Abstract

Equisetum arvense L. (EAL) has a long history in traditional medicine for its ability to address various digestive and inflammatory conditions. Here, we aimed to evaluate the therapeutic potential of the EAL hydroalcoholic extract (HAEA) compared with the standard medications in a rat model of ulcerative colitis (UC) caused by acetic acid. Eighty-one male Sprague Dawley rats were acquired and randomly allocated into nine equal groups: healthy control group, negative control groups (receiving normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base), positive control groups (receiving asacol rectally and mesalazine orally), and test groups treated with different amounts of HAEA. At the end of the experiment (7 days), colonic injury was evaluated by macroscopic, biochemical, and stereological assessments. The effectiveness of HAEA on colonic tissue was proved by significantly decreasing the malondialdehyde (MDA) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) concentrations as well as myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and increasing the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in comparison to negative control groups. Particularly, the HAEA gel 10% rectal enema was significantly effective in decreasing MDA and IL-1β, as well as increasing GPx and SOD activities in comparison to positive control groups (P < 0.05). According to the stereological evaluations, HAEA 600 mg/kg orally and gel 10% rectal enema-treated groups, as well as the positive control groups, had significantly higher epithelium, submucosa, and muscularis mucosa volume density in comparison to the negative control groups (P < 0.001). This study showed promising therapeutic effects in all HAEA-treated groups, particularly HAEA gel 10% rectal enema in the induced UC rat model compared to conventional treatments. Both in vivo and in vitro findings indicate that EAL has the potential to be used as an additive therapeutic strategy in UC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a long-term condition that impacts the intestinal tissue and is classified into two types: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease. Due to an increase in IBD incidence worldwide, combined with an aging population, the prevalence of IBD has risen significantly over time. This chronic illness has an early onset and low mortality rate, which further contributesto its increasing prevalence1. The etiology of IBD, particularly UC, is linked to a combination of genetic and environmental factors that result in recurrent idiopathic inflammation and immune system dysregulation, which progresses slowly and affects the large intestine (colon) and rectum2. This disease manifests through various symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody diarrhea, bowel urgency, and anemia3. In addition, there are several complications that can arise as a result, such as megacolon, colorectal cancer, and extra-intestinal problems that affect the osteoarticular and skin systems4. Although the exact underlying process of UC is still unclear, recent studies indicate that an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1, TNF-α, and interleukin-6, has a crucial role in causing inflammation5.

At present, the primary treatments are focused on 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunomodulators (such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate), antitumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibodies, integrin blockers (such as vedolizumab and natalizumab), Janus kinase inhibitors, and surgical management6. However, these treatments have several side effects, including diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, nephrotoxicity, hypertension, weight gain, headache, nausea, and hepatic disorder7,8. Due to multiple relapses, corticosteroid dependency, and side effects from available treatments, there exists an urgent necessity for alternative therapies to address the constraints of existing therapeutic options. Current studies in the medical field have demonstrated the potential therapeutic benefits of traditional and herbal remedies, which possess a lower risk of side effects and promising therapeutic potential, making them a popular choice. In many developing countries, plant extracts are widely employed as a preferred method of treatment due to their availability, safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness9.

Equisetum arvense L. (EAL), also known as horsetail in English and “domeasb” in Persian, belongs to the Equisetaceae family and grows in North America, Europe, and Asia, including our country, Iran10,11,12. The EAL has excessively been used in traditional medicine in many parts of the world, as well as traditional Persian medicine, for treating various conditions due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-hemorrhagic, and wound-healing effects11,13,14,15,16. Numerous Equisetum species are commonly employed in traditional medicine among local people in countries like Turkey, Iran, Peru, and Spain to treat a range of diseases, including inflammatory conditions, rheumatoid arthritis, malignancies, gastrointestinal disorders, diarrhea, stomachache, peptic ulcers, hemorrhoids, and bleeding ulcers16,17,18,19,20. Furthermore, EAL was not only used as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agent in traditional medicine, but also, pharmacological studies demonstrated that it reduces the synthesis of TNF-α and IFN-γ, therefore providing anti-inflammatory activities16,21,22. The EAL was rich in several compounds, such as salicylic, phenolic, linolenic, flavonoids, luteolin, saponin, glycosides, tannins, triterpenoids, and ascorbic acid19,23,24. Another study evaluated 13 herbs in Ukrainian traditional medicine for anti-inflammatory effects using molecular docking and proved that EAL contains efficient compounds like quercetin and tannin that can inhibit proinflammatory enzymes, including lipoxygenase-5 and cyclooxygenase-2, suggesting its potential in treating UC25.

Taking into account the anti-inflammatory properties of EAL and the necessity to explore new alternatives therapeutic methods against UC, which is becoming increasingly common worldwide, the present study was designed to investigate the therapeutic effects of a hydroalcoholic extract of EAL (HAEA) in experimentally induced UC in rats and compare them with those of standard treatments.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The Animal Care Committee at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences has granted approval for the study protocol (ethical code: IR. SUMS 11772-6, Date: 9-01-95). The research was conducted in accordance with all institutional and international guidelines concerning the care and use of animals. Additionally, the guidelines for Animal Research Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) were properly followed.

Preparation of hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L.

The EAL was obtained and collected during the summer in Sari, Mazandaran province, Iran, and it was identified by the Pharmacognosy Department at the School of Pharmacy, Shiraz, University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The voucher specimen (MPH-2248) for the identified plant has been archived at the Herbarium of Medicinal Plants and Drugs Research Institute (MPH) located at Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran, Iran. The plant was air-dried in the shade, away from sunlight, at room temperature (25 °C) for one month. After drying, the plant was ground and used to prepare a hydroalcoholic extract. In order to prepare the HAEA, 100 g of dried EAL were ground into a powder and subsequently percolated with 70% ethanol three times at ambient temperature over a duration of 72 h. Afterward, the extract underwent filtration and was evaporated at reduced pressure, yielding 20 g of dried extract (PH:7). The phytochemical study of EAL was reported in previous studies in our country using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)15,26.

Determination of total phenolic content of hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L.

The total phenolic content (TPC) of the extract was evaluated using spectrophotometry, following the method described by Waterhouse27with some modifications. The diluted sample, measuring 40 µl, was combined with 200 µl of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 3.5 ml of distilled water. After shaking for 8 min, 600 µl of a 0.25% sodium carbonate solution was added to the mixture. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and subsequently incubated in the dark for a duration of 30 min, followed by a measurement of the absorbance at 765 nm. In order to establish a standard curve, we carried out the same experiment for the standard solution of gallic acid28,29. Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg of GA/g of dE).

Determination of antioxidant capacity of hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L.

The antioxidant capacity of HAEA was determined using the stable free radical 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH°), following William’s method30. First, a solution of 10−4DPPH in methanol and various concentrations (31, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1000 µg/ml) of the extract in methanol were prepared, and 3800 µl of DPPH solution was mixed with 200 µl of the samples. The solutions in the test tubes were shaken well and incubated at room temperature in the dark for a duration of thirty minutes. The spectrophotometer wavelength was set at 517 nm, and the percentage of the diminished DPPH was calculated31,32. Inhibition-concentration curves were generated using the Curve Expert statistical program, and the concentration of extract that inhibited DPPH formation by 50% (IC50) was established.

Gel preparation

The gel was prepared based on a previous study33. In summary, a 5% glycerol solution was combined with a 2% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (NaCMC) and mixed using a mixer at 500 RPM. Afterward, EAL extract (10% and 5%) was mixed with deionized water, and the solution was carefully combined with the glycerol–NaCMC solution. At last, the gel was blended for a period of 30 min to get a homogeneous mixture and subsequently gathered in an aluminum tube and stored in a refrigerator.

Experimental design

A total of eighty-one male Sprague Dawley rats, weighing between 180 and 220 g, were purchased from the Laboratory Animals Breeding Center at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, located in Shiraz, Iran, and subsequently allocated to the following nine groups of nine rats each, as outlined in Table 1. Group 1 consisted of healthy rats that received no intervention (healthy control group). Group 2 rats were one of the negative control groups that received 1 cc of normal saline daily (normal saline group), and group 3 rats were the other negative control group that received 1 cc of carboxymethyl cellulose gel base daily (gel base group) after induction of UC using acetic acid. Group 4 of rats was one of the positive control groups and received 1 cc of asacol rectally daily (5-ASA enema). Group 5 of rats was the other positive control group and received oral mesalazine at a dosage of 10 mg/kg daily (5-ASA oral) after induction of UC with acetic acid. Groups 6 and 7 were rats with acetic acid-induced UC receiving HAEA orally with dosages of 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg, respectively. Groups 8 and 9 were rats with acetic acid-induced UC receiving HAEA rectal enema with gel 5% and 10%, respectively.

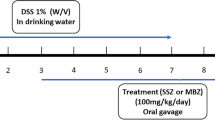

Induction of UC and treatment protocol

Rats were maintained under NPO conditions for a duration of 24 h, following which they were anesthetized using xylazine at a dosage of 5 mg/kg and ketamine at a dosage of 90 mg/kg. A polyethylene catheter was inserted into the rectum and advanced for 8 cm, then UC was induced in rats by injecting 2 ml of acetic acid 3% through the catheter34,35. During the study, in order to establish ulcerative colitis in rats, we employed clinical observations, including diarrhea and the presence of bloody stools, to establish ulcerative colitis in rats. Additionally, a series of pathological tests were randomly conducted on several rats. Moreover, before the study, a pilot study was repeatedly conducted to confirm the ulcerative colitis model.

All treatments began 12 h following colitis induction and were administered daily for seven days35. Through decapitation, the rats were euthanized once the experiment was completed on the eighth day. Afterward, we carefully harvested the final 10 cm of the colon for a thorough examination. The colon lumen was carefully cut open longitudinally using clean excisions and washed with normal saline. The final 10 cm of the colon was divided into two parts: the first 5 cm was immersed in buffered formalin and stored for further pathological and stereological assessments, while the second 5 cm was immediately frozen in an azote tank at −150 degrees Celsius for future biochemical evaluation.

Macroscopic and microscopic evaluation

For macroscopic evaluation, after measuring colon length, specimens were longitudinally incised and rinsed with normal saline. The extent of the damage to the colon was assessed macroscopically according to the Morris scoring system36.

For microscopic evaluation, the colon specimens were carefully fixed in buffered formalin and subsequently embedded in paraffin to maintain their structural integrity. Afterward, the colon sections were stained using Masson’s trichrome and subsequently examined under a microscope at ×10 magnification.

Determination of malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the rat colonic tissues

MDA levels were measured in rat colonic tissues as an index of lipid peroxidation using a thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay based on the manufacturer’s protocol. In summary, 100 µl of colonic tissue homogenate was combined with 2.5 ml kit reaction buffer and subsequently heated to 80 degrees °C for a duration of one hour. The sample was then left to cool down and centrifuged at room temperature. Subsequently, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 532 nm using an Agilent spectrophotometer37.

Determination of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the rat colon

The MPO activity was evaluated in colonic tissues as previously outlined38. In summary, 2 ml of hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB) buffer, which contained 0.5% HTAB in 50 mm phosphate buffer at pH 6.0, was combined with 100 mg of colonic tissue. The mixture was homogenized on ice for six sessions of 45 s each. The samples were subsequently centrifugated at a speed of 3000 RPM for a duration of 30 min at a temperature of 4 degrees °C, after which the supernatant was carefully separated. Afterward, 10 µl of supernatant was mixed with 200 µl of phosphate buffer, which contained 0.167 mg/ml 0-dianisidine hydrochloride and 1.25% hydrogen peroxide. Then, we calculated the samples’ absorbance at 450 nm, and each unit of MPO activity is characterized by the degradation of 1 μm of peroxide per minute at a temperature of 25 degrees °C. Using the standard curve, the activity of MPO was measured35,38.

Determination of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels in colonic tissues

The activities of GPx and SOD as antioxidative enzymes were assessed using commercial kits (Biorexfars, Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and previous reports31.

Determination of levels of interleukin-1β(IL-1β) in colonic tissues

The levels of IL-1β in the rat colonic tissues were determined using ELISA kits. The results were presented as pg/mg protein.

Estimation of the volume density ratio of the colon structure

Using the immersion method, the volume of the colon was determined. The colon was suspended with a thread in a container that was filled with normal saline. The measurement was performed by calculating the difference in the weight of the container before and after the suspension. Next, we divided this difference by 1.0048, which represents the specific gravity of the saline solution. Colon samples were obtained, and histological Sect. (4 μm) were coloured with hematoxylin and eosin. In order to assess the volume density ratio (Vv) of the histological structures, such as mucosal epithelium, submucosa, muscularis mucosae, and muscularis externa we employed the method of point-counting and Delesse’s formula:

VV (structure) = \(\:\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}p\) (structure)/\(\:\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}p\) (reference)

In this formula, “ΣP structure” represents the total number of points that intersect with the favored structure within the colon, while “ΣP references” indicates the total number of points that hit the colon section for each animal in the study35. This calculation helps in determining the volume density ratio of the colon structures being examined, as shown in Fig. 1.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed to assess the normality of distribution utilizing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± SD, and they were analyzed using a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test for pairwise comparisons. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. The analysis was conducted using SPSS software, version 16 (SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L.

The total polyphenol content of HAEA was 171.5 ± 4.95 mg of GA/g of dE. Also, HAEA depicted an IC50 = 72.33 ± 7.77 µg/ml for DPPH scavenging activity (IC50 = 3.01 ± 1.72 μm for quercetin as a positive control).

Macroscopic and microscopic evaluation

As shown in Fig. 2, the normal saline and gel base-treated groups demonstrated macroscopic inflammation, edema, and ulceration in colonic mucosa. The colonic tissue of the HAEA rectal enema gel 10% treated group showed significantly attenuated macroscopic inflammation, edema, hemorrhage, and ulceration compared to that of normal saline and gel base-treated groups. Figure 3 illustrates the results of the Morris macroscopic scoring system, indicating no significant differences between the groups treated with the 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine) compared to HAEA enema gel 10% and HAEA oral treated group at a dosage of 600 mg/kg. Nonetheless, a significant difference in macroscopic scoring was observed among the groups administered normal saline and gel base treatment compared to all other HAEA-treated groups (Fig. 3). Figure 4 demonstrates the microscopic evaluation of colon sections staining with Masson’s trichrome, which revealed a loss of epithelial cells, thickening of muscularis tissue, disruption of crypt architecture, crypt abscess formation, decreased goblet cells, and leukocyte infiltration in groups receiving normal saline and gel base; while the HAEA-treated groups showed signs of recovery.

Representative macroscopic image of the colonic mucosa in the different groups of rats. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). ✷: hemorrhage; ●: ulcerations; ◼: edema.

Comparison of the macroscopic scorings based on the Morris scoring system36 in different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, and c: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Microscopic slides of colon samples from rats. The healthy control group (A), while the induced colitis groups included: normal saline recipients (negative control) (B), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) recipients (positive control) (C), hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally at 300 mg/kg (D), HAEA orally at 600 mg/kg (E), gel base recipients (negative control) (F), 5-ASA enema (asacol) recipients (positive control) (G), HAEA enema gel 5% (H), and HAEA enema gel 10% (I). The samples were stained with Masson’s trichrome and observed under a magnification of ×10. In the colitis group, notable findings included the loss of epithelial cells (arrow), thickening of the muscularis tissue, destruction of crypt architecture, crypt abscess formation, reduced goblet cells, and leukocyte infiltration (arrowhead). Conversely, the treatment groups exhibited a trend towards recovery.

The effects of hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L. on colonic tissue MDA levels

The levels of MDA in all the HAEA-treated groups, 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups were significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared to the groups receiving normal saline and gel base treatment. Moreover, we did not observe any significant difference between the MDA levels in HAEA gel 5%, oral HAEA (300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) treated groups, and 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups. However, a significant difference was seen in the MDA level in the HAEA enema gel 10% group in comparison to all other HAEA-treated and 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups. Furthermore, no significant difference in MDA levels was observed between the healthy control group and those treated with HAEA enema gel 10%. (Fig. 5).

Comparison of the malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, and c: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The effects of hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L. on colonic tissue MPO levels

According to Fig. 6, we observed a significant difference in the levels of MPO in all HAEA-treated groups, including oral HAEA (HAEA 600 mg/kg and 300 mg/kg) and HAEA rectal enema (gel 5% and 10%), and 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups, compared to the groups receiving normal saline and gel base treatment (p < 0.05). Moreover, the MPO level in the group that received HAEA enema gel 10% was significantly diminished in comparison to all other HAEA-treated groups (p < 0.05), and no significant difference was observed between the healthy control group and the HAEA enema gel 10%. Additionally, there was no significant difference between the MPO levels in all HAEA-treated groups and 5-ASA enema and oral-treated groups.

Comparison of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, c, d, and e: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The effects of hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L. on colonic tissue GPx level

The GPx demonstrated a significant higher activity in the group treated with 600 mg/kg of oral HAEA, HAEA rectal enema (gel 5% and 10%), and 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups (p < 0.05) compared to normal saline and gel-base treated groups. Additionally, a significantly higher activity of GPx in the group receiving 10% HAEA enema gel was observed in comparison to 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups, as well as all other HAEA-treated groups. Moreover, there was no significant difference between the GPx activity in the HAEA enema gel 10% treated group and the healthy control group (Fig. 7).

Comparison of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) levels in different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, c, d, e, and f: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The effects of hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L. on colonic tissue SOD level

The levels of SOD in the rats exposed to all HAEA-treated groups, 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups were significantly (p < 0.05) higher than that in the normal saline and gel-base-treated groups. Moreover, HAEA rectal enema gel 10% and oral HAEA with a 600 mg/kg dosage were significantly more effective than 5-ASA oral (mesalazine). Also, there was no significant difference between SOD levels in these two groups and healthy control group (Fig. 8).

Comparison of superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels in different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, c, and d: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The effects of hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L. on colonic tissue IL-1β levels

The levels of IL-1β in normal saline and gel-based groups were significantly higher compared to all HAEA-treated groups, and 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups (p < 0.05). However, of all the HAEA-treated groups, only HAEA rectal enema gel 10% and oral HAEA with the dosage of 600 mg had the potency to reduce IL-1β levels significantly in comparison to 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups (p < 0.05). Additionally, no significant difference was seen between the levels of IL-1β in these two HAEA-treated groups and the healthy control group (Fig. 9).

Comparison of IL-1β levels in colon tissue in different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, c, and d: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Stereological findings in colonic tissues

Stereological findings in colonic tissues are presented in Fig. 10, wherein we evaluated the volumes of the epithelium, submucosa, muscularis mucosae, and muscularis externa. Regarding the volume density assessment of the epithelium, submucosa, and muscularis mucosa, the healthy control group exhibited significantly higher levels compared to the normal saline (all P < 0.001), base gel group (all P < 0.001), oral HAEA at the dosage of 300 mg/kg, and HAEA gel 5% enema treated groups (P < 0.001 and P = 0.009 for epithelium, and P < 0.001 for submucosa and muscularis mucosa, respectively). No significant difference was observed between the healthy control compared to 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups, and oral HAEA at the dosage of 600 mg/kg and HAEA gel 10% enema treated groups (P = 0.320, 0.291, 0.511, 0.501 for epithelium, and 0.172, 0.425, 0.333, 0.339 for submucosa, and 0.633, 0.794, 0.907, and 0.633 for muscularis mucosa, respectively). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the epithelium, submucosa, and muscularis mucosa volume density between 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups and oral HAEA at the dosage of 600 mg/kg and HAEA gel 10% enema-treated groups. However, 5-ASA enema (asacol) and oral (mesalazine)-treated groups and oral HAEA at the dosage of 600 mg/kg and HAEA gel 10% enema treated groups demonstrated significantly higher epithelium, submucosa, and muscularis mucosa volume density compared to normal saline and gel-base treated groups. This was also the case regarding epithelium volume density between the oral HAEA at the dosage of 300 mg/kg and HAEA gel 5% enema-treated groups compared to normal saline and gel-base treated groups.

Concerning muscularis externa volume density, normal saline and gel-based groups had significantly higher values compared to all other groups (P < 0.001 for all). However, there was no significant difference between the healthy group in comparison to 5-ASA enema (asacol), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine), and all HAEA-treated groups.

Comparison of stereological changes in colon tissue of different experimental rat groups with induced ulcerative colitis. Box plots illustrating stereological variables, including volume density of the epithelium (A), submucosa (B), muscularis externa (C), and muscularis mucosae (D) in rats with ulcerative colitis. Experimental groups included normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base (negative control), 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) (positive control), healthy control group, and the groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Equisetum arvense L. (HAEA) orally (HAEA 300 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg) and enema (HAEA gel 5% and 10%). a, b, and c: The post-hoc Tukey test, utilized for comparing groups, indicates that groups sharing the similar superscripts do not differ significantly (p ≥ 0.05). Conversely, different superscripts letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study investigated the healing effects of HAEA extracts in acetic acid-induced UC rat models, and our findings demonstrated that this herbal extract has great positive effects in treating UC due to a significant decrease in inflammatory biomarkers and oxidative indices compared to normal saline and gel-based groups (p< 0.05). Moreover, this claim was in accordance with stereological and macroscopic examinations. In detail, a comparison of oxidative indices and inflammatory markers, including MDA, IL-1β concentrations, MPO, GPx, and SOD activities among orally and rectally HAEA-treated groups, normal saline and carboxymethyl cellulose gel base treated groups, 5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol) treated groups, and healthy control group, were performed. The findings of the current study demonstrated that all herbal treated groups decreased chronic inflammation and HAEA rectal enema gel 10% had the best effectiveness (approximately 45%, 62%, and 30% reduction in MDA, MPO, IL-1β and 42% and 46% improvement in GPx and SOD activities compared to the normal saline-receiving group, respectively) and this enema gel showed even better efficiency than the conventional treatments (5-ASA oral (mesalazine) and 5-ASA enema (asacol)). In comparison to conventional chemical treatments, herbal products have demonstrated fewer side effects and lower costs while maintaining comparable efficacy9. Based on our findings, HAEA holds remarkable potential as an innovative medication in the management of UC.

For centuries, the use of medicinal plants and their extracts as potential candidates for therapeutic purposes has been widely recognized. Owing to their beneficial properties, they have been employed in the treatment of many diseases23. The EAL is used in traditional medicine to treat various diseases and has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial effects. The EAL has several well-known compounds, including alkaloids, phytosterols, tannins, triterpenoids, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids. Significantly, this plant is rich in antioxidant agents, particularly styryl pyrones and flavonoid quercetin 3-O-glucoside, which play a vital role in its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects by demonstrating reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging inhibitory activities22,23,39. Moreover, this plant has high levels of elements such as K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Si4+, and Se2−, some of which play a critical role in the action of SOD (Cu/Zn-SOD) and GPx (Se-protein) enzymes which work as intracellular antioxidant enzymes23,40,41. Hence, this plant possesses numerous beneficial properties in reducing inflammation.

The appropriate therapeutic strategies for UC are chosen based on the severity (mild, moderate, or severe) and extent of the disease42,43. The extent of the UC can vary over time; however, distal involvement of the colon and rectum is more common, affecting around two-thirds of UC patients. The presence of more distal disease provides an opportunity to employ rectally administered local therapies, which can effectively target the site of inflammation and minimize systemic drug exposure42. The treatment of UC is divided into medical therapy and surgery. The surgical approach is the only curative treatment, but due to the high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with it, it is used in refractory cases or patients with neoplasia. In all cases, the first-line therapy includes the usage of topical mesalazine ± topical steroids (in different forms of foam, suppositories, or enemas) alone or in combination with oral therapies6,43. In trials with over 50% of patients with left-sided or extensive disease, the combination of oral and topical mesalazine was the most or second most effective treatment compared to other forms of mesalazine. In clinical trials involving over 50% of patients with proctitis or proctosigmoiditis, topical mesalazine consistently emerged as the most effective treatment in most analyses, highlighting the potential of topical mesalazine as a preferred treatment option in these cases44. The results of the present study indicated that the topical use of HAEA extract in the form of a 10% gel rectal enema was more effective in reducing inflammation than all other HAEA-treated groups. It is important to note that in our study, the rectal enema form of asacol was more effective (not significantly) than the oral administration of mesalazine in reducing inflammation based on all inflammatory indicators, except for MDA. The superior effectiveness of the rectal administration route, as indicated by our findings, may be attributed to its direct contact with the site of inflammation within the colon rectum. Although the etiology of UC has not been completely discovered, certain pathophysiological factors such as immune dysfunction, genetic susceptibility, alteration of gut microflora, some environmental factors, and diet are reported to cause UC2,45. Several studies demonstrated that the etiology of UC is associated with the generation of free radicals, including ROS, which result in oxidative stress (OS), oxidative damage, lipid peroxidation (LPO), upregulating inflammatory cytokines, and DNA damage, causing excessive apoptosis. An increase in the levels of MDA, which is a significant indicator of LPO in the colon tissue, is induced by ROS. Moreover, overproduction of ROS such as superoxide anions (O2−), hydrogen peroxides (H2O2), hypochlorous acid (HOCl), and a decrease in antioxidant enzymes including SOD, GPX, catalase (CAT) in the intestinal mucosa will contribute to severe inflammation in patients with UC. Superoxide anions can be transformed to more stable H2O2 by SOD catalysis, and then H2O2 can be reduced to H2O by CAT and GPx systems or be catalyzed by MPO into HOCl, which is 100 times more toxic than H2O246,47,48. IL-1β has been identified as a crucial inflammatory factor in UC, and over-expression of IL-1β has been associated with higher intestinal permeability and activation of dendritic cells and macrophages, which then contributes to inflammation. Furthermore, IL-1β often works in conjunction with pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and interleukin-6 to mediate inflammatory responses in the lamina propria45. Consequently, the administration of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents may prove beneficial in the management of UC.

The MDA is one of the excellent predictors of LPO, and in this study, we proved a significant decrease in the MDA level in all our HAEA-treated groups compared to normal saline and gel-based groups (P < 0.05). Particularly, the rectal enema with gel 10% HAEA was extremely effective in reducing MDA. In 2022, Ibrahem et al. conducted a study to evaluate the effect of dried EAL supplements on rats with induced osteoporosis. He proved a significant decrease in MDA levels after treatment with EAL supplements compared to the control group who did not get EAL supplements (P< 0.05)49. Yoo et al. carried out a study to assess ethanol extract of EAL effect on aging rats induced by D-galactose and demonstrated a significant decrease in MDA levels in the EAL-treated group in comparison to the negative control group by suppressing OS in rats50. These studies, in line with our findings, prove the antioxidative effect of EAL by reducing MDA.

The MPO is an enzyme mostly expressed and stored in neutrophils and catalyzes the reaction between hydrogen peroxide and physiological halides (such as Cl−) to form reactive oxidants of ROS that are involved in the pathogenesis of UC46. Using HPLC analysis, the EAL was proven to be very rich in flavonoids, especially luteolin, and β-sitosterol51,52, which both have significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. In 2020, Boeing et al. demonstrated that luteolin diminishes irinotecan-induced intestinal mucositis in mice model by decreasing MPO levels53, and in 2023, Makran et al. proved that β‐sitosterol as a dietary supplement reduces MPO levels in rats with dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis54. The findings of this study indicated a significant drop in MPO levels in all the groups that were treated with HAEA in comparison to normal saline and gel-based groups, with HAEA 10% rectal enema gel being significantly more effective than all other HAEA groups (P < 0.05).

The SODs are intracellular antioxidant enzymes that convert superoxide radicals to O2 and H2O2catalytically to limit their harmful effects46. The levels of SOD in IBD patients are currently being used as UC biomarkers, and the decrease in SOD activity may account for the generation of reactive species and the intensity of LPO55. Ibrahem et al., in 2022, proved a significant increase in SOD levels after treatment with EAL supplements in osteoporosis-induced rat models (P< 0.05)49. The EAL is an excellent source of vitamins C and E and contains significant amounts of copper and zinc. These essential elements are crucial for the activation of SOD, which in turn is responsible for neutralizing active oxygen species10. In agreement with previous studies, we also proved that SOD levels increased significantly in all our HAEA-treated groups compared to normal saline and gel-based groups (P < 0.05).

The enzyme GPx plays a crucial role as an antioxidant by catalyzing the reduction of hydrogen peroxide to water. It has been observed that IBD activity corresponds with decreased GPx activity56. With the use of HPLC analysis, previous studies have demonstrated that EAL exhibits a high concentration of flavonoids, including kaempferol57. Kaempferol is well recognized for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and its capacity to inhibit ROS activity. In 2020, Al-Brakati et al. investigated the effect of kaempferol on cadmium-induced cortical injury in rats and proved that after treatment with kaempferol, not only GPx activity was promoted significantly (P< 0.05), but also upregulation in the gene expression of GPx was observed58. Kucuk et al. carried out a study to investigate the effect of herbal products, including EAL, in a rat model with cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and demonstrated that the GPx level was considerably higher in the group that received the herbal products (P < 0.05). In line with these studies, we also proved significantly higher activity of GPx in HAEA-treated groups.

One of the key cytokines in IBD is IL-1β, and it has been observed that individuals with UC have higher levels of IL-1β than healthy individuals. Furthermore, studies have shown that by inhibiting IL-1β, there has been an improvement in colitis lesions48. In 2022, Shiba et al. evaluated the effect of EAL on alveolar bone destruction in the lipopolysaccharide-induced periodontitis rat model and demonstrated that EAL significantly inhibited TNF-α mRNA and IL-1β mRNA expression (P< 0.05)59. In the present study, it was also proved that all HAEA-treated groups had significantly lower levels of IL-1β compared to normal saline and gel-based groups (P < 0.05).

Based on our knowledge, no similar studies, neither in animal models nor in humans, exist to study the beneficial effects of horsetail hydroalcoholic extract for the treatment of UC. Based on the decrease of the MDA level as an indicator of LPO, reducing the IL-1β as an indicator of inflammatory function, an increase of the GPx, and SOD activities as enzymes involved in the antioxidant system, and the reduction of MPO as an oxidative enzyme, it can be concluded that both topical and systemic forms of EAL extracts possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, effective in treating UC.

Conclusion

At present, UC is typically treated with 5-ASA, steroids, and immunosuppressive medications. However, our research indicates that HAEA could serve as a promising new therapeutic agent for UC. This conclusion is based on its ability to inhibit inflammatory and oxidative pathways while increasing antioxidant enzyme levels. Additionally, stereological assessments have proved the healing effects of EAL on induced UC in rats. In summary, EAL could be considered an additive therapeutic agent in UC patients, and this study’s findings could provide valuable evidence for further clinical trials and prospective studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine-Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- ARRIVE:

-

Animal Research Reporting In vivo Experiments guidelines

- CAT:

-

catalase

- DPPH°:

-

1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl

- EAL:

-

Equisetum arvense L

- GPx:

-

glutathione peroxidase

- HAEA:

-

Hydroalcoholic extracts of Equisetum arvense L

- HTAB:

-

Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1β

- LPO:

-

Lipid peroxidation

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- MPO:

-

Myeloperoxidase

- OS:

-

Oxidative stress

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TPC:

-

Total phenolic compound

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

- HPLC:

-

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

References

Mak, W. Y., Zhao, M., Ng, S. C. & Burisch, J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East Meets West. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 380–389 (2020).

Kofla-Dłubacz, A. et al. Etiology of IBD—Is it still a mystery?? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 12445 (2022).

Loftus, E. V. et al. Upadacitinib therapy reduces ulcerative colitis symptoms as early as day 1 of induction treatment. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 2347–2358e6 (2023).

Lichtenstein, G. R. et al. Increased lifetime risk of intestinal complications and extraintestinal manifestations in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 32–43 (2022).

Kałużna, A., Olczyk, P. & Komosińska-Vassev, K. The role of innate and adaptive immune cells in the pathogenesis and development of the inflammatory response in ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 400 (2022).

Raine, T. et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J. Crohns Colitis. 16, 2–17 (2022).

Roselli, M. & Finamore, A. Use of synbiotics for ulcerative colitis treatment. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 15, 174–182 (2020).

Segal, J. P., LeBlanc, J. F. & Hart, A. L. Ulcerative colitis: an update. Clin. Med. 21, 135–139 (2021).

Gupta, M. et al. Natural compounds as safe therapeutic options for ulcerative colitis. Inflammopharmacology 30, 397–434 (2022).

Al-Snafi, P. D. A. E. The Pharmacology of equisetum arvense- A review. IOSR J. Pharm. 07, 31–42 (2017).

Dolatkhahi, M., Dolatkhahi, A. & Bagher Nejad, J. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Arjan - Parishan protected area in Fars Province of Iran. Avicenna J. Phytomedicine. 4, 402–412 (2014).

Makia, R., sammarrae, K. W. A., Halbosiy, M. M. A. & Mashhadani, M. H. A. Pharmacology of the species equisetum (Equisetum arvense). GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 18, 290–294 (2022).

Asgharikhatooni, A., Bani, S., Hasanpoor, S., Mohammad Alizade, S. & Javadzadeh, Y. The effect of equisetum arvense (horse tail) ointment on wound healing and pain intensity after episiotomy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 17, e25637 (2015).

Irfan, M. et al. Ethnomedicinal and traditional uses of the ferns of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Braz J. Biol. 84, e250256 (2024).

Malekpour-Irdemousa, M. et al. Agro-morphological and phytochemical diversity and silica content variability among Iranian populations of common horsetail (Equisetum arvense L). J. Med. Plants. 20, 83–101 (2021).

Sureshkumar, J. et al. Genus equisetum L: taxonomy, toxicology, phytochemistry and Pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 314, 116630 (2023).

Boeing, T., Tafarelo Moreno, K. G., Junior, G., Mota Da Silva, A. & De Souza, P. L. Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of the Genus Equisetum (Equisetaceae): A Narrative Review of the Species with Therapeutic Potential for Kidney Diseases. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 1–17 (2021). (2021).

Gurbuz, I., Yesilada, E. & Ito, S. An anti-ulcerogenic flavonol diglucoside from equisetum palustre L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 121, 360–365 (2009).

Luanda, A., Ripanda, A. & Makangara, J. J. Therapeutic potential of equisetum arvense L. for management of medical conditions. Phytomedicine Plus. 3, 100444 (2023).

Yeganegi, M. et al. Equisetum Telmateia extracts: chemical compositions, antioxidant activity and antimicrobial effect on the growth of some pathogenic strain causing poisoning and infection. Microb. Pathog. 116, 62–67 (2018).

Jeong, S. Y. et al. Phytochemical investigation of equisetum arvense and evaluation of their Anti-Inflammatory potential in TNFα/INFγ-Stimulated keratinocytes. Pharmaceuticals 16, 1478 (2023).

Shiba, F. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of glycyrrhizin with equisetum arvense extract. Odontology 109, 464–473 (2021).

Dormousoglou, M. et al. Investigation of the genotoxic, antigenotoxic and antioxidant profile of different extracts from equisetum arvense L. Antioxidants 11, 1393 (2022).

Ivanišová, E. et al. Polyphenol content, mineral compounds composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of selected medicinal herbs from Slovak Republic. Appl. Sci. 13, 1918 (2023).

Vyshnevska, L., Severina, H. I., Prokopenko, Y. & Shmalko, A. Molecular Docking investigation of anti-inflammatory herbal compounds as potential LOX-5 and COX-2 inhibitors. Pharmacia 69, 733–744 (2022).

Eghlima, G., Esmaeili, H., Frzaneh, M. & Mirjalili, M. H. Multivariate analysis of equisetum arvense L. Ecotypes based on silicon content, phytochemical and morphological characterization. Silicon 16, 115–122 (2024).

Waterhouse, A. L. Determination of total phenolics. 6, I1. 1.1-I1. (2002). 1.8.

Akbari, A., Nasiri, K., Heydari, M., Mosavat, S. H. & Iraji, A. The protective effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Ginger) on Ethanol-Induced reproductive toxicity in male rats. J. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 22, 609–617 (2017).

Ardakani Movaghati, M. R. et al. Efficacy of black seed (Nigella sativa L.) on kidney stone dissolution: A randomized, double-blind, placebo‐controlled, clinical trial. Phytother Res. 33, 1404–1412 (2019).

Brand-Williams, W., Cuvelier, M. E. & Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 28, 25–30 (1995).

Koohi-Hosseinabadi, O. et al. Biochemical, hematological, and pathological related healing effects of elaeagnus angustifolia hydroalcoholic extract in 5-fluorouracil-induced oral mucositis in male golden hamster. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 24, 24447–24453 (2017).

Ostovar, M. et al. Effects of citrullus colocynthis L. in a rat model of diabetic neuropathy. J. Integr. Med. 18, 59–67 (2020).

Tanideh, N. et al. Healing effect of pistacia Atlantica fruit oil extract in acetic Acid-induced colitis in rats. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 39, 522–528 (2014).

Rezaei, N., Eftekhari, M. H., Tanideh, N., Mokhtari, M. & Bagheri, Z. Comparison of antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory effects of honey and spirulina platensis with sulfasalazine and mesalazine on acetic Acid-Induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Galen Med. J. 8, (2019).

Tanideh, N. et al. Protection by pure and genistein fortified extra Virgin Olive oil, Canola oil, and rice Bran oil against acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Food Funct. 11, 860–870 (2020).

Morris, G. P. et al. Hapten-induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology 96, 795–803 (1989).

Mardani, M. et al. Hydroalcoholic extract of Carum carvi L. in oral mucositis: a clinical trial in male golden hamsters. Oral Dis. 22, 39–45 (2016).

Alizade Naini, M. et al. The Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Quercus brantii Extract on TNBS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Rats. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 1–12 (2021). (2021).

Roumil, I. et al. Acute toxicity and assessment of antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory capacity of different extracts of equisetum arvense. South. Asian J. Exp. Biol. 12, 318–326 (2022).

Malyar, R. M. et al. Selenium/Zinc-Enriched probiotics improve serum enzyme activity, antioxidant ability, inflammatory factors and related gene expression of Wistar rats inflated under heat stress. Life Sci. 248, 117464 (2020).

Safonov, V., Ermakov, V., Danilova, V. & Yakimenko, V. Relationship between blood superoxide dismutase activity and zinc, copper, glutathione and metallothioneines concentrations in calves. Biomath 10, (2021).

Cohen, R. D. & Weisshof, R. A. Comprehensive review of topical therapies for distal ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 21–27 (2020).

Ferretti, F., Cannatelli, R., Monico, M. C., Maconi, G. & Ardizzone, S. An update on current pharmacotherapeutic options for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 2302 (2022).

Barberio, B. et al. Efficacy of oral, topical, or combined oral and topical 5-Aminosalicylates, in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and network Meta-analysis. J. Crohns Colitis. 15, 1184–1196 (2021).

Du, L. & Ha, C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. North. Am. 49, 643–654 (2020).

Wan, Y., Yang, L., Jiang, S., Qian, D. & Duan, J. Excessive apoptosis in ulcerative colitis: crosstalk between apoptosis, ROS, ER stress, and intestinal homeostasis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 28, 639–648 (2022).

Oladele, J. O. et al. Telfairia occidentalis mitigates dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis in rats via suppression of oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and inflammation. J. Food Biochem. 45, (2021).

Yin, Q. et al. An immuno-blocking agent targeting IL-1β and IL-17A reduces the lesion of DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Inflammation 44, 1724–1736 (2021).

Ibrahem, E., Mohamed, G. & El Gazar, A. Therapeutic effect of equisetum arvense on bone and scale biomarkers in female rats with induced osteoporosis. Egypt. J. Chem. 65, 457–466 (2022).

Yoo, H., Kim, H. S., Kim, H., Ahn, S. & Zhou, X. Ethanol extracts of oenothera laciniata sprout, equisetum arvense L., and Ailanthus altissima leaves improve antioxidant activities in D-galactose induced aging rat model. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 4, nzaa040094 (2020).

Ismail, A., Al-Khasreji, T. & Maulood, B. Flavonoids content in methanolic extract of equisetum arvense L.(Horsetail) from Kurdistan region - Iraq. J. Biotechnol. Res. Cent. 14, 47–51 (2020).

Svogie, A., Mothibe, M. & Bassey, K. Evaluation of South African equisetum arvense as an antidiabetic, antioxidant and immune booster using economical thin layer chromatography Bio-autography. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 3, 181–188 (2022).

Boeing, T. et al. Luteolin prevents irinotecan-induced intestinal mucositis in mice through antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory properties. Br. J. Pharmacol. 177, 2393–2408 (2020).

Makran, M., Giner, R. M., Cilla, A. & Recio, M. C. Garcia-Llatas, G. A dietary supplement containing plant sterols exerts a positive effect on inflammatory markers in a chronic colitis murine model. Biol. Life Sci. Forum. 26, 57 (2023).

Guan, G. & Lan, S. Implications of Antioxidant Systems in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 1–7 (2018). (2018).

Pravda, J. Evidence-based pathogenesis and treatment of ulcerative colitis: A causal role for colonic epithelial hydrogen peroxide. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 4263–4298 (2022).

Ismail, A., Aouaid, T., Al-Amery, M., Maulood, B., Serson, W. & B. & A preliminary study of phytochemicals in equisetum arvense and E. ramosissimum (Equisetaceae) extract from Northern Iraq. Fern Gaz. 21, 115–121 (2020).

Al-Brakati, A. et al. Possible role of Kaempferol in reversing oxidative damage, inflammation, and Apoptosis-Mediated cortical injury following cadmium exposure. Neurotox. Res. 39, 198–209 (2021).

Shiba, F., Furusho, H., Takata, T., Shimizu, R. & Miyauchi, M. Equisetum arvense Inhibits Alveolar Bone Destruction in a Rat Model with Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Periodontitis. Int. J. Dent. 1–15 (2022). (2022).

Acknowledgements

None to declare.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K., N.T., and R.S. designed the experiment. F.K. performed stereological studies. A.I. and M.M. prepared the extract. O.K. P.N., M.K. designed and performed animal experiments. A.S., R.T., P.G., and A.I. contributed to laboratory experiments, procedures, and acquisition of data. K.G. drafted the manuscript. O.K., N.T., K.G., and R.S. revised the manuscript. R.S. performed data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine-Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Permission to carry out the study was sought from the respective university administrators, and the study was conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki and was also approved by the ethics committee of the university.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koohi-Hosseinabadi, O., Koohpeyma, F., Safarpour, A.R. et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Equisetum arvense L. on acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Sci Rep 15, 13727 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97693-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97693-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Byakangelicol Alleviates Ischemic Brain Injury by Inhibiting Microglial Activation and Oxidative Stress

Molecular Neurobiology (2026)