Abstract

Field observations during summer-fall of 2018 in the Antarctic Peninsula region provided the first morphological evidence that under certain environmental conditions, Salpa thompsoni blastozooid development can deviate from its traditional sequential protogynous hermaphroditism (SPH). Early male testis development at female blastozooid stages points to a wide-spread overlapping protogynous hermaphroditism (OPH) in regions where warm Antarctic Circumpolar Current waters mix with colder Antarctic Coastal waters. Our findings highlight the importance of the environmental setting in determining the reproductive pathway in S. thompsoni. OPH was observed in cooler and less productive waters, while SPH occured in both warmer and cooler productive waters. It appears that food availability may offset the effect of decreasing water temperatures for warm-water S. thompsoni reproductive development. It is plausible that OPH may permit the establishment of the S. thompsoni populations in the high Antarctic under the warming trend in the Southern Ocean by allowing for more efficient reproduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pelagic thaliaceans, including salps, pyrosomes and doliolids, are a conspicuous and prominent group of gelatinous organisms found throughout the world`s oceans contributing significantly to zooplankton biomass, organic matter cycling and carbon sequestration1,2. Their life cycles follow metagenesis, a process through which one generation of animals reproduce asexually before giving birth to a sexually reproducing generation. Despite the inherent complexity of pelagic tunicate life cycles, all their life histories are shaped to maximize reproductive output over a short period. In their review, Alldredge and Madin3 highlighted several key traits that allow tunicates to achieve a rapid population increase in unpredictable environments. These traits include efficient feeding, rapid growth and high fecundity, short generation times, direct development, viviparity, alteration of generations and hermaphroditism.

Among pelagic thaliaceans, salps have a particularly complex life cycle and proliferate through an obligatory alternation of oozooid asexual and blastozooid sexual generations3. Sequential hermaphroditism described in salps suggests that blastozooid females arranged in chains of a few hundred genetically identical individuals possesses a single, fully formed and ready for fertilization egg4. The moment blastozooids ‘inhale’ water first time after being released, they are usually fertilized by a male-stage blastozooid, which releases sperm into the water5. The fertilized egg then develops into an embryo, which is a precursor of the oozooid. Upon the embryo release, the blastozooid female develops testis becoming a functional male6. There is an indication that recently released blastozooids, while possessing a fully developed egg, also inherit the precursor cells of sperm that are rudiments of the future testis4,6. By default, the testis development is only initiated after the embryo is fully developed and released6. It is unclear when the development of the testis is initiated, but to avoid self-fertilization it is thought to be delayed till the developed embryo is discharged6,7. However, Purcell and Madin8 mentioned that “During development of the embryo, the parent aggregate salp becomes a functional male, releasing sperm into the water for the fertilization of other, younger aggregates.” The latter observations are however lacking.

During summer-fall of 2018 in the western Antarctic Peninsula, we had a unique opportunity to study the Salpa thompsoni population with a particular emphasis on its stage of development in various water masses. During this expedition, blastozooids that were functional females with embryos at the terminal developmental stage already possessed fully developed male testes9,10. We aimed to investigate first, the stage development of S. thompsoni in contrasting water masses, examining how environmental variability influences its life cycle. Secondly, we aimed to examine whether embryo and testis development in S. thompsoni blastozooids occur in a sequential or parallel manner, thereby providing novel insights into their reproductive flexibility and adaptive capacity in response to changing environmental conditions.

Materials and methods

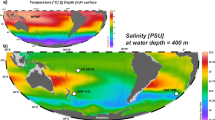

Salps were collected at 58 stations using mainly the 2.5 m2 Isaacs-Kidd Midwater Trawl equipped with the 0.5 mm mesh during March-May 2018 onboard RV Polarstern (Fig. 1). Samples were collected during the double oblique tows down to ~ 170 m at the speed of 2-2.5 knots. In all catches, if present, salps were counted, sexed, staged, and oral-atrial length (OAL) measured to the nearest mm. Oozooids (solitaries) as well as large blastozooids (aggregates) were analysed from the entire catch. The remaining catch was subsampled (1/4 to 1/40 fraction of the sample) to obtain minimum 150–350 small blastozooids for detailed biological analysis. The environmental data were collected using the CTD Seabird by generally deploying (downward cast) it to a depth of 500 m at every station. In the current study, only surface environmental data, where salps concentrate during nighttime, were used.

All stations sampled during March-May 2018 onboard RV Polarstern. BS/DI – Bransfield Strait and Deception Island region; NSSI – north of South Shetland Islands region; EI – Elephant Island vicinity region. Red squares include stations used for the salp development analyses and to calculate environmental parameters presented in Table 1. The map was created using the ODV sofware version 5.6.5 (Schlitzer, Reiner, Ocean Data View (https://odv.awi.de), 2023).

In this study, we only focus on development of S. thompsoni blastozooids. Their maturity stages have been well described11,12,13. In short, five different blastozooid stages (from 0 to 4) were classified according to the gradual growth of the embryo. At stage 0, the ovarian sac is spherical with no sign of embryo development. By stage 4, the embryo (≥ 4 mm in length) resembles features the early oozooid11,12. Stage S or ‘spent’ was identified by the presence of a placenta scar indicating that embryo was recently released. Blastozooids with visible placenta scar and sperm channels on the salp nucleus were classified as males (stage M). However, during the biological analysis of salps, we paid particular attention to sperm channels on the salp nucleus at all stages of development. If sperm channels were visible, the particular stage was classified with letter “M”. For example, if the embryo development was on stage 2 but showed beginning of the sperm channel development, it was classified as blastozooid stage 2 M. Finally, blastozooids with no visible embryos (possibly failed fertilization) or embryos that showed a remnant of some degree of development (possibly embryos with a disrupted development), no visible placenta scar, no visible sperm canals were classified following Chiba et al.14 as stage X.

Results

Oceanographic setting

The three regions under investigation differed in their oceanographic setting. The north of South Shetland Islands (NSSI) region was influenced exclusively by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), with the highest mean sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a concentrations (Table 1). The Bransfield Strait/Discovery Island (BS/DI) region was also primarily impacted by the southern branch of the ACC, with some mixing with the Antarctic Coastal Current waters. The water mass in this region, while having the lowest mean surface temperature, was similar in chlorophyll-a concentrations to the NSSI region (Table 1). The Elephant Island (EI) region generally represented a mixing zone between the ACC waters (particularly at stations far north of EI) and the mixture of the Antarctic Coastal Current and Weddell Sea waters. The latter water masses dominated the region near the EI and south of it. The waters near the EI had average surface temperatures similar to those of the BS/DI region, but with the lowest chlorophyll-a concentrations (Table 1). Hence, generally three regions under investigation can be characterized as: warm and productive (NSSI), cool and productive (BS/DI) and cool and non-productive (EI) (Table 1).

Salp development dynamics.

The sampling in all three regions lasted less than three weeks and temporal variations in environmental conditions were minimal. Nevertheless, there was a conspicuous difference in the S. thompsoni development dynamics between the three regions. Fitting the classical paradigm, there was a remarkable similarity in the S. thompsoni development in the BS/DI and NSSI regions (Fig. 2A and B). There was a robust length-related development of salp blastozooids and males (M stage) started appearing in the population at OAL 26–30 mm, reaching 50% of blastozooids by length of ~ 34 mm, and by length of 41–43 mm all blastozooids were males (Figs. 2A, B and 3A, B). It was also clear that M stage only appeared after salp released small oozooids (Fig. 2A, B).

Population dynamics of S. thompsoni in the EI region was strikingly different (Figs. 2C and 3C). First, there was a distinguishable overlap in the appearance of male testes in early blastozooids. This occurred as early as at stage 2 and the salp OAL of 14 mm (Fig. 2C). Second, the 50% blastozooids at the OAL of 26 mm had testes at various stages of development (Fig. 3C). Finally, by length of 37 mm all blastozooids could be classified as males (Fig. 3C).

The size and stage development photographic sequence collected in the vicinity of the Elephant Island is shown in Fig. 4. It shows the visible initiation of the testis canal development at the blastozooid stage 2 at a OAL of 15 mm (Fig. 4C). The canals develop fast and by stage 3 (Fig. 4D and E) testes may become functional since mechanical disturbance (needle touching) during the biological analysis often triggered the sperm release in freshly caught blastozooids (E.A Pakhomov, personal observation). Finally, we observed large blastozooids with both embryos and fully developed visible testes (Fig. 4I).

A sequence of Salpa thompsoni blastozooid nuclei in the proximity of the Elephant Island during summer-fall of 2018. (A) No testes, stage 1 blastozooid Oral Atrial Length (OAL) 10 mm; (B) no testes, stage 2 blastozooid, OAL 13 mm; (C) early testes, stage 2 M blastozooid, OAL 15 mm; (D) developing testes, stage 3 M blastozooid, OAL 20 mm; (E) well developed testes, stage 3 M blastozooid, OAL 28 mm; (F) developed testes, stage 4 M blastozooid, OAL 31 mm; (G) developed testes, stage Spent M blastozooid, OAL 38 mm; (H) developed testes, functional male blastozooid, OAL 40 mm; (I) functional male blastozooid with the embryo still inside, OAL 45 mm.

Discussion

It has been documented that the stage development in pelagic tunicates is mainly modulated by environmental temperature, food availability and quality15,16,17. The observed differences in blastozooid development (SPH vs. OPH) in regions influenced by either the ACC or Antarctic Coastal Current/Weddell Sea waters- documented for the first time to our knowledge- are striking and have ecologically important implications for the populations of S. thompsoni in the high Antarctic regions. It appears that S. thompsoni under certain conditions may deviate from the traditional sequential protogynous hermaphroditism (SPH) by the overlapping development of male testes, which should be called overlapping protogynous hermaphroditism (OPH). This phenomenon was previously suggested for Cyclosalpa bakeri by Purcell and Madin8 and was recently observed during lab-based experiments under controlled conditions for S. fusiformis, a species closely related both morphologically and taxonomically to S. thompsoni18. Our findings highlight the importance of the environmental setting in determining which pathway is triggered. OPH was observed in cooler and less productive waters, while SPH emerged in both warmer and cooler, but more productive, environments. It comes across that the food availability may offset the effect of decreasing water temperatures for warm-water S. thompsoni. However, this observation warrants further experimental investigation to fully understand the underlying mechanisms.

At this point, we can only hypothesize that cool temperatures and low food availability triggered the parallel development of embryo and testis. It is important to note that our observations were based solely on the visible morphological expressions of testis development. However, recent transcriptomic analysis of S. thompsoni sexual reproductive stages identified genes linked to the male sex differentiation and spermatogenesis as soon as the egg is fertilized and definitely before the embryo is released19. Our morphological evidence is thus consistent with genetic findings, further challenging the conventional understanding of the reproductive processes in S. thompsoni. It is plausible that, to avoid self-fertilization, an internal biological clock triggers testis development after a specific time to ensure egg fertilization by older blastozooids. In the typical salp habitat (such as ACC-influenced region), which is warmer and moderately productive, the egg development occurs faster, thus showing a pathway that closely resembles SPH. Also, SPH would persist even in colder but productive waters as food availability may buffer slower development caused by colder water temperatures. However, in cold and unproductive waters, salp egg development takes longer, overlapping with the onset of testis development, leading to the OPH pathway. It is also possible that during the female stage, blastozooids may expedite to becoming males, perhaps at the expense of lowering their growth rates. These potential scenarios warrant further investigation using field and transcriptomic studies.

Besides C. bakeri and S. thompsoni, OPH has also been observed in S. fusiformis blastozooids. During a laboratory experiment, S. fusiformis kept under controlled conditions in kreisel tanks developed testes while the embryo was still developing18. Interestingly, this included individuals that had not been previously fertilized, indicating further the presence of new developmental pathways that may be in contrast to the classic protogynous hermaphroditism and somewhat influenced by time-regulated physiological mechanisms18. Gene expression patterns in a follow-up study demonstrated that the salp life cycle may physiologically prepare blastozooids for reproduction during the potential reproductive period, regardless of the fertilization status (Müller, personal communication). This may be a mechanism facilitating a rapid response to favorable environmental conditions. However, since these studies were conducted under controlled conditions that only mirror in situ environments, potential triggers such as temperature and food availability may still modulate different developmental pathways in natural environments as it was observed in the present study.

Previous studies suggested that S. thompsoni may complete at least two full life cycles (from egg-to-egg development) during the austral summer in regions affected by the ACC waters16,20,21. The recent southward expansion of S. thompsoni may thus revert to one cycle, as exposure to cold (< 0 oC) and unproductive waters may significantly slow down their development, preventing the completion of the egg-to-egg cycle in the high Antarctic16. As a result, the southward expansion remains challenging, with no established S. thompsoni populations currently found in the high Antarctic. Their occasional appearance in these regions is likely due to lateral advection, where seeding salp specimens are transported southward beyond the Southern Boundary Front13,22.

Salps may already be set for reproductive success at birth, increasing the potential for bloom formation as ocean temperatures rise6,19. However, it appears that in the real world, the first crop of blastozooid chains from a single oozooid may end up with unfertilized eggs unless there are other oozooids present that release blastozooids early enough, allowing them to develop into males. In case of a single oozooid, it is not clear whether blastozooid chains with unfertilized eggs will develop testes instead, or simply grow, and become males that produce gametes and thus can fertilize the second crop of blastozooid chains. This, however, has limitations because genetically identical specimens will cross-fertilize, curtailing genetic radiation. In fact, the protogynous hermaphroditism has been hypothesized to prevent self-fertilization6. Such reproductive strategy would explain the challenges of salp population establishment in new habitats. When only a limited number of salp oozooids are advected southward, the low population density significantly reduces the likelihood of meeting each other, hindering successful reproduction. Hence, for the salp population establishment in the high Antarctic, the advection of numerous oozooids at various stages of development is important. In addition, the short productive period in the high Antarctic further complicates salp proliferation. However, these environmental constraints may shift under the ongoing warming trend in the Southern Ocean. The shift to alternative hermaphroditic pathways, and particularly to OPH, could therefore facilitate the establishment and persistence of the S. thompsoni populations in the high Antarctic.

Data availability

“The biological datasets used and/or analysed the current study available form the corresponding author on reasonable request. Raw CTD data are published in PANGAEA: Meyer, Bettina; Rohardt, Gerd (2018): CTD raw data files from POLARSTERN cruise PS112, link to tar-archive [dataset]. Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.895969.”

References

Bone, Q. (ed) The Pelagic Tunicates (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Henschke, N. et al. Rethinking the role of salps in the ocean. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 720–733 (2006).

Alldredge, A. L. & Madin, L. P. Pelagic tunicates: Unique herbivores in the marine plankton. BioSci 32, 655–663 (1982).

Delage, Y. & Hérouard, E. Les procordés. Traité de Zoologie Concréte Volume VIII. Paris (France): Schleicher Frères. (1898).

Holland, L. Z. & Tunicates Curr. Biol. 26, R141–R156. (2016).

Piette, J. & Lemaire, P. Thaliaceans, the neglected pelagic relatives of ascidians: A developmental and evolutionary enigma. Q. Rev. Biol. 90, 117–145 (2015).

Brooks, W. K. A remarkable life history and its meaning. Amer Nat. 10, 641–656 (1876).

Purcell, J. P. & Madin, L. P. Diel patterns of migration, feeding, and spawning by salps in the Subarctic Pacific. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 73, 211–217 (1991).

Pakhomov, E. A. et al. Biology of the pelagic tunicate, Salpa thompsoni, in the Western Atlantic sector of the Southern ocean during March-May 2018. Rep. Polar Mar. Res. 722, 28–33 (2018).

Müller, S. J. et al. Seasonal and form-specific gene expression signatures uncover different generational strategies of the pelagic tunicate Salpa thompsoni during the Southern ocean winter. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 914095. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.914095 (2022).

Foxton, P. The distribution and life history of Salpa thompsoni Foxton with observations on a related species S. gerlachei Foxton. Disc Rep. 34, 1–116 (1966).

Daponte, M. C., Capitanio, F. L. & Esnal, G. B. A mechanism for swarming in the tunicate Salpa thompsoni (Foxton, 1961). Ant Sci. 13, 240–245 (2001).

Pakhomov, E. A. et al. Biology and life cycles of pelagic tunicates in the Lazarev Sea, Southern ocean. Deep-Sea Res. II. 58, 1677–1689 (2011).

Chiba, S. et al. Population structure change of Salpa thompsoni from Austral mid-summer to autumn. Polar Biol. 22, 341–349 (1999).

Henschke, N. et al. Modelling the life cycle of Salpa thompsoni. Ecol. Model. 387, 17–26 (2018). https://doi.org/j.ecolmodel.2018.08.017

Henschke, N. & Pakhomov, E. A. Latitudinal variations in Salpa thompsoni reproductive fitness. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11061 (2019).

Minkina, N. I., Samyshev, E. Z. & Pakhomov, E. A. Temporal and Spatial variability in metabolism of the Antarctic pelagic tunicate Salpa thompsoni Foxton, 1961. Mar. Biol. Res. 20, 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451000.2024.2342260 (2024).

Müller, S. J. et al. A temperature-controlled, circular maintenance system for studying growth and development of pelagic tunicates (Salps). Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 22, 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10605 (2024).

Castellano, K. R. et al. Salpa genome and developmental transcriptome analyses reveal molecular flexibility enabling reproductive success in a rapidly changing environment. Sci. Rep. 13, 21056. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47429-6 (2023).

Pakhomov, E. A. & Hunt, B. P. V. Trans-Atlantic variability in ecology of the pelagic tunicate Salpa thompsoni near the Antarctic Polar front. Deep-Sea Res. II. 138, 126–140 (2017).

Lüskow, F. et al. Biology of Salpa thompsoni at the Chatham rise, new Zealand: Demography, growth, and diel vertical migration. Mar. Biol. 167, 175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-020-03775-x (2020).

Pakhomov, E. A., Froneman, P. W. & Perissinotto, R. Salp/krill interactions in the Southern Ocean: Spatial segregation and implications for the carbon flux. Deep-Sea Res. II. 49, 1881–1907 (2002).

Acknowledgements

“We thank the captain, crew and the scientific staff of R.V. Polarstern cruise PS112 for support during our samplings. This research was supported by the NSERC Discovery Grant RGPIN-2014-05107 to E.A.P. S.J.M was supported by the Presidential Board`s programme (PH-F funding) by the University of Oldenburg and by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). The work contributes to the Helmholtz Research Program “Changing Earth—Sustaining our future” of the research field Earth and Environment of the Helmholtz Association, Topic 6, Subtopic 6.1. and 6.2.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“E.A.P. conceived the study, collected samples, and performed the analysis with the support of S.J.M. and B.M. E.A.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, revised the manuscript, and approved the submitted version.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pakhomov, E.A., Müller, S.J. & Meyer, B. Environmental conditions modulate hermaphroditic pathways in Salpa thompsoni near the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Sci Rep 15, 13738 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97608-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97608-w