Abstract

In the urbanization process, phenomena such as the urban heat island effect exacerbate climatic deteriorations, leading to environmental issues in cities. Campus areas, as significant ecological components within the urban environment, play a crucial role in environmental regulation. This paper investigates the impact of outdoor physical environments in campuses on users’ thermal comfort from the perspective of thermal comfort. Using surveys, meteorological measurements, and behavioral analysis, this study examines four distinctive spaces within a campus in Xi’an, establishing a thermal comfort baseline for the population in Xi’an’s campus spaces. The research results indicate: (1) Globe temperature (Tg), air velocity (Va), air temperature (Ta), and ground temperature (G) are the primary factors affecting students’ thermal sensations in campus open spaces. Respondents tended to improve their thermal sensations through changes in humidity and solar radiation. (2) In the campus open spaces of Xi’an, the overall NPET of the subjects was 13.9 °C, with the NPETR ranging from 9.4 to 18.4 °C. (3) The preferred warmth temperature for university students in Xi’an is 15.15 °C, which is 1.25 °C higher than the NPET (13.9 °C).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the urbanization process, ecological environments change due to human activities, leading to urban environmental issues such as the urban heat island effect, urban dry island effect, and deterioration of local microclimates1,2,3,4. The degradation of the ecological environment, characterized by extreme temperatures and other adverse environmental conditions, exposes urban residents to physical environments unsuitable for living and working5. Extreme weather temperatures cause heat stress in humans, leading to increased rates of hospitalization and mortality. Numerous studies have shown that direct solar radiation significantly affects human thermoregulation6,7,8,9. Research by Li et al. found that the mean radiant temperature (Tmrt) outdoors is greatly influenced by solar radiation directly hitting the skin, making the thermal sensation of being outdoors in sunlight differ by one thermal sensation10 level from the same temperature indoors. As a significant ecological entity within the urban environment, campus areas have a strong capability to regulate the environment. Vegetation in campus outdoor spaces can reduce temperatures by 70% through transpiration11 and absorb 80% of solar radiation12.

Students are the main users of campus open spaces, and a well-maintained open campus environment promotes their physical and mental health development. Studies indicate that collaboration and group projects are increasingly valued, and students often complete related tasks outside the classroom, a behavior defined as “informal learning.” Campus open spaces are one of the preferred areas for students to engage in informal learning activities13. The environment of open spaces in universities can effectively alleviate student fatigue, thereby enhancing cognitive abilities14. The design of open spaces significantly impacts students’ experiences. Comfortable open spaces improve the recovery of physical functions and psychological fatigue during breaks between classes, thereby enhancing their performance in class15 and achieving better social interactions16. Open spaces provide venues for physical activities and recreation, helping to alleviate the negative emotions associated with daily academic stress17,18. Additionally, Sun et al. found that students’ thermal perception levels vary throughout the day19, although their study focused only on thermal perception changes inside classrooms and overlooked the consideration of campus open space activities as part of students’ heat adaptation behaviors.

This paper aims to investigate the impact of the outdoor physical environment in campuses on users’ thermal comfort from a thermal comfort perspective. These main aspects greatly influence overall comfort conditions and can be optimized through active and passive solutions for campus open spaces. Our study selected four typical spaces in a campus in Xi’an, a cold region of China (outdoor area in front of Wen-Zhi College, basketball court beside Wen-Zhi College, beside the Tengfei Tower pool, and south side plaza of the main building), each with different substrate characteristics that influence the outdoor thermal environment, such as reflectivity and evaporation rates20,21,22,23.

The objectives of this study are to: (1) Identify the main factors affecting students’ thermal sensations during outdoor activities; (2) Analyze the spatiotemporal distribution of the population in campus open spaces; (3) Establish an outdoor thermal comfort baseline for campus open spaces based on thermal comfort and thermal sensation voting; (4) Propose optimization strategies for campus open spaces to create a favorable outdoor thermal comfort environment for the primary user group. The results of this study will provide data support for enhancing and remodeling outdoor thermal comfort in campuses and serve as a reference for constructing outdoor thermal environments in campuses worldwide at similar latitudes.

Methods

Study location

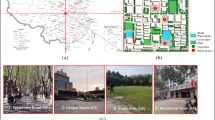

The research team conducted outdoor surveys in a university campus in Xi’an, China (longitude 108.98°E, latitude 34.25°N) (Fig. 1), and the base map was obtained from Google Maps (Imagery2025 Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Map data 2025). The campus covers an area of 1946 acres with a built-up area of 1.755 million square meters. We selected four typical outdoor spaces on campus, based on surface conditions, from the areas with the highest pedestrian flow: (A) the outdoor area in front of the Wen-Zhi Academy, (B) the basketball court adjacent to Wen-Zhi Academy, (C) the poolside area near the Tengfei Tower, and (D) the plaza to the south of the main building. Among these, space A features a large area of cement flooring; space B has a basketball court with a plastic flooring surface; space C includes a large water feature and greenery; and space D has a plaza with a brick-paved surface. These different surface materials are typical representatives of campus construction in China.

Experimental design

This experiment includes four typical areas within the campus. Investigators simultaneously collected survey questionnaires in these four typical areas of the campus. Considering the possibility of individual differences affecting the participants’ thermal perception, surveyors conducted random questionnaire surveys at designated locations to determine the participants’ perception of outdoor climate conditions and thermal sensations. Before administering the questionnaire, the surveyor explained the purpose, methods, and procedures of the study to each participant. The survey collected the immediate subjective feelings of the participants, who were asked to spend 15 min familiarizing themselves with their surroundings at designated locations before filling out the questionnaire. During the survey, the surveyors also recorded air temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), wind speed (m/s), globe temperature (°C), and solar radiation (W/m2).

Meteorological measurements

The field study of this experiment started on March 5, 2023, and continued until April 16, 2023. Collected meteorological parameters include air temperature (Ta), globe temperature (Tg), relative humidity (RH), wind speed (Va), and solar radiation (G). Ta, Tg, and Va are used in Eq. (1) to calculate the mean radiant temperature (Tmrt). In Eq. (1), D represents the diameter of the globe, which is 0.07 m in this study. The variable ε represents the emissivity, which is set at 0.95 for a black globe.

The choice of instruments complies with ISO 7726 standards. Four meteorological stations were established in four typical outdoor spaces, with meteorological data recorded simultaneously at each station. All instruments were installed at a height of 1.5 m above the ground and recorded data every 1 min. Temperature values were tested using the JT2020 multifunctional tester (temperature and humidity sensor). Data recording avoided extreme weather conditions such as rain, snow, or strong winds. The specific measurement instruments are shown in Table 1.

Questionnaire survey

The questionnaire consists of three parts. The first part collects personal information, including gender, age, ethnicity, clothing, local residency history, types of clothing worn, and activity level. The clothing insulation was referenced from ASHRAE Standard 55 and ISO 7726 standards. The second part of the questionnaire investigates the participants’ subjective sensations, including Thermal Sensation Vote (TSV) and Thermal Comfort Vote (TCV). The participants’ sensation votes are recorded using the ASHRAE 7-point sensation scale, and comfort votes are marked using a 7-point scale24. The third part of the questionnaire is filled out by the surveyors, noting the ambient air temperature (Ta), globe temperature (Tg), relative humidity (RH), wind speed (Va), and solar radiation (G) at the time of the survey.

Index calculation and statistical analysis

The Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) was used as a thermal index25. The Rayman model was utilized for evaluating thermal comfort26,27,28. Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) is used to describe the subjective perception of the environment by the human body. It takes into account various environmental meteorological factors to more accurately reflect the thermal sensation of the environment. We use RayMan for analysis and calculation, collecting information such as air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, clothing thermal resistance, activity intensity, and globe temperature, to determine the PET value for each respondent. Based on the meteorological parameters detected in the questionnaire survey, the mean Thermal Sensation Vote (TSV) for each 1 °C of PET was calculated to obtain the Mean Thermal Sensation Vote (MTSV). Subsequently, linear regression analysis was conducted to solve the equation. This linear regression model was used to determine the corresponding temperatures at specific points, categorizing PET into seven stress levels29. We will obtain the NPET through linear fitting and perform statistical analysis on the NPETR to identify the most comfortable temperature range for volunteers in the campus open spaces in this study.

Human subject research

This research was granted ethical approval for medical and biological scientific research by the Ethics Committee of the Honghui Hospital affiliated to Xi’an Jiaotong University. A recruitment activity for human participants was carried out, with the recruitment period spanning from March 5, 2023 to April 16, 2023. All participants provided informed consent.

The research objects and methods of this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Basic information of respondents

In this study, we conducted field research with 901 volunteers and obtained 820 valid responses. The majority of the volunteers were students, accounting for 87.8% of the valid data. The remaining volunteers included faculty members and individuals from outside the campus. All volunteers had lived in Xi’an for more than one year.

Meteorological parameters

Among the four measurement locations, Location D had the highest average Ta at 22.7 °C, while the lowest average Ta was recorded at Location A at 20.3 °C. Due to the presence of a water body near Location C, it had the highest average RH at 50.6%. The spatial configuration of all measurement points being open spaces, and their similar spatial forms, resulted in minimal differences in Va and G across locations (Table 2).

Thermal sensation voting (TSV) and thermal comfort voting (TCV)

Figures 2; Table 3 display the TSV and TCV votes of students, respectively. Among the respondents, 38.5% felt “Neutral” (TSV = 0), with the highest proportion in TCV also being “Neutral” (55.6%). This was followed by “Slightly Comfortable” (TCV = 1) accounting for 23%, and “Slightly Uncomfortable” (TCV=-1) at 2.5%. Respondents feeling “Slightly Cold” (TSV=-1) made up 12.4%, with the highest proportion again for “Neutral” (TCV = 0) at 34.2%, “Slightly Uncomfortable” (TCV=-1) at 24.6%, and “Slightly Comfortable” (TCV = 1) at 23.6%. Those feeling “Slightly Hot” (TSV = 1) comprised 20.7%, with “Slightly Comfortable” (TCV = 1) being the majority at 39.4%, “Neutral” (TCV = 0) at 31.5%, and “Slightly Uncomfortable” (TCV=-1) at 12.1%. The statistical results indicate that respondents’ thermal sensations in the test environment were concentrated around neutral, and respondents preferred a slightly warmer environment.

Meteorological factor preference voting

Among these sites, respondents showed more distinct preferences for humidity and solar radiation, while most wished for temperature and wind speed to remain at their original levels. In the preference votes across the four sites, more respondents in Space A preferred a higher temperature (20.1%) compared to the other three spaces. Due to the higher activity level of respondents in Space B, more people preferred lower temperatures (27.1%) and solar radiation (39.8%), and higher wind speed (23.8%). Additionally, a larger proportion of respondents in Space A preferred higher humidity (40.4%) compared to the other three spaces, while Space C, which has water bodies for microclimate regulation, displayed more stable preference votes for all four meteorological factors.

Physical variables and TSV

Meteorological parameters vary across spaces and can directly or indirectly affect people’s perception of the thermal environment. To further explore the extent to which each meteorological parameter influences the respondents’ thermal sensation voting, we employed Spearman correlation analysis to analyze the relationship between physical variables and TSV. Our calculations revealed that in spring, the respondents’ thermal sensations showed no statistically significant correlation with humidity, clothing insulation, and activity type. The globe temperature had the most significant impact on the thermal sensation of college students outdoors (R2 = 0.964**), while there was also a significant positive correlation with air temperature (R2 = 0.821*), wind speed (R2 = 0.857*), and solar radiation had a significant but relatively weaker impact (R2 = 0.786*) (Table 4).

Respondents’ behavioral posture and activity intensity

During the survey, we conducted a statistical analysis of the activities recently performed by the respondents, based on their behavioral posture and activity intensity. The detailed statistics are presented in Table 5.

In this study, field surveys were conducted in four typical spaces within the campus of a university in Xi’an, a cold region of China. The spaces included: (A) the outdoor area in front of the Wen-Zhi Academy, (B) the basketball court adjacent to Wen-Zhi Academy, (C) the poolside area near the Tengfei Tower, and (D) the plaza to the south of the main building. Meteorological measurements were taken concurrently with a questionnaire survey targeting university students regarding their activities within the campus over the past 20 min. Specifically, 244 questionnaires were collected at location A, 181 at location B, 108 at location C, and 287 at location D. Most volunteers were students from the campus and had lived in Xi’an for more than one year.

Regarding time, the data from all respondents were divided into three categories: data collected from 6:00 to 12:00 were classified under the “Morning” group, with 135 valid responses; from 12:00 to 18:00 under the “Afternoon” group, with 569 valid responses; and from 18:00 to 23:00 under the “Evening” group, with 116 valid responses, totaling 820 responses. In the morning survey: Space D had the highest proportion of data collected, with a total of 99 responses, accounting for 73.3% of the total data for the morning period. Spaces A and B had the least data, each with 8 responses, accounting for 5.9% of the total morning data. In the afternoon survey: Space A had the most data, with 201 responses, accounting for 35.3% of the total afternoon data. Space C had the least data, with 74 responses, accounting for 13% of the total afternoon data. In the evening survey: Space B had the most data, with 53 responses, accounting for 45.6% of the total evening data. Spaces C and D had the least data, each with 14 responses, accounting for 12% of the total evening data. This phenomenon is determined by the needs of university students’ campus life and the dominant functions of the four different spaces. During the morning period, students concentrate their activities around class transitions at 8:00, 10:00, and 12:00. Therefore, Space D, adjacent to the teaching buildings (south side plaza of the main building), sees more student activity. In the afternoon, the pedestrian flow in the four typical spaces increased, with Space A showing the most significant change. In the afternoon, as the temperature rose and the solar angle increased, solar radiation intensified, and meteorological conditions improved. As a result, the number of people engaging in outdoor study and activities in Space A gradually increased. In the evening, as temperatures drop and metabolically active, exercising students have higher cooling needs, Space B sees a higher proportion of students compared to other spaces.

In terms of activity types, based on the statistics of the respondents’ activities during the first 20 min, we classified the primary behaviors in these four typical spaces into the following six categories: (1) Running or playing sports; (2) Fast walking or cycling; (3) Walking at a normal pace; (4) Standing while chatting or using a mobile phone; (5) Sitting while reading or using a mobile phone; (6) Sleeping or lying down.

Statistics and analyses were conducted separately for each of the four typical spaces, with the results displayed in Fig. 3.

Different activity states have significant impacts on thermal sensation and comfort30. We can classify all activity types into dynamic activities and static activities. Dynamic activities include running or playing sports, fast walking or cycling, and walking at a normal pace. Static activities include standing while chatting or using a mobile phone, sitting while reading or using a mobile phone, and sleeping or lying down. It is evident from the data that in the four typical campus spaces, Spaces B and D predominantly feature dynamic activities; Spaces A and C exhibit a more balanced mix of static and dynamic activities.

Outdoor thermal baseline

NPET and NPETR

Based on the statistical and calculation results, we will analyze whether there is a statistically significant correlation between PET and TSV. selecting all TSV vote results for every 1 °C of PET as a set and calculating the average TSV vote value (MTSV) for each group of data. The final results were processed and entered into SPASS for Spearman correlation analysis to determine the relationship between TSV votes and PET among university students. The results indicate a significant correlation between TSV and PET (Table 6).

The scatter plots of the MTSV vote values corresponding to each 1 °C PET increment was created (Fig. 4), We plotted the data points on a scatter plot and calculated the standard residuals to check if they follow a normal distribution (Table 7). The results showed that all p-values were greater than 0.05, indicating a normal distribution. Based on this, linear fitting was performed, and the resulting regression equation is as follows:

When MTSV = 0, the corresponding PET is the Neutral Physiological Equivalent Temperature (NPET). By substituting into the regression equations, the NPET values are calculated as follows: 14.3 °C for Space A; 9.5 °C for Space B; 15.3 °C for Space C; 11.8 °C for Space D; and an overall NPET of 13.9 °C. Notably, the NPET value in Space B (basketball court) is significantly lower than in other spaces, likely due to the respondents having recently engaged in high-intensity activities, resulting in a higher heat dissipation demand and a higher thermal sensation rating compared to other spaces. Space D shows the lowest regression slope (0.04907), indicating a relatively lower thermal sensitivity among its respondents, possibly because those surveyed in this space had higher clothing insulation and a generally higher satisfaction with the current thermal comfort, leading to a tendency towards “comfortable” thermal sensation ratings.

When 0.5 ≤ MTSV ≤ 0.5, the corresponding PET range is the Neutral Physiological Equivalent Temperature Range (NPETR). Substituting into the regression equations, the NPETR values are: 10.5 to 18.0 °C for Space A; 4.2 to 14.7 °C for Space B; 11.3 to 19.3 °C for Space C; 1.6 to 22.0 °C for Space D; the total voting results show the NPETR for university students in Xi’an to be 9.4 to 18.4 °C.

Preferred temperature

NPETR reflects the range of temperatures at which the human body feels most comfortable and natural in a specific environment. However, people’s subjective temperature preferences in a given environment do not fully coincide with NPET and are influenced by various factors, including individual physiological characteristics, psychological factors, lifestyle habits, and cultural differences. Each person’s temperature preferences may vary. In a questionnaire survey conducted among university students in a specific campus in Xi’an, we investigated environmental temperature preferences to further study the preferred temperatures of university students.

In the questionnaire, we collected respondents’ preferences for the current environmental temperature: preferences for increased temperature, no change, and decreased temperature. Based on the data collected, we researched the correlation between PET and thermal preferences: selecting all thermal preference results for every 1 °C increase in PET to form a set and calculating the percentage of votes preferring warmer and cooler temperatures within each set. The organized results were entered into SPASS for Spearman correlation analysis to determine the relationship between thermal preference expectations of university students and PET. The results showed a significant correlation between thermal preferences and PET, with a preference for warmer temperatures negatively correlated with PET, and a preference for cooler temperatures positively correlated with PET.

In our analysis, the preferences for “no change in temperature” within each data set were averaged and randomly assigned to the data for “prefer warmer” and “prefer cooler” temperatures. This division resulted in classifying all preferences within each 1 °C PET increment into two categories: “Hotter” and “Colder.” We then calculated the percentage of preferences for Hotter and Colder within each 1 °C PET. We conducted a normality test on the residuals of the scatter plot. Table 8 shows that the data residuals follow a normal distribution. Based on this, we performed function fitting, and the resulting regression equation is as follows:

By calculating the intersection of these regression fits, we identify the preferred temperature of university students in Xi’an (Cheung and Jim 2017). The intersection of the two regression lines, representing the balance point between preferences for warmer and cooler temperatures, occurs at a PET of 15.15 °C. This indicates that the preferred thermal temperature for university students in the Xi’an area is 15.15 °C, which is 1.25 °C higher than the NPET (13.9 °C). This finding suggests that university students in Xi’an prefer a warmer environmental temperature (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Met and TSV

To investigate the relationship between activity intensity and TSV, we performed a Spearman correlation test on the metabolic level of the subjects and TSV. The results showed R² = 0.110**, P = 0.001, indicating a statistically significant correlation. This suggests that activity intensity is positively correlated with TSV. We calculated the MTSV under various activity intensities, plotted scatter diagrams, and performed a linear fitting (Fig. 6). The regression equation is as follows:

\({\text{MTSV}}\,=\,0.{\text{2742MET}}\,+\,0.0{\text{1688 }}\left( {{{\text{R}}^{\text{2}}}\,=\,0.{\text{4421}}} \right)\)

Outdoor thermal baseline

NPET and NPETR

The overall NPET value for university students is calculated to be 13.9 °C, with variations among the four different spaces. Spaces A and C have similar NPET values, which are higher compared to those in Spaces B and D, with Space B having the lowest NPET value (Table 9). These differences are closely related to the characteristics of each space and the activities of the people within them. Space A, with dense tree shade and complex surrounding buildings, receives less solar radiation in the morning compared to the other three spaces, resulting in a slightly lower thermal environment assessment. Respondents in Space B, often engaged in high-intensity sports shortly before surveying, have a greater need for cooling, leading to a higher thermal sensation compared to respondents in other spaces. Space C, with extensive greenery and a pond, experiences heat absorption through water evaporation, and the high humidity intensifies the perception of temperature, making it feel cooler and leading to the highest NPET values among the areas surveyed. Space D, an open plaza with no shade, has the highest average air temperature among the spaces, at 22.7 °C, resulting in thermal evaluations just below those of Space B.

NPET and preferred temperature

Based on our analysis and calculation results, the preferred temperature for university students in Xi’an is 15.15 °C, which is 1.25 °C higher than the NPET (13.9 °C). The difference between the preferred temperature and NPET is related to various physiological, psychological, environmental, and individual factors. These differences arise from the complexity of human perception of temperature and thermal comfort. For example, some individuals have a natural preference for warmer environments and, even if the PET indicates that their current environmental conditions are already suitable, they tend to prefer higher temperatures.

Thermal sensitivity

In this study, an analysis was conducted on the meteorological parameters and questionnaire survey responses from university students in four distinct campus spaces in Xi’an. The regression fits between PET and MTSV showed varying slopes across the spaces: Space A had a regression slope of 0.1335; Space B, 0.09454; Space C, 0.1262; Space D, 0.04907; with an overall regression slope of 0.1114. Students in Spaces A and C exhibited higher thermal sensitivity, while those in Spaces B and D showed relatively lower thermal sensitivity. It is noted that Spaces B and D have higher proportions of dynamic activities, at 64% and 66% respectively, compared to 51% and 48% in Spaces A and C, respectively. The metabolic rates in these spaces also vary, with Space A averaging 1.6 met, Space B 1.9 met, Space C 1.5 met, and Space D 1.7 met. Higher metabolic rates tend to correlate with lower thermal sensitivity31.

Optimal design of open space

Through further analysis of the above research results, such as regional meteorological parameters, respondents’ preference voting, physical variables, etc., the physical, physiological and psychological factors affecting respondents’ thermal perception are obtained, and the four research areas are optimized to improve people’s thermal comfort. As shown in Table 10, various factors affecting people’s thermal perception in four typical Spaces are shown, and optimization strategies are proposed accordingly.

Conclusions and future prospects

Conclusions

Through in-depth research on the thermal perception characteristics in four typical open spaces within a university campus in Xi’an, significant conclusions were drawn from meteorological observations and questionnaire surveys, The main findings are as follows:

-

(1)

Globe temperature (Tg, r = 0.964**), wind speed (Va, r = 0.857*), air temperature (Ta, r = 0.821*), and solar radiation (G, r = 0.786*) are the primary factors affecting students’ thermal sensation in open campus spaces. Among the four measurement points, respondents showed clear preferences regarding humidity and solar radiation, with most preferring to maintain current temperature and wind speed. Respondents tend to improve their thermal sensation through changes in humidity and solar radiation.

-

(2)

In the university campuses in Xi’an, the NPET values for the four different typical open spaces are: Space A at 14.3 °C; Space B at 9.5 °C; Space C at 15.3 °C; and Space D at 11.8 °C; with an overall NPET value of 13.9 °C.

-

(3)

The NPETR values for the four different typical open spaces in Xi’an are: Space A at 10.5 to 18.0 °C; Space B at 4.2 to 14.7 °C; Space C at 11.3 to 19.3 °C; and Space D at 1.6 to 22.0 °C; with the overall voting results showing that the NPETR for university students in Xi’an is 9.4 to 18.4 °C.

-

(4)

The preferred temperature for university students in the Xi’an area is 15.15 °C, which is 1.25 °C higher than the NPET (13.9 °C). This indicates that university students in Xi’an prefer a warmer environmental temperature.

Limitations

Despite detailed meteorological measurements and questionnaire surveys conducted in open spaces within a university campus in Xi’an to explore students’ thermal perception and activity distribution in different typical spaces, this study still faces several limitations:

-

(1)

Sample Limitation: The sample mainly covered students from a specific university. The thermal perception of other age groups and social groups may be influenced by different psychological and physiological factors. Future research will aim to expand the sample size to include a more diverse population.

-

(2)

Geographical Limitation: The study was conducted at a university in Xi’an, and the heterogeneity in climate, geographical characteristics, and cultural backgrounds of different regions may cause regional biases in the results. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of thermal perception in open spaces, future studies could consider conducting comparative research in different geographical areas to gather more comprehensive and diverse information.

-

(3)

Seasonal Variation: The research was carried out over a specific time period without considering the potential impacts of seasonal changes on thermal perception. Different seasons could lead to variations in the results, hence future research should include observations across different seasons to capture more comprehensive data. Considering the effects of seasonal changes in temperature and humidity on human thermal perception could enhance the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the research.

-

(4)

Spatial Characteristics Limitation: While the study focused on four typical campus spaces, it did not explore in depth other factors that might influence crowd behavior and thermal perception, such as architectural structures and topography. Future research should take these factors into account more comprehensively to better understand the diversity of thermal perception in open spaces.

Future prospects

-

(1)

Comparative Studies Across Different Locations: Future studies could expand the geographical scope to include university campuses under different climatic and geographical conditions to better understand the characteristics of thermal perception in open spaces across different regions. Such comparative research would help identify how regional differences affect the use and thermal perception of open spaces.

-

(2)

Seasonal Studies: To more comprehensively understand the impact of seasonal changes on thermal perception in open spaces, future studies could conduct long-term observations across different seasons. This would provide more comprehensive data support for the design of campus open spaces, catering to seasonal needs.

Data availability

The datasets used or analysed during thecurrent study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Clo:

-

Clothing thermal resistance unit

- ISO:

-

International Organization for Standardization

- G:

-

Global Radiation

- MTSV:

-

Mean thermal sensation vote

- PMV:

-

Predict mean vote

- PET:

-

Physiological equivalent temperature

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

- SVF:

-

Sky view factor

- SET*:

-

Standard effective temperature

- TSV:

-

Thermal sensation vote

- TCV:

-

Thermal comfort vote

- Ta :

-

Air temperature

- Tg :

-

Globe temperature

- Tmrt :

-

Mean radiant temperature

- Va :

-

Wind speed

- NPET:

-

Neutral physiological equivalent temperature

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent

References

Li, Y. et al. Socioeconomic drivers of urban heat Island effect: Empirical evidence from major Chinese cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 63, 102425 (2020).

Meng, Q. et al. Characterizing spatial and temporal trends of surface urban heat island effect in an urban main built-up area: A 12-year case study in Beijing, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 204, 826–837 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Optimizing local climate zones to mitigate urban heat Island effect in human settlements. J. Clean. Prod. 275, 123767 (2020).

Yang, Q., Huang, X. & Tang, Q. The footprint of urban heat Island effect in 302 Chinese cities: Temporal trends and associated factors. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 652–662 (2019).

Pyrgou, A. & Santamouris, M. Increasing probability of heat-related mortality in a Mediterranean city due to urban warming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15 (8), 1571 (2018).

Marino, C., Nucara, A. & Pietrafesa, M. Thermal comfort in indoor environment: effect of the solar radiation on the radiant temperature asymmetry. Sol. Energy 144, 295–309 (2017).

Ji, Y., Song, J. & Shen, P. A review of studies and modelling of solar radiation on human thermal comfort in outdoor environment. Build. Environ. 214, 108891 (2022).

Lim, C. L. Fundamental concepts of human thermoregulation and adaptation to heat: a review in the context of global warming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(21), 7795 (2020).

Otani, H. et al. Exposure to high solar radiation reduces self-regulated exercise intensity in the heat outdoors. Physiol. Behav. 199, 191–199 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Effect of direct solar projected area factor on outdoor thermal comfort evaluation: A case study in Shanghai, China. Urban Clim. 41, 101033 (2022).

Tan, P. Y. et al. A method to partition the relative effects of evaporative cooling and shading on air temperature within vegetation canopy. J. Urban Ecol. 4(1), juy012 (2018).

Kotzen, B. An investigation of shade under six different tree species of the Negev desert towards their potential use for enhancing micro-climatic conditions in landscape architectural development. J. Arid Environ. 55 (2), 231–274 (2003).

Peker, E. Campus as an Integrated Learning Environment: Learning in Campus Open Spaces (Middle East Technical University, 2010).

Scholl, K. G. & Gulwadi, G. B. Recognizing campus landscapes as learning spaces. J. Learn. Spaces 4(1), 53–60 (2015).

Li, D. & Sullivan, W. C. Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landsc. Urban Plann. 148, 149–158 (2016).

Gilavand, A. The impact of educational furniture of schools on learning and academic achievement of students at elementary level. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 5(7S), 343–348 (2016).

Ahmadi Afusi, Z., Zarghami, Z. & Mahdinejad, J. A study on designing open space school and its relation. With improving happiness among students. Indian J. Fundamental Appl. Life Sci. 4(S3), 924–931 (2014).

Engemann, K. et al. Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116(11), 5188–5193 (2019).

Sun, Y., Luo, X. & Ming, H. Analyzing the time-varying thermal perception of students in classrooms and its influencing factors from a case study in Xi’an, China. Buildings 12(1), 75 (2022).

Lin, B. Research on the Impact of Greening on Outdoor Thermal Environment. Doctoral thesis, (Tsinghua University, Beijing, 2004).

Derimian, Y. et al. Importance of accounting for details in aerosol and underlying surface characteristics in calculations of shortwave aerosol radiative effect. in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts (2018).

Zhao, C. et al. A geographically weighted regression analysis of the underlying factors related to the surface urban heat Island phenomenon. Remote Sens. 10 (9), 1428 (2018).

Zhong, X. et al. Investigating the effects of surface moisture content on thermal infrared emissivity of urban underlying surfaces. Constr. Build. Mater. 327, 127023 (2022).

Jeon, J. Y. & Hong, J. Y. Classification of urban park soundscapes through perceptions of the acoustical environments. Landsc. Urban Plann. 141, 100–111 (2015).

Höppe, P. The physiological equivalent temperature–a universal index for the biometeorological assessment of the thermal environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 43(2), 71–75 (1999).

Cheung, P. K. & Jim, C. Y. Determination and application of outdoor thermal benchmarks. Build. Environ. 123, 333–350 (2017).

Fang, Z. et al. Investigation into sensitivities of factors in outdoor thermal comfort indices. Build. Environ. 128, 129–142 (2018).

Lai, D. et al. Studies of outdoor thermal comfort in Northern China. Build. Environ. 77, 110–118 (2014).

Matzarakis, A., Mayer, H. & Iziomon, M. G. Applications of a universal thermal index: Physiological equivalent temperature. Int. J. Biometeorol. 43(2), 76–84 (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. Experimental investigation into the effects of different metabolic rates of body movement on thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 168, 106489 (2020).

Hasan, M. H., Alsaleem, F. & Rafaie, M. Sensitivity study for the PMV thermal comfort model and the use of wearable devices biometric data for metabolic rate estimation. Build. Environ. 110, 173–183 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B. designed the experiment and modified the paper. Z.S. and K.M. wrote the paper. G.B. modified the English language. Z.S. and K.M. conducted the questionnaire survey. Y.Z. designed and directed the questionnaire experiment.There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, G., Sheng, Z., Min, K. et al. The study of outdoor thermal comfort in open spaces of cold climate campus. Sci Rep 15, 12756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97758-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97758-x