Abstract

Livestock-derived animal source foods (ASF) provide macro and micronutrients required for child growth and development, yet are under-consumed in many parts of the world where undernutrition persists. Using a modified conceptual framework of the social determinants of health, this study investigates the interrelationship between livestock ownership, ASF consumption, and child undernutrition (wasting, stunting, and underweight) in Rwanda. Using Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 3438 children aged 6–59 months and employing a multilevel mixed effects model, we investigate these interrelationships nationally, then focus on the Eastern Province and Nyagatare district, an area of high livestock production. Findings reveal that livestock ownership is significantly negatively associated with stunting (\(-0.056, p=0.048\)) and underweight \((-0.047, p=0.003\)); no significant association was found with wasting. No direct relationship between ASF consumption and child undernutrition was identified at the national level, though children who consumed ASF and lived in households with livestock were 6% (\(-0.063, p=0.048\)) less likely to be stunted and 3.6% (\(-0.036, p=0.047)\) less likely to be underweight. The effect of livestock ownership was particularly pronounced in Nyagatare district, where children in households with livestock were 35% (\(-0.355, p=0.032\)) less likely to be stunted than children in households without livestock. The study also found important associations with other social determinants of health, including maternal education and economic status, among others. Findings underscore the important role of livestock ownership in Rwanda and the need for a multi-disciplinary approach in leveraging increased ASF consumption to improve child nutrition outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutrition plays a key role in child growth and development, and global efforts have consequently focused on improving indicators of child undernutrition. Despite these efforts, high rates of child malnutrition persist, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Animal source foods (ASF) have been heralded as an effective tool for reducing malnutrition, particularly in children; however, ASF are expensive to purchase1, and keeping livestock for consumption of one’s own ASF comes with risks as well as benefits2. Following the UNICEF framework for child nutrition, a child’s nutritional status is largely determined by factors that are embedded in society, including religion, gender norms, educational status of the mother, and myriad others factors that determine diet and disease in that child. Rwanda is a LMIC who has made substantial strides in improving its development indicators, including under five mortality3; however, malnutrition is a persistent problem and, consequently, a high priority for the government. Using data from the 2019–2020 Demographic and Health Survey in Rwanda and a modified framework for social determinants of health, this study aims to explore and describe the predictors of child nutritional status with a focus on understanding the livestock ownership—ASF consumption—undernutrition nexus.

Background

In 2020, an astounding 148 million children under five (CU5) were estimated to be stunted (short for their age), while 45 million were estimated to experience wasting (low weight relative to height)4; fully 91% of stunted CU5 are living in LMICs5. Poor nutrition in early-life is also associated with a wide range of negative developmental outcomes, including reduced cognitive function, language acquisition, sensory-motor skills, overall mental development, academic achievement, and future intellectual potential6, all of which are impediments to various forms of productivity and progress. Chronic malnutrition during early childhood is estimated to contribute to 45% of deaths in CU57 but also a substantial economic burden in LMICs, reinforcing cycles of poverty8.

Similar to other health outcomes, factors influencing child nutritional status are embedded in multifactorial and complex systems, which can be understood through social determinants of health. These determinants include income, employment, housing and various other social factors, that interact to shape the conditions in which people live9. These factors interact to affect both the immediate (diet and disease) and underlying (food security, care behaviors, and health system and the environment) determinants of child nutrition10. Lack of access to nutrient-dense foods constrains diet quality, particularly of young children, with important short and long term health consequences. Animal source foods (ASF) are a rich source of nutrient-dense foods but are often missing in the diets of about 800 million people worldwide11. Increased consumption of ASF in LMICs has the potential to address the nutrient inadequacies common in predominantly starch-based diets12.Numerous studies have consistently shown a positive link between increased ASF consumption and improved child growth, cognitive function, and immune response13, though ASF consumption varies across regions, cultures, and households. In some regions, ASF consumption patterns are based on location and seasonality of available ASF14; while in other cultures, perceptions and beliefs regarding certain foods affect the frequency of ASF consumption15,16. Several studies have shown that varying religious and cultural norms, including intrahousehold food allocation practices, have impacted ASF consumption and its link to child nutrition17.

In LMICs where livestock serves as a major source of livelihood, ownership of livestock becomes a crucial factor shaping child nutritional outcomes. Livestock ownership can directly affect child nutrition through increased ASF availability and consumption18,19. Cows provide milk, beef, and dairy products, while chickens offer eggs and meat, and sometimes, depending on the region, they are a source of income20. Milk or meat consumption is generally positively associated with livestock-ownership21, and ASF consumption has been found to improve child nutrition status22. Livestock species that contributes most to ASF consumption vary substantially across regions and cultures23,24. ASF consumption offers sufficient nutritional content even when consumed in small volumes, warranting more benefits for children who have limited gastric capacities12,25.

Raising animals provides families with various other pathways for better health26. Livestock production serves as an important income-generating activity in many resource-limited settings, potentially enhancing child nutrition, by improving access to healthcare, education, sanitation, and other nutritious food27. Research suggests that owning livestock in Africa has been linked to a rise in consuming nutritious animal products, potentially improving nutritional outcomes26. A conceptual framework demonstrating typical social determinants of health with livestock ownership and ASF consumption embedded is represented in Fig. 1.

Despite the conceptual benefits and supporting evidence, however, the relationship between livestock ownership and nutritional outcomes is hardly understood. Human-livestock interactions are complex and may pose health risks as well as benefits, due to increased exposure to pathogens that can cause clinical diseases27. Livestock ownership has been shown to play a dual role, serving both as a protective factor against chronic malnutrition and a risk factor for mortality28,29.

Rwanda is a small land-locked country located in East Africa. Despite recent strides in improving various development indicators30, malnutrition remains a major concern (33% stunting rate). The Rwandan government has recognized and sought to harness the potential benefits of increasing ASF access to improve nutritional outcomes, having implemented initiatives such as the “One Cow per Poor Family” program31 and the “One Egg a Day” program for children32. However, translating policy into practice requires navigating a complex landscape of challenges. Factors such as poverty, limited land resources, and the threat of disease outbreaks can notably hinder livestock ownership and ultimately, constrain ASF availability for Rwandan households33. Thus, this study aims to understand the predictors of child nutritional status by unraveling the livestock ownership-ASF consumption-undernutrition nexus in Rwanda, using a modified framework of the social determinants of health. Within Rwanda, this study will compare and focus on child growth outcomes in Nyagatare district, which has among the highest livestock densities and dairy production of all districts34. High rates of malnutrition, combined with the government’s emphasis on the benefits of ASF consumption, makes Rwanda and ideal case study for this research.

Materials and methods

Data source and setting

This paper utilizes data from the 2019–20 Rwandan DHS, covering all Rwanda provinces and districts35. The Rwandan DHS, conducted every five years, is a cross-sectional survey implemented by the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) in collaboration with Ministry of Health (MoH). The data were collected from a nationally representative sample of 12,949 households in a way that allows national and regional level estimates of indicators. This study uses data from the child file, focusing on children aged 6–59 months. Because we are focused on ASF consumption, children under six months of age, who should by WHO recommendations receive only breastmilk, are not included in our sample. The final sample included 3,438 children selected to investigate dietary practices. Children who were not assessed for Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) per DHS guidelines—thus no data on ASF consumption—or with missing values in the outcome variables (child wasting, stunting, and underweight) were excluded from the analysis.

Variables

The primary outcome of this paper is child growth outcomes, which are assessed and used as standard measures of malnutrition: stunting, wasting, and underweight. The empirical analysis of child these outcomes uses standardized anthropometric indicators: Z-scores for height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ), and weight-for-height (WHZ), all calculated according to the 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards. Children were classified as stunted, underweight, or wasted if their HAZ, WAZ, or WAZ z-scores, respectively, fell below -2. Consequently, primary outcomes are binary, coded as “1” for malnourished and “0” otherwise.

The key explanatory variables in the study are livestock ownership and ASF consumption. Livestock ownership is coded as a dichotomous indicator, with “1” representing a household that reports owning any type of livestock, herds, or farm animals. We also assessed the intensity of livestock ownership by calculating the Tropical Livestock Unit (TLU) using the number and type of livestock. The measurement of TLU generates an index for livestock ownership by assigning higher weights by size of the livestock (0.8 for horses, 0.5 for cattle, 0.2 for pigs, 0.1 for small ruminants, 0.02 for rabbits and 0.01 for chickens). These weights are further multiplied by the number of each type of livestock.

ASF consumption was measured using a 24-h recall for each type of ASF (eggs, fish, meat, flesh, milk, or dairy). First, ASF consumption in children is measured as binary and coded as “1” if any of the ASF food groups are reportedly consumed by the child; otherwise, “0”. Furthermore, to analyze the impact of different types of ASF on child growth, we analyzed each type of ASF individually. This disaggregation was conducted in order to understand whether the consumption of different ASF types have varied effects on child nutrition36. For example, dairy is considered separately from meat, due to its high-quality protein content, typical lower cost, and reduced sensitivity to economic insecurity37. The disaggregation of ASF by type is also crucial, as different types of ASF offer different nutritional values, particularly for iron, vitamin A, and iodine, which are among the most deficient nutrients globally2. Additionally, milk was separated from dairy products due to its high prevalence and consumption in Nyagatare district compared to other regions of Rwanda.

Other socio-demographic covariates were selected based on the existing literature, following social determinants of health framework, and availability of those indictors in DHS dataset. These include various individual, maternal, household and community-level characteristics known to influence child nutritional status. Individual factors include birth order and child’s birth size, and maternal factors include mother’s age and education level. At the household level, the study controls for type of cooking fuel, number of antenatal care (ANC) visits, ownership of agricultural land, income level (using wealth index), and health insurance coverage. Community-level factors include place of residence (rural/urban).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the relationship between child nutritional status, livestock ownership and ASF consumption, we use separate regression models for stunting, wasting and underweight. Due to the hierarchical nature of the DHS data, where child characteristics are nested in the community, multilevel mixed-effect linear regression models were employed. Because the children are nested within rural–urban areas and these regions are nested within the districts, we fit a three-level mixed model with random intercepts at both rural/urban and district levels. The three-level mixed model can be specified as:

For \(i=1, \dots .., {n}_{jk}\) first level (child) observations nested within \(j=1, \dots .., {M}_{k}\) second-level groups (rural/urban), which are nested within \(k=1, \dots .., M\) third-level groups (district level). \(ChildNutrition\) refers to the different measurement of child growth outcomes of stunting, wasting and underweight; \(livestock\) and \(ASFConsumption\) refer to the livestock ownership and ASF consumption, respectively; and \(X\) refers to the vector of other covariates, e.g. sociodemographic factors that are used in the model. All the explanatory variables and error term in multilevel mixed effect models will have a row dimension \({n}_{jk}. {Z}_{jk}^{(3)}{u}_{jk}^{(3)}+{Z}_{jk}^{(2)}{u}_{jk}^{\left(2\right)}\) are the random effects associated with the district level and rural/urban level variations. The terms \({u}_{jk}^{(3)}\) and \({u}_{jk}^{\left(2\right)}\) represent the random intercept at the district and rural/urban levels. The numbers in superscripts (3 and 2) refer to the design matrix and random effects at third and second levels respectively. Before, including these covariates into the regression models, a bi-variate analysis was done to determine the significance. Some of the covariates such as mother’s Body Mass Index (BMI), anemia status, mother’s smoking behaviour, ANC visits, health insurance, agricultural land ownership, child sleeping under the mosquito nets, improved water and sanitation facilities were tested but dropped from the final model due to their insignificant association. The frequencies of all the variables considered in regression model are reported in Table 1.

For total sample in Rwanda and Eastern province, a three-level (individual, rural/urban, and district level) mixed effect linear regression was used to estimate the effect of livestock ownership and ASF consumption on child growth outcomes along with the other covariates. The models at the district level (Nyagatare) were only adjusted for two levels, individual and rural/urban clustering.

The fixed effects were used to estimate the association between child nutrition status, livestock ownership, ASF consumption and other covariates at individual, maternal household, and community level factors.

Furthermore, interaction terms between livestock ownership and ASF consumption were used to disentangle the independent effects of livestock ownership and ASF consumption and to better understand their combined effect as well. For example, livestock ownership may lead to greater ability to consume specific types of ASF, such as dairy products while also potentially limiting access to other types, like meat.We also interacted livestock ownership with different types of ASF when conducting heterogenous analysis to uncover how various ASF interact differently with livestock ownership. For example, children from households with access to dairy-producing animals can have different nutritional outcomes that those with primarily meat-producing livestock. By analyzing these interactions, we explore whether the relationship between livestock ownership and nutritional outcomes is specific to certain ASF types or whether broader patterns emerge across all ASFs.

Results

Descriptive statistics

A total weighted sample of 3,438 children, between 6–59 months old were included in the study. Table 1 represents the descriptive statistics of all the variables included in the analysis separately for Rwanda, Eastern province, and Nyagatare district. In Rwanda, the prevalence of childhood malnutrition is high with stunting rate at 35.1%; slightly lower rates are observed in Eastern Province 31.4% and in Nyagatare district 32.4%. Wasting is less prevalent in the country (Rwanda: 1.1%; Eastern province: 0.97%; Nyagatare: 0%). The prevalence of underweight is around 7.8% in Rwanda, 7.7% in Eastern province, and considerably less in Nyagatare (3.5%) as compared to the province and national average. These numbers are slightly different than Rwanda DHS report (2020) as our sample consists of children aged 6–59 months as opposed to 0–59 months used in the country report.

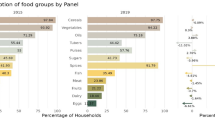

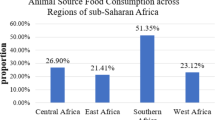

As expected, ASF consumption is high in Nyagatare district (50%) compared to province and national average (Eastern province: 44.1%; Rwanda: 39.5%). The difference is primarily due to milk consumption in the district: in Nyagatare, 45.6% of children were reported to be fed milk, compared to 34% in Eastern province and 26% in Rwanda overall. Conversely, consumption of all other ASF type is lower in Nyagatare compared to Eastern province and Rwanda overall. In examinging ASF consumption patterns by type, it is also noticeable that fish is the second most common ASF in Rwanda, where 14% of the household report feeding their children fish (Eastern province: 15.7%; Nyagatare: 8.8%).

Around 46.4% of the households in our sample reported owning livestock, herd, or farm animals. Livestock ownership is more common in Nyagatare district (51%) compared to the Eastern province (47.9%) and Rwanda. The average tropical livestock unit (TLU) was around 2 in Rwanda overall as well as Eastern province and in Nyagatare district. However, the relationship with intensity of the livestock (TLU) was not found to be significant.

Regarding other covariates, 17.3% of children are reported as small at birth in Rwanda, compared to 16.4% in Eastern Province and 12.1% in Nyagatare. Additionally, more than two thirds of mothers have primary education in Rwanda (65.5%). This percentage is even higher in Eastern Province (68.2%) and Nyagatare district (73.8%).Around 80% of the households has health insurance coverage in Rwanda (79.6% in Rwanda; 77% in Eastern province and Nyagatare district). Around 50% of the women visited for their ANC visits 1–3 times. Categorical variables for elevation levels were also included in the model. Most of the households were reported to be residing between 1000–2500 m of elevation. Table 1 also shows that most of the population in our sample resides in the rural area (around 80%).

Prevalence of child malnutrition in Rwanda across districts

Figures 2, 3, 4 demonstrate the spatial distribution of child growth outcomes in children aged 6–59 months in Rwanda across districts. In 2019/20, districts in the Northern and Western Provinces had the highest stunting rates (over 40%), while wasting was found to be most prevalent in some districts in the Southern Province (Nyaruguru and Gisagara districts). Prevalence of underweight was highest in the southern province and some of the eastern province districts (Kayonza) and northern province (Burera).

Child nutritional status, livestock ownership and ASF consumption

Table 2 presents regression results from the multilevel mixed effect regression model as specified in Eq. 1 above separately for stunting, wasting, and underweight.

Results reveal an overall negative and significant association between livestock ownership and stunting (Table 2). Livestock ownership reduced the probability of stunting by approximately 5%. For ASF consumption, there was no significant association found with stunting directly, but children who were fed ASF in households who reported livestock ownership were 6.3% lower probability of being stunted. Similar to stunting, livestock ownership was found to be significantly negatively associated with underweight; the probability of being underweight was 4.7% less among the children who belonged to households with livestock. Also, the probability of underweight reduced among the children who were fed ASF and belonged to the household with livestock, with negative and significant coefficient of the interaction term. In contrast to stunting and underweight, wasting was not found to be significantly associated with livestock ownership and ASF consumption at a country level.

For other confounders, a child’s size at birth was found to be significantly associated with the probability of stunting and underweight, with average and larger than average children at birth less likely to be stunted or underweight than children born small. No statistically significant association was found for child size at birth and wasting. Birth order (more than 4) was found to be a significant risk factor for stunting and underweight compared to the first-born children. No significant association was found between birth order wasting. Mother’s education level was also found to be a significant protective factor against stunting: children born to mothers with higher education were 14–15% less likely to be stunted than children born to mothers with no education. Mother’s education was not found to be associated with wasting and underweight in Rwanda. Interestingly, and aligning with previous literature, higher elevation was found to be a risk factor for stunting among CU5. The risk of stunting linearly increases with the higher altitude. Altitude was not found to be a significant factor for wasting or underweight. The wealth index upheld the expected sign and coefficient: children living in richer households are less likely to be stunted and underweight compared to those in poorer households.

Heterogeneous effects by types of ASF

Furthermore, in Table 3 we test the relationship between livestock ownership and children nutritional status, after controlling for different types of ASF. Ownership of livestock remains a significant factor in reducing the probability of stunting and underweight in Rwanda. However, no specific ASF, individually was found to be significantly associated with stunting except meat (col. 7). Consumption of meat was found to be significantly positively associated with the risk of stunting among children. One of the reason could be very few households eating meat in Rwanda overall (3.3%).

For wasting, livestock ownership was not found to be significantly associated. Milk consumption was found to be a risk factor for wasting among children with significant positive association. Further, consumption of milk and eggs among households with livestock was found to be positively associated with likelihood of wasting, with significant and positive interaction effects. The significant interaction effect of egg among livestock owning households needed further exploration as exposure to chickens (particularly chicken feces) are major sources of enteric disease38 and an important contributor to the under development of children under five39. To investiage this further, we tested specifically for chicken ownership in the household and its interaction with egg consumption (Table 4). Findings interestily reveal the effects of chicken ownership and its interation with egg consumption. While owning any type of livestock was not related with wasting as stated before, chicken ownership was positively and significantly related with wasting in Rwanda. Also the interaction effect of chicken with egg consumption appeared stronger than Table 3. Children who were fed egg in the households with chicken were 4.8% more likely to be wasted than children who were not fed eggs and belonged to household with no chickens.

For underweight, similar to stunting, livestock ownership was found to be negatively and significantly associated with likelihood of underweight (approximately 4% less likely). Among different type of ASF, none were found to be associated with underweight individually. Also, no interaction effects between livestock ownership and ASF consumption was noted for underweight in Rwanda.

Child nutritional status, livestock ownership, and ASF consumption in Eastern province and Nyagatare district

Table 5 presents region specific results for Eastern province and then Nyagatare district using the same model specification as in Eq. 1. All regression models include controls as specified in Table 2 but have not been presented here for the sake of brevity. As opposed to the country overall, at province level, we did not observe a significant effect of livestock ownership or ASF consumption on stunting. However, in Eastern province, significant and protective effect of livestock ownership was found on underweight and wasting.

In Nyagatare district, livestock ownership is found to be significantly and more strongly negatively associated with probability of stunting in the district (35.5%). No significant effect of ASF consumption was found on stunting. Additionally, no significant association was found between livestock ownership and underweight or ASF consumption and underweight in Nyagatare district. Wasting results for Nyagatare district are not reported as there were no cases of wasting in the district in 2019–20 in the DHS dataset.

Table 6 and 7 report results by ASF type for Eastern province and Nyagatare district. Milk consumption was found to be negatively associated with wasting in Eastern province. Children who consumed milk were 2% less likely to be wasted than children who did not consume milk in the region. Though, no other ASF type was found to be significantly associated individually. But the interaction of egg consumption with livestock ownership was found to be positively and significantly associated with wasting and underweight in Eastern province.

As stated before for Rwanda, after including chicken ownership in the households, though no significant effect of chicken ownership itself was found, the interaction effect of egg consumption and chicken ownership became stronger with higher probability of wasting by 10.9% and underweight by 18% among children.

In Nyagatare (Table 7), effect of livestock ownership on stunting was found to be strong and ranged from 25%-39%. Consumption of no individual ASF type was associated with child growth outcomes evaluated. Consumption of fish among households with livestock appeared to be risk factor for underweight in Nyagatare district.

Comparison across livestock-heavy districts

While Nyagatare district is the primary focus of this study, we conducted additional analyses to compare it with other livestock-heavy districts from different provinces in Rwanda (Northern, Southern, and Western). The top districts from each region were selected based on the average values of Tropical Livestock Units (TLU), resulting in the identification of Gakenge (Northern), Muhanga (Southern), and Karongi (Western). Regression analyses were performed for these districts, and the results are presented in Table 8.

In Gakenge, similar to Nyagatare, a significant and strong protective effect of livestock ownership on child nutritional status was observed, particularly with regard to stunting and underweight. Children from livestock-owning households in Gakenge were 75% less likely to be stunted and 24% less likely to be underweight. Moreover, the interaction between livestock ownership and ASF consumption was found to be negative and significant for both stunting and underweight, suggesting a compounded protective effect.

In contrast, no such protective effect was noted in other provinces. In Muhanga and Karongi, ASF consumption appeared to be a risk factor for stunting and underweight, respectively. Specifically, ASF consumption was associated with higher rates of stunting in Muhanga and higher rates of underweight in Karongi, highlighting the variability of the relationship between ASF consumption and child nutrition across districts.

Discussion

This study investigates associations between livestock ownership at the household level, ASF consumption, and child nutrition status in Rwanda, with a particular focus on Eastern province and Nyagatare district. Our findings reveal complex relationships that vary across child growth outcomes, geographic regions, livestock and ASF type, providing valuable insights into the potential role of livestock in addressing child malnutrition in Rwanda.

In most of the models, the relationship between livestock ownership and child nutritional status (stunting and underweight) demonstrated a trend towards a protective association. Our results align with and extend previous studies that have demonstrated positive associations between livestock ownership and improved child nutritional outcomes in LMICs (Azzarri et al., 2014; Hetherington et al., 2017). For instance, Azzarri et al. (2014) found similar positive effects of livestock ownership on child nutritional status in rural Uganda. These results echo the findings of Mosites et al. (2015) who found household livestock ownership to be associated with lower stunting prevalence in Ethiopia and Uganda. In LMICs, livestock ownership serves as a primary pathway to obtaining ASF, potentially explaining the significance of the interaction found. Livestock, such as cows, goats, sheep, and poultry, provide a readily available source of these vital nutrients for household consumption (Azzarri et al., 2014; Hetherington et al., 2017). However, our study provides more nuanced insights by examining these relationships in similar setting across different regions within Rwanda and considering multiple nutritional indicators. Unlike some previous studies that found uniform benefits of livestock ownership, our research highlights important regional variations, particularly the stronger protective effect in Nyagatare. This underscores the importance of context-specific analyses in understanding the livestock-nutrition nexus.

Child health outcomes are contingent on a delicate balance of proper diet, sanitation, and overall health. Livestock can positively influence both macro and micronutrient deficiencies through production and provision of ASF. In this paper, 24-h recall of ASF was not consistently associated with improved child nutritional outcomes, and its effect varied by type of ASF consumed and geography. Similar to Dumas et al. (2018) in Zambia, we did not find an effect of any type of ASF consumption on stunting, wasting, or underweight for Rwanda overall. At the national level, variation in ASF consumption across different population subgroup (including the households with and without livestocks) may cancel out any direct association with undernutrition. However, its interaction with livestock ownership was negative and significant, indicating protective effect of ASF consumption among household who owned livestock. This finding has important implications on the role of livestock production, above and beyond the production of ASF or income to purchase ASF. This signficies the importance of availability of ASF at home which facilitates ASF consumption in line with previous research in Rwanda highlighting affordability and low homestead production to be a major hindrance in ASF consumption42.

Though, the effect of livestock ownership also differ by type of livestock. It was noted that chicken ownership (exposure to which can results in zoonotic infections) was a significant risk factor for wasting and underweight in Rwanda. For different ASF types, we found milk consumption to be associated with higher probability of wasting and meat consumption to be associated with higher stunting probability. Milk, while highly nutritious and well established as critical for child growth, is also a reservoir for various pathogens, if not produced and prepared safely43. In Rwanda, milk is consumed in various ways: raw, pasteurized, after fermentation or home boiling. An assessment of Rwandan milk and dairy chain has indicated that 5.3% of raw milk contained Salmonella44 highlighting the need and the importance of milking hygiene, barn cleanliness and milking equipment sanitation in Rwanda45. Authors also reported that in locally marketed milk, pasteurization was less common in Rwanda. One possible explanation for the contrary results of meat consumption could be the very low prevalence of meat consumption in Rwanda (3.3%) and wasting (1.2%). However, the ASF measure was based on a cross-sectional 24-h dietary recall, which may not provide a stable estimate of actual consumption.

The regional variations in ASF consumption patterns are noteworthy as well highlighting the need to account for local realities. In Nyagatare district, stronger association of child nutrition status was observed with livestock ownership. Nyagatare is a district known for high livestock production, particularly cattle, and these findings underscore the potential role of livestock in childhood nutrition in regions where animal husbandry is prevalent. The prevalence of livestock ownership in Nyagatare (51%) was higher compared to the national average (46%) and Eastern Province (47.9%). This higher prevalence, coupled with greater milk consumption in Nyagatare (45.6% compared to 26.3% nationally), may explain the stronger protective effect against stunting in this district, as well as the absence of any cases of wasting within the district.

Egg consumption specifically was found to be positively significantly associated with underweight (in Eastern province) and wasting (in Rwanda and Eastern province) among the households who owned livestock, while egg consumption on its own was not significantly associated with any child growth outcome, raises interesting questions about the role of chicken production, specifically, on underweight and wasting. We found chicken ownership to be a significant risk factor for wasting and underweight. Numerous studies have found associations between chicken ownership and poor child growth outcomes, though many have focused on stunting39,46. The finding raises important questions about the nature of livestock ownership, including which animals producing which ASF for consumption among children, and child growth outcomes. Similar conlcusions were drawn from a systematic review by Zerfu et al. (2023) who found that cattle ownership was more often found to positively associated with human nutrition compared to poultry ownership.

In the multilevel analysis, maternal education, birth size, birth order, wealth status and elevation levels were significantly all associated with various child growth outcomes. A child born to mothers who had higher education or above was 14% less likely to be stunted than a child born to mothers with no education. Maternal education is related with many other factors that may influence children’s nutrition status including good feeding practices, childhood vaccination, and other positive health behaviors.

Conclusion

Child malnutrition in Rwanda, and especially stunting, is a major public health concern. This study tries to unpack the multifactorial relationship of social determinants of child malnutrition with human livestock relationship emebedded within the same. In the efforts to understand child malnutrition, often social determinants include socioeconomic and political factors but the environment around the household is often missed from the picture or looked at in isolation. Exposure to livestock becomes important especially in the LMICs and in rural settings where livestock is a major source of livelihood. This paper made an effort to combine the human livestock interaction with other social determinants to understand child growth malnutiriton in Rwanda.

Recent government efforts have devoted huge resources to combatting malnutrition. Findings from this study demonstrate the consistent significance of livestock ownership on improving child nutritional outcomes, especially stunting and underweight. Though the effect of ASF consumption was not consistent across its type or across regions, the positive effect was noted for children who belonged to households with livestock. The study has some limitations in terms of using cross-sectional data, 24-h recall of ASF consumption which may not fully capture long-term dietary patterns, and potential unobserved confounders. However, the findings from the study contributes to the literature by highlighting the importance of livestock in improving child nutrition in LMICs and in Rwanda. As the world strives to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), understanding the complex relationships between agriculture, livestock ownership, and nutritional outcomes becomes increasingly crucial. Our findings provide important insights for policymakers and researchers, highlighting the potential of livestock-based interventions while underscoring the need for context-specific, multifaceted approaches to addressing child malnutrition. The strong association between livestock ownership and reduced stunting, particularly in Nyagatare, highlights the potential of livestock-promoting policies to improve child nutrition in similar regions. Programs like the "One Cow Per Poor Family" initiative may yield extensive benefits for child nutrition beyond immediate economic gains as have been noted in some other studies48. However, regional variations necessitate tailored interventions that consider local contexts and agricultural practices. A multifaceted approach might include expanding livestock ownership programs in areas with high animal husbandry potential, developing targeted nutrition education programs, addressing cultural and economic barriers to ASF consumption, and integrating livestock interventions with other nutrition-sensitive strategies including behaviour change compaign. Such a comprehensive strategy would better address the complex nature of child malnutrition and leverage the benefits of livestock ownership, ultimately improving nutritional outcomes for children across diverse regions of Rwanda.

As DHS dataset only allows a cross-sectional comparison making a causal inference to be difficult, future research could benefit from interventional or longitudinal studies that can better establish the causal relationships between livestock ownership, ASF consumption and child nutrition outcomes. Longitudinal studies could capture the temporal aspects and allow researchers to track how changes in livestock ownership or ASF consumption affect child nutrition outcomes over time. Nutritional trials focusing on ASF consumption during early childhood in Rwanda can also provide causal insights as has been found in some other countries49. Similarly, interventional studies, where specific policies or programs are implemented, could help isolate the impact of these factors on nutrition, controlling for other variables and offering more robust evidence for causal claims. These research designs would strengthen the understanding of the mechanisms through which livestock and ASF consumption influence child health and development. Additionally, detailed investigations into the pathways through which livestock ownership influences nutrition, such as direct consumption of ASF, income effects, and women’s empowerment, could provide valuable insights for policy design. Studies exploring potential negative impacts of livestock ownership, such as zoonotic disease transmission, would offer a more comprehensive understanding of the livestock-nutrition nexus. Finally, research into the cost-effectiveness of livestock-based interventions compared to other nutrition-focused programs would be valuable for policymakers.

Data availability

The dataset is available from the DHS program official database www.measuredhs.com

References

Headey, D. D. & Alderman, H. H. The Relative Caloric Prices of Healthy and Unhealthy Foods Differ Systematically across Income Levels and Continents. J. Nutr. 149, 2020–2033 (2019).

Beal, T. et al. Friend or Foe? The Role of Animal-Source Foods in Healthy and Environmentally Sustainable Diets. J. Nutr. 153, 409–425 (2023).

Mkama, M. E. et al. Factors associated with under-five mortality in Rwanda: An analysis of the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2020. PLOS Glob. Public Health 4, e0003358 (2024).

Singh, A., Rahut, D. B. & Sonobe, T. Exploring minimum dietary diversity among cambodian children using four rounds of demographic and health survey. Sci. Rep. 14, 14719 (2024).

UNICEF. Nutrition, for Every Child: UNICEF Nutrition Strategy 2020–2030. (2020).

Dewey, K. G. & Begum, K. Long-term consequences of stunting in early life. Matern. Child. Nutr. 7, 5–18 (2011).

WHO. Fact sheets - Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (2024).

Akseer, N. Economic costs of childhood stunting to the private sector in low- and middle-income countries. EclinicalMedicine 45, 101320 (2022).

World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. 76 (2010).

UNICEF. UNICEF Conceptual Framework on Maternal and Child Nutrition. (1990).

Adesogan, A. T., Havelaar, A. H., McKune, S. L., Eilittä, M. & Dahl, G. E. Animal source foods: Sustainability problem or malnutrition and sustainability solution?. Perspective matters. Glob. Food Secur. 25, 100325 (2020).

Parikh, P. et al. Animal source foods, rich in essential amino acids, are important for linear growth and development of young children in low- and middle-income countries. Matern. Child. Nutr. 18, e13264 (2022).

Kaimila, Y. et al. Consumption of Animal-Source Protein is Associated with Improved Height-for-Age z Scores in Rural Malawian Children Aged 12–36 Months. Nutrients 11, 480 (2019).

Bonis-Profumo, G., do Rosario Pereira, D., Brimblecombe, J. & Stacey, N. Gender relations in livestock production and animal-source food acquisition and consumption among smallholders in rural Timor-Leste: A mixed-methods exploration. J. Rural Stud. 89, 222–234, (2022).

D’Haene, E., Vandevelde, S. & Minten, B. Fasting, food and farming: Value chains and food taboos in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16, e0259982 (2021).

Meyer-Rochow, V. B. Food taboos: their origins and purposes. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 5, 18 (2009).

Blum, L. S., Swartz, H., Olisenekwu, G., Erhabor, I. & Gonzalez, W. Social and economic factors influencing intrahousehold food allocation and egg consumption of children in Kaduna State. Nigeria. Matern. Child. Nutr. 19, e13442 (2023).

Jin, M. & Iannotti, L. L. Livestock production, animal source food intake, and young child growth: The role of gender for ensuring nutrition impacts. Soc. Sci. Med. 105, 16–21 (2014).

Pasqualino, M. M. et al. Household animal ownership is associated with infant animal source food consumption in Bangladesh. Matern. Child. Nutr. 19, e13495 (2023).

Smith, J. et al. Beyond milk, meat, and eggs: Role of livestock in food and nutrition security. Anim. Front. 3, 6–13 (2013).

Bachewe, F. N., Minten, B. & Yimer, F. The Rising Costs of Animal-Source Foods in Ethiopia: Evidence and Implications. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/rising-costs-animal-source-foods-ethiopia-evidence-and-implications (2017).

Asare, H., Rosi, A., Faber, M., Smuts, C. M. & Ricci, C. Animal-source foods as a suitable complementary food for improved physical growth in 6 to 24-month-old children in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 128, 2453–2463 (2022).

Speedy, A. W. Global Production and Consumption of Animal Source Foods. J. Nutr. 133, 4048S-4053S (2003).

Steinfeld, H., Mooney, H. A., Schneider, F. & Neville, L. E. Livestock in a Changing Landscape, Drivers, Consequences, and Responses (Island Press, 2013).

Murphy, S. P. & Allen, L. H. Nutritional Importance of Animal Source Foods. J. Nutr. 133, 3932S-3935S (2003).

Rawlins, R., Pimkina, S., Barrett, C. B., Pedersen, S. & Wydick, B. Got milk? The impact of Heifer International’s livestock donation programs in Rwanda on nutritional outcomes. Food Policy 44, 202–213 (2014).

Dumas, S. E., Kassa, L., Young, S. L. & Travis, A. J. Examining the association between livestock ownership typologies and child nutrition in the Luangwa Valley Zambia. PLoS ONE 13, e0191339 (2018).

Chen, D. et al. Benefits and Risks of Smallholder Livestock Production on Child Nutrition in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Front. Nutr. 8, 751686 (2021).

Kaur, M., Graham, J. P. & Eisenberg, J. N. S. Livestock Ownership among Rural Households and Child Morbidity and Mortality: An Analysis of Demographic Health Survey Data from 30 Sub-Saharan African Countries (2005–2015). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96, 741–748 (2017).

Sayinzoga, F. & Bijlmakers, L. Drivers of improved health sector performance in Rwanda: a qualitative view from within. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 123 (2016).

IMF. Rwanda: Poverty Reduction Strategy paper. (2013).

UNICEF. UNICEF and NCDA roll out campaign to combat malnutrition in children. https://www.unicef.org/rwanda/press-releases/unicef-and-ncda-roll-out-campaign-combat-malnutrition-children (2022).

Thornton, P., van de Steeg, J., Notenbaert, A. & Herrero, M. The Impacts of Climate Change on Livestock and Livestock Systems in Developing Countries: A Review of What We Know and What We Need to Know. Agric. Syst. 101, 113–127 (2009).

Niyonzima, T., Stage, J. & Uwera, C. The value of access to water: livestock farming in the Nyagatare District. Rwanda. SpringerPlus 2, 644 (2013).

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda - NISR, Ministry of Health - MOH, & ICF. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2019–20. https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR370/FR370.pdf (2021).

Azzarri, C., Cross, E., Haile, B. & Zezza, A. Does Livestock Ownership Affect Animal Source Foods Consumption and Child Nutritional Status? Evidence from Rural Uganda. Policy Res. Wokring Pap. 7111 World Bank Group (2014).

Dore, A. R., Adair, L. S. & Popkin, B. M. Low Income Russian Families Adopt Effective Behavioral Strategies to Maintain Dietary Stability in Times of Economic Crisis. J. Nutr. 133, 3469–3475 (2003).

Zambrano, L. D., Levy, K., Menezes, N. P. & Freeman, M. C. Human diarrhea infections associated with domestic animal husbandry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 108, 313–325 (2014).

Bardosh, K. L. et al. Chicken eggs, childhood stunting and environmental hygiene: an ethnographic study from the Campylobacter genomics and environmental enteric dysfunction (CAGED) project in Ethiopia. One Health Outlook 2, 5 (2020).

Hetherington, J. B., Wiethoelter, A. K., Negin, J. & Mor, S. M. Livestock ownership, animal source foods and child nutritional outcomes in seven rural village clusters in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agric. Food Secur. 6, 9 (2017).

Mosites, E. M. et al. The Relationship between Livestock Ownership and Child Stunting in Three Countries in Eastern Africa Using National Survey Data. PLoS ONE 10, e0136686 (2015).

Flax, V. L. et al. Animal Source Food Social and Behavior Change Communication Intervention Among Girinka Livestock Transfer Beneficiaries in Rwanda: A Cluster Randomized Evaluation. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 9, 640–653 (2021).

Kapoor, S., Goel, A. D. & Jain, V. Milk-borne diseases through the lens of one health. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1041051 (2023).

Kamana, O., Ceuppens, S., Jacxsens, L., Kimonyo, A. & Uyttendaele, M. Microbiological Quality and Safety Assessment of the Rwandan Milk and Dairy Chain. J. Food Prot. 77, 299–307 (2014).

De Vries, A., Kaylegian, K. E. & Dahl, G. E. MILK Symposium review: Improving the productivity, quality, and safety of milk in Rwanda and Nepal *. J. Dairy Sci. 103, 9758–9773 (2020).

Lowe, C., Sarma, H., Gray, D. & Kelly, M. Perspective: Connecting the dots between domestic livestock ownership and child linear growth in low- and middle-income countries. Matern. Child. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13618 (2024).

Zerfu, T. A. et al. Associations between livestock keeping, morbidity and nutritional status of children and women in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 36, 526–543 (2023).

Flax, V., Ouma, E., Poole, J., Izerimana, L. & Grant, K. Rwandan government livestock asset transfer program (‘Girinka’) is associated with improved child nutrition. Feed Future Innov. Lab Livest. Syst. (2019).

Eaton, J. C. et al. Effectiveness of provision of animal-source foods for supporting optimal growth and development in children 6 to 59 months of age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012818.pub2 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GSM and CT was involved in the conceptualization, design and drafting of the original manuscript and the formal statistical analysis. All authors, GSM, CT, FRP, KR, DA, IAA, and SLM involved in the data curation, data interpretation, and critical review of intellectual content. The manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interest.

Ethical declarations

Since the study was a secondary data analysis of publicly available survey data from the MEASURE DHS program, ethical approval and participant consent were not necessary for this particular study. We requested the DHS Program and permission was granted to download and use the data for this study from http://www.dhsprogram.com. There are no names of individuals or household addresses in the data files.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirzajonova, G.S., Tiwari, C., Paro, F.R. et al. Livestock ownership, ASF consumption and child nutrition in Rwanda: a multilevel mixed effect approach. Sci Rep 15, 30443 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97365-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97365-w