or destabilisation along the weak surfaces43 (e.g., laminar and fissure surfaces).

where \(\:\tau\:\) is the shear stress, Pa; \(\:c\) is the cohesive force, Pa; \(\:{\sigma\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the effective positive stress, Pa; \(\:\varnothing\:\) is the friction angle, °.

This stage reflects the degradation of coal’s mechanical properties, with ductile deformation becoming the dominant failure mode. Based on these observations, this study proposes the competitive mechanism of “compaction strengthening - damage softening” due to water immersion.

The revealed “compaction strengthening-damage softening” mechanism offers theoretical insights for adaptive safety management of coal pillar dams. Under low water immersion conditions, localized moisture infiltration may temporarily enhance deformation resistance by densifying the coal’s microstructure. This phenomenon suggests that controlled water injection strategies could be designed to activate self-reinforcing potential in specific zones, guided by real-time monitoring systems tracking moisture distribution—particularly beneficial for stabilizing coal pillars in shallow aquiferous roadways. Conversely, under high immersion scenarios, water-rock interaction-driven damage accumulation progressively compromises structural integrity, necessitating focused monitoring of immersion boundary expansion and risk-aware reinforcement planning to prevent sudden failures44.

A lifecycle “warning-response” management framework is proposed based on the phased characteristics of the mechanism. In low-risk stages, the self-reinforcing properties of coal can be leveraged through periodic inspections and localized humidity control. For medium-to-high-risk stages, an adaptive protection system should be implemented, including hydrophobic barriers to decelerate water ingress in active zones and non-destructive techniques to detect early damage signals, enabling tiered mitigation actions. This approach prioritizes “preventive monitoring and dynamic intervention,” balancing safety requirements with cost efficiency.

Conclusions

This study systematically investigated water-induced damage mechanisms in coal under varying immersion heights through cyclic loading-unloading tests coupled with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis. Three key aspects were explored: mechanical parameter evolution, energy transformation characteristics, and pore structure modification. The revealed “compaction strengthening–damage softening” mechanism demonstrates immersion-height-dependent water effects on coal behavior. Key findings include:

-

(1)

After immersion, coal samples exhibit stress fluctuations after reaching the peak load, with multiple stress rises and drops, reflecting ductile behavior. The peak load increases slightly and then decrease as immersion height increases. Cumulative irreversible strain also increases with immersion height due to damage accumulation. Both LM and UM at different immersion heights show a “rising-declining” trend within the step unit, and by analysing the LURR, irreversible deformation mainly occurs in the later cycles of each step unit. The evolution of elastic strain energy follows the same trend as total input energy and remains higher than dissipated energy throughout the loading-unloading process.

-

(2)

The T2 spectra of coal samples at different immersion heights exhibit a “bimodal” distribution, with peaks located around 0.1–1 ms and 10 ms. As immersion height increases, the amplitude and area of the T2 spectra gradually increase, indicating that water infiltrates and damages the coal pore structure. The pore structure of coal samples is primarily composed of micropores. As immersion height increases, micropores expand into mesopores and macropores, with higher immersion heights showing more pronounced damage.

-

(3)

At low immersion heights, small pores form in the coal sample, prolonging the compaction stage and enhancing the load-bearing capacity, reflecting the “compaction strengthening” effect of water. When the immersion height is large, on the one hand, the physiochemical interaction between coal and water leads to the creation of mesopores and macropores inside the coal samples. On the other hand, the pore water pressure of the coal sample increases, which makes its internal structural strength and shear strength decrease. This is manifested as the damage softening effect of water on the coal sample.

The findings emphasize the profound impact of hydro-mechanical coupling on the long-term stability of coal pillar dams, particularly under water immersion height-dependent damage mechanisms. While this study systematically revealed how immersion height governs coal degradation, practical mining environments face multifaceted challenges from coupled thermal-hydro-mechanical-chemical interactions involving water temperature, immersion duration, hydrodynamic pressure, and cyclic stresses. Future research should prioritize quantifying these multiphysics synergies to establish multiscale damage ontology models that integrate real-time IoT-based monitoring, machine learning-driven instability prediction, and hydro-mechanical coupling simulations. By translating mechanistic insights into engineering logic—such as designing gradient-reinforced layers and intelligent drainage systems—a predictive stability assessment framework can be developed, advancing from empirical practices to data-driven health diagnostics. This approach aims to construct adaptive risk mitigation strategies for deep mining, where dynamic conditions demand intelligent decision-making systems that harmonize theoretical rigor with operational resilience.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.

References

Zou, Q. L. et al. Mesomechanical weakening mechanism of coal modified by nanofluids with disparately sized SiO2 nanoparticles. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 188, 106056 (2025).

Zou, Q. L. et al. Evaluation and intelligent deployment of coal and coalbed methane coupling coordinated exploitation based on bayesian network and cuckoo search. Int. J. Min. Sci. Tech. 32(6), 1315–1328 (2022).

Sahu, P., Lopez, D. L. & Stoertz, M. W. Using time series analysis of coal mine hydrographs to estimate mine storage, retention time, and mine-pool interconnection. Mine Water Environ. 28(3), 194–205 (2009).

Wu, Y. et al. Strength damage and acoustic emission characteristics of water-bearing coal pillar dam samples from Shangwan mine, China. Energies 16(4), 1692 (2023).

Liu, X. S. et al. Study on deformation and fracture evolution of underground reservoir coal pillar dam under different mining conditions. Geofluids, 2186698 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Creep characteristics and long-term strength of underground water reservoirs’ coal pillar dam specimens under different osmotic pressures. J. Clean. Prod. 452, 141901 (2024).

Wang, F. T. et al. Failure evolution mechanism of coal pillar dams in complex stress environment. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 36 (6), 1145–1152 (2019).

Wang, F. T., Liang, N. N. & Li, G. Damage and failure evolution mechanism for coal pillar dams affected by water immersion in underground reservoirs. Geofluids, 2985691 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Coupling influence of inclination angle and moisture content on mechanical properties and microcrack fracture of coal specimens. Lithosphere, : 6226445 (2021). (2021).

Dyke, C. & Dobereiner, L. Evaluating the strength and deformability of sandstones. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 24(1), 123–134 (1991).

Lyu, X., Chi, X. L. & Yang, K. at al. Strength modeling and experimental study of coal pillar-artificial dam combination after wetting cycles. J. Mater. Res. Technol-JMRT, 25: 3050–3060 (2023).

Yu, L. Q. et al. Mechanical and micro-structural damage mechanisms of coal samples treated with dry-wet cycles. Eng. Geol. 304, 106637 (2022).

Tang, C. J. et al. Mechanical failure modes and fractal characteristics of coal samples under repeated drying-saturation conditions. Nat. Resour. Res. 30 (6), 4439–4456 (2021).

Hashiba, K. & Fukui, K. Effect of water on the deformation and failure of rock in uniaxial tension. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 48(5), 1751–1761 (2015).

Zhou, K. Y. et al. Mechanical behavior of sandstones under water-rock interactions. Geomech. Eng. 29 (6), 627–643 (2022).

Vasarhelyi, B. & Van, P. Influence of water content on the strength of rock. Eng. Geol. 84 (1–2), 70–74 (2006).

Li, D. Y. et al. Influence of water content and anisotropy on the strength and deformability of low porosity meta-sedimentary rocks under triaxial compression. Eng. Geol. 126, 46–66 (2012).

Ozdemir, E. & Sarici, D. E. Combined effect of loading rate and water content on mechanical behavior of natural stones. J. Min. Sci. 54 (6), 931–937 (2018).

Chen, T. et al. Effects of water intrusion and loading rate on mechanical properties of and crack propagation in coal-rock combinations. J. Cent. South. Univ. 24 (2), 423–431 (2017).

Teng, T. & Gong, P. Experimental and theoretical study on the compression characteristics of dry/water-saturated sandstone under different deformation rates. Arab. J. Geosci., 13(13) (2020).

Han, P. H., Zhang, C. & Wang, W. Failure analysis of coal pillars and gateroads in Longwall faces under the mining-water invasion coupling effect. Eng. Fail. Anal. 131, 105912 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. A study on the development and evolution of fractures in the coal pillar dams of underground reservoirs in coal mines and their optimum size. Processes 11 (6), 1677 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. The progressive failure mechanism for coal pillars under the coupling of mining stress and water immersion in underground reservoirs. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ., 82(4) (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. A review of stability of dam structures in coal mine underground reservoirs. Water 16 (13), 1856 (2024).

Wang, M. & Wan, W. A new empirical formula for evaluating uniaxial compressive strength using the Schmidt hammer test. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104094 (2019).

Lu, Z. et al. Numerical analysis on the factors affecting post-peak characteristics of coal under uniaxial compression. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 11, 2 (2024).

Zou, Q. L., Hu, Y. L. & Zhou, X. L. Performance of metal circular tube under different loading amplitudes and dynamic resistance-yielding mechanism. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 108913 (2024).

Cao, Z. Z. et al. Fracture propagation and pore pressure evolution characteristics induced by hydraulic and pneumatic fracturing of coal. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 9992 (2024).

Liang, Y. P. et al. Experimental study of mechanical behaviors and failure characteristics of coal under true triaxial cyclic loading and unloading and stress rotation. Nat. Resour. Res. 31 (2), 971–991 (2022).

Wang, H. & Miao, S. J. Energy evolution mechanism and confining pressure effect of granite under triaxial loading-unloading cycle. International Conference on Smart Engineering MaterialsICSEM 362: 012018(2018). (2018).

Liang, Y. P. et al. Effect of strain rate on mechanical response and failure characteristics of horizontal bedded coal under quasi-static loading. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 9 (1), 52 (2023).

Sun, X. M. et al. Study on the microscopic mechanism of strength softening and multiple fractal characteristics of coal specimens under different water saturation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (10), 388 (2023).

Maruvanchery, V. & Kim, E. Effects of water on rock fracture properties: Studies of mode I fracture toughness, crack propagation velocity, and consumed energy in calcite-cemented sandstone. Geomech. Eng. 17 (1), 57–67 (2019).

Xie, H. X., Li, X. H. & Shan, C. H. Study on the damage mechanism and energy evolution characteristics of water-bearing coal samples under cyclic loading. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56 (2), 1367–1385 (2023).

Ran, Q. C. et al. Deterioration mechanisms of coal mechanical properties under uniaxial multi-level cyclic loading considering initial damage effects. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 186, 105941 (2025).

Wang, M. et al. A calibration framework for the microparameters of the DEM model using the improved PSO algorithm. Adv. Powder Technol. 32, 358–369 (2021).

Bi, J. et al. Analysis of the microscopic evolution of rock damage based on real-time nuclear magnetic resonance. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56 (5), 3399–3411 (2023).

Ходот, B. В., Song, S. & Wang, Y. Coal and Gas Outburst (China Industry, 1966).

Zhang, M. Study on the Damage Evolution Law of Pore and Fracture Structure of Coal Under Liquid Nitrogen freeze-thaw and the Mechanism of Permeability Enhancing (Liaoning Technical University, 2021).

Ran, Q. C. et al. Hardening-damage evolutionary mechanism of sandstone under multi-level cyclic loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 307, 110291 (2024).

Yao, Q. L. et al. Influence of moisture on crack propagation in coal and its failure modes. Eng. Geol. 258, 105156 (2019).

Wang, M., Wan, W. & Zhao, Y. L. Experimental study on crack propagation and coalescence of rock-like materials with two pre-existing fissures under biaxial compression. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79 (6), 3121–3144 (2020).

Cao, Z. Z. et al. Experimental study on the fracture surface morphological characteristics and permeability characteristics of sandstones with different particle sizes. Energy Sci. Eng. 12 (7), 2798–2809 (2024).

Cao, Z. Z. et al. Abnormal ore pressure mechanism of working face under the influence of overlying concentrated coal pillar. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 626 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the Open Fund of State Key Laboratory of Water Resource Protection and Utilization in Coal Mining (Grant No. GJNY-20-113-01); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.52404109), which are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X. and H.Y. processed the data and wrote the main manuscript text.Z.Y. , K.F. and W.W. prepared all the figures.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work. We declare that we do not have any commercial or associated interests that represent conflicts of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Hu, Y., Zhang, Y. et al. Effect of immersion height on coal mechanical properties and the mechanism of damage failure. Sci Rep 15, 18153 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97158-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97158-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Stress distribution characteristics of overburden strata during thick coal seam top coal caving

Scientific Reports (2025)