Abstract

Rapid and reliable diagnostic tests for tuberculous meningitis (TBM) in children remain limited. This study evaluated the performance of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Ultra), an improved version of Xpert MTB/RIF (Xpert), for detecting TBM in children using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Children (0–14 years) presumptive of TBM were enrolled prospectively from three tertiary level hospitals in Dhaka, Bangladesh, from December 2019 to January 2022. CSF was tested by Ultra, Xpert, Lowenstein–Jensen (L–J) culture, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) microscopy. Diagnostic performance was assessed against clinical case definitions, composite microbiological reference standard (CMRS), and L–J culture. Of 187 children, Ultra detected TBM in 23.4% of cases, significantly higher than the 9.1% detected by Xpert (p < 0.001). Compared to the clinical case definition of probable and definite TBM, Ultra exhibited a sensitivity of 88% (44/50), markedly outperforming Xpert (34%, 17/50) and L-J culture (30%, 15/50) (p < 0.001). Against the CMRS, Ultra’s sensitivity was 100% (44/44), compared to Xpert (38.6%, 17/44) and L-J culture (34.1%, 15/44) (p < 0.001). AFB microscopy showed very low sensitivity (2.3%, 1/44). Negative predictive values for both clinical case definition and CMRS were higher for Ultra (95.8–100%) than Xpert (80.6–84.1%) and L–J culture (79.7–83.1%) (p < 0.001). Compared to gold standard L–J culture, Ultra’s sensitivity (100%, 15/15) was also higher than Xpert (93.3%, 14/15) (p = 0.316), with specificities of 83.1% (143/172) and 98.3% (169/172), respectively. Ultra detected 26 TBM cases missed by other tests, with most (84.6%) in the ‘trace detected’ category. Due to the high performance, Ultra can be used widely at health care settings of high TB burden countries like Bangladesh for rapid and accurate diagnosis of paediatric TBM using CSF samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is one of the most deadliest infectious diseases worldwide1. Tuberculous meningitis (TBM), is a severe form of extra-pulmonary TB that occurs when the bacteria infect the meninges of the brain and spinal cord2. TBM results in mortality or severe disability in over 50% of the affected individuals, primarily due to diagnostic delays and difficulties3,4. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are essential for managing TBM effectively and improving patient outcomes5,6. Diagnosing TBM in children is particularly challenging because symptoms often cannot be differentiated with other meningitis, and challenges such as low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volumes for laboratory investigations, difficulty in obtaining detailed history, and the paucibacillary nature of TB in children further complicate the process4. Current diagnostic methods, such as smear microscopy, offer rapid results but have a low sensitivity (< 15%) for CSF samples3. Mycobacterial culture, while more sensitive (50–60%), is often too slow to be clinically useful as treatment is urgently needed for TBM cases3. The clinical diagnosis of TBM is complicated by its nonspecific presentation, which can mimic other forms of meningitis4. Consequently, in the absence of microbiological confirmation, clinicians often rely on a combination of clinical findings, laboratory results, and neuroimaging to make a probable diagnosis4,7.

Xpert MTB/RIF assay (Xpert), a modern cartridge-based diagnostic tool capable of detecting M. tuberculosis and its resistance to rifampicin (RIF) directly from clinical samples in under two hours8,9,10,11. The World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed Xpert as a point-of-care test for pulmonary TB in 2010 and for extrapulmonary TB in 201312. To enhance the detection of paucibacillary TB, Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Ultra) was developed, boasting a lower limit of detection (15.6 colony-forming units [CFU] per ml) compared to the original Xpert assay (131 CFU/ml)13. Recently, WHO recommended replacing Xpert cartridges with Ultra in 2017 due to its increased sensitivity for detection of TB patients with very low bacterial burden14.

Several studies in adults have shown that Ultra exhibits higher sensitivities than Xpert (47.2–95% versus 39.6–65.8%) when compared to microbiological reference standards or clinical assessments for diagnosing TBM15,16,17. However, the diagnostic performance of Ultra versus Xpert for TBM in children remains largely unexplored, with only one study from India reporting overall low sensitivity—50% for Ultra compared to 18% for Xpert18. In this study, we evaluated the performance of Ultra and Xpert for detecting TBM in children using CSF samples collected from clinical settings in Bangladesh with a high prevalence of TB.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Presumptive TBM patients across the country are typically referred to tertiary hospitals due to the limited availability of diagnostic facilities in other healthcare centers. From December 2019 to January 2022, children (< 15 years) suspected of TBM were prospectively enrolled from three major tertiary hospitals in Dhaka: Dhaka Medical College & Hospital (DMCH), Shahid Suhrawardy Medical College & Hospital (ShSMCH), and the National Institute of Neurosciences & Hospital (NINS). DMCH and ShSMCH are among the largest public hospitals in Bangladesh, handling a high volume of patients and receiving referrals from across the country. Whereas, NINS located in Dhaka’s healthcare hub, is the only government-run tertiary neuroscience center in Bangladesh, providing specialized outpatient services to thousands of patients daily.

Children were included in the study if they showed one or more signs and symptoms of meningitis, such as headache, irritability, vomiting, fever, neck stiffness, convulsions, focal neurological deficits, altered consciousness, or lethargy. Additionally, participants were required to exhibit one or more systemic symptoms indicative of tuberculosis, such as poor weight gain, night sweats, or a persistent cough lasting more than two weeks, and a history of recent close contact with tuberculosis patients7,19. Detailed medical histories were collected for all enrolled children. Each participant was evaluated and scored using the International Consensus on Case Definition for TBM, and subsequently classified as definite, probable, possible, or not TBM7. Details of clinical case definition for TBM has been provided in the Supplementary Table S1 and S2). The study was conducted in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) guideline, a comprehensive checklist designed to ensure transparent, complete, and standardized reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies20. Patients were excluded from the study if lumber puncture was contraindicated, CSF volume was less than 2.0 ml, refused to provide informed consent, or already started anti-TB treatment. A total of 187 presumptive TBM children were enrolled which was required to detect the sensitivity of 95% at 10% level of precision when the prevalence of TBM was expected to be 10.8% among presumptive children (based on our laboratory evidence on 12 months data of 2018, as there was no data regarding the prevalence of TBM in Bangladesh) and 10% loss to follow up/incomplete data.

Specimen collection and laboratory procedures

The CSF specimens were collected from the presumptive TBM children by the hospital physicians as per their regular standard procedure. For this study purpose, at least 2.0 ml of CSF was collected and transported to Mycobacteriology Laboratory of International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr, b) following standard procedure maintaining the cold chain. CSF volume of more than 2.0 ml was centrifuged at 3000 g for 20 min to concentrate bacilli. Supernatant was discarded using micropipette to leave a minimum volume of 2.0 ml which was resuspended for use in Xpert, Ultra, smear microscopy, and culture. Whereas, CSF volume of around 2.0 ml was not centrifuged. An aliquot of 0.7 ml of CSF was cryopreserved at − 80 °C for future use in case of repeat testing. Smear microscopy and conventional culture on solid Lowenstein-Jensen (L-J) media were performed as described elsewhere21.

Xpert and ultra assay

The testing procedure for both Xpert and Ultra assays were same, except for the cartridges, and the test was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction with few modifications. In brief, 1 ml of CSF was diluted with 1 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH: 7.4). Manufacturer’s provided sample reagent (SR) was added to the diluted CSF in 1:1 ratio, manually agitated twice during a 15 min of incubation period at room temperature and then 2.0 ml was transferred to both Xpert and Ultra test cartridges to run into the GeneXpert platform and automatically generated results were recorded. According to the manufacturer, the Xpert and Ultra assays were optimized for detecting pulmonary TB using sputum samples. However, their application for diagnosing extrapulmonary TB across various specimen types has been extensively investigated by researchers worldwide. Based on promising findings, the WHO recently recommended that in adults and children presenting with signs and symptoms of TB meningitis, Xpert or Ultra should be used as the initial diagnostic test rather than smear microscopy or culture22. Unlike sputum samples, the processing of extrapulmonary specimens for Xpert or Ultra testing varies. For CSF, a 1:1 sample-to-buffer ratio has already been optimized in previous studies23, which we followed in our study.

Smear microscopy, culture and drug susceptibility testing

Both AFB microscopy and culture were performed on unprocessed CSF specimen. For AFB microscopy, a loopful of CSF was smeared on glass slide and stained with Ziehl-Neelsen staining following standard procedure. The CSF specimen was inoculated on two L-J media slants to improve the isolation of mycobacterial species, and provide a backup in case of contamination. The slants were incubated at 37 °C up to 8 weeks for which growth of visible mycobacterial colony as well as contamination was examined weekly21. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) was performed by proportion susceptibility method in L-J media against RIF for the culture positive isolates according to the WHO recommended critical concentration at 40.0 µg/ml21. After getting sufficient culture growth, a standard suspension of M. tuberculosis isolates was inoculated onto drug containing L-J media as well as drug free L-J media as control. Isolates were considered resistant to a particular concentration of drug when > 1% colonies were observed on the drug-containing media compared to the drug-free medium.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical information as well as laboratory results were analyzed by SPSS version 20.0. Continuous data were analyzed using independent t-test and categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The significance level was measured by p-value < 0.05. The diagnostic performance of all tests was evaluated by comparing its sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) against the uniform clinical case definition of TBM, composite microbiological reference standard (CMRS), and L-J culture. Here, CMRS is defined as M. tuberculosis complex positive in any of the four bacteriological methods (Xpert, Ultra, smear microscopy, and culture).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 187 presumptive TBM children have been given in Table 1. Among the patients, 102 (54.5%) were male. The mean age of the patients was 6.1 (± 4.7 SD) years, with the majority falling in the age group of below 5 years (46.0%). The majority of patients (71.1%) lived in rural areas. Only 4.3% of the patients had previous exposure to TB patients and 1.1% was previously diagnosed and treated for TB. Variables including female sex and other clinical symptoms like evening rise of temperature, headache, vomiting, and neck stiffness were significantly higher among children who were positive for TBM by CMRS than those who were negative (Table 1). The average CSF volume used for mycobacterial testing was 2.5 ml, ranging from 2 to 7 ml. CSF was clear in 172 (92%) participants, and turbid for the remaining 15 (8%) participants. Lack of white blood cell pleocytosis, CSF lymphocyte percentage, and CSF total protein differed significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

All 187 enrolled presumptive TBM children underwent comprehensive laboratory investigations and clinical evaluations. CSF specimens from all participants yielded final valid results through Ultra, Xpert, culture, and microscopy. Among them, 44 (23.5%) tested positive for M. tuberculosis by Ultra, 17 (9.1%) by Xpert, 15 (8.0%) by culture, and 1 (0.5%) by AFB microscopy (Fig. 1). A total of 44 (23.5%) children were found positive for TBM by the CMRS. Based on the uniform clinical case definition of TBM, finally 6 (3.2%) were classified as probable, 74 (39.6%) as possible, and 63 (23.5%) as not TBM. Definite TBM was categorized for 44 participants as they were found to be positive by any one of the four microbiological methods tested i.e. CMRS (Fig. 1). When the microbiological test results were excluded, uniform clinical case definition categorized 36 (19.3%), 85 (45.4%), and 66 (35.3%) children as Probable, Possible, and Not TBM. The distribution of results of Ultra and Xpert among these clinical categories have been shown in the Supplementary Table S3.

A total of 61 children were treated for TBM with anti-TB drugs. Among the children diagnosed with TBM and tested positive using Ultra, 93.2% (41 out of 44) received TB treatment from physicians (Fig. 1). However, three children identified as ‘Trace Detected’ by Ultra did not receive TB treatment from their physicians. We monitored these patients for 12 months following their TBM diagnosis, and their health remained stable throughout the follow up period. Results of Ultra and Xpert on CSF samples of children along with their clinical categories who received anti-TB treatment have been shown in Supplementary Table S4.

A flow diagram illustrating the enrolment, investigation outcomes, and treatment of children (under 15 years old) with presumptive tuberculous meningitis admitted to three selected tertiary hospitals in Dhaka, Bangladesh (n = 187). CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; Xpert, Xpert MTB/RIF; Ultra, Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra; L–J, Lowenstein–Jensen; AFB, acid fast bacilli.

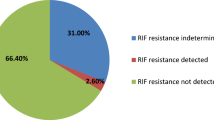

The detection rate of M. tuberculosis in CSF by Ultra (23.4%) was significantly higher than Xpert (9.1%) (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Out of the 44 Ultra positive CSF, the bacilli burden as determined by the automated GeneXpert system was ‘Medium’ for 1 (2.3%), ‘Low’ for 13 (29.5%), ‘Very Low’ for 8 (18.2%), and ‘Trace Detected’ for 22 (50%). None of the samples were found to have ‘High’ bacillary load (Table 2). Notably, all samples with ‘Trace Detected’ category by Ultra were found negative in other three methods: Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy. No RIF resistant patient was identified by either Ultra or Xpert. However, all 22 ‘Trace Detected’ patients had indeterminate results for RIF resistance. Additionally, when drug susceptibility testing was conducted using solid media, all 15 culture positive isolates were found to be RIF sensitive.

In the analysis of Ultra results for different age groups of children, we found that the patients with ‘Trace Detected’ category (having lowest bacillary burden) were more common than the ‘MTB Detected’ category (having bacillary load higher than ‘Trace Detected’ category) among children aged 0–4 years (p = 0.060). On the other hand, patients with ‘MTB Detected’ category with higher bacillary loads were more common among older children aged 10–14 years (p = 0.077) (Table 3).

Figure 2 shows the Venn diagram of TBM positive patients detected by different methods. Ultra was positive in 44, of whom Xpert was also positive in 17 and L-J culture in 15. AFB microscopy was found positive in one CSF sample which was also positive by other three methods. 26 patients tested positive for M. tuberculosis in CSF sample by Ultra alone, but were negative by other three methods. Among these 26 patients, 22 (84.6%) were ’Trace Detected’ category. By CMRS, total 44 patients were found positive for TBM, and 143 negatives for TBM (negative by all four methods).

Venn diagram depicting the bacteriological confirmation using various methods on CSF samples from children with presumptive tuberculous meningitis (n = 187). A total 44 participants were confirmed as tuberculous meningitis microbiologically by either Ultra, Xpert, L-J culture, or AFB microscopy. There were 143 participants tested negative for M. tuberculosis complex by all methods. Xpert, Xpert MTB/RIF; Ultra, Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra; L–J, Lowenstein–Jensen; AFB, acid fast bacilli.

Diagnostic performance of Ultra, Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy was evaluated against the uniform clinical case definition and CMRS. When compared with the uniform clinical case definition of probable or definite TBM, the sensitivities of Ultra, Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy were 88.0% (95% CI: 75.7–95.5), 34.0% (21.2–48.8), 30.0% (17.9–44.6), and 2.0% (0.05–10.7), respectively, whereas, the negative predictive values (NPV) were 95.8% (91.5–98.0), 80.6% (77.3–83.5), 79.7% (76.6–82.4), and 73.7% (72.9–74.4), respectively (Table 4). When we included the possible TBM in the clinical case definition, and compared against the possible, probable or definite TBM, the sensitivity of all tests diminished. The sensitivities of Ultra, Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy were 35.5% (95% CI: 27.1–44.6), 13.7% (8.2–21.0), 12.1% (6.9–19.2), and 0.81% (0.02–4.4), respectively, whereas the NPV were 44.1% (40.9–47.3), 37.1% (35.4–38.7), 36.6% (35.1–38.2), and 33.9% (33.5–34.2), respectively. For both clinical reference standards, the sensitivities of Ultra were significantly higher than Xpert, and as well as L-J culture and AFB microscopy (p < 0.001). In order to address the bias of incorporating Ultra as an index test into the classification of clinical case definitions and CMRS, the results of Ultra were excluded to determine if its performance differed significantly from the existing analysis. The sensitivities of Ultra still remained higher but the specificity reduced than Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy when compared clinically and CMRS (Supplementary Table S5).

When compared against the CMRS, the sensitivity of Ultra was 100% (92.0-100), which was significantly higher than Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy having sensitivities of 38.6% (24.4–54.5), 34.1% (20.5–49.9), and 2.3% (0.06-12.0), respectively (p < 0.001) (Table 4). The NPV of Ultra, Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy were 100% (97.5–100), 84.1% (80.7–87.0), 83.1% (80.0-85.9), and 76.9% (76.1–77.7), respectively. The specificities for all methods were 100% (97.5–100) when compared against the uniform clinical case definition, or CMRS.

There were total 15 CSF samples that became positive by the gold standard L-J culture. Compared to the gold standard culture, the sensitivities of Ultra, Xpert, and AFB microscopy were 100% (78.2–100), 93.3% (68.1–99.8), and 6.7% (0.2–32.0), respectively, whereas, the specificities were 83.1% (76.7–88.4), 98.3% (95.0-99.6), and 100.0% (97.9–100), respectively (Table 4). All 15 culture positive isolates were found RIF sensitive by DST using standard proportion method in L-J media. Both Ultra and Xpert showed 100% concordant result (RIF sensitive) with L-J DST for detection of RIF susceptibility.

The diagnostic performance of all methods was also evaluated among different age groups of children (Supplementary file, Table S6). When compared with the clinical case definition of ‘probable and definite’ TBM, the sensitivity of Ultra was found to be significantly higher among the older group of children (100%) (aged between 10 and 14 years) than the younger group (79.0% for 0–4 years, and 83.3% for 4–9 years) (p < 0.05). However, when compared with the CMRS or culture, the sensitivity of Ultra was the same (100%) for all age groups of children.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the performance of Ultra, alongside its predecessor, Xpert, as well as AFB microscopy and culture for detecting TBM in children. All tests were performed on the same CSF sample, allowing for an accurate assessment of each method’s performance. The most notable finding was the higher sensitivity of Ultra than Xpert for detection of M. tuberculosis in CSF of children, when compared with either uniform clinical case definition or CMRS. When compared clinically, considering probable and definite TBM as reference standard, the sensitivity of Ultra was more than double (88%) than Xpert (34%). Even with the inclusion of participants with possible TBM in the clinical reference standard, the overall sensitivity of both Ultra and Xpert decreased, but Ultra still exhibited more than double the sensitivity (35.3%) compared to Xpert (13.7%). The overall reduced sensitivity may stem from the nonspecific nature of the ‘possible TBM’ classification within the uniform clinical case definition for TBM diagnosis, a phenomenon previously observed in the HIV infected population for adults16 which likely be also applicable to the presumptive TBM patients in our paediatric study.

Ultra showed a sensitivity of 100% when compared with the CMRS. This was significantly higher than Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy which had sensitivities of 38.6%, 34.1%, and 2.3%, respectively. The higher sensitivity of Ultra is due to its capacity to detect TBM even in patients with extremely low or trace levels of bacteria in CSF, surpassing the capabilities of Xpert. Consequently, Ultra detected the highest number of positive samples among the other tests within the CMRS, achieving 100% sensitivity. When compared with the L-J culture alone, Ultra also had a higher sensitivity of 100%, compared to 93.3% for Xpert, indicating better detection of the disease. Prior research has consistently shown that Ultra outperforms Xpert in detecting TBM in CSF among HIV co-infected adults, as assessed against clinical or CMRS or cultures15,16,17. However, studies on the performance of Ultra in CSF among children are limited. A recent study in India involving children reported overall lower sensitivities for both Ultra and Xpert (50% versus 18%) compared to our findings. Despite this, Ultra continued to demonstrate superior sensitivity over Xpert when assessed against clinical criteria or CMRS18.

In this study, half of the positive Ultra results (22 of 44, 50%) were in the ‘Trace Detected’ category which is usually below the detection limit of Xpert. These 22 trace-positive samples were identified only by Ultra and not by other methods such as Xpert, L-J culture, or microscopy. Ultra has approximately eight times better detection capability for M. tuberculosis, with a detection limit of 15.6 CFU per ml of sputum sample, compared to Xpert which has 131 CFU/ml13. This likely explains the improved sensitivity of Ultra over the Xpert. While culture has a detection limit of 10 CFU/ml of sputum, it can only detect live bacilli. The ability of Ultra to detect non-viable bacilli may also contribute to its enhanced sensitivity compared to culture15. As expected, the sensitivity of AFB microscopy was found significantly lower compared to the reference standard of culture or CMRS. In this study, only one TBM case was found positive by AFB microscopy, and therefore, the assay was not suitable for the diagnosis of TBM among children. Specificity (and the positive predictive value) was 100% for all index tests as they were included in the composite clinical or microbiological reference standards. It is well established that Ultra has higher sensitivity than Xpert for pulmonary tuberculosis detection in sputum samples24. However, its performance in detecting TBM using CSF samples, particularly in children, remains less well-defined22. Given that TBM is a paucibacillary disease, culture—the gold standard—often has low sensitivity and is frequently unable to confirm the cases15. As a result, CMRS or clinical reference standards are commonly used to assess the diagnostic performance of TB tests, including Ultra25. We acknowledge that when the composite reference standard includes the index test, by definition false positives cannot be identified, leading to an artificially inflated specificity of 100%—a recognized limitation of the approach. To minimize this bias, we excluded Ultra’s results from the composite reference standards (Supplementary Table S5). Despite this adjustment, Ultra still demonstrated higher sensitivity but lower specificity than Xpert. When compared with L-J culture, the specificity of Ultra was lower at 83.1%, than to 98.3% for Xpert. It is important to note that lower specificity does not necessarily mean a higher likelihood of false positivity. Rather, it indicates that Ultra is capable of detecting a small number of bacilli or even the fragments of nucleic acid that were not detected by culture13,15,16.

Although the reason is not clearly understood, the CSF samples containing the lowest bacterial burden (‘Trace Detected’ category) as determined by Ultra, were more common among young children aged 0–4 years, which is in agreement with the findings of a previous study conducted among children in India18. This finding implies that Ultra could be more useful in detecting the TBM among the youngest children otherwise they remained undetected if tested by Xpert or culture.

Recently, WHO recommended to use of Ultra as an initial test on CSF samples of children showing signs and symptoms of TBM22. However, there is a lack of data on treatment initiation decisions for children diagnosed with ‘Trace Detected’ category in CSF samples. In a WHO technical expert consultation meeting, it was suggested to consider the ‘Trace Detected’ call for children and extrapulmonary specimens as true positive for clinical decision-making14. In our study, all Ultra positive children received anti-TB treatment, except for three with ‘Trace Detected’ category. According to the uniform clinical case definition7, these three children were categorized as ‘possible TBM’, but not treated for TB by the hospital physicians. After monthly follow up for one year, the health condition of these patients improved, though one patient continued to have neurological symptoms. The fact that these three Ultra positive children remained stable without treatment raises concerns about potential false positive results. Ultra’s high sensitivity allows it to detect even minute amount of M. tuberculosis DNA, including dead or non-viable bacteria. In cases of prior TB exposure or incipient TB, residual bacterial DNA could potentially trigger a positive result without indicating active disease26. However, in our study, none of the children with ‘Trace Detected’ results had a previous history of TB treatment, and we were unable to determine their incipient TB status. Therefore, the exact reason for their Ultra positivity remains inconclusive. Additionally, despite adherence to the standard laboratory protocols, the possibility of cross-contamination cannot be entirely ruled out. In contrast, among 19 children with ‘Trace Detected’ category, who received anti-TB treatment, the majority (89.5%, 17/19) showed improvement, as confirmed by one-year follow up. Future research should be conducted to systematically examine how children with presumptive TBM progress clinically and respond to treatment, with and without Trace calls. Evaluating clinical outcomes could provide better understanding into the usefulness of Ultra’s ‘Trace Detected’ call on CSF specimens for diagnosing TBM in children.

Only 17% (1/6) of children with probable TBM and 20% (15/74) of children with possible TBM were treated for TB without microbiological evidence, based on the clinical judgement of hospital physicians. Moreover, 4 children who were categorized as not TBM by clinical definition and tested microbiologically negative also received anti-TB treatment by the hospital physicians. This suggests that physicians relied on their won clinical judgment rather than strictly adhering to the standardized clinical case definition or microbiological results. Given that TBM is a life-threatening disease, physicians might have opted for treatment based on a clinical suspicion. However, the absence of microbiological confirmation and failure to meet the clinical definition raise the possibility that these cases were not true TBM, and therefore, might have been exposed to unnecessary TB drugs. These findings highlight the need to assess the uniform TBM case definition for its practical application in different settings, as its effectiveness may vary based on population, geography, and age group27,28. Further follow-up and analysis of treatment outcomes in such cases could provide valuable insights into whether the clinical criteria for diagnosing TBM led to appropriate or excessive treatment.

Several clinical characteristics observed in this study like evening rise of temperature, headache, vomiting, neck stiffness, CSF lymphocyte percentage, total protein content, and white blood cell count have been found significantly higher among TBM positive children than negative confirmed by CMRS. Future systematic case control cohort studies would help to validate which clinical findings or bio-markers can be considered as pathognomonic features between TBM and other meningitis patients. Bangladesh has a low HIV prevalence, with a rate of less than 0.01% in the general population29. As a result, routine HIV testing is not commonly conducted, and data on HIV status were unavailable for the presumptive TBM children in this study. Consequently, we were unable to assess any correlation between TBM positivity and HIV status.

This study has several limitations. First, we were unable to identify the specific causes of meningitis other than the M. tuberculosis complex in the CSF samples, preventing us from determining the exact etiology of meningitis in all children and the specific causes of death among them. Further investigation into alternative causes of meningitis within the possible, probable, and confirmed TBM groups would provide deeper insights, improving diagnostic accuracy and aiding physicians in more effective patient management. Second, TBM patients were followed up for only one year since their diagnosis, and therefore, the long-term fate of these patients could not be determined. Future studies should explore the impact of early diagnosis and treatment—including cases classified as “trace calls”—on mortality outcomes in children. Finally, in the absence of a true gold standard, including the Ultra’s results in the CMRS or reference standard of uniform clinical case definition might introduce an incorporation bias. However, even when Ultra’s results were excluded from reference standards, Ultra demonstrated higher sensitivity than Xpert when compared to the reference standards clinically or microbiologically.

In conclusion, Ultra demonstrates superior sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) compared to Xpert, L-J culture, and AFB microscopy for detecting TBM in children using CSF samples. Notably, half of the Ultra positive CSF samples in children were categorized as ‘Trace Detected,’ with most of these cases receiving anti-TB treatment that might have been missed by other diagnostic methods. Given its high performance, Ultra can be implemented nationwide in high TB burden countries like Bangladesh for the rapid and accurate detection of TBM in children in clinical settings. This would enable physicians to initiate timely and appropriate treatment, potentially reducing mortality.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2024 1–68 (2024). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240101531.

Seddon, J. A., Tugume, L., Solomons, R., Prasad, K. & Bahr, N. C. The current global situation for tuberculous meningitis: Epidemiology, diagnostics, treatment and outcomes. Wellcome Open. Res. 4, 167. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15535.1 (2019).

Bahr, N. C. & Boulware, D. R. Methods of rapid diagnosis for the etiology of meningitis in adults. Biomark. Med. 8(9), 1085–1103. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm.14.67 (2014).

Chin, J. H. Tuberculous meningitis: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 4(3), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000023 (2014).

Sheu, J. J., Yuan, R. Y. & Yang, C. C. Predictors for outcome and treatment delay in patients with tuberculous meningitis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 338(2), 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181a590f1 (2009).

Hsu, P. C. et al. Prognostic factors of tuberculous meningitis in adults: A 6-year retrospective study at a tertiary hospital in Northern Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 43(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60018-7 (2010).

Marais, S. et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10(11), 803–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70138-9 (2010).

El-Hajj, H. H., Marras, S. A., Tyagi, S., Kramer, F. R. & Alland, D. Detection of Rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a single tube with molecular beacons. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39(11), 4131–4137. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.39.11.4131-4137.2001 (2001).

Piatek, A. S. et al. Molecular beacon sequence analysis for detecting drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Biotechnol. 16(4), 359–363. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0498-359 (1998).

Helb, D. et al. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Rifampin resistance by use of on-demand, near-patient technology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48 (1), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01463-09 (2010).

Blakemore, R. et al. Evaluation of the analytical performance of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48(7), 2495–2501. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00128-10 (2010).

World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Automated Real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF Assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in adults and children: Policy Update. (World Health Organization Copyright © World Health Organization, Geneva, 2013).

Chakravorty, S. et al. The new Xpert MTB/RIF ultra: improving detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and resistance to Rifampin in an assay suitable for point-of-care testing. mBio 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00812-17 (2017).

World Health Organization. WHO Meeting Report of a Technical Expert Consultation: Non-inferiority analysis of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra compared to Xpert MTB/RIF. (2024). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254792/1/WHO-HTM-TB-2017.04-eng.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 2017.

Bahr, N. C. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF ultra for tuberculous meningitis in HIV-infected adults: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30474-7 (2018).

Cresswell, F. V. et al. Xpert MTB/RIF ultra for the diagnosis of HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis: A prospective validation study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(3), 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30550-x (2020).

Donovan, J. et al. Xpert MTB/RIF ultra versus Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: A prospective, randomised, diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30649-8 (2020).

Pradhan, N. N. et al. Performance of Xpert(®) MTB/RIF and Xpert(®) ultra for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in children. Int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 26(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.21.0388 (2022).

Thwaites, G. et al. British infection society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. J. Infect. 59(3), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.011 (2009).

Cohen, J. F. et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 6(11), e012799. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799 (2016).

Banu, S. et al. Discordance across several methods for drug susceptibility testing of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in a single laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52(1), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02378-13 (2014).

World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 3: diagnosis - rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2021). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029415 1–142, Accessed Nov 2024.

Chin, J. H. et al. Optimal procedures for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Clin. Tuberc Other Mycobact. Dis. 14, 16–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jctube.2019.01.002 (2019).

Dorman, S. E. et al. Xpert MTB/RIF ultra for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: A prospective multicentre diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30691-6 (2018).

Denkinger, C. M. et al. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir J. 44(2), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00007814 (2014).

World Health Organization. WHO Meeting Report of a Technical Expert Consultation: non-inferiority Analysis of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra Compared To Xpert MTB/RIF (WHO, 2017). WHO/HTM/TB/2017.04.

Solomons, R. S., Visser, D. H., Marais, B. J., Schoeman, J. F. & van Furth, A. M. Diagnostic accuracy of a uniform research case definition for TBM in children: A prospective study. Int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 20(7), 903–908. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.15.0509 (2016).

Solomons, R. S. et al. Uniform research case definition criteria differentiate tuberculous and bacterial meningitis in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 59(11), 1574–1578. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu665 (2014).

HIV/AIDS Situation in Bangladesh-2023. Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS). https://asp.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/asp.portal.gov.bd/page/febb60ca_6e01_40df_89d7_e4b23954e191/2024-01-01-04-25-efadb44a8d21d4de4197c85593206752.pdf (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with the support of the Swedish International Development cooperation Agency (Sida) Sweden. icddr, b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of Sida to its research efforts. icddr, b is also grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh and Canada for providing core/unrestricted support. We extend our sincere gratitude to the health workers and staff at the participating healthcare facilities. We are especially grateful to the patients who took part in this study. Finally, we thank the laboratory staff for their exceptional efforts in carrying out this research.

Funding

This research work was supported by the Swedish International Development cooperation Agency (Sida) Sweden (Grant number: 54100089). The funders of this study had no role in the study’s design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.M.R. and S.B. conceptualized the study. S.K., F.K., A.M.R.R., S.A., M.B.A.M., M.S.R.S., and S.A. performed clinical investigation. S.M.M.R., R.N., A.S.M.I.I., M.K.M.U. performed laboratory investigation. S.M.M.R., R.N., F.K., A.M.R.R., R.K., and J.A.S. curated and analyzed data. S.M.M.R. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; and R.N., S.K., F.K., A.M.R.R., M.K.M.U., A.S.M.I.I., R.K., S.A., M.B.A.M., M.S.R.S., S.A., J.A.S. and S.B. critically reviewed and contributed to the manuscript. S.M.M.R. and S.B. supervised the study. S.M.M.R. and R.K. performed project administration. S.M.M.R. acquired funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of icddr, b (Protocol number: PR-19070). Written informed consents were obtained from parents or caregivers of all children and assents from children aged more than 11 years.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, S.M.M., Nasrin, R., Kabir, S. et al. Performance of Xpert MTB/RIF ultra for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in children using cerebrospinal fluid. Sci Rep 15, 13060 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97664-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97664-2