Abstract

The present research outlines a procedure for the treatment of municipal wastewater by utilizing reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4 (rGO@Fe3O4) magnetic nanocomposites to effectively remove hexavalent chromium through adsorption process. rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites were synthesized through a conventional procedure and applied for Cr (VI) removal from wastewater. The nanocomposites were characterized using techniques including Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, X-Ray Diffraction Analysis, Scanning Electron Microscopy, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area analysis, and Raman spectroscopy. The batch adsorption process was optimized by conducting response surface methods for assessing primary variables affecting the adsorption process. Adsorption equilibrium mechanism was analyzed through the application of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models, utilizing both linear and nonlinear regression approaches. Furthermore, multiple error functions were employed to assess the validity of models. Results revealed that adsorption mechanism exhibited heterogeneous adsorption, aligning well with the Freundlich isotherm model, which accurately corresponded to experimental data. Moreover, the sorption kinetics were well described by the pseudo-second order kinetic model. The results obtained indicated that adsorption of Cr(VI) onto surface of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites is affected by multi-site interactions. The correlation between experimental data and isotherm models further supports the suitability of this material in environmental remediation, offering a promising approach for sustainable wastewater treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wastewater pollution has become a significant environmental issue, necessitating the development of innovative and effective treatment techniques to minimize detrimental effects on ecosystems and human health. Heavy metals are among the most concerning contaminants found in wastewater. These inorganic pollutants are particularly hazardous due to their persistence, toxicity, and tendency to accumulate in aquatic environments1. Chromium is a heavy metal commonly found in wastewater because of industrial activities such as electroplating, metal finishing, textile production, chromate preparation, and fertilizer manufacturing. It exists in various oxidation states, with trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) and hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) being the most stable and frequently encountered forms in the environment2. Cr(III) is notably non-toxic and an essential trace element in human nutrition. In contrast, Cr(VI) occurs in water as oxyanions such as chromate (CrO₄2⁻), hydrogen chromate (HCrO₄⁻), and dichromate (Cr₂O₇2⁻) which are highly toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic. The presence of Cr(VI) in water at elevated concentrations poses a major environmental and health concern. Therefore, the removal of chromium from polluted aquatic environments or the conversion of these ions to the non-toxic trivalent form is of critical significance3,4

Several feasible methods for chromium removal from industrial wastewater and natural aquatic sources are known, including chemical reduction5,6, bioremediation7, ion exchange8, adsorption9, membrane filtration10 and electrocoagulation11. Chemical reduction followed by precipitation currently constitutes the majority of employed techniques in both industry and literature for the removal of Cr(VI) among the mentioned approaches12 However, the oxy-anion forms of hexavalent chromium, primarily chromate (CrO₄2⁻) and dichromate (Cr₂O₇2⁻), do not precipitate efficiently in aquatic environments using standard precipitation methods13,14. This approach has notable limitations including the requirement for reducing agents and challenges in scaling up for large-scale industrial wastewater facilities. Additionally, the composition of the effluent significantly influences the efficiency of precipitation; both organic and inorganic contaminants can reduce the effectiveness of heavy metal removal15,16. Bioremediation is an environmentally friendly process; however, it is often limited by slow reaction rates and ineffective Cr(VI) degradation at high concentrations17,18. The ion exchange is constrained by the need for chemical reagents for resin regeneration, the generation of large volumes of backwashing water, and high operational costs19. While membrane filtration is effective, it is prone to fouling issues and requires frequent maintenance. Similarly, electrocoagulation also faces fouling challenges, and, in addition, its high energy consumption further limits its practical application20. Each technique has unique advantages and drawbacks, depending on the specific application and pollutant concentration. However, many of these methods are either inadequate or expensive when Cr(VI) is present in relatively small quantities.

Adsorption technology has been extensively utilized for the removal of chromium from industrial wastewater, and over time, it has proven to be one of the most promising strategies. Various adsorbents have demonstrated high efficiency in chromium removal under optimized conditions21. This method is often preferred due to its simplicity, high efficiency, and the selectivity offered by the functional groups present on the surface of the adsorbent material22. Additionally, adsorbent materials can be structurally modified to target specific pollutants, enable pollutant recovery, and allow for multiple reuse cycles. The adsorption process involves the interaction between adsorbates and adsorbents in liquid media, typically occurring through physical or chemical mechanisms23,24.

Graphene oxide (GO), produced by oxidizing low-cost graphite-based materials, is a highly promising nanomaterial widely used for removing both anionic and cationic pollutants, especially heavy metals due to its versatile adsorption mechanisms25. GO has attracted significant attention due to its unique layered structure and abundant functional groups, such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, making it an ideal candidate for developing advanced adsorbents for pollutant removal26,27. Chemical modifications of graphene and graphene oxide can improve their solubility in water and impart surface characteristics that enhance their ability to disperse in aqueous solutions and adsorb pollutants. The use of modified GO magnetic nanoparticles (GO-MNs) in adsorption processes has shown considerable advantages. Magnetic nanomaterials can selectively adsorb targeted pollutants, providing high adsorption capacity for efficient removal. They can be easily separated from the aqueous solution using an external magnetic field, eliminating the need for additional equipment. Additionally, they are reusable, making the process both cost-effective and environmentally friendly28.

This study presents a unique approach by utilizing linear and nonlinear kinetic and isotherm models using rGO-Fe3O4 nanocomposites for the removal of chromium from wastewater through adsorption. Batch adsorption experiments were conducted to assess the capacity of the nanocomposites for chromium removal under various conditions. Equilibrium studies were performed to analyze the adsorption behavior, with the experimental data fitted to the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms using both linear and nonlinear regression models. Kinetic studies were also conducted to evaluate the adsorption rate of chromium onto the rGO-Fe₃O₄ nanocomposites. The experimental data were analyzed using the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models to determine the adsorption kinetics. These models were employed to determine the adsorption capacity and the nature of the adsorption process, providing insights into the efficiency and mechanism of chromium removal by rGO-Fe3O4 nanocomposites.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, standards, samples

The stock solution of chromium used throughout the experiments was prepared from potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) salt purchased from Riedel-de-Haën (Germany). All solutions were prepared with deionized water supplied from an Elga Flex 3 Water Purification System (High Wycombe, England), providing a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ.cm. Chemicals obtained from Merck included potassium permanganate (KMnO4), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 35%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95–98%), ammonia solution (NH4OH, 25%), iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO₄·7H₂O), sodium chloride (NaCl) and hydrazinium hydroxide (N2H4·H2O). High-purity (99.99%) graphite powder was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals utilized were of analytical grade and applied without any further preparation. This study examined the isothermal and kinetic characteristics of chromium adsorption onto rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites, utilizing municipal wastewater collected from a wastewater treatment plant in İstanbul, Türkiye.

Synthesis of rGO-Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposites

GO was synthesized from graphite powder using the method described by Hummers29. In this procedure, 2.0 g of graphite and 46.0 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid were added to a flask, and the mixture was stirred for 1.0 h using a magnetic stirrer. Then, 6.0 g of potassium permanganate was gradually introduced into the mixture while maintaining the reaction temperature below 20 °C with an ice bath. The mixture was heated to 35 °C and stirred continuously for 2.0 h. Afterward, 92 mL of deionized water was added, and the mixture was stirred for an hour before 280 mL of deionized water was added. The reaction was completed by adding 10.0 mL of hydrogen peroxide, which resulted in a color change from deep brown to yellow. The suspension was left to settle overnight, and the supernatant was removed by decantation. The GO powder was repeatedly washed with hydrochloric acid (5.0%, v/v), acetone, and distilled water, then dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C for 24 h.

The rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites were synthesized through a chemical coprecipitation methodology30. In the first step, 250 mg of GO was evenly distributed in 250 mL of distilled water and subjected to ultrasonication for a period of 1.0 h. A solution with the following composition was prepared by dissolving 8.109 g of FeCl3·6H2O and 4.17 g of FeSO4·7H2O in 50 mL of ultrapure water, ensuring a 2:1 molar ratio of Fe3+ to Fe2+. The solution was incorporated into the GO suspension and subsequently heating to 80 °C. Gradually, 30.0 mL of ammonia solution was slowly introduced to the mixture to facilitate the precipitation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Following a controlled temperature increase to 90 °C, 250 μL of hydrazine was added to promote reduction of GO. The mixture was agitated for an additional 4.0 h at a temperature of 90 °C within a nitrogen-laden environment. The black precipitates were separated from the mixture employing a neodymium magnet and were then thoroughly washed several times with distilled water and ethanol. Finally, the rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites underwent a drying process at 80 °C for a duration of 24 h.

Determination of point of zero charge

The solid addition method was used to determine the point of zero charge (pHPZC) of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites31. For this, a set of conical flasks containing 25 mL of 0.1 M KNO3 were prepared. The initial pH (pH0) of these solutions was adjusted across a range from 2 to 12 using 0.1 N HCl or NaOH. Each solution received 50 mg of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites and left to reach equilibrium at room temperature for 24 h. After this period, the final pH (pHf) was measured and pHPZC was determined by plotting the difference between the initial and final pH (ΔpH) values against initial pH.

Instrumentation

The rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites were characterized using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images. FTIR spectra were obtained using a Bruker Tensor 27 model Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) spectrometer with a wavenumber precision of ± 0.01 cm−1, recorded over the range of 500–4000 cm−1. Crystal structure analysis was conducted utilizing a PANanalytical X’Pert Pro XRD instrument equipped with a Cu-Kα radiation source, scanning the 2θ angle from 10° to 90°, at a rate of 2°/min, with a current of 40 mA and a voltage of 45 kV. The specific surface area of the materials was analyzed using a Quantachrome Quadrosorb SI BET instrument after degassing at 393 K for 2 h. The Zeiss EVO LS10 type scanning electron microscope was utilized to capture SEM pictures in beam mode at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. The nanocomposites were coated with gold–palladium under argon plasma employing a Quorum SC7620 Sputter Coater. FESEM and EDS analyses were conducted using a Thermo Scientifıc Apreo 2 S LoVac scanning electron microscope.

Box-Behnken experimental design

The influence of experimental variables on the adsorption capacity of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites was examined employing response surface methodology. A Box-Behnken design (BBD) was utilized to optimize three variables: agitation period, initial concentration of the pollutant, and adsorbent amount. The experimental data, derived from the mean values of three replicates, was assessed through Design Expert software (trial version 13, Stat-ease).

The BBD experiment involved three factors and three levels (− 1, 0, and + 1) for the input variables: rGO@Fe3O4 amount (50–150 mg), agitation duration (10–40 min), and initial chromium ion concentration (15–35 mg/L), as given in Table 1. The design covered 17 tests, each with 5 repetitions at the center point. The response value for each instance was calculated by determining the average of the results for triplicates. The equation presented below describes the system’s behavior32.

The equation comprises the following variables: y symbolizes the response (dependent variable), ε indicates the residual associated with the experiments or random error, \({\beta }_{0}\), \({\beta }_{i}\) and \({\beta }_{ij}\) describe the constant term, the linear effect, and the coefficient of the interaction parameters, respectively32.

The adequacy and significance of the model were assessed utilizing an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test. The adequateness of the predictive equation was assessed through R-squared values, comprising the coefficient of determination (R2) and the adjusted-R2. Any probability values (p-value) that were less than 0.05 were statistically significant.

Adsorption experiments on wastewater

The removal of chromium ions utilizing rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites was performed in batch mode experiments on municipal wastewater effluent. The chromium concentrations in influent and effluent samples were determined using a flame atomic absorption spectrometer (FAAS; ATI UNICAM 929 AA, UNICAM, England). The instrument was equipped with a burner head and a chromium hollow cathode lamp (PHOTRON) operated at a current of 10 mA. The lamp had a spectral bandwidth of 0.50 nm, with an analytical wavelength set at 357.9 nm. For background correction, a deuterium lamp was included. Atomization was achieved by creating a stoichiometric flame using an acetylene/air mixture.

Adsorption process involved batch adsorption experiments, followed by the magnetic separation of nanocomposite and the determination of residual Cr(VI) concentration in the effluent using FAAS system. The adsorption capacity and removal efficiency were calculated based on the Cr(VI) concentrations in influent and effluent. Finally, error analysis was performed to identify the most suitable kinetic and isotherm models describing the adsorption process. In batch experiments, 150 mg of rGO@Fe3O4 was added to 30 mL of Cr(VI) solution in Erlenmeyer flasks. The flasks were agitated at room temperature at a speed of 250 rpm using a mechanical shaker until equilibrium was reached. Following equilibration, the treated solution was separated from the nanocomposite using a neodymium magnet. The residual concentration of Cr (VI) in the solution was quantified by FAAS, with the aid of a pre-constructed calibration plot. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the average results were used for data analysis. The removal efficiency and adsorption capacity of rGO@Fe3O4 for Cr (VI) were determined using the following equations.

qe: equilibrium adsorption quantity, (mg/g).

Ci: initial concentration of Cr(VI) in the samples, (mg/L).

C0: initial concentration of Cr(VI) in the samples prior to treatment, (mg/L).

V: volume of the sample or standard solution of Cr(VI), (L).

m: mass of the rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposite, (g).

%RE: the percentage of Cr (VI) pollution removed from the solution.

Error analysis has been performed to identify the kinetic and isotherm models that best describe the interaction between rGO@Fe3O4 composites and Cr(VI) ions in solution. HYBRID, Chi-square (R2), Average Relative Error (ARE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) statistical measures have been used to assess the reliability of model fit, stated as follows:

where qi,exp and qi,calc represent the experimentally observed and model-predicted adsorption capacities, respectively. n is the number of data points, and p is the number of model parameters. qi,exp was obtained from the experimental runs using Eq. (2), while qi,calc was calculated from non-linear model equations by applying the model parameters derived from both linear and non-linear regressions.

Results and discussions

rGO@Fe3O4 characterization

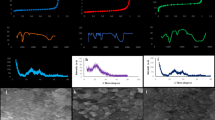

FTIR method was employed to confirm the synthesis of GO and rGO@Fe3O4, as well as to identify functional groups and metal oxide bonds. As shown in Fig. 1a, a prominent C–O band at 1039 cm−1 and C = O interactions at 1723 cm−1 indicate the formation of carbon–oxygen bonds and the successful formation of GO. Additionally, a broad band at 3354 cm−1 signifies the presence of -OH bonds in the structure, which may also suggest moisture-absorbing properties of the synthesized material33.

The spectra of Fe3O4 and rGO@Fe3O4 are illustrated in Fig. 1b and c, respectively. The spectrum of rGO@Fe3O4 reveals significant differences compared to GO, primarily the absence of peaks at 1723 cm−1 and 1039 cm−1. This is attributed to the partial removal of oxygen-containing groups during the in-situ reduction of GO by hydrazine. A prominent broad band around 3380 cm−1 indicates the presence of hydrogen bonding, while the peak at 1637 cm−1 corresponds to the altered C = O stretching vibrations due to the formation of –COO– groups during the iron oxide coating procedure. Additionally, the sharp band at 549 cm−1 confirms the formation of Fe–O bonds, validating the successful synthesis of rGO@Fe3O434,35. The presence of both –OH groups and Fe–O/Fe–OH bonds in the nanocomposite structure highlights its multifunctionality, facilitating adsorption processes such as reduction, electrostatic attraction, co-precipitation, ligand exchange, and chelation, which collectively contribute to its potential removal mechanisms30,36,37.

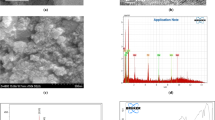

SEM analysis was performed to examine the surface morphology of GO and rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites. Figure 2 illustrates the structure of GO and rGO@Fe3O4 as captured by SEM. As shown in Fig. 2a and b, GO particles exhibit an irregular and non-uniform surface. The particles appear to be clumped together in some regions. On the other hand, Fig. 2c shows the morphology of rGO@Fe3O4, exhibiting a diverse range of particle sizes.

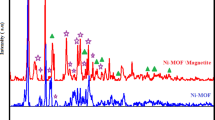

The crystal structure and phase composition of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites were identified through XRD analysis rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites were identified through XRD analysis. Figure 3 illustrates the XRD patterns of Fe3O4 and the synthesized rGO@Fe3O4. The distinct peak patterns in diffraction for the face-centered cubic configuration of Fe3O4 at 2θ values of 30.4°, 35.7°, 43.2°, 54.0°, 57.2° and 63.0° were ascribed to patterns that correspond to reflections from the (220), (311), (400), (422), (511) and (440) planes, respectively (JCPDS Card No. 75–0033). The diffraction pattern of the rGO-Fe₃O₄ composite resembles that of Fe₃O₄, with the exception of a slightly broader peak near 26.0°, which is indicative of the reduction of GO and the formation of rGO38.

The crystallite size (D) of 43.62 nm was calculated using the Scherrer’s equation and Modified Scherrer’s equation 39,40:

where \(\beta\) is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) expressed in radians, K is the Scherrer constant (K = 0.89), λ is the wavelength.

The predicted crystallite size attained corresponds with the SEM pictures, indicating the efficient formation of the nanomaterial and the phase morphologies.

Figure 4 shows the Raman spectra of GO and rGO-Fe₃O₄ composite. In the Raman spectrum of GO, the prominent peaks at 1361 cm−1 (D band) and 1596 cm−1 (G band) correspond to the vibrations of sp2 carbon atoms in the 2D hexagonal lattice of graphitic sheets and sp3 carbon atoms associated with disorders and defects, respectively. The relative intensity of the D band compared to the G band provides a qualitative measure of the degree of lattice defects in carbonaceous materials, with the intensity ratio of the D band to the G band (ID/IG) commonly used to characterize the level of defects in the graphene structure. From the Raman spectra, ID/IG ratio increased from 0.94 to 1.38, which is attributed to the reduction of GO, resulting in a smaller average size of the sp241. Additionally, a 7 cm−1 downshift was observed in the G band in rGO-Fe₃O₄, confirming charge transfer between the two materials. This shift indicates a strong interaction between the rGO and Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles42.

The specific surface area of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites was calculated utilizing BET isotherm modeling. The BET surface area of graphene oxide was measured as 1.073 m2/g, while the synthesized rGO@Fe3O4 exhibited a significantly increased surface area of 31.124 m2/g, contributing to its enhanced adsorption capacity for pollutants. This increase in surface area can likely be attributed to the coprecipitation method used in coating magnetic nanoparticles with graphene oxide.

Effect of adsorption parameters

Effect of pH

One of the key variables influencing the removal strategy and adsorption kinetics in adsorption-based Cr(VI) removal experiments is the medium’s pH43. Both Cr(VI) and Cr(III) can exist in various forms within the natural environment and in water matrices whose pH value varies between 2.0 and 10. When the pH is below 4.0, Cr(III) is inclined to establish hexacoordinate complexes with various complexing agents. In the pH range of 4.0–6.0, Cr(III) is known to produce hydrolysis products44. Cr(VI) primarily exists as the negatively charged species HCrO4⁻ in the pH range of 2.0–6.0. Above pH 6.0, CrO42− and Cr2O7⁻ gradually becomes the dominant species due to deprotonation of HCrO4−45. Figure 5a shows the results of solid addition method to estimate the pHPZC of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites through the relationship between ΔpH and pH0. Figure 5b illustrates the removal procedures for Cr(VI) performed at pH values ranging from 2.5 to 6.0. There was a noticeable decline in treatment efficiency with increasing pH levels. The adsorption of Cr(VI) in a wide pH range may be related to the mechanisms of ion exchange, chelation, reduction, electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding. According to pHPZC value rGO@Fe3O4 (5.7), the surface of rGO@Fe3O4 carries positively charged functional groups in pH < pHPZC, such as protonated carboxyl groups and Fe-containing surface sites, creating strong electrostatic interactions that drive the negatively charged species of Cr(VI) onto the nanocomposite surface. As the pH rises above 4, the removal percentage gradually decreases, likely due to the competition between OH⁻ ions and Cr(VI) species for adsorption sites46. Although pH 2.0 provided slightly higher removal efficiency than pH 4.0 conditions, pH 4.0 was selected to avoid extreme conditions and ensure practical feasibility in wastewater treatment applications.

(a) Point of zero charge of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites and (b) the effect of pH of the medium (n = 3) (The constant parameters used in the medium’s pH value optimization: 8.0 mL sample volume, 30 mg/L of Cr(VI) standard solution, 100 mg adsorbent, 30 min of mechanical shaker mixing, agitation speed 250 rpm).

Results of multi-objective optimization

An experiment utilizing the BBD was carried out to investigate the effects of variables including adsorbent amount, agitation period, and initial concentration of pollutant on adsorption efficacy. Utilizing BBD presents positive aspects in examining response functions among variables while minimizing the number of experimental trials required. By systematically adjusting the key variables and centering on the intermediate levels, quadratic response surfaces can be effectively modeled. The present research involved conducting 17 experiments, during which the removal percentage value was selected as the response to maximize. The BBD table is provided in Table 2. The quadratic equation presented in Eq. (9) shows the relationship between the response and independent variables.

The equation reveals that three experimental parameters—initial concentration of the pollutant (A), contact time (B), and adsorbent dose (C)—significantly influence the response value. The ANOVA table for Cr (VI) removal is presented in Table 3. The ANOVA test indicated that the model was statistically significant, evidenced by a p-value of less than 0.0001. The data obtained and the predicted outcomes of the response demonstrated a significant alignment, as indicated by the model’s determination coefficient (R2) of 0.9953 and an adjusted-R2 value of 0.9916. The high R2 values demonstrate the model’s precision for experimental applications. The lack of fit indicates the model’s inability to effectively elucidate the relationship between variables and the outcome. The most statistically significant factors influencing Cr(VI) removal were the initial concentration (A), contact time (B), adsorbent dose (C), and the interaction between initial concentration and adsorbent dose (AC), all with p-values below 0.05. The quadratic term of the initial concentration (A2) and adsorbent dose (C2) were also significant. However, the interactions between initial concentration and contact time (AB) and between contact time and adsorbent dose (BC) were not statistically significant, as indicated by their higher p-values (> 0.05). The absence of significant lack of fit (p > 0.05) indicated that the model was suitable for the data. Overall, the model demonstrated statistical significance and was appropriate for further examination.

Figure 6 presents three-dimensional response surface plots (3D-RSP) that demonstrate both the primary and interaction effects of independent variables on the dependent variable, represented by the response value. The trend shows that as the initial concentration increases, the removal percentage decreases, indicating a limitation in the adsorption capacity. The color gradient from red to green visually represents the efficiency of the process, with higher efficiencies observed at lower initial concentrations and longer contact times. Increasing the amount of adsorbent results in a higher removal percentage, which demonstrates that more adsorption sites are available for Cr(VI) uptake. A similar trend to the removal percentage is observed for the desirability function, confirming that lower initial concentrations, higher adsorbent doses and sufficient contact time improve overall system performance. The percentage of removal rose from 35.99 to 66.73% as the amount of adsorbent used was increased by three-fold. An increase in the agitation period from 10 to 40 min resulted in an improvement in percentage removal, from 39.25% to 44.52%, for an initial concentration of 35 mg/L Cr(VI). As a result, increasing the quantity of sorbent and extending the agitation period led to improved effectiveness in pollutant removal.

The quadratic model was established based on the desirability function, with the objective of achieving the maximum percent removal result. A variety of combinations produced comparable desirability results, which led to the selection of parameters aimed at maximizing the removal percentage. These parameters include 150 mg of rGO@Fe3O4 sorbent, an agitation period of 40 min, and an initial concentration of 15 mg/L.

Adsorption kinetics

Figure 7 displays the kinetics of sorption for removal of Cr(VI) ions (at a concentration of 10 mg/L) using rGO@Fe3O4 composites. The sorption rate of Cr(VI) on rGO@Fe3O4 composites markedly increased with the duration of batch adsorption, ranging from 5 to 90 min. This indicates that rGO@Fe3O4 composites exhibited a higher adsorption rate as time progressed. During the first 15 min of contact, adsorption occurred rapidly due to the abundance of active sites on the outer layer of rGO@Fe3O4 and abundance of Cr(VI) ions in the solution. After this initial period, the rate decreased as the available active sites became occupied by Cr(VI) ions. The equilibrium time for Cr(VI) adsorption on rGO@Fe3O4 composites was found to be 60 min, suggesting that one hour is sufficient for the removal process. After this period, the rGO@Fe3O4 composites were able to remove approximately 90% of the Cr(VI) from the sample volume.

The kinetics of Cr(VI) adsorption onto rGO@Fe3O4 composites were evaluated adopting PFO and PSO kinetic models. The nonlinear and linear representations of the PFO and PSO kinetic models are defined by Eqs. (10)–(13), respectively. Figure 8 illustrates the plots of both linear and non-linear forms of kinetic models and the relevant kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 4.

The findings indicate that the PFO nonlinear model had the highest correlation coefficient (R2) with a value of 0.9908, in comparison with the obtained value of 0.9474 from the PSO model. Nevertheless, the equilibrium adsorbed amounts, qe values of 8.79 mg/g and 0.398 mg/g derived from the PFO nonlinear and linear models, respectively, contradict both the experimental and calculated values of qe. Furthermore, the linear model of PFO, with its exceptionally high error values, indicates a poor fit to the data. Conversely, the values estimated from the PSO model closely match the experimental data. Figure 8 demonstrates that the nonlinear model better accounts for the complexities of the adsorption process and provides a more accurate and reliable description of the adsorption kinetics, highlighting the limitations of linearization in capturing the true nature of the adsorption process. The statistical characteristics of the PFO model are inadequate compared to those of the PSO. In accordance with the calculated correlation coefficients (R2), statistical findings from both linear and nonlinear modeling, and the results of error analyses, the PSO model can be considered an effective descriptive model for Cr(VI) removal by rGO@Fe3O4, which indicates that chemisorption is likely the predominant adsorption mechanism47.

Adsorption Isotherms

The equilibrium adsorption experiments were carried out using municipal wastewater spiked with different concentrations of Cr(VI) ions, ranging from 10 to 100 mg/L. Figure 9 illustrates the quantity of Cr(VI) adsorbed at equilibrium, denoted as qe (mg/g), in relation to the equilibrium concentration, Ce (mg/L). To analyze the equilibrium data, the two most frequently utilized equilibrium isotherm models were applied, specifically the Freundlich and single-site Langmuir isotherm models. The single-site Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms, in their non-linear forms, are represented by Eqs. (14) and (15), respectively. Relevant isotherm parameters obtained from both linearized and nonlinear isotherm models are given in Table 5.

The adsorption parameters obtained from both Langmuir and Freundlich models, using nonlinear and linear methods, reveal slight variations in their representation of the adsorption process. For the Langmuir isotherm, the linear model shows a better fit, with a higher R2 value (0.906) compared to the nonlinear model (0.805), suggesting a more accurate description of monolayer adsorption. However, the nonlinear model exhibits slightly lower error values for all metrics, including X2, ARE, RMSE and HYBRID, indicating it might more accurately represent the actual interactions and dynamics occurring during adsorption. Both approaches predict similar maximum adsorption capacities and equilibrium constants, highlighting the reliability of Langmuir parameters across different fitting approaches.

For the Freundlich isotherm, the nonlinear model achieves a better fit with a higher R2 value (0.914) and lower error values for X2, RMSE and HYBRID compared to the linear model. This suggests that the nonlinear Freundlich model more accurately reflects the adsorption process, particularly for heterogeneous surfaces. The adsorption intensity (n > 1) and KF values from both methods indicate favorable adsorption, though the linear model predicts slightly higher KF. Overall, the multilayer Freundlich isotherm model exhibited better descriptive data fitting, yielding higher R2 and lower error values than the single-site Langmuir model. The fitness of the multilayer Freundlich isotherm model indicates the presence of heterogeneous adsorption sites. The Kf value for Cr (VI) adsorption on rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites, derived from the Freundlich model was 0.82, comparable to various carbon-based adsorbents reported in the literature. Table 6 demonstrates the comparison of Cr (VI) adsorption efficacy of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposites with other carbon-based adsorbents. rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposite in this study achieves rapid equilibrium with a shorter contact time (40 min) when compared to other adsorbents in the literature, including polyethyleneimine-multi-walled carbon nanotube (PEI-MWCNTs)48, multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)49 and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), ferric oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (α-FeOOH NPs)50 and rice straw51. Addition to that, rGO@Fe3O4 demonstrates a comparable adsorption capacity to these adsorbents, while offering a significant practical advantage due to its magnetic nature, which enables easy separation of adsorbents from aqueous solution.

Potential mechanism for adsorption

Chromium ions undergo the following reactions in aqueous solution52:

In acidic medium, chromium ions primarily exist as \({\text{HCrO}}_{4}^{-}\) . However, as the pH increases above 6.0, \({\text{CrO}}_{4}^{2-}\) and \({\text{Cr}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{7}^{2-}\) become the predominant species53. Simultaneously, metal oxide nanoparticles show the following reaction mechanism due to the protonation or deprotonation of the surface depending on the solution pH54:

Under acidic conditions, a strong electrostatic attraction exists between the positively charged surface of the rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposite and Cr(VI) species. As the pH increases, the surface of the nanocomposite becomes less protonated, reducing its positive charge, and thus decreasing Cr(VI) adsorption. Moreover, the higher concentration of hydroxyl ions in the solution creates a competitive adsorption environment, further reducing Cr(VI) removal efficiency. Therefore, electrostatic attraction is likely primary mechanism driving Cr(VI) adsorption. Addition to that, previous studies on Cr(VI) removal using graphenic materials emphasize the role of aromatic carbon and oxygen-containing functional groups in Cr(VI) reduction55. The FTIR spectra of rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposite before and after Cr(VI) adsorption, given in Fig. 10, show significant changes, confirming adsorption. The absorption bands, appeared at 1061 cm−1 and 1115 cm−1, respectively, were attributed to the presence of C–O–C and C–O stretching vibrations in epoxy or carboxyl groups in rGO structure. The decrease in the intensity of these peaks indicates the involvement of these functional groups in Cr(VI) binding. These groups act as electron donors and partially reduce Cr(VI) ions to non-toxic Cr(III), leading to enhanced adsorption56,57. Further confirmation of Cr(VI) adsorption onto rGO@Fe3O4 nanocomposite was obtained through FESEM and EDS analysis of structure conducted before and after adsorption. Figure 11a and b present FESEM micrographs of rGO@Fe3O4 before and after Cr(VI) adsorption, revealing an increase in surface roughness. Additionally, the EDS spectrum given in Fig. 11c confirms the presence of Fe (71.5%), C (6.1%), O (22%) and Cr (0.3%) by weight percentage, indicating the successful adsorption of Cr(VI) onto rGO@Fe3O4. The possible adsorption mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Conclusion

Chromium contamination resulting in environmental pollution is a critical problem in the modern world. In this study, sphere-like formations of rGO@Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposites were effectively synthesized, successfully characterized, and assessed for their potential to adsorb Cr (VI) ions from municipal wastewater. Batch experiments indicated that the effectiveness of Cr (VI) removal was affected by multiple variables, namely, the quantity of adsorbent, the initial concentration of Cr (VI), and the duration of agitation in the solution. rGO@Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposites displayed notable Cr (VI) removal efficacy throughout a wide pH spectrum. The nanocomposite exhibited adsorption effectiveness, achieving an adsorption capacity of 5.15 mg/g.

Kinetic studies were evaluated through the application of two models: PFO, PSO, and their nonlinear forms. The experimental data aligned with both the linearized and nonlinear PSO modeling, indicating that the rate-limiting step for the adsorption of Cr (VI) onto the adsorbent is chemisorption. The FT-IR analysis of the adsorbent, both prior to and following the adsorption process, illustrates the involvement of functional groups in the nanocomposite in the adsorption process. Thus, the adsorption process is mainly determined by the combination of electrostatic forces, surface complex formation via chemisorption, and the partial reduction of adsorbed Cr (VI) to Cr (III). The Freundlich isotherm model effectively simulated the equilibrium data of Cr (VI) adsorption, suggesting that the adsorption process involves heterogeneous surface interactions. The results highlight the promising potential of rGO@Fe₃O₄ nanocomposites and support the use of these nanocomposites in wastewater treatment, particularly for the removal of toxic Cr (VI) ions.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request. Kindly contact with the corresponding author.

References

Gabisa, E. W. & Ratanatamskul, C. Effects of operating conditions on removal of microplastics (PET, PP, PS) from wastewater by electrocoagulation systems and kinetics of chromium removal in the presence of microplastics. J. Water Process Eng. 61, 105313 (2024).

Hojabri, S., Rajic, L., Zhao, Y. & Alshawabkeh, A. N. Simulation of hexavalent chromium removal by electrocoagulation using iron anode in flow-through reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 476, 135195 (2024).

Wittbrodt, P. R. & Palmer, C. D. Reduction of Cr(VI) in the presence of excess soil fulvic acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29, 255–263 (1995).

Zelmanov, G. & Semiat, R. Iron (Fe+3) oxide/hydroxide nanoparticles-based agglomerates suspension as adsorbent for chromium (Cr+6) removal from water and recovery. Sep. Purif. Technol. 80, 330–337 (2011).

Rahman, Z. & Thomas, L. Chemical-assisted microbially mediated chromium (Cr) (VI) Reduction under the influence of various electron donors, redox mediators, and other additives: An outlook on enhanced Cr(VI) removal. Front. Microbiol. 11, 619766 (2021).

Jiang, B., Niu, Q., Li, C., Oturan, N. & Oturan, M. A. Outstanding performance of electro-Fenton process for efficient decontamination of Cr(III) complexes via alkaline precipitation with no accumulation of Cr(VI): Important roles of iron species. Appl. Catal. B 272, 119002 (2020).

Tan, H. et al. Bioreduction and biosorption of Cr(VI) by a novel Bacillus sp. CRB-B1 strain. J. Hazard. Mater. 386, 121628 (2020).

Li, H. Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, M., Wei, W. & Xie, B. A novel anion exchange method based on in situ selectively reductive desorption of Cr(VI) for its separation from V(V): Toward the comprehensive use of hazardous wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 368, 670–679 (2019).

Islam, M. A., Angove, M. J. & Morton, D. W. Recent innovative research on chromium (VI) adsorption mechanism. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 12, 100267 (2019).

Hoslett, J. et al. Surface water filtration using granular media and membranes: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 639, 1268–1282 (2018).

Tahreen, A., Jami, M. S. & Ali, F. Role of electrocoagulation in wastewater treatment: A developmental review. J. Water Process. Eng. 37, 101440 (2020).

Ukhurebor, K. E. et al. Effect of hexavalent chromium on the environment and removal techniques: A review. J. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111809 (2021).

Laskaridis, A., Sarakatsianos, I., Tzollas, N. & Katsoyiannis, I. A. Simultaneous removal of arsenate and chromate from ground- and surface- waters by iron-based redox assisted coagulation. Sustainability 12, 5394 (2020).

Kasavo, R. N., Bhaumik, M. & Brink, H. G. Removal of chromium from aqueous solution using a nanocomposite of nickel ferrite and polyaniline doped with 2-naphthalene sulfonic acid. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111229 (2023).

Ojovan, M. I. & Lee, W. E. Treatment of Radioactive Wastes. In An Introduction to Nuclear Waste Immobilisation 149–178 (2005) https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044462-8/50016-8.

Mazur, L. P., Cechinel, M. A. P., de Souza, S. M. A. G. U., Boaventura, R. A. R. & Vilar, V. J. P. Brown marine macroalgae as natural cation exchangers for toxic metal removal from industrial wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 223, 215–253 (2018).

Azeez, N. A., Dash, S. S., Gummadi, S. N. & Deepa, V. S. Nano-remediation of toxic heavy metal contamination: Hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)]. Chemosphere https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129204 (2021).

Arishi, A. & Mashhour, I. Microbial mechanisms for remediation of hexavalent chromium and their large-scale applications: Current research and future directions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 15, 53–67. https://doi.org/10.22207/JPAM.15.1.32 (2021).

Kerur, S. S. et al. Removal of hexavalent chromium-industry treated water and wastewater: A review. Mater. Today: Proc. 42, 1112–1121 (2020).

Aryanti, P. T. P., Nugroho, F. A., Phalakornkule, C. & Kadier, A. Energy efficiency in electrocoagulation processes for sustainable water and wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114124 (2024).

Hu, J., Chen, G. & Lo, I. M. C. Removal and recovery of Cr(VI) from wastewater by maghemite nanoparticles. Water Res. 39, 4528–4536 (2005).

Mabalane, K., Shooto, N. D. & Thabede, P. M. A novel permanganate and peroxide carbon-based avocado seed waste for the adsorption of manganese and chromium ions from water. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 10, 100782 (2024).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Facial conjugate adsorbent for sustainable Pb(II) ion monitoring and removal from contaminated water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 673, 131794 (2023).

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Da’ana, D. A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 393, 122383 (2020).

Bao, S. et al. PEI grafted amino-functionalized graphene oxide nanosheets for ultrafast and high selectivity removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions by adsorption combined with reduction: Behaviors and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 399, 125762 (2020).

Qalyoubi, L., Zuburtikudis, I., Abu Khalifeh, H. & Nashef, E. Adsorptive membranes incorporating ionic liquids (ILs), deep eutectic solvents (DESs) or graphene oxide (GO) for metal salts extraction from aqueous feed. Membranes 13, 874 (2023).

Shaban, M., Abukhadra, M. R., Rabia, M., Elkader, Y. A. & Abd El-Halim, M. R. Investigation the adsorption properties of graphene oxide and polyaniline nano/micro structures for efficient removal of toxic Cr(VI) contaminants from aqueous solutions; kinetic and equilibrium studies. Rendiconti Lincei 29, 141–154 (2018).

Abbas, R. F., Hassan, M. J. M. & Rheima, A. M. Adsorption of fast green dye onto Fe3O4 MNPs and GO/Fe3O4 MNPs synthesized by photo-irradiation method: Isotherms, thermodynamics, kinetics, and reuse studies. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 6, 100104 (2024).

Hummers, W. S. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. (1958).

Er, E. Ö., Çağlak, A., Engin, G. Ö. & Bakirdere, S. Ultrasound-assisted dispersive solid phase extraction based on Fe3O4/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for the determination of 4-tert octylphenol and atrazine by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Microchem. J. 146, 423–428 (2019).

Grigoraș, C. G., Simion, A. I., Favier, L., Drob, C. & Gavrilă, L. Performance of dye removal from single and binary component systems by adsorption on composite hydrogel beads derived from fruits wastes entrapped in natural polymeric matrix. Gels 8, 795 (2022).

Bezerra, M. A., Santelli, R. E., Oliveira, E. P., Villar, L. S. & Escaleira, L. A. Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta 76, 965–977 (2008).

Çiplak, Z., Yildiz, N. & Cąlimli, A. Investigation of graphene/Ag nanocomposites synthesis parameters for two different synthesis methods. Fullerenes, Nanotubes, Carbon Nanostruct. 23, 361–370 (2015).

Aigbe, U. O., Maluleke, R., Lebepe, T. C., Oluwafemi, O. S. & Osibote, O. A. Rhodamine 6G dye adsorption using magnetic nanoparticles synthesized with the support of Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract (bitter leaf). J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 33, 4012–4031 (2023).

Aigbe, U. O., Lebepe, T. C., Oluwafemi, O. S. & Osibote, O. A. Prediction and optimizing of methylene blue sequestration to activated charcoal/magnetic nanocomposites using artificial neutral network and response surface methodology. Chemosphere 355, 141751 (2024).

Oroujeni, M., Kaboudin, B., Xia, W., Jönsson, P. & Ossipov, D. A. Conjugation of cyclodextrin to magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles via polydopamine coating for drug delivery. Prog. Org. Coat. 114, 154–161 (2018).

Kromah, V. & Zhang, G. Aqueous adsorption of heavy metals on metal sulfide nanomaterials: Synthesis and application. Water 13, 1843 (2021).

Du, Z. et al. One-pot hydrothermal preparation of Fe3O4 decorated graphene for microwave absorption. Materials 13, 3065 (2020).

Monshi, A. et al. Modified Scherrer equation to estimate more accurately nano-crystallite size using XRD. World J. Nano Sci. Eng. 2, 154–160 (2012).

Nasiri, S. et al. Modified Scherrer equation to calculate crystal size by XRD with high accuracy, examples Fe2O3, TiO2 and V2O5. Nano Trends 3, 100015 (2023).

Mohammad, F. Z. et al. Light weight RGO/Fe3O4 nanocomposite for efficient electromagnetic absorption coating in X-band. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 29, 19775–19782 (2018).

Zhao, D. et al. Facile preparation of amino functionalized graphene oxide decorated with Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the adsorption of Cr(VI). Appl Surf Sci 384, 1–9 (2016).

Zeng, Q. et al. Efficient removal of hexavalent chromium in a wide pH range by composite of SiO2 supported nano ferrous oxalate. Chem. Eng. J. 383, 123209 (2020).

Liu, L., Sun, P., Chen, Y., Li, X. & Zheng, X. Distinct chromium removal mechanisms by iron-modified biochar under varying pH: Role of iron and chromium speciation. Chemosphere 331, 138796 (2023).

Balan, C., Volf, I. & Bilba, D. Uklanjanje hroma (VI) iz vodenih rastvora pomoću purolita - Bazne anjonske smole sa gel strukturom. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 19, 615–628 (2013).

Goharshadi, E. K. & Moghaddam, M. B. Adsorption of hexavalent chromium ions from aqueous solution by graphene nanosheets: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 12, 2153–2160 (2015).

Qi, J., Zhang, G. & Li, H. Efficient removal of arsenic from water using a granular adsorbent: Fe–Mn binary oxide impregnated chitosan bead. Bioresour. Technol. 193, 243–249 (2015).

Sambaza, S. S., Masheane, M. L., Malinga, S. P., Nxumalo, E. N. & Mhlanga, S. D. Polyethyleneimine-carbon nanotube polymeric nanocomposite adsorbents for the removal of Cr6+ from water. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C 100, 236–246 (2017).

Dehghani, M. H. et al. Removal of noxious Cr (VI) ions using single-walled carbon nanotubes and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 279, 344–352 (2015).

Guo, N. et al. Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution by mesoporous α-FeOOH nanoparticles: Performance and mechanism. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 299, 110101 (2020).

Gao, H. et al. Characterization of Cr(VI) removal from aqueous solutions by a surplus agricultural waste—rice straw. J. Hazard. Mater. 150, 446–452 (2008).

Emamy, F. H., Bumajdad, A. & Lukaszewicz, J. P. Adsorption of hexavalent chromium and divalent lead ions on the nitrogen-enriched chitosan-based activated carbon. Nanomaterials 11, 1907 (2021).

Khare, N., Bajpai, J. & Bajpai, A. K. Graphene coated iron oxide (GCIO) nanoparticles as efficient adsorbent for removal of chromium ions: Preparation, characterization and batch adsorption studies. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 10, 148–162 (2018).

Nassar, N. N. Rapid removal and recovery of Pb(II) from wastewater by magnetic nanoadsorbents. J. Hazard. Mater. 184, 538–546 (2010).

Wang, D. et al. Synthesis of a multifunctional graphene oxide-based magnetic nanocomposite for efficient removal of Cr(VI). Langmuir 33, 7007–7014 (2017).

Philip, R. S. & Mathew, M. Hexavalent chromium removal using reduced graphene oxide-zinc oxide composite fabricated via simple pyrolysis method. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 19, 100535 (2024).

Dubey, R., Bajpai, J. & Bajpai, A. K. Green synthesis of graphene sand composite (GSC) as novel adsorbent for efficient removal of Cr (VI) ions from aqueous solution. J. Water Process Eng. 5, 83–94 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank İstanbul Technical University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit for the project supported in Project Number: MGA-2023-44569.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G., N.K.Z and B.T.Z. conducted experiments, wrote the main text and prepared figures and tables. S.B. and E.Ö.E. supervised the findings of this work. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. S.B. and E.Ö.E. conceived the study and were in charge of overall direction and planning.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gürsoy, S., Zeytinci, N.K., Zaman, B.T. et al. Study of linear and nonlinear isotherm and kinetic parameters of hexavalent chromium adsorption onto reduced graphene oxide coated iron oxide. Sci Rep 15, 25206 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97588-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97588-x