Abstract

Somatostatin (SS) plays an important role in regulating food intake and following digestive functions of vertebrates mediated via somatostatin receptor (SSTR). However, the feedback regulation by which food intake regulate SS and SSTRs expression, and thereby their functions, remains poorly understood. Here, we cloned somatostatin genes (pss1, pss2 and pss3) and somatostatin receptors genes (sstr2a, sstr2b, sstr2c, sstr3a, sstr3b, sstr5a and sstr5b) from tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus and conducted their tissue distribution. Phylogenetic analysis and genomic synteny maps revealed their high homology across the vertebrates and evolution history. Following, synthesized SS-14 and SS-28 were both confirmed to bind to SSTRs and mediated Erk1/2 or Akt phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner and time-course effect in 293T cell line as well as tilapia primary hepatocytes. It was observed that the expression levels of SS family showed dynamic change during food intake. In the early stages of feeding, pss2 expressed in gastric epithelium was down-regulated by food intake, and the following low pH after feeding reversed to up-regulate the pss2 mRNA level. This down and up dynamic change hinted that the first down pss2 prompted food digesting and the next up pss2 inhibited digestion, but it might need further explore to prove. Compared with it, sstr3a expression levels in submucosa up-regulated after feeding but did not display dynamic change. Our results contribute to the understanding of how somatostatin family respond to food intake during different stages of feeding, which provides basis for subsequent study of their function in gastrointestine of tilapia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Somatostatin (SS), a cyclic polypeptide cleaved from precursor-somatostatin (PSS), was first isolated from the ovine hypothalamus and named according to its negative regulation of growth hormone(GH) in 19731. Since the initial discovery, somatostatin has been found as a diverse hormone family verifying in length from 14 to 37 amino acids depending on species2. In teleost, because of genome duplication and other mutant events, at least three precursor-somatostatin coding genes have been identified, including pss1 which is conservative among vertebrates, pss2 which codes teleost-special SS peptide, and pss3 which is similar to mammalian cortistatin (CST)3. Somatostatin is produced in epithelial, neuronal, and immune cells, and approximately 30%, 5%, and 65% of SS are produced in the Central nervous system (CNS), pancreas (or it is known as “Brockmann body” in teleost4), and gastrointestinal5.

SS activates through a multifaceted signal pathway mediated by somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), linked to many different effectors to undertake its biological functions6. SSTRs belong to a seven transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) family, consisting of five subtypes, of which only SSTR1/2/3/5 were found in teleost7. However, the SSTR1/2/3/5 in teleost also have their respective subtypes due to 3R (three round genome duplication, 3R)8. Every SSTR exhibits different distribution, binding affinities, and signal transduction patterns that contribute to many functions of the SS system9.

SS system plays an important role in regulating feeding and gastrointestinal functions. SSs have orexigenic or anorexigenic effects depending on their doses10. Low doses of SS or its agonist injections into the brain improve food intake in mammal and non-mammalian species11. However, injections with higher doses of SS have a contrasting effect in that the food intakes are decreased10. Gastrointestinal SSs were proven as the widely negative regulator. SS system play an inhibiting role in regulating gastrointestinal peptides like cholecystokinin (CCK), ghrelin, gastrin, gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP), motilin, neurotensin, and secretin6. Among them, the SS system has been implicated in the regulation of gastric pH by interaction with gastrin12. In addition, SS inhibits intestinal nutrient absorption (glucose, lipid, and amino acid), accelerates gastric emptying, weakens gallbladder contraction, and prolongs small-intestinal transit time6.

Due to the feedback of the endocrine system, the SS system is also regulated by food intake and other changes brought about by it which process is dynamic. In human, feeding increases plasma SS levels at 60 min and recovers at 180 min post-food intake13,14. In anadromous Coilia nasus, transcriptome reveals that food intake downregulates SS expression levels in the stomach15. On the other hand, the lack of food stimulation also affects the SS and SSTRs expression. In rat colon, 48h fasting increases SS and SSTR expression levels16. In teleost, the mRNA levels of SS are increased by fasting and decreased by refed in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus)17. In juvenile grouper (Epinephelus coioides), 5-days starvation increases the SS-immunoreactive(-ir) cells of the stomach cardiacus and decreases SS-ir cells of the stomach fundus and stomachus pyloricus18. Additionally, decreasing pH due to gastric acid secretion during food intake can participate in the regulation of feeding and fasting on SS. Perfusion with 0.1M HCl causes a large output of SS in dog19. In rat, the gastric cavity must be acidic for somatostatin secretion to respond to the same stimulus in vitro20.

Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is a widely farmed fish with high economic value, therefore, the study of its feeding regulation mechanism is of great significance. The previous studies of SS lack the trace of the SS respond to food intake which is important to understand the role of SS in feeding and digestion. Here, we identified three PSSs and seven SSTRs genes from tilapia. The dynamic changes of SS and SSTR gene expression levels regulated by food intake were explored in vivo. Following, we explored the effects of feeding on pss2 and sstr3a which have high abundance in stomach ex vivo and in vitro. Our results supplement messages of the SS family in vertebrates and provide new evidence of the interaction of SS and food intake.

Result

Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of somatostatin and its receptors from tilapia

We cloned three PSS cDNAs, pss1, pss2 and pss3, and seven somatostatin receptor cDNAs, sstr2a, sstr2b, sstr2c, sstr3a, sstr3b, sstr5a and sstr5b, from tilapia. Sequence messages were submitted to NCBI. (The sequence IDs are as follows. pss1: MW848783.1, pss2: MW848784.1, pss3: MW848785.1, sstr2a: MW848786.1, sstr2b: MW848787.1, sstr3a: MW848788.1, sstr3b: MW848789.1, sstr5a: MW848790.1).

PSS cDNAs were 360 bp, 576 bp, and 333 bp, encoding 119 amino acids(pss1), 191 amino acids(pss2) and 110 amino acids(pss3) respectively. The pss1 encoding protein had a 20 amino acids signal peptide predicted in the N-terminal and 14 amino acids SS-14 in the C-terminal. The pss2 encoding protein had a [Tyr7, Gly10, Leu11] SS-14 in the C-terminal but no predicted signal peptide in the N-terminal. And pss3 encoding protein has an 18 amino acids signal peptide in the N-terminal and a [Pro2] SS-14 in the C-terminal (Fig. 1a).

Sequence analysis and tissue distribution of SSs and SSTRs of tilapia. (a) alignment of SSs. The grey frame represents signal peptide, and special deduced amino acids are marked by red font. (b) alignment of SSTRs deduced amino acid of Nile tilapia, the “*”, “:”, “.” represent the same amino acid, highly conserved and low conserved, respectively. Underline indicates the transmembrane domain of SSTRs. (c) tissue distribution of pss1-3 of tilapia. (d) tissue distribution of sstr2a-5b genes of tilapia. The mRNA levels were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized against 18S gene transcripts. Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3).

Somatostatin receptors cDNAs were 1140 bp, 1113 bp, 1020 bp, 1452 bp, 1449 bp, 1080 bp, and 1170 bp encoding 379 amino acids (sstr2a), 370 amino acids (sstr2b), 339 amino acids (sstr2c), 483 amino acids (sstr3a), 482 amino acids (sstr3b), 359 amino acids (sstr5a) and 389 amino acids (sstr5b) respectively. The amino acid sequence of SSTRs contained seven conserved transmembrane regions (Fig. 1b). Both SSTRs have a YANSCANPIL/VLY motif at the seventh transmembrane segment. In addition, no signal peptide was found in five SSTRs.

To explore the expression pattern of PSSs and SSTRs in CNS and peripheral tissue of tilapia, RT-PCR was used to examine the cDNA from CNS and peripheral tissue. The expression patterns of PSSs and SSTRs were shown in Fig. 1c–d. The pss1 was detected in the forebrain, midbrain, medulla oblongata, and hypothalamus, whereas pss2 was detected with a decreased level in the forebrain, medulla oblongata, and hypothalamus. The pss3 was widely expressed in CNS except pituitary (Fig. 1c). Unlike in CNS, in peripheral tissue, pss2 was higher expressed in the stomach and Brockmann body. The pss1 could only be detected in the pancreas and testis. The pss3 was not found expressed in peripheral tissue (Fig. 1c). All SSTRs were detected widely in CNS (Fig. 1d). The sstr2a, sstr3b, and sstr5b were highest expressed in the forebrain and medulla oblongata respectively, and the sstr2b, sstr3a, and sstr5a were highest expressed in the pituitary. A very different expression pattern between CNS and peripheral tissue could be found in SSTRs too. The sstr3a was detected in some regions of the stomach. Both sstr2a and sstr2b were detected in the liver and only sstr2a was detected in the Brockmann body. In addition, sstr2c, sstr5a, and sstr5b were detected an increasing expression from the anterior segment to the terminal segment of the intestine. Finally, we detected the expression of sstr2a, sstr3a, and sstr5a in Brockmann body. The expressions of multi SSTRs were detected in testis (Fig. 1d).

Phylogenetic tree and genomic synteny analysis on somatostatin system of tilapia

The phylogenetic tree of the PSSs and SSTRs was created using MEGA X to illustrate the phylogenetic relationships of Nile tilapia with other known vertebrates (Fig. 2). As is shown in Fig. 2a, PSSs of previously cloned and newly identified were divided into three clades and the cloned pss1, 2, and 3 of Nile tilapia were counterparts of other vertebrates, including human (Homo sapience), mouse (Mus musculus), frog (Anura spp), chicken (Gallus domesticus) and many different fish species. Moreover, the pss1 clade was clustered at the root of the phylogenetic tree, and pss2 and pss3 were clustered at the branch, which pss2 clade was closer to the pss1 clade than the pss3 clade.

The phylogenetic tree of SSTRs was shown in Fig. 2b. All SSTRs were divided into five clades. The cloned SSTRs of Nile tilapia were counterparts of other vertebrates, including human, mouse, frog, chicken, and many different fish species. The sstr2a and sstr2b of Nile tilapia were clustered into the SSTR2 clade. Such clusters also appeared in sstr3a, sstr3b, sstr5a, and sstr5b of Nile tilapia. Furthermore, sstr2/3/5 were clustered into a clade compared with sstr1/4.

Because the PSSs and SSTRs sequence were too conservated to reveal the evolutionary history of multiple PSSs and SSTRs genes identified in the present study, we further performed genomic synteny analysis (Fig. 3). In Nile tilapia, zebrafish, and rainbow trout, PSS genes were mapped to two chromosomal: pss1 and pss2 were arranged in tandem on the same chromosomal fragment, and pss3 was located in another chromosomal fragment. The pss1 located chromosomal fragment was homologous to the human chr3 and the pss3 localized chromosomal fragment was homologous to human Chr1. The sstr2a and sstr2b of Nile tilapia, zebrafish, and rainbow trout were localized in two homologous chromosomal fragments respectively. The sstr2c was arranged in tandem on the same chromosomal fragment as sstr2a. Both of them were homologous to Chr17 of human, whereas sstr2a localized chromosomal fragments were more conservative among investigated vertebrates. Analogously, sstr3a and sstr3b were localized in different chromosomal fragments homologous to Chr22 of human. The sstr5a or sstr5b of Nile tilapia and zebrafish were located in the same chromosomal fragments with genomic synteny. However, genes adjacent to sstr5a and sstr5b of fish were mapped on different two chromosomes of human (Chr16 and17).

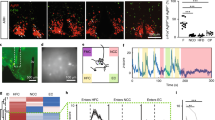

Identification of SSTR biological activity and its mediation of SS ligand on signal phosphorylation

To explore whether the tilapia SSTRs we identified have biological functions, we detected levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation mediated by SSTRs after co-transfection of pcDNA3.1(-)/Zeo-sstr2a/sstr2b/sstr2c/sstr3a/sstr3b/sstr5a/sstr5b, pGL4.33[luc2P/SRE/Hygro] vector containing a serum response element (SRE) and a pRL-TK (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4: SS-14 binding to SSTRs significantly increased the fluorescence of the Erk1/2 signal pathway in a dosage-depend manner. SS-14 took approximately eightfold (sstr2a), 11-fold (sstr2b), 17-fold (sstr3a), threefold (sstr3b) 2.5-fold (sstr5a) and fourfold(sstr5b) improving Erk1/2 level compared with control under 1000 nM treatment, respectively. Similarly, SS-28 binding to SSTRs activated the Erk1/2 signal pathway improving fluorescence level in a dosage-depend manner. However, compared with SS-14, the effect of SS-28 activating the Erk1/2 signal pathway was lower, and the improvements of fluorescence level were 3.5-fold (sstr2a), fourfold (sstr2b),1.5-fold(sstr2c) fivefold (sstr3a), twofold (sstr3b), fivefold (sstr5a) and tenfold(sstr5b) compared with control under 1000 nM.

Identification of SSTRs biological activity in HEK293t cells line. HEK293t cells transfected with pcDNA3.1(-)Zeo/sstr2a/2b/2c/3a/3b/5a/5b were treated with synthetic SS-14 and SS-28. (a–g): the fluorescence of cells expressing SSTR2a, SSTR2b, SSTR2c, SSTR3a, SSTR3b, SSTR5a and SSTR5b treated with SS-14. (h–n): the fluorescence of cells expressing expressing SSTR2a, SSTR2b, SSTR2c, SSTR3a, SSTR3b, SSTR5a and SSTR5b treated with SS-28. Each value represents mean ± S.E.M (n = 4), with asterisks indicating significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, t-test).

To explain the effect of SS-14 and SS-28 on the signal pathways in tilapia primary hepatocytes, time-course and dosage-course studies of SS-14 and SS-28 affecting Erk1/2 and Akt phosphorylation were performed. The results were shown in Fig. 5. The Erk1/2 phosphorylation level was increased significantly at 5 min, 10 min, and 15 min upon 100 nM SS-14 treatment, and subsequently decreased. The Erk1/2 phosphorylation level reached a maximum at 100 nM SS-14 treatment. Nevertheless, SS-14 inactivates phosphorylation of the Akt signal pathway in time-course and dosage-course experiments. Remarkably, compared with SS-14, SS-28 performed a bit difference of effect in Erk1/2 and Akt phosphorylation level: both Erk1/2 and Akt signal pathway were not activated by SS-28 in 100 nM from 5 to 60 min in the time-course study. However, Erk1/2 and Akt phosphorylation levels were significantly promoted to 1.5-fold and twofold in hepatocytes treated by 1000 nM SS-28.

Time-course and dosage-course effect of synthetic SS-14 and SS-28 binding to SSTR actived Erk and Akt phosphorylation in tilapia primary hepatocytes. (a–b): time-course effect of 100 nM SS-14 on Erk1/2 (a) and Akt (b) phosphorylation. (c–d) time-course effect of 100 nM SS-28 on Erk1/2 (c) and Akt (d) phosphorylation. (e–f): dosage-course effect of SS-14 on Erk1/2 (e) and Akt (f) phosphorylation for 10 min treatment. (g–h): dosage-course effect of SS-28 on Erk1/2 (g) and Akt (h) phosphorylation for 10 min treatment. Each value represents mean ± S.E.M, with asterisks indicating significant differences (*p < 0.05. **0.001 < p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 t-test). Original blots are presented in supplementary Fig. S1.

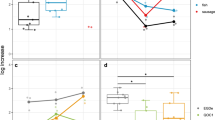

Effect of food intake on the expression of pss2 and sstr3a

To clarify the effect of food intake on PSSs and SSTRs in tilapia, an experiment on feeding and starvation was carried out. As is shown, the tilapia fed for the first time at 9:30 a.m. and the second time at 5:30 p.m. were sampled every two hours post-feeding (Fig. 6a). The gastric appearance and gastric contents were shown: the stomach appearances of the fed group were filled with food from 0 to 4 h post-second feeding and the gastric contents were undigested. The gastric emptying began at 6h post the second feeding. Then, as is shown in the unfed group from 0 to 6 h post the second feeding, which is also the fed group from 8 to 14 h post the first feeding, the gastric appearances continued to empty, and the gastric contents were digested (Fig. 6b).

Effect of food intake on pss and sstrs genes expression of the digestive system of tilapia. (a) experiment design of feeding and starvation experiment. (b) stomach appearance and gastric content in this experiment. (c) effect of feeding on SS and SSTR expression levels in the digestive system. The expression levels were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized against the β-actin gene. Each value represents mean ± S.E.M (n = 8–10). *p < 0.05. **0.001 < p < 0.01.***p < 0.001, t-test.

Further, to clarify the effect of food intake on the expression level of PSSs and SSTRs in the peripheral tissue of tilapia, we detected the PSSs and SSTRs genes expressed in the stomach, Brockmann body, liver, and hindgut by RT-PCR. Referring to the tissue distribution above, the pss2 and sstr3a in the stomach, the pss1 and pss2 in the Brockmann body, the sstr2a and sstr2b in the liver, and sstr5a, sstr2c in the hindgut were selected to test. PSSs were down-regulated and SSTRs were up-regulated by feeding. Especially, the pss2 was down-regulated at 4h and 6h post-feeding and up-regulated at 12h and 14 h, significantly. The pss1 and pss2 were down-regulated at 2h post-feeding significantly and insignificantly, respectively. The sstr3a, sstr5a, and sstr2a were up-regulated from 0 to 4 h post-feeding (Fig. 6c).

The expression level of SSs and SSTRs revealed the effect of food intake on it. Then, we focused on the pss2 and sstr3a which were highly expressed in the stomach. ISH was used to detect the pss2 and sstr3a expression patterns in the stomach. The pss2 was detected in gastric mucosa, which shows the columnar of gastric mucosal epithelial cells (Fig. 7a,b). The sstr3a was detected in gastric submucosa which is full of nerve cells and endocrine cells (Fig. 7c,d).

In situ hybridization of pss2 and sstr3a in the stomach of tilapia. (a, b) antisense and sense probe of pss2. (c, d): antisense and sense probe of sstr3a. The red arrow indicates positive signal, and blue arrows indicate different layers of stomach. Original figures are presented in supplementary Fig. S3.

The expression patterns above reminded us of whether different mechanisms regulate PSSs and SSTRs. To confirm this hypothesis, we gavage food into stomachs ex vivo to simulate the feeding process. In addition, we also gavage PBS into stomachs to simulate the gastric distension caused by feeding. The results showed that food gavage was significantly down-regulated pss2 at 4 h and up-regulated sstr3a at 2 h and 4 h post gavage (Fig. 8a,b).

Effect of food intake and pH on pss2and sstr3a expression level ex vivo. (a–b) effect of food intake on pss2(a) and sstr3a(b) expression level ex vivo, the isolated stomach filling with PBS or food were sampling in 2h and 4h, each value represents mean ± S.E.M (n = 5). (c–d): effect of pH level on pss2 (c) and sstr3a (d) expression level of primary gastric cells, each value represents mean ± S.E.M (n = 3). *p < 0.05. **0.001 < p < 0.01, t-test.

The pH of the stomach is determined by gastric acids secretion, which is regulated by feeding. To clarify the effect of pH on the SS and SSTRs expression level of the feeding, we used DMEM/F-12 medium acidized to pH 5.0 and pH 2.0 to treat primary gastric cells. The pH 2.0 improved the pss2 expression level and sstr3a was unchanged under different pH (Fig. 8c,d).

Discussion

In present study, we identified three PSSs and five SSTRs genes from the telencephalon or pituitary of tilapia. Three PSSs genes and five SSTRs genes were respectively named pss1, pss2, pss3, and sstr2a, sstr2b, sstr2c, sstr3a, sstr3b, sstr5a and sstr5b according to their homology. The pss1 coding prepro-somatostatin has 20 amino acids signal peptide and SS-14 fragment at the C-terminal that is the same as other SS-14 among vertebrates, which presents a conservative in evolution21. Compared with pss1, the SS-14 at C- terminal pss2 produced has a substitution of Tyr7 and Gly10 like other fish species and a substitution of Leu11 tilapia-special4. The pss3 coding SS-14 has a substitution of Pro2 that is considered the most significant character of pss3 in teleost3. Notably, a similar substitution of Pro2 can be found in cortistatin in mammalian and amphibia supporting the homology of pss3 in teleost and Cst in another vertebrate22. All SSTRs are G protein-coupled receptors with seven conservative transmembrane domains and a YANSCANPIL/VLY motif within TMD7 which is considered a signature motif for identification of SSTRs23.

In mammals, pss1-producing SSs exist in pancreas δ-cell and gastrointestinal D-cells, playing important roles in modulating glucose homeostasis, gastric acid secretion, and gastrointestinal motility. However, protein purification from the Brockmann body of tilapia reveals that two distinct SS coded by pss1 and pss2 exist in the Brockmann body4. Our study confirmed that the pss1 and pss2 co-express in the Brockmann body of tilapia indicating that the function of pss2 in teleost shouldn’t be ignored. In stomach, the SS could be identified in many teleost24,25. Further research to distinguish found that SS coding by pss2 seems to be the main type of SS in some teleost26,27,28. In our research, the pss2, instead of pss1, is expressed in the stomach, implying that pss2 replaces pss1 to regulate gastric functions in parts of the teleost. Currently, it’s known that multiple stomach loss and evolutionary events have occurred in fish evolution accompanied by the mutations of the cis-regulatory elements associated with genes29. Considering that both pss1 and pss2 have biological activity, with no deletion or pseudogenization occurring, we believe such substitution might result from analogous changes in chromosomes.

In mammalian intestine, SSs could be detected in endocrine cells and the enteric nervous system involved in the inhibition of intestinal motility, secretory activity, and participating in pathological processes30. Various teleost species exhibit the localization of SS in the intestine24,26,28,31,32,33. However, in another fish, PSSs were not observed in gastroinstestine31,34,35 In this paper, no PSS signal occurs in tilapia from the anterior intestine to the terminal intestine (Fig. 1). Despite the effect of the absence of PSS remains unclear, we speculate that loss of genes might related to adapting to special environments the tilapia lived, in which tilapia could acquire physiological advantages29.

In teleost, sstr3 were first identified in gymnotiform fish with a wide distribution36. Unlike the sstr1 and sstr2 mediating the main gastric function in mammals, sstr3 was found as the highest expressing gastric gene of the SSTRs family in grouper and mandarin fish12,27,37,38. Consistent with other fish, the sstr3a of tilapia is the only highly expressed SSTR in the stomach suggesting that sstr3a might be involved in the regulation of food intake or metabolism in the stomach of teleost, differing from the mammalian. According to the previous study, the sstr5a/b was found an extremely low expression level in all tissue of goldfish and grouper in addition to the pituitary and hind intestine37,39. This pattern was also observed in tilapia, suggesting a special pattern of sstr5a/b. Conclusively, five SSTRs exhibit different expression patterns, suggesting a wide function of the SS family as well as the particularly functional focus of different SSTRs.

Multi SS genes originate from genomic replication events, which is considered the base of multi genes family. In zebrafish, the evolution of SS was firmed that pss1 represents the ancestral gene of the family and pss2 and pss3(cst) arose from random duplication and chromosome duplication, respectively40,41. Radiational phylogenetic tree with uncertain root and genomic synteny analysis are used to reveal the evolution of gene families. In our results, the pss1, pss2, and pss3 of tilapia are clustered within corresponding three clades. The pss1 clade is in the stem of the phylogenetic tree while the pss2 clades and pss3 clades are at the branch of the tree. And pss3 clade is further away from the pss1 clade than the pss2 clade. In addition, pss1 and pss2 of tilapia, zebrafish, and rainbow trout are arranged in tandem on the same chromosomal fragment which is conservative with human chr3.

The pss2 were also identified in some teleosts that undergo a third genome duplication (3R) like stickleback, European eel, and freshwater butterflyfish. In tetrapod, mammalian and some fish didn’t undergo 3R, and pss2 were not been identified42. These evidence indicate a tandem duplication event had happened after 3R in teleost generated the pss2. The pss3(cst) were identified in tetrapod, mammalian, and ray-finned fish43. And several pss3 neighboring genes are orthologous to Chr1 of human that Cst localized, suggesting that a homology between pss3 and cst and pss1 are paralogous to pss3(cst) generated from tetraploidization prior to the fish-tetrapod split44,45. Conclusively, our results support the previous aspect about the evolution of the SS family and add new evidence22,40,41.

The phylogenetic relationships of the SSTRs consist of two major clades, sstr1/4 and sstr2/3/5. The sstr1 clades appear to be a branch of sstr2. The SSTRs genes we identified in this study can be clustered in their corresponding clades indicating their homology. Because of a series of gene duplication events, SSTRs gene family of teleost contains multiple subtypes compared with the mammal increasing complexity of evolution3. The sstr2a/2b and sstr3a/3b localized fragments of fish are partly mapped to chromosomes of human sstr2 and sstr3 localized revealing a homology of sstr2 and sstr3. The sstr2a and sstr3a localized fragments are more conserved in vertebrates than sstr2b and sstr3b suggesting that sstr2a and sstr3a of teleost are orthologous to sstr2 and sstr3 of human37. While the gene copies of some genes neighboring to sstr2a or sstr3a, were found their localization neighboring to sstr2b or sstr3b, such as sox8a/b, sox9a/b, and usp22 of sstr2 or rac2, grab2a/b and cacang2 of sstr3. These observed mapped relationships between sstr2a/3a and sstr2b/3b localized chromosomal fragments reveal that sstr2b and sstr3b are paralogues of sstr2a and sstr3a, respectively. Because the subtypes of sstr2 and sstr3 were not found in tetrapod or mammalian, we speculate duplications of sstr2 and sstr3 generated from duplication events which just happened after fish-tetrapod split44,46. Differ from sstr2/3 and their subtypes, despite sstr5a/b showing a high degree of syntenic relationship among teleost, their fragments of sstr5a/b localized could mapped to two different regions of human chromosome, reminding us of a different evolution history after fish-tetrapod split.

A controversial question of the SS genes family is whether sstr4 exists in teleost3. To date, no sstr4 gene was reported in frog and fish. In our research, sstr4 is also absent in the database. Bioinformatic analysis reveals that sstr1a of zebrafish and rainbow trout could be clustered to sstr4 of chicken37. These results prompt us to compare more genomic data of different species to confirm whether sstr4 exists in bony-fish. Interestingly, the absence of sstr1 was also exhibited in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) and stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) which has a later divergence time compared with zebrafish, rainbow trout, and Ballen wrasse (Larbus bergylta) (These mentioned sequences are referred to the database of ensemble) and we also failed to found sstr1 and its subtypes in tilapia. Redundant gene loss is common in the evolution of multi-gene family47. Thus, we speculate that the sstr1 and its subtypes loss in tilapia and its nearby species due to chromosomal mutants.

The intricate web of intracellular signal transduction mediating functions of the SS family have not been fully clear so far. Erk1/2 is a crucial cellar component for signal transduction that exerts its function by phosphorylation48. The Erk1/2 signal pathway has been proven to mediate the SS function of inhibiting ghr and igf1 expression levels in rainbow trout49. Transient cell line was used routinely to identified the biological functions of receptors, and the transfection have not been found to affect cell activity. In this research, the HEK 293t were transfected with pcDNA3.1(-)/Zeo inserted with five SSTRs separately and treated with synthetic SS-14 and SS-28, whose sequences are consistent with pss1 and pss2 coding mature peptides. The SS-14 or SS-28 treatment stimulates Erk1/2 signal pathway phosphorylation significantly with a dosage-depend increase, suggesting that SSs binding to SSTRs can exhibit their biological functions.

The presence of multi SSTRs genes in many tissues made the diversity of transduction pathways activated by SS treatment. The preference of receptor-effector pathway linkage in different somatostatin receptors is related to particular function50. In rainbow trout primary hepatocytes, SS-14 can mediate Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation through SSTR1a and SSTR2 respectively, and regulate ghr and igf1 gene expression respectively49,51. In grouper primary hepatocytes, SS-14 can also stimulate Erk1/2 and Akt signal pathway and only Akt activation can regulate g6p expression level38. Our experiments implemented in tilapia primary hepatocytes demonstrated that SS-14 can time-related or dosage-depend increase Erk1/2 but not Akt phosphorylation significantly. Interestingly, both Erk1/2 and Akt phosphorylation were activated by SS-28 under 1000 nM. These results remind us of the complexity and divergence of SS function in teleost and provide a new aspect of whether different structures of SSs could have different biological effects.

The amino acid residues Phe7–Trp8–Lys9–Thr10 in SS-14 comprising a β-turn play a necessary role in biological function52. Further study indicates that only the Trp8–Lys9 structure is essential, whereas the amino acids Phe7 and Thr10 could undergo substitution affecting the binding affinity and selectivity7. In tilapia SS-14 coded by pss1 keeping amino acids residues Phe7–Trp8–Lys9–Thr10 remain conservative with other vertebrates and SS-28 coded by pss2 undergo minor substitution e.g. Phe7 → Tyr7 and Thr10 → Gly10, which imply the difference between SS-14 and SS-28 in biological activity and function. Our results showed that SS-14 induced higher activation than SS-28 when binding to four of SSTR in HEK293t cell line and also required a lower concentration for activating phosphorylation in tilapia primary hepatocytes. In rainbow trout liver membrane, SS-25 coded by pss2 has lower binding affinity than SS-14/28 coded by pss17. These results demonstrated that SS-14 having a higher binding affinity and selectivity in the liver might play a more important role in the regulation of liver function. Notably, SSTR5a, the only SSTRs highly expressed in the intestine, exhibit a more significant activation when binding with SS-28 coded by pss2 which is also highly expressed in the gastrointestinal, which implies their interaction regulating gastrointestinal function is possible. In conclusion, diversity of SS-14 and SS-28 in biological function is proposed in this paper and its mechanism is unclear, requesting a pharmacological study in the future.

The study in mammalian showed that SS expressed in mucosal D-cells that terminate close to gastrin-secreting G and pepsinogen-secreting chief cells in the pyloric gland (antrum) and histamine-secreting enterochromaffin-like, acid-secreting parietal, and pepsinogen-secreting chief cells in the oxyntic gland(fundus and corpus), and its function is correlate to restrain on secretion of gastrin, histamine, acid, and pepsinogen12,53. In our research, it was detected that pss2 is expressed in the epithelium of the stomach which positive-cells contain characteristics of neck cells. This property suggests that pss2 of tilapia must be sensitive to intragastric changes.

In vertebrates, it’s reported that somatostatin modulate food intake and digestive activities through the SS signal pathway54,55, meanwhile the presence of food would also regulate the SS and SSTRs expression56,57. The food ingested is temporarily stored in the stomach and intestine resulting in stomach distension and activation of the vagal afferent neurons58. The endocrine factors were significantly up- or down-regulated in response to food intake for digestion and energy balance15. In Coilia nasus, pss2 was significantly decreased in fed versus unfed fish15. In our research, feeding decreased the pss gene expression digestive system in 2–6 h. In addition, we constructed ex vivo model to simulate the food intake process, and the results were consisted with in vivo experiments that the expression of pss2 were down-regulated by food stimulation. Considering that SS is a wide inhibitor for gastrointestinal functions6, we speculated that the down-regulation of pss2 might be benefit to digestion of Gastrointestine when tilapia were feeding.

The absences of food might regulate SS expression with opposite trends. In rat antral and colon, food deprivation was examined to enhance SS and SSTRs expression level16,53. In rainbow trout, long-term starvations increase both pss1,2 and sstr1a, 1b, 2 level59,60. Notably, the increase of gastric pss2 of fed group at 12-14h is consistent with that of unfed group at 4h-6h, suggesting that the expression of gastric pss2 increased at 14-16h after the last feeding. These evidences indicate that pss genes would be up-regulated by starvation in the digestive system. In addition, stomach emptying that requires the inhibition of acid secretion was accompanied by the up-regulation of gastric pss2, and low pH stimulated the pss2 expression ex vivo in our research, which reminds us that the increase of pss2 might be related to inhibiting gastrointestinal activities. The mechanism of regulating the SS signal was complicated. Inconsistency appears in SS expression levels and their protein contents61. It was examined that many factors might modulate sstr gene expression to regulate the SSTRs contents on membrane, which might change the sensitivity of target tissue to the SS ligand, affecting the signal transduction of SS62,63,64. In our research, sstr of tilapia in the stomach, hind intestine, and liver were up-regulated in 2–6 after feeding, which exhibited the opposite trend with PSS genes. It was reported that feeding might stimulate SS-14 and SS-28 secretion in mammals suggesting SS might play an important part in postprandial regulation of vertebrates14,65. The increasing expression of SSTRs family might be satisfactory to the enhancement of SS signaling transduction.

In our research, food gavage simulates the food intake process in vivo contributing to similar changes of pss2 and sstr3a expression levels. Gavaging both PBS and food leads to gastric distension, but only food gavage could increase sstr3a expression level ex vivo, reminding us that the increase of sstr3a is not the result of gastric distension but a complicated mechanism mediated by multi-process. Nutrients were examined as important factors in regulating the somatostatin genes family in peripheral tissues of fish3,66. These evidences remind us that food intake might influent the gastric sstr3a expression level through the nutrient homeostasis mechanism.

In conclusion, this part of the results indicates the dynamic expression of SS family response to food intake. Of these, the pss2 was down-regulated by food stimulation to promote digestion and up-regulated by low pH environment to restrict the secretion of stomach, and the sstr3a was up-regulated by food intake with complicated mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Animals

All tilapia were purchased from the National Tilapia Breeding Farm (Guangzhou, China) and maintained in the tank with 28 °C cycling fresh water under a 12 h:12 h light: dark cycle. Tilapia with body weight of 30 ± 5 g were used for molecular cloning, tissue distribution, and in vivo and ex vivo experiments, while 150 ± 5 g were used for hybridization (ISH).). During the experiment, tilapia were fed twice daily at 9:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. with 2% body weight meal. Tilapia were anesthetized with MS222 and decapitated for sampling. Total RNA samples were stored at − 80 °C for extraction. Samples for ISH were stored in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C.

All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All tilapia were kept experimentally and euthanized strictly followed the ARRIVE guidelines67. During the test, all efforts were made to minimize the suffering of the animals. The Animal Care Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University approved all the experiments (Approval No: SYSU-IACUC-2023-B0453).

Cloning of PSSs and SSTRs cDNAs

Total RNA was extracted from tilapia tissue by TRIZOL(Omega) and dissolved in DEPC-treated water. Then, 1 μg total RNA was used as template to synthesize the first strand cDNA of tilapia using the M-MLV Kit. Oligo dT was used in reverse transcription. Referring to Ensembl and NCBI database, we design the specific 20 bp primers for PSS and SSTR cloning. Using the cDNA as template, we amplify the PSS and SSTRs sequence by Blend Taq Plus PCR system (TOYOBO, Japan). PCR programs are shown as follows: 94 °C 3 min; 94 °C for 30 s, 52–60 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 30–90 s for 35 cycles; 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were purified by E.Z.N.A Gel Extraction Kit and inserted into pUCm-T for sequencing.

RT-PCR

The real-time PCR was used to detect the tissue distribution and gene expression level. Both procedures of them were established in our lab. In brief, total RNA extracted by TRIZOL and digested by DNase I (New England, USA) was applied as template to synthesize cDNAs by M-MLV Kit with random primers. Then, using the products of reverse-transcription as sample, the expression level of genes was detected using SYBR Green PCR mix (DONGSHENG, China). 18s and β-actin, stably expressing housekeeping gene, were selected as internal reference of tissue distribution and gene expression level test, respectively. Amplification reactions were carried out with the Roche LightCycler 480 Real-time PCR Detection System running the thermal cycling program as follows: 95 °C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 56 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. All primers used in this study were shown in Table 1. The Ct values from the instrument were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method compared with internal reference.

Phylogenetic analysis and genomic synteny analysis

PSS and SSTRs protein sequences were aligned and used to construct the Phylogenetic trees with MEGA X using the maximum likelihood method. Data were resampled with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The results of PSSs and SSTRs were shown as radiation tree and rectangle tree respectively. The orthologous PSSs and SSTRs were marked with the same color. The pss2 of zebrafish (Danio rerio) normally known as pss3 and the pss3 of zebrafish normally known as pss2 were uniformed named according to their structure, to avoid confusion.

Genomic synteny analysis of PSSs and SSTRs was performed at Ensembl genome databases based on Ensembl release 109. The Genes around each tilapia SS and SSTRs gene were used to search for orthologs in the genome databases of zebrafish (Danio rerio), rainbow trout, and human (Homo sapience). The identified zebrafish, rainbow trout, and human orthologs retained within a certain syntenic block are shown in the synteny map.

HEK293 cells culture, treatments, and dual-luciferase reporter assay

To determine the biological function of SSTRs, the HEK293T cells dispersed by 0.05% Trypsin were seeded in 24-well plate containing DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and incubated with 5% CO2 under 37 °C for 24h. Then, Medium was aspirated and replaced by Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, USA) and the cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3.1(-)/Zeo-sstr2a/sstr2b/sstr2c/sstr3a/sstr3b/sstr5a/sstr5b, pGL4.33 [luc2P/SRE/Hygro] vector containing a serum response element (SRE) and a pRL-TK for 24 h, which the procedures of cell culture and transfection are like above. To exclude the excluded the effect of endogenous responses, the pcDNA3.1(-)/Zeo-mock vector, pGL4.33 [luc2P/SRE/Hygro] and pRL-TK were co-transfected in same cells culture plate. After 24h of transfection, cells were treated with 0 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, and 1000 nM SS-14 or SS-28 (Synthesized by QIANGYAO) for 4 h. Then, the medium was aspirated and replaced with PBS to wash the cells once. Cells were lysed by 100 μL RIPA buffer containing a final concentration of 1 × protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail per well. The lysate was centrifuged by 10,000g to remove cell debris.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay System (Promega, USA) was used to determine the biological function of SSTRs. 20 μL lysate harvested by the above procedures was added to 20 μL LAR II and mixed for the first measurement. After the first measurement, 20 µl Stop & Glo Reagent was added into the system for the second measurement. The fluorescence values of SSTRs need to be subtracted the fluorescence values of mock in same dosages before significant analysis.

Hepatocyte isolation, culture, treatments, and western blot

The method of tilapia primary hepatocytes isolation was described previously38. In brief, the liver separated and placed in HBSS was fragmented and digestive by Collagenase IV and DNase II at 28 °C for 20 min. Then, the fragments were mechanically dispersed and filtered through sterile nylon gauze (250 μm, 150 μm, 75 μm-mesh). Following that, the dispersed cells were centrifuged by 70g 5 min, 50g 5 min, and 30g 5 min to collect the cells and remove cell debris. The collected cells were resuspended by L-15 containing 10% FBS and counted by blood counting chamber with Trypan blue exclusion method. The dispersed primary hepatocytes were seeded in 24-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well and incubated at 28 °C overnight.

After overnight culture, the medium was aspirated and replaced by FBS-free L-15. The tilapia primary hepatocytes were treated for 1h before SS treatment. In the time-course experiments, hepatocytes were treated by 100 nM SS-14 or SS-28 for 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 30 min and 60 min. In the dosage-course experiments, hepatocytes were treated by 0 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, and 1000 nM for 10 min. At the end of treatment, mediums were removed and hepatocytes were lysed by RIPA buffer containing a final concentration of 1 × protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged by 13000 g for 15 min.

To examine the effect of SS on hepatocytes, western blot was used to detect phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and Akt. The procedure of western blot was described previously. In brief, 10 μg of total protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and transmembrane to 0.45 μm PVDF membrane. The membranes were blocked by 5%(w/v) skimmed milk powder and incubated with antibodies (CST, USA) dissolved in TBST buffer containing 5% (w/v) BSA and 0.02% NaN3 overnight in 4 °C. The membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with HRP for 1 h under room temperature. Finally, the ECL Kit was used to detect the membrane visually.

Feeding and starvation experiments of tilapia

Tilapia with body weight of 30 ± 5 g were used for feeding experiment. Before the experiment, tilapia were fed twice daily at 9:30 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. with 2% body weight meal. In the experiment, both groups of tilapia were fed at 9:30 a.m., then the feeding group of tilapia remained fed at 5:30 p.m. while the unfed group stopped feeding. Samplings were taken every 2 h from the time of feeding at 5 p.m. Tilapia were anesthetized with MS222 and decapitated for sampling. Total RNA samples were stored at − 80 °C for extraction.

In-situ hybridization

The method of bleach section was used for in situ hybridization. To synthesize the probe, the linearized pGEM-T easy inserted the fragment of pss2 and sstr3a were used as template to transcript the probe by the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (Roche, USA).

The stomach of tilapia was separated and placed in 4% PFA for 24h under 4 °C. We transfer the stomach into 30% sucrose solution for 36 h till the stomach already sinking to the bottom. The dehydrated stomach was cut 50 μm sections by using vibratome. Then, we collect the section on ice PBS and fix it by 4% PFA overnight. To pre-treat the section before hybridization, the section was washed with PBS for 10 min trices and 0.75% Glycin/PBS for 15 min twice. Then, we permeabilize the section with 0.3% tritonX100 for 20 min and equilibrate the section with acetylation buffer containing Triethanolamine, adding acetic anhydride for 10 min incubation. Following the pretreatment, we pre-hybrid section with hybridization buffer for 1h under 55 °C and added the preheated probes for a 1:100 dilution ratio to hybrid at 55 °C for 16–20 h.

After hybridization, the section was washed by 2 × SSC/50%Formamide/0.1%N-Lauroylsarcosine for 20 min twice, 2 × SSC/0.1%N-Lauroylsarcosine for 20 min twice and 0.2 × SSC/0.1% N-Lauroylsarcosine 20 min twice. The section was transferred to MABT (maleic acid buffer adding 1% Tween20) for washing and blocked by blocking buffer (MABT containing 1% blocking reagent (Roche, USA) and 10% FBS) for 1h at room temperature. Dilute anti-DIG-AP (Roche, USA) 1:1000 in blocking buffer and incubate the section at 4 °C overnight.

After the overnight incubation, the section was washed by MABT for 30 min six times at room temperature and equilibrated for 10 min in NTMT buffer (1M Tris–HCl, 5M NaCl, 1M MgCl2, and pH 9.5). Dilute NBT/BCIP (Roche, USA) in a 1:500 ratio into NTMT buffer and incubate the section under the dark for colorimetric reaction. After a 4-5h incubation at room temperature, the PBS was used to stop the reaction, and the section was transferred to slides for observation under microscopy. The pictures of slides were captured by Nikon Eclipse Ni-E.

Ex vivo model

Referring to the protocol described before68, we construct an ex vivo model of tilapia stomach. In short, the tilapia was decapitated as above, stomachs were collected and we removed the gastric contents by PBS. The pylorus end of stomach was ligated by hemostatic clamp, and the stomachs were gavaged via esophagus with feed mixture or PBS until fully distended, following the esophagus was also ligated by hemostatic clamp. The feed mixture was made of feed pellets homogenized with water until the mixture could be squeezed out from the injector. Full and empty stomachs were then immersed in Kreb’s solution (118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 11.0 mM glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2 at pH7.4) at 28 °C for incubation. In another experiment, PBS was replaced by Kreb’s solution acidified to pH5.0 and pH2.0 with acetic acid to gavage stomachs, the stomachs were then immersed in Kreb’s solution at 28 °C for incubation. After incubation, the stomachs were opened and sampled as described above.

Primary gastric cells isolation and treatment

The method of primary gastric cells isolation was mentioned as follows. In brief, the intact stomach was separated and placed in D′-Hanks solution. The gastric contents should be removed. We used slide to scrape off the inner tissue of gastric and collected them. Collagen I and Collagen IV were used to digest the tissue under 28 °C water baths. The tissues were mechanically dispersed and filtered through sterile nylon gauze (150 μm-mesh). The cells were centrifuged under 800 rpm for 5 min for harvest. The harvested cells were resuspended and counted. 1 × 105 cells were seeded in 24-well plate per well and cultured with DMEM/F-12 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% insulin transferrin selenium (ITS) and incubated with 5% CO2 under 28 °C. After 48h culture, the mediums were removed and the new DMEM/F-12 mediums acidified to pH5.0 and pH2.0 were added. After 1–2 h treatments, cells were collected, and detected the expression level.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by t-test or one-way ANOVA by SPSS25. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Data availability

The DNA sequences data generated during the current study are available in the Genebank. Accession number are as follow: pss1 (MW848783.1), pss2 (MW848784.1), pss3 (MW848785.1), sstr2a (MW848786.1), sstr2b (MW848787.1), sstr3a (MW848788.1), sstr3b (MW848789.1), sstr5a (MW848790.1). The other raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author (Prof. Wensheng Li, lsslws@mail.sysu.edu.cn), without undue reservation.

References

Brazeau, P. et al. Hypothalamic polypeptide that inhibits the secretion of immunoreactive pituitary growth hormone. Science 179, 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.179.4068.77 (1973).

Nelson, L. E. & Sheridan, M. A. Regulation of somatostatins and their receptors in fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 142, 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.12.002 (2005).

Lin, X. W. & Peter, R. E. Somatostatins and their receptors in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B-Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 543–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00362-1 (2001).

Nguyen, T. M., Wright, J. R. Jr., Nielsen, P. F. & Conlon, J. M. Characterization of the pancreatic hormones from the Brockmann body of the tilapia: Implications for islet xenograft studies. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 111, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-8413(95)00023-z (1995).

Rorsman, P. & Huising, M. O. The somatostatin-secreting pancreatic delta-cell in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-018-0020-6 (2018).

Moller, L. N., Stidsen, C. E., Hartmann, B. & Holst, J. J. Somatostatin receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1616, 1–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00235-9 (2003).

Sheridan, M. A., Kittilson, J. D. & Slagter, B. J. Structure-function relationships of the signaling system for the somatostatin peptide hormone family. Am. Zool. 40, 269–286 (2000).

Tostivint, H. et al. Molecular evolution of GPCRS somatostatin/urotensin II receptors. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 52, T61–T86. https://doi.org/10.1530/Jme-13-0274 (2014).

Patel, Y. C. Somatostatin and its receptor family. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 157–198. https://doi.org/10.1006/frne.1999.0183 (1999).

Stengel, A., Karasawa, H. & Taché, Y. The role of brain somatostatin receptor 2 in the regulation of feeding and drinking behavior. Horm. Behav. 73, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.009 (2015).

Tachibana, T., Cline, M. A., Sugahara, K., Ueda, H. & Hiramatsu, K. Central administration of somatostatin stimulates feeding behavior in chicks. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 161, 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.01.022 (2009).

Schubert, M. L. & Rehfeld, J. F. Gastric peptides-gastrin and somatostatin. Compr. Physiol. 10, 197–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c180035 (2020).

Penman, E. et al. Response of circulating immunoreactive somatostatin to nutritional stimuli in normal subjects. Gastroenterology 81, 692–699 (1981).

Ensinck, J. W., Vogel, R. E., Laschansky, E. C. & Francis, B. H. Effect of ingested carbohydrate, fat, and protein on the release of somatostatin-28 in humans. Gastroenterology 98, 633–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(90)90282-6 (1990).

Ma, F. J. et al. Insights into response to food intake in anadromous Coilia nasus through stomach transcriptome analysis. Aquac. Res. 51, 2799–2812. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.14619 (2020).

Kido, T. et al. Food deprivation enhances somatostatin and somatostatin receptor subtype expression in rat colon. Regul. Pept. 114, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-0115(03)00122-8 (2003).

Peterson, B. C., Bilodeau-Bourgeois, A. L. & Small, B. C. Response of the somatotropic axis to alterations in feed intake of channel catfish (). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 153, 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.04.614 (2009).

Weng, Y. & Fang, Y. Effects of starvation on the morphology, localization and distributional density of endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract of juvenile Epinephelus coioides. J. Oceanogr. Taiwan Strait 30, 10–16 (2011).

Uvnas-Wallensten, K., Efendic, S., Johansson, C., Sjodin, L. & Cranwell, P. D. Effect of intraluminal pH on the release of somatostatin and gastrin into antral, bulbar and ileal pouches of conscious dogs. Acta Physiol. Scand. 110, 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1980.tb06686.x (1980).

Kuniyoshi, N. Relation of intragastric pH with the response of gastrin and somatostatin secretion to electrical vagal stimulation. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi Jpn. J. Gastro-enterol. 88, 2085–2093 (1991).

Lin, X.-W., Otto, C. J. & Peter, R. E. Evolution of neuroendocrine peptide systems: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and somatostatin. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 119, 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0742-8413(98)00025-5 (1998).

Tostivint, H. et al. Linkage mapping of the [Pro2]somatostatin-14 gene in zebrafish: Evolutionary perspectives. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1040, 486–489. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1327.098 (2005).

Bell, G. I. & Reisine, T. Molecular biology of somatostatin receptors. Trends Neurosci. 16, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(93)90050-v (1993).

Ozen, M. R., Cinar, K. & Senol, N. Endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract mucosa of zander (Stizostedion lucioperca). Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 16, S339–S345 (2010).

Jingfeng, W., Yang, L. I. U., Qin, Z., Long, P. & Changhu, X. U. E. Immunocytochemistry study on somatostatin secreting cells in Paralichtys olivaceus. J. Fish. Sci. China 14, 397–402 (2007).

Youson, J. H., Al-Mahrouki, A. A., Naumovski, D. & Conlon, J. M. The endocrine cells in the gastroenteropancreatic system of the bowfin, Amia calva L.: An immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and immunocytochemical analysis. J. Morphol. 250, 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.1066 (2001).

Dai, W., Zhao, J.-L., Mia, T.-T. & Guo, J.-T. Cloning and expression of two somatostatin receptor genes in Siniperca chuatsi. Chin. J. Zool. 47, 93–100 (2012).

Ying, Y., Li, W. S. & Lin, H. R. Polygenic expression of somatostatin in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides): Molecular cloning and distribution of the mRNAs encoding three somatostatin precursors. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 241, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2005.05.008 (2005).

Kato, A. et al. Convergent gene losses and pseudogenizations in multiple lineages of stomachless fishes. Commun. Biol. 7, 408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06103-x (2024).

Gonkowski, S. & Rytel, L. Somatostatin as an active substance in the mammalian enteric nervous system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20184461 (2019).

Lee, J. H., Ku, S. K., Park, K. D. & Lee, H. S. Immunohistochemical study of the gastrointestinal endocrine cells in the Korean aucha perch. J. Fish Biol. 65, 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-1112.2004.00442.x (2004).

Cinar, K., Senol, N. & Ozen, M. R. Immunohistochemical study on distribution of endocrine cells in gastrointestinal tract of flower fish (Pseudophoxinus antalyae). World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 6874–6878 (2006).

Lin, X. Z., Wang, P. F., Ou, Y. J., Li, J. E. & Wen, J. F. An immunohistochemical study on endocrine cells in the neuroendocrine system of the digestive tract of milkfish Chanos chanos (Forsskal, 1775). Aquac. Res. 48, 1439–1449. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.12979 (2017).

Vieira-Lopes, D. A. et al. Immunohistochemical study of the digestive tract of Oligosarcus hepsetus. World J. Gastroenterol. 19, 1919–1929. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1919 (2013).

Cardoso, N. D. et al. Histochemical and immunohistochemical study on endocrine cells (5HT, GAS, and SST) of the gastrointestinal tract of a teleost, the characin Astyanax bimaculatus. Acta Histochem. 117, 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2015.05.007 (2015).

Zupanc, G. K. H. et al. Molecular cloning and pharmacological characterization of a somatostatin receptor subtype in the gymnotiform fish Apteronotus albifrons. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 115, 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1006/gcen.1999.7316 (1999).

Dong, H. Y., Li, W. S. & Lin, H. R. Comparative analyses of sequence structure, evolution, and expression of four somatostatin receptors in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides). Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 323, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2010.03.016 (2010).

Zhang, Y. Z. et al. Molecular identification, tissue distribution and functional analysis of somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) in red-spotted grouper (Epinephelus akaara). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 274, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.01.007 (2019).

Lin, X. W., Nunn, C., Hoyer, D., Rivier, J. & Peter, R. E. Identification and characterization of a type five-like somatostatin receptor in goldfish pituitary. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 189, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00745-6 (2002).

Tostivint, H., Lihrmann, I. & Vaudry, H. New insight into the molecular evolution of the somatostatin family. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 286, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.029 (2008).

Liu, Y. et al. The evolution of somatostatin in vertebrates. Gene 463, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2010.04.016 (2010).

Meyer, A. & Van de Peer, Y. From 2R to 3R: Evidence for a fish-specific genome duplication (FSGD). BioEssays 27, 937–945. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20293 (2005).

Tostivint, H., Joly, L., Lihrmann, I., Ekker, M. & Vaudry, H. Chromosomal localization of three somatostatin genes in zebrafish. Evidence that the [Pro2]-somatostatin-14 isoform and cortistatin are encoded by orthologous genes. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 33, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1677/jme.1.01602 (2004).

Dehal, P. & Boore, J. L. Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol. 3, 1700–1708. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030314 (2005).

Van de Peer, Y., Maere, S. & Meyer, A. OPINION the evolutionary significance of ancient genome duplications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2600 (2009).

Hoegg, S., Brinkmann, H., Taylor, J. S. & Meyer, A. Phylogenetic timing of the fish-specific genome duplication correlates with the diversification of teleost fish. J. Mol. Evol. 59, 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-004-2613-z (2004).

Gout, J. F. & Lynch, M. Maintenance and Loss of Duplicated Genes by Dosage Subfunctionalization. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32(8), 2141–2148 (2015).

Amin, M. A. et al. Migration inhibitory factor mediates angiogenesis via mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol kinase. Circ. Res. 93, 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.Res.0000087641.56024.Da (2003).

Hagemeister, A. L. & Sheridan, M. A. Somatostatin inhibits hepatic growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor I mRNA expression by activating the ERK and PI3K signaling pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295, R490–R497. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00099.2008 (2008).

Olias, G., Viollet, C., Kusserow, H., Epelbaum, J. & Meyerhof, W. Regulation and function of somatostatin receptors. J. Neurochem. 89, 1057–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02402.x (2004).

Hagemeister, A. L., Kittilson, J. D., Bergan, H. E. & Sheridan, M. A. Rainbow trout somatostatin receptor subtypes SSTR1A, SSTR1B, and SSTR2 differentially activate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathways in transfected cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 45, 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1677/jme-10-0046 (2010).

Veber, D. F. et al. Highly active cyclic and bicyclic somatostatin analogues of reduced ring size. Nature 280, 512–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/280512a0 (1979).

Wu, V., Sumii, K., Tari, A., Sumii, M. & Walsh, J. H. Regulation of rat antral gastrin and somatostatin gene expression during starvation and after refeeding. Gastroenterology 101, 1552–1558. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(91)90391-w (1991).

Chaudhri, O., Small, C. & Bloom, S. Gastrointestinal hormones regulating appetite. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 361, 1187–1209. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2006.1856 (2006).

Shamsi, B. H., Chatoo, M., Xu, X. K., Xu, X. & Chen, X. Q. Versatile functions of somatostatin and somatostatin receptors in the gastrointestinal system. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.652363 (2021).

Schwarting, H., Koop, H., Gellert, G. & Arnold, R. Effect of starvation on endocrine cells in the rat stomach. Regul. Pept. 14, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-0115(86)90203-x (1986).

Wu, S. V., Sumii, K., Tari, A., Mogard, M. & Walsh, J. H. Regulation of gastric somatostatin gene expression. Metab. Clin. Exp. 39, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(90)90229-6 (1990).

Le Bail, P.-Y. & Boeuf, G. What hormones may regulate food intake in fish?. Aquat. Living Resour. 10, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1051/alr:1997041 (1997).

Ehrman, M. M., Melroe, G. T., Moore, C. A., Kittilson, J. D. & Sheridan, M. A. Nutritional regulation of somatostatin expression in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 26, 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:FISH.0000009261.30672.3a (2002).

Slagter, B. J., Kittilson, J. D. & Sheridan, M. A. Somatostatin receptor subtype 1 and subtype 2 mRNA expression is regulated by nutritional state in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 139, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.09.008 (2004).

Holloway, A. C., Reddy, P. K., Sheridan, M. A. & Leatherland, J. F. Diurnal rhythms of plasma growth hormone, somatostatin, thyroid hormones, cortisol and glucose concentrations in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, during progressive food deprivation. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 25, 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09291019409360312 (1994).

Nelson, L. E. & Sheridan, M. A. Insulin and growth hormone stimulate somatostatin receptor (SSTR) expression by inducing transcription of SSTR mRNAs and by upregulating cell surface SSTRs. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 291, R163–R169. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00754.2005 (2006).

Very, N. M. & Sheridan, M. A. Somatostatin regulates hepatic growth hormone sensitivity by internalizing growth hormone receptors and by decreasing transcription of growth hormone receptor mRNAs. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 292, R1956–R1962. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00689.2006 (2007).

Pesek, M. J. & Sheridan, M. A. Fasting alters somatostatin binding to liver membranes of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Endocrinol. 150, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.1500179 (1996).

Schusdziarra, V. et al. Pancreatic and gastric release of somatostatinlike immunoreactivity during intestinal phase of a meal. Am. J. Physiol. 237, E555-560. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.6.E555 (1979).

Kittilson, J. D., Slagter, B. J., Martin, L. E. & Sheridan, M. A. Isolation, characterization, and distribution of somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (SSTR 2) mRNA in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and regulation of its expression by glucose. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A-Mol. Integr. Physiol. 160, 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.06.009 (2011).

du Sert, N. P. et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 20. PLoS. Biol. 18, e3000411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411 (2020).

Saqui-Salces, M., Dowdle, W. E., Reiter, J. F. & Merchant, J. L. A high-fat diet regulates gastrin and acid secretion through primary cilia. Faseb J. 26, 3127–3139. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.11-197426 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFF1000301), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-46) to Dr Wensheng Li. National Science Foundation of China (32373102, 32072968, 32102761) also provided important assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ran Cai designed the major study and finished formal analysis, is the first author, wrote this article and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Jiahui Zhang finished molecular cloning and partial cell experiments. Xiaozheng Yu, Yang Yu, and Zongzhen Liao collected the samples and assisted in all the experiments. Wensheng Li designed this research and finished formal analysis, is the corresponding author, reviewed and revised the article, and acquired, funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, R., Zhang, J., Yu, X. et al. Molecular identification of somatostatin family in tilapia and the effect of food intake on pss2 and sstr3a. Sci Rep 15, 12695 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97228-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97228-4