Abstract

Achieving a high energy density in liquid metal batteries (LMBs) still remains a big challenge. Due to the multitude of affecting parameters within the system, traditional ways may not fully capture the complexity of LMBs. The artificial intelligence approach can be effectively applied to deal with low energy density issues. Herein, we represented the first implementation of the Gaussian Process Regression to predict the LMBs’ energy density to attain the highest accuracy compared to existing models. Four different kernels, namely Exponential, Matern5/2, Rational Quadratic, and Squared Exponential were utilized to achieve the most accurate GPR model. A huge dataset containing 2158 LMB datapoint was gathered from the literature. It contains 41 input parameters, including alloy-related, LMB-related, and creative features. The GPR-Exponential model showed the greatest battery energy density estimate accuracy among the proposed models. The training and testing R2 values were 0.9976 and 0.9975, respectively, indicating the near-perfect accuracy which makes it the most precise model that has been presented so far. According to sensitivity analysis outcomes, it can be claimed that Sb mole fraction, average ionization energy, and average melting temperature with the respective relevancy factors of 0.6672, 0.6550, and 0.6507 could noticeably affect the LMBs’ energy density. Furthermore, the results showed that the LMBs’ energy density is more sensitive to the electrode-dependent and operational parameters rather than the electrolyte situation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reliance on fossil fuels has resulted in environmental and societal issues, including greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, and ozone layer depletion. This has driven interest in renewable energy sources, though their intermittent nature, particularly in solar and wind power, poses challenges to power grid stability1,2,3,4. Balancing power supply and load during peak hours is crucial5. Electrochemical energy storage, known for adaptability and high energy density, efficiency, and flexible sizing, offers advantages over other methods6,7,8,9. Batteries are promising energy storage systems and have evolved with diverse cathode, anode, and electrolyte combinations. Lithium is preferred for its high capacity (3860 mAh g⁻¹) and low redox potential (-3.04 V vs. SHE) but faces challenges such as dendritic growth, volumetric changes, and electrolyte decomposition during cycling. Recent research over the past decade has explored solutions, including liquid metal anodes2,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

A Liquid Metal Battery (LMB) consists of two electrodes in liquid metal form with a molten salt electrolyte9,19. Electrode materials are chosen for abundance and cost-effectiveness10,20,21, remaining liquid at operational temperatures and offering significant density differences22. The positive electrode comprises a heavier metal with high electronegativity (Bi, Pb, Hg, Sb, Sn, or Zn)10,19,20,23, while the negative electrode consists of a lighter metal with low electronegativity (Ca, Na, Li, Mg, or K)19,22. The difference in electronegativity and the electron-donating/accepting characteristics facilitate the alloying reaction between the electrodes. The alloying reaction is thermodynamically favorable but electrochemically regulated by the electrolyte. Liquid phases in LMBs enhance properties for rapid charging and discharging. They enable efficient performance with superior kinetic and transport properties. Density differences create distinct layers, eliminating the need for membranes or separators5,24,25 and benefitting higher current density, extended cycle life, simplified manufacturing processes, and more effortless scalability6,21. The absence of solid-state interfaces reduces dendrite formation risk. Liquid metals possess a high electroactive materials concentration inherently, offering the potential for high capacity and energy storage capabilities compared to conventional electrode materials. On the other hand, high operating temperatures, safety concerns, increased corrosion risks and speed, and sensitivity to motion, limiting mobile applications, are the major drawbacks26. Despite limitations, LMBs offer substantial advantages, making them compelling for research.

Since the invention of the first LMB, numerous researchers and industry entities have been attracted to this technology2,27. In 2018, an Sb-Bi-Sn positive electrode with a low melting point was utilized in an LMB by Zhao et al.28, achieving an energy density of around 260 Wh kg− 1 28. Yan et al.24 demonstrated a Li∥Sb LMB using a solid antimony cathode, a liquid lithium anode, and a LiF-LiCl-LiBr electrolyte. This setup showcased an energy density of 421.6 Wh kg− 1, comparable to the Li∥Te-Sn LMB (495.9 Wh kg− 1 ref.29), albeit at a lower cost24. Zhou et al.30 improved the actual energy density of a Li∥Sb-Sn LMB from 20 to 30 Wh kg− 1 to 135 Wh kg− 1 by increasing the areal capacity, reducing electrolyte weight, increasing the Sb content in the cathode, and optimizing the structural components. A dual-active Sb-Zn electrode was designed and utilized in a Li∥Sb-Zn LMB by Xie et al.31. The average discharge voltage and the energy density values achieved by this system were 0.763 V at 100 mA cm− 2 and 290.6 Wh kg− 1 respectively32 .Lately, exploring gallium-based LMBs has attracted a growing interest33. In their study, Wang et al.34, synthesized GaSn nanoparticles encapsulated by reduced graphene oxide (rGO) with exceptional structural integrity and electrochemical performance. This research could pave the way for room-temperature LMBs34.

While experimental research provides valuable insights, it is often expensive and time-consuming. Precise predictions of future battery capacity are crucial for effective management. To address this, various studies have developed predictive models. Xu et al.35 used a dual fuzzy-based adaptive extended Kalman filter to estimate the state of charge (SOC) in LMBs, achieving higher accuracy and robustness than conventional algorithms35. A multiphase numerical model was developed by Godinez-Brizuela et al.36 that simulates the charge and discharge process of an LMB battery. Volume change and species redistribution were identified as key factors in predicting the maximum theoretical capacity36. Despite numerous battery models in the literature6,37,38,39,40, there is growing interest in data-driven methods for their effectiveness in addressing non-linear problems, especially with large datasets5.

ML models have greatly advanced research in energy storage, but high-accuracy models for LMBs are still developing. In a study by Wang et al.41, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) with a squared exponential kernel function was utilized to estimate the SOC in an LMB. Experimental data validated their model, showing strong compatibility between the experimental and predicted results41. Shi et al.5 proposed a hybrid model combining empirical mode decomposition, GPR model, and a relevant vector machine to predict long-term capacity. An RMSE of 0.141 for a 50 Ah battery and 0.117 for a 20 Ah battery were achieved5. In a recent study, Zhou et al.9 used alloy-related and LMB-related features as input parameters for an experimentally validated ML technique to expedite the discovery of multi-element electrodes with optimal electrochemical properties for LMBs. Various ML techniques including linear regression, random forest, and XGBoost, were evaluated for predicting target parameters. XGBoost was the best algorithm for predicting energy density, achieving R2, MAE, and MRE values of 0.9715, 4.28, and 0.0704, respectively9.

While the developed numerical and battery models can be helpful, they may not fully capture the complexity of LMBs due to the multitude of parameters at play in the system. For example, the model developed by Godinez-Brizuela has overlooked certain transport mechanisms36. In light of this, ML methods offer an advantage by sidestepping the complex analysis and solving processes of battery system mechanisms5. Currently, there have been few ML studies conducted on LMBs, with most focusing on the capacity or SOC of these batteries. Given that low energy density is a major drawback for LMBs32, future experimental studies may prioritize addressing this challenge. A reliable and accurate model is needed to assist in experimental work. The inclusion of a kernel function, both predefined and custom kernels, enables the GPR algorithm to capture a wide variety of behaviors from the data42. The expressivity of this model, as a non-parametric model, makes it a reliable choice for dealing with complex systems such as LMBs43.

This research article represents the first investigation into predicting the energy density of liquid metal batteries using a GPR model to attain a near-perfect accuracy compared to existing models. The study incorporates 41 parameters as input variables for the GPR model and trains it using four different kernel functions; namely, exponential, matern5/2, rational quadratic, and squared exponential. The article extensively discusses machine learning methodology and data preprocessing techniques. The GPR model is validated by comparing its predictions with experimental data available from the relevant literature. Various statistical parameters, including R2, MRE, MSE, RMSE, and MAE, are calculated and evaluated to assess the model’s accuracy. A sensitivity analysis is also conducted to identify the most influential parameters affecting the energy density.

Methodology

Gaussian process regression (GPR)

A Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is a probabilistic, non-parametric, Bayesian approach for regression analysis44,45. When we choose two or more points in a function (i.e., different input-output pairs), observations of the outputs at these points follow a joint (multivariate) Gaussian distribution which is known as a Gaussian process. The more formal definition of a Gaussian process is a collection of random variables any finite number of which have a joint (multivariate) Gaussian distribution46,47. In GPR, we aim to model the relationship between input variables X and output variables Y as a distribution over functions. Given a set of observed data points (Xobs, Yobs), the goal is to estimate the output Ynew for new input data points Xnew. The mean function, \(\mu \left( X \right)\), and covariance function (kernel), \(k\left( {X,X^{\prime } } \right)\) completely characterize A Gaussian Process. For a set of input points X and output points Y, the Gaussian Process is defined as Eq. (1) 48.

where \(f\left( X \right)\) the latent function is the mean function and the covariance function.

It is assumed that the observed data is corrupted by Gaussian noise \(\varepsilon \sim N(0,\sigma _{\varepsilon }^{2})\); thus, the observed output can be written as Eq. (2).

For making predictions at new points Xnew, the predictive distribution is computed according to Eq. (3).

where the mean value, \({\mu _{new}}\), and the covariance \({\Sigma _{new}}\)are defined as Eqs. (4)-(5).

where Knew, obs is the covariance matrix between new inputs and observation inputs, Kobs is the covariance matrix between observations, Knew, new is the covariance matrix between new inputs, Knew, obs is the covariance matrix between new inputs and observation inputs, Kobs, new is the covariance matrix between the observation inputs and new inputs, and I is the identity matrix.

The selected kernel function can affect the final GPR model’s strength and prediction ability robustness, including a symmetric invertible matrix. The kernel functions are used to calculate the covariance matrices. In this regard, Schulz et al.49 provided further information about the formulation and utilization of the GPR model. As presented in Eqs. (6)–(9), four alternatives, including Exponential, Matern5/2, Rational quadratic, and Squared exponential, are employed to choose the proper kernel function.

where kE is the Exponential kernel function, kM is the Matern5/2 kernel function, kRQ is the Rational quadratic kernel function, kSE is the Squared exponential kernel function, \(\iota\) is the length scale,\({\sigma ^2}\)is the variance, a is the scale-mixture,\(\nu\) is the positive parameter,\({K_\nu }\) is the modified Bessel function, and \(\Gamma\) is the gamma function.

Data collection

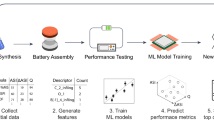

In this study, 2158 LMB datasets are gathered from the literature9. The employed dataset is provided in the supporting information. Different battery features and gravimetric energy densities are presented in the dataset. To predict the energy density of LMBs, 4 alloy-related features, 15 LMB-related features, and 22 creative features9 are considered as input parameters. Additionally, the related battery energy density is used as an output parameter. To achieve a model with high accuracy, 30% of the dataset is randomly selected as the test dataset, and the remaining 70% is employed to train the model. The considered procedure is presented in Fig. 1.

Model evaluations

where n is the total number of data points, and m is the mean value.

Besides the statistical parameters, the Relative Deviation of each data point can also be calculated by comparing the experimental and predicted values according to Eq. (15).

Model development

As mentioned before, 41 input variables, including 4 alloy-related features, 15 LMB-related features, and 22 creative features9, were used to predict the LMBs’ energy density as the target variable. In this study, the MATLAB R2022b package, commonly utilized in ML problems and soft modeling, implements the established GPR models. The hardware equipped with an Intel (R) Core (TM) i7-10510U CPU @ 1.80 GHz 2.30 GHz processor and 16.0 GB RAM was utilized in all simulations. The respective computational times were about 13.46, 6.5, 14.3, and 6.36 min for the GPR-Exponential, GPR-Matern5/2, GPR-Rational Quadratic, and GPR-Squared Exponential models. For each case, the model hyperparameters and respective kernel parameters were meticulously tuned and optimized to ensure optimal performance. The optimized parameters are presented in Table S1.

Results and discussion

Outlier analysis

Each dataset could conceivably contain some outlier data. For a variety of reasons including instrumental or human errors, degree of accuracy, and research assumptions, these data might constitute part of the dataset. The outlier data behaves differently from the other data points, which leads to inaccuracies in the ML algorithms. Thus, These data must be excluded as suspected data from the training and testing processes51. To determine the outlier data, several techniques have been proposed so far. The leverage method is one of the most well-known and frequently used techniques. The Hat matrix can be obtained using this method based on Eq. (16) 51.

where H is the Hat matrix, U is the (n ×p) matrix, n is the datapoint number, p is the number of model parameters, and t is the transpose matrix.

Equation (16) shows that the corresponding diagonal element in the Hat matrix equals the associated Hat value (HV) of each data point. The critical leverage limit in this method is ascertained based on Eq. (17) 51.

where H* is the critical leverage limit, n is the number of a datapoint, and p is the number of model parameters.

Utilizing Eqs. (16) and (17), the Hat values and crucial leverage limit are determined. William’s plot then graphically identifies the outlier or suspected data. The discrepancy between the empirical and associated predicted value is known as the residual value. Standardized residual values (R) are calculated by dividing residual values by their standard deviation. The standardized residual values (R) are provided against the Hat values in William’s plot. The data is in the range of -5 and 5 has an acceptable level of accuracy based on this plot. Data that comes outside of these constraints is considered to be an outlier or suspected data, and then subsequently removed from the procedures for training and testing. According to Fig. 2, it is clear that most of the data relevant to battery energy density are located within the acceptable range. For the GPR-Exponential, GPR-Matern5/2, GPR-Rational Quadratic, and GPR-Squared Exponential models, the discovered number of outlier data are 86, 87, 87, and 87, respectively. These represent 3.98%, 4.03%, 4.03%, and 4.03% of the total number of data. This indicates that the dataset collected from the literature can be efficiently employed to test and train the four ML models considered in this study.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is used to assess each input parameter’s impact on the variation of the output variable. This analysis calculates each input parameter’s relevancy factor (r) based on Eq. (18).

where \({X_{k,\,i}}\)is the ‘i’ th data of the ‘k’ th input variable, \({\bar {X}_k}\)is the ‘k’ th input data average of the ‘k’ th input variable, \({Y_i}\)is the ‘i’ th data of the output variable, \(\overline {Y}\)is the output data average of the output variable, and n is the number of the data points.

Equation (18) indicates that the relevancy factor is between − 1 and 1. When the relevancy factor is positive, the explored input parameter positively influences the output variable. If this factor is negative, the reverse occurs. As a result and regardless of its sign, the impact of the parameter on the output variable increases when the associated relevancy factor rises. By computing the relevancy factor for each parameter, the influence of the input variables on the amount of battery energy density is illustrated in Fig. 3. Considering the obtained outcomes, Sb mole fraction, average ionization energy, and average melting temperature have the most significant effect on the energy density of the LMBs. These features relevancy factors are 0.6672, 0.6550, and 0.6507, respectively.

On the other hand, λ (covalent), KI mole fraction, and cycles, with the respective relevancy factors of -0.0029, 0.0130, and − 0.0300, have the least effect. It is evident from Fig. 3 that 20 of the 41 input parameters have relevancy factors greater than 0.4. This demonstrates that LMB is a highly sensitive system, as even little alterations in its design parameters lead to noticeable variations in the system’s energy density. The theoretical capacity parameter has a relevancy factor of 0.5342. In terms of its relevancy factor magnitude, the theoretical capacity is the 12th affecting parameter on the LMB energy density. This shows that operational and non-theoretical parameters like cut-off voltage, anode mass, and area play more important roles in achieving the maximum energy density. Besides, it is also essential to establish a system with high theoretical capacity. As the current density with a respective relevance factor of -0.4688 increases, the system’s energy density decreases. In this regard, it can be claimed that all kinds of system overpotentials, such as electrolyte, cathodic, anodic, and ohmic overpotentials, are raised due to the increment of current density. Increasing the system’s overpotentials reduces voltage efficiency. Subsequently, energy efficiency and energy density will be decreased. The relevancy factor of area, anode mass, and cathode mass input parameters are 0.5900, 0.5346, and 0.4436, respectively. Therefore, it can be concluded that by scaling up the system, a higher energy density can be achieved, which is promising for developing large-scale applications of LMBs. The mole fraction of molten salt electrolyte components can also affect the energy density of LMBs. Based on the obtained results, increasing the LiF, KBr, and KI mole fractions with the respective relevancy factors of 0.3893, 0.2030, and 0.0130 has the greatest effect on improving the system’s energy density. On the other hand, as the LiBr, LiCl, and LiI mole fractions with the respective relevancy factors of -0.3832, -0.2610, and − 0.1274 increase, the energy density of LMB is reduced. Comparing these values, It can be claimed that the electrolyte-dependent parameters have relatively slight effect on the system’s energy density. Accordingly, the LMBs’ energy density is highly sensitive to the electrode-dependent parameters. Sb, Pb, Sn, and Bi mole fractions have relevancy factors of 0.6672, -0.5243, -0.3987, and − 0.0423, respectively. Thus, it can be said that increasing the Sb mole fraction along with decreasing the Pb, Sn, and Bi mole fractions improves the system’s energy density. Moreover, Sb, Pb, Sn, and Bi melting points are 631, 327, 232, and 272 °C, respectively, and their respective densities are 6697, 11340, 7265, and 9780 kg m-3 ref.52. It is evident that increasing the Sb mole fraction leads to rising average melting temperature and reducing average density. Thus, the system demonstrates the same behavior when the average melting temperature, average density, or component mole fractions are changed.

The results of Fig. 3 show that LMB is a highly sensitive system, and 20 of the 41 input parameters have relevancy factors greater than 0.4. These high-sensitive features and their respective relevancy factors are presented in Table S2. If there is a need to simplify the ML model and shorten the training and testing time, it can sometimes be done by training and testing the model using only features with high relevancy factors, at the cost of reduced model accuracy and higher error values. Analyzing the model using the high-sensitive features is also considered in the present research. The obtained results will be examined in the following sections.

Modeling results and validation

By calculating the statistical factors, the accuracy of established models can be evaluated. These factors are presented in Table 1. According to the given factors, it can be claimed that all four proposed models can be employed to estimate the energy density of LMBs. So that all employed models can fit the training and test dataset. The GPR-Exponential model has the greatest battery energy density estimate accuracy among the proposed models. For this model’s training data, the corresponding values of R2, MRE, MSE, RMSE, and MAE are 0.9976, 0.0084, 7.6985, 2.7746, and 1.1020. The test data can be utilized to evaluate the ability of these established models to predict the energy density of various LMBs. For the test data of the GPR-Exponential model, the statistical factors are 0.9975, 0.0044, 6.3021, 2.5104, and 0.6152, respectively. On the other hand, among the proposed models, the GPR-Squared Exponential has the lowest battery energy density estimation accuracy.

These results were expected considering the statistical properties of the dataset, Table S3. The statistical analysis reveals a high standard deviation, indicating significant fluctuations. This idea is further supported by the high coefficient of variation, which suggests considerable variability in the data. These findings highlight the presence of non-smooth behavior resulting from pronounced fluctuations. Additionally, the first-order difference between consecutive observations was computed. The relatively high standard deviation and maximum value, coupled with a very low minimum value of the first-order difference, suggest the occurrence of sharp jumps within the dataset. The smoothness of a kernel function is determined by the number of times it can be differentiated. As evident from Eq. (6) to (9), the Exponential kernel is differentiable only once, making it the least smooth but the most effective for this dataset. In contrast, the Squared Exponential kernel, which is infinitely differentiable and thus highly smooth, demonstrates the poorest performance53,54.

Linear Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost ML models were utilized in previous studies to predict the energy density of LMBs9. In Table 2, the accuracy of these models is compared with the GPR-Exponential as the most accurate model developed in the present study. The R2 values of the LR, RF, XGBoost, and GPR-Exponential models are 0.6662, 0.8636, 0.9715, and 0.9976, respectively. Accordingly, it can be claimed that the GPR-Exponential model proved to be more accurate compared to the other mentioned models. Additionally, the ability to use different kernel functions, which enables the model to capture various behaviors of the dataset, along with the availability of sufficient data points, makes the GPR model the best candidate for modeling a complex system such as LMBs. Therefore, the accuracy of previously reported models extends to a near-perfect value in the present research developing the GPR-Exponential model.

To simplify the GPR-Exponential model and shorten its computational time, the model hyperparameters and respective kernel parameters were meticulously tuned and optimized utilizing 20 high-sensitive features. The optimized parameters are presented in Table S4 and compared with the tuned parameters of the model which used all 41 input features. The accuracy of both developed models is also compared in Table S5 by calculating the statistical factors. The R2 values of total data are 0.9976 and 0.9848 for the GPR-Exponential (Features = 41) and GPR-Exponential (Features = 20), respectively. Besides, if just 20 high-sensitive input features are used, the computational time reduces from 13.34 to 6.5 min. So it can be claimed that using only features with high relevancy factors can simplify the GPR-Exponential model and shorten its training and testing time. On the other hand, the model accuracy is decreased and higher error values are attained.

In Fig. 4, the four suggested models’ accuracy is graphically assessed. As observed, The points indicating the actual values match the models-based predictive lines. This adjustment can be seen in all established training and test dataset models. The results presented in Fig. 4 confirm that the developed models can estimate the amount of energy density in various types of LMBs. Employing the proposed models might pave the way to achieving a desirable energy density for LMBs.

The accuracy of developed models may also be evaluated utilizing cross-plots. The bisector line in these plots illustrates the accuracy of the models. When the training and test data are closer to the bisector line, the developed model has more accuracy. The presented models’ cross plots are shown in Fig. 5. According to the outcomes, both training and test data are close to the bisector line in all four proposed models. Additionally, The linear fitting equations for both training and test data are provided in Fig. 5. These lines respective R2 values for the training data of the GPR-Exponential, GPR-Matern5/2, GPR-Rational Quadratic, and GPR-Squared Exponential models are 0.9976, 0.9952, 0.9965, and 0.9930. These values are 0.9975, 0.9958, 0.9969, and 0.9912 for the test data. Based on the calculation, it can be concluded that the energy density of LMBs can be properly estimated by employing the proposed models.

Figure 6 illustrates the actual battery energy density’s relative deviation and estimated values. The majority of the training and test data only show small relative deviations, further demonstrating the exceptional accuracy of the suggested models. The absolute mean values of relative deviation for the training data of the GPR-Exponential, GPR-Matern5/2, GPR-Rational Quadratic, and GPR-Squared Exponential models are 0.8390, 1.5379, 1.1183, and 2.0191, respectively. These values are 0.4412, 0.7135, 0.5896, and 1.1661 for the test data. It can be demonstrated that the GPR-Exponential has the greatest accuracy, and the GPR-Squared Exponential has the least accuracy among the established models. Additionally, all the developed models accurately predict the energy density of LMBs. To further examine the effect of using input features with high relevancy factors, the associated graphical assessment plot, cross plot, and relative deviation plot are also provided for the GPR-Exponential (Features = 20) model. The obtained results are also presented in Fig. S1.

Despite the sophistication of modern machine learning models, they remain subject to inherent biases and limitations. This study utilizes 41 input parameters for model training, selected based on existing literature. However, this selection may not fully capture all factors influencing energy density, potentially introducing bias if certain critical parameters are either overrepresented or omitted. Furthermore, while the dataset utilized in this study is sufficiently large to support generalization, there remains a possibility of inaccuracies when extrapolating to LMB systems that differ significantly from the training conditions. Additionally, the fundamental limitation of GPR models in handling large-scale datasets comprising thousands of observations should be considered.

Conclusion

This study explored the prediction of LMBs’ energy density by developing the GPR model with Exponential, Matern5/2, Rational Quadratic, and Squared Exponential kernel functions. 4 alloy-related features, 15 LMB-related features, and 22 creative features were considered as the input parameters. It can be concluded that all the employed models could accurately predict the associated energy density in the LMBs with the highest accuracy of the GPR-Exponential model. Namely, the statistical factors of R2, MRE, MSE, RMSE, and MAE for the test data of the mentioned model were 0.9975, 0.0044, 6.3021, 2.5104, and 0.6152, respectively. In contrast, the GPR-Squared Exponential model with the respective statistical factors of 0.9912, 0.0117, 22.6537, 4.7596, and 1.7815 had the lowest accuracy. The absolute mean value of relative deviation for the test data of the GPR-Exponential model was just 0.4412, indicating that the near-perfect model was achieved. The impact of all input features on the LMBs’ energy density was comprehensively examined by employing the sensitivity analysis. The Sb mole fraction, average ionization energy, and average melting temperature with the respective relevancy factors of 0.6672, 0.6550, and 0.6507 had the greatest effect on the battery energy density. The theoretical capacity parameter had a relevancy factor of 0.5342. This showed that operational and non-theoretical parameters like cut-off voltage, anode mass, and area play more important roles in achieving the maximum energy density. Besides, it is also essential to establish a system with high theoretical capacity. Moreover, It can be claimed that the electrolyte-dependent parameters had a relatively slight effect on the system’s energy density. Accordingly, the LMBs’ energy density is highly sensitive to the electrode-dependent parameters. The present research outcomes can pave the way to attaining an LMB with an optimal energy density.

Data availability

Data will be available upon the request of the corresponding author.

References

Nouri, F., Maghsoudy, S. & Habibzadeh, S. Dynamic insights of carbon management and performance enhancement approaches in biogas-fueled solid oxide fuel cells: A computational exploration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 50, 1314–1328 (2024).

Ding, Y., Guo, X. & Yu, G. Next-Generation liquid metal batteries based on the chemistry of fusible alloys. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1355–1366 (2020).

Goodenough, J. B. Electrochemical energy storage in a sustainable modern society. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 14–18 (2014).

Armand, M. & Tarascon, J. M. Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008).

Shi, Q. et al. The future capacity prediction using a hybrid data-driven approach and aging analysis of liquid metal batteries. J. Energy Storage. 67, 107637 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. State of charge Estimation for liquid metal battery based on an improved sliding mode observer. J. Energy Storage. 45, 103701 (2022).

Maghsoudy, S., Rahimi, M. & Dehkordi, A. M. Investigation on various types of ion-exchange membranes in vanadium redox flow batteries: experiment and modeling. J. Energy Storage. 54, 105347 (2022).

Maghsoudy, S., Rahimi, M., Molaei Dehkordi, A. & Fabrication Development, and simulation of vanadium redox flow battery for electrical energy storage. Nashrieh Shimi Va. Mohandesi Shimi Iran. 42, 387–404 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Accelerated design of electrodes for liquid metal battery by machine learning. Energy Storage Mater. 56, 205–217 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. Lithium–antimony–lead liquid metal battery for grid-level energy storage. Nature 514, 348–350 (2014).

Goodenough, J. B. & Kim, Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chem. Mater. 22, 587–603 (2010).

Seh, Z. W., Sun, J., Sun, Y. & Cui, Y. A highly reversible Room-Temperature sodium metal anode. ACS Cent. Sci. 1, 449–455 (2015).

Ding, Y., Zhang, C., Zhang, L., Zhou, Y. & Yu, G. Molecular engineering of organic electroactive materials for redox flow batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 69–103 (2018).

Ding, Y., Yu, G. A. & Bio-Inspired Heavy-Metal-Free, Dual-Electrolyte liquid battery towards sustainable energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 4772–4776 (2016).

Dai, G. et al. A Dual-Ion organic symmetric battery constructed from Phenazine-Based artificial bipolar molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9902–9906 (2019).

Liu, H. et al. Alloy anodes for rechargeable Alkali-Metal batteries: progress and challenge. ACS Mater. Lett. 1, 217–229 (2019).

Lin, D., Liu, Y. & Cui, Y. Reviving the lithium metal anode for high-energy batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 194–206 (2017).

Cheng, X. B., Zhang, R., Zhao, C. Z. & Zhang, Q. Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: A review. Chem. Rev. 117, 10403–10473 (2017).

Agarwal, D. et al. Recent advances in the modeling of fundamental processes in liquid metal batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112167 (2022).

Kim, H., Boysen, D. A., Ouchi, T. & Sadoway, D. R. Calcium–bismuth electrodes for large-scale energy storage (liquid metal batteries). J. Power Sources. 241, 239–248 (2013).

Bradwell, D. J., Kim, H., Sirk, A. H. C. & Sadoway, D. R. Magnesium–Antimony liquid metal battery for stationary energy storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1895–1897 (2012).

Duczek, C., Weber, N., Godinez-Brizuela, O. E. & Weier, T. Simulation of potential and species distribution in a Li||Bi liquid metal battery using coupled meshes. Electrochim. Acta. 437, 141413 (2023).

Dai, T. et al. Capacity extended bismuth-antimony cathode for high-performance liquid metal battery. J. Power Sources. 381, 38–45 (2018).

Yan, S. et al. Utilizing in situ alloying reaction to achieve the self-healing, high energy density and cost-effective Li||Sb liquid metal battery. J. Power Sources. 514, 230578 (2021).

Weber, N. et al. Cell voltage model for Li-Bi liquid metal batteries. Appl. Energy. 309, 118331 (2022).

Kim, H. et al. Liquid metal batteries: past, present, and future. Chem. Rev. 113, 2075–2099 (2013).

Ning, X. et al. Self-healing Li–Bi liquid metal battery for grid-scale energy storage. J. Power Sources. 275, 370–376 (2015).

Zhao, W. et al. High-Performance Antimony–Bismuth–Tin positive electrode for liquid metal battery. Chem. Mater. 30, 8739–8746 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Tellurium-tin based electrodes enabling liquid metal batteries for high specific energy storage applications. Energy Storage Mater. 14, 267–271 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Increasing the actual energy density of Sb-based liquid metal battery. J. Power Sources 534, (2022).

Xie, H. et al. A novel Sb-Zn electrode with ingenious discharge mechanism towards high-energy-density and kinetically accelerated liquid metal battery. Energy Storage Mater. 54, 20–29 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. A novel array current collector design enabling high energy efficiency liquid metal batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 487, (2024).

Xie, H. et al. High-performance bismuth-gallium positive electrode for liquid metal battery. J. Power Sources. 472, 228634 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Core-shell GaSn@rGO nanoparticles as high-performance cathodes for room-temperature liquid metal batteries. Scr. Mater. 217, 114792 (2022).

Xu, C., Zhang, E., Jiang, K. & Wang, K. Dual fuzzy-based adaptive extended Kalman filter for state of charge Estimation of liquid metal battery. Appl. Energy 327, (2022).

Godinez-Brizuela, O. E. et al. A continuous multiphase model for liquid metal batteries. J. Energy Storage 73, (2023).

Yang, G., Li, J., Fu, Z. & Guo, L. Adaptive state of charge Estimation of Lithium-ion battery based on battery capacity degradation model. Energy Procedia. 152, 514–519 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Aging modes analysis and physical parameter identification based on a simplified electrochemical model for lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage. 31, 101538 (2020).

Li, X., Wang, Z. & Zhang, L. Co-estimation of capacity and state-of-charge for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Energy 174, 33–44 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Electrochemical model-based state Estimation for lithium-ion batteries with adaptive unscented Kalman filter. J. Power Sources. 476, 228534 (2020).

Wang, S., Li, Z., Zhang, E., Zhou, M. & Wang, K. State of Charge Estimation for Liquid Metal Batteries with Gaussian Process Regression Framework. in International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC-Himeji 2022- ECCE Asia) 1665–1669 (2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.23919/IPEC-Himeji2022-ECCE53331.2022.9807007

Wu, R. & Wang, B. Gaussian process regression method for forecasting of mortality rates. Neurocomputing 316, 232–239 (2018).

Richardson, R. R., Osborne, M. A. & Howey, D. A. Gaussian process regression for forecasting battery state of health. J. Power Sources. 357, 209–219 (2017).

Gheytanzadeh, M. et al. An insight into Tetracycline photocatalytic degradation by MOFs using the artificial intelligence technique. Sci. Rep. 12, 6615 (2022).

Hoang, N. D., Pham, A. D., Nguyen, Q. L. & Pham, Q. N. Estimating Compressive Strength of High Performance Concrete with Gaussian Process Regression Model. Advances in Civil Engineering 2861380 (2016). (2016).

Gheytanzadeh, M. et al. Towards Estimation of CO2 adsorption on highly porous MOF-based adsorbents using Gaussian process regression approach. Sci. Rep. 11, 15710 (2021).

Gheytanzadeh, M. et al. Estimating hydrogen absorption energy on different metal hydrides using Gaussian process regression approach. Sci. Rep. 12, 21902 (2022).

Fu, Q. et al. Prediction of the diet nutrients digestibility of dairy cows using Gaussian process regression. Inform. Process. Agric. 6, 396–406 (2019).

Schulz, E., Speekenbrink, M. & Krause, A. A tutorial on Gaussian process regression: modelling, exploring, and exploiting functions. J. Math. Psychol. 85, 1–16 (2018).

Maghsoudy, S., Zakerabbasi, P., Baghban, A., Esmaeili, A. & Habibzadeh, S. Connectionist technique estimates of hydrogen storage capacity on metal hydrides using hybrid GAPSO-LSSVM approach. Sci. Rep. 14, 1503 (2024).

Hosseinzadeh, M. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Toward a predictive model for estimating viscosity of ternary mixtures containing ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 200, 340–348 (2014).

Perry, J. H. Chemical Engineers’ Handbook. (1950).

Rasmussen, C. E., Williams, C. K. & I. Gaussian processes for machine learning. (The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3206.001.0001 (2005).

Stein, M. L. Interpolation of Spatial Data: some Theory for Kriging (Springer New York, 1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1494-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors collaborated in writing, software development, conception, data gathering, and resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zakerabbasi, P., Maghsoudy, S., Baghban, A. et al. Artificial intelligence approach for estimating energy density of liquid metal batteries. Sci Rep 15, 12677 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97287-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97287-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Aligned electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibers coated with Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolytes for mechanically robust and flame-retardant membranes

Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society (2025)

-

Bridging classical and intelligent models: machine learning-guided adsorption isotherms for tailored acetone capture on porous carbon

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2025)