Abstract

Fin whales, the second largest animal on Earth, produce one of the most intense vocalisations in the animal kingdom. Monitoring these songs using ocean-deployed hydrophones plays an important role in the study of fin whale distribution and social behaviour, though obtaining real-time data remains challenging. In this feasibility study we investigate if vocalising near-coastal fin whales can be widely detected and located with onshore seismometers. Inspecting data from pre-existing seismic installations we establish that fin whale song can be detected with onshore seismometers up to 5.5 km inland, across multiple marine environments, globally. Individual creatures can be located and tracked through the analysis of seismic wave properties. Furthermore, we show that citizen science seismometers, such as the affordable and widely deployed ‘Raspberry Shake’ devices, can reliably detect fin whale song. These instruments, often placed in coastal areas, provide real-time data, offering a cost-effective and accessible method for monitoring coastal fin whale activity. The revelation that human living spaces are ensonified by fin whale song offers the potential to enhance public engagement with the oceans and presents new opportunities for global monitoring. Fin whales are vulnerable to noise pollution, shipping strikes and entanglement in fishing gear. The use of terrestrial seismometers could improve early warning systems and contribute to richer datasets on near coastal whale vocalisations. This study demonstrates that, globally, seismic data holds significant untapped potential for near-coastal fin whale monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), a vulnerable1 cetacean species, occurs worldwide mainly in offshore waters of the temperate and subpolar zones2. Their songs, reported to have mean source levels of up to 190 dB re 1 µPa at 1 m (e.g. 189.9 ± 5.8 dB3, 160–186 dB4, 189 ± 4 dB5, 190.5 ± 7.4 dB6), rank among the most powerful animal vocalisations on Earth3,4,7. These potent vocalisations propagate through the water column and can reliably be detected over many tens of kilometres, and often hundreds of kilometres7,8,9,10, facilitating the study of fin whale abundance and distribution using acoustics sensors (hydrophones) at sea e.g.11,12,13,14,15. Nonetheless, fin whale seasonal movements are less well understood than for other baleen whales2. While most fin whale populations are thought to show seasonal shifts toward the poles for feeding in the summer and towards the subtropics for calving and mating in the winter10, some populations such as those in the Gulf of California, the East China Sea and the Mediterranean Sea appear to be resident year-round16,17,18. There is also evidence that, especially in the northern hemisphere, some fin whales remain throughout the year near polar19,20 and subtropical latitudes10. While sightings from both land and ships are important monitoring tools21,22 they suffer from significant sampling bias in space and time. When available, hydrophone recordings of vocalisations hold rich information both on the animal’s presence and social behaviour. Fin whale songs mainly consist of regular sequences of short notes centred around 20 Hz and are thought to be mating displays8,20 sung only by males5. Recent studies demonstrated that fin whale song is more complex than previously reported23,24. Song patterns can be characterized by two low-frequency note types (A and B), one high-frequency note type and different types of inter-note interval (INI) patterns23,24. The B note, often referred to as classic or 20 Hz note, is approximately 1 s long, has a peak frequency of 22–23 Hz20,24 and is down swept in frequency ranging from 42 to 14 Hz8,11,12,25. The A note, often referred to as backbeat, is slightly shorter, lower in frequency and less broadband with peak frequencies observed in the range 16–18 Hz3,14,22,23,24,26,27. The high-frequency note is a relatively short upsweep with higher frequency in the range 128–140 Hz and has only been observed in the North Atlantic6,20,24,28. It usually precedes B notes but has been reported also as a sole note type in several studies (see list provided in24).

Quasi-regular singlet patterns of c. 1 s long pulses with a constant INI between 7 and 40 s have most often been detected8,23,28,29,30,31, but songs with doublets (two alternating INIs23,24,30,32) or triplets (a pattern of three INIs, at least two of which are unique) are also reported30,32. Several studies indicate that INI values and patterns can be used for stock differentiation and have the potential to reveal the migration and distribution of fin whale populations28,30,31,32,33. However recent studies observed that individual fin whales switched song patterns in single song bouts, hence different song patterns are not necessarily indicative of different populations23,24,29. The mechanisms driving song variant use are not yet fully understood30. Understanding fin whale song in more detail is important for the monitoring of fin whale populations and understanding their behaviour24. Fin whales are sensitive to shipping34,35,36,37, so real-time information on their whereabouts is important for risk mitigation, especially in coastal zones. Hence (i) continuous (ii) real-time (iii) reliable (iv) long-timescale recording of vocalisations are important for the study of fin whale population change, their evolving social dynamics and their protection from hazards. Vocalisation data from ocean-deployed hydrophones honouring these four criteria are both physically challenging and expensive to acquire. Such monitoring efforts are currently operating, for example, along the Atlantic coasts of the US and Canada in order to study the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale (NARW). The real-time interactive ‘WhaleMap’ is provided online specifically tracking NARW38. The ‘Passive Acoustic Cetacean Map’39 provides information also for other whale species including fin whales and is currently based on data from four platform types: bottom-mounted moorings, surface buoys, drifting buoys and gliders. Onshore seismic recordings could possibly provide an additional affordable and reliable platform type for fin whale detections and song deconstruction.

In this feasibility study we analyse data subsets from pre-existing seismometer installations and show that fin whale vocalisations can be detected on near-coastal terrestrial seismic stations in various environments across the world, including: the NE Atlantic (Ireland, Iceland), the Mediterranean Sea (Monaco), the Pacific (Mexico) and the Southern Ocean (Antarctic Peninsula). Vocalising fin whales ensonify the sea floor at c. 20 Hz. Acoustic waves in the water couple to and travel in the solid earth as seismic waves40,41. For near-coastal vocalisations, we determine that these signals propagate for several kilometres inland and are readily detectable on land-based seismic ground vibration sensors, usually used for earthquake monitoring. 20 Hz is significantly above the maximum frequencies (e.g. 10 Hz) typically analysed on regional earthquake detection networks. Hence these signals are not usually detected due to automatic filter settings in standard data workflows, unless higher frequency filters are considered in local or hyperlocal seismic network applications. However, signals greater than 20 Hz are comfortably captured by most modern digital seismometers with typical sampling rates of 100 samples per second (i.e. 50 Hz Nyquist frequency) and can be clearly visible when not removed by automatic high-cut filters (Fig. 1). That fin whale song is detectable in terrestrial ground vibrations offers unexpected opportunities for monitoring, as delivering continuous real-time data streams is readily achievable from most terrestrial environments but challenging to attain from the ocean. Government agency, research-oriented seismic stations and individual citizen science Raspberry Shake seismometers42, all intended for earthquake detections and providing real-time open source data, are often located in coastal zones mirroring higher near-coastal global human population densities. Using publicly available instrument location data, we determine that at time of writing ~ 14% of permanent institutional seismic stations and ~ 17.5% of Raspberry Shake citizen seismometers are located within 3 km from a coast, representing a current total of about 1650 instruments worldwide (Supplementary Figure S1). Our demonstration herein that swaths of the coastal zone and human living spaces are regularly ensonified by fin whale song will likely come as a surprise to most people, and an inspiration to some. Citizen seismologists’ data offer dual opportunities for greater citizen engagement with the ocean and reliable long-term additional data on fin whale vocalisations, population migration patterns and social behaviour.

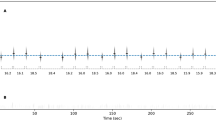

Onshore seismic recording of 30 min long fin whale song sequence. (a) Spectrogram and (b) corresponding time series of vertical seismic component HHZ, band-pass filtered between 18 and 23 Hz, from station IAP07 located on the southwest coast of Ireland near Baltimore, County Cork (see Fig. 2), equipped with a Trillium 120PA broadband seismometer. A 1024-point fast Fourier transform (FFT) with a Hanning window and 95% overlap was used to create the spectrogram.

In the next section we present a comparison between a fin whale vocalization recorded on the seafloor with both a hydrophone and a co-located ocean bottom seismometer (OBS). Then we present examples of recordings of fin whale notes made with onshore seismometers and demonstrate that they show all of the features typically seen on ocean deployed hydrophones. This is followed by examples of how data from two or three onshore stations can be used to locate near coastal singing fin whales. We conclude with a discussion of our findings, followed by a section presenting the methods used in this study.

Observations and results

Recordings of fin whale song by a hydrophone and Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS)

Fin whale songs travel as acoustic waves in the ocean but convert to more complex elastic waves as they pass through the sea floor and into the solid Earth. Hence the original note waveform is modified as it propagates as a seismic wave in the ground. We compare song acoustic recordings with their sister seismic data from an Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS) located on the seabed at 2750 m depth, in the NE Atlantic ~ 100 km northwest of Ireland (Figs. 2 and 3)43. The instrument has four channels: a hydrophone (HDH) and three components of seismic ground motion (vertical: HHZ and horizontals: HH1, HH2), see Appendix A in44 for details of the channel naming convention used in the seismological community. Visual inspection of the hydrophone data (Fig. 3a) shows a main pulse of approximately 1 s duration that down-sweeps from about 28.5–16.5 Hz. This agrees well with other reported fin whale note durations e.g. ~ 1 s8,20, 0.8 s13, 0.6 s12 and 0.5–1 s14 and down-sweep values ~ 25–17 Hz8, 28–18 Hz (maximum 32 Hz, minimum 14 Hz)11, 26–18 Hz12 and 42–18 Hz25. The weaker secondary pulse about 3 s after the main pulse is a multipath arrival that was first reflected at the seafloor and then the ocean surface23,40,45. This water column multiple is also visible in the recordings of the two horizontal seismic channels (Fig. 3c,d). Conversions, reflections and refractions of seismic waves in the solid subsurface complicate the latter part of the main seismic pulse and lengthen it, as observed in previous OBS studies40,41,45 and also in the only previous work presenting onshore seismic recordings of whale song46,47. Nonetheless this comparison demonstrates that the early portion of the ground-travelling seismic wave package recorded on the ocean floor compares well with the direct acoustic wave in the water column.

Map showing locations of fin whale sightings and seismic stations with fin whale song detections in Ireland. Sightings as reported by the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group (IWDG) for the years 2005 to 2023 are shown as circular markers, colour coded by month. Triangular markers show terrestrial seismic station locations where fin whale vocalisations were recorded. The extent of the main map is marked as dashed black rectangle in the inset with respect to the island of Ireland and the nearby continental shelf. The green square in the inset marks the location of Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS) and hydrophone installation ORK07. The map was generated with the software PyGMT version 0.10.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.830318648, using the IE GSI MI Bathymetry 10m Inshore dataset accessible at https://gsi.geodata.gov.ie/portal/home.

Fin whale note recorded on Ocean Bottom Seismometer ORK07. Top panels in subfigures show spectrograms and bottom panels show time series bandpass filtered between 15 and 30Hz. (a) Hydrophone channel HDH. (b) Vertical seismic component HHZ. (c, d) Horizontal seismic channels HH1 and HH2 respectively. A 112-point fast Fourier transform (FFT) with a Hanning window and 99% overlap was used to create the spectrograms.

Recordings of fin whale song by onshore seismometers

Previous studies demonstrated that vocalisations couple to the seabed close to their source, then travel in the solid earth as seismic body waves40,46, raising the prospect of widespread detection of near coastal fin whale song on land-based seismometers. By selecting appropriate frequency bands, in a non-exhaustive targeted manual search of data subsets from mainly pre-existing seismic stations, we detected fin whale song in seismic onshore recordings in Ireland, Iceland, Monaco, Mexico and Antarctica. The search process involves identifying regions and seasons where fin whales are frequently observed near the coast, obtaining seismic data from these areas and time periods, and scanning for signals characteristic of fin whale song (see Methods: Finding fin whale song in onshore seismic data). In Ireland, land-based fin whale seismic detections were distributed along the South coast in agreement with fin whale sightings reported by the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group (IWDG49) (Fig. 2). Station IAP07 near Baltimore in County Cork, as well as stations UGAL1, UGAL2 and UGAL4 near Galley Head in County Cork, are equipped with broadband seismometers while station RBB07 at the visitor centre of the Coppercoast Geopark in County Waterford and RB6F1 at the IAP07 site, incorporate citizen science seismometers (Supplementary Tables T1, T2). RB6F1 (Supplementary Fig. S2) was installed at the previous site of IAP07 following the detection of fin whale song in the IAP07 recordings. While we detected fin whale song on more than 60 days in one season at station IAP07 we did not analyse these detections in detail but present here a song example with particularly low background noise (Fig. 1). In order to verify qualitatively that this is indeed fin whale song we visually inspect note characteristics by examining the spectrogram and time series (see Methods: Finding fin whale song in onshore seismic data). In the example shown in Fig. 1 we observe notes with frequencies in the range 19–22 Hz in a singlet pattern over prolonged periods of 12–15 min, often called bouts, and an INI ranging from about 9–12 s. These values are within the range seen in several studies using ocean-deployed hydrophone data8,23,28,29,30,31 and corroborate that the observed terrestrial seismic signals are fin whale song. It is important to note that the values we observe and provide here are not a full representation of the song patterns recorded at terrestrial seismic station IAP07. Analysing such patterns is beyond the scope of this work. The ~ 2 min long periods of silence are most likely related to the singing whale surfacing to breathe8,12,50. At seismic stations RBB07 (Coppercoast Geopark, County Waterford, Ireland), MON (Oceanographic Institute, Monaco) and JUBA (Argentine Carlini Base, Antarctic peninsula) we observe song sequences that contain not only B but also A notes (see vertical arrows in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4) and doublet patterns. Such patterns have been reported previously on hydrophone data14,26,27 and are a current topic of research. They can possibly be used for stock differentiation30,32, though recent studies reported INI values changing over time23,28,29,30,31 and individual fin whales switching patterns in single song bouts23,24,29. The whale songs we detected at station JUBA at Carlini Base, Antarctic Peninsula, and station PBX at Cabo Banda near Ensanada, Mexico, notably cover much broader frequency ranges than other detections reported in this study. At JUBA the frequency range is 15–28 Hz and 14–34 Hz (Supplementary Figs. S4, S5), and at PBX it is 18–29 Hz (Supplementary Fig. S6). Similar frequency ranges have been reported in ocean deployed hydrophone studies, for example 14–34.5 Hz from Tonga51 and 14–32 Hz from Iceland11. One recording at JUBA features A notes with a low frequency of around 13 Hz (Supplementary Fig. S4). Another notable observation are relatively weak detections at citizen station R1B4E, located at Krýsuvík on the Reykjanes peninsula in Iceland (Supplementary Fig. S7). The station is located 5.5 km inland and these detections demonstrate that under favourable seismic noise conditions, fin whale song can be detected on-land, relatively far from the coast.

Fin whale song recorded with an onshore citizen science seismometer at the Copper Coast UNESCO Global Geopark on the southeast coast of Ireland, Bunmahon, County Waterford (see Fig. 2). (a) Spectrogram and (b) corresponding time series of vertical seismic component EHZ, band-pass filtered between 18 and 23 Hz, from station RBB07 equipped with a Raspberry Shake seismometer. Short vertical arrows mark A notes and long vertical arrows mark B notes. A 1024-point fast Fourier transform (FFT) with a Hanning window and 95% overlap was used to create the spectrogram.

Locating fin whales using onshore seismic stations

Seismic data are routinely employed to detect and locate impulsive disturbances, such as earthquakes and explosions. In the following we test the application of three seismic source location methods to fin whale notes. We use data from the three onshore seismic stations UGAL1, UGAL2 and UGAL4 positioned within several kilometres of each other on the southwest coast of Ireland near Galley Head in County Cork (see yellow markers in Fig. 2). We consider recordings from a time period when these stations simultaneously detected a fin whale song sequence (Fig. 5). The temporal pattern of note intervals and amplitudes shows that the signals received at the three stations originate from the same source. We determine the source location based on differences in signal back azimuth, arrival time and amplitude. In the following we compare results and relative precision of the three methods.

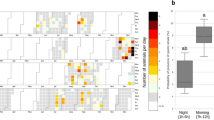

Fin whale note sequence of 5 min length recorded simultaneously with three onshore seismometers near Galley Head, County Cork, Ireland. (a) UGAL1, (b) UGAL2, and (c) UGAL4 time series of vertical seismic component HHZ, bandpass filtered between 18 and 23 Hz. The black rectangles between 150 and 200 s mark the three notes for which hodograms and location estimates are shown in Figs. 6 and 7 respectively. Note the different y-axis scale in the subfigures.

Determining back azimuth through polarisation analysis

The recordings of a three-component seismometer at the Earth’s surface can be used to distinguish different seismic wave types by their polarisations (see Methods: Polarisation analysis and polarisation filtering). Relatively fast first arrival compressional P-waves generate near-linear particle motion in the direction of wave propagation. Hence the horizontal polarisation of the first arriving segment of a seismic wave train is indicative of the back azimuth, i.e. the direction from which the seismic wave impinges on the recording seismometer, measured in degrees, clockwise from true North. Horizontal particle motion plots (hodograms) for the recordings of the three notes marked in Fig. 5 with a black rectangle, are shown in Fig. 6. The particle motion orientation of the earliest part of each note, ~ 0.25 s marked in black colour (also see Supplementary Fig. S8), is indicative of the back azimuth between the seismic station and the note source location. Assuming that the whale did not change location significantly while emitting the notes, we use the three back azimuths obtained for each station to provide back azimuth ranges as shown by the dashed coloured lines in Fig. 7. The horizontal polarisation analysis only provides an azimuth angle, it cannot distinguish between the two possible, opposite, directions from which the signal could impinge on the seismometer. However, the whale notes cannot originate from the land mass north of stations UGAL1 and UGAL2 (Fig. 7). In addition, three-dimensional polarisation analysis, i.e. also considering vertical seismic component data (HHZ), can resolve this ambiguity (see Methods: Polarisation analysis and polarisation filtering). The back azimuth ranges determined for the three seismic stations UGAL1, UGAL2 and UGAL4 intersect with an estimated precision of +/− 300 m in an area about 500 m from the shoreline (Fig. 7). The derived source area lies in a region with 20–35 m water depth in which fin whales have previously been sighted according to the IWDG sightings database (see circular markers on the map).

Horizontal hodograms for three consecutive fin whale notes recorded on seismic stations UGAL1, UGAL2 and UGAL4. (a, d, g) North–south seismic component (HHN) versus east–west seismic component (HHE) for the first 1 s of the first whale note in the black rectangle in Fig. 5. (b, e, h and c, f, i) show corresponding particle motions for the two subsequent notes in Fig. 5. The colour of each hodogram changes with time from black during the earliest part of each note, about 0.25 s long, to increasingly brighter colour, see time series shown in Supplementary Figure S8 for comparison. Coloured dashed lines represent back azimuth estimations, the resulting back azimuth range for each station is shown in Fig. 7. Vertical, north and east time series of the first note recorded at station UGAL2 are shown together with corresponding hodograms in Supplementary Figure S8.

Map of source area estimations for the fin whale notes in the black rectangles in Fig. 5. Dashed coloured lines present station back azimuth ranges derived from the horizontal hodograms shown in Fig. 6. White contours depict the calculated misfit contours for the arrival time location method with vp = 3700 m/s. Black bold lines show the misfit contours for the amplitude location method. Circular markers show fin whale sightings reported by the IWDG for the years 2005 to 2023, colour coded by month. Note, the fin whale identified through seismic detection here could not have been sighted as it occurred during the hours of darkness.

Arrival time based location

Assuming a uniform P-wave velocity vp, we compute the seismic travel times between each of the three seismic stations and cells on a regular grid with 50 m node spacing, covering the study area. The most likely source location for a recorded note is determined by identifying the cell with the smallest misfit sum between theoretical and observed times of arrival at the three stations (see Methods: Arrival time based location method). The resulting source location depends strongly on the chosen value for vp. The local geology consists of sandstone, siltstone and mudstone and in order to quantify the most appropriate vp we calculate source locations assuming vp values in a range typical for sandstone (1500–4300 m/s52). To determine arrival times, we employ both first arrival picking and picking maxima of vertical component seismogram envelopes, and find that using envelopes provides more consistent results. Using travel time differences averaged for each station over the three notes in the sequence we find similar relatively low minimum misfits when employing values of 3700, 4100 or 4300 m/s for the homogenous P-wave velocity of the grid. The resulting most likely source locations have a large variation of +/− 1500 m in the northwest-southeast direction, compare white contour lines in Fig. 7 with those in Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10. The back azimuth method has a better precision and agrees best with the solution for a vp value of 3700 m/s. Comparing the solution for individual notes using 3700 m/s with the average over the three notes we estimate the Arrival time based location precision to be about +/− 400 m in the northwest-southeast orientation and about +/− 200 m in the northeast-southwest orientation.

Amplitude based location

While the seismic detections at stations UGAL2 and UGAL4 are of similar amplitude, those at UGAL1 are about ten times weaker (Fig. 5). This indicates that the distance between station UGAL1 and the vocalizing whale is greater than for the other two stations. To quantify this observation, we employ a location method based on amplitude decay. The loss of seismic signal amplitude with distance is a consequence of both geometrical spreading and energy dissipation due to the anelasticity of the medium (see Methods: Amplitude based location method). Additionally, ground conditions at the individual station locations, known as site effects, also impact recorded seismic amplitudes. Hence, we apply site correction factors to the recordings, based on three quarry blasts that were recorded with sufficient energy in the frequency range of interest. The most likely vocalisation source location is determined through calculating the misfit E between theoretical and measured amplitude ratios for elements on a regular grid with 50 m node spacing, covering the study area. To calculate E using Eq. (5) (see Methods: Amplitude based location method), we use f = 20 Hz as the main frequency content of the whale notes and vp = 3700 m/s as determined above (see: Arrival time based location). We use vertical component seismogram envelope maxima of the P-wave of the fin whale notes to derive amplitude ratios, and average these over the three notes to reduce the influence of noise. The quality factor related to seismic wave attenuation Q is generally not well constrained but has a large impact on the calculated source location. Hence we repeat the misfit calculation across the grid for Q values in a range from 50 to 120 which is within the typical range for sandstone at shallow depth53. We observe a well-defined smallest minimum misfit for a Q value of 80 (see bold black contour lines in Fig. 7). The area with the lowest misfit lies about 750 m north of that calculated with arrival times (white contour lines) and about 500 m east from the intersection area of the three back azimuth ranges determined with the polarisation analysis (coloured dashed lines). The amplitude location method has a poor resolution in the northwest-southeast direction which we quantify by comparing the result for amplitude ratios averaged over the three notes (Fig. 7) with results obtained using the individual notes (Supplementary Figs. S11 to S13). The location precision is about +/− 1700 m in the northwest-southeast direction and about +/− 125 m in northeast-southwest direction.

Time dependent tracking

In the following we apply a hybrid of the amplitude and the back azimuth location methods to a longer song sequence with the aim of tracking whale song over time. We consider data from a 50 min long sequence detected with stations UGAL2 and UGAL4 (see Fig. 8a,c respectively). Although both stations are three-component, in principle this approach could be applied to data from a three-component and a single component instrument. The three-component station gives back azimuth information while amplitudes at both stations give range estimates. Data from station UGAL1 are not considered here because the signal to noise ratio at the station was too low for this time period. Amplitudes of the notes at UGAL2 are greatest at the beginning of the sequence and diminish towards the end. The amplitudes at UGAL4 are much lower at first but increase towards the sequence end. This indicates the whale notes were emitted closer to UGAL2 in the beginning but relatively closer to UGAL4 later in the sequence. While one could generate particle motion plots to establish the back azimuth and incidence angle of the individual notes, it is more convenient to apply polarisation filtering to the entire sequence. This type of filtering involves the computation of polarisation attributes of the particle motion as a function of time and then using those attributes to filter the time series so as to isolate the parts that correspond to a specific wave type (see Methods: Polarisation analysis and polarisation filtering). We apply filtering for a very high degree of polarisation and low ellipticity to isolate relatively fast P-waves which constitute the first arriving segment of the whale notes. Polarisation analysis of the two horizontal seismic component data cannot distinguish between the two possible, opposite, directions from which the signal could impinge on the seismometer. Horizontal polarisation analysis can only provide an azimuth angle in the range 0–180 degrees (Fig. 8b,d). However, by including the vertical component seismic data in the analysis the inclination of the polarisation ellipsoid with respect to vertical can be determined. Thus the back azimuth can be identified (see Methods: Polarisation analysis and polarisation filtering). Here the resulting azimuth time series for UGAL2 indicates the notes are first emitted from southeast of the station, due south after about 1000 s and then increasingly from the south-west (Fig. 8b). These azimuthal changes in time are in general agreement with the changing amplitude observation, indicating source migration from east to west. The azimuth time series for UGAL4 reveals seismic energy arriving with azimuths between 60 and 80 degrees throughout the sequence (Fig 8d). Closer inspection shows that a significant portion of this energy is attributable to background noise rather than whale notes, particularly strong at UGAL4 due to its headland location. Consequently, the UGAL4 data cannot provide reliable back azimuth information for the whale notes. However, the amplitudes of the whale note recordings at UGAL4 can still be accurately assessed (Fig. 8c). Therefore, source locations for the three note clusters marked in Fig. 8 can still be determined by combining the back azimuth analysis from UGAL2 with the amplitude based location method applied to the UGAL2 and UGAL4 data. The resulting map is presented in Supplementary Fig. S14.

Fin whale song sequence of 50 min length and corresponding azimuth time series obtained through polarisation filtering. (a) UGAL2 and (c) UGAL4 vertical seismic component HHZ time series, bandpass filtered between 18 and 23 Hz. (b) UGAL2 and (d) UGAL4 corresponding time series of the azimuth of the major axis of the polarisation ellipsoid obtained using polarisation filtering. Arrows indicate notes that were used for amplitude location analysis, numbered dashed ellipses mark note clusters for which location results are shown in Supplementary Fig. S14. Note that horizontal polarisation analysis only provides an azimuth angle, it cannot distinguish between the two possible, opposite, directions from which the signal could impinge on the seismometer. Other data (such as the location of the coast, or the inclination of the polarisation ellipsoid) can be used to make this distinction.

Discussion

We present fin whale song recordings obtained from an Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS) and co-located hydrophone in deep North Atlantic waters, about 100 km from the County Mayo coast in the northwest of Ireland. Comparing the characteristics of these OBS data to data from several onshore seismometers located on the south coast of Ireland, in Iceland, on the Mediterranean coast in Monaco, on the Pacific coast of Mexico and on the Antarctic peninsula, we determine that fin whale song can be detected on terrestrial near-coastal seismometers, in a variety of environments, globally. The comparison between hydrophone and seismic data from the OBS demonstrates that conversions in the solid subsurface complicate and lengthen the latter part of the seismic recording of a fin whale note. The early segment of the seismic wave train is not significantly distorted by such conversions and hence back azimuth analysis can be employed to extract directional information. In this feasibility study we inspect data from pre-existing publicly accessible seismic stations located onshore between 0.05 and 5.5 km from a coastline (Supplementary Table T1). While most of the stations are equipped with broadband seismometers, three stations are equipped with citizen science Raspberry Shake instruments. To our knowledge, this is the first report of fin whale song detections with this type of citizen science instrument, and greatly enhances opportunities for citizen engagement with the oceans. Here we also show that simultaneous recordings of whale notes on as few as two onshore seismometers can be used to track the movement of fin whales in the coastal zone. In order to obtain good signal-to-noise ratios we recommend that seismic installations that are targeted specifically at detecting whale song are located no further than 1 km from the coast to maximise recorded signal amplitudes. However, sites should not be located on narrow headlands, as wind and breaking ocean waves can significantly contribute to seismic noise within the relevant frequency range.

Data from fin whale songs captured by terrestrial seismic stations exhibit all of the main features typically seen on ocean-deployed hydrophones, such as rhythmic variability and a broad range of vocalisation spectral frequencies. Most of the seismometer recorded notes we present are within the 18–24 Hz frequency range, which agrees with the common range on hydroacoustic recordings. However, broader frequency ranges, as we observe in terrestrial recordings from the Antarctic Peninsula and Mexico, have also been documented in hydroacoustic studies carried out elsewhere (see: Recordings of fin whale song by onshore seismometers). This suggests that land-based recordings hold potential to contribute to detailed studies of fin whale song variability. Of particular interest is the discovery of detections on relatively low sensitivity and affordable citizen science Raspberry Shake seismometers, opening a new pathway for coastal communities to engage with the ocean. Furthermore, the near-coastal zone represents a region of increased human-induced hazard for fin whale populations including ship strikes34,35,36,37, noise pollution15,36,37 and entanglement in fishing gear2,20,22. Near-coastal seismometers potentially provide affordable and reliable early warning opportunities in detecting whale presence to help mitigate these hazards. Land-based seismic stations are relatively cheap to deploy, easy to maintain and continuous real-time data can readily be obtained. We envisage a new community of citizen scientists reaching into the ocean from the comfort of their own homes; contributing to rigorous science-driven investigations on how climate change and increasing human pressure on the marine environment impact the migration patterns, welfare and changing social patterns of fin whales. This study has already motivated citizens in Ireland and the IWDG to increase their capability for near-coastal fin whale monitoring by hosting citizen science seismometers. It is hoped that this work encourages communities globally to join this monitoring effort. Future additional work could include targeted installation of institutional seismometers in regions where near-coastal fin whale sightings are common, and applying machine learning techniques to detect whale song in the large catalogue of archived data from coastal seismic installations worldwide. Because some stations have been operating for decades it might be possible to determine long-term temporal changes in song characteristics and migration patterns, for example changes in the seasonal occurrence of fin whales. Assembling more fin whale song detections from onshore recorded seismic datasets could not only provide important information on fin whale vocalization and migration patterns but might also reveal previously unknown fin whale habitats. This study demonstrates that, globally, seismic data holds significant untapped potential for near-coastal fin whale monitoring.

Methods

Finding fin whale song in onshore seismic data

To find fin whale song in onshore seismic data, we first consult scientific literature (e.g.2) and sighting databases, such as the IWDG sightings database in Ireland, to identify regions and seasons where fin whales are frequently observed near the coast. Next, we locate publicly available seismic data recorded in these coastal regions, focusing on stations within 6 km of the coastline, ideally less than 3 km. This can be done using the interactive map for seismic stations, GMAP, hosted by the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) at https://ds.iris.edu/gmap. We then generate daily seismogram plots using the vertical component of the seismic data, filtered between 18 and 22 Hz (see for example Supplementary Fig. S15). We visually inspect these plots to identify characteristic repeating signals and select 30 min data subsets for further analysis. By plotting and examining spectrograms and time series of the chosen data, we confirm that the observed signals are fin whale notes. This confirmation involves analysing their spectral content, note length, song bout duration, and the time gaps between them8. Additionally, we identify potential patterns between A and B notes and look for typically lower amplitude pulses at the start and end of bouts8. While the amplitude variations are best observed in the time series plots, the other characteristics are better assessed through inspection of the spectrograms (see for example Fig. 1). Finally, we select data segments with a relatively high signal-to-noise ratio for more detailed analysis, such as locating the signal source.

Polarisation analysis and polarisation filtering

Three-component seismic data sample the trajectory of particle displacement. Because different seismic wave types are characterized by different polarisation shapes and directions, these characteristics can be used to distinguish different wave types in seismic data. Primary waves (P-waves) for example generate linear particle motion in the direction of propagation, and have a high degree of polarisation that is approximately linear54. Secondary waves (S-waves) also have linear particle motions, albeit perpendicular to wave propagation, and Rayleigh surface waves are characterised by elliptical particle motions. The polarisation of seismic motion can be visualized by plotting hodograms for two components of motion, see for example the horizontal hodograms shown in Fig. 6. The panels in the right column of Supplementary Fig. S8 present the three different particle motion plots for the first whale note in the black rectangle in Fig. 5b. The earlier part of the horizontal particle motion of the whale note, HHN versus HHE (north-south versus east-west seismic component), shows a linear polarisation in north-north-east to south-south-west orientation, see black part of the curve marking the first ~ 0.25 s of the note in Supplementary Fig. S8d. Similarly, the early wave motions in the two other particle motion plots, HHZ (vertical seismic component) versus HHN, and HHZ versus HHE, are also linearly polarized (Supplementary Figs. S8e, S8f). Because seismic waves arrive from underground at a seismometer located at the Earth’s surface the inclination of the early part of a HHZ-HHN hodogram indicates whether a seismic wave arrives from a northerly or southerly direction and the HHZ-HHE hodogram indicates whether the wave arrives from an easterly or westerly direction. For the UGAL2 example discussed here the HHZ-HHN hodogram shows that the seismic waves impinge from a southerly direction (Supplementary Fig. S8e), and the HHZ-HHE hodogram indicates a westerly impingement (Supplementary Fig. S8f). Overall this points to a south-westerly back azimuth for UGAL2, which is in agreement with the purely horizontal polarisation analysis shown in Fig. 7.

In order to analyse the polarisation of longer data sequences it is convenient to employ polarisation filtering rather than generating particle motion plots of individual notes. To employ polarisation filtering we perform polarisation analysis in sliding time windows using the complex analytic signal55 as implemented in the python package TwistPy56. This type of analysis determines several polarisation attributes including the degree of polarisation (DOP), ellipticity, incidence angle and azimuth of the major and minor axis of the polarisation ellipsoid. For this work we only consider the major axis of the polarisation ellipsoid. An example of polarisation analysis is shown in Supplementary Fig. S16 for the first whale note in the black rectangle in Fig. 5b. The first half-second of the note is characterized by high DOP, an ellipticity of 0.2–0.3, an inclination of about 75 degrees (measured from the vertical axis clockwise), and an azimuth of the major axis of the polarisation ellipsoid of about 30 degrees. The relatively low ellipticity of this wave packet suggests it is a P-wave, and the inclination is in agreement with a relatively shallow source. An example of polarisation filtering of these data is shown in Supplementary Fig. S17. We exclude all seismic data and polarisation attributes for times when the DOP is less than 0.95, ellipticity is over 0.3 and inclination is more than 80 degrees. By excluding large inclinations, we exclude surface waves and the restriction to small ellipticity ensures only waves with near linear polarisation are considered.

Arrival time based location method

We consider a regular 2D grid covering the study area and calculate, for each grid point, the theoretical travel time to each of the seismic stations located at distance x from the considered cell.

Then we calculate, for each grid point, the theoretical and the observed travel time differences between pairs of stations with index i and j. Calculating the misfit E for each grid point the most likely source location is identified by the grid point that yields the smallest misfit. In cases where the value for vp is not well constrained we repeat the search for a range of realistic values. The search result with the lowest misfit is assumed to provide the best location estimate. If there is no significant difference between the lowest observed misfit for different vp values it might be necessary to identify the best solution by comparison with another search method, e.g. the back azimuth method. Arrival times can be obtained from first arrival picking or picking maxima of seismogram envelopes. We found that picking envelopes gave more stable results when data are noisy.

Amplitude based location method

Consider the following expression for the decay of seismic body wave amplitude A over distance r in an attenuating medium57,58.

where A0 is the source amplitude and α = π f /Qvp.

The term 1/r in (Eq. 3) accounts for amplitude decrease caused by geometric spreading of seismic body waves and e−αr accounts for energy loss due to the anelasticity of the medium. In the expression for α the quantity f denotes signal frequency, Q the quality factor accounting for attenuation and vp the seismic P-wave velocity. The local attenuation and amplification characteristics at a seismic site, commonly known as site effects, can significantly influence the recorded seismic amplitude. Therefore, it is recommended to assess the site effects at considered seismic stations. This can be achieved by comparing the amplitude recordings of known distant seismic events, across multiple adjacent stations. If notable differences in the recorded amplitudes are observed, correction factors should be calculated and applied to account for the observed variations. In this study quarry blasts were used to determine site corrections.

In order to determine the source location of an individual whale note we consider amplitude ratios for pairs of stations with index i and j

We employ a regular 2D grid covering the study region and calculate, for each grid point, the theoretical and observed amplitude ratios, Aitheor/Ajtheor and Aiobs/Ajobs respectively. Calculating the misfit E for each grid point, the most likely source location is identified by the grid point that yields the smallest misfit58.

Data availability

The seismic and hydroacoustic data are available from public data repositories, see doi and International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks Web Service (FDSNWS) abbreviation for each station in Supplementary Table T1. The fin whale sighting catalogue for Ireland can be obtained from the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group (IWDG, https://iwdg.ie) on request.

Code availability

The polarisation analysis was carried out with the python package TwistPy56.

References

Cooke, J. G. Balaenoptera physalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e. T2478A50349982. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2478A50349982.en (2018) last accessed on 20 December 2024.

Edwards, E. F., Hall, C., Moore, T. J., Sheredy, C. & Redfern, J. V. Post-whaling era fin whale distribution. Mammal. Rev. 45, 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12048 (2015).

Weirathmueller, M. J., Wilcock, W. S. D. & Soule, D. C. Source levels of fin whale 20 Hz pulses measured in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133(2), 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4773277 (2013).

Richardson, W. J., Greene, C. R. Jr., Malme, C. I. & Thomson, D. H. Marine Mammals and Noise. Academic Press https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-02253-3 (1995).

Croll, D. A. et al. Only male fin whales sing loud songs. Nature 417(6891), 809 (2002).

Garcia, H. A. et al. Temporal–spatial, spectral, and source level distributions of fin whale vocalizations in the Norwegian Sea observed with a coherent hydrophone array. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 76(1), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsy127 (2018).

Širović, A., Hildebrand, J. A. & Wiggins, S. M. Blue and fin whale call source levels and propagation range in the Southern Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122(2), 1208–1215. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2749452 (2007).

Watkins, W. A., Tyack, P., Moore, K. E. & Bird, J. E. The 20-hz signals of finback whales (Balaenoptera physalus). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 82(6), 1901–1912 (1987).

Cummings, W. C. & Thompson, P. O. Underwater Sounds from the Blue Whale, Balaenoptera musculus. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 50(4B), 1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1912752 (1971).

Aguilar, A. Fin Whale. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-373553-9.00102-4 (2009).

Boisseau, O., Gillespie, D., Leaper, R. & Moscrop, A. Blue (Balaenoptera musculus) and Fin (B. physalus) whale vocalisations measured from northern latitudes of the Atlantic ocean. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 10(1), 23–30 (2008).

Gaspà Rebull, O., Díaz Cusí, J., Ruiz Fernández, M. & Gallart Muset, J. Tracking fin whale calls offshore the Galicia Margin, North East Atlantic Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120(4), 2077–2085. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2336751 (2006).

McDonald, M. A. & Fox, C. G. Passive acoustic methods applied to fin whale population density estimation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105(5), 2643–2651 (1999).

Pereira, A., Harris, D., Tyack, P. & Matias, L. Fin whale acoustic presence and song characteristics in seas to the southwest of Portugal. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 147(4), 2235–2249 (2020).

Ramesh, K., Berrow, S., Meade, R. & O’Brien, J. Habitat modelling on the potential impacts of shipping noise on fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in offshore Irish waters off the Porcupine ridge. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 1207 (2021).

Jiménez López, M. E., Palacios, D. M., Jaramillo Legorreta, A., Urbán, R. J. & Mate, B. R. Fin whale movements in the Gulf of California, Mexico, from satellite telemetry. PLoS ONE 14(1), e0209324. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209324 (2019).

Fujino, K. Immunogenetic and marking approaches to identifying subpopulations of the North Pacific whales. Sci. Rep. Whales Res. Institute 15, 85–142 (1960).

Tardy, C., Ody, D., Gimenez, O. & Planes, S. Abundance of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the north-western Mediterranean Sea, using photo-identification and microsatellite genotyping. Mar. Ecol. 44(e12737), 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/maec.12737 (2023).

Lydersen, C. et al. Autumn movements of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) from Svalbard, Norway, revealed by satellite tracking. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16966. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73996-z (2020).

Simon, M., Stafford, K. M., Beedholm, K., Lee, C. M. & Madsen, P. T. Singing behavior of fin whales in the Davis Strait with implications for mating, migration and foraging. J Acoust Soc Am. 128(5), 3200–3210. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3495946 (2010).

O’Brien, J., Berrow, S., McGrath, D. & Evans, P. Cetaceans in Irish waters: A review of recent research. Biol. Environ. Proc. Royal Irish Acad. 109(2), 63–88 (2009).

Blázquez, M. et al. Distribution models of baleen whale species in the Irish Exclusive Economic Zone to inform management and conservation. Mar. Environ. Res. 199, 106569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2024.106569 (2024).

Helble, T. A. et al. Fin whale song patterns shift over time in the central north pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 587110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.587110 (2020).

Guazzo, R. A., Stevenson, D. L., Edell, M. K., Gagnon, G. J. & Helble, T. A. A decade of change and stability for fin whale song in the North Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1278068. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1278068 (2024).

Thompson, P. O., Findley, L. T. & Vidal, O. 20-Hz pulses and other vocalizations of fin whales, Balaenoptera physalus, in the Gulf of California. Mexico. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 92(6), 3051–3057. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.404201 (1992).

Garcia, H. A. et al. Comparing performances of five distinct automatic classifiers for fin whale vocalizations in beamformed spectrograms of coherent hydrophone array. Remote Sens. 12, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12020326 (2020).

Constaratas, A. N., McDonald, M. A., Goetz, K. T. & Giorli, G. Fin whale acoustic populations present in New Zealand waters: Description of song types, occurrence and seasonality using passive acoustic monitoring. PLoS ONE 16(7), e0253737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253737 (2021).

Papale, E. et al. Occurrence and patterns of fin whale songs reveal alternative migration strategies in Svalbard Islands. Norway. Sci. Rep. 13, 4436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31665-x (2023).

Romagosa, M. et al. Fin whale song evolution in the North Atlantic. Elife 13, e83750. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.83750 (2024).

Wood, M. & Sirović, A. Characterization of fin whale song off the Western Antarctic Peninsula. PLoS ONE 17(3), e0264214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264214 (2022).

Delarue, J., Todd, S. K., Van Parijs, S. M. & Di Iorio, L. Geographic variation in Northwest Atlantic fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) song: Implications for stock structure assessment. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125(3), 1774–1782 (2009).

Širović, A. et al. Fin whale song variability in southern California and the Gulf of California. Sci Rep 7, 10126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09979-4 (2017).

Furumaki, S., Tsujii, K. & Mitani, Y. Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) song pattern in the southern Chukchi Sea. Polar Biol. 44(5), 1021–1027 (2021).

Laist, D. W., Knowlton, A. R., Mead, J. G., Collet, A. S. & Podesta, M. Collisions between ships and whales. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 17, 35–75 (2001).

Panigada, S. et al. Mediterranean fin whales at risk from fatal ship strikes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 52, 1287–1298 (2006).

Tort Castro, B., Prieto González, R., O’Callaghan, S. A., Dominguez Rein-Loring, P. & Degollada Bastos, E. Ship strike risk for fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) off the Garraf coast. Northwest Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 867287 (2022).

Espada, R. et al. Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus historical sightings and strandings, ship strikes, breeding areas and other threats in the mediterranean sea: A review (1624–2023). Environments 11, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11060104 (2024).

Johnson, H., Morrison, D. & Taggart, C. WhaleMap: A tool to collate and display whale survey results in near real-time. J. Open Source Softw. 6(62), 3094. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03094 (2021).

Passive Acoustic Cetacean Map. Woods Hole (MA): NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center v1.1.10 [last accessed 26.11.2024]. https://apps-nefsc.fisheries.noaa.gov/pacm (2024).

Kuna, V. M. & Nabelek, J. L. Seismic crustal imaging using fin whale songs. Science 371(6530), 731–735 (2021).

Soule, D. C. & Wilcock, W. S. D. Fin whale tracks recorded by a seismic network on the Juan de Fuca Ridge, Northeast Pacific Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133, 1751. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4774275 (2013).

Raspberry Shake, S.A. Raspberry Shake . International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. https://doi.org/10.7914/SN/AM (2016).

Le Pape, F. & Bean, C. J. Seasonal fluctuations in the secondary microseism wavefield recorded offshore Ireland, EGU General Assembly 2020 EGU2020-19154. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-19154 (2020).

Ahern, T., Casey, R., & Starovoit, O. Standard for the Exchange of Earthquake Data (SEED) Manual Version 2.4. International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. www.fdsn.org/pdf/SEEDManual_V2.4.pdf (2012)

Iwase, R. Fin whale vocalizations observed with ocean bottom seismometers of cabled observatories off east Japan Pacific Ocean. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 54, 07HG03. https://doi.org/10.7567/JJAP.54.07HG03 (2015).

Plourde, A. P. & Nedimovic, M. R. Monitoring fin and blue whales in the lower St. Lawrence seaway with onshore seismometers. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 8(4), 551–563 (2022).

Goblot, E. et al. Spatiotemporal variability of fin whale and blue whale calls detected by land seismometers along the lower St. Lawrence seaway. Seismica 3(2), 1153. https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v3i2.1153 (2024).

Tian, D., Uieda, L., Leong, W.J., Schlitzer, W., Froehlich, Y, Grund, M., Jones, M., Toney, L., Yao, J., Magen, Y., Jing-Hui, T., Materna, K., Belem, A., Newton, T., Anant, A., Ziebarth, M., Quinn, J. & Wessel, P. Pygmt: A python interface for the generic mapping tools (v0.10.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8303186 (2023).

Whooley, P., Berrow, S. & Barnes, C. Photo-identification of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus L.) off the south coast of Ireland. Marine Biodiversity Records 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755267210001119 (2011).

Dréo, R., Bouffaut, L., Leroy, E., Barruol, G. & Samaran, F. Baleen Whale distribution and seasonal occurrence Revealed by an ocean bottom seismometer network in The Western Indian Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part II 161, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.04.005 (2019).

Brodie, D. C. & Dunn, R. A. Low frequency baleen whale calls detected on ocean-bottom seismometers in the Lau basin, southwest Pacific Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 137(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4904556 (2015).

Press, F. Seismic Velocities. In S.P. Clark, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of Physical Constants. pp. 195–218. (Geological Society of America 1966)

Schön, J. H. Physical Properties of Rocks, A Workbook Vol. 8 (Elsevier, 2011).

Samson, J. C. & Olson, J. V. Some comments on the descriptions of the polarization states of waves. Geophys. J. Int. 61(1), 115–129 (1980).

Vidale, J. E. Complex polarization analysis of particle motion. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 76(5), 1393–1405 (1986).

Sollberger, D. solldavid/TwistPy: TwistPy - First release (v0.0.1-beta). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8124030 (2023).

Battaglia, J. & Aki, K. Location of seismic events and eruptive fissures on the Piton de la Fournaise volcano using seismic amplitudes. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2364 (2003).

Li, K. L. et al. Seismic tremor reveals slow fracture propagation prior to the 2018 eruption at Sierra Negra volcano, Galápagos. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 586, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2022.117533 (2018).

Reilly, L. “QuakeShake” - A New Citizen Earthquake Outreach Programme in Ireland. EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, 14-19 Apr 2024, EGU24-7951. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu24-7951 (2024).

Wessel, P. et al. The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20(11), 5556–5564. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008515 (2019).

Beyreuther, M. et al. Obspy: A python toolbox for seismology. Seismol. Res. Lett. 81(3), 530–533. https://doi.org/10.1785/gssrl.81.3.530 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank David Craig, James Grannell, Paddy Smith, Louise Collins, Laura Reilly, Clare Horan, Florian Le Pape and Colin Hogg for technical support. We thank Simon Berrow and Stephen Comerford from the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group (IWDG) for providing the fin whale sightings database. We also thank private landowners in Ireland for hosting seismometers IAP07, RB6F1, UGAL1 and UGAL2. Many thanks to the Commissioners of Irish Lights for hosting station UGAL4 and to the visitor centre of the Copper Coast UNESCO Global Geopark for hosting station RBB07 which is operated as part of the citizen science initiative QuakeShake59. We also thank the operators of the seismic networks with code AI, AM, BC and FR (Supplementary Table T1). Maps were generated using PyGMT version 0.10.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.83031865 based on Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) version 660. Other figures were created using Obspy61. The IE GSI MI Bathymetry 10m Inshore dataset used for the maps is accessible at https://gsi.geodata.gov.ie/portal/home. This publication contains Irish Public Sector Data (Geological Survey Ireland & Marine Institute) licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this work. C.J.B. and M.M. conceived the study. M.M. analysed data and generated figures. Both authors interpreted the results and wrote, edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Möllhoff, M., Bean, C.J. Fin whale song recordings by onshore seismometers open new horizons for cetacean coastal monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 13475 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97638-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97638-4