Abstract

This retrospective study analyzed 306 pregnant women, with 182 undergoing genetic testing using NIPT plus and CMA, and 124 undergoing standard NIPT and CMA. The study aimed to compare the clinical performance of NIPT and NIPT plus in prenatal evaluation by using CMA as the gold standard to assess the diagnostic efficiency of the two screening methods. NIPT plus and NIPT results were correlated with ultrasound findings to evaluate their accuracy and clinical utility. The diagnostic performance of each method was compared against CMA to assess sensitivity, specificity, false positive and false negative rates, as well as positive predictive value and negative predictive value. The combined use of NIPT plus and ultrasound significantly improved the detection rate of sex chromosome aneuploidy (SCA), microdeletion/microduplication syndromes (MMS), and rare autosomal trisomies (RAT) compared to NIPT plus alone. Ultrasound combined with NIPT plus achieved the highest sensitivity (88.24%) for SCA/RAT/ MMS. However, NIPT plus exhibited a higher false positive rate compared to standard NIPT. In contrast, NIPT combined with ultrasound demonstrated the highest PPV (88.89%) for common trisomies (T13, T18, T21). False negatives were more prevalent in standard NIPT, particularly for SCA, MMS, and RAT, emphasizing its limitations for detecting complex chromosomal abnormalities. NIPT plus, when combined with ultrasound, offers significant improvements in the detection of rare chromosomal abnormalities like SCA, MMS, and RAT, while maintaining high detection rates for common trisomies. Although NIPT plus has a higher false positive rate, the inclusion of ultrasound enhances screening accuracy and clinical decision-making. This study supports the use of NIPT plus combined with ultrasound as the optimal screening strategy, particularly for rare and complex chromosomal abnormalities, while standard NIPT remains highly effective for screening common trisomies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trisomy 21 (T21), Trisomy 18 (T18), and Trisomy 13 (T13), along with sex chromosome aneuploidies (SCA), constitute a significant portion of the chromosomal abnormalities encountered in fetal development1. In recent years, noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) has revolutionized prenatal care, offering an effective screening tool for detecting common fetal trisomies. Since 2011, China has adopted NIPT as a screening tool for detecting common fetal trisomies, marking a transformative step in prenatal genetic assessment. Supported by the China Food and Drug Administration, NIPT is becoming a standard practice in prenatal care, utilizing cell-free DNA (cfDNA) sequencing from maternal plasma to screen for chromosomal abnormalities2. This approach has improved the speed and accuracy of early fetal screening, allowing for timely information that can inform clinical decision-making for expecting parents3.

However, despite NIPT’s widespread adoption, certain limitations remain3,4,5,6,7,8. While NIPT has demonstrated high accuracy for detecting common trisomies, it has a reduced ability to identify other genetic conditions, such as rare autosomal trisomies (RAT) and structural chromosomal abnormalities9,10. This limitation is particularly concerning as these conditions, though less frequent, can have significant clinical consequences. This limitation is particularly concerning as these conditions, though less frequent, can have significant clinical consequences. To address these limitations, advanced versions of NIPT, such as NIPT plus, have been developed. NIPT plus expands the scope of prenatal screening, including a broader range of genetic abnormalities such as RAT, microdeletions/microduplications (MMS), and sex chromosome aneuploidies (SCA)11. While other advanced methods, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS) or chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), offer high accuracy for detecting a wider array of genetic abnormalities, they are typically more invasive, costly, and less feasible for routine clinical use compared to NIPT plus12. NIPT plus retains the noninvasive nature of traditional NIPT, making it more suitable for widespread use in clinical practice.

NIPT plus employs a higher sequencing depth and provides more comprehensive information, offering improved detection rates for conditions that are missed by standard NIPT. However, the introduction of NIPT plus brings new challenges, particularly regarding its higher cost, ethical considerations, and the potential for false positives due to its broader testing scope11,13. SCA involve numerical abnormalities in the sex chromosomes, such as monosomy X (45, X), trisomies (47, XXX; 47, XXY; 47, XYY), and mosaic forms (e.g., 45, X/46, XY). Monosomy X often shows ultrasound abnormalities like cystic hygroma, while other types typically have milder clinical features and fewer ultrasound findings. Detection rates and ultrasound indicators vary by SCA type14.

NIPT plus employs a higher sequencing depth than standard NIPT15, allowing for improved detection of copy number variations (CNV) related to MMS, with a higher positive predictive value for variants over 10 Mb15. Although NIPT plus extends the scope of prenatal screening, its application remains limited due to factors such as high costs, insufficient clinical utilization data, and the need for extensive follow-up16,17,18, which currently restricts its benefits to a smaller subset of pregnant women11.

The clinical relevance of comparing NIPT and NIPT plus is substantial. While both methods offer significant advantages in prenatal screening, their differing capabilities in detecting chromosomal abnormalities could have substantial implications for clinical recommendations. In practice, determining when and how to incorporate NIPT plus into prenatal screening is a critical decision for healthcare providers, especially as the combination of NIPT plus with ultrasound may improve detection accuracy for rare and complex genetic conditions. However, the lack of sufficient data comparing the two methods in combination with ultrasound limits the ability to make fully informed decisions.

This study aims to evaluate the screening performance of both NIPT and NIPT plus, with a particular focus on assessing their effectiveness in combination with ultrasound for comprehensive prenatal screening. By directly comparing these screening strategies, we seek to provide practical insights into which method offers the best diagnostic efficacy for detecting a broad range of chromosomal abnormalities. The findings of this study will inform clinical recommendations and help optimize prenatal care practices, particularly for pregnant women at risk of genetic conditions beyond the common trisomies.

Materials and methods

Subjects

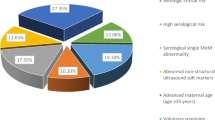

The retrospective analysis included a total of 306 pregnant women aged 21 to 46 years. We enrolled a total of 182 pregnant women, including 11 pregnant women with monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA) pregnancies and 171 pregnant women with singleton, who underwent both NIPT plus and chromosome microarray analysis (CMA). The age range of the pregnant women was from 21 to 44 years old. Additionally, 124 pregnant women, including 2 with MCDA pregnancies, underwent both NIPT and CMA at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University from January 2021 to December 2022. The age range of these pregnant women was from 21 to 46 years old. As all the pregnant women included in the analysis underwent both NIPT plus/NIPT and CMA, and are clinically considered to be at risk for chromosomal abnormalities, we classified them as high-risk pregnancies (Fig. 1).

Note on Selection Bias: As this study is retrospective, potential selection bias may exist. The pregnant women enrolled in the study were not randomly selected, and their inclusion was based on pre-existing medical records from our hospital.

Ultrasound screening

Ultrasound screening is performed by specialist obstetric sonographers, following appropriate practices for screening for fetal abnormalities19. The sonographers conducting the ultrasound were blinded to the genetic screening results to prevent bias in the detection of abnormalities. Ultrasound follow-up is performed throughout pregnancy or until pregnancy termination, including screening at 6–8 weeks of early pregnancy, posterior nuchal translucency scan (NT screening) at 11–13 weeks, exclusion of major fetal anomalies at 20–24 weeks, exclusion of minor fetal anomalies at 28–32 weeks, and a final prenatal check-up. Fetal macro-anomaly screening is mainly for developmental anomalies such as anencephaly, severe brain enlargement, severe open spina bifida, severe abdominal wall defects and visceral ectopia, single-chambered heart, lethal chondrodysplasia, and limb deformities. Fetal micro anomaly screening screens fetuses for abnormalities such as hydrocephalus, hydronephrosis, polycystic kidneys, duodenal atresia, and cystic adenomas of the lungs. Checks for major mid-pregnancy screening, as well as detecting late-onset malformations. Fetal ultrasound findings include soft markers, structural abnormalities, fetal growth restriction (FGR), and polyhydramnios. FGR is defined as estimated fetal weight below the 10th percentile for gestational age20. As long as one abnormality is present throughout the follow-up period, we defined it as a positive ultrasound screen. Ultrasonographic abnormal findings were divided into 9 groups: G1: soft markers; G2: structural abnormalities; G3: soft markers and structural abnormalities; G4: soft markers and FGR; G5: abnormal amniotic fluid volume, structural abnormalities, and FGR; G6: FGR; G7: structural abnormalities and FGR; G8: stillbirth; G9: Abnormal amniotic fluid volume. The rationale for combining ultrasound with NIPT/NIPT plus is based on the complementary nature of these screening methods. Ultrasound provides anatomical and developmental insights, identifying structural abnormalities, soft markers, and conditions like FGR that are not detectable through genetic screening. In contrast, NIPT and NIPT plus primarily screen for chromosomal abnormalities, including trisomies and other large-scale genomic imbalances. By integrating ultrasound with NIPT/NIPT plus, the strengths of both methodologies are leveraged, optimizing prenatal screening effectiveness and enabling more informed clinical decision-making.

Sample preparation and sequencing

For the analysis, 8–10 mL of maternal peripheral blood was collected in an EDTA anticoagulant tube, with plasma separation completed within 8 h of collection. cfDNA was extracted from the plasma using the Darui Fetal Chromosome Aneuploidy Testing Kits (Darui Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), which are designed for the detection of chromosomal aneuploidies, including trisomies 21, 18, and 13. The same kit was used for both NIPT and NIPT plus, ensuring consistency in cfDNA extraction.

Quantification of the extracted DNA was performed using a Qubit fluorometer, with a minimum of three samples per batch. Only samples with a cfDNA concentration greater than 0.05 ng/μL proceeded to library construction; if repeated extractions yielded insufficient cfDNA levels, additional blood was drawn. For library construction, the cfDNA was processed following the manufacturer’s protocol to ensure optimal sequencing results.

The DNA fragment size for standard NIPT is approximately 150 bp, while for NIPT plus it is reduced to around 120 bp. This shorter fragment size in NIPT plus improves sensitivity, particularly for detecting microdeletions and microduplications. Additionally, after enrichment, the fetal fraction in NIPT plus samples is generally more than twice that of standard NIPT, enhancing the detection capability for chromosomal abnormalities.

After library preparation and quantification, libraries with a concentration above 0.2 ng/μL were considered qualified for sequencing; otherwise, DNA re-extraction and library reconstruction were required.

Sequencing was performed using the Daan da8600 Proton Platform (Daan Gene Sequencer, Guangzhou, China), which employs semiconductor sequencing technology. Sequencing results underwent bioinformatics processing, including the Z-score method, to detect fetal chromosomal aneuploidies. NIPT plus also included additional algorithms to enhance the detection of smaller CNV, leveraging its higher sensitivity and improved analysis capabilities. The analysis plugins used for NIPT and NIPT plus was “DaRuiCNV_ALPHA”.

For standard NIPT, a high-risk result is reported for trisomies 13, 18, and 21 when the Z-score exceeds 3. In cases where cfDNA concentration is above 10%, fragment size is over 10 Mb, and Z-score is greater than 5, supplementary reports onSCA, MMS, and RAT are provided.

Our hospital offers two NIPT testing options: the Basic Version (NIPT) and the Upgraded Version (NIPT plus), with differences in detection coverage and thresholds as Table 1. A Z-score > 3 for NIPT is considered a high-risk result. This threshold was chosen based on references in prenatal screening6,21,22. A Z-score > 5 is required for NIPT plus, because NIPT plus has higher sequencing depth (~ 120 bp) This threshold was selected to increase the specificity of the assay, reducing the likelihood of false positives while maintaining sensitivity for detecting true abnormalities21.

Note on Bias Control in Analysis: The genetic analysts conducting the sequencing and analysis were not blinded to the clinical history or ultrasound results, which could potentially introduce bias in interpreting the results.

Prenatal diagnosis

CMA was performed on the single-nucleotide polymorphism array platform using CytoScan HD arrays according to the manufacturer’s standard operating procedures (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The raw data were analyzed using Chromosome Analysis Suite software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the CNV were called using a minimum size of 100 kb as indicated by at least 50 probes. The main reason we chose CMA as a diagnostic criterion is that without prenatal diagnosis, the accuracy of screening results can only be determined by follow-up, but not all CNV will present at follow-up, which may lead to an incorrect diagnosis. The reason why we chose CMA as the standard rather than karyotype is that the target abnormalities for NIPT screening are chromosomal aneuploidy and CNV, which can be detected by CMA without the need for karyotype.

Note on Bias Control: Genetic analysts interpreting the CMA results were not blinded to the initial screening outcomes.

Definitions of ultrasound, NIPT, NIPT plus true positive, false positive, false negative and detection rates

In this study, we used CMA as the gold standard for prenatal diagnosis, while NIPT and NIPT plus were used as screening methods. Definitions of ultrasound, NIPT, NIPT plus true positive (TP), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) are shown in Table 2. detection rates = (TP + FP)/ (TP + FP + FN).

Follow-up of pregnancy outcomes

We followed up on the pregnancy outcomes of all pregnant women included in the study. All newborns are examined by a pediatrician, and those with suspected chromosomal abnormalities receive further examination and diagnosis. Telephone follow-up of parents at prenatal diagnostic centers and home visits in the community to assess the growth and development of the fetus. NIPT/ NIPT plus positive and FN results are covered by insurance. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki (as amended in 2013). As this study is retrospective, informed consent was not required, and an exemption was granted.

Note on Recall Bias: Given the retrospective nature of this study, recall bias may be a concern, as follow-up data depend on the accuracy of information provided by parents. This limitation should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by SPSS. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predict value (PPV), and negative predict value (NPV) were calculated using the results of CMA as the reference standard. Significance was fixed at P < 0.05. All figures are finished by Keynote.

Result

The screening sensitivity of NIPT and NIPT plus

In this study, we analyzed the results of a total of 306 pregnant women aged 21–46 years. Of these, 124 participated in the NIPT analysis and 182 participated in the NIPT plus analysis (Fig. 1). All of the pregnant women were within 12–22 weeks of gestation. Additionally, all fetal DNA concentrations were above 5%, meeting the analysis criteria.

Comparison of NIPT plus/NIPT combined with ultrasound (or not) and CMA results

Figure 2 illustrates that NIPT plus can detect SCA, MMS, and RAT, which are beyond the detection scope of standard NIPT. Therefore, direct comparison between NIPT plus and standard NIPT for RAT and MMS is somewhat limited, as these abnormalities fall outside standard NIPT screening parameters. Nevertheless, supplementary reports are provided under specific conditions, and thus, NIPT results for these cases are included in Supplementary Table 3 and Table 4. However, detection rates for MMS and RAT in NIPT plus are relatively lower compared to other conditions.

Combining ultrasound with NIPT plus significantly improves detection accuracy, achieving 81.82% for MMS, 100% detection for SCA and RAT. For SCA, ultrasound + NIPT improves detection from 83.3% (NIPT alone) to 100%.

T13 was not detected by standard NIPT during the study period (2021–2022), while NIPT plus reported one false positive case. NIPT plus and ultrasound + NIPT plus maintain 100% detection for common trisomies (T13, T18, T21).

Overall, the combination of NIPT plus and ultrasound emerges as the most effective strategy, improving detection rates across multiple conditions.

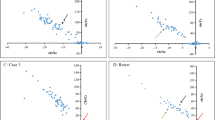

Performance of screening strategies

We evaluated four screening strategies: NIPT, NIPT plus, NIPT combined with ultrasound, and NIPT plus combined with ultrasound. The sensitivity, specificity, FN, FP, PPV, and NPV for each method are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3.

According to Fig. 3A and Table 3, for T13, T18, and T21 screening, there was no significant statistical difference in sensitivity and specificity between the four screening strategies (P > 0.05). The PPV of NIPT and NIPT combined with ultrasound significantly higher than NIPT plus and NIPT plus combined with ultrasound. Sensitivity, specificity and NPV were 100% across all methods, except for NIPT alone, which demonstrated a slight reduction. This suggests that negative results from these screening methods can be better excluded for T13, T18, and T21.

Figure 3B and Table 3 illustrates the performance of different screening tools for detecting SCA, MMS, and RAT. Notably, the data for NIPT is based on cases that met the supplementary reporting criteria in our hospital. There was no significant statistical difference in sensitivity and specificity between NIPT plus and NIPT and between NIPT plus with ultrasound and NIPT with ultrasound. However, the sensitivity of NIPT plus with ultrasound was significantly higher than that of NIPT plus (P < 0.05). Otherwise, NIPT plus with ultrasound showed higher NPV and PPV than NIPT plus for detecting SCA, MMS, and RAT. This indicates that the combination of NIPT plus and ultrasound can greatly increase the detection of chromosomal abnormalities (SCA, MMS, and RAT). However, NIPT showed better PPV than NIPT plus, likely due to the supplementary reporting criteria for NIPT requiring cfDNA > 10%, whereas NIPT plus only requires > 5%.

In the screening for T13/18/21, all methods had an FN rate of 0, except for NIPT, which had a higher FN rate of 12.5%, potentially due to low fetal cfDNA concentration or inherent limitations in detection sensitivity. In the screening for SCA, MMS, and RAT, NIPT had a significantly higher FN rate of 71.4%, while NIPT plus also exhibited a relatively high FN rate of 64.7%, indicating potential technological limitations in these methods. However, NIPT plus combined with ultrasound achieved the lowest FN rate (11.8%), demonstrating that this method is the most effective in minimizing false negatives.

Regarding FP, NIPT and NIPT combined with ultrasound had the lowest FP rate (0.99%), whereas NIPT plus and NIPT plus combined with ultrasound had a higher FP rate (7.64%). This could be attributed to the broader detection range of NIPT plus, which increases the likelihood of identifying cases that may not have clinical significance, leading to more false positives. Additionally, ultrasound findings may be influenced by operator experience, and certain transient anatomical variations might be misinterpreted as abnormalities, contributing to an increased FP rate.

In conclusion, combining NIPT plus with ultrasound is the optimal screening strategy, as it significantly reduces FP, minimizes FN, and improves screening accuracy. In prenatal screening, FN is more concerning than FP, as FN can lead to undetected fetal abnormalities, whereas FP cases can be further verified through invasive diagnostic testing. Therefore, the findings of this study further support NIPT plus combined with ultrasound as the most effective screening strategy.

Follow-up of pregnancy outcomes and ultrasonographic findings.

The follow-up results of pregnancy outcomes, NIPT plus results, and ultrasound results are shown in Table 4.

No T13 NIPT plus positive results in collected patients. The termination of pregnancy rate (TOP) was 100% for both T18 and T21 TP cases. The TOP rate in all SCA TP cases was 25%. The TOP rate for MMS TP was 0%. For RAT cases, TOP rates were 20% for FP and 100% for FN. We found that the two RAT FN cases screened by NIPT plus were all chromosome 22 abnormalities. Of the 5 RAT FP screened by NIPT plus, 3 indicated a high risk of chromosome 7 (60%). Of the 8 MMS screened by NIPT plus, 3 cases (37.5%) were abnormal on chromosome 16 (Table 4). When a fetus is diagnosed with mosaic monosomy X, the pregnant woman typically chooses to proceed with the pregnancy, based on our cohort.

For Table 5, All T18/T21 TP fetuses screened by NIPT had ultrasound abnormalities, but only 1 out of 4 TP from SCA had ultrasound abnormalities, and 75% of the pregnant women chose to give birth to their babies.

One fetus with T21 and T15, misclassified as a FN by NIPT, was stillborn. The detection rate of MMS by both NIPT plus and NIPT remains relatively low, with false negatives being a frequent outcome (Supplementary Tables 1–4). Interestingly, among the MMS FN cases, 8 samples (Table 4) were detectable by NIPT plus, while 9 samples (Table 5) were detectable by NIPT. Notably, most of these FN cases exhibited abnormalities on ultrasound, with G2-structural malformations being the most prevalent finding. This underscores the value of combining NIPT plus with ultrasound to enhance the detection of structural anomalies associated with MMS. Despite some cases being confirmed as MMS through CMA, the majority of pregnant women opted to continue their pregnancies and deliver their babies. These findings highlight the need for improved methodologies in MMS detection using NIPT plus to minimize reliance on ultrasound and reduce the rate of postnatal diagnoses.

Discussion

Our study highlights the limitations of NIPT in detecting Rare Chromosomal Abnormalities (RCAs), particularly in comparison to the standard detection of common trisomies such as T21, T18, and T1323, While NIPT has shown high accuracy for detecting common trisomies, the accuracy rate for RCAs remains insufficient24, as evidenced by the presence of false negative results in our cohort and in previous studies25.

Notably, among the four screening methods evaluated, both NIPT with and without ultrasound showed a false negative case for T21 when screening for trisomy abnormalities (T13, T18, and T21). This aligns with previous reports suggesting higher FN rates for T21 than other trisomies. For example, one study found four FN cases for T21 but only one for T1824. NIPT plus offers advantages over standard NIPT, including expanded test coverage, enhanced detection of CNV, and improved diagnostic accuracy26. Our findings also underscore the potential advantages of NIPT plus, which offers expanded test coverage and enhanced detection of conditions like CNV. However, its clinical utility beyond trisomies 13, 18, and 21 remains controversial due to limited validation data and concerns over FP and FN11, which may lead to unnecessary interventions or missed diagnoses.

NIPT plus benefits a small proportion of the screened population, but it can harm a larger proportion of women who receive FP results, uninterpretable results, or incidental maternal findings. This is because it is important to acknowledge that all pregnant women undergo a detailed ultrasound to screen for fetal anomalies, and a significant proportion of pregnancies affected with a RAT, structural anomaly, or microdeletion will be detected based on ultrasound findings11. Therefore, before promoting the use of NIPT plus, properly designed studies must be conducted to address the clinical utility of NIPT plus.

The primary goal of this study was to provide scientific evidence regarding the performance of NIPT plus, with the hope that our findings can contribute valuable insights to the field of prenatal screening and inform clinical practices. At the same time, we hope to find out whether invasive prenatal diagnosis can be avoided directly by NIPT, NIPT plus, and ultrasound, and also to observe whether NIPT and NIPT plus each have different diagnostic efficacies when combined with ultrasound screening.

Our hospital currently offers two types of NIPT testing: the basic version of NIPT and the expanded version, NIPT plus. The basic NIPT focuses on detecting T21, T18, and T13, with other potential autosomal or sex chromosome abnormalities reported in supplementary reports. Moreover, NIPT plus covers a broader range, including T21, T18, T13, additional autosomal aneuploidies, sex chromosome aneuploidies, and 116 types of microdeletion and microduplication syndromes.

One study found that NIPT plus had a 100% detection rate for 5–10 Mb CNV27, which is consistent with the previously published data assay by Pei et al. Their results showed that NIPT detected significantly more PPVs with CNV < 10 Mb than with CNV > 10 Mb28. This discrepancy may be attributed to the limitations in sequencing depth and data volume inherent to both NIPT and NIPT plus, especially when targeting smaller genomic variations. By combining NIPT plus with ultrasound, the detection accuracy for a broader range of chromosomal abnormalities can be significantly improved, highlighting the value of integrating multiple screening methods for comprehensive prenatal diagnosis.

NIPT plus can detect a wider range of potential chromosomal abnormalities compared to NIPT. However, there are concerns that this may lead to an increase in abortions among women. For SCA, MMS, and RAT there is no doubt that NIPT plus presents advantages. NIPT plus combined with ultrasound had the best positive prediction of MMS/SCA. Moreover, MMS abnormalities were most common among chromosome abnormalities in high-risk pregnant women who underwent NIPT plus/NIPT and CMA at the same time in our study. This indicates that improving the diagnostic correctness of MMS and reducing the occurrence of FN is what we need to improve at present. The data indicates that when NIPT plus is available at no extra cost, the majority (73%) of pregnant women choose it over targeted NIPT16. This statement aligns with a previous observation that women place significant importance on receiving information beyond the three classic trisomies29.

In our study, we found that the combination of NIPT plus with ultrasound is the most effective screening strategy, as it completely eliminates FN for T13/18/21 and significantly reduces FN rates for SCA, MMS, and RAT compared to NIPT plus alone, while maintaining high PPV and NPV. This underscores the crucial role of ultrasound in enhancing the detection of chromosomal abnormalities, effectively compensating for the limitations of genetic screening alone. As a result, integrating ultrasound with NIPT plus emerges as the optimal approach for comprehensive prenatal screening.

For SCA/MMS/RAT detection, NIPT plus combined with ultrasound had the highest sensitivity (88.2%) and PPV (92.4%), while its FN rate was the lowest (11.8%). This suggests that ultrasound enhances the detection of chromosomal abnormalities when combined with NIPT plus, effectively minimizing the risk of false negatives. In contrast, NIPT alone had a high FN rate (71.4%), and even NIPT plus without ultrasound exhibited a considerable FN rate (64.7%), highlighting the limitations of genetic screening alone for these conditions.

However, the FP rate was higher for NIPT plus and NIPT plus combined with ultrasound (7.64%) compared to NIPT and NIPT combined with ultrasound (0.99%). This may be due to the broader detection scope of NIPT plus, which increases the likelihood of detecting CNV that do not have clinical significance, leading to more false positives. Additionally, ultrasound findings are subject to operator experience, and certain transient anatomical anomalies may be misclassified as abnormalities, further contributing to an increased FP rate.

FP in NIPT plus can cause significant psychological distress, unnecessary follow-up testing, and even terminations of pregnancy based on uncertain risk assessment. Although NIPT plus expands detection capabilities, its higher FP rate (7.64% for SCA, MMS, and RAT) compared to standard NIPT (0.99%) raises concerns about overdiagnosis and potential harm to patients. This emphasizes the need for improved pre-test counseling to ensure that patients fully understand the limitations of NIPT plus and the likelihood of false positive results.

Additionally, ethically, the increased FP rate means that some women may undergo unnecessary invasive procedures (e.g., amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling), exposing them to potential risks without clear benefits. Given that FPs disproportionately affect conditions beyond common trisomies (e.g., SCA and MMS), it is critical to establish stricter post-test validation protocols to minimize unnecessary interventions.

To mitigate the impact of false positives, clinical guidelines should incorporate a tiered approach, where positive NIPT plus results for rarer abnormalities are further validated through high-resolution ultrasound or additional molecular testing before recommending invasive diagnostic procedures.

The PPV of NIPT plus or NIPT combined with ultrasound for SCA/MMS/RAT was elevated, with the highest PPV observed in NIPT plus combined with ultrasound. This highlights the limitations of using NIPT plus alone, as it relies solely on fetal cfDNA analysis and may fail to detect certain chromosomal abnormalities, particularly those with low fetal fraction or mosaicism. These findings suggest that NIPT plus alone may not be sufficient for comprehensive detection, reinforcing the need for ultrasound as a complementary tool to improve diagnostic accuracy. A study revealed that late first-trimester ultrasound (LFTU) after a high-risk NIPT result can alter the PPV for many chromosomal abnormalities, assisting counseling regarding invasive prenatal testing and pregnancy management30.

Given the NPV of 98.7% for NIPT plus combined with ultrasound, we believe that NIPT plus is the safer choice for patients suspected of having SCA, MMS, or RAT. However, due to the risk of false positives and the potential for operator-dependent misinterpretation in ultrasound screening, we emphasize that regular follow-up ultrasounds remain crucial after NIPT or NIPT plus screening rather than relying solely on a single screening method. This multimodal approach ensures a more comprehensive and accurate risk assessment, minimizing both false negatives and false positives.

In terms of pregnancy outcomes, we found a higher level of acceptability for SCA and MMS. In the SCA-TP group, only 2 pregnant women chose to terminate the pregnancy. In the MMS-TP group, 100% of the women chose to proceed with the pregnancy and give birth to their babies, while most fetuses with other chromosomal abnormalities were selected for termination, which is consistent with previous research31.

Chromosomal anomaly, including submicroscopic CNV, is a major cause of birth defects32. Studies have shown that the proportion of fetuses carrying pathogenic CNV can reach 1.6–1.7%, which is much higher than the prevalence of common fetal trisomies33. Several recent studies have demonstrated the possibility of NIPT plus screening for fetal CNV associated with MMSs34,35, including but not limited to DiGeorge syndrome, Prader–Willi/Angleman syndrome, cri du chat syndrome, and 1p36 deletion syndrome. The performance of the NIPT plus to detect MMS varied widely, with positive predictive values ranging from low (11%–18%) to moderate (29%–77%)35. As a result, the accuracy of NIPT plus in detecting chromosomal abnormalities other than common trisomies remains questionable11. This study revealed that NIPT plus yielded no FN results when screening for routine chromosomal abnormalities such as T13, T18, and T21. However, NIPT plus did generate more FP for SCA, MMS, and RAT compared to NIPT. This finding aligns with the notion that NIPT plus is better suited for screening chromosome microdeletions and microduplications. We found that the two RAT FN cases screened in NIPT plus were all due to abnormalities in chromosome 22. Cases of trisomy 22 often present with several severe deformities, including failure to thrive, hypotonia, pre-auricular sinus, low set ears, hypertelorism, posterior low hairline, micrognathia, cleft palate, congenital heart disease, imperforated anus with anovulvar fistula, contracted pelvis and bilateral rocker-bottom feet, and they rarely survive to term36. Research has discovered that the presence of mosaic trisomy 22 during amniocentesis in pregnancy can lead to facial clefts, oligohydramnios, and FGR37. Our two cases of FN RAT showed stillbirth and FGR. However, as the test specimens we chose to use for CMA confirmation in these two FN cases were aborted chorionic villi and amniotic fluid, respectively, and no CMA was done on placenta specimens, we were unable to rule out the possibility that fetal abnormalities could be associated with placental abnormalities. This indicates that further refinement of ultrasound diagnoses can help avoid FN screening results and allow pregnant women to avoid invasive prenatal diagnostics. Of the five RAT and FP detected by NIPT plus, three indicated a high risk of chromosome 7 (60%). Of the 8 MMS screened by NIPT plus, 3 cases (37.5%) were abnormal on chromosome 16. This means that if the screening capabilities of NIPT plus for chromosome abnormalities on chromosomes 7 and 16 can be improved, the number of false-positive cases in RAT and MMS can be significantly reduced. This would provide more accurate results and potentially minimize the need for further invasive diagnostic procedures.

According to the prenatal diagnosis guidelines released in 2016, it is recommended that all pregnant women be provided with prenatal aneuploidy screening testing, regardless of maternal age and other risk factors38. Studies have shown that NIPT plus is recommended as the first choice for fetal diagnosis for pregnant women with 2.5 mm ≤ NT < 3.0 mm and who do not accept invasive prenatal diagnosis39. Another study recommended NIPT plus for pregnant women with NT thickening of 95th percentile-3.0 mm first40. These studies indicate that it is necessary to perform NIPT/NIPT plus testing when a certain abnormal parameter of the ultrasound is within a critical range. We understand that ultrasound requires a high level of expertise from medical professionals and is subject to subjective influences, which is why it is imperative to further expand the application of combined diagnosis using both ultrasound parameters and NIPT/NIPT plus. Further subdividing or scoring abnormal parameters and providing recommendations for invasive prenatal testing based on these results, can significantly reduce harm to pregnant women.

Economic analysis from a social perspective of pregnant women in China has shown that introducing NIPT as a screening strategy for Down syndrome is more cost-effective than using the second-trimester triple screening method41. For conditions such as SCA, RAT, and MMS, NIPT plus is undoubtedly the preferred option for primary screening. However, if we can utilize ultrasound indicators or other lower-cost blood tests to identify the risk of RAT, MMS, SCA, or common chromosomal abnormalities, and then advise pregnant women on whether to opt for NIPT plus or NIPT, it could significantly reduce the financial burden on patients and the healthcare system.

One major limitation of our study is its retrospective design, which may introduce selection bias. Cases included in the study were based on historical patient data, meaning that the clinical context in which NIPT plus was recommended may differ from real-world settings where more diverse screening options are available.

Another limitation is the generalizability of our findings. Our data is derived from a single-center study, limiting the ability to extrapolate results to broader populations, particularly those with different ethnic backgrounds, healthcare access, or prenatal screening preferences. Future studies should include larger, multi-center cohorts to validate the clinical efficacy of NIPT plus in diverse populations.

Additionally, we recognize that the accuracy of NIPT plus depends on factors such as sequencing depth and fetal fraction, which were not fully accounted for in our study. Given the variability in laboratory methodologies, standardized guidelines for reporting NIPT plus results are necessary to ensure consistent clinical interpretation.

To improve clinical recommendations, further prospective studies should be conducted to evaluate the long-term clinical utility of NIPT plus, particularly in detecting rare aneuploidies and CNV. Additionally, enhanced patient counseling strategies should be implemented to address the ethical concerns of false positives and reduce unnecessary anxiety or invasive procedures. Moreover, guidelines should be refined to optimize the integration of ultrasound with NIPT plus, ensuring that positive findings undergo additional validation before informing clinical decisions.

Conclusion

-

1.

NIPT plus with Ultrasound: Combining NIPT plus with ultrasound improves detection accuracy for rare conditions like RAT, MMS, and SCA. This approach is recommended for comprehensive screening, especially for rare chromosomal abnormalities.

-

2.

SCA Detection: Both NIPT and NIPT plus with ultrasound achieved 100% detection for SCA. Either approach should be used for SCA screening.

-

3.

Screening for T13/18/21: For common trisomies (T13, T18, and T21), combining ultrasound with NIPT plus resulted in 100% detection rates. NIPT plus combined with ultrasound is recommended as an initial screening method for these trisomies, as it ensures complete detection while maintaining high sensitivity and PPV.

-

4.

Reducing FN: Ultrasound reduces false negatives, particularly for MMS and RAT, which NIPT plus alone may miss.

-

5.

Tailored Approach: A personalized screening strategy is essential to balance the strengths and limitations of NIPT and NIPT plus, guided by individual risk profiles.

In conclusion, NIPT plus combined with ultrasound is the most effective approach for comprehensive prenatal screening.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher. You can contact the corresponding author for data access (yanjh27@mail.sysu.edu.cn).

References

Zhao, C. et al. Detection of fetal subchromosomal abnormalities by sequencing circulating cell-free DNA from maternal plasma. Clin Chem. 61(4), 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.233312 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing for trisomies 21, 18 and 13: Clinical experience from 146,958 pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 45(5), 530–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14792 (2015).

Mei, L., Tang, Q., Sun, B. & Xu, L. Noninvasive prenatal testing in China: Future detection of rare genetic diseases?. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 3(3), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.5582/irdr.2014.01012 (2014).

Haghiac, M. et al. Increased death of adipose cells, a path to release cell-free DNA into systemic circulation of obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20(11), 2213–2219. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.138 (2012).

Zozzaro-Smith, P., Gray, L. M., Bacak, S. J. & Thornburg, L. L. Limitations of aneuploidy and anomaly detection in the obese patient. J Clin Med. 3(3), 795–808. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm3030795 (2014).

Budis, J. et al. Combining count- and length-based z-scores leads to improved predictions in non-invasive prenatal testing. Bioinformatics 35(8), 1284–1291. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty806 (2019).

Benn, P., Cuckle, H. & Pergament, E. Non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy: Current status and future prospects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 42(1), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12513 (2013).

Bianchi, D. W. et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing and incidental detection of occult maternal malignancies. JAMA 314(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.7120 (2015).

Gregg, A. R. et al. Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: A position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 18(10), 1056–1065. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.97 (2016).

Benn, P. et al. Position statement from the chromosome abnormality screening committee on behalf of the board of the international society for prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 35(8), 725–734. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4608 (2015).

Christiaens, L., Chitty, L. S. & Langlois, S. Current controversies in prenatal diagnosis: Expanded NIPT that includes conditions other than trisomies 13, 18, and 21 should be offered. Prenat Diagn. 41(10), 1316–1323. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5943 (2021).

Bedei, I., Wolter, A., Weber, A., Signore, F. & Axt-Fliedner, R. Chances and challenges of new genetic screening technologies (NIPT) in prenatal medicine from a clinical perspective: A narrative review. Genes (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12040501 (2021).

Wellesley, D. et al. Rare chromosome abnormalities, prevalence and prenatal diagnosis rates from population-based congenital anomaly registers in Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 20(5), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2011.246 (2012).

Skuse, D., Printzlau, F. & Wolstencroft, J. Sex chromosome aneuploidies. Handb Clin Neurol. 147, 355–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-63233-3.00024-5 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Performances of NIPT for copy number variations at different sequencing depths using the semiconductor sequencing platform. Hum Genomics. 15(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-021-00332-5 (2021).

van der Meij, K. R. M. et al. TRIDENT-2: National implementation of genome-wide non-invasive prenatal testing as a first-tier screening test in the Netherlands. Am J Hum Genet. 105(6), 1091–1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.10.005 (2019).

Xie, X. et al. Diagnostic cytogenetic testing following positive noninvasive prenatal screening results of sex chromosome abnormalities: Report of five cases and systematic review of evidence. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8(7), e1297. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.1297 (2020).

Martin, K. et al. Clinical experience with a single-nucleotide polymorphism-based non-invasive prenatal test for five clinically significant microdeletions. Clin Genet. 93(2), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.13098 (2018).

Practice Bulletin No. 175: Ultrasound in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 128(6), e241–e256. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001815 (2016).

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 204: Fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol. 133(2), e97–e109. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000003070 (2019).

Tian, Y. et al. Analysis of the accuracy of Z-scores of non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal Trisomies 13, 18, and 21 that employs the ion proton semiconductor sequencing platform. Mol Cytogenet. 11, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-018-0397-x (2018).

Junhui, W. et al. Evaluation of the Z-score accuracy of noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal trisomies 13, 18 and 21 at a single center. Prenat Diagn. 41(6), 690–696. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5908 (2021).

Juvet LK, Ormstad SS, Stoinska‐Schneider A, Solberg B, Arentz‐Hansen H, Kvamme MK, Fure B. NIPH Systematic Reviews: Executive Summaries. Non-Invasive Prenatal Test (NIPT) for Identification of Trisomy 21, 18 and 13. Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) Copyright © 2016 by The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH). 2016

Xue, Y. et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing to detect chromosome aneuploidies in 57,204 pregnancies. Mol Cytogenet. 12, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-019-0441-5 (2019).

Dai, P. et al. Is it necessary to choose NIPT-plus for pregnant women who opt for non-invasive prenatal testing? A study of 50 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi 38(9), 895–899. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn511374-20200619-00456 (2021).

Xue, H. et al. Efficiency of expanded noninvasive prenatal testing in the detection of fetal subchromosomal microdeletion and microduplication in a cohort of 31,256 single pregnancies. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 19750. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24337-9 (2022).

Tian, W. et al. Evaluation of the clinical utility of extended non-invasive prenatal testing in the detection of chromosomal aneuploidy and microdeletion/microduplication. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28(1), 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01285-2 (2023).

Pei, Y. et al. Efficiency of noninvasive prenatal testing for the detection of fetal microdeletions and microduplications in autosomal chromosomes. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8(8), e1339. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.1339 (2020).

Beulen, L. et al. Women’s and healthcare professionals’ preferences for prenatal testing: a discrete choice experiment. Prenat. Diagn. 35(6), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4571 (2015).

Scott, F. et al. Late first-trimester ultrasound findings can alter management after high-risk NIPT result. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 62(4), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.26272 (2023).

Yuan, X., Yong, W., Dai, L., Wang, W. & Wu, L. The role of non-invasive prenatal testing and ultrasound in prenatal screening of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in singleton: A retrospective study. Ann. Transl. Med. 11(2), 111. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-22-6343 (2023).

Webber, D. M. et al. Developments in our understanding of the genetic basis of birth defects. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 103(8), 680–691. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23385 (2015).

Evans, M. I., Wapner, R. J. & Berkowitz, R. L. Noninvasive prenatal screening or advanced diagnostic testing: Caveat emptor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 215(3), 298–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.029 (2016).

Liang, D. et al. Clinical utility of noninvasive prenatal screening for expanded chromosome disease syndromes. Genet. Med. 21(9), 1998–2006. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0467-4 (2019).

Shi, P. et al. The potential of expanded noninvasive prenatal screening for detection of microdeletion and microduplication syndromes. Prenat. Diagn. 41(10), 1332–1342. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.6002 (2021).

Lean, S. F., Lin, S. P., Shen, E. Y., Ho, M. Y. & Yang, S. Y. Liveborn trisomy 22: report of one case. Zhonghua Min Guo Xiao Er Ke Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 33(3), 226–230 (1992).

Chen, C. P. et al. Mosaic trisomy 22 at amniocentesis: Prenatal diagnosis and literature review. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 58(5), 692–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2019.07.020 (2019).

Practice Bulletin No. 162: Prenatal Diagnostic Testing for Genetic Disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 127(5), e108–e122. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001405 (2016).

Xie, X., Zhou, H., Zhao, Q., Lu, Y. & Meng, Y. Application of expanded noninvasive prenatal test in prenatal diagnosis of fetuses with increased nuchal translucency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 35(25), 6213–6218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.1909564 (2022).

Ji, X. et al. When NIPT meets WES, prenatal diagnosticians face the dilemma: genetic etiological analysis of 2328 cases of NT thickening and follow-up of pregnancy outcomes. Front. Genet. 14, 1227724. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1227724 (2023).

Shang, W., Wan, Y., Chen, J., Du, Y. & Huang, J. Introducing the non-invasive prenatal testing for detection of Down syndrome in China: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open 11(7), e046582. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046582 (2021).

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 82001564).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: Shaobin Lin, Peisong Chen; Performing the experiments: Meilin Chen, Jinghai Yan, Siyang Yu, Lu Ai, Xuegao Yu, Ruizhi Wang; Acquisition and analysis of data: Meilin Chen, Jinghai Yan; Data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript: Meilin Chen, Jinghai Yan, Peisong Chen, Shaobin Lin. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University [(2021)210–2]. The studies were conducted following the local legislation and institutional requirements. We confirmed that the study complies with all regulations. Human samples used in this study were acquired from primarily isolated samples as part of our previous study for which ethical approval was obtained. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin following the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Chen, P., Yu, S. et al. Retrospective study on NIPT or NIPT plus combined with ultrasound in screening fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Sci Rep 15, 12859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97230-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97230-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ultrasound and genetic findings in a case series of fetuses presenting vertebral defects

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2025)