Abstract

The advancement of deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) has resulted in remarkable achievements in image super-resolution methods utilizing CNNs. However, these methods have been limited by a narrow perceptual field and often require a high number of parameters and computational complexity, making them unsuitable for resource-constrained devices. Recently, the Transformer architecture has shown significant potential in image super-resolution due to its ability to perceive global features. Yet, the quadratic computational complexity of self-attention mechanisms in these Transformer-based methods leads to substantial computational and parameter overhead, limiting their practical application. To address these challenges, we introduce the Dual Branch Attention Network (DBAN), a novel Transformer model that integrates prior knowledge from traditional dictionary learning with the global feature perception capabilities of Transformers, enabling image super-resolution. Our model features a ”token dictionary” mechanism that uses auxiliary labeling to provide external prior information, enhancing cross-attention and self-attention computations while maintaining a linear relationship between computational complexity and image size. We also propose a Feature Aggregation Module (FAM) that efficiently extracts local contextual information and performs channel feature fusion, substantially enhancing the model’s performance and efficiency. By reasonably arranging the number of modules and the depth of the network, we reduce the complexity of the model. Extensive experiments have demonstrated that our DBAN achieves excellent performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Image super-resolution reconstruction technology, commonly referred to as ISR, is utilized to enhance the details of low-resolution (LR) images and produce high-resolution (HR) outputs. It significantly elevates the visual quality and intricacy of images. This technology not only elevates the clarity of images but also assists us in overcoming the technical constraints of outdated equipment, thereby enabling them to generate higher-quality image outputs. The application of ISR technology is pivotal in the realm of medical imaging1. It aids doctors in diagnosing diseases with greater precision by elevating image resolution, particularly in X-rays, MRI2, and CT scans, where superior resolution signifies the ability to discern more minute lesions and structures. Furthermore, ISR technology holds significant importance in remote sensing, as it amplifies the resolution of satellite imagery, facilitating enhanced monitoring of land use changes, environmental shifts, and crop growth. Video surveillance stands as another significant application area for ISR technology. By elevating the resolution of images captured by surveillance cameras, it enables more efficient safety monitoring, traffic supervision, and public safety management. The digital entertainment industry, particularly in sectors such as animation, gaming, and film production, benefits significantly from ISR technology. This technology enhances visual effects and significantly improves the user experience. Researchers have proposed various methods to achieve ISR, mainly categorized into three types: interpolation-based methods3, reconstruction-based methods4, and learning-based methods5. Interpolation-based methods estimate high-frequency details of images using mathematical algorithms, such as nearest neighbor interpolation, bilinear interpolation, and bicubic interpolation. Reconstruction-based strategies involve establishing a degradation model for the image and utilizing prior knowledge to restore its details. Learning-based techniques, especially the latest progress in deep learning, train models to grasp the mapping relationship between LR and HR images, thus accomplishing super-resolution reconstruction.

A comparison of model complexity and performance between our proposed DBAN model and other techniques on the Urban100 dataset for \(\times\)4 super-resolution. The circle size indicates the computational complexity in terms of floating-point operations. Our approach offers a more favorable balance between model intricacy and reconstruction performance.

Over the past few years, the swift advancement of hardware technology has empowered the training of deep learning-based super-resolution (SR) methods, like CNNs6,7,8, on extensive datasets. However, these convolutional networks focus solely on modeling local feature dependencies, neglecting the critical establishment of global dependencies, which significantly hinders model performance. As an illustrative case, the Enhanced Deep Residual Networks (EDSR)9, despite its optimization of the conventional CNN architecture—specifically, by eliminating the batch normalization layer and employing residual learning—still possesses a large number of parameters totaling 43 million. This not only amplifies the model’s complexity but also leads to a notably prolonged processing time for a single image, approximately 0.5 s under identical hardware conditions. Such latency is impractical for real-time applications. Additionally, the performance of Transformers10,11,12,13 has consistently outperformed that of convolutional neural networks in various low-level visual tasks. The essence of the Transformer’s superiority is attributed to its self-attention (SA) mechanism14,15,16,17,18,19,20, which facilitates the creation of global dependencies. This capability counters the inherent drawbacks in CNN-based approaches, highlighting the importance of global feature interaction for high-quality image reconstruction. Despite the recent progress in image super-resolution, challenges persist. Transformer-based21,22,23,24 approaches feature self-attention mechanisms that entail a quadratic level of computational complexity, including SwinIR25, necessitates a trade-off between achieving optimal SR accuracy and controlling computational expenses. To manage computational load, previous methods have limited attention computation to local windows. For instance, SwinIR25 employs a \(7\times 7\) local window, reducing computational complexity but concurrently restricting the receptive field, which in turn affects the SR performance. The Omni Aggregation Network (OAN)26 was introduced to enhance SR performance through multi-scale feature fusion within a fully aggregated network framework. However, OAN26 still faces constraints due to the local window attention mechanism, resulting in suboptimal handling of long-distance dependencies. Although OAN26 improves performance through multi-level feature aggregation, it does not entirely surmount the limitations that local windows impose on receptive fields, which in turn affects the overall effectiveness of SR. Studies have revealed that expanding the window size can widen the receptive field and enhance SR outcomes, but this also amplifies the challenges associated with high dimensionality. This situation emphasizes the requirement for a strategy that can model long-range dependencies efficiently, transcending the limitations of local windows. Furthermore, traditional SR methodologies for images typically rely on generic algorithms that do not adapt to the specific characteristics of individual images. Segmenting images based on their content categories, rather than rectangular local window partitioning strategies, may be more advantageous for the SR process and could lead to higher-quality image reconstruction.

Fueled by the insights gained from previous challenges, we present DBAN as a solution for image super-resolution. In the conceptualization of DBAN, we have embraced the fundamental principles of classical dictionary learning27 and applied them to the field of super-resolution, introducing an innovative mechanism termed the “token dictionary.” This mechanism is designed to enhance cross-attention and self-attention computations within image processing and is distinguished by three significant features. Firstly, the token dictionary acquires a suite of auxiliary tokens that encapsulate common image structures, and by employing a cross-attention mechanism, it seamlessly integrates external prior knowledge into the image processing pipeline. This strategy ensures efficient processing, preserving a linear correlation between computational complexity and the scale of the image. Secondly, the token dictionary leverages global information to refine its content by selectively activating specific tokens. It also establishes long-range connections by distilling specific image information through a reverse attention mechanism, which is crucial for capturing long-distance dependencies within the image. Lastly, the token dictionary transcends the limitations of local window segmentation by enabling the use of all analogous image segments to enhance labeling. This is achieved through category self-attention computations that capitalize on the similarities between images and dictionary labels, thereby more effectively preserving and amplifying the structural information inherent in images. Beyond the Transformer block, the feed-forward network (FFN28) operates to capture features utilizing a dense layer. Nonetheless, this network fails to consider spatial details in its feature extraction process. To address this shortcoming, we have developed a spatial gating feedforward network (SGFN). This innovative network incorporates a spatial gate (SG) module within the sequence of two dense layers that constitute the FFN28. The SG module functions as a straightforward regulatory element, leveraging deep convolution alongside element-wise multiplication to refine the input features. The SG module operates by segmenting the input features into two distinct parts along the channel axis, which allows for individual convolution and multiplication processes. By doing so, the SG module enhances the FFN with further nonlinear characteristics that are spatially aware, thereby mitigating the issue of redundant channels. This integration of spatial awareness into the FFN28 through the SGFN leads to a more nuanced and effective feature extraction process. With the aid of SGFN, the Triple Attention Block (TAB) facilitates feature aggregation within the block. Concurrently, drawing inspiration from SAFMN29, we have designed a convolutional module for feature extraction that can dynamically select the most representative features. In summary, we found that DBAN achieves a superior balance between model complexity and super-resolution performance, as depicted in Fig. 1. Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

We have designed a novel dual-branch multi-task and efficient image SR model, DBAN. Our DBAN aggregates features within blocks and between branches to achieve strong representation capabilities.

-

We introduce the concept of dictionary learning, which provides prior information for each image label through a set of auxiliary labels, and effectively summarizes the feature information of the entire image through a set of parallel cross-attention modules and a spatial gating feed-forward mechanism. Moreover, we introduce a FAM module designed to concurrently extract local contextual information and carry out channel feature fusion.

-

We carried out both quantitative and qualitative assessments of the proposed method using benchmark datasets. The outcomes showed that our DBAN not only effectively balances accuracy with model complexity, but also attains state-of-the-art performance in terms of both reconstruction accuracy and visual quality.

Related work

Image super-resolution based on deep learning

Deep convolution-based methods have historically played a pivotal role in ISR. More recent advancements have focused on feature extraction and fusion techniques to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of single image super-resolution (SISR) models. As an illustration, PF-OA30 offers a state-of-the-art technique employing both 1D and 2D convolutional kernels to derive orientation-aware characteristics. It employs a channel attention mechanism to adaptively choose the most informative features. This progressive feature fusion scheme effectively integrates hierarchical features, resulting in a compact yet potent CNN-based model designed for high-quality SISR. Meanwhile, DiVANet31 introduces a directional variance attention mechanism aimed at capturing long-range spatial dependencies and simultaneously exploiting inter-channel dependencies for more discriminative feature representations. The novel incorporation of attention mechanisms alongside residual blocks in DiVANet31 enhances the preservation of finer details, showcasing its superiority over state-of-the-art models in terms of both restoration accuracy and computational efficiency. HCANet32 achieves superior feature extraction through capturing long-range dependencies and neighborhood spectral correlations. PlainUSR33 achieved a 2.9-fold speedup without compromising performance by utilizing reparameterized MBconv blocks.

Vision transformer

Inspired by the success of vision transformers (ViT)34,35,36 in diverse advanced visual challenges, researchers are now delving into the application of Transformer-based models for basic visual tasks. In the field of ISR, these methods have surpassed CNN-based models. For example, SwinIR25 retains the architecture of the Swin Transformer37, utilizing spatial window self-attention and shift operations. ELAN38 employs grouped multi-scale self-attention, while ART39 and OmniSR40 utilize sparse attention, and GRL41 uses anchored self-attention–all strategies aimed at expanding the receptive field and achieving better results. SSR42 segments the image into non-overlapping small blocks, employs a pyramid structure to identify blocks of interest across various scales, and exclusively reconstructs deep features for these designated blocks. This trend indicates that Transformer-based methods are increasingly supplanting CNN-based methods in the image domain, continually enhancing the performance of ISR. Nevertheless, owing to the intrinsic computational complexity of self-attention mechanisms, these Transformer-based methods incur significant computational and parameter overheads. Moreover, they require a large amount of training data to reach peak performance. This presents a significant constraint in practical application scenarios, especially when resources are scarce, thus posing a considerable limitation in such contexts.

Method

In this section, we first describe the SR problem and subsequently present the architecture of our proposed method. After that, we delve into the specific details of the core components that constitute DBAN.

Method description

Image super-resolution involves reconstructing corresponding HR images from LR images. In this context, we define LR images as \(I_x\), typically obtained through the following degradation:

where \(I_y\) represents the HR image before degradation, and \(H(\cdot )\) represents the degradation mapping function. \(I_y\) maps to LR image \(I_x\) through the degradation process, \(\delta\) is a parameter of the degradation process,which generally encompasses factors such as scaling and noise. Usually, only degraded LR images \(I_x\) are provided in SR tasks where the degradation mapping function is unknown. And it may also be affected by factors such as sensor noise, anisotropic degradation, compression artifacts, and speckle noise under different real-world conditions. To simplify this degradation mapping model, most SR algorithms simply represent it as a single downsampling process. It is defined as \(\downarrow s\) (i.e., downsampling operation with a scaling factor of s), as follows:

where \(I_y \otimes k\) represents convolution with fuzzy kernel k. Usually, most datasets utilized in SR tasks employ the aforementioned simplified degradation model to construct LR images. These datasets utilize common bicubic interpolation downsampling operations and anti-aliasing techniques to generate LR and HR pairs, making them suitable for training sets and general benchmark datasets.

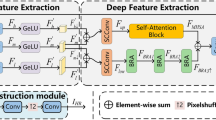

Overall architecture

As depicted in Fig. 2, the proposed DBAN architecture mainly includes four sections: a module for extracting shallow features, another for deep feature extraction, a feature aggregation component, and a module for reconstructing HR images. We will define \(I_x \in R^{h\times w\times 3}\) as the input LR image, where h and w are the height and width of the image, 3 represents the channel dimension of the image. Therefore, \(H_{LF}(I_x)\) represents the shallow feature extraction module, which includes a \(3\times 3\) convolutional layer to extract shallow features \(F_{LF} \in R^{h\times w\times c}\) (c represents the feature dimension after the convolutional layer), \(H_{LF}(\cdot )\) uses the convolutional layer to map the input LR image to a higher dimensional feature space.

Subsequently, the shallow features \(F_{LF}\) are processed by the deep feature extraction module to obtain the deep features \(F_{DF1} \in {R}^{h \times w \times c}\). This module is composed of multiple residual groups (RGs) stacked together, totaling \(N_2\). Additionally, to ensure training stability, a residual strategy is employed within the module. Each RG comprises \(N_1\) triple attention blocks (TABs). At the same time, shallow features are fed into FAM for feature fusion \(F_{DF2} \in {R}^{h \times w \times c}\), and then the final deep features \(F_{DF}\) are obtained by fusing the features of the two branches \(F_{DF1}\) and \(F_{DF2}\).

Finally, we reconstruct the HR output image \(I_{HR} \in {R}^{H_{out} \times W_{out} \times 3}\) through the reconstruction module, where \(H_{out}\) is the height of the output image and \(W_{out}\) represents the width of the output image. In this module, the DySample43 method is utilized for upsampling the deep features. Convolutional layers are utilized to gather features prior to and following upsampling.

where \(H_{RC}(\cdot )\) represents the reconstruction module.

Triple attention module

Token dictionary cross global attention

Within this section, we provide an in-depth look at our newly proposed token dictionary cross global attention block, as depicted in Fig. 3. In contrast to conventional multi-head self-attention (MSA) mechanisms that generate queries, keys, and values based on the input features themselves. Our goal is to initialize an additional dictionary as a grid parameter to introduce external query priors during the training phase. In traditional dictionary-based cross-attention methods, QueryToken mainly relies on the global information of input feature X. However, local features also contain a large amount of detailed information, that is particularly important for SR tasks. We extract local features through convolution operation before generating query tokens, and integrate them with global features to more effectively leverage both local and global information, thereby enhancing the model’s performance. Specifically, before generating the query token \(Q_x\), we first extract local features through convolution operations. Next, we extract global features through global feature extraction operations. Then we use weighted summation operation to fuse local features and global features, generating comprehensive features \(X_{combine}\).

where \(Conv_{3\times 3}\) represents \(3\times 3\) convolution, GlobalPooling represents the global average pooling operation, \(\alpha\) is a learnable parameter used to balance the contributions of local and global features. Finally, we generate query tokens \(Q_X\) using comprehensive features \(X_{combine}\). In order to maintain consistency and integrity, \(K_D\) and \(V_D\) are still generated through dictionaries \(D \in R^{M \times d}\), where M denotes the number of tokens in the dictionary, and d denotes the feature dimension of each token without involving the combination of local and global features.

where \(W_Q \in R^{\frac{d \times d}{r}}\), \(W_K \in R^{\frac{d \times d}{r}}\), \(W_V \in R^{d \times d}\) represent linear transformations for query tokens, key dictionary tokens, and value dictionary tokens, respectively. To maintain lower computational costs, we set \(M<N\). The feature dimension of key dictionary tokens is reduced by a factor of 1/r to decrease model size and complexity, where r denotes the reduction ratio. Subsequently, we utilize the key dictionary and value dictionary to improve query tokens via cross attention computation.

where \(\tau\) is a learnable parameter used to adjust the range of similarity values. Simcos(\(Q_x\), \(K_D\)) represents the cosine similarity between two tokens calculated, the generated similarity graph \(S \in R^{N \times M}\) describes the similarity between the query tokens and the key dictionary token. Where N represents the number of query tokens, and M represents the number of tokens in the dictionary. We use normalized cosine distance instead of dot product operation in MSA because we want every label in the dictionary to have an equal chance of being selected, and similar amplitude normalization operations are common in previous dictionary learning work. And we use the Softmax function to convert the similarity map S into the attention map A for subsequent calculations. Through this approach, our TDCGA is able to embed external priors into the learned dictionary to enhance input image features. We established the layer index (l) for both the input features and the token dictionary. Specifically, \(X^{(l)}\) and \(D^{(l)}\) represent the input features and the token dictionary of the l-th layer.

Spatial window self attention

We put forward a mechanism called Spatial Window Self Attention (SW-SA), which focuses on calculating attention weights within specific windows. As illustrated in Fig. 4b, for the input feature X, its dimension is \(R^{h \times w \times c}\),We first generate query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices through linear transformation. This step can be expressed as:

where \(W_Q, W_K, W_V \in {R}^{c \times c}\) are linear transformation matrixes that do not include bias terms. Next, we divide Q, K, and V into non-overlapping windows and flatten the features within each window into vectors. These flattened vectors are denoted as \(Q_S, K_S, V_S\), with dimensions of \({R}^{H \times W \times C}\). Where \(N_w\) represents the number of feature vector within each window. Then, we divide these vectors into h subsets, each corresponding to an attention head, represented as:

The feature dimensions processed by each head are defined as \(d = \frac{C}{h}\). The illustration in Fig. 4b is the situation with h = 1, where certain details are omitted for simplicity. The output \(Y_s^i\) for the i-th head is defined as:

where B represents the relative position encoding44. Finally, we obtain features \(Y_s\) by reshaping and concatenating \(Y_s^i\), with dimensions of \(R^{h \times w \times c}\), expressed as:

where \(W_P \in R^{c \times c}\) is a linear transformation matrix that integrates the features of all heads together. In addition, to capture richer spatial information, we adopted a shift window mechanism similar to that in Swin Transformer37.

Channel window self attention

We introduce a self-attention mechanism for the channel dimension, called channel window self attention (CW-SA). In this mechanism, we refer to previous research45,46 by dividing the channel into multiple independent heads and performing self-attention operations on each head separately. As shown in Fig. 4a, given input feature X, we first generate query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices through linear transformation, and reshape them to the size of \(R^{hw \times c}\). These reshaped matrices are denoted as \(Q_C\), \(K_C\), and \(V_C\). Similar to spatial window self attention (SW-SA), we divide these projection vectors into h parts, each corresponding to an attention head. To simplify the explanation, Fig. 4 shows the situation when \(h = 1\). For the i-th head, the computation procedure for its channel self-attention can be articulated as:

where \(Y_c^i \in R^{hw \times d}\) represents the output of the i-th head, d represents the dimension of the feature. \(\beta\) is a learnable parameter used to adjust the scale of the inner product before the Softmax function. In the end, we concatenate all \(Y_c^i\) and reshape them to obtain the final attention features \(Y_c = R^{h \times w \times c}\). This process follows the same definition and equation as Eq. (16).

Feature aggregation module

Spatial split feature module (SSFM)

We propose a novel lightweight method aimed at capturing long-range dependencies from multi-scale features to optimize the reconstruction of HR images. As displayed in Fig. 5, we use a feature pyramid network57 to construct attention maps, which are used for spatially adaptive feature adjustment. with the purpose of reducing the complexity of the model and extract multi-scale features, we perform channel segmentation on the standardized input features to obtain four independent parts. Part of it is processed through \(3\times 3\) deep convolution, while the rest is sent to the multi-scale feature generation module. Given the input feature X, the description of this process can be provided by the following formula:

where \(\uparrow _p\) represents upsampling features to the original resolution through nearest neighbor interpolation. \(\downarrow _p\) Denotes downsampling features to the size of \(\frac{p}{2^i}\). In order to filter out features that are helpful for learning non-local interactions, we apply adaptive max pooling on input features to generate multi-scale features. Next, we merge these multi-scale features and integrate local and global information through a \(1\times 1\) convolution:

After acquiring enhanced feature depictions \(\hat{X}\),we standardize the data using the GELU non-linear activation method to determine the focus pattern and modify X in a responsive manner based on the focus pattern.

\(\phi (\cdot )\)represents the GELU function, and the operation \(\otimes\) denotes element-wise multiplication. Leveraging multi-scale feature representation, we can apply this spatial adaptive modulation mechanism to collect remote features with less memory and computational cost. Compared with directly using deep convolution to extract features, this multi-scale form achieves better performance with less memory consumption.

Convolutional channel feature mixer

We note that the first half of the FAM module focuses on exploring global information, while local contextual information is equally important for high-resolution image reconstruction. Unlike conventional feedforward networks, which typically use two consecutive \(1\times 1\) convolutions to transform features and explore local contextual information, we are inspired by FMBConv58 and propose convolutional channel feature mixer (CCFM) to enhance local spatial modeling and perform channel mixing. As shown in Fig. 6, CCFM consists of a \(3\times 3\) convolution and a \(1\times 1\) convolution, where the \(3\times 3\) convolution is used to encode spatial local context and double the number of channels for input features, followed by a \(1\times 1\) convolution to reduce the number of channels back to the original dimension. The GELU function is applied to the hidden layer for nonlinear mapping, which is more memory efficient than using \(3\times 3\) deep convolution (such as inverted residual blocks) on the extended dimension. The FAM module we propose can be represented as:

\(LN(\cdot )\) represent LayerNorm layer, X represents the input feature, and Y denotes the output fused feature.

Experiment

Details of implementation and training

Datasets and evaluation metrics

In this research the DIV2K59 and Flickr2K9 datasets are used as the training sets, as well as five benchmark datasets: Set560, Set1461, B10062, Urban10063, and Manga10964 for testing. Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR65) and Structural Similarity (SSIM66) are used as evaluation metrics in these datasets for model performance assessment. To ensure a fair comparison with other SR techniques, we transform the image from RGB to YCbCr format and subsequently compute the PSNR and SSIM on the Y channel.

Training setting

For DBAN, there are 4 residual groups(RGs), and each RG contains 6 TAB modules. At the same time, there are also 2 FAM modules. We adhere to the majority of prior research in training and testing our model. We train the model using patches of size \(64\times 64\) and a batch size set to 16. Horizontal flipping and random rotations of \(90^\circ\), \(180^\circ\), and \(270^\circ\) are used for data augmentation while model training. We created 64 tokens for the external dictionary D in each TAB block and set the reduction rate \(r=6\). We use the AdamW67 optimizer with \(\beta _1=0.9\) and \(\beta _2=0.9\) to minimize L1 pixel loss estimation between HR and ground truth. The learning rate was initially set to \(2\times 10^{-4}\), and then decreased by half after the 250th, 400th, 450th, and 475th epochs. All training and testing of the model were conducted using PyTorch68 on the RTX 4090 GPU.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

We have compared our model with the current 11 state-of-the-art image super-resolution methods: CARN47, IMDN48, SwinIR-light25, LAPAR-A49, ELAN-light38, SwinIR-NG50, DAT-light51, LKFN52, MDRN53. OSFFNet54 HiT55. Table 1 shows quantitative comparison, while Figs. 7, 8 and 9 provides visual comparison.

Quantitative results

Table 1 shows the results of image SR on \(\times\)2, \(\times\)3, and \(\times\)4 factors. on the Manga109 dataset at a \(\times\)4 scale, our method achieves a PSNR value that is 0.97 dB higher than that of LAPAR-A49. Similarly, in the Urban100 dataset at a \(\times\)3 scale, our method’s PSNR value exceeds that of CARN47 by 0.89dB. Our DBAN outperforms almost all comparison methods on the benchmark dataset in three aspects.

Visual results

As shown in Fig. 7, we provide the visualization comparison results magnified by a factor of \(\times 4\) on the Urban100 dataset. We have presented the visualization comparison results at a \(\times 4\) magnification on the Set14, B100, and Manga109 datasets in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. In contrast, our method distinguishes itself by effectively mitigating these artifacts, which are often attributed to the limitations of conventional upgrading techniques. For instance, in img_020, most comparative methods struggle to restore details and introduce unwanted artifacts. Nevertheless, our DBAN is capable of restoring the correct structure with distinct textures. Similar observations can be made in img_062 and img_076. This is primarily due to our method’s enhanced representational capabilities, stemming from the extraction of complex features from various dimensions.

Ablation study

Feature aggregation module

To illustrate the impact of the feature aggregation module, we conducted an ablation study in Table 2, comparing the results with and without the feature aggregation module at Urban100 scaling factor \(\times\)2. Not using feature aggregation module Compared with the results, using the feature aggregation module increased PSNR by 0.02.

Token dictionary cross global attention

We confirmed its effectiveness by carrying out ablation studies on the cross global attention of the token dictionary. In Table 3, we chose a scaling factor (\(\times 2\)) to assess the performance of token dictionary cross global attention. The results on Urban100 with a scaling factor of (\(\times 2\)) showed that compared to the baseline model, PSNR was increased by 0.07 dB through the addition of token dictionary cross global attention. The ablation experiment shows that the proposed token dictionary cross global attention can improve the the model’s global modeling capability and yield high-quality HR images (Table 4).

The impact of the number of residual groups and attention heads on model performance

We explored the impact of different RGs and the number of attention heads on the final network reconstruction performance through ablation experiments. As shown in Table 5, we set the number of RGs and attention heads to 2, 4, and 6 for training. The final test results of the five benchmark scaling factors of \(\times 2\) indicate that the final reconstruction improves with the increase of residual group and attention head. This confirms that the attention module in the RGs can improve the final network performance, thereby enhancing its ability to model global images. It is evident from the table that the performance of the model improves with the increase of RGs and attention heads. However, in order to balance computational cost and reconstruction performance, we chose RGs = 4 and attention heads = 4 in the final network.

Performance variations with different token dictionary sizes (M)

In our experiments, we investigate the impact of token dictionary size \(M\) on model performance by varying \(M\) from 16 to 96. As shown in Table 6, the results demonstrate that increasing \(M\) initially improves performance, with PSNR and SSIM scores peaking at \(M = 64\) (26.55 and 0.7977 on Urban100; 30.99 and 0.9144 on Manga109). However, further increasing \(M\) to 96 leads to a slight performance degradation, indicating that an excessively large dictionary may exceed the model’s capacity and introduce redundancy. These findings suggest that an optimal token dictionary size exists, balancing expressiveness and computational efficiency.

Model size analysis

To evaluate the model’s efficiency, we compare the number of parameters with several state-of-the-art algorithms. Additionally, we tested the floating-point operations per second (FLOPS) and parameter counts of our model on the same RTX 4090 GPU with a scaling factor of \(\times 2\). In Table 4, our model has roughly half the number of parameters and approximately 55G fewer floating-point operations compared to CARN47, while achieving a 0.16dB higher PSNR on the Manga109 dataset.

Analysis of training time and memory usage

On the RTX 4090 GPU, we simulated 50 rounds of training and 1000 instances of inference with a scaling factor of 4. The optimizer used Adam, and the learning rate was set at \(1\times 10^{-3}\). As shown in Table 7, during the training phase, the average time per epoch was 268.21 ms, with a maximum memory usage of 1936.48 MB. In the inference phase, the average inference time was 45.9 ms, and the maximum memory usage was 56.34 MB. This indicates that our model is efficient in terms of training and inference time, while consuming minimal memory.

Memory and running time comparisons

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of our suggested approach, we conducted a comparison with five representative methods: CARN-M47, CARN47, EDSR-baseline9, IMDN48, and LAPAR-A49. We evaluated GPU memory consumption (#GPU Mem.) and runtime (#Avg. Time) at a \(\times\)4 super-resolution (SR) scale. During inference, we recorded the peak GPU memory consumption. The runtime was calculated as the average over 50 test images, each with a resolution of 320 \(\times\) 180 pixels. Table 8 presents a comparison of our method’s memory usage and runtime with those of the other methods. In terms of memory usage, our DBAN is approximately 20 times larger than IMDN48 and about 9 times larger than EDSR9. However, its running speed is only 6 times that of IMDN48 and 3 times that of EDSR9. Tables 4 and 8 illustrate that the model we have introduced provides an advantageous balance among the speed of inference, the intricacy of the model, and the quality of reconstruction outcomes, compared to state-of-the-art methods.

Conclusion

In this work, we introduce a novel dual-stream multitasking model for efficient image super-resolution. Our model, DBAN, aggregates channel and spatial features through a dual approach of intra-block and inter-block processing, demonstrating robust representation capabilities. Drawing inspiration from traditional dictionary learning methods, we propose a token dictionary cross global attention mechanism that provides external additional information, which helps to enrich any lacking high-quality detail features. Consequently, we not only harness local features but also merge global features, overcoming the constraints of local windows and establishing remote connections between similar structures within the image. Furthermore, we propose modeling global dependencies using spatial window attention and channel window attention, achieving intra-block feature aggregation across both spatial and channel dimensions. In the image reconstruction section, we introduce Dysample to replace the traditional pixelshuffle, aiming for a more lightweight architecture. Extensive experiments have demonstrated that DBAN delivers superior performance with reduced complexity.

Data availibility

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the https://github.com/igotsmoke9/DBAN.

References

Jia, Y., Chen, G. & Chi, H. Retinal fundus image super-resolution based on generative adversarial network guided with vascular structure prior. Sci. Rep. 14, 22786 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Deep learning-based super-resolution and denoising algorithm improves reliability of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in diffuse glioma. Sci. Rep. 14, 25349 (2024).

Liu, Y., Ge, T., Mathews, K. S., Ji, H. & McGuinness, D. L. Exploiting task-oriented resources to learn word embeddings for clinical abbreviation expansion. arXiv: 1804.04225 (2018).

Hoogeboom, E., Peters, J. W., Cohen, T. S. & Welling, M. Hexaconv arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.02108. (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Esrgan: Enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) workshops, 0–0 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Real-world single image super-resolution: A brief review. Inform. Fus. 79, 124–145 (2022).

Wang, P., Bayram, B. & Sertel, E. A comprehensive review on deep learning based remote sensing image super-resolution methods. Earth Sci. Rev. 232, 104110 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Srdiff: single image super-resolution with diffusion probabilistic models. Neurocomputing 479, 47–59 (2022).

Lim, B., Son, S., Kim, H., Nah, S. & Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, pp. 136–144 (2017).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv: 2010.11929 (2020).

Han, D., Pan, X., Han, Y., Song, S. & Huang, G. Flatten transformer: Vision transformer using focused linear attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 5961–5971 (2023).

Vasu, P. K. A., Gabriel, J., Zhu, J., Tuzel, O. & Ranjan, A. Fastvit: A fast hybrid vision transformer using structural reparameterization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 5785–5795 (2023).

Zhou, H.-Y. et al. nnformer: Volumetric medical image segmentation via a 3d transformer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 4036–4045 (2023).

Zhang, H., Goodfellow, I., Metaxas, D. & Odena, A. Self-attention generative adversarial networks. In International conference on machine learning, pp. 7354–7363 (PMLR, 2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Srformer: Permuted self-attention for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 12780–12791 (2023).

Cao, M. et al. Masactrl: Tuning-free mutual self-attention control for consistent image synthesis and editing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 22560–22570 (2023).

Du, X., Jiang, S., Si, Y., Xu, L. & Liu, C. Mixed high-order non-local attention network for single image super-resolution. IEEE Access 9, 49514–49521 (2021).

Talreja, J., Aramvith, S. & Onoye, T. Dhtcun: Deep hybrid transformer CNN U network for single-image super-resolution. IEEE Access (2024).

Du, X., Niu, J. & Liu, C. Expectation-maximization attention cross residual network for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 888–896 (2021).

Han, Y., Du, X. & Yang, Z. Two-stage network for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 880–887 (2021).

Saharia, C. et al. Image super-resolution via iterative refinement. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 4713–4726 (2022).

Lu, Z. et al. Transformer for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 457–466 (2022).

Chen, X., Wang, X., Zhou, J., Qiao, Y. & Dong, C. Activating more pixels in image super-resolution transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 22367–22377 (2023).

Conde, M. V., Choi, U.-J., Burchi, M. & Timofte, R. Swin2sr: Swinv2 transformer for compressed image super-resolution and restoration. In European conference on computer vision, pp. 669–687 (Springer, 2022).

Liang, J. et al. Swinir: Image restoration using swin transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 1833–1844 (2021).

Wang, H., Chen, X., Ni, B., Liu, Y. & Liu, J. Omni aggregation networks for lightweight image super-resolution (2023). arXiv: 2304.10244.

Tariyal, S., Majumdar, A., Singh, R. & Vatsa, M. Deep dictionary learning. IEEE Access 4, 10096–10109 (2016).

Bebis, G. & Georgiopoulos, M. Feed-forward neural networks. IEEE Potentials 13, 27–31 (1994).

Sun, L., Dong, J., Tang, J. & Pan, J. Spatially-adaptive feature modulation for efficient image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 13190–13199 (2023).

He, Z. et al. Single image super-resolution based on progressive fusion of orientation-aware features. Pattern Recogn. 133, 109038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109038 (2023).

Behjati, P. et al. Single image super-resolution based on directional variance attention network. Pattern Recogn. 133, 108997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2022.108997 (2023).

Hu, S., Gao, F., Zhou, X., Dong, J. & Du, Q. Hybrid convolutional and attention network for hyperspectral image denoising. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5 (2024).

Wang, Y., Li, Y., Wang, G. & Liu, X. Plainusr: Chasing faster convnet for efficient super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Asian conference on computer vision, pp. 4262–4279 (2024).

Yuan, L. et al. Tokens-to-token vit: Training vision transformers from scratch on imagenet. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 558–567 (2021).

Yin, H. et al. A-vit: Adaptive tokens for efficient vision transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 10809–10818 (2022).

Bao, F. et al. All are worth words: A vit backbone for diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 22669–22679 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 10012–10022 (2021).

Zhang, X., Zeng, H., Guo, S. & Zhang, L. Efficient long-range attention network for image super-resolution. In European conference on computer vision, pp. 649–667 (Springer, 2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Accurate image restoration with attention retractable transformer. arXiv: 2210.01427 (2022).

Wang, H., Chen, X., Ni, B., Liu, Y. & Liu, J. Omni aggregation networks for lightweight image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/cvf conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 22378–22387 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Efficient and explicit modelling of image hierarchies for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 18278–18289 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Transformer-based selective super-resolution for efficient image refinement. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 38, pp. 7305–7313 (2024).

Liu, W., Lu, H., Fu, H. & Cao, Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 6027–6037 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Crossformer++: A versatile vision transformer hinging on cross-scale attention. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 46(5), 3123–3136 (2023).

Ali, A. et al. Xcit: Cross-covariance image transformers. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 20014–20027 (2021).

Zamir, S. W. et al. Restormer: Efficient transformer for high-resolution image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 5728–5739 (2022).

Ahn, N., Kang, B. & Sohn, K.-A. Fast, accurate, and lightweight super-resolution with cascading residual network. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), pp. 252–268 (2018).

Hui, Z., Gao, X., Yang, Y. & Wang, X. Lightweight image super-resolution with information multi-distillation network. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM international conference on multimedia, pp. 2024–2032 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Lapar: Linearly-assembled pixel-adaptive regression network for single image super-resolution and beyond. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 20343–20355 (2020).

Choi, H., Lee, J. & Yang, J. N-gram in swin transformers for efficient lightweight image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 2071–2081 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Dual aggregation transformer for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 12312–12321 (2023).

Chen, J., Duanmu, C. & Long, H. Large kernel frequency-enhanced network for efficient single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 6317–6326 (2024).

Mao, Y. et al. Multi-level dispersion residual network for efficient image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 1660–1669 (2023).

Wang, Y. & Zhang, T. Osffnet: Omni-stage feature fusion network for lightweight image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, vo. 38, pp. 5660–5668 (2024).

Zhang, X., Zhang, Y. & Yu, F. Hit-sr: Hierarchical transformer for efficient image super-resolution (2024). arXiv: 2407.05878.

Talreja, J., Aramvith, S. & Onoye, T. Dans: Deep attention network for single image super-resolution. IEEE Access 11, 84379–84397 (2023).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 2117–2125 (2017).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnetv2: Smaller models and faster training. In International conference on machine learning, pp. 10096–10106 (PMLR, 2021).

Timofte, R., Agustsson, E., Van Gool, L., Yang, M.-H. & Zhang, L. Ntire 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: Methods and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, pp. 114–125 (2017).

Bevilacqua, M., Roumy, A., Guillemot, C. & Alberi-Morel, M. L. Low-complexity single-image super-resolution based on nonnegative neighbor embedding. (2012).

Zeyde, R., Elad, M. & Protter, M. On single image scale-up using sparse-representations. In Curves and Surfaces: 7th international conference, Avignon, France, June 24-30, 2010, Revised Selected Papers 7, pp. 711–730 (Springer, 2012).

Martin, D., Fowlkes, C., Tal, D. & Malik, J. A database of human segmented natural images and its application to evaluating segmentation algorithms and measuring ecological statistics. In Proceedings eighth IEEE international conference on computer vision. ICCV 2001, vol. 2, pp. 416–423 (IEEE, 2001).

Huang, J.-B., Singh, A. & Ahuja, N. Single image super-resolution from transformed self-exemplars. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 5197–5206 (2015).

Matsui, Y. et al. Sketch-based manga retrieval using manga109 dataset. Multimedia Tools Appl. 76, 21811–21838 (2017).

Hore, A. & Ziou, D. Image quality metrics: PSNR versus SSIM. In 2010 20th international conference on pattern recognition, pp. 2366–2369 (IEEE, 2010).

Wang, S., Rehman, A., Wang, Z., Ma, S. & Gao, W. Ssim-motivated rate-distortion optimization for video coding. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. Video Technol. 22, 516–529 (2011).

Loshchilov, I., Hutter, F. et al. Fixing weight decay regularization in adam. arXiv: 1711.051015 (2017).

Paszke, A. et al. Automatic differentiation in pytorch. (2017).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62401398), in part by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LQ24F020016), in part by the Wenzhou Key Laboratory Construction Project (Grant No. 2022HZSY0048), in part by General Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (Grant No. Y202248776), in part by Wenzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. G20220035), and in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grants No.: LGG22F020040); the Wenzhou scientific research project (Grants No.: ZG2024013), Key Laboratory of Data Intelligence and Governance of Wenzhou City(Grant No. KLDI2025005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Ge, Y., Qi, M. et al. Dual branch attention network for image super-resolution. Sci Rep 15, 29019 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97190-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97190-1