Abstract

Understanding oscillatory behavior in human networks is essential for exploring synchronization, coordination, and collective dynamics. In this study, we investigate tempo oscillations in complex human networks using a system of coupled violin players with precisely controlled network parameters. Each player interacts via delayed auditory feedback, allowing us to explore the effects of connectivity, delay, and tempo on network oscillations. We identify two distinct types of oscillations: fast (2–3 s) and slow (5–25 s), and demonstrate that their periods are independent of network size and delay but are strongly correlated with the network’s average tempo. Additionally, we show that increasing the number of coupled neighbors enhances oscillation damping, indicating the role of connectivity in stabilizing network dynamics. By varying the delay rate, we discover a critical decay rate where oscillation amplitude transitions from damping to amplification. These results provide valuable insights into the dynamic interplay of tempo, delay, and connectivity in coupled oscillator systems, with implications for applications in group dynamics, distributed systems, and synchronization processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human networks represent a complex and dynamic web of interactions between individuals, where connections are formed based on various social, cognitive, and emotional factors. These networks are not just passive structures but exhibit emergent behaviors, such as synchronization, coordination, and collective decision-making. Studying human networks is crucial because it offers insights into various fields, including social sciences, neuroscience, economics, and even politics.1 Among the key phenomena observed in these networks, oscillatory behaviors stand out as critical for understanding how individuals and groups adapt, respond to challenges, and maintain stability in dynamic environments.

Network oscillations are rhythmic fluctuations in the state of the network, which often occur when individual units in a network interact with a delay, leading to periodic changes in their tempo.1 These oscillations are significant because they reflect the network’s internal dynamics and help maintain flexibility and adaptability. In addition, network oscillations have been shown to play a vital role in brain function,2,3 neural networks,4,5 cell biology,6 disease spreading,7,8 and solar dynamics.9

Oscillations in human networks can significantly influence the dynamics of the groups and their evolution. Although several studies have examined oscillations in human networks,10 they often lack precise control over network parameters or focus on human networks with all-to-all coupling.11,12,13,14,15 In this study, we investigate network oscillations in complex human networks with meticulous control over their parameters. Using coupled violin players, we create various network configurations. The interplay between the delay, connectivity, and players’ behavioral adaptations, such as adjusting their playing tempo to match their neighbors, could lead to distinct network oscillations.10 We measure the phase, period, and amplitude of each player’s oscillations and the average oscillations of the network. Understanding the relationship between these oscillations and specific experimentally controlled parameters is key to unraveling the underlying behavioral mechanisms. Our system enables the accurate and repeatable analysis of human network dynamics, with minimal noise and precise parameter control.16,17 We demonstrate that the oscillation period depends on the network’s tempo rather than the delay between players or the network size.

In addition, understanding tempo oscillations in human networks has far-reaching real-world applications. These oscillations provide critical insights into how groups achieve synchronization and maintain coherence, even amid individual differences and external disturbances.12,14,18 Such knowledge can inform strategies to enhance teamwork and collaboration in professional environments,19 optimize communication in distributed systems,20,21 and foster resilience in social and organizational networks.22

Experimental setup

Our system for studying the dynamics of human networks consists of 16 professional violin players, each repeating the same musical phrase. To isolate their interactions, each player wears noise-canceling headphones, ensuring they cannot hear or see one another. A computerized control system governs the network’s configuration, specifying which players can hear each other, the delay in their auditory feedback, and their relative coupling strength. This setup allows us to create various network topologies, including one- and two-dimensional configurations with either bidirectional or unidirectional connections.16,17

Players are instructed to synchronize with their coupled neighbors, and we record the output from each player. The phase of each player is identified based on the corresponding note they play, with the start of the musical phrase defined as \(\varphi = 0\) and the end as \(\varphi = 2\pi\). This system enables us to investigate how human networks manage frustrated states, transition between stable configurations, and adapt to external perturbations16,17. By precisely controlling and measuring these interactions, we gain deeper insights into the dynamics of complex human networks.

We focus here on unidirectional small networks since they enable us to attribute observed tempo oscillations to specific behavioral responses, such as players adjusting their tempo based solely on immediate feedback from a single neighbor. While real-world networks are typically multidirectional and involve bidirectional feedback, understanding the dynamics in this simplified setting provides baseline insights into how individuals respond to delayed auditory feedback in a controlled environment.23 Future studies could investigate how the introduction of bidirectional and higher-dimensional connectivity further affects oscillatory dynamics. In addition, there is a direct mathematical mapping between systems with periodic motion and coordinated directional alignment of aperiodic systems.24 Therefore, our study on the synchronization of violin players with periodic behavior can be applied to other aperiodic coordinated behaviors in other systems.25,26

Results

This study focuses on the oscillations imposed on network dynamics, specifically examining networks with unidirectional coupling and periodic boundary conditions. These oscillations are demonstrated in Fig. 1 and the system is schematically shown in Fig. 1a. We measured the phase of each player over time while linearly increasing the delay between players. As the delay increases, the players slow their tempo, evident from the decreasing slope of the phase, until they reach a vortex state after approximately 30 s.

To quantify this behavior, we calculated the average derivative of the phase over time to determine the average tempo of the network, as shown in the top panel of Fig. 1b. The tempo exhibited a decreasing trend that followed a rational fitting curve, reflecting the system’s overall dynamics. However, deviations from this fit revealed oscillatory behavior. These oscillations, emphasized by subtracting the rational fit from the measured data, are presented in the bottom panel of Fig. 1b.

These oscillations were observed consistently across different network dynamics, indicating their robustness. Notably, we identified two distinct types of oscillations: slow oscillations with periods of 5–25 s and fast oscillations with periods of 2–3 s. An example illustrating these two oscillatory modes is presented in Fig. 1c.

Measuring network oscillations in coupled violin players. (a) (Inset) Schematic representation of the network, illustrating a unidirectional ring configuration of eight coupled violin players. (Graph) The phase of each player is plotted as a function of time while the delay between players is linearly increased. (b) (Top) The average tempo of all players, fitted with a rational curve to capture the overall trend. (Bottom) The relative tempo, obtained by subtracting the fit, highlights the oscillatory behavior in the tempo. (c) Examples of the measured average tempo of the network, showcasing two distinct oscillatory modes: slow oscillations with periods of up to 25 s and fast oscillations with periods of 2–3 s.

We measured these oscillations across various network sizes, analyzing both fast and slow oscillation periods, shown in Fig. 2a. We evaluated Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the slow and fast oscillations and found 0.26 and -0.16, respectively. These results indicate a low correlation so the periods of both slow and fast oscillations remain independent of network size.

To further investigate, we focused on the slow oscillations and examined their period as a function of time. These results, presented in Fig. 2b, are depicted as colored dots, with different colors representing different network sizes. The slow oscillation period exhibits a parabolic trend, increasing until approximately 25 s before decreasing. A parabolic fit to the data is shown as the black curve. Since the delay increases linearly, this parabolic shape has a correlation coefficient of 0.5 with the delay. When examining the average tempo of all networks, we observed a slowdown for about 25 s, followed by an increase as the network approaches the vortex state, as shown by the blue curve in Fig. 2b. We evaluated the correlation coefficient between the players’ tempo and the oscillations’ period and found it to be 0.86, indicating that the network oscillations are correlated with the players’ tempo but are independent of both the delay and the network size.

Measuring the network oscillations. (a) Periods of fast and slow oscillations as a function of the network size, demonstrating their independence from the size of the network. (b) Period of slow oscillations as a function of time, showing a parabolic trend, with the colored dots representing different network sizes and the black curve denotes a parabolic fit.

Next, we compare networks with higher dimensions to investigate how the number of neighbors affects the oscillation damping. We measured the amplitude of the oscillations over time and show that increasing the number of neighbors leads to greater damping of the oscillations. Figure 3a,b,c illustrate the oscillation damping for three representative networks, each with a different number of coupled neighbors. The network in Fig. 3a is a unidirectional ring network of 8 players, where each player is coupled to one neighbor. In Fig. 3b, the network is a unidirectional square lattice with 16 players, where each player is coupled to two neighbors. Finally, Fig. 3c depicts a unidirectional triangular lattice of 16 players, where each player is coupled to three neighbors. We calculate the average damping coefficient for each network, as shown in Fig. 3d. These results demonstrate that as the number of neighbors increases, the oscillations become more heavily damped.

Oscillation damping coefficients in different unidirectional networks. Representative examples of damped oscillations are shown for (a) a ring network with one coupled neighbor per player, (b) a square lattice network with two coupled neighbors per player, and (c) a triangular lattice network with three coupled neighbors per player. (d) The average damping coefficient as a function of the number of neighbors per player, illustrating that damping increases with the number of coupled neighbors. FWHM - full width at half the maximum.

In all previous experiments, we adjusted the delay change rate to a constant rate of 1 second per every 30 s of playtime. To investigate the effect of varying delay rates, we repeat the experiments using delay rates of 2 and 4 s per 30 s of playtime. The results are presented in Fig. 4, where in Fig. 4a we show the phase of the players as a function of time and in Fig. 4b we show the average tempo of the players. These results reveal distinct trends: at a delay rate of 2 s per 30 s, the amplitude of the oscillations decreases significantly, whereas at a delay rate of 4 s per 30 s, the oscillation amplitude increases. These findings suggest that the delay rate of 2 s per 30 s represents a critical decay rate, beyond which the oscillatory behavior transitions from damping to amplification.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated tempo oscillations in complex human networks using a novel system of coupled violin players with precisely controlled interactions. Our results demonstrate that network oscillations exhibit both fast and slow modes, with periods independent of network size or delay but correlated with the average tempo of the network. We also found that increasing the number of coupled neighbors leads to greater damping of oscillations, highlighting the influence of network connectivity on dynamic stability. The slow oscillations may reflect the group’s collective effort to correct substantial tempo deviations, while fast oscillations might indicate local attempts of rapid synchronization adjustments.

Furthermore, we identified a critical decay rate in the delay progression, where oscillation amplitude transitions from damping to amplification. These findings provide new insights into the interplay between tempo, connectivity, and oscillatory behavior in coupled human networks, with potential applications in understanding synchronization, group dynamics, and broader oscillator systems. Future work could explore the impact of nonlinear delay effects and extend these findings to other types of human and artificial networks.

Our findings from simplified, controlled scenarios offer foundational insights into tempo oscillation mechanisms, forming a basis upon which more intricate real-world networks can be studied. Future research incorporating bidirectional, irregular, and adaptive network configurations will further refine our understanding, ensuring broader generalization to realistic human interaction networks in social and organizational contexts.

Methods

Experimental system

Our system is based on coupling 16 violin players connected via a computer system. We record the output from each violin with a pickup microphone (Barcus-Berry True Expression Violin Piezo Pickup). These pickup microphones are connected with 10 m cables to a sound card (Focusrite Scarlett 18i20) and to an optical extension (Focusrite Scarlett OctoPre Dynamic). The sound cards are connected to a computer (MacBook Pro M3) that controls the input and decides which channel is connected to which. The output is directed from the computer through the sound card and 10 m cables to professional sound isolation earphones (Shure Se 215).

The players repeat the same musical phrase, presented in Fig. 5, and are instructed to synchronize with what they hear. We introduce delay between the players which leads them to either slow down their playing tempo, ignore their neighbor, or even stop playing altogether. While the players followed one of these options, we observed tempo oscillations which are the focus of this study. The experiments were conducted with up to 16 violin players connected in different configurations, from networks of 2 coupled players and up to networks with 16 coupled players. For networks with fewer number of players than 16, we replicate the network several times with different players. We conducted the experiments on three different days with different players.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for human research. The experimental protocols were approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 28042471). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Numerical methods and data analysis

To analyze the system, we use a note detection program that analyzes the output from each violin and writes it into a *.wav file. From this file, we obtain the phase of each player as a function of time. We define the beginning of the musical phrase as phase 0 and the end as a phase of \(2\pi\). Next, we evaluate the phase derivative of each player to identify its playing tempo as a function of time. To detect the network oscillations, we average over all the players’ tempo and obtained the average tempo of the network. This is a global property of the network and not a property of a single player.

The average tempo can either slow down or remain constant. The slowing down is following

where \(\omega\) is the average tempo difference between the players, \(\kappa\) is the coupling strength, \(\Delta t\) is the delay, and \(\varphi =\sum \varphi _n/N\) is the average phase of all oscillators.17 We evaluated the fit with the MATLAB fitting tool and subtracted this fit from the measured results. This allows us to identify the oscillations in the tempo without the slowing down trend. To analyze the oscillations, we Fourier transform the tempo as a function of time and determine the oscillations period.

Once we retrieve the oscillations, we can present them as a function of time or network size. We calculate the oscillation period of the tempo as a function of the network size and present it in Fig. 2a. However, we evaluate the correlation between the tempo oscillation period and the network size to be 0.26. Next, we evaluated the oscillation period as a function of time, and present it in Fig. 2b. We fitted the results with a parabolic fit by the fitting tool of MATLAB. This resulted in a correlation coefficient of 0.86, indicating a high correlation between the tempo oscillations’ period and the playing tempo.

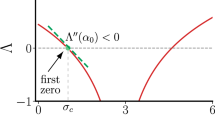

Analytical model

We model our system using the Kuramoto formalism for coupled oscillators which is the known model for analyzing periodic motion and synchronized systems:18,27,28

where \(\varphi _n(t)\) is the phase of the \(n\)th player, \(\omega _n\) is its intrinsic frequency, \(\kappa _{n,m}\) denotes the coupling strength between players \(n\) and \(m\), and \(\tau\) is the time delay in the coupling.

To explore the stability of the synchronized state, let \(\varphi _n(t) = \varphi _0 + \delta \varphi _n(t)\).29 Near a perfectly synchronized solution, \(\delta \varphi _n(t)\) represents a small perturbation from that uniform phase \(\varphi _0\). Substituting into the sine term and linearizing gives:

A common way to see how oscillations can emerge is to look for exponential solutions to the linearized equation. Specifically, assume a trial solution of the form

Substituting into Eq. (3) yields

By dividing out the common factor \(e^{\lambda t}\), we obtain a characteristic equation for \(\lambda\):

This relationship implies that \(\lambda\) can, in general, be a complex number: \(\lambda = \alpha \pm i\beta\). The imaginary component \(\beta\) of \(\lambda\) sets the frequency of small oscillations. In many such time-delay systems, the delay \(\tau\) enters the real part of \(\lambda\) most directly (affecting whether perturbations grow or decay), while the imaginary part that determines oscillation frequency often depends more on the net coupling strength and less directly on \(\tau\). Hence, in the linear regime, we see that the primary oscillation periods can emerge independently of the delay.

Physically, because the linearization focuses on small deviations around a synchronized state, the direct phase-lag effects introduced by the delay appear mainly in the growth/decay rate of these small perturbations rather than in their fundamental frequency. As a result, the period of the observed oscillations is essentially governed by the \(\kappa _{n,m}\cos (\varphi _0)\) terms (the “effective” coupling), consistent with our experimental observation that the oscillation frequency is not set by \(\tau\). This also explains why in our measurements the oscillation timescales correlate with the overall network tempo rather than the externally imposed delay.

Data availability

All the raw measured data generated in this study have been deposited in the figshare database under accession code CC BY 4.0: https://figshare.com/s/7eafddc0f047b4b5d69f.

References

Pietras, B. & Daffertshofer, A. Network dynamics of coupled oscillators and phase reduction techniques. Phys. Rep. 819, 1–105 (2019).

Buzsaki, G. & Draguhn, A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science 304(5679), 1926–1929 (2004).

Brunel, N. & Hakim, V. Fast global oscillations in networks of integrate-and-fire neurons with low firing rates. Neural Comput. 11(7), 1621–1671 (1999).

Dupret, D., Pleydell-Bouverie, B. & Csicsvari, J. Inhibitory interneurons and network oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105(47), 18079–18080 (2008).

Gao, Y. & Wang, J. Oscillation propagation in neural networks with different topologies. Phys. Rev. E-Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 83(3), 031909 (2011).

Loewenstein, Y., Yarom, Y. & Sompolinsky, H. The generation of oscillations in networks of electrically coupled cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98(14), 8095–8100 (2001).

Li, X. & Wang, X. Controlling the spreading in small-world evolving networks: Stability, oscillation, and topology. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 51(3), 534–540 (2006).

Yang, F., Zhang, R., Yao, Y. & Yuan, Y. Locating the propagation source on complex networks with propagation centrality algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 100, 112–123 (2016).

Harvey, J. et al. The global oscillation network group (gong) project. Science 272(5266), 1284–1286 (1996).

Wang, L., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y. & Li, X. How human location-specific contact patterns impact spatial transmission between populations?. Sci. Rep. 3(1), 1468 (2013).

Helbing, D., Farkas, I. & Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 407(6803), 487–490 (2000).

Néda, Z., Ravasz, E., Brechet, Y., Vicsek, T. & Barabási, A.-L. The sound of many hands clapping. Nature 403(6772), 849–850 (2000).

Strogatz, S. H., Abrams, D. M., McRobie, A., Eckhardt, B. & Ott, E. Crowd synchrony on the millennium bridge. Nature 438(7064), 43–44 (2005).

Oullier, O., De Guzman, G. C., Jantzen, K. J., Lagarde, J. & Scott Kelso, J. Social coordination dynamics: Measuring human bonding. Soc. Neurosci. 3(2), 178–192 (2008).

Fairhurst, M. T., Janata, P. & Keller, P. E. Being and feeling in sync with an adaptive virtual partner: Brain mechanisms underlying dynamic cooperativity. Cerebral Cortex 23(11), 2592–2600 (2013).

Shahal, S. et al. Synchronization of complex human networks. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 3854 (2020).

Shniderman, E. et al. How synchronized human networks escape local minima. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 9298 (2024).

Strogatz, S. H. From Kuramoto to Crawford: Exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators. Physica D Nonlinear Phenomena 143(1–4), 1–20 (2000).

Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E. & Zaccaro, S. J. A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 26(3), 356–376 (2001).

Olfati-Saber, R., Fax, J. A. & Murray, R. M. Consensus and cooperation in networked multi-agent systems. Proc. IEEE 95(1), 215–233 (2007).

Arenas, A., Díaz-Guilera, A., Kurths, J., Moreno, Y. & Zhou, C. Synchronization in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 469(3), 93–153 (2008).

Albert, R., Jeong, H. & Barabási, A.-L. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 406(6794), 378–382 (2000).

D’Ausilio, A., Novembre, G., Fadiga, L. & Keller, P. E. What can music tell us about social interaction?. Trends Cognit. Sci. 19(3), 111–114 (2015).

Lyu, H., Sha, N., Qin, S., Yan, M., Xie, Y. & Wang, R. Advances in neural information processing systems. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 32 (2019).

Nixon, M., Ronen, E., Friesem, A. A. & Davidson, N. Observing geometric frustration with thousands of coupled lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110(18), 184102 (2013).

Gelblum, A. et al. Ant groups optimally amplify the effect of transiently informed individuals. Nat. Commun. 6(1), 7729 (2015).

Acebrón, J. A., Bonilla, L. L., Vicente, C. J. P., Ritort, F. & Spigler, R. The Kuramoto model: A simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev. Modern Phys. 77(1), 137 (2005).

Kuramoto, Y. & Nishikawa, I. Statistical macrodynamics of large dynamical systems. Case of a phase transition in oscillator communities. J. Stat. Phys. 49(3–4), 569–605 (1987).

Cohen, A. B. et al. Dynamic synchronization of a time-evolving optical network of chaotic oscillators. Chaos Interdiscipl. J. Nonlinear Sci. 20(4), 043142 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank: Prof. Yuval Garini and Tal Yizreal and the Fetter Museum of Nanoscience and Art at Bar-Ilan University for establishing the collaboration; Transmeet Art and Science Festival, and the Steinhart Museum of Natural History for hosting the art event; Amir Bolzman and Lars Sargel were the sound engineers; Prof. Ofer Feinerman for fruitful discussions; and funding by the Yeda-Sela Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S. and M.F. conceived the experiments, E.S, H.D. and M.F designed the experiments, E.S designed the computer code, M.W, and S.G. conducted the experiments, E.S and M.F. analysed the results. E.S and M.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shniderman, E., Wertsman, M., Granot, H. et al. Tempo oscillations in rhythmic human networks. Sci Rep 15, 22231 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97438-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97438-w