Abstract

Current artificial intelligence (AI) trends are revolutionizing medical image processing, greatly improving cervical cancer diagnosis. Machine learning (ML) algorithms can discover patterns and anomalies in medical images, whereas deep learning (DL) methods, specifically convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are extremely accurate at identifying malignant lesions. Deep models that have been pre-trained and tailored through transfer learning and fine-tuning become faster and more effective, even when data is scarce. This paper implements a state-of-the-art Hybrid Learning Network that combines the Progressive Resizing approach and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for enhanced cervical cancer diagnostics of whole slide images (WSI) slides. ResNet-152 and VGG-16, two fine-tuned DL models, are employed together with transfer learning to train on augmented and progressively resized training data with dimensions of 224 × 224, 512 × 512, and 1024 × 1024 pixels for enhanced feature extraction. Principal component analysis (PCA) is subsequently employed to process the combined features extracted from two DL models and reduce the dimensional space of the feature set. Furthermore, two ML methods, Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) models, are trained on this reduced feature set, and their predictions are integrated using a majority voting approach for evaluating the final classification results, thereby enhancing overall accuracy and reliability. The accuracy of the suggested framework on SIPaKMeD data is 99.29% for two-class classification and 98.47% for five-class classification. Furthermore, it achieves 100% accuracy for four-class categorization on the LBC dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer has become a major global health concern, ranking among the most serious gynaecological diseases afflicting women today. This cancer develops as a result of the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the cervix, the lowest section of the uterus that connects to the vagina. According to the most recent Globo can 2022 data, there were about 661,021 new cases of cervical cancer and 348,189 deaths globally in 20221. The current incidence of this type of cancer is very high in low- and middle-income countries and thus a heavy burden on the health systems. Cervical cancer has been one of the significant issues in public health; by now, it is among the leading causes of death due to cancer in women. It has been demonstrated that early treatment significantly reduces mortality rates and improves the quality of life; thus, early detection and diagnosis are paramount to improving the results of the care of such patients2.

The conventional methods for the diagnosis of cervical cancer have included the use of Pap smear testing and HPV testing. Techniques such as these have, no doubt, been useful in diagnosing the disease; however, they are not free from their limitations concerning the accuracy and precision of the actual tests or the need for competent interpretation. On the other hand, pap smears are subject to human error and variability, and HPV testing, although successful for diagnosis of infectious involvement, does not enable any prediction of progression to malignant conditions3. Modern developments in artificial intelligence offer some very interesting solutions for these issues. AI has already been shown to be successful in changing medical diagnostics by including ML and DL-based methods that would automate complex procedures and provide sophisticated insights from huge data sets4. Systems such as these will increase diagnostic accuracy within the field of cervical cancer diagnosis with AI software to analyze medical images like Pap smear slides or HPV test outcomes5,6.

ML models can be developed, which recognize the anomalous patterns and features within medical imaging that may indicate cervix malignancy7. The DL models have an excellent capacity for extracting and analyzing complex data from images, thus improving the diagnosis of precancerous and malignancies8,9. Finally, AI-driven techniques in the analysis of patient-specific information and in the prediction of malignancy progression can help in constructing personalized treatment strategies, thereby promoting earlier intervention and focused, efficient management safeguards10,11.

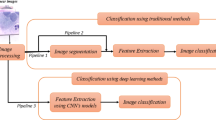

Feature-based algorithms are the principal means of accomplishing this task of computer vision technology in cervical cancer detection. Filtering techniques are first applied to image data to enhance pixel quality. Features of importance are then selected, followed by cell nucleus segmentation to extract these features. Preprocessing operations, such as removing vignetting effects, adjusting contrast, correcting pigmentation, removing stains, smoothing images, standardizing, and translating, enhance image quality and reduce noise12. Preprocessing techniques include denoising, contrast correction, image enhancement, rotation, object detection, centralization, and morphological procedures13.

Segmentation of cells and nuclei from WSI cervix images can be achieved using various approaches, such as model-based methods, thresholding, edge detection, region-based techniques, pixel-based methods, and both ML-based and DL-based strategies14,15,16. Following cell segmentation from WSI cervix slides, features are recovered to capture the image’s distinguishing characteristics, structural details, and levels of importance17,18,19,20,21,22,23. The post-processing phase is critical for improving these features since it employs techniques such as feature selection, normalization, and sparsification to identify the most relevant properties for analyzing complicated, high-dimensional datasets24,25.

The histopathological images are categorized using a variety of classification algorithms following post-processing. ML approaches such as SVM26,27,28, decision trees7,29, RF30,31,32, etc. identify intricate, high-dimensional data using engineered traits. Ensemble learning improves cervical cancer diagnosis by utilizing predictions from numerous approaches and employing strategies such as bagging, boosting, and stacking for enhanced diagnosing precision as well as reliability33,34,35,36. DL approaches, particularly CNNs, are highly useful in cervical cancer screening due to their ability to automatically extract characteristics from histopathological data, allowing for early and precise diagnosis37,38,39,40,41. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)42,43 and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)44 models are also useful for analyzing sequential data and identifying temporal trends in cancer progression.

Transfer learning optimizes cervical cancer detection rates by adapting pre-trained networks for certain databases, even with limited labeled health data. Several studies have used transfer learning with fine-tuning in cervical cancer detection to minimize computing costs and improve precision45,46,47,48,49. Feature fusion is currently becoming increasingly common in histopathological image identification for cervical cancer screening50,51. The integration of features extracted from multiple AI methods enables a more thorough and precise evaluation of the disease, leading to early diagnostic and personalized therapy regimens. Hybrid learning approaches integrate numerous algorithms for ML and DL methods to enhance diagnostic efficacy. These methods frequently integrate supervised learning algorithms, unsupervised learning, and feature extraction methods to improve the predictability and resilience of diagnostic systems. The combination of DL methods with conventional ML allows for capitalizing on the benefits of both methodologies52,53.

Usually, the first step in the analysis of Whole Slide Images (WSI) is cell segmentation, which involves identifying and isolating each cell on these medical test samples. These segmented cell visuals are then utilized to conduct classification analyses, detecting whether the cells are normal or suggest problems like malignancy. However, cell segmentation is intrinsically complex and difficult, owing to the heterogeneity in the quality and features of WSI produced in various clinical situations and test scenarios. This heterogeneity makes it challenging for one algorithm to offer consistently adequate efficacy across all settings. The WSI analysis for cancer diagnosis faces significant challenges, including the lack of detailed patch-level annotations and inconsistencies caused by variations in staining techniques. To address these issues, a dual-curriculum contrastive multi-instance learning (MIL) approach54 is introduced. The method incorporates two key strategies: saliency-guided weakly-supervised instance encoding to capture fine-grained details across different magnifications and contrastive learning to minimize label noise and redundancy. Tested on three public datasets, the approach demonstrates improved prognosis inference but faces computational challenges when handling large gigapixel WSIs. Additionally, a semi-supervision signal with Compact and Debiased Negative Embedding55 is utilized to reduce slide variability and enhance MIL algorithms. However, its effectiveness depends on the availability of normal patches, and scaling to larger datasets or more complex models remains a challenge.

In this study, a novel hybrid learning algorithm for the categorization of pap smear WSI slides is introduced to overcome these challenges. This model, which combines advanced neural systems with standard ML approaches, enhances cell classification efficacy and reliability despite the heterogeneity of WSI data. Enhanced abnormality detection allows for more effective downstream studies, which contributes to improved cervical cancer screening and early diagnostics. The key findings of the article are as follows:

-

1.

To extract deep features, Implement progressive resizing on augmented training data for training two fine-tuned DL networks, ResNet-152 and VGG-16.

-

2.

PCA is utilized to transform concatenated features into a lower-dimensional space along with a majority voting classifier based on two prominent ML algorithms, SVM and RF, to classify pap smear slides.

-

3.

The proposed model is tested using the SIPaKMeD database for 2-class (binary) and 5-class (multiclass) classification, and LBC data for 4-class (multiclass) classification.

-

4.

The suggested and baseline deep networks are evaluated using McNemar’s test, which assesses the p-value.

Experimental methods

Datasets

This study employs the publicly accessible SIPaKMeD database56, which contains 966 images of WSI pap smear slides and 4,049 cropped cell images taken with an OLYMPUS BX53F microscope and Lumenera’s INFINITY-1 camera. The dataset is classified into five categories: ‘superficial-intermediate (SI)’ and ‘parabasal (P)’ for ‘normal,’ ‘koilocytotic (K)’ and ‘dyskeratotic (D)’ for ‘abnormal,’ and ‘metaplastic (M)’ for ‘benign.’ Experiments were carried out using WSI slides, which were divided into five classes and two categories (normal and abnormal).

The framework was also evaluated using Mendeley’s liquid-based cytology (LBC) dataset available publicly57. This database includes 962 WSI LBC images that are categorized as ‘no squamous intraepithelial lesion (NILM)’ for ‘normal,’ ‘low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL),’ ‘high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL),’ and ‘squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)’ for ‘abnormal.’ The samples of each class for the data are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Preprocessing

The preprocessing procedures employed in this study, which include splitting, resizing, and augmentation of image data, are described in this section as shown in Fig. 3.

Image splitting and resizing

Images from the two datasets are reduced from 2048 × 1536 pixels to 224 × 224, 512 × 512, and 1024 × 1024 pixels for computational efficiency and compliance with DL models. After resizing, the images are divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 3:1:1 ratio: 60% for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for testing. This division encourages effective network training and evaluation.

Data augmentation

To train DL networks effectively, an extensive amount of data is required. A two-stage data augmentation procedure is used to increase the size of the training data on the scaled images. Initially, the training data is substantially augmented using an extensive pipeline that includes augmentation strategies such as Gaussian noise addition, hue and saturation changes, blurring, cropping and padding, region dropout, contrast modifications, affine transformations, etc. As shown in Table 1, this pipeline comprises 10 separate augmentation functions, each generating 10 enhanced images from the initial training sample. The ImgAug 0.4.0 library58 fully overviews these augmentation approaches.

The augmentation pipeline includes numerous operations that aim to improve image diversity and model performance. The ‘aug_func’ performs geometric translations such as rotation (-60° to 60°), shearing (-3 to 3), translation along both the x and y axes (-0.2 to 0.2), and scaling (0.7 to 1.3), which contribute to variations in image alignment and dimensions. Furthermore, horizontal and vertical flipping (probability = 1.0) is included to add diversity. The ‘canny_func’ improves edge structures by combining Canny edge detection with an alpha range of 0.6 to 0.9 and a Sobel kernel (size 2 to 8) to effectively highlight image boundaries. The ‘color_func’ modifies color attributes by changing hue and saturation (-60 to 60), shuffles color channels (probability = 1.0), and scales hue and saturation values (0.6 to 1.4). It also has K-means color reduction (5 to 15 colors) which simplifies color representation and grayscale conversion (probability = 1.0) to produce monochromatic images. The ‘sharp_func’ increases image clarity by changing lightness (0.8 to 1.4) and sharpening (alpha = 0.3 to 0.7), allowing finer features to stand out more clearly. The ‘contrast_func’ improves image contrast and brightness using linear contrast adjustments (0.8 to 1.4), brightness scaling (0.4 to 1.5), and per-channel brightness tuning (0.6 to 1.4, applied with probability 0.8). This ensures flexibility in different illumination conditions.

The ‘green_func’ selectively increases green channel intensity, adding values ranging from 20 to 90 and applying rotation (0° to 60°), which can highlight specific aspects in green-dominant images. The ‘clahe_func’ uses Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) for local contrast enhancement, with clip limits ranging from 2 to 10 and tile grid sizes from 4 to 20. Gamma contrast adjustments (1.0 to 3.0) help to manage overall brightness and contrast. The ‘blue_func’ increases blue channel intensity by adding values ranging from 20 to 90, with a rotation range of 0° to 60°, which might be useful in images where blue tones are dominating. The ‘flip_func’ adds diversity by flipping images horizontally and vertically (probability = 1.0) and using histogram equalization to improve contrast. The ‘edge_func’ is concerned with recognizing and strengthening edges through edge detection (alpha = 0 to 0.4, direction = 0.0 to 1.0) and directed edge detection (alpha = 0 to 0.4), which aids in the identification of crucial structural details. Together, these augmentation strategies increase dataset diversity, allowing the model to generalize more well across diverse imaging settings, ultimately boosting adaptability and accuracy.

After augmentation, the training set grows by a factor of 11. Tables 2 and 3 provide the updated training, validation, and test data distributions for the LBC and SIPaKMeD databases following augmentation and scaling. In addition, real-time image augmentation is performed employing the Keras library’s ‘ImageDataGenerator’ function. The above function arbitrarily modifies images, ensuring the algorithm is trained on several images for each epoch. The function’s arguments are set up as follows: zoom_range = 1.2, rotation_range = 20, horizontal_flip = True, featurewise_center = False, brightness_range = (0.4, 1.4), fill_mode = nearest, width_shift_range = 0.2, vertical_flip = True, height_shift_range = 0.2, and channel_shift_range = 20.

Methodology

The following part explains the method described in this research for analyzing cervix images to detect cancer cells. Figure 4 shows the framework of the suggested hybrid learning model.

DL-based feature extraction with transfer learning optimization and model fine-tuning

Feature extraction employing DL algorithms with transfer learning and fine-tuning is extremely efficient compared to traditional ML algorithms. DL-based feature extraction is significant as it enhances efficacy on image processing tasks by automating the extraction of intricate and hierarchical characteristics from unprocessed information. It requires less manual intervention than conventional ML, which relies on manual feature engineering4. The methodology uses ResNet-15259 and VGG-1660, two renowned DL networks, to classify cervical cancer images. Figure 5 depicts the feature maps from the distinct layers of these networks for a dataset sample image.

Given the amount of computational power needed, large data, and extended time due to processing with a GPU about the categorization of images, this makes DL in general resource-costly, reducing productivity when applied in this field. Transfer learning allows us to use models trained on related tasks so that the training time remains short while improving performance and minimizing errors61. That’s how, in computer-aided diagnostics (CAD), one common route for the transfer or adaptation of models to smaller datasets is through the transfer of knowledge from a model pre-trained on large, published datasets. Fine-tuning is the process by which the prototyped pretrained DL model gets tuned for a specific task of image classification by alternately freezing some of the layers and unfreezing the rest62. Transfer learning fine-tunes the process, making it much more efficient and accurate with small datasets, something that would otherwise take huge amounts of data and extensive retraining, all that with the features learned in the past.

This investigation uses the pre-trained weights taken from the ImageNet repository to train the DL algorithms: ResNet-152 and VGG-16. The algorithms learned previously on ImageNet are fine-tuned in this work to classify the enhanced pap-smear WSI images. The methodology involves freezing the initial layers of each model in the transfer learning step, up to ‘block4_pool’ in VGG-16 and up to ‘conv4_block18_out’ in ResNet-152, while enabling the rest of the layers for the update. Fine-tuning minimizes the number of parameters that must be trained: 7,612,933 for VGG-16 and 37,222,405 for ResNet-152, out of an overall parameter count of 15,251,269 and 60,486,533, respectively.

The DL networks integrate additional layers, such as batch normalization, dropout, global max pooling, and dense layers, which allow 1024 attributes to be extracted from each one. Figure 6 depicts the architectures of the two fine-tuned deep networks, ResNet-152 and VGG-16. The two algorithms are trained with the parameters: learning rate = 10− 4, epochs = 100 iterations, batch size = 32, and optimizer = Adam, batch size (validation and testing) = 1.

Progressive resizing

With progressive resizing, the CNN-based DL models are trained with lower-quality images first and gradually increased them to higher resolutions as training progresses. This strategy accelerates training, allowing the model to learn wider characteristics at lower resolutions before fine-tuning smaller aspects at higher resolutions, resulting in more efficient generalization and model efficacy63. Here, in this investigation, the two DL models ResNet-152 and VGG-16, are trained on three different sets of data for feature extraction. There are three datasets of progressive scaled images from the pap smear WSI data at different resolutions. The three iterations give the three iterations in which these data are located: a set of features formed at the first iteration of feature extraction in training the two DL models on datasets having resolutions of (224 × 224) pixels. This collection of features gives the base for the first level of feature extraction. The next step will then be feature extraction with the help of more advanced training data. In the set of features, transfer learning is created through the process of gradually resizing the training data from 224 × 224 pixels to 512 × 512 pixels. It is in this stage that the model can increase its potential for feature extraction by adding features from different resolutions. Third would be the feature extraction improvement using scaled data with larger dimensions: (224 × 224, 512 × 512, and 1024 × 1024) pixels. Gradually increasing the resolution would allow the model to capture and utilize finer features, thus increasing both the quality and resiliency of feature extraction in the pap smear data. Feature extraction for a given image (I) with resolution (R) can be represented as follows:

The resolution R, here is in the form R1, R2, and R3 for the three iterations, respectively. R1 is (224 × 224), R2 is (224 × 224, 512 × 512) and R3 is (224 × 224, 512 × 512, 1024 × 1024) for first, second, and third iteration respectively.

2.3.3. Feature concatenation

Feature concatenation is the process of merging multiple feature vectors side by side to create a single vector. This is often used to concatenate different data sources or feature sets. This method increases the dimensionality of the data, but it will then provide more information to the framework. Let \(\:{X}_{1}\)and \(\:{X}_{2}\) be two feature vectors defined as:

where \(\:{X}_{1}\in\:{R}^{n}\) and \(\:{X}_{2}\in\:{R}^{m}\). The concatenated feature vector \(\:{X}_{c}\) is obtained by joining \(\:{X}_{1}\) and \(\:{X}_{2}\) horizontally

where \(\:\oplus\:\) depicts the concatenation operation. The concatenated vector \(\:{X}_{c}\) will have a dimension of \(\:n+m\):

Alternatively, \(\:{X}_{c}\) can be represented element-wise as:

where

This would reflect that the first n elements of Xc come from X1 and the next m from X2. For the initial iteration, let the features f11 and f12 be extracted from the ResNet-152 and VGG-16 DL architectures. Their combined feature set shall then be denoted as f1. The vectors for the individual sets f11 and f12 are (1 × 1024) in size while that of the concatenated feature vector is (1 × 2048), which implies they are twice that length. Likewise, concatenated feature sets f2 and f3 were produced in the second iteration, as well as in the third iteration respectively.

PCA-based dimensionality reduction

PCA aims to reduce the dimensions of a large dataset while maintaining as much variability as possible. It reduces the dimensions of data by changing its original variables into a new set of variables called the principal components and correlating them in decreasing order concerning the amount of variance they capture. PCA also works very well in such applications as data visualization, noise reduction, and improving the performance of computer vision algorithms by removing redundant or irrelevant characteristics64. Moreover, it will help find out intrinsic information structure with an easy understanding of complicated datasets and find out concealed connections between variables. In PCA, the mathematical expression for converting an input feature vector (f) of size (1×m) into its principal components is given by:

Where: f= [f1, f2, …, fm] is the input feature vector with m features. W indicates the weight matrix (eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of the input data), with dimensions n × m, where n is the number of principal components selected. z = [z1, z2, …, zn] is the vector of principal components. This mapping projects the original feature vector (f) onto the new subspace defined by the principal components, thus reducing the dimensionality from m to n, where m ≤ n. In the current investigation, PCA is employed for dimensionality reduction of the concatenated feature vectors f1, f2, and f3. The reduced feature vectors are selected based on the criterion of retaining approximately 95% of the variance.

Majority voting classifier

A majority voting classifier aggregates the predictions of several different classifiers to get a final decision-making. The output class is determined by tallying the votes cast for that class. This ensemble method improves predicted performance and robustness by combining the capabilities of many models. In the proposed method, SVM and RF are used as two classifiers for predicting the class of the pap smear test set.

SVM is an approach to supervised learning utilized for regression and classification analyses. SVM seeks to identify the ideal hyperplane that divides data into classes with the greatest margin, characterized by the distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points from each class, referred to as support vectors4. For binary classification, the mathematical formulation is:

With constraint

where w is the weight vector, C is the regularization parameter, \(\xi _{i}\) are slack variables, xi is the feature vector, and yi is the class label. SVM can be expanded for multiclass classification with One-vs-Rest (OvR), which trains binary classifiers for K classes. Each classifier generates a score, and the class with the highest score is chosen.

Here, wk and bk are the weight vector and bias for class k.

RF is an ensemble learning technique that builds several decision trees throughout training and provides the mean prediction (for regression) or the mode of the groups (for classification) of each tree. It improves prediction precision and resilience by aggregating the findings of numerous trees, reducing overfitting problems inherent in single decision trees7. Mathematically, the best possible prediction is determined by the majority vote across all trees. The prediction for the t-th tree is given by:

For binary class, the prediction of the RF classifier is:

Where T indicates the total number of trees, and mode represents the most common class name among the trees.

The RF algorithm predicts its output for multiclass classification:

Here, 1(\(\:\widehat{{y}_{\text{t}}}=\text{k}\)) is an indicator function that returns 1 if the t-th tree predicts class k and 0 otherwise. The class k with the most votes will be the final predicted outcome.

A majority voting classifier aggregates the outputs of the two classifiers to integrate predictions made by SVM and RF algorithms. Let \(\:{\widehat{\text{y}}}_{SVM}\) and \(\:{\widehat{\text{y}}}_{RF}\) be the prediction from the SVM and RF classifiers. The final prediction \(\:{\widehat{\text{y}}}_{Majority}\) is obtained by combining the predictions of the two separate classifiers. It can be expressed for k-classes as:

Consider \(\:{Votes}_{k}\) here is the number of classifiers that vote for class (k). The idea is to count, for every classifier, how many votes it has given to some particular class in SVM and RF, and then select the class with maximum votes.

Results and implications

Experimental setup

The proposed framework is developed on a Windows 10 machine equipped with an Nvidia Tesla V100 graphics processor and 16 GB of GPU memory. All the exploratory activities were conducted within the Python 3.7 programming environment, exposing an exhaustive list of libraries and tools. The solution of ML tasks will be done using Scikit-learn 1.3.2, while for algorithms of DL, will be using TensorFlow 2.13.1 with Keras 2.14.0. It also is powered by CUDA together with cuDNN for GPU acceleration, NumPy for numerical computations, and Matplotlib for data visualization. Such a system can be stable and flexible for building, training, and evaluating models.

Evaluation metrics

The classifier’s efficiency has to be cross-checked with another category of measures, to find a measure that acts more efficiently. More precisely, major measures like precision, sensitivity, accuracy, and F-score give different insights into the working order of the proposed framework in the present research study65. Precision is defined as the likelihood of forecasting positive. Sensitivity is a measure of the rate of actual positive cases compared with all cases that are predicted to be positive. This is such an important statistic, maybe the most important, when the false-positive rate is high. Sensitivity is the same as recall and measures how well the model finds the true positive cases. This measure computes the average positive example correctly identified to the total required positives. It suggests how well the algorithm is capturing the positive scenarios. Percent accuracy is the proportion of totally correctly predicted cases concerning the total number of cases. This gives an overview of how well the classifier has worked within each category. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is a robust metric used to assess binary classification performance, particularly in imbalanced datasets. It ranges from − 1 to + 1, where + 1 means perfect predictions, 0 reflects random guessing, and − 1 signifies entirely incorrect predictions. The F-score is a measure of performance that hence covers a compromise between precision and sensitivity. This is one of the very useful statistics through which one can be presented with a well-balanced view regarding the efficacy of the classifier, more so in cases where the consequences of making wrong and right predictions of positives and negatives are high.

Here, \(\:{P}_{true}\) = True Positive, \(\:{N}_{true}\) = True Negative, \(\:{P}_{false}\) = False Positive, \(\:{N}_{false}\) = False Negative

Results

This section discusses in detail the experimental results obtained from the testing of the SIPaKMeD WSI slides and LBC WSI images. In this respect, testing results for two baseline deep learning algorithms (ResNet-152 and VGG-16) and the proposed framework have been employed, considering their performance individually to evaluate the proposed algorithm’s efficiency. Each model is experimented with in three iterations: Iteration 1 with a resolution of 224 × 224, Iteration 2 with resolutions of 224 × 224 and 512 × 512, and Iteration 3 with resolutions of 224 × 224, 512 × 512, and 1024 × 1024. The confusion matrices for binary and multiclass classification of the SIPaKMeD dataset in iterations 1, 2, and 3 are shown correspondingly in Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. In Tables 4 and 5, there are classification results for the SIPaKMeD data in the 5-class and 2-class cases correspondingly. These tables show the efficiency of the classification algorithms and the proposed Hybrid Learning method. All three iterations are compared with the fine-tuned versions of ResNet-152 and VGG-16. The implemented framework performs well, with an accuracy score of 98.47% in the 5-class categorization and 99.29% in the 2-class assignments. The model achieves a precision of 98.72%, sensitivity of 98.97%, and F-score of 98.82% in accurately classifying cervix images in the 5-class classification. In the 2-class classification, the model outperforms all other classifiers, with a precision of 98.92%, a sensitivity of 100%, and an F-score of 99.46%.

Furthermore, the proposed approach was tested using the LBC WSI image database. Figures 13, 14 and 15 show the confusion matrices for Iterations 1, 2, and 3, allowing us an illustration of the model’s efficiency across each iteration on the LBC data. Table 6 shows a comprehensive performance assessment of the suggested model alongside the baseline classifiers, ResNet-152 and VGG-16. Notably, the suggested technique achieved excellent classification by accurately identifying all test images in the data set. These results demonstrate how well the suggested method handles a range of classification challenges due to its resilience and predictability.

Performance comparison

Table 7 shows a comparison of the proposed method with the most recent studies in the literature for 5-class and 2-class classification of SIPaKMeD WSI slides. This assessment will facilitate the knowledge of the position of the framework under development, as well as the other state-of-the-art techniques within the field, and will clearly render the baseline of its performance. However, Table 8 presents the class-wise performance of the proposed model against LBC WSI data for adaptability. The similar results of the comparisons have firm implications for the validity and reliability of the ability to categorize cervical cancer cases properly. Such findings indicate that the model could be used in enhancing the effectiveness or competence of cervical cancer diagnosis.

On the other side, a limitation may arise from the need for pre-training DL models, since said models are not reported to be soundly adjusted for the medical image features, with derived features being hence inaccurately computed. Transfer learning of pre-trains, along with fine-tuning, is applied in the development of cervical cancer detection tasks and enhancements of model capacity to a great extent in feature recognition. Though this is not an explicit problem, it is rather a very important computational demand of the strategy. The other approach allows for progressive resizing, but at the cost of amortizing the computational demand of feature extraction and modulating the rise of computing needs that increased quality images result in when choosing this technique used during training.

McNemar’s analysis

The McNemar Test is crucial for assessing the efficacy of a hybrid learning model to baseline DL algorithms, especially when both models are applied to the same dataset. The statistical examination is specifically developed to determine whether observed variations in model efficacy are statistically significant, with an emphasis on scenarios when the models produce different results for the same data points. Table 9 shows the p-value computed employing McNemar’s analysis for the proposed hybrid learning framework and the two originating classifiers, ResNet-152 and VGG-16. If the obtained p-value is less than 0.05, it means that the suggested framework and the baseline classifiers are substantially distinct in their feature extraction abilities. All computed p-values for both sets of data are less than this threshold, thereby the null hypothesis is ruled out, demonstrating the suggested algorithm outperforms the baseline DL algorithms. This analysis demonstrates the efficacy and validity of our suggested approach for categorizing pap-smear WSI slides.

Conclusion and future work

This paper implements a Hybrid Learning Network which employs Progressive Resizing and PCA approach for enhanced cervical cancer screening with WSI data. The system optimizes feature extraction from augmented images of varying resolutions by combining DL networks, ResNet-152 and VGG-16, with transfer learning and fine-tuning. PCA lowers dimensionality, and the consequent features are analyzed by SVM and RF algorithms, with final predictions combined via majority voting. The framework has high accuracy rates, including 99.29% for two-class and 98.47% for five-class classifications on SIPaKMeD data, as well as 100% for four-class classification on the LBC dataset, indicating its efficacy and robustness. These improved detection capabilities lay the foundation for a more extensive and intelligent examination of the WSI image data. Future research will concentrate on integrating more advanced feature selection approaches, which will aid in selecting the most appropriate characteristics while reducing dimensionality, ultimately enhancing model efficiency and reducing computational costs. In addition, we intend to investigate progressive ensemble techniques, which entail sequentially merging multiple frameworks or algorithms to capitalize on their respective capabilities.

Data availability

This study includes two publicly accessible cervical cancer WSI datasets: (a) SIPaKMeD Pap Smear database available at https://www.cs.uoi.gr/~marina/sipakmed.html. (b) LBC dataset available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/zddtpgzv63/4. The code developed for data processing and analysis in this research is available at GitHub. (https://github.com/nitinchauhan7201/HDL-Progressive-Resizing-and-PCA-for-Cervical-Cancer-Detection).

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural networks

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- WSI:

-

Whole slide images

- GPU:

-

Graphics processing unit

- SI:

-

Superficial-intermediate

- P:

-

Parabasal

- K:

-

Koilocytes

- D:

-

Dyskeratotic

- M:

-

Metaplastic

- NILM:

-

No Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

- LSIL:

-

Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

- SCC:

-

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- HSIL:

-

High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263 (2024).

Kassa, R. N., Shifti, D. M., Alemu, K. & Omigbodun, A. O. Integration of cervical cancer screening into healthcare facilities in low-and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLOS Global Public. Health. 4 (5), e0003183. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003183 (2024).

Gavinski, K. & DiNardo, D. Cervical cancer screening. Med. Clin. 107 (2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2022.10.006 (2023).

Chauhan, N. K. & Singh, K. A review on conventional machine learning vs deep learning. In 2018 International conference on computing, power and communication technologies (GUCON) (pp. 347–352). https://doi.org/10.1109/GUCON.2018.8675097 (IEEE, 2018).

Egemen, D. et al. Artificial intelligence–based image analysis in clinical testing: lessons from cervical cancer screening. JNCI: J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 116 (1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djad202 (2024).

Vargas-Cardona, H. D. et al. Artificial intelligence for cervical cancer screening: scoping review, 2009–2022. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 165 (2), 566–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.15179 (2024).

Chauhan, N. K. & Singh, K. Performance assessment of machine learning classifiers using selective feature approaches for cervical cancer detection. Wireless Pers. Commun. 124 (3), 2335–2366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-022-09467-7 (2022).

Youneszade, N., Marjani, M. & Pei, C. P. Deep learning in cervical cancer diagnosis: architecture, opportunities, and open research challenges. IEEE Access. 11, 6133–6149. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3235833 (2023).

Moldovanu, S., Tăbăcaru, G. & Barbu, M. Convolutional neural Network–Machine learning model: hybrid model for meningioma tumour and healthy brain classification. J. Imaging. 10 (9), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging10090235 (2024).

Ghaffar Nia, N., Kaplanoglu, E. & Nasab, A. Evaluation of artificial intelligence techniques in disease diagnosis and prediction. Discover Artif. Intell. 3 (1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-023-00049-5 (2023).

Juneja, M., Saini, S. K., Kaur, H. & Aggarwal, N. Computer-Aided diagnosis system for early detection of malignant tissues. In Molecular Biomarkers for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy (63–80). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3746-2_5 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Advances in data preprocessing for biomedical data fusion: an overview of the methods, challenges, and prospects. Inform. Fusion. 76, 376–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.07.001 (2021).

Robert, P. & Kavida, A. C. Morphological-based medical image processing on cervical cytology cancer images using connected component techniques. Curr. Med. Imaging. 17 (12), 1439–1450. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573405617666210707161945 (2021).

Sarwar, A., Sheikh, A. A., Manhas, J. & Sharma, V. Segmentation of cervical cells for automated screening of cervical cancer: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 2341–2379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-019-09735-2 (2020).

Hayakawa, T., Prasath, V. S., Kawanaka, H., Aronow, B. J. & Tsuruoka, S. Computational nuclei segmentation methods in digital pathology: a survey. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 28, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-019-09366-4 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Segmentation of acetowhite region in uterine cervical image based on deep learning. Technol. Health Care. 30 (2), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-212890 (2022).

Jia, A. D., Li, B. Z. & Zhang, C. C. Detection of cervical cancer cells based on strong feature CNN-SVM network. Neurocomputing 411, 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2020.06.006 (2020).

Diniz, D. N. et al. A hierarchical feature-based methodology to perform cervical cancer classification. Appl. Sci. 11 (9), 4091. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11094091 (2021).

Yaman, O. & Tuncer, T. Exemplar pyramid deep feature extraction based cervical cancer image classification model using pap-smear images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 73, 103428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103428 (2022).

Kalbhor, M. M. & Shinde, S. V. Cervical cancer diagnosis using Convolution neural network: feature learning and transfer learning approaches. Soft. Comput. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-08969-1 (2023).

Kurman, S. & Kisan, S. An in-depth and contrasting survey of meta-heuristic approaches with classical feature selection techniques specific to cervical cancer. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 65 (5), 1881–1934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10115-022-01825-y (2023).

Munshi, R. M. Novel ensemble learning approach with SVM-imputed ADASYN features for enhanced cervical cancer prediction. PLoS One. 19 (1), e0296107. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296107 (2024).

Liaw, L. C. M., Tan, S. C., Goh, P. Y. & Lim, C. P. Cervical cancer classification using sparse stacked autoencoder and fuzzy ARTMAP. Neural Comput. Appl. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-09706-x (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Cervical cancer detection using K nearest neighbor imputer and stacked ensemble learning model. Digit. Health. 9, 20552076231203802. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231203802 (2023).

Ergul Aydin, Z. & Kamisli Ozturk, Z. Filter-based feature selection methods in the presence of missing data for medical prediction models. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83 (8), 24187–24216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-15917-6 (2024).

Win, K. P., Kitjaidure, Y., Hamamoto, K. & Myo Aung, T. Computer-assisted screening for cervical cancer using digital image processing of pap smear images. Appl. Sci. 10 (5), 1800. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10051800 (2020).

He, S., Xiao, B., Wei, H., Huang, S. & Chen, T. SVM classifier of cervical histopathology images based on texture and morphological features. Technol. Health Care. 31 (1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-220031 (2023).

Munshi, R. M. Novel ensemble learning approach with SVM-imputed ADASYN features for enhanced cervical cancer prediction. PLoS One. 19 (1), e0296107. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11070729 (2024).

Narayan, S. R. & Rose, R. J. Cervical cancer detection based on novel decision tree approach. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 44 (2). https://doi.org/10.32604/csse.2023.022564 (2023).

Chauhan, N. K. & Singh, K. Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer with Oversampled Unscaled and Scaled Data Using Machine Learning Classifiers. In 2022 IEEE Delhi Section Conference (DELCON) (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/DELCON54057.2022.9753298 (IEEE, 2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Construction of a diagnostic classifier for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer based on XGBoost feature selection and random forest model. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 49 (1), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.15458 (2023).

Devi, S., Gaikwad, S. R. & Harikrishnan, R. Prediction and detection of cervical malignancy using machine learning models. Asian Pac. J. cancer Prevention: APJCP. 24 (4), 1419. https://doi.org/10.31557%2FAPJCP.2023.24.4.1419 (2023).

Karamti, H. et al. Improving prediction of cervical cancer using Knn imputed Smote features and multi-model ensemble learning approach. Cancers 15 (17), 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15174412 (2023).

Bhavani, C. H. & Govardhan, A. Cervical cancer prediction using stacked ensemble algorithm with SMOTE and RFERF. Mater. Today Proc. 80, 3451–3457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.269 (2023).

Aljrees, T. Improving prediction of cervical cancer using KNN imputer and multi-model ensemble learning. Plos One. 19 (1), e0295632. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295632 (2024).

Ali, M. S., Hossain, M. M., Kona, M. A., Nowrin, K. R. & Islam, M. K. An ensemble classification approach for cervical cancer prediction using behavioral risk factors. Healthc. Analytics. 5, 100324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.health.2024.100324 (2024).

Kiran, G. V. & Meghana Reddy, G. K., Automatic classification of whole slide pap smear images using CNN with PCA based feature interpretation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (pp. 1074–1079). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2019.00140 (2019).

Chauhan, N. K. & Singh, K. Impact of variation in number of channels in CNN classification model for cervical cancer detection. In 2021 9th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions)(ICRITO) (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRITO51393.2021.9596366 (IEEE, 2021).

Pacal, I. & Kılıcarslan, S. Deep learning-based approaches for robust classification of cervical cancer. Neural Comput. Appl. 35 (25), 18813–18828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08757-w (2023).

Sarhangi, H. A., Beigifard, D., Farmani, E. & Bolhasani, H. Deep learning techniques for cervical cancer diagnosis based on pathology and colposcopy images. Inf. Med. Unlocked. 101503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2024.101503 (2024).

Chitra, B., Kumar, S. S. & Subbulekshmi, D. Prediction models applying convolutional neural network based deep learning to cervical cancer outcomes. IETE J. Res. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2024.2305831 (2024).

Thakur, T. et al. RNN-CNN based cancer prediction model for gene expression. IEEE Access. 11, 131024–131044. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3332479 (2023).

Farhan, H. R., Kod, M. S., Taqi, A. & Ghazi, S. A. Ovarian cancer detection based on Elman recurrent neural network. Periodica Polytech. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPee.23081 (2024).

Jeyshri, J. & Kowsigan, M. Multi-stage Attention-Based long Short-Term memory networks for cervical cancer segmentation and severity classification. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 48 (1), 445–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40998-023-00664-z (2024).

Wang, R., Armin, M. A., Denman, S., Petersson, L. & Ahmedt-Aristizabal, D. Towards interpretable attention networks for cervical cancer analysis. In 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) (pp. 3613–3616). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9629604 (IEEE, 2021).

Chauhan, N. K., Singh, K., Namdeo, S. & Muley, A. An evaluative investigation of deep learning models by utilizing transfer learning and fine-tuning for cervical cancer screening of whole slide Pap-smear images. In 2023 7th International Conference on Computer Applications in Electrical Engineering-Recent Advances (CERA) (pp. 1–5). https://doi.org/10.1109/CERA59325.2023.10455623 (IEEE, 2023).

Allogmani, A. S., Mohamed, R. M., Al-Shibly, N. M. & Ragab, M. Enhanced cervical precancerous lesions detection and classification using Archimedes optimization algorithm with transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 12076. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62773-x (2024).

Ali, A. H. & Abdulazeez, A. M. Transfer learning in machine learning: A review of methods and applications. Indonesian J. Comput. Sci. 13 (3). https://doi.org/10.33022/ijcs.v13i3.4068 (2024).

Panda, M., Dehuri, P., Mohapatra, D. & Pandey, A. K. Diagnostic utility of transfer learning by using convolutional neural network for cytological diagnosis of malignant effusions. Diagn. Cytopathol. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.25382 (2024).

Hamdi, M. et al. Analysis of WSI images by hybrid systems with fusion features for early diagnosis of cervical cancer. Diagnostics 13 (15), 2538. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13152538 (2023).

Chauhan, N. K., Singh, K., Kumar, A. & Kolambakar, S. B. HDFCN: A robust hybrid deep network based on feature concatenation for cervical cancer diagnosis on WSI pap smear slides. Biomed. Res. Int. 2023(1), 4214817. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4214817 (2023).

Kalbhor, M., Shinde, S., Joshi, H. & Wajire, P. Pap smear-based cervical cancer detection using hybrid deep learning and performance evaluation. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomedical Engineering: Imaging Visualization. 11 (5), 1615–1624. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681163.2022.2163704 (2023).

Attallah, O. Cervical cancer diagnosis based on multi-domain features using deep learning enhanced by handcrafted descriptors. Appl. Sci. 13 (3), 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031916 (2023).

Tu, C., Zhang, Y. & Ning, Z. Dual-curriculum contrastive multi-instance learning for cancer prognosis analysis with whole slide images. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 29484–29497 (2022).

Lee, J., Nam, H., Lee, K. & Hahn, S. Compact and De-Biased Negative Instance Embedding for Multi-Instance Learning on Whole-Slide Image Classification. In ICASSP 2024–2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 2350–2354). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10448245 (IEEE, 2024).

Plissiti, M. E. et al. Sipakmed: A new dataset for feature and image based classification of normal and pathological cervical cells in pap smear images. In 2018 25th IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP) (pp. 3144–3148). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2018.8451588 (IEEE, 2018).

Hussain, E., Mahanta, L. B., Borah, H. & Das, C. R. Liquid based-cytology Pap smear dataset for automated multi-class diagnosis of pre-cancerous and cervical cancer lesions. Data brief. 30, 105589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.105589 (2020).

Jung, A. B. et al. imgaug. Online. https://github.com/aleju/imgaug. Accessed 18-Jan-2024. (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 770–778). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (2016).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:1409.1556. (2014).

Kim, H. E. et al. Transfer learning for medical image classification: a literature review. BMC Med. Imaging. 22, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-022-00793-7 (2022).

Iman, M., Arabnia, H. R. & Rasheed, K. A review of deep transfer learning and recent advancements. Technologies 11 (2), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies11020040 (2023).

Gogoi, M. & Begum, S. A. Progressive 3-layered block architecture for image classification. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 13(3). (2022).

Kherif, F. & Latypova, A. Principal component analysis. In Machine learning. 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815739-8.00012-2 (Academic Press, 2020).

Hicks, S. A. et al. On evaluation metrics for medical applications of artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 5979. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09954-8 (2022).

Hardatin, R., Muslimah, M. N. & Hasanah, S. N. Perbandingan Arsitektur ResNet50 Dan ResNet101 Dalam Klasifikasi Kanker Serviks Pada citra pap smear. Faktor Exacta. 14 (3), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.30998/faktorexacta.v14i3.10010 (2021).

Manna, A., Kundu, R., Kaplun, D., Sinitca, A. & Sarkar, R. A fuzzy rank-based ensemble of CNN models for classification of cervical cytology. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 14538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93783-8 (2021).

Karim Kutty, S. & Chandrasekhara Menon, G. Enhancing convolutional neural network model with spectral features for the identification of cervical dysplasia. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 32 (6), 1916–1927. https://doi.org/10.1002/ima.22740 (2022).

Yadav, A., Ahmed, F., Daescu, O., Gedik, R. & Coskunuzer, B. Histopathological Cancer Detection with Topological Signatures. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) (pp. 1610–1619). https://doi.org/10.1109/BIBM58861.2023.10385822 (IEEE, 2023).

Khanarsa, P. & Kitsiranuwat, S. Deep learning-based ensemble approach for conventional pap smear image classification. ECTI Trans. Comput. Inform. Technol. (ECTI-CIT). 18 (1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.37936/ecti-cit.2024181.254621 (2024).

Zhao, C., Shuai, R., Ma, L., Liu, W. & Wu, M. Improving cervical cancer classification with imbalanced datasets combining taming Transformers with T2T-ViT. Multimedia Tools Appl. 81 (17), 24265–24300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-12670-0 (2022).

Attallah, O. CerCan· net: cervical cancer classification model via multi-layer feature ensembles of lightweight CNNs and transfer learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 229, 120624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120624 (2023).

Das, N., Mandal, B., Santosh, K. C., Shen, L. & Chakraborty, S. Cervical cancerous cell classification: opposition-based harmony search for deep feature selection. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet. 14 (11), 3911–3922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-023-01872-z (2023).

Pacal, I. MaxCerVixT: A novel lightweight vision transformer-based approach for precise cervical cancer detection. Knowl. Based Syst. 289, 111482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111482 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chauhan, N.K., Singh, K., Kumar, A. et al. A hybrid learning network with progressive resizing and PCA for diagnosis of cervical cancer on WSI slides. Sci Rep 15, 12801 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97719-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97719-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sensor-Driven PCA–DEA framework for efficiency optimization in manual material handling: application to industrial purification systems with ergonomic redesign validation

Production Engineering (2026)

-

WHFDL: an explainable method based on World Hyper-heuristic and Fuzzy Deep Learning approaches for gastric cancer detection using metabolomics data

BioData Mining (2025)

-

A hybrid vision transformer with ensemble CNN framework for cervical cancer diagnosis

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2025)

-

A hybrid compound scaling hypergraph neural network for robust cervical cancer subtype classification using whole slide cytology images

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Advancements in fusion-based deep representation learning for enhanced cervical precancerous lesion classification using biomedical image analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)