Abstract

Episodic autobiographical memory involves the ability to travel along the mental timeline, so that events of our own life can be recollected and re-experienced. In the present study, we tested the neural underpinnings of mental travel across past and future autobiographical events by using a spatiotemporal interference task. Participants were instructed to mentally travel across past and future personal (Episodic Autobiographical Memories; EAMs) and Public Events (PEs) during Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). We found that a distributed network of brain regions (i.e., occipital, temporal, parietal, frontal, and subcortical regions) is implicated in mental projection across past and future independently from the memory category (EAMs or PEs). Interestingly, we observed that most of these regions exhibited a neural modulation as a function of the lifetime period and/or as a function of the compatibility with a back-to-front mental timeline, specifically for EAMs, indicating the key role of these regions in representing the temporal organization of personal but not public events. Present findings provide insights into how personal events are temporally organized within the human brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental Time Travel is the individuals’ ability to project themselves in the past and to imagine themselves in the future. It allows the development and the maintenance of autonoetic consciousness, namely “the kind of consciousness that mediates an individual’s awareness of his or her existence and identity in subjective time extending from the personal past through the present to the personal future”1. The cognitive architecture underlying mental time travel rests its foundation on the organization of autobiographical knowledge, which provides a personal timeline, along which autobiographical information is temporally organized in spatial terms2. According to Conway and Pleydell-Pearce3, autobiographical knowledge is represented as a partonomic hierarchy. At the top, lifetime periods correspond to general knowledge about significant others and activities, usually spanning in the range of months or years (e.g. the time I spent at the Neuroimaging Center as a PhD student). Then, general events include knowledge about repeated events or events that are extended in time (e.g. my trip to Tampere for the Meeting of the European Societies of Neuropsychology in 2016); finally, event-specific knowledge corresponds to memory for experiences with a unique spatial and temporal context (e.g. the social dinner during the European Workshop on Imagery and Cognition in 2016). Autobiographical knowledge may be navigated vertically between different layers, for example zooming in a specific period to mentally represent a specific event, or horizontally, for example, jumping from one event to another. Mental Time Travel may occur within all the layers, and the level of specificity depends on which layers of autobiographical representations are activated, with more abstracted ones corresponding to the lifetime periods.

According to D’Argembeau2 past and future thoughts rely on a similar neurocognitive architecture, corresponding to the autobiographical knowledge base theorized by Conway and Pleydell-Pearce3. Episodic Autobiographical Memory (EAM), namely the ability to recollect and re-experience events of our own life that occurred at a particular time and place, and Episodic Future Thinking (EFT), namely the ability to project the self forward in time to pre-experience an event, rely on the same core network in the brain, show parallel developmental trajectories along the lifespan, may be similarly impaired in amnesic patients and are characterized by the same phenomenological properties. Using a coordinate-based meta-analysis, Benoit and Schacter4 found that EAM and EFT consistently activate the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, insula, posterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, posterior inferior parietal cortex, orbital inferior frontal gyrus, and dorsolateral occipital cortex. Importantly, developmental studies show that EAM and EFT emerge in tandem in children between 3 and 5 years5. Also, EAM and EFT show a similar decline in aging6. Data from patients with amnesia, even though not always consistent (see for example7), support the idea that hippocampal damage may yield to deficits in both EAM and EFT8,9. Finally, the representations of both past and future events are affected by temporal distance, namely events that are closer in time yield to a stronger feeling of re-experiencing (or pre-experiencing) than events that are farther from the present10. Stillman and colleagues11 showed different patterns of activation during the imagination of future events depending on whether they were imagined happening tomorrow, or five years from now. Events closer to the present moment elicited higher activation of the precuneus and cingulate gyrus. Instead, events that are far from the present time yield to higher activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, cerebellum, angular gyrus, lateral occipital cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortices, middle temporal gyrus, occipital cortex, and inferior frontal gyrus. However electrophysiological data by Colás-Blanco and colleagues12 suggest that the effect of temporal distance is not exactly the same for past and future events in the late parietal component (LPC) and the late frontal effect (LFE), which are involved in episodic and monitoring processes, respectively. Indeed, imaging future events that are closer to the present yields to a larger LPC compared with events that are farther in the future, with no differences between near and far past events. Also, near past events yield to a larger LFE component than past events which are farther, with no other differences for future events, both yielding to an effect that is similar to that observed for near past events.

Further insights on brain regions and networks supporting the temporal organization of personal events are provided by studies investigating neural correlates of autobiographical retrieval in individuals with Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) - a condition characterized by an extraordinary ability to remember autobiographical events in detail. When asked to access memories of autobiographical events pointed at by specific temporal coordinates, HSAM show increased connectivity of the ventromedial and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and of the temporoparietal junction, compared with control participants, suggesting that these patterns may be responsible for their more efficient access to memories cued by temporal coordinates13. These findings are consistent with evidence of enhanced resting-state connectivity of midline regions involved in the autobiographical memory network in HSAM participants14. The extraordinary ability of these individuals to recall temporal coordinates of events is further reflected in the enhanced discriminability of neural patterns supporting new and old memories in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex15.

Similarities between EFT and EAM partially apply to the individuals’ ability to project themselves towards past and future events and to temporally order the same events. In 2015, D’Argembeau and colleagues16 found that the same network of brain regions, consisting of middle and inferior temporal gyri, medial orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, postcentral gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and middle cingulate cortex, is involved in temporal ordering of past and future events. Neuropsychological data from patients with brain damage further point towards a pivotal role of the prefrontal cortex in mental travel toward future events. Indeed, patients with focal lesions to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex are selectively impaired in mentally projecting themselves in the future17. However, little is known about the fine-grained spatiotemporal dynamics of mental travel across the mental timeline.

Here we aimed at testing neural underpinnings of mental travel across past and future autobiographical events, as a function of temporal reference and distance. To this aim, we asked participants to mentally travel across their own past and future personal (Episodic Autobiographical Memories; EAMs) and Public Events (PEs) during functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI). Notably, recent behavioral evidence supports the possibility that EAMs may be selectively organized according to a sagittal mental timeline, that is, with future and past events being represented respectively as in front of us vs. at our back. In a previous study using a spatial compatibility task, we found that participants were less accurate in judging the order of EAMs when the response direction was not compatible with a sagittal mental timeline (i.e. when they had to provide a “forward” response for a relatively past event and a “backward” response for a relatively future one)18. This effect was not observed when participants judged the order of personal semantic memories, in line with the possibility that only events that are represented with a high level of contextual specificity are organized along a sagittal mental timeline. Thus, in order to assess brain correlates of such a spatiotemporal organization, in the present fMRI study participants traveled along their EAMs and PEs in two conditions, one compatible and one non-compatible with a sagittal mental timeline. Using this task, we expected to prompt the phenomenological features described above, namely the effect of the temporal distance of events (i.e. near and far periods) which would yield to different profiles of activation in the brain network supporting mental travel across EAMs and PEs. We expected to see differences in regional activation between temporal distances (NP and/or NF > FP and/or FF) and a compatibility effect (NC > N), but that these effects are more pronounced with EAMs than PEs and that this modulation mirrors the one described by previous studies on EAM and Episodic Future Thinking using different methodologies10,11,12, shading also some light upon the similarities and differences occurring between projecting towards past and future12. The functional coupling between the nodes of the EAM-related network would change as a function of the temporal features of the events, namely temporal distance.

Methods

Participants

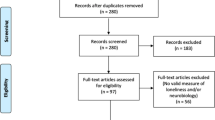

Twenty-three healthy young volunteers (mean age = 24.50 years, SD = 2.93; 11 women) took part in the study. The sample size of this study was determined based on a previous study18. First, we calculated the effect size of the previous study (η2p = 0.231) and then estimated the required sample size using G*Power (Version 3.1.9.7;19) with default parameters (α = 0.05, 1−β= 0.95), which resulted in a sample size of n = 22. The final sample size (n = 23) is comparable to that used in other fMRI studies employing a standard mass-univariate approach20,21,22,23. All participants were right-handed, as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory24, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. All volunteers gave their written informed consent to participate in this study. The experimental protocol was approved by the local research ethics committee of the IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia in Rome (Prot. CE/PROG.824) and Institutional Review Board of the Department of Psychology (Prot. N. 0000512), according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study has been preregistered at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GAQ5M.

Stimuli collection

We used an adapted version of the Autobiographical Fluency Task25,26 to collect stimuli to be presented during fMRI. Outside the scanner, we asked participants to report personal events (EAMs, i.e., getting married) and public events (PEs; i.e., September 11 attacks) for each of 4 possible periods, theoretically defined based on a previous meta-analysis27. The periods were as follows: far past (more than 5 years ago), near past (the last 12 months), near future (the next 12 months), and far future (more than 5 years from now). Participants were asked to report EAMs that occurred/may occur in these periods and PEs they remembered from these periods, or they think that may occur in the future, as many as possible. For each combination of period and memory category, the time limit was 90 s. They were also instructed to provide, for each event, a personalized label that was meaningful to them and that allowed them to unambiguously identify the specific EAM or PE. For both personal and public events, participants were instructed to report only events that occurred at a specific time and place25,26; see also23, for a similar procedure). After task completion, participants were asked to report when the events occurred or were supposed to occur in the future (respectively, the year for the far past and future periods, and the month for the near past and future periods). The whole procedure lasted ∼30 min.

The first two items reported for each period and memory category were used in the fMRI task, assigning them randomly to the compatible and noncompatible conditions (see below). Different labels were presented across conditions (compatible and noncompatible) to avoid spurious effects because of item repetition. However, items from the same periods were presented in different conditions, thus allowing to control for the effects of age/remoteness between EAMs and PEs.

fMRI task

We used a factorial 2 × 4 × 2 design, with Memory Category (Episodic Autobiographic Memory or EAM vs. Public Event or PE), Period (Far Past or FP, Near Past or NP, Near Future or NF, and Far Future or FF) and Task Condition (Compatible with the mental timeline or C and Noncompatible with the mental timeline or NC) as factors.

During fMRI, labels corresponding to EAMs and PEs (see above for details about stimuli collection) were presented one at a time, in an unbroken sequential manner, in four serially balanced sequences (see23 for a similar procedure).

In each trial, participants were instructed to decide whether the currently presented stimulus preceded or followed the previously shown stimulus in chronological order (i.e., along their personal timeline). Responses were collected using a two-button MRI- compatible keypad. In the compatible condition, participants were instructed to press the “backward” button if the current stimulus temporally preceded the previous one and the “forward” button if it followed the previous one; this mapping was reversed in the non-compatible condition (backward/forward responses for EAMs/enPS following/preceding the previous one; see also18,23 for a similar task). Reaction times (RTs) from one participant were not registered because of technical problems in data collection.

For each participant, four runs were acquired. Compatible and noncompatible conditions were presented in different runs to ensure that participants were properly engaged in the required task. Written instructions were presented at the beginning of each run. The order of the four runs was counterbalanced across participants. Within each run, labels referring to EAMs and PEs were presented in different blocks. Each block lasted 25,000 msec and contained 10 labels, each of them was presented for 2000 msec, followed by a fixation period of 500 msec. A fixation point was also presented during the inter-block intervals (IBI), lasting from 16,550 to 20,000 msec (mean IBI of 18250 msec). Stimuli were generated using E-Prime 3.0 (Psychology Software Tools) and projected on a translucent screen that participants saw through a mirror. Both accuracy and RTs were collected.

Immediately before fMRI, outside the scanner, participants underwent a short familiarization session with the same structure of the experimental task. Presented labels during this phase were created by the experimenters and referred to standard EAMs and PEs (e.g. “First child”, “Retirement”, for past and future EAMs, and “9/11”, “World peace”, for past and future PEs). All participants were presented with the same standard labels during the familiarization session. A total number of 10 trials for each combination of Memory Category and Period and Task Condition were presented during familiarization.

Image acquisition

MR images were acquired at the Santa Lucia Foundation (Rome, Italy) using a high-performance 3 T scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma) equipped with a 32-channel head coil. Functional T2*-weighted, whole-brain MR images were acquired with a gradient-echo EPI sequence, a multiband factor of 4, and an isotropic voxel size of 2.23 mm3 (60 slices, field of view = 208 × 208 mm2, repetition time [TR] = 1100 ms, echo time [TE] = 30 ms, flip angle = 65°, no in-plane acceleration;28,29,30)

For each run, we acquired 280 fMRI volumes, not including five dummy scans before each run, which were discarded. T1-weighted structural images were acquired on each subject using an MPRAGE (magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo) sequence with perspective motion correction and selective reacquisition of data corrupted by motion based on interleaved 3-D EPI navigators31,32. Volumetric imaging included 176 slices, isotropic resolution = 13 mm3, TR = 2500 ms, TE = 2 ms, inversion time = 1070 ms, flip angle = 8°.

Two spin-echo EPI volumes with phase encoding in opposite directions, no multiband acceleration, and the same geometrical and sampling properties of functional runs were acquired for field mapping (TE = 80 ms, TR = 7000 ms). A single-band reference (SBRef) image associated with the BOLD series was acquired during the pre-scan of each data run as the reference image.

The MRI acquisition included other scans not used for the present study.

Image preprocessing

Results included in this manuscript come from preprocessing performed using fMRIPrep 22.2.133; RRID: SCR_016216), which is based on Nipype 1.8.534; RRID: SCR_002502). The description below is an excerpt from the text automatically generated by fMRIPrep with the express intention to be copied and pasted into manuscripts. It is released under the CC0 license.

Anatomical data preprocessing. The T1-weighted (T1w) image was corrected for intensity non-uniformity (INU) with N4BiasFieldCorrection35, distributed with ANTs 2.3.3 (RRID: SCR_004757), and used as T1w-reference throughout the workflow. The T1w-reference was then skull-stripped with a Nipype implementation of the antsBrainExtraction.sh workflow (from ANTs), using OASIS30ANTs as target template. Brain tissue segmentation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), white-matter (WM) and gray-matter (GM) was performed on the brain-extracted T1w using fast (FSL 6.0.5.1:57b01774, RRID: SCR_00282336), . Brain surfaces were reconstructed using recon-all (FreeSurfer 7.2.0, RRID: SCR_00184737), , and the brain mask estimated previously was refined with a custom variation of the method to reconcile ANTs-derived and FreeSurfer-derived segmentations of the cortical gray-matter of Mindboggle (RRID: SCR_00243838), .

Volume-based spatial normalization to one standard space (MNI152nLin2009cAsym) was performed through nonlinear registration with `antsRegistration` (ANTs 2.3.3), using brain-extracted versions of both T1w reference and the T1w template. The following template was selected for spatial normalization: *ICBM 152 Nonlinear Asymmetrical template version 2009c* [@mni152nlin2009casym, RRID: SCR_008796; TemplateFlow ID: MNI152nLin2009cAsym].

Functional data preprocessing. For each of the BOLD scans acquired per subject (across all tasks), the following preprocessing was performed. First, a reference volume and its skull-stripped version were generated by the single-band reference (SBRef). Head-motion parameters with respect to the BOLD reference (transformation matrices, and six corresponding rotation and translation parameters) are estimated before any spatiotemporal filtering using `mcflirt` [FSL 6.0.5.1:57b01774, @mcflirt]. The estimated *fieldmap* was then aligned with rigid-registration to the target EPI (echo-planar imaging) reference run. The field coefficients were mapped on to the reference EPI using the transform. BOLD runs were slice-time corrected to 0.504s (0.5 of slice acquisition range 0–1.01 s) using `3dTshift` from AFNI [@afni, RRID: SCR_005927]. The BOLD reference was then co-registered to the T1w reference using `bbregister` (FreeSurfer) which implements boundary-based registration [@bbr]. Co-registration was configured with six degrees of freedom. First, a reference volume and its skull-stripped version were generated using a custom methodology of fMRIPrep.

For each time series, framewise displacement (FD) was computed using the implementations in Nipype (following the definitions by39). These values were obtained from the realignment parameters estimated during the preprocessing phase and indicated the amount (in mm) of head movement relative to the previous time point. FD values were included as nuisance regressors in all the BOLD analyses to reduce motion-induced artifacts.

Image analysis

Functional images were analyzed for each participant separately on a voxel-by-voxel basis, according to the general linear model (GLM) using SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). Separate regressors were included for each combination of Memory Category (EAM and PE), Period (FP, NP, NF, FF), and Task Condition (C, NC).

To have a general picture of brain regions involved in the task, we first looked at brain regions more implicated in at least one experimental condition as compared to the baseline. The resulting “omnibus” F-contrast was thresholded at p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons based on family-wise error (FWE), with a cluster size > 20 voxels.

For each subject and region, we computed a regional estimate of the amplitude of the hemodynamic response in each experimental condition by entering a spatial average (across all voxels in the region) of the pre-processed time series into the individual GLMs.

Finally, the regional hemodynamic responses were analyzed by means of a series of repeated-measures ANOVAs with Memory Category (EAM and PE), Period (FP, NP, NF, FF), and Task Condition (C, NC) as factors. For each ANOVA, after finding significant interactions, post-hoc comparisons were computed by applying Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

An FDR procedure40 was used to account for multiple comparisons: the distributions of p values obtained in each brain region and for each effect were used to compute a p threshold that set the expected rate of falsely rejected null hypotheses to 5%.

Regional hemodynamic responses, as well as behavioral data (see below), were analyzed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 25).

Psychophysiological interaction analysis

The description of the Psychophysiological Interaction Analysis below is derived from the text automatically generated by Conn with the express intention to be copied and pasted into manuscripts. It is released under a Public Domain Dedication license (CC0 1.0). Psychophysiological Interaction Analysis was performed using CONN41; RRID: SCR_009550) release 22.a42) and SPM43; RRID: SCR_007037) release 12.7771. Functional data were denoised using a standard denoising pipeline44 including the regression of potential confounding effects characterized by white matter timeseries (5 CompCor noise components), CSF timeseries (5 CompCor noise components), FD regressors (1 components), and linear trends (2 factors) within each functional run, followed by high-pass frequency filtering of the BOLD timeseries45 above 0.008 Hz. CompCor46,47 noise components within white matter and CSF were estimated by computing the average BOLD signal as well as the largest principal components orthogonal to the BOLD average within each subject’s eroded segmentation masks.

According to the main hypotheses, psychophysiological interaction analysis was used to study changes in functional connectivity across the four periods of EAM (i.e. EAM FP, EAM NP, EAM NF, and EAM FF), averaging Task Condition (C and NC). Seed regions included 30 ROIs which showed Memory Category by Period interaction. Separately for each pair of seed and target areas, a generalized psychophysiological interaction model (gPPI;48,49) was defined with seed BOLD signals as physiological factors, boxcar signals characterizing each individual task condition convolved with an SPM canonical hemodynamic response function as psychological factors, and the product of the two as psychophysiological interaction terms. Functional connectivity changes across conditions were characterized by the multivariate regression coefficient of the psychophysiological interaction terms in each model. According to the main hypotheses, at the group level we tested the effect of the Timeline, comparing Far vs. Near and Past vs. Future conditions. ROI-to-ROI parametric maps were thresholded using non-parametric statistics (cluster-level inferences, Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement50) connection threshold: p < 0.01-FWE corrected (TFCE).

Results

Behavioral results

Both accuracy and RTs in the temporal ordering task were analyzed by means of within-subject ANOVAs with Memory Category (EAM and PE), Period (FP, NP, NF, FF), and Task Condition (C, NC) as factors.

For what concerns accuracy, we applied the arcsine square root transformation to the proportion of correct responses in order to normalize proportion-based data and stabilize variance51.

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the behavioral results on both accuracy (Suppl. Figure 1A) and reaction times (Suppl. Figure 1B).

The ANOVA on accuracy revealed a main effect of Period (F3,66 = 15.96; p < 0.0001; η2p = 0.42), reflecting a linear decrease of accuracy as a function of time (FP > NP > NF; p < 0.05), with a rebound of accuracy for far future items (FF > NF; p = 0.0001; see Suppl. Figure 1 A). We also observed a main effect of Task Condition (F1,22= 5.14; p = 0.034; η2p = 0.19), reflecting higher accuracy for compatible as compared to noncompatible conditions (see Suppl. Figure 1 A). There was no significant main effect of Memory Category (F1,22= 2.56; p = 0.124; η2p = 0.10), nor significant interactions among factors (Memory Category by Period interaction: F3,66= 1.20; p = 0.316; η2p = 0.05; Memory Category by Task Condition interaction: F1,22= 0.49; p = 0.488; η2p = 0.02; Period by Task Condition interaction: F1,22= 1.47; p = 0.337; η2p = 0.05; Memory Category by Period by Task Condition interaction: F3,66= 0.54; p = 0.658; η2p = 0.02).

The ANOVA on mean reaction times revealed the main effects of Memory Category (F1,21= 16.418; p = 0.001; η2p = 0.44), Period (F3,63= 8.61; p < 0.0001; η2p = 0.29) and Task Condition (F1,22= 82.21; p < 0.0001; η2p = 0.79). Interestingly, we found significant Memory Category by Period (F3,63= 4.20; p = 0.009; η2p = 0.17), Period by Task Condition (F3,63= 4.82; p = 0.004; η2p = 0.19), and Memory Category by Period by Task Condition (F3,63= 7.31; p < 0.0001; η2p = 0.26) interactions. The three-way interaction revealed that participants responded faster to EAM as compared to PE stimuli, especially in the compatible condition which referred to the “near” time periods (NP: p < 0.0001; NF: p = 0.01; Suppl. Figure 1B). We also observed faster reaction time for EAM as compared to PE stimuli in the non-compatible condition of the FF period (p < 0.0001; Suppl. Figure 1B).

fMRI results

Figure 1 shows an “omnibus” F-contrast (any condition > baseline) revealing the involvement of a distributed network including bilateral occipital, temporal, parietal, and frontal activations (Fig. 1A) as well as subcortical activations (Fig. 1B).

Activation maps. Regions activated by the “omnibus” F-contrast (any condition > baseline), as highlighted using SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.Ac.uk/spm), is shown. (A). Cortical activations are rendered over flatted representation of both left and right hemispheres of Conte69 surface-based atlas. (B) Subcortical activations are rendered on the coronal and transversal slices of the brain volume. Regions are labeled as followed: EVC early visual cortex, FG fusiform gyrus, LG lingual gyrus, RSC retrosplenial complex, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, MTG middle temporal gyrus, pCU dorsal precuneus, IPS intraparietal sulcus, AG angular gyrus, postCG postcentral sulcus, inf postCG inferior postcentral sulcus, CS central sulcus, pCG precentral sulcus, SFG superior frontal gyrus, aMFG anterior part of the middle frontal gyrus, IFG inferior frontal gyrus, Ins Insula, SMA supplementary motor area, HC hippocampus.

The occipital activation included a wide portion of cortex, i.e., the early visual cortex (EVC), in correspondence and around the calcarine cortex, the cuneus and the posterior part of the occipital lobe. This activation extended ventromedially to include the fusiform (FG) and the lingual (LG) gyri and dorsally along the parieto-occipital sulcus, in a location remarkably coincident with the scene-selective retrosplenial complex (RSC). The temporal activation encompassed the bilateral inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and the middle temporal gyrus (MTG) of the left hemisphere. The parietal activation included the posterior part of the right dorsal precuneus (pCU), and a large swath of activation encompassing bilaterally the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) and the angular gyrus (AG). Moving anteriorly, the parietal activation extended into the somatosensory and motor cortex of the left hemisphere, thus including the left postcentral sulcus (postCG), the left inferior postcentral sulcus (inf postCG) and the adjoining central sulcus (CS), in correspondence of the hand territory of the left primary motor cortex. This frontal activation extended bilaterally into the precentral sulcus (pCG) and the adjacent superior (SFG) and inferior frontal (IFG) gyri and into the anterior portion of the middle frontal gyrus (aMFG) of the right hemisphere. Bilateral foci of activation were observed in the anterior Insula (Ins). Moving medially, the frontal activation included the bilateral supplementary motor area (SMA). Subcortical activations included the bilateral hippocampus (HC), especially its caudal most part, as well as the cerebellum where large swaths of activations were observed bilaterally in both the lateral cerebellum and the medial vermis. The anatomical location of local maxima52 in each of these brain regions is shown in Table 1.

Plots in Figs. 2, 3 and 4 show the percent signal change for each of the above-mentioned brain regions as a function of Memory Category (EAM and PE), Period (FP, NP, NF, FF), and Task Condition (C, NC). Statistical results from the 2 × 4 × 2 ANOVAs for each brain region are detailed in Table 2. After applying an FDR procedure to correct for multiple comparisons, the statistical results revealed that most of the investigated regions (bilateral EVC, FG, LG, RSC, HC, pCG, cerebellum, vermis, IFG, SMA, SFG, inf postCG, INS and right AG, IPS, aMFG) showed a significant Memory Category by Period interaction, indicating that the Period effect (NP and/or NF > FP and/or FF; p < 0.05) is selective (or more evident) for EAM (Figs. 2 and 3). Some of these regions (right IPS, SMA, aMFG, IFG, and SFG) also showed a significant Memory Category by Task Condition interaction, indicating that the effect of Task Condition (NC > C; p < 0.05) is selective for EAM (Fig. 3). Also the right ITG showed a significant Memory Category by Task Condition interaction, but it indicated a preference for PE as compared to EAM, but only for the compatible condition (p = 0.017). Finally, a different set of regions showed no significant interactions between factors, but only a main effect of Memory Category (PE > EAM; p < 0.05: in left MTG, CS, see Fig. 4A) or a main effect of Period (NF > FF; p < 0.05: in the left AG; Fig. 4B; see also Table 2) or both main effects (PE > EAM; p < 0.05 and NF > FF; p < 0.05 in the right pCu; Fig. 4C; see also Table 2). Although also the left IPS showed both Memory Category and Period main effects (Fig. 4C; see also Table 2), Bonferroni-corrected post hocs did not reveal significant differences between levels of factor Period, but only a marginal significance preference for NF vs. FF (p = 0.077). No region showed significant Period by Task Condition or Memory Category by Period by Task Condition interactions. Only significant and FDR-corrected results were considered. Significant, but FDR-uncorrected, results are also reported in Table 2. See Table 2 for further information (F, p, and η2p) about the statistical results.

Activation profile. Brain regions exhibiting a significant interaction between Memory Category (EAM and PE) and Period (FP, NP, NF, FF) are shown. For labels see Fig. 1.

Activation profile. Brain regions exhibiting a significant interaction between Memory Category (EAM and PE) and Task condition (C, NC) are shown. For labels see Fig. 1.

Activation profile. Brain regions exhibiting a main effect of (A) Memory Category (EAM and PE), (B) Period (FP, NP, NF, FF), and (C) both main effects are shown. For labels see Fig. 1.

Results from psychophysiological interaction analysis revealed a cluster of 11 connections among 6 ROIs which showed higher functional coupling for near than far EAMs (Table 3). In brief, HC-RH, FG-RH and LG-LH showed stronger functional coupling with AG-RH and IPS-RH, whereas Cerebellum-LH showed higher functional coupling with HC-RH, AG-RH, IPS-RH, FG-RH and LG-LH.

Discussion

The present fMRI study was aimed at disclosing the neural network involved in mental travel across episodic autobiographical memories and, within this network, unveiling the role of temporal features of the events. To this aim, we used a spatiotemporal compatibility task, previously used to test the existence of a sagittal mental timeline in the domain of autobiographical memories. Recent evidence, indeed, suggests that specifically EAMs are affected by spatiotemporal interference, i.e., lower accuracy is observed in judging the order of EAMs when the response direction is not compatible with a sagittal mental timeline18. By asking participants to mentally travel across their own past and future personal (Episodic Autobiographical Memories; EAMs) and public events (PEs), we tested the brain networks supporting such a spatial organization.

We observed that a distributed network of cortical and subcortical regions is implicated in mental projection across past and future EAMs and PEs. This network, which includes bilateral clusters of activation in the occipital, parietal, temporal and frontal lobes, has been typically associated with remembering past events and imagining future events (for reviews, see53,54,55).

Some of these regions (EVC, LG, FG, RSC, IPS-RH, AG-RH, ITG, infpostCG, pCG, Ins, IFG, SFG, aMFG) showed a significant Memory Category by Period interaction, indicating that the effect of the time period (a different signal modulation as a function of the four periods, i.e., far past, near past, near future, far future) was selective, or particularly evident, for episodic autobiographical memories rather than for memories of public events.

A strong modulation as a function of time period during mental travel across autobiographical memories was observed in the occipital lobe, in correspondence of the early visual cortex (EVC). This activation, which is typically observed during tasks relying on EAM56,57,58,59, could be associated with the construction of a visual scene to support the recollection of autobiographic episodes60. Interestingly, EVC activation has been associated with visual mental imagery (see61,62 for reviews), and this ability to access the perceptual information from memory to recreate the visual scene is fundamental in the mental time travel along both EAMs and PEs.

Also, a series of ventromedial regions, including lingual, parahippocampal and retrosplenial areas, showed a modulation as a function of the personal timeline, but not or less evident for mental travel across public events. Such regions are known to be pivotal for autobiographical memory, being particularly involved in mapping events in their spatial and temporal context63, as well as in supporting the generation of spatially coherent scenes in service of both environmental navigation and episodic memory64,65,66. A very prominent modulation as a function of timeline was observed in the ventral part of the parieto-occipital sulcus, in correspondence of the retrosplenial complex. This region exhibited an increase of activation for time periods close to the present (near past and near future) as compared to time periods that are far from the present (far past and far future), indicating a role in memorizing the temporal sequences of events. Beyond its role in spatial coding67,68,69,70, it has been recently proposed that the RSC might play a broader role in memory processing, since it represents both spatial and temporal information71,72,73. Specifically, it has been hypothesized that the RSC is critical for the establishment of the rich spatiotemporal contexts necessary for episodic memory (see74 for a recent review). Support to this view comes from a series of studies showing that the RSC is essential for encoding the temporal context of novel items75 and that the glucose metabolism in RSC is typically associated with temporal disorientation among Alzheimer’s patients76.

A further region showing a selective modulation as a function of time during EAM was the hippocampus. This finding confirms the idea that hippocampal representations are flexible and generalize across domains of space and time to support memory77,78,79,80. Previous evidence suggests that the hippocampus encodes not only spatial but also temporal information: it contains “time cells”, i.e., neurons firing at specific timepoints81 and supports the temporal organization of episodes82. A series of studies investigated the hippocampal role in organizing individual episodic memories by using naturalistic procedures, which allowed to automatically capture photographs from the participants’ lives through wearable cameras83,84,85. For example, Nielson and co-workers85 demonstrated that the (anterior) hippocampus represents the spatial and temporal location of memories for real-life events at scales of up to 30 km and a month of time, supporting the existence of a precise spatiotemporal organization for episodic autobiographical memories.

Besides a significant memory category by period interaction, a series of right-lateralized temporo-parieto-frontal regions also showed a Memory category by Condition interaction, indicating that the compatibility effect (NC > N) was selective for EAM. The current findings suggest that cortical regions as the SMA, and the frontal gyrus (the anterior, inferior and superior divisions) are involved in the temporal ordering of autobiographical memories. Such frontal regions have been previously implicated in mental time travel along lifetime periods23, and in projecting themselves to different time-points on the past and future along a spatialized temporal representation (i.e. the mental timeline)86. In particular, the stronger activation observed for events when the response was not compatible with the sagittal mental timeline might suggest a possible sensitivity to conflict detection, which is one of the functions ascribed to the supplementary motor area87,88,89. Notably, a network involving the SMA, the frontal gyrus and the IPS has been shown to be jointly activated by the processing of both temporal and spatial information, suggesting that these regions may constitute a common magnitude representation system allowing the integration of time and space in service of action90. Present findings that these regions appear to support a spatialized representation of the temporal organization of EAMs along a sagittal mental line are thus consistent with the proposal that such an organization may arise from sensorimotor experience related to walking in the physical space91,92.

Finally, here we further assessed context-dependent interactions supporting mental projection along EAMs, using psychophysiological interaction analysis. Results showed that the connectivity between a set of regions was overall increased for near as compared with far EAMs (see Table 3). In detail, the HC, LG and FG all showed higher functional coupling with parietal regions (AG and IPS). The left cerebellum was also more strongly coupled with parietal regions, the visual cortex and the HC, in the case of near EAMs. These findings are overall consistent both with evidence for shared mechanisms between processing of self-related events in the past and in the future4, and with that for shared phenomenological features between past and personal future events according to their temporal distance10. Both past and future episodic autobiographical events closer in time to the present moment contain more sensory details and yield to a stronger feeling of re-experiencing/pre-experiencing10. Our results suggest that this effect may be at least partially supported by specific context-dependent interactions between regions of the early visual cortex (LG, FG), the HC, and multimodal parietal regions (IPS, AG). Moreover, the activity of the former regions could be more strongly modulated by the cerebellum during near compared with far EAMs. The posterior cerebellum is functionally connected to different regions of the Autobiographical Memory (AM) network; Crus 1, which corresponds to the location highlighted in the present study, is coactivated with the medial temporal lobes, as well as with the early visual cortex and the parietal cortex during the retrieval of AMs, and it has been proposed to contribute to sequencing aspects of AMs93. Task-dependent connectivity between the HC and the lateral parietal cortex has also been observed in previous studies. Using intracranial electroencephalography, Das and Menod94 recently showed causal interactions between the HC and the AG during episodic memory recall. Task-dependent connectivity between the HC and posterior parietal regions has been further observed during EAM, with hippocampal connectivity with the AG being positively modulated during successful retrieval95. Finally, activation of the lingual and fusiform gyrus has been previously linked to autobiographical memory re-experiencing96, whereas lateral parietal regions such as the AG have been proposed to play a role in the mental construction of perceptually rich images and the representation of temporal contextual information97,98. One possibility is that increased functional coupling between these regions during the near condition may reflect the increased feeling of re-experiencing/pre-experiencing and the stronger presence of sensory detail, which are typically associated with events closer to the present time10. It is important, however, to point out that the degree of re-experiencing was not explicitly assessed in the present study. The AG is further activated by episodic spatial navigation tasks performed using an egocentric perspective18. Moreover, this region has been widely implicated in semantic cognition99, and, more recently, has been shown to be involved in supporting personal semantic information, including autobiographical facts and repeated events100. A further possibility is thus that the AG may be involved in supporting spatialized mental travel along the timeline of autobiographical knowledge. However, future studies are needed to directly test these possibilities.

In conclusion, although many studies investigated the cognitive processes involved in ordering past and future events in time, the neural network underlying these processes remains to be fully specified. In the current study we used a spatiotemporal interference task to unveil the brain areas involved in mental projection through EAMs. We observed that, although a distributed network of cortical and subcortical regions is implicated in mental projection across past and future independently from the memory category (personal - EAM or public - PE), a series of brain regions exhibit a neural modulation as a function of the time period, and a subset of them also as a function of the compatibility along the mental timeline, but selectively for EAM, indicating a role of these regions in the temporal sequencing of personal but not public events. Future studies are needed to further investigate, for example by using multivoxel pattern classification analyses, how temporal attributes of autobiographical memories are coded within brain regions supporting EAM and, whether these representations possibly undergo a dynamic remapping as time passes after the event.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the OSF repository, https://osf.io/fahzm/.

References

Tulving, E. Memory and consciousness. Can. Psychol. 26, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080017 (1985).

D’Argembeau, A. Zooming in and out on one’s life: autobiographical representations at multiple time scales. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 2037–2055. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01556 (2020).

Conway, M. A. & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychol. Rev. 107, 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.107.2.261 (2000).

Benoit, R. G. & Schacter, D. L. Specifying the core network supporting episodic simulation and episodic memory by activation likelihood Estimation. Neuropsychologia. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.034 (2015).

Busby, J. & Suddendorf, T. Recalling yesterday and predicting tomorrow. Cogn. Dev. 20, 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2005.05.002 (2005).

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T. & Schacter, D. L. Age-related changes in the episodic simulation of future events. Psychol. Sci. 19, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02043.x (2008).

Squire, L. R. et al. Role of the hippocampus in remembering the past and imagining the future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 19044–19048. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1014391107 (2010).

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D. & Maguire, E. A. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 1726–1731 (2007).

Race, E., Keane, M. M. & Verfaellie, M. Medial Temporal lobe damage causes deficits in episodic memory and episodic future thinking not attributable to deficits in narrative construction. J. Neurosci. 31, 10262–10269 (2011).

D’Argembeau, A. & Van der Linden, M. Phenomenal characteristics associated with projecting oneself back into the past and forward into the future: influence of Valence and Temporal distance. Conscious Cogn. 13, 844–858 (2004).

Stillman, P. E., Lee, H., Deng, X., Unnava, H. R. & Cunningham, W. A. Fujita K. Neurological evidence for the role of construal level in future-directed thought. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 12, 937–947 (2017).

Colás-Blanco, I., Mioche, J., La Corte, V. & Piolino, P. The role of Temporal distance of the events on the Spatiotemporal dynamics of mental time travel to one’s personal past and future. Sci. Rep. 12, 2378 (2022).

Santangelo, V. et al. Enhanced brain activity associated with memory access in highly superior autobiographical memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, 7795–7800. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1802730115 (2018).

Orwig, W. et al. Cortical hubs of highly superior autobiographical memory. Cortex 179, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2024.06.018 (2024).

Santangelo, V., Pedale, T., Macrì, S. & Campolongo, P. Enhanced cortical specialization to distinguish older and newer memories in highly superior autobiographical memory. Cortex 129, 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.04.029 (2020).

D’Argembeau, A., Jeunehomme, O., Majerus, S., Bastin, C. & Salmon, E. The neural basis of Temporal order processing in past and future thought. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 27, 185–197 (2015).

Ciaramelli, E., Anelli, F. & Frassinetti, F. An asymmetry in past and future mental time travel following VmPFC damage. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 16, 315–325 (2021).

Teghil, A., Marc, I. B. & Boccia, M. Mental representation of autobiographical memories along the sagittal mental timeline: evidence from Spatiotemporal interference. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 28, 1327–1335. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01906-z (2021).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 41, 1149–1160. (2009).

Indovina, I. et al. Path integration in 3D from visual motion cues: A human fMRI study. Neuroimage 142, 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.07.008 (2016).

Nemmi, F. et al. Landmark sequencing and route knowledge: an fMRI study. Cortex 49, 507–519 (2013).

Ino, T., Nakai, R., Azuma, T., Kimura, T. & Fukuyama, H. Brain activation during autobiographical memory retrieval with special reference to default mode network. Open. Neuroimag. J. 5, 14–23 (2011).

Teghil, A., Bonavita, A., Procida, F., Giove, F. & Boccia, M. Temporal organization of episodic and Experience-near semantic autobiographical memories: neural correlates and Context-dependent connectivity. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 34, 2256–2274. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01906 (2022).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 (1971).

Dritschel, B. H., Williams, J. M. G., Baddeley, A. D. & Nimmo-Smith, I. Autobiographical fluency: A method for the study of personal memory. Mem. Cognit. 20, 133–140 (1992).

Conti, M., Teghil, A. & Boccia, M. The autobiographical fluency task: validity and reliability of a tool to assess episodic autobiographical memory and experience-near personal semantics. J. Neuropsychol. 18, 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnp.12351 (2024).

Boccia, M., Teghil, A. & Guariglia, C. Looking into recent and remote past: Meta-analytic evidence for cortical re-organization of episodic autobiographical memories. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 107, 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.003 (2019).

Moeller, S. et al. Multiband multislice GE-EPI at 7 Tesla, with 16-fold acceleration using partial parallel imaging with application to high Spatial and Temporal whole-brain fMRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 63, 1144–1153. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22361 (2010).

Xu, J. et al. Evaluation of slice accelerations using multiband echo planar imaging at 3 T. Neuroimage 83, 991–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.055 (2013).

Feinberg, D. A. et al. Multiplexed echo planar imaging for sub-second whole brain fMRI and fast diffusion imaging. PLoS One. 5, e15710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015710 (2010).

Tisdall, M. D. et al. Volumetric navigators for prospective motion correction and selective reacquisition in neuroanatomical MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 68, 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.23228 (2012).

Hess, A. T., Tisdall, M. D., Andronesi, O. C., Meintjes, E. M. & van der Kouwe, A. J. Real-time motion and B0 corrected single voxel spectroscopy using volumetric navigators. Magn. Reson. Med. 66, 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22805 (2011).

Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods. 16, 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0235-4 (2018).

Gorgolewski et al. A flexible, lightweight and extensible neuroimaging data processing framework in python. Front. Neuroinf. 5, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2011 (2011). Nipype.

Tustison, N. J. et al. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 29, 1310–1320. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908 (2010).

Zhang, Y., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 20, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1109/42.906424 (2001).

Dale, A. M., Fischl, B. & Sereno, M. I. Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 9, 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.1998.0395 (1999).

Klein, A. et al. Mind-boggling morphometry of human brains. PLoS Comp. Biol. 13, e1005350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005350 (2017).

Power, J. D. et al. Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. NeuroImage 84, 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.048 (2014).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2, 125–141 (2012).

Nieto-Castanon, A. & Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. CONN functional connectivity toolbox: RRID SCR_009550, release 22. https://doi.org/10.56441/hilbertpress.2246.5840 (2022).

Penny, W. D., Friston, K. J., Ashburner, J. T., Kiebel, S. J. & Nichols, T. E. (eds) Statistical Parametric Mapping: the Analysis of Functional Brain Images (Elsevier, 2011).

Nieto-Castanon, A. FMRI denoising pipeline. In Handbook of Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods in CONN (17–25). Hilbert. (2020).

Hallquist, M. N., Hwang, K. & Luna, B. The nuisance of nuisance regression: spectral misspecification in a common approach to resting-state fMRI preprocessing reintroduces noise and obscures functional connectivity. Neuroimage 82, 208–225 (2013).

Behzadi, Y., Restom, K., Liau, J. & Liu, T. T. A component-based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion-based fMRI. Neuroimage 37, 90–101 (2007).

Chai, X. J., Nieto-Castanon, A., Ongur, D. & Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. Anticorrelations in resting state networks without global signal regression. Neuroimage 59, 1420–1428 (2012).

Friston, K. J. et al. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage 6, 218–229 (1997).

McLaren, D. G., Ries, M. L., Xu, G. & Johnson, S. C. A generalized form of context-dependent Psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): a comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage 61, 1277–1286 (2012).

Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061 (2009).

Laurencelle, L. & Cousineau, D. Analysis of proportions using Arcsine transform with any experimental design. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1045436 (2023).

Talairach, J. & Tournoux, P. Co-planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. (Thieme, 1988).

Schacter, D. L. et al. The future of memory: remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron 76, 677–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.001 (2012).

Teghil, A., Bonavita, A., Guariglia, C. & Boccia, M. Commonalities and specificities between environmental navigation and autobiographical memory: A synthesis and a theoretical perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 127, 928–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev34102149 (2021).

Daviddi, S., Pedale, T., Jacques, S., Schacter, P. L., Santangelo, V. & D.L. & Common and distinct correlates of construction and elaboration of episodic-autobiographical memory: an ALE meta-analysis. Cortex 163, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2023.03.005 (2023).

Conway, M. A., Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. & Whitecross, S. E. The neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: A slow cortical potential study of autobiographical memory retrieval. J. Mem. Lang. 45, 493–524 (2001).

Viard, A. et al. Mental time travel into the past and the future in healthy aged adults: an fMRI study. Brain Cogn. 75, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2010.10.009 (2011).

Daselaar, S. M. et al. The Spatiotemporal dynamics of autobiographical memory: neural correlates of recall, emotional intensity, and reliving. Cereb. Cortex. 18, 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhm048 (2008).

Cabeza et al. Brain activity during episodic retrieval of autobiographical and laboratory events: an fMRI study using a novel photo paradigm. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16, 1583–1594. https://doi.org/10.1162/0898929042568578 (2004).

Cabeza, R. & Jacques, S. Functional neuroimaging of autobiographical memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.02.005 (2007).

Pearson, J. The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0202-9PMID-31384033 (2019).

Kosslyn, S. M. & Thompson, W. L. When is early visual cortex activated during visual mental imagery? Psychol. Bull. 129, 723–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.723 (2003).

Eichenbaum, H., Sauvage, M., Fortin, N., Komorowski, R. & Lipton, P. Towards a functional organization of episodic memory in the medial Temporal lobe. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1597–1608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.07.006 (2012).

Hassabis, D. & Maguire, E. A. Deconstructing episodic memory with construction. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 299–306 (2007).

Hassabis, D. & Maguire, E. A. The construction system of the brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 364, 1263–1271 (2009).

Maguire, E. A. & Mullaly, S. L. The hippocampus: a manifesto for change. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142, 1180–1189. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033650 (2013).

Julian, J. B., Keinath, A. T., Marchette, S. A. & Epstein, R. A. The neurocognitive basis of Spatial reorientation. Curr. Biol. 28, R1059–R1073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.057 (2018).

Vann, S. D., Aggleton, J. P. & Maguire, E. A. What does the retrosplenial cortex do? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 792–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2733 (2009).

Sherrill, K. R. et al. Hippocampus and retrosplenial cortex combine path integration signals for successful navigation. J. Neurosci. 33, 19304–19313 (2013).

Auger, S. D., Zeidman, P. & Maguire, E. A. A central role for the retrosplenial cortex in de Novo environmental learning. Elife 4, e09031. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.09031 (2015).

Aminoff, E., Gronau, N. & Bar, M. The parahippocampal cortex mediates Spatial and nonspatial associations. Cereb. Cortex. 17, 1493–1503. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhl078 (2007).

Bar, M., Aminoff, E. & Schacter, D. L. Scenes unseen: the parahippocampal cortex intrinsically subserves contextual associations, not scenes or places per se. J. Neurosci. 28, 8539–8544. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0987-08.2008 (2008).

Pudhiyidath, A. et al. Representations of Temporal community structure in hippocampus and precuneus predict inductive reasoning decisions. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 34, 1736–1760 (2021).

Alexander, A. S., Place, R., Starrett, M. J., Chrastil, E. R. & Nitz, D. A. Rethinking retrosplenial cortex: perspectives and predictions. Neuron 111, 150–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2022.11.006 (2023).

Terada, S., Sakurai, Y., Nakahara, H. & Fujisawa, S. Temporal and rate coding for discrete event sequences in the hippocampus. Neuron 94, 1248–1262e4 (2017).

Hirono, N. et al. Hypofunction in the posterior cingulate gyrus correlates with disorientation for time and place in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 64, 552–554 (1998).

Sherrill, K. R. et al. Generalization of cognitive maps across space and time. Cereb. Cortex. 8, 7971–7992. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhad092 (2023).

Zeidman, P. & Maguire, E. A. Anterior hippocampus: the anatomy of perception, imagination and episodic memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 173–182 (2016).

Stachenfeld, K. L., Botvinick, M. M. & Gershman, S. J. The hippocampus as a predictive map. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1643–1653 (2017).

Behrens, T. E. J. et al. Kurth-Nelson, Z. What is a cognitive map? Organizing knowledge for flexible behavior. Neuron 100, 490–509 (2018).

MacDonald, C. J., Lepage, K. Q., Eden, U. T. & Eichenbaum, H. Hippocampal time cells Bridge the gap in memory for discontiguous events. Neuron 71, 737–749 (2011).

Sugar, J. & Moser, M. B. Episodic memory: neuronal codes for what, where, and when. Hippocampus 12, 1190–1205. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.23132 (2019).

Hodges, S., Berry, E. & Wood, K. SenseCam: a wearable camera that stimulates and rehabilitates autobiographical memory. Memory 19, 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.605591 (2011).

Milton, F. et al. An fMRI study of long-term everyday memory using SenseCam. Memory 19, 733 – 44 .https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.552185 (2011).

Nielson, D. M., Smith, T. A., Sreekumar, V., Dennis, S. & Sederberg, P. B. Human hippocampus represents space and time during retrieval of real-world memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 11078–11083. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1507104112 (2015).

Arzy, S., Collette, S., Ionta, S., Fornari, E. & Blanke, O. Subjective mental time: the functional architecture of projecting the self to past and future. Eur. J. Neurosci. 30, 2009–2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06974.x (2009).

Garavan, H., Ross, T., Kaufman, J. & Stein, E. A midline dissociation between error-processing and response-conflict monitoring. Neuroimage 20, 1132–1139 (2003).

Nachev, P., Rees, G., Parton, A., Kennard, C. & Husain, M. Volition and conflict in human medial frontal cortex. Curr. Biol. 15, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.006 (2005).

Ullsperger, M. & von Cramon, D. Y. Subprocesses of performance monitoring: a dissociation of error processing and response competition revealed by event-related fMRI and erps. Neuroimage 14, 1387–1401 (2001).

Cona, G., Wiener, M. & Scarpazza, C. From ATOM to GradiATOM: cortical gradients support time and space processing as revealed by a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. NeuroImage 224, 117407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117407 (2021).

Miles, L. K., Nind, L. K. & Macrae, C. N. Moving through time. Psychol. Sci. 21, 222e223 (2010).

Rinaldi, L., Locati, F., Parolin, L., Bernardi, N. F. & Girelli, L. Walking on a mental timeline: Temporal processing affects step movements along the sagittal space. Cortex 78, 170–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2016.02.013 (2016).

Addis, D. R., Moloney, E. E., Tippett, L. J., Roberts, P. R. & Hach, S. Characterizing cerebellar activity during autobiographical memory retrieval: ALE and functional connectivity investigations. Neuropsychologia 90, 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.05.025 (2016).

Das, A. & Menon, V. Frequency-specific directed connectivity between the hippocampus and parietal cortex during verbal and Spatial episodic memory: an intracranial EEG replication. Cereb. Cortex. 34, bhae287. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhae287 (2024).

Nawa, N. E. & Ando, H. Effective connectivity during autobiographical memory search. Brain Behav. 10, e01719. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1719 (2020).

Gilboa, A., Winocur, G., Grady, C. L., Hevenor, S. J. & Moscovitch, M. Remembering our past: functional neuroanatomy of recollection of recent and very remote personal events. Cereb. Cortex. 14, 1214e1225. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh082 (2004).

Ramanan, S., Piguet, O. & Irish, M. Rethinking the role of the angular gyrus in remembering the past and imagining the future: the contextual integration model. Neurosci. Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatry. 24, 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858417735514 (2018).

Moscovitch, M., Cabeza, R., Winocur, G. & Nadel, L. Episodic memory and beyond: the hippocampus and neocortex in transformation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 105–134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143733 (2016).

Kuhnke, P. et al. The role of the angular gyrus in semantic cognition: a synthesis of five functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Struct. Funct. 228 (1), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-022-02493-y (2023).

Tanguay, A. F. N. et al. The shared and unique neural correlates of personal semantic, general semantic, and episodic memory. eLife 12, e83645. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.83645 (2023).

Funding

This study has been funded by the European Union (ERC, ATENA, 101039206). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. designed the study, supervised the project, and obtained the funding from the European Research Council (ATENA/101039206). V.S. and A.T. collected the data. G.C. supervised the MRI acquisitions and provided reports on the imaging data. I.R. recruited volunteers. V.S., A.T., M.B. and F.G. performed the statistical analyses. V.S. and A.T. drafted the manuscript with substantial input from all authors. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sulpizio, V., Teghil, A., Ruffo, I. et al. Unveiling the neural network involved in mentally projecting the self through episodic autobiographical memories. Sci Rep 15, 12781 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97515-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97515-0