Abstract

The current increase in large wildfires is a socio-economic and ecological threat, particularly in populated mountain regions. Prescribed burning is a fuel management technique based on the planned application of fire to achieve land management goals; still, little is known about its potential impacts on tree physiology and soil properties in the European Alps, where it has never been applied. In spring 2022, we tested the effects of prescribed burning for fire hazard reduction in a dry conifer forest dominated by Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). We generated an intensity gradient by manipulating surface fuels at the base of selected trees and evaluated prescribed burning effects on branch hydraulic conductivity, wood anatomy and soil physico-chemical properties in the short- and mid-term, up to one year after the treatment, with controls outside the treated area. The results showed that prescribed burning led to an effective surface fuel load reduction, and the plant-soil system was resistant, despite being affected by a considerable lack of rainfall. We conclude that even a high-intensity prescribed burning can be considered sustainable for reducing fire hazard in Scots pine forests of the European Alps, with these findings being extendable to similar forest ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Managing large and severe wildfires is one of the main challenges of our times1, especially in populated mountain regions where these fires can affect human settlements and trigger secondary disturbances2,3. In the European Alps, extreme fire events are becoming recurrent4 due to weather extremes and flammable fuels availability over large surfaces, i.e., fuel build-up5, with negative consequences on many forest ecosystems services6.

Fuel management is an effective strategy to mitigate wildfires spread under extreme weather conditions7; it includes variable retention harvest, selective thinning, and prescribed burning (PB)8. PB is defined as the planned application of fire to wildland vegetation under prescribed environmental conditions7, and has been increasingly used in dry conifer forests to mitigate fire severity and potential crown fires9. PB heat intensity and duration must be dosed appropriately10, also in function of specific plant traits, such as bark thickness, to achieve the desired effects (e.g., fuel consumption) while avoiding damaging the trees and the underlying soil.

The heat released from a fire can significantly influence trees and their hydraulic systems, cambium survival, wood anatomy, and can cause crown scorch11. Heated plumes can cause massive water losses from the leaves (i.e., inducing a lower water potential12), leading to an increase in water tension within the xylem conduits (vessels and tracheids), resulting in air bubbles intrusion (cavitation), water column ruptures, and emboli formation13,14, eventually causing desiccation and tree death11. Mortality and high scorching are not unlikely with PB application15. Fire heat can also induce deformations in xylem vessel walls and make trees more vulnerable to embolism formation16. Several damages to stem cambium and tracheids have been observed in conifers (Picea abies (L.) H.Karst and Pinus sylvestris L.) and vessel cell walls disruption in broadleaves (Fagus sylvatica L.)17. Finally, fire can reduce tree crown volume, allowing the remaining leaves to potentially access a greater water availability, resulting in the formation of new xylem cells with larger lumen area and thicker walls18, or leading to an overall decrease in tree-ring width (TRW) in the years following a fire19.

PB can induce effects similar to those of a wildfire. Macroscopic effects like scorching (on stem and branches) can be recorded immediately after the treatment, while effects on plant physiology and anatomy can be observed at later times (in the short, medium and long term). For example, in the short term (< 6 months after the fire), a decrease in sap flux density was observed in both two-year-old Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex C. Lawson trees treated with a 1.4 MJ m2 fire dose20 and Pinus halepensis Mill. trees at the pole stage (mean diameter = 5.4 cm; mean height = 4.7 m) heated at 250 °C for ca. 60 s21. However, no differences in hydraulic conductivity and stem water potential between treated and control plants were observed20,21. In the medium term (between 6 and 18 months after fire), no greater incidence of embolism nor changes in wood anatomy (i.e., cell lumen area and wall thickness, tree ring width) were found in mature stands of Pinus pinea L. treated with a high PB intensity (above 300 °C for a mean residence time of 165 s)22, and no traumatic resin ducts were detected in 75-year-old Pinus pinaster Aiton trees following a PB with a 43–304 kW m-1 fireline intensity range23. In the long term, 3 years after a PB, on the basis of wood anatomy (tree ring width, and latewood and earlywood abundance), Pinus sylvestris L. was found to be more resistant and less resilient than Pinus nigra when exposed to temperatures above 120 °C for a mean residence time of 540s24.

Fire can change soil properties by both direct exposure to high temperatures or by indirect consequences. Temperatures up to 700 °C can be reached at the ground surface25, and given the low soil thermal conductivity, high temperatures are limited to the first centimeters of topsoil26,27, where soil experiences a general decrease in organic carbon (C) content due to soil organic matter (OM) combustion28,29, loss of soil structure and aggregation30,31, increase in water repellency (WR)32, and detrimental effects on soil microfauna30,33. Extensive incineration of canopy covers can lead to bare soil exposure over large areas and increased erodibility and erosion28. PB-treated areas can display signs of soil structure fragmentation34, organic C loss35, and enhanced WR36.

In European countries with a Mediterranean climate, PB has been in use in dry conifer forests since the 1980s, achieving a remarkable fire hazard mitigation37. Recently, PB has been increasingly applied also in European conifer forests growing in different climates38, and the effects of PB have been investigated in Finland39, Sweden40, Portugal41, Spain42, Germany43, France44 and Italy22,45. Still, to date, no experiments have ever been conducted in the European Alps, and the potential impacts of PB on native trees and soils remain unknown. In these environments, Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) is often the dominant species, and its resistance traits to surface fires are well-documented: thick bark, high crown insertion height, and a deep root system46. However, compared to other species of the Pinus genus, Scots pine is known to be less resistant to both wildfires47 and PB24. At the same time, soil aggregation in the Alps is mainly bound to the presence of OM, and once OM undergoes combustion aggregation can decrease48, and soil erodibility increases. As the European Alps are also characterized by a harsh topography that determines high post-fires erosion yields49, PB application must consider the possible fragility of this environment.

In this study, we inquired about the sustainability of PB as a fire hazard reduction practice in conifer forests of the European Alps, and assessed its effects on a representative plant-soil system (Scots pine forest). We hypothesized that an effective treatment would reduce fuel load and cause only minor or transient drawbacks to plant hydraulic conductivity, wood anatomy (cambium mortality, xylem cells modification) and soil properties (loss of topsoil OM, soil fragmentation and increase of WR). We thus applied two increasing fuel loads to obtain a fire gradient and evaluated the effects of PB in both the short- and mid-term, up to one year after the prescribed burning.

Results

Fuel consumption and heating treatment

Burned plots experienced an effective fuel load consumption of 51% (Table 1). At the stem base, the average maximum temperature was 568 ± 249 °C, while it was 378 ± 363 °C at the surface of the soil mineral horizon (Table 1).

Based on the ratio between the critical time for cambium kill (τc) and duration of lethal heat (τL) trees with τc/τL < 7 were identified as those that experienced a high level of heating treatment (high-intensity), while the others were assigned to the low treatment level (Plant intensity level in Table 1). Only in two cases (plot No. 2 & 11) the intensity experienced by the plants (Table 1) differed from the planned intensity (Fig. 1), likely due to the stochasticity of the combustion process. Overall, the plots where the trees experienced a higher intensity were also those where more fuel was consumed (25.5 ± 9.0 vs. 15.1 ± 4.5 Mg ha-1, with 59% vs. 42% average fuel consumption). The selected plants (tree parameters in Supplementary Table S1) displayed an average stem scorch height of 0.9 ± 0.3 m and were exposed to a range of reaction intensities of 168–659 kW m-2 (342 ± 146 kW m-2, Supplementary Table S2).

The intensity at the soil level (Soil intensity level in Table 1, assessed by ash color) was in overall agreement with the intensity at stem level (Plant intensity level, Table 1). In the high-intensity plots, the topsoil reached an average maximum temperature of 478 ± 363 °C, while it reached 278 ± 411 °C in the low-intensity plots, with a wide variability (p > 0.05).

Effects on tree physiology

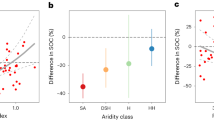

In the short- and mid-term (one, six and twelve months after PB, t1, t2 and t3), branch xylem-specific hydraulic conductivity (Khx) did not significantly differ between control and treated plants (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2a). One month after the treatment, the Khx was 55% higher than during the other two sampling periods, highlighting a significant time-related effect (p < 0.001).

Measurements of (a) branch hydraulic conductivity (Khx) and (b) stem water potential (ψstem) at time t1 (1 month after PB), t2 (6 months after PB) and t3 (12 months after PB). Diverse colors signify distinct plant burn intensity levels. Effects were tested according to Treatment (T), time (t) and Treatment:time interaction (T:t). Stars (* for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001) and letters according to statistically significant differences in mean values.

Unlike Khx, stem water potential (ψstem) was similar across all the three times (p > 0.05), as well as between control and treated trees (p > 0.05). The average ψstem was -0.06 ± 0.02 MPa for t1, -0.10 ± 0.08 MPa for t2 and -0.13 ± 0.10 MPa for t3 (Fig. 2b).

Water stress tolerance of PB-treated and control plants was tested six and twelve months after PB and, as expected, the Khx decreased (Supplementary Fig. S1a and S1c) as water stress increased (Supplementary Fig. S1b and S1d). For each ψstem interval considered, the Khx of control and treated trees was not significantly different (p > 0.05), both at t2 and t3.

Effects on wood anatomy and formation of traumatic resin ducts

Observations of transversal and radial microsections revealed no morphological modifications in stem and branch wood for the tree-ring before and after PB-treatment (Fig. 3). In particular, pre-PB tree-ring tracheids (2021, t0) were normally shaped, without any roughness, breakage or graininess of the internal surface, no wavy cell walls or collapses (Fig. 3a, 3c). The post-PB tree-ring tracheids (2022, t3) were equally well-shaped and sized (Fig. 3b and 3d).

Wood core tree-rings and branch resin ducts: transversal microsection of (a) t0 and (b) t3 wood core ring (20X magnification); radial microsection of (c) t0 and (d) t3 wood core ring (40X magnification); (e) transversal microsection of a branch (4X magnification); (f) detail of resin ducts present on branch transversal microsection (20X magnification).

We found a wide individual variability in all the anatomical parameters (Table 2); only the stem wood tracheid wall thickness (wt) was significantly different according to time (t0 vs. t3, p < 0.001) and Treatment:time interaction (p < 0.001): at t3, wall thickness of control and high-intensity treated plants was significantly thinner (-8% and -20%) than at t0, while the wall thickness of low-intensity treated plants was 12% thicker. No differences were observed between PB-treated and control plants in terms of lumen area (LA), tree-ring width (TRW), and theoretical hydraulic conductivity (Khtheor) measured at both t0 (2021) and t3 (2022) (p > 0.05). Data of Khtheor measured at t3 confirmed the results obtained from branch hydraulic conductivity measured twelve months after PB (Fig. 2a). No evidence of increased resin ducts formation was observed (Fig. 3e, 3f), as the total number of resin ducts (nRD of stem and branches wood) and their total area (AtotRD of stem and branches) did not significantly differ by Treatment or time (p > 0.05 for both).

Litter transformations

A significant decrease in litter (L) content occurred in the short-term (t1) in plots that experienced the greatest PB intensity (p < 0.01, Fig. 4a, t1 vs. t0). In the mid-term (t2, t3), the amount of litter decreased in all the samples, also in the controls, with a significant effect of time (p < 0.001), and no effect of treatment (p > 0.05) or of Treatment:time interaction (p > 0.05).

Litter (a) content (Mg ha-1) and b) composition depicted on van Krevelen diagrams (H/C vs. O/C molar ratios). Time of sampling: t0 (2 months before PB application), time t1 (right after PB application, within the day), t2 (6 months after PB) and t3 (12 months after PB). Diverse colors signify distinct soil burn intensity levels. Effects were tested according to Treatment (T), time (t) and Treatment:time interaction (T:t). Stars (* for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001) and letters according to statistically significant differences in mean values.

At t0, the litter composition was fairly homogeneous across the plots, with H/C ratios around 1.5 and O/C ratios ranging from 0.3 to 0.6 (Fig. 4b, panel t0). In the day of PB, the elemental composition of litter of high-intensity plots shifted towards lower H/C and O/C ratios (Fig. 4b, panel t1), and recovered after six months (t2), reaching pre-treatment values (Fig. 4b). One year after PB (t3), litter composition remained mostly unaltered in terms of H/C ratios, while a higher variability was visible in terms of O/C (Fig. 4b panel t3 vs. t2). Litter C/N was significantly different between controls and high-intensity plots at t1 (65 vs. 45, p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S2a), and significantly higher in autumn 2022 (t2).

Organic horizon transformations

The average thickness of the organic (O) horizon was always around 3–4 cm in the control plots (Fig. 5a), and experienced far less fluctuations than the L horizon (Fig. 4a). Treatment significantly influenced the thickness of the O (p < 0.05), while there was no significant effect of time (p > 0.05), nor of the Treatment:time interaction (p > 0.05).

Organic horizon (a) thickness (cm), (b) composition depicted on van Krevelen diagrams (H/C vs. O/C molar ratios), (c) moisture (%) and (d) water repellency (expressed by the Water Drop Penetration Time test, s). Time of sampling: t0 (2 months before PB application), t1 (right after PB application, within the day), t2 (6 months after PB) and t3 (12 months after PB). Diverse colors signify distinct soil burn intensity levels. Effects tested according to Treatment (T), time (t) and Treatment:time interaction (T:t). Stars (* for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001) and letters according to statistically significant differences in mean values.

Before PB application (t0), the elemental composition of the organic horizon was highly variable in the study area (Fig. 5b, panel t0), both for O/C and H/C ratios. After PB (Fig. 5b, panel t1), the variability decreased, with all the O horizons displaying a fairly homogeneous H/C value, and O/C ranging between 0.2 and 0.6. After six months, the composition of the O horizon was again highly variable (Fig. 5b, panel t2) and after twelve months (Fig. 5b, panel t3) the composition was similar to the one of t1. There was no significant effect of Treatment, time, or their interaction on the O/C molar ratio (p > 0.05 for all), while the H/C molar ratio was significantly higher at t0 and t2 (p < 0.01). The C/N ratio of the O horizon (Supplementary Fig. S2b) was lower than the C/N of the litter layer (Supplementary Fig. S2a), and did not display any difference according to either Treatment, or time, or their interaction (p > 0.05).

The O horizon moisture (Fig. 5c) significantly changed with time (p < 0.001), with the lowest values detected at t0, during a dry period, and the highest values at t2, in autumn 2022. A significantly higher water repellency was recorded in control sites (Fig. 5d), with average infiltration times corresponding to strongly- and extremely-hydrophobic50. The hydrophobicity of the O horizon changed according to both time and Treatment (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively), decreasing from t0 to t1 both in the controls and in the treated sites (Fig. 5d) and at t3 the values were around 3–4 times higher than at t0 in all the areas.

Topsoil transformations

Soil pH ranged between 6.1 and 7.8, as expected from the presence of calcareous rocks. Differences in pH existed already at t0 for plots that would experience different treatments (Fig. 6a, p < 0.01). The pH was overall higher at time t2 with respect to t0 and t1 (p < 0.01 for time effect), with no significant Treatment:time interaction (p > 0.05). Soil electrical conductivity (EC), as pH, differed already at t0 for areas that would experience different treatments (p < 0.05, Fig. 6b). The EC peaked at t1 in all the plots, with significantly higher values with respect to the other sampling times (p < 0.001, Fig. 6b).

Mineral topsoil (a) pH, (b) EC (μS cm-1), (c) size fraction composition (abundance of macro and micro fraction, %) (d) water repellency (expressed by the Water Drop Penetration Time test, s), (e) soil moisture (%), (f) OC content (g 100 g-1), (g) C/N ratio. Time of sampling: t0 (2 months before PB application), t1 (right after PB application, within the day), t2 (6 months after PB) and t3 (12 months after PB). Diverse colors signify distinct soil burn intensity levels. Effects tested according to Treatment (T), time (t) and Treatment:time interaction (T:t); stars (* for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001) and letters according to statistically significant differences in mean values.

The topsoil mostly comprised particles falling in the macro size fraction (Ø > 0.25 mm); the micro size fraction (Ø < 0.25 mm) accounted on average for less than 15%. The macro fraction (Fig. 6c) experienced time-related variations, with significantly lower contents at t2 and t3, both in treated and control plots (p < 0.001).

The topsoil was on average slightly hydrophobic50, with a markedly lower WR than the organic horizons (average infiltration times of 6 vs. 989 s, p < 0.001). The WR of the mineral topsoil was significantly higher at t1 (p < 0.05, Fig. 6d), with no significant differences induced by the Treatment (p > 0.05). The A horizon moisture was significantly lower than the O horizon moisture (average of 17% vs. 44%, p < 0.001), and while the moisture of the O horizon was maximum at t2, in autumn 2022 (Fig. 5c), the moisture of the A horizon peaked at t1 (Fig. 6e), after the spring rain (Supplementary Fig. S3, Fig. S4).

Topsoil organic carbon (C) content displayed a minor increase in the treated plots at t1 (Fig. 6f), with no statistically significant variations, nor in time, nor by Treatment, nor by their interaction (p > 0.05 for all) (Fig. 6f). Topsoil C/N ratio varied according to time of sampling, and was significantly higher at t0 (p < 0.05) with respect to t3 (Fig. 6g).

Discussion

Parameters that changed due to prescribed burning application

The outcomes of our heating treatment (Table 1) agree with existing literature for temperatures reached at stem and soil level22,26 and for fuel consumption4,22. Our PB intervention is in line with the range of reaction intensities observed in prescribed burning interventions in conifer forests51. The slight mismatch between the theorized and the obtained intensity (Table 1vs. Figure 1) can be attributed to microsite variability, experimental conditions and fire stochasticity. Moreover, the point-source nature of the temperature measurements provided by thermocouples may not fully represent the overall condition observed in the field.

In general, fuel load decreased by ca. 51% (Table 1), leading to an effective fire hazard reduction52. At the soil level, the high-intensity plots also displayed a consistent decrease in litter amount (Fig. 4a) and an overall decrease in O horizon thickness (Fig. 5a). Changes in the litter layer elemental composition were observed within the day of PB application in high-intensity plots, with an increase in hydrocarbons (low H/C and O/C, Fig. 4b, panel t1). This suggests the occurrence of intense heat-mediated condensation reactions that led to the combustion-driven loss of labile structures and the selective enrichment in polycyclic aromatic compounds29,53. The high-intensity plots experienced a decrease in the C/N ratio (Supplementary Fig. S2a), and since N has a higher volatilization temperature than C54, it was likely incorporated in thermostable OM fractions29, explaining the lower C/N values. Similar transformations were lacking in low-intensity plots, and in the high-intensity plots they were only transient.

Parameters that did not change with prescribed burning application

Many of the investigated environmental parameters did not change with PB application indicating that: i) the treatment was below the damaging threshold and/or ii) the studied soil–plant system is more resistant than expected.

The controlled magnitude of PB is underlined by the fact that no tree mortality was induced and fire left low scars on the stems. The moderate wind speed detected during PB application tilted the flames, and the plume did not directly invest the crowns of the treated plants, so that there were no differences in water stress levels (stem water potential, Fig. 2b) or growth (tree-ring width, Table 2) between treated and control trees, both in the short- and mid-term15,55,56,57,58. No heat-induced embolism was caused (Fig. 2a), possibly since the fire did not directly invest the branches20. Tracheid wall thickness was similar between treated and untreated plants (Table 2), which is consistent with literature22. At the soil level, minor effects were detected (Fig. 6). A decrease in topsoil organic C content was partially expected, since the topsoil was exposed to temperatures up to 780 °C (Table 1) and even temperatures of 350 °C, if prolonged for more than 3 min, are known to cause substantial organic C losses29. We also expected to detect an alkalinization effect (increase in soil pH and EC in the treated plots) caused by OM combustion and subsequent release of base cations28, which is common after wildfires26,59 and PB35,60. In our experiment, char and ashes covered the ground surface right after PB application (Supplementary Fig. S5), testifying the occurrence of OM combustion, and the slight increase in topsoil organic C in the treated plots at t1 (Fig. 6f) suggest a temporary enrichment in char and ashes in the short-term. A tangible increase in soil water repellency (WR) due to PB was also expected due to the heat-driven condensation of organic compounds on mineral particles61; in similar montane forest soils of the European Alps, this occurs at 200 °C with a 30-min heating time48,62. Evidently the heating experienced by the topsoil due to PB was not sufficiently prolonged to alter the arrangement of OM around soil particles (no significant change in WR, Fig. 6d), nor to induce any disaggregation (Fig. 6c).

Our findings corroborate the fire-resistance traits of Scots pines46,47,63,64,65: stem bark thickness at 30 cm (3.4 ± 1.4 cm) and branch bark thickness (50 ± 8% of branch microsection) provided a substantial thermal insulating layer, while the high branch insertion (3.2 ± 1.0 m on the bole) protected the whole canopy from the heat released by the fire. These adaptations ensured the absence of microscopic deformations in wood structures, which are normally found in non- or lesser-adapted species17. The absence of cambium damages (Fig. 3) confirmed that the temperature reached below the bark was lower than that considered lethal for the cambium (60 °C)66. Consistent with the literature19, unmodified tree-ring width and tracheid lumen area led the theoretical hydraulic conductivity to remain unchanged between treated and controls in the mid-term. Water transport (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. S1) was unaffected by the treatment, likely because the generated heat did not deform any xylem structure11,16. Furthermore, most of the trees had a diameter greater than 17 cm (Supplementary Table S1), which is the threshold above which plants belonging to the Pinus genus are highly resistant to fire67. In fact, there was a lack of traumatic resin ducts formation (Table 2), which is known to occur in response to more intense fires68,69.

Natural variability and changes induced by time

Even before the PB treatment (t0), wood anatomical parameters of stem and branches presented a high variability. Such variability is typically expressed in forest environments70 even under the same climate, and it is due to micro-site and soil properties, and individual genetic variability71.

We can explain this variability considering that the control plots were located uphill (Fig. 1), with a more direct South-ward orientation and in a slightly less steep position (Supplementary Fig. S6a, S6b), with moister O horizons (t0 in Fig. 5c), a mineral topsoil more enriched in organic carbon (t0 in Fig. 6f) and a lower topsoil C/N ratio (t0 in Fig. 6g). The small-scale natural variability likely resulted in a slightly different OM turnover in the two areas (treated vs. control). This hypothesis is supported by the elemental signature of L and O horizons in the study site: while the litter layer composition was almost identical in the two areas (panel t0, Fig. 4b), the composition of the O horizon differed (panel t0, Fig. 5b), with a higher abundance of aromatic compounds (i.e., lower H/C ratios) in the treated plots. These differences in O horizon composition are not attributable to the starting L material, and may be due to the presence of different soil microbial communities impacting OM turnover72, although no specific investigations were carried out. The detected differences in O composition, mirrored by differences in O hydrophobicity (Fig. 5d, control vs. treated plots), were probably exacerbated by the dry phase that preceded t0 sampling, since a homogenization of the O composition was observed after the spring rain (Fig. 5b, panel t1).

In the present experiment, most of the investigated plant and soil properties changed over time rather than with treatment, likely in function of water availability: two separate dry periods struck the study area (from January to July 2022, and in February 2023), and a spring rain fell right before PB application.

During the first dry period (January-July 2022), the meteoric precipitation was 65% lower than the average precipitation historically recorded (2002–2023), and in the second dry period (February 2023) it was 94% lower (Supplementary Fig. S3). Signs of a strong water shortage were visible in the extremely low O horizon moisture content in March 2022 (Fig. 5c). As a consequence, branch hydraulic conductivity declined six and twelve months after PB application (Fig. 2a), both in treated and control plants. The first decline (in autumn 2022) can be attributed to seasonality73 and to the 2022 summer dry period; the second decline (in spring 2023) can be attributed to the 2023 winter dry period (Supplementary Fig. S3). This marked decrease in branch hydraulic conductivity between 2022 and 2023 is in line with the lower amount of litter of 2023 detected in all the plots (Fig. 4a). Together, these evidences seem to point at a drought-driven decrease in ecosystem productivity that invested the Scots pine population as a whole, a hypothesis which is supported by the literature74, and which was noted in 2022 across all the European Alps75.

The spring rain that fell right before PB application (Supplementary Fig. S4) induced a visible recovery of soil moisture in the O (Fig. 5c) and in the A (Fig. 6e) horizons. Rainfall amount was positively related to branch hydraulic conductivity (Supplementary Fig. S7a), which was as well related to air temperature (Supplementary Fig. S7b) and topsoil moisture (Supplementary Fig. S7c), explaining the different hydraulic conductivity values observed at t1, t2 and t3 (Fig. 2). Seasonality and a high global variability were expected, and they are encompassed in fire experiments in the field76.

Implications

The studied soil–plant system is representative of a widespread forest ecosystem77, for wood anatomy78, tree physiology55,71,79, soil properties80 and fuel load81. This representativeness allows us to extend our considerations beyond the borders of the study area.

A lot of existing studies dealing with soil and ecosystem functioning in a post-fire scenario relied on a space-for-time approach31,60,82, and the authors themselves recognized the limitations of this method. In the present investigation, we had the opportunity to follow the evolution of a forest ecosystem over one year, before and after PB application, with controls outside the treated area, so that we could disentangle the role of the treatment from other factors (e.g., climate).

We demonstrated that PB can be sustainably applied in Scots pine formations with 18–50 Mg ha-1 of fuel load, leading to an effective fuel load reduction (by ca. 51%) without compromising tree hydraulics and wood anatomy or soil features in the short- and mid-term, even in the presence of a pronounced dry phase (precipitation 65% lower than the average), which could be even more frequent in the future due to Climate Change83.

Conclusions

This multidisciplinary study is the first to present the results of a PB experiment in the European Alps. PB effectively reduced surface fuel load achieving the desired fire hazard mitigation purposes, the plants resulted highly resistant to PB thanks to thick bark and high crown insertion height, and the fire treatment did not cause any damages to the soil possibly for a low residence time. Water availability was the main driver affecting tree hydraulic conductivity and soil properties during the year of investigation, and plants in the treated plots did not display any signs of a greater stress with respect to the controls. As dry periods are expected to be more frequent in the future due to Climate Change, the success of this experiment in a dry year underlines the applicability of PB even in concomitance with dry phases.

We suggest that future experiments carried out in the European Alps should include considerations regarding: (i) greater treatment intensities, (ii) the application of repeated fires, (iii) the suitability of PB in the longer run beyond one year, and (iv) observations at an even broader scale (more than one location) and more detailed scale (e.g., changes in the very first cm of topsoil and in micromorphological tracheid punctuation structure), so as to fully reconstruct the dynamics of the ecosystem. To conclude, prescribed burning can be considered an ecologically sustainable fuel management practice to be used in strategic areas to mitigate fire hazard in Scots pine forests of the European Alps.

Materials and methods

Site selection

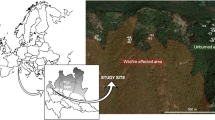

The study site is located in the South-Western European Alps (45.0569 N, 6.7853 E, Fig. 1a, 1b) on a South-facing forested slope, at an elevation of 1600 m asl and with an average slope of 27°. The site is characterized by a warm-summer continental climate with no dry season (Dfb)84, with average annual temperature of 7.0 °C and average precipitation of 645 mm year-1. In 2022, the year of PB application, the study area was exposed to a severe and uncommon dry period (Supplementary Fig. S3). PB was applied in May 2022, after a two-week period in which 45 mm of rain fell (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Scots pine is the dominant species, and forms a monoplanar forest (70% canopy cover) characterized by a stand volume of 290 m3 ha-1 and a mean square diameter of 22 cm. Sporadic individuals of Juniperus communis L. are present, while the herbaceous layer is absent. The area developed on calcschists mixed with serpentinites85, and the soils of the area are mostly classified as Typic Cryorthents (soil map available at https://www.geoportale.piemonte.it/geonetwork/srv/ita/catalog.search#/home).

Sampling design

The PB experiment was performed at one site (N = 1). Within a 1-hectare area, two homogeneous areas were identified: a treated area (T) and a control area (C) (Fig. 1). A total of 18 circular sampling plots were established,12 in the T area and 6 in the C area (Fig. 1c). Each plot (2 m radius) had a tree in its center. We chose trees with a range of diameter classes representative of the entire forest stand, with a crown insertion height low enough to be actually impacted by the fire and also sufficiently low to allow branch collection (tree parameters are reported in Supplementary Table S1). Each plot was sampled for physiological measurements, anatomical measurements and for soil properties according to the experimental design (Fig. 1c, sample type: Plant vs. Plant-and-soil). Samples were collected in the T and in the C area at four different times, in agreement with existing tree physiology and soil monitoring protocols86,87: before PB application (March 2022, t0), after PB application (within the day for fuel and soil properties and one month later for physiological analyses, t1), six months post-burn (November 2022, t2), and twelve months post-burn (May 2023, t3).

Prescribed burning treatment characterization

At the stand level, pre-treatment fuel load and characteristics were assessed at five random points across the T area. At each point, an equilateral triangle composed of three 10 m linear transects was established (i.e., different transects orientations were chosen to avoid any directional bias)88. Along each transect, fuel bed depth, grass height and shrub height were measured at 1 m interval88. According to fuel classification89, the fuel bed included needles and twigs with a diameter < 6 mm (i.e., fuel with a time lag class of 1 h, 1 h fuels), deadwood between 6–25 mm (10 h fuels) and 25–75 mm (100 h fuels). Fuel bed was collected through destructive sampling in three squares of a fixed area (100 × 100 cm2, 1 square along each transect) and oven-dried (for 48 h at 90 °C). Pre-treatment fuel load was on average 26.7 Mg ha-1.

At the plant level, within each T plot (i.e., below the selected trees), a similar smaller equilateral triangle was established, composed of three 2 m linear transects. The pre-treatment fuel load was assessed as above (over a 40 × 40 cm2 fixed area), and fuel load height was measured at 25 cm intervals.

To influence fire behavior characteristics and create a heat exposure gradient, additional fuel doses were placed in each plot of the T area: ca. 10 and ca. 20 Mg ha⁻1 of deadwood (1:1 ratio between 1 and 10 h dry fuel89) for low and high treatment intensities, respectively (Intensity level, Fig. 1c), as visible in Supplementary Fig. S8a, S8b. Fig. S8c displays fire behavior during the prescribed burning treatment.

Thermocouples (K-type, temperature range: 0–1200 ± 4 °C; diameter: 0.4 mm) connected to a datalogger (Hobo-Onset, frequency: 1 Hz) were buried at the tree base, and they were used to measure temperatures at the tree level (30 cm above ground, on the stem, inside a fissure in the bark) and at the soil level (below the organic horizon, at the surface of the mineral topsoil). In the T area, plots belonging to the Plant-and-soil category were equipped with four thermocouples: two thermocouples were placed below the organic horizon, while the other two were placed at the stem base, one upslope and one downslope. For the plots belonging to the Plant category, only the two thermocouples adhering to the bark were used. Thermic sums were calculated for residence times above 200 and 400 °C (Res. Time > 200 °C and Res. Time > 400 °C).

Ignition began with a backfire against wind and slope, followed by point ignitions downslope to minimize the vertical rise in heat flux (plume). Environmental conditions during ignition included average air temperature 22 °C, relative air humidity 55%, five days since the last rainfall, and wind speed at 4.5 km h-1 (Kestrel 5500). Before PB, at the same five random points used to assess pre-treatment fuel load, duff moisture was assessed on a dry mass basis (after oven-drying, 48 h at 90 °C). Average duff moisture was 31 ± 14%. To assess fuel consumption, fuel load was sampled within the T plots at t0 and t1 (right after PB) over a fixed area (40 × 40 cm2) and oven-dried.

Fire intensity and treatment ranking at the tree level

Reaction Intensity (RI) is the heat release per unit area per unit time within the flaming front (kW m-2)90,91. RI was estimated for each selected tree using the First Order Fire Effects Model (FOFEM)92. FOFEM simulates changes in RI through time, both during the flaming front phase and the secondary combustion and glowing combustion phases90. FOFEM allows to customize fuel input and to simulate the desired level of fuel consumption to estimate RI.

For each tree, the measured fuel consumption (Table 1) was subdivided into litter, 1 h fuel, 10 h fuel (in proportions of 0.2, 0.5, 0.3) in the FOFEM model, and the RI of the flaming front phase (grey-shaded area in Fig. S9) was calculated. We were not able to assess fuel consumption in plots No. 4 and 7 before firefighters’ mop-up intervention (Table 1). Therefore, for these two plots, we estimated fuel consumption using the linear relationship between Fuel consum. and the residence time Res. time > 200 °C stem (s) (R = 0.68, p < 0.05); Res. time > 200 °C stem can be considered a proxy of the flaming combustion phase and notably had a positive relation with RI (R = 0.72, p < 0.01).

The ranking of treatment received by each tree was defined according to the conifer mortality model93. The ratio between the critical time for cambial kill (τc) and the duration of lethal heat (τL) was calculated, following Eq. 1 and 293:

where Bt is the bark thickness measured at 30 cm above ground (Table S1);

Higher is the τc/τL ratio, lower is the probability of conifer tree mortality. In our experiment, none of trees displayed a ratio < 1, and the trees were ranked considering a τc/τL, threshold of 7 (high treatment level for values < 7, low treatment level for values > 7).

Physiological and anatomical measurements

Stem water potential and hydraulic conductivity

Live branches (about 1 m long) located upslope at crown insertion height were collected from treated and control trees at three sampling times (t1, t2 and t3). Branches were sampled early in the morning, immediately re-cut under water, covered with a plastic bag and rehydrated with their cut-ends immersed in water. In the lab, a secondary branch was cut under water to obtain a short segment (ca. 4 cm long). The short segment was debarked at one end and connected to a balance (CPA 225D, Sartorius, ± 0.1 mg) by a plastic tube. A filtered 10 mM KCl solution (perfusion solution) was located on the balance in a beaker94. Each branch segment was submerged in a water bath with the water level about 15 cm below the level of the solution on the balance. After a steady flow rate was reached (within a few minutes), the specific branch hydraulic conductivity (Kh) was measured gravimetrically by determining the volumetric flow rate (kg s-1) divided by the pressure gradient (MPa m-1). The Kh was then normalized by the xylem cross-sectional area (m2). Total xylem area was determined using image-processing techniques with ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) on free-hand cross-section images (observed with a light microscope, 2X magnification). The branch xylem-specific hydraulic conductivity (Khx) was calculated as Kh divided by the total xylem area.

Stem water potential (ψx) was measured for each tree using non-transpiring (bagged) brachyblasts. The brachyblasts were placed in a humidified plastic bag covered with aluminum foil for at least 20 min prior to excision and measurement. After excision, samples were allowed to equilibrate for almost 20 min and then stem water potential was determined using a Scholander-type pressure chamber (mod. 1505D, PMS Instruments, OR, USA). Relative branch bark thickness was measured by image processing with ImageJ on the same branches used for hydraulic measurements.

Tolerance to stress-induced xylem dysfunctions was evaluated in terms of differences in branch hydraulic conductivity between treated and control trees by bench dehydration technique79, and both Khx and ψx were measured at increasing time intervals.

Anatomical measurements and calculation of theoretical hydraulic conductivity

The wood anatomical analyses were conducted on the same t3 branches used for physiological analyses and, additionally, on stem wood cores (4 mm diameter) of selected trees sampled at t3. These wood cores were extracted from the stem of 12 (8 treated and 4 control) similar-sized dominant trees (diameter: 20.0 ± 6.7 cm) at a standardized height of 30 cm above ground, upslope22. This sampling was aimed detecting the greatest effect of fire on cambium vitality and anatomical features. The absolute stem total bark thickness was assessed right after sample coring (cm). From 9 out of these 12 plants (6 treated and 3 controls), a 5 cm long branch segment was cut at a fixed 40 cm distance from the main apex. Each branch segment was preserved in a fixative solution (Formalin Free Tissue Fixative, Sigma-Aldrich) and kept at 3–4 °C until sectioning. Radial and transversal microsections (about 20 µm thick) were obtained from both branch segments and stem wood cores using a sliding microtome (Reichert-Jung, Optische Werke AG, Wien, Austria). The microsections were double-stained for 3–5 min with a 1:1 blend of freshly prepared Safranin (1% in distilled water) and Astra Blue (0.5% in distilled water with 0.2% acetic acid)95. The double staining is known to stain in red lignified cell walls, and in blue less-lignified cell walls. Microsections were rinsed with water and ethanol at increasing ethanol concentration (50–75-95%), then embedded in glycerol under a cover glass. Images of the microsections were acquired with a digital camera (CANON EOS700D, Bovenkerkerweg 59, 1185 XB, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) connected to an optical microscope (Olympus CX22LED, Tokyo, Japan). Both radial and transversal microsection images were acquired at 20X magnification and analyzed with ImageJ software. One hundred earlywood tracheids from the annual growth rings of the years 2021 (t0, pre PB application) and 2022 (t3, post PB application) were analyzed. Specifically, tracheid lumen area (LA, μm2), tracheid wall thickness (wt, μm), tracheid diameter (d, μm) and tree-ring width (TRW, μm) were determined. The weighted average of hydraulic diameter (Dh, μm) was calculated following Eq. 3:

where d is the diameter of the n-tracheid14. The theoretical hydraulic conductivity (Khtheor) was also estimated according to the Hagen-Poiseuille equation (Eq. 4):

where Dh is specific for each stem ring and η is the dynamic viscosity of water at 25 °C and atmospheric pressure (8.9 × 10−10 MPa ·s)96.

The total number of resin ducts (nRD) and their average area (Amean duct) were measured. The number of resin ducts was measured on the entire surface of the branch transversal microsections, while the average area was calculated over a constant selected area. Both these parameters were measured separately for the 2021 and 2022 annual rings on wood core transversal microsections. The total area of resin ducts (AtotRD) of each branch and stem cross-section was calculated as (Eq. 5):

Soil characterization

Litter (L), organic (O) and topsoil (A) horizons were collected separately. Each horizon type was assembled from composite samples collected within a 2 m radius inside each plot. An exemplificative mini-pit is visible in Supplementary Fig. S5. In the T area, soil burn severity was visually evaluated after PB application on the basis of ash color97. Litter was collected over a fixed surface (here 10 × 10 cm2), while the O horizon was sampled in terms of thickness (cm). Moisture content was determined gravimetrically on an aliquot of the O and the A horizons, and the remaining material was air-dried and stored at room temperature.

The L and O horizons were milled at 0.5 mm (Ultra Centrifugal Mill ZM 200). The A horizon was sieved at 2 mm; an aliquot was dry sieved to determine the abundance of the macro (Ø > 0.25 mm) and micro (Ø < 0.25 mm) size fractions, while another aliquot was ground at 0.5 mm for further analyses. Water repellency (WR) was evaluated by the Water Drop Penetration Time (WDPT) test on O (0.5 mm milled) and A (2 mm sieved) horizons after having kept the samples in a vacuum chamber for 30 min (room relative humidity was verified to be around 30–50%), recording the water infiltration time of ca. 4 drops of distilled water (0.1 mL)50. The pH and the electrical conductivity (EC) were potentiometrically determined on A horizons (soil:deionized water suspensions of 1:2.5, w/w) after 2 h shaking98. Total carbon (TC) and nitrogen (N) were determined by dry combustion (Unicube CHNS Analyzer, Elementar, Langenselbold, Hesse, Germany) and in mineral horizons organic C (C) content was determined after inorganic C (IC) removal by HCl99. The L and O horizons were analyzed also for hydrogen (H) and sulfur (S) content by dry combustion; an aliquot of these samples was heated in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 5 h to determine its composition on a moisture- and ash-free basis100. The oxygen (O) content was derived by difference. The H/C and O/C molar ratios were then computed and visualized on van Krevelen diagrams101.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with the RStudio software (R version 4.2.3). Before group comparisons, Shapiro–Wilk’s and Levene’s tests were used to check data normality and homoscedasticity; non-normal data were log-transformed. Linear Mixed Models (LMM; “nlme” and “multcomp” packages) were applied to test the effect of treatment (T), time (t), and their interaction (T:t). Where autocorrelation was present, it was included in the model structure; the best model was chosen on the basis of Akaike’s information criterion (AIC). Tukey method (“emmeans” package) was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and p-values were calculated to inspect the relationship between selected variables (“Hmisc” package). The RStudio software was also used to produce boxplots, scatterplots, and stacked bar-plots. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Ingalsbee, T. Whither the paradigm shift? Large wildland fires and the wildfire paradox offer opportunities for a new paradigm of ecological fire management. Int. J. Wildland Fire 26, 557–561 (2017).

Pureswaran, D. S., Roques, A. & Battisti, A. Forest insects and climate change. Current Forestry Rep. 4, 35–50 (2018).

Shakesby, R. A. Post-wildfire soil erosion in the Mediterranean: Review and future research directions. Earth Sci Rev 105, 71–100 (2011).

Brodie, E. G., Knapp, E. E., Brooks, W. R., Drury, S. A. & Ritchie, M. W. Forest thinning and prescribed burning treatments reduce wildfire severity and buffer the impacts of severe fire weather. Fire Ecol. 20, 17 (2024).

Conedera, M. et al. Characterizing Alpine pyrogeography from fire statistics. Appl. Geogr. 98, 87–99 (2018).

Patacca, M. et al. Significant increase in natural disturbance impacts on European forests since 1950. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 1359–1376 (2023).

McWethy, D. B. et al. Rethinking resilience to wildfire. Nat. Sustain. 2, 797–804 (2019).

Müller, M. M., Vilà-Vilardell, L. & Vacik, H. Towards an integrated forest fire danger assessment system for the European Alps. Ecol. Inform. 60, 101151 (2020).

Fernandes, P. M. et al. Prescribed burning in the European Mediterranean Basin. In Global application of prescribed fire) (eds Weir, J. R. & Scasta, D.) (CSIRO Publishing, 2022).

Sparks, A. M. et al. Prefire drought intensity drives postfire recovery and mortality in Pinus monticola and Pseudotsuga menziesii saplings. Forest Sci. 70, 189–201 (2024).

Bär, A., Michaletz, S. T. & Mayr, S. Fire effects on tree physiology. New Phytol. 223, 1728–1741 (2019).

Kavanagh, K. L., Dickinson, M. B. & Bova, A. S. A way forward for fire-caused tree mortality prediction: modeling a physiological consequence of fire. Fire Ecol. 6, 80–94 (2010).

Lens, F. et al. Embolism resistance as a key mechanism to understand adaptive plant strategies. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 287–292 (2013).

Tyree, M. T., Zimmermann, M. H., Tyree, M. T. & Zimmermann, M. H. Hydraulic architecture of whole plants and plant performance. Xylem structure and the ascent of sap 175–214 (2002).

Valor, T. et al. Disentangling the effects of crown scorch and competition release on the physiological and growth response of Pinus halepensis Mill. using δ13C and δ18O isotopes. For Ecol. Manage 424, 276–287 (2018).

Michaletz, S. T., Johnson, E. A. & Tyree, M. T. Moving beyond the cambium necrosis hypothesis of post-fire tree mortality: cavitation and deformation of xylem in forest fires. New Phytol. 194, 254–263 (2012).

Bär, A., Nardini, A. & Mayr, S. Post-fire effects in xylem hydraulics of Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris and Fagus sylvatica. New Phytol. 217, 1484–1493 (2018).

Martin-Benito, D., Beeckman, H. & Canellas, I. Influence of drought on tree rings and tracheid features of Pinus nigra and Pinus sylvestris in a mesic Mediterranean forest. Eur. J. For. Res. 132, 33–45 (2013).

Niccoli, F., Pacheco-Solana, A., De Micco, V. & Battipaglia, G. Fire affects wood formation dynamics and ecophysiology of Pinus pinaster Aiton growing in a dry Mediterranean area. Dendrochronologia (Verona) 77, 126044 (2023).

Partelli-Feltrin, R. et al. Drought increases vulnerability of Pinus ponderosa saplings to fire-induced mortality. Fire 3, 56 (2020).

Ducrey, M., Duhoux, F., Huc, R. & Rigolot, E. The ecophysiological and growth responses of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) to controlled heating applied to the base of the trunk. Can. J. For. Res. 26, 1366–1374 (1996).

Battipaglia, G. et al. Effects of prescribed burning on ecophysiological, anatomical and stem hydraulic properties in Pinus pinea L. Tree Physiol 36, 1019–1031 (2016).

Rodríguez-García, A. et al. Can prescribed burning improve resin yield in a tapped Pinus pinaster stand?. Ind. Crops Prod. 124, 91–98 (2018).

Valor, T. et al. The effect of prescribed burning on the drought resilience of Pinus nigra ssp. salzmannii Dunal (Franco) and P. sylvestris L. Ann. For. Sci. 77, 1–16 (2020).

Rubio, J. L. Spatial patterns of soil temperatures during experimental fires. Geoderma 118, 17–38 (2004).

Merino, A. et al. Inferring changes in soil organic matter in post-wildfire soil burn severity levels in a temperate climate. Sci. Total Environ. 627, 622–632 (2018).

Jordanova, N., Jordanova, D. & Barrón, V. Wildfire severity: Environmental effects revealed by soil magnetic properties. Land Degrad. Dev. 30, 2226–2242 (2019).

Certini, G. Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia 143, 1–10 (2005).

Knicker, H. How does fire affect the nature and stability of soil organic nitrogen and carbon?. Rev. Biogeochem 85, 91–118 (2007).

Mataix-Solera, J., Cerdà, A., Arcenegui, V., Jordán, A. & Zavala, L. M. Fire effects on soil aggregation: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 109, 44–60 (2011).

Vacchiano, G. et al. Fire severity, residuals and soil legacies affect regeneration of Scots pine in the Southern Alps. Sci. Total Environ. 472, 778–788 (2014).

Ferreira, A. J. D. et al. Influence of burning intensity on water repellency and hydrological processes at forest and shrub sites in Portugal. Soil Res. 43, 327–336 (2005).

Lombao, A. et al. Effect of repeated soil heating at different temperatures on microbial activity in two burned soils. Sci. Total Environ. 799, 149440 (2021).

Girona-García, A., Ortiz-Perpiñá, O., Badía-Villas, D. & Martí-Dalmau, C. Effects of prescribed burning on soil organic C, aggregate stability and water repellency in a subalpine shrubland: Variations among sieve fractions and depths. Catena (Amst) 166, 68–77 (2018).

Bonanomi, G. et al. Impact of prescribed burning, mowing and abandonment on a Mediterranean grassland: A 5-year multi-kingdom comparison. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155442 (2022).

Plaza-Álvarez, P. A. et al. Changes in soil water repellency after prescribed burnings in three different Mediterranean forest ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 247–255 (2018).

Espinosa, J. et al. Fire-severity mitigation by prescribed burning assessed from fire-treatment encounters in maritime pine stands. Can. J. For. Res. 49, 205–211 (2019).

Sagra, J. et al. Prescribed fire effects on early recruitment of Mediterranean pine species depend on fire exposure and seed provenance. For. Ecol. Manage 441, 253–261 (2019).

Lindberg, H., Punttila, P. & Vanha-Majamaa, I. The challenge of combining variable retention and prescribed burning in Finland. Ecol. Process 9, 4 (2020).

Koivula, M. & Vanha-Majamaa, I. Experimental evidence on biodiversity impacts of variable retention forestry, prescribed burning, and deadwood manipulation in Fennoscandia. Ecol. Process 9, 11 (2020).

Fernandes, P. & Botelho, H. Analysis of the prescribed burning practice in the pine forest of northwestern Portugal. J. Environ. Manage 70, 15–26 (2004).

Alcañiz, M., Outeiro, L., Francos, M. & Úbeda, X. Effects of prescribed fires on soil properties: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 613, 944–957 (2018).

Hille, M. & Den Ouden, J. Improved recruitment and early growth of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) seedlings after fire and soil scarification. Eur. J. For. Res. 123, 213–218 (2004).

Prévosto, B., Bousquet-Mélou, A., Ripert, C. & Fernandez, C. Effects of different site preparation treatments on species diversity, composition, and plant traits in Pinus halepensis woodlands. Plant. Ecol. 212, 627–638 (2011).

Battipaglia, G. et al. The effects of prescribed burning on Pinus halepensis Mill. as revealed by dendrochronological and isotopic analyses. For. Ecol. Manage 334, 201–208 (2014).

Pausas, J. G. Evolutionary fire ecology: lessons learned from pines. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 318–324 (2015).

Fernandes, P. M., Vega, J. A., Jimenez, E. & Rigolot, E. Fire resistance of European pines. For. Ecol. Manage 256, 246–255 (2008).

Negri, S., Arcenegui, V., Mataix-Solera, J. & Bonifacio, E. Extreme water repellency and loss of aggregate stability in heat-affected soils around the globe: Driving factors and their relationships. Catena (Amst) 244, 108257 (2024).

Vieira, D. C. S. et al. Wildfires in Europe: Burned soils require attention. Environ. Res. 217, 114936 (2023).

Papierowska, E. et al. Compatibility of methods used for soil water repellency determination for organic and organo-mineral soils. Geoderma 314, 221–231 (2018).

Botelho, H. S., Vega, J. A., Fernandes, P. & Rego, F. M. C. Prescribed fire behavior and fuel consumption in Northern Portugal and Galiza Maritime Pine stands. Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. For. Fire Res. 1, 343–353 (1994).

Hood, S. M., Varner, J. M., Jain, T. B. & Kane, J. M. A framework for quantifying forest wildfire hazard and fuel treatment effectiveness from stands to landscapes. Fire Ecol. 18, 33 (2022).

Knicker, H. Pyrogenic organic matter in soil: Its origin and occurrence, its chemistry and survival in soil environments. Quatern. Int. 243, 251–263 (2011).

Almendros, G., Knicker, H. & González-Vila, F. J. Rearrangement of carbon and nitrogen forms in peat after progressive thermal oxidation as determined by solid-state 13C-and 15N-NMR spectroscopy. Org Geochem 34, 1559–1568 (2003).

Partelli-Feltrin, R. et al. Death from hunger or thirst? Phloem death, rather than xylem hydraulic failure, as a driver of fire-induced conifer mortality. New Phytol. 237, 1154–1163 (2023).

Reich, P. B., Abrams, M. D., Ellsworth, D. S., Kruger, E. L. & Tabone, T. J. Fire affects ecophysiology and community dynamics of central Wisconsin oak forest regeneration. Ecology 71, 2179–2190 (1990).

Schweingruber, F. H. Modification of the tree-ring structure due to extreme site conditions. Wood structure and environment 85–126 (2007).

Wallin, K. F., Kolb, T. E., Skov, K. R. & Wagner, M. R. Effects of crown scorch on ponderosa pine resistance to bark beetles in northern Arizona. Environ. Entomol. 32, 652–661 (2003).

González-Pérez, J. A., González-Vila, F. J., Almendros, G. & Knicker, H. The effect of fire on soil organic matter—a review. Environ. Int. 30, 855–870 (2004).

Capra, G. F. et al. The impact of wildland fires on calcareous Mediterranean pedosystems (Sardinia, Italy)–An integrated multiple approach. Sci. Total Environ. 624, 1152–1162 (2018).

Atanassova, I. & Doerr, S. H. Changes in soil organic compound composition associated with heat-induced increases in soil water repellency. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 62, 516–532 (2011).

Negri, S., Stanchi, S., Celi, L. & Bonifacio, E. Simulating wildfires with lab-heating experiments: Drivers and mechanisms of water repellency in alpine soils. Geoderma 402, 115357 (2021).

Agee, J. K. Fire and pine ecosystems. Ecology and biogeography of Pinus 193–218 (1998).

Bär, A. & Mayr, S. Bark insulation: ten central Alpine tree species compared. For. Ecol. Manage 474, 118361 (2020).

Espinosa, J., de Rivera, O. R., Madrigal, J., Guijarro, M. & Hernando, C. Predicting potential cambium damage and fire resistance in Pinus nigra Arn. ssp. salzmannii. For. Ecol. Manage 474, 118372 (2020).

Van Wagner, C. E. Height of crown scorch in forest fires. Can. J. For. Res. 3, 373–378 (1973).

Harrington, M. G. Predicting Pinus ponderosa mortality from dormant season and growing-season fire injury. Int. J. Wildland Fire 3, 65–72 (1993).

De Micco, V., Zalloni, E., Balzano, A. & Battipaglia, G. Fire influence on Pinus hale pensis: wood responses close and far from scar Wood structure in plant biology and ecology (Brill, 2013).

Sparks, A. M. et al. Impacts of fire radiative flux on mature Pinus ponderosa growth and vulnerability to secondary mortality agents. Int. J. Wildland Fire 26, 95–106 (2017).

Gaylord, M. L. et al. Drought predisposes piñon–juniper woodlands to insect attacks and mortality. New Phytol. 198, 567–578 (2013).

Martínez-Vilalta, J. et al. Hydraulic adjustment of Scots pine across Europe. New Phytol. 184, 353–364 (2009).

Tedersoo, L. et al. 2014 Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346, 1256688 (1979).

Strieder, E. & Vospernik, S. Intra-annual diameter growth variation of six common European tree species in pure and mixed stands. Silva Fennica https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.10449 (2021).

Zhao, M. & Running, S. W. Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009. Science 1979(329), 940–943 (2010).

Choler, P. Above-treeline ecosystems facing drought: lessons from the 2022 European summer heat wave. Biogeosciences 20, 4259–4272 (2023).

Santín, C., Doerr, S. H., Merino, A., Bryant, R. & Loader, N. J. Forest floor chemical transformations in a boreal forest fire and their correlations with temperature and heating duration. Geoderma 264, 71–80 (2016).

Caudullo, G., Welk, E. & San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. Chorological maps for the main European woody species. Data Brief 12, 662–666 (2017).

Eilmann, B., Zweifel, R., Buchmann, N., Fonti, P. & Rigling, A. Drought-induced adaptation of the xylem in Scots pine and pubescent oak. Tree Physiol. 29, 1011–1020 (2009).

Savi, T. et al. Drought-induced dieback of Pinus nigra: a tale of hydraulic failure and carbon starvation. Conserv. Physiol. 7, coz012 (2019).

Perruchoud, D., Walthert, L., Zimmermann, S. & Lüscher, P. Contemporary carbon stocks of mineral forest soils in the Swiss Alps. Biogeochemistry 50, 111–136 (2000).

Aragoneses, E., García, M., Salis, M., Ribeiro, L. M. & Chuvieco, E. Classification and mapping of European fuels using a hierarchical, multipurpose fuel classification system. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1287–1315 (2023).

Kong, J., Yang, J. & Cai, W. Topography controls post-fire changes in soil properties in a Chinese boreal forest. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 2662–2670 (2019).

Fréjaville, T. & Curt, T. Spatiotemporal patterns of changes in fire regime and climate: defining the pyroclimates of south-eastern France (Mediterranean Basin). Clim. Change 129, 239–251 (2015).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. (2006).

Servizio Geologico d’Italia. Carta geologica d’Italia 1:50000. Regione Piemonte, Direzione Regionale Servizi Tecnici e di Prevenzione. https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/temi/protezione-civile-difesa-suolo-opere-pubbliche/geologia-prevenzione-rischio-geologico/cartografia-geologica/progetto-carg-carta-geologica-ditalia-150000# (2009).

Adkins, J., Docherty, K. M., Gutknecht, J. L. M. & Miesel, J. R. How do soil microbial communities respond to fire in the intermediate term? Investigating direct and indirect effects associated with fire occurrence and burn severity. Sci. Total Environ. 745, 140957 (2020).

Matosziuk, L. M. et al. Short-term effects of recent fire on the production and translocation of pyrogenic carbon in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Front. For. Global Change 3, 6 (2020).

Ascoli, D. et al. Harmonized dataset of surface fuels under Alpine, temperate and Mediterranean conditions in Italy. A synthesis supporting fire management. iForest-Biogeosci. Forestry. 13, 513 (2020).

Pyne, S. J., Andrews, P. L., Laven, R. D. & Cheney, N. P. Introduction to wildland fire. Forestry 71, 82 (1998).

Alexander, M. E. Calculating and interpreting forest fire intensities. Can. J. Bot. 60, 349–357 (1982).

Rego, F. C. et al. Fuel and Fire Behavior Description Fire Science: From Chemistry to Landscape Management (Springer, 2021).

Reinhardt, E. D. & Dickinson, M. B. First-order fire effects models for land management: overview and issues. Fire Ecol. 6, 131–142 (2010).

Peterson, D. L. & Ryan, K. C. Modeling postfire conifer mortality for long-range planning. Environ. Manage 10, 797–808 (1986).

Melcher, P. J., Zwieniecki, M. A. & Holbrook, N. M. Vulnerability of xylem vessels to cavitation in sugar maple scaling from individual vessels to whole branches. Plant Physiol. 131, 1775–1780 (2003).

Gärtner, H. & Schweingruber, F. H. Microscopic preparation techniques for plant stem analysis. Tree-ring Res. 70, 55–56 (2013).

Gonzalez-Benecke, C. A., Martin, T. A. & Peter, G. F. Hydraulic architecture and tracheid allometry in mature Pinus palustris and Pinus elliottii trees. Tree Physiol. 30, 361–375 (2010).

Parsons, A., Robichaud, P. R., Lewis, S. A., Napper, C. & Clark, J. T. Field Guide for Mapping Post-Fire Soil Burn Severity (Citeseer, 2010).

Gee, G. W. Particle-size analysis. Methods Soil Analysis Part Phys. Methods. 5(255), 293 (2002).

Harris, D., Horwáth, W. R. & Van Kessel, C. Acid fumigation of soils to remove carbonates prior to total organic carbon or carbon-13 isotopic analysis. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 65, 1853–1856 (2001).

Uchimiya, M., Wartelle, L. H., Klasson, K. T., Fortier, C. A. & Lima, I. M. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on biochar property and function as a heavy metal sorbent in soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 2501–2510 (2011).

Rivas-Ubach, A. et al. Moving beyond the van Krevelen diagram: A new stoichiometric approach for compound classification in organisms. Anal. Chem. 90, 6152–6160 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Consorzio Forestale Alta Val Susa, the Corpo Volontari Antincendi Boschivi of the Piedmont Region, the Civil Protection of the Piedmont Region.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the PB-PINE project (Effetti a breve e lungo termine del fuoco prescritto sul sistema pianta – suolo in pinete alpine, funded by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Torino), the SOILFIRE project (Compagnia di San Paolo), the Agritech National Research Center and the European Union Next-Generation EU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) – MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4 – D.D. 1032 June 17, 2022, CN00000022), the European Union as part of the FIRE-ADAPT project, Grant Agreement N° 101086416.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: D.A., E.B., F.S., R.G., S.N., A.B.; Methodology: E.B., F.S., A.Cr., S.N., R.G., S.C.; Validation: A.Cr., A.P., F.S., E.B., D.A., S.C.; Formal analysis: R.G., S.N., S.C., A.Ch., L.C., M.U., F.S.; Investigation: R.G., S.N., A.B.; Data curation: R.G., S.N., A.B.; Writing – original draft: R.G., S.N., A.B.; Writing – review and editing: all the authors; Funding acquisition: F.S., D.A., E.B.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of compliance

The prescribed experiment was conducted in agreement with national regulations (Law 353/2000 as modified by Law 155/2021) and regional regulations (Regional Law 15/2018), and under the supervision of Consorzio Forestale Alta Val Susa, the Corpo Volontari Antincendi Boschivi of the Piedmont Region, and the Civil Protection of the Piedmont Region.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gamba, R., Negri, S., Bono, A. et al. Prescribed burning has negligible effects on the plant-soil system in Pinus sylvestris L. forests of the European Alps. Sci Rep 15, 12076 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97239-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97239-1