Abstract

Transforming growth factor-β superfamily genes are multifunctional cytokines that play central roles in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, adhesion, and migration. Identifying the TGF-β superfamily in crabs could provide a basis for elucidating the genetic regulatory mechanism of growth, development, sex differentiation and environmental adaptation. To understand the complexity and evolution of the TGF-β superfamily in the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis, this study comprehensively and systematically analysed this superfamily in the genome of E. sinensis. A total of 9 TGF-β superfamily genes have been identified, including EsBMP2, EsBMP3, EsBMP7, EsBMP10, EsBMP15, EsGDF8, EsUnivin, EsINHB and EsINHBB. A wide variation in the number of motifs and CDSs was found among different subfamilies. The expression of EsBMP2 and EsBMP7 suggested that these genes may be the main genes controlling embryonic development in E. sinensis. EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 are very highly expressed in the gills. The TGF-β superfamily genes presented different expression patterns during limb regeneration and molting. In addition, this gene family also responds to environmental stresses, including nanoplastic stress, cadmium stress, air exposure, and high-salinity stress, which provides a new perspective for understanding the strong tolerance and adaptability of crabs to environmental stress. To our knowledge, this study is the first genome-wide investigation of the TGF-β superfamily in crabs. This study identified the sequence structure, phylogenetic relationship, and gene expression profiles of the TGF-β superfamily genes in the Chinese mitten crab, and the above results lay a foundation for further investigation of the evolution and biological functions of this gene family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) is an economically cultured crustacean that belongs to the family Varunidae. It is native to the western Pacific coastal areas of China and Korea and has invaded North America and Europe1. It is warmly welcomed all over China for its unique flavour and rich nutritional value. Since the 1980s, with the advancement of aquaculture modernization and the increase in market demand, the aquaculture industry of Chinese mitten crab has developed rapidly2. The annual aquaculture production of E. sinensis reached 815,318 tons in 20223. However, the current culture industry of E. sinensis still faces many problems, such as sexual precocity, low growth rates and survival rates, and various diseases4. Therefore, investigating the genetic regulatory mechanism of growth, sex differentiation and environmental adaptation is important for crab breeding.

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily comprises ubiquitously expressed multifunctional cytokines that are distributed in vertebrates and invertebrates5. The TGF-β superfamily triggers cellular responses by forming a heteromeric complex with specific type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors6. The TGF-β superfamily regulates cell metabolism, growth, proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, migration, and apoptosis and is involved in many complex biological processes, such as embryonic development, neurogenesis, homeostasis, axis determination, muscle growth, and sex differentiation7. The proteins of the TGF-β superfamily are highly conserved in sequence and are marked by the existence of 6–9 cysteine residues, which participate in the formation of intramolecular disulfide bonds and are critical for the maintenance of protein structure and function5. The TGF-β superfamily comprises more than 30 members, which can be subclassified into several subfamilies, including the TGF-β isoforms, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), growth differentiation factors (GDFs), activins, inhibin (INH), nodal, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), and other subfamilies8,9. The TGF-β superfamily has been extensively studied in many species. The number of TGF-β superfamily members varies from a few to dozens in different species5. Previous studies revealed that BMP210,11, BMP712,13, BMP9/1014 and GDF15 exist in crabs, but identification of the TGF-β superfamily in the whole genome of any crab species has not yet been reported.

BMPs is a large subfamily and can be further divided into several subgroups, such as the BMP2/4 group, BMP5-8 group, BMP9/10 group, and BMP12-14 group. The BMP subfamily plays crucial roles in a variety of vital processes, such as cardiogenesis16, axial development17, eye development17, osteogenesis18,19,20, and sex determination/differentiation11,14,21. BMP2 is an important growth factor that plays a key role in multipotent stromal cells toward the osteogenic lineage for bone regeneration18. Loss of both BMP2 and BMP4 affects osteogenesis in mice22. Recent studies have shown that BMP2 in E. sinensis is highly expressed in the testis and participates in spermiogenesis10. BMP7 is closely related to the development of the dorsal-ventral pattern, eye, heart, and reproductive system16,17. BMP7 is also involved in testis development in E. sinensis13, and it potentially plays a role in early ovarian development in the mub crab (Scylla paramamosain)12. BMP9/10 in S. paramamosain might be involved in oocyte maturation by regulating cyclin abundance14. Previously, BMP2 and BMP7 were identified in E. sinensis; however, few studies have comprehensively analysed all the BMP subfamily members in crabs.

The GDF subfamily includes GDF3, GDF8, GDF11, GDF15 and other members, which is involved in the development of muscle, neuronal axons, and cartilage. For example, GDF8, also known as myostatin, plays a key role in muscle growth and development, and its loss of function in mice results in a large increase in skeletal muscle mass23. Studies have also shown that GDF8 inhibition enhances musculoskeletal recovery and chondrocyte proliferation, suggesting that GDF8 is a negative regulator of muscle growth24,25. In addition, other members of the TGF-β superfamily, such as Univin and INH, play unique roles in specific biological processes. Univin regulates dorsal-ventral axis formation and promotes skeletal growth in early embryos in the sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus)26,27, and Univin is highly expressed in eggs and prehatching blastula in the sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus)28 (Stenzel 1994). INH is a disulfide-linked heterodimer that contains an α-subunit and a βA or βB subunit to form INH A and INH B29. Activin is a dimer of the β-subunit, which is another member of the TGF-β superfamily29. Activin/INH has been suggested to play an important role in spermatogenesis and the regulation of oocyte maturation in vertebrates30,31.

In view of the importance of the TGF-β superfamily in various developmental and physiological processes, a systematic study of TGF-β superfamily genes in the Chinese mitten crab is necessary. To date, studies of the TGF-β superfamily in crabs have focused mainly on single genes, such as BMP2 and BMP7 in E. sinensis10,13. Systematic research on the TGF-β superfamily genes of the crab is lacking. Recently, completed genome sequencing of E. sinensis has laid the foundation for elucidation of the TGF-β superfamily at the genome-wide level32. Several questions that we want to answer in this study are as follows. How many types of the TGF-β superfamily are present in E. sinensis? Is there any difference in their expression among different tissues and different development stages? Is the expression of the TGF-β superfamily modulated in physiological processes and environmental stresses in crabs? In this study, homologous genes of the TGF-β superfamily in E. sinensis were identified, and gene characteristics, sequence structure, and phylogenetic relationships were analysed. Using transcriptome resources, the gene expression profiles of these genes at different developmental stages and in different tissues, as well as their expression patterns under various stress conditions, were investigated. The identification of the TGF-β superfamily is important for providing a basis for the study of its structural characteristics, evolutionary history, and functional mechanisms in crabs.

Materials and methods

Genome-wide identification of the TGF-β superfamily

To identify the TGF-β superfamily genes in the Chinese mitten crab, the genome and annotation files of E. sinensis (GenBank: GCA_024679095.1) were downloaded from the NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_024679095.1/). The BLAST and HMM programs were used to search for TGF-β superfamily candidate genes with a TGF domain query (accession: PF00019) (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk) (E value = 10−5). The SMART plugin in TBtools software (version 2.136) confirmed that each candidate member had a conserved domain in the TGF-β superfamily, and the number of amino acids (aa), molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity of the discovered proteins were predicted33.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TGF-β superfamily genes

A total of 182 TGF-β protein sequences were downloaded from the NCBI database from various species, such as Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, zebrafish (Danio rerio), Atlantic stingray (Hypanus sabinus), the swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus), the snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio), the black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon), the blacklip abalone (Haliotis rubra), the red abalone (H. rufescens), and some other species (Table S1). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the above 182 TGF-β protein sequences and proteins encoded by 9 TGF-β superfamily genes identified from E. sinensis. First, multiple sequence alignments were created via MAFFT v7.158b. Next, we constructed a phylogenetic tree via IQ-TREE v2.2.0 with the options -m MFP -bnni B 4000 -T AUTO. Finally, the phylogenetic tree was visualized via the iTOL (interactive tree of life) online tool (https://itol.embl.de/). The pairwise similarity of the identified TGF-β superfamily members in crabs was analysed via Protein pairwise similarity matrix in TBtools software (version 2.136).

Gene structure and protein domains

To explore the structure of the TGF-β superfamily, the MEME website (http://meme-suite.org/) was used to identify the conserved motifs of the TGF-β proteins. The parameters are as follows: the maximum length of conserved motifs is 50; the minimum length is 6; the maximum number of conserved motifs is 20; and the other parameters are the default values. The distributions of the UTRs and CDSs of these genes were analysed via TBtools software (version 2.136). In addition, the conserved domains of the TGF-β protein in E. sinensis were analysed via Batch SMART plugin in TBtools software (version 2.136). The generated conserved domain files were visualized via the iTOL online tool.

Expression profiles of TGF-β superfamily genes during development and in tissues

To investigate the expression patterns of the TGF-β superfamily genes in E. sinensis, we extracted publicly available transcriptome data from the NCBI SRA database (Table S2). The transcriptome data include gene expression profiles at different embryonic developmental stages (SRR3623083-SRR3623090), in different tissues (SRR10058623-SRR10058634 & SRR10276365-SRR10276369)1, during limb regeneration (SRR14684324-SRR14684347)32 and molting (SRR9179340-SRR9179351)34. The chemical-exposure stress experiment included 4 groups: control, nanoplastic exposure (1.0 × 1010 particles/L; Np), cadmium exposure (15 µg/L; Cd), Np-Cd exposure to 1.0 × 1010 particles/L Np and 15 µg/L Cd (SRR27675800-SRR27675803 & SRR27645890-SRR27645893)35. During the air exposure stress experiment, healthy crab individuals were cultured for 1, 3, or 5 days at 27◦C, 95% humidity, 14 h light, 10 h dark, and no water (SRR7507779-SRR7507782)36. During acute high salinity stress experiment, healthy crabs were challenged with 16‰, 28‰, or 35‰ saltwater, respectively (SRR6516036-SRR6516041)37. The raw RNA sequencing reads were trimmed using the NGStoolkit program with default parameters38. The clean reads were subsequently mapped to the reference genome using HISAT239. The resulting SAM files were then converted into BAM files and sorted using SAMtools40. The transcripts per million mapped reads (TPM) values for each gene were determined via StringTie v2.1.741. The TPM values > 30, ≤ 30, ≤ 20, ≤ 10, ≤ 5, ≤ 1, and 0 were classified as very high expression, high expression, moderately high expression, moderate expression, low expression, very low expression, and no expression, respectively. Heatmaps were drawn via TBtools software (version 2.136).

Validation of expression profiles by RT-qPCR

To validate the results of the transcriptome sequencing findings via RT-qPCR, we selected 4 genes: EsBMP2, EsBMP7, EsBMP10, and EsGDF8. Tissues, including the hepatopancreas, gill, muscle, and eyestalk, were collected from 9 healthy E. sinensis crabs, and three individuals were combined into one sample. Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were the same as those previously described by Zhang et al.42. All cDNA samples were synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA with PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Japan), and diluted by 30-fold in nuclease-free water. Gene-specific primers were designed with Primer 5.0, with the β-actin gene used as the reference gene (Table S3)43. The primer efficiency was between 90 and 110%. RT-qPCR was performed using the THUNDERBIRD® SYBR® qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Japan) on the CFX96-Real System (Bio-Rad, USA). The total volume of the reaction was 10 µL, containing 5 µL of qPCR mix, 1 µL of diluted cDNA, 0.3 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µmol/L), and 3.4 µL of DEPC-H2O. The program was as follows: 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, annealing temperature (Table S3) for 15 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a melting curve. For each cDNA sample, qPCR was performed in four technical replicates. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the relative expression levels, and the transcriptome data and the RT-qPCR results were compared44.

Results

Identification and characterization of TGF-β superfamily genes

In this study, a total of 9 TGF-β superfamily genes were identified in E. sinensis. The number of amino acids in the TGF-β proteins ranged from 338 to 510 (Table 1). The amino acid sequences are shown in Table S4. The molecular weight of the longest TGF-β protein is 57.08 kDa, and the molecular weight of the shortest TGF-β protein is 38.85 kDa. The theoretical isoelectric point is between 5.47 and 9.24. Notably, the minimum instability index of these identified proteins is 39.37, and most of the instability indices exceed 40. The aliphatic indices range from 70.67 to 85.29, and the grand average hydropathicity of all the TGF-β proteins is negative, indicating that they are all hydrophilic.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TGF-β superfamily genes

A total of 191 TGF-β superfamily proteins from E. sinensis and other species were used to construct a phylogenetic tree, as shown in Fig. 1. There is one member from E. sinensis in the BMP2/4, BMP3, BMP5-8, BMP10, BMP15, GDF8 and Univin groups. They were named EsBMP2, EsBMP3, EsBMP7, EsBMP10, EsBMP15, EsGDF8, and EsUnivin, respectively. The INHB group contained two E. sinensis members, EsINHB and EsINHBB. Phylogenetic analysis of each subfamily revealed that E. sinensis and other crab species, such as P. trituberculatus and C. opilio, first clustered into a small clade and then clustered with shrimp species to form a large clade. In addition, the amino acid sequences of the identified members among the crabs were highly conserved, ranging from 54.62 to 88.69% between homologous genes (Table S5).

Conserved motifs and gene structure of the TGF-β superfamily

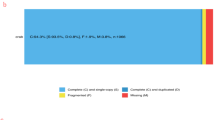

As shown in Fig. 2, a total of 20 conserved motifs, named motif 1-motif 20, were identified among the 9 TGF-β superfamily members. They are more conserved at the 3’-end, and all of them ended with motif 3 and motif 2. Motifs 1–4 belong to the TGF-β domain and contain 8 conserved cysteine residues (Table 2). The motifs in the TGF-β superfamily members vary greatly. For example, EsBMP7 and EsGDF8 contain 11 motifs, whereas EsBMP3 contains only 6 motifs. Genes from the same subfamily presented more similar conserved motifs. In addition, the number of CDSs varied greatly among the TGF-β superfamily in E. sinensis. EsBMP10 and EsBMP15 have 6 CDSs, EsBMP3, EsBMP7, and EsINHBB have 5 CDSs, and the other TGF-β superfamily members contain only 2–4 CDSs.

Figure 3 shows that all the TGF-β superfamily members of E. sinensis contain a TGF-β domain. Proteins encoded by seven of the identified genes (EsBMP2, EsBMP3, EsBMP7, EsGDF8, EsUnivin, EsINHB, EsINHBB) contain a signal peptide, and of 6 members (EsBMP2, EsBMP3, EsBMP7, EsBMP10, EsINHB, EsUnivin) have a Pfam: the TGF-β propeptide. Five members (EsBMP3, EsBMP7, EsBMP10, EsGDF8, EsUnivin) have a low-complexity region, whereas EsGDF8 and EsUnivin have two low-complexity regions. Only EsBMP15 has a transmembrane domain.

Spatiotemporal expression profiles of TGF-β superfamily genes

At different developmental stages, EsBMP2 was very highly expressed at the cleavage stage (4 d), and it was the only gene exhibiting a very high expression level during embryonic development (Fig. 4a). EsBMP2 decreased rapidly to moderately high expression at the blastula stage (12 d). EsUnivin was highly expressed at the heart beating stage (34 d). EsBMP7 was expressed from the blastula stage (12 d) to the hatched zoea stage (38 d), and its expression at the blastula (12 d), gastrula (23 d), eyed (33 d) and heart beating stages (34 d) reached moderately high levels. The EsBMP10 gene was expressed at moderate or low levels from the blastula stage (12 d) to the hatched zoea stage (38 d). In addition, EsBMP3, EsBMP15, EsGDF8, EsINHB, and EsINHBB were expressed at low level, very low level, or not expressed at embryonic developmental stages in E. sinensis.

The expression patterns of the TGF-β superfamily genes in different tissues are shown in Fig. 4b. In adult crabs, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were very highly expressed in the gills, which were significantly higher than those in other tissues. The expression profiles of EsBMP2 and EsBMP7 were consistent and were highly or moderately highly expressed in the abdomen and cephalothorax of megalopae and juveniles. In addition, EsGDF8 was moderately highly expressed in the abdomen of juveniles and muscle of adult crabs. In the gonads, only EsBMP7 was moderately highly expressed, while the expression levels of the other genes were lower. In eyestalks, EsBMP7 was highly expressed, whereas EsBMP2 was moderately highly expressed. In addition, all the TGF-β superfamily genes presented low, very low or no expression in the hepatopancreas. RT-qPCR was used to confirm the expression patterns of 4 genes, and the results were consistent with those of the transcriptome data (Fig. 5).

Expression profiles of TGF-β superfamily genes at different regeneration and molting stages

To determine the physiological roles of the TGF-β superfamily genes at different limb regeneration stages, we analysed the expression patterns of the TGF-β superfamily genes after amputation in muscle and eyestalk (Fig. 6). In muscle, the expression level of EsBMP2 was the highest at 15 d of limb regeneration, reaching moderately high expression, which was higher than that in the control group. EsINHBB was moderately expressed at 30 d of limb regeneration, which was also higher than that of the control group. In contrast, EsBMP7 was moderately highly expressed in the control group, whose expression was higher than its expression during limb regeneration. EsGDF8 was moderately expressed in the control group and expressed at lower levels after amputation. EsBMP3, EsBMP10, EsBMP15, EsUnivin and EsINHB were consistently stable at low or very low expression levels. In eyestalks, EsBMP7 was highly expressed in the control group and limb regeneration group (15 d), with no difference between these two groups. EsINHB was moderately highly expressed in the control group and decreased at 3 d and 15 d of limb regeneration. At 30 d, EsINHB returned to moderately high expression. The expression level of EsINHBB was moderately high at 30 d, which was higher than that in the control group. EsGDF8 was upregulated in eyestalk at 15 d and 30 d compared to the control group. EsBMP3, EsBMP10, EsBMP15, EsGDF8, and EsUnivin had low, very low or no expression in the eyestalks of the control and regeneration groups.

Figure 7 shows the expression profiles of the TGF-β superfamily genes at the different molting stages of E. sinensis. In gill, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were very highly expressed during the 4 different molting stages (Fig. 7a). However, the expression levels of these three genes fluctuated greatly during the molting cycle (Fig. 7b). Compared with those at the intermolt and premolt stages, the expression level of EsBMP2 increased several times at the ecdysis stage and decreased slightly at the postmolt stage. In contrast, the expression level of EsBMP7 slightly decreased at the ecdysis stage but significantly increased at the postmolt stage. EsBMP10 expression slowly increased throughout the molting cycle, and the expression level at the postmolt stage was approximately twice as high as that at the intermolt stage. EsINHBB was moderately expressed at the postmolt stage, which was higher than that at the other stages. The expression levels of the other 5 genes in the gills were low, very low, or not expressed and were not modulated by the molting process.

Expression profiles of TGF-β superfamily genes under different abiotic stresses

We analysed the gene expression profiles of the TGF-β superfamily genes in the gills and hepatopancreas of E. sinensis under Np exposure and Cd exposure (Fig. 8). In the gills, EsBMP2, EsBMP7, and EsBMP10 were very highly expressed; however, the differences were significant between the control group and treatment group. The transcription levels of EsBMP2 in the Np, Cd, and Np-Cd groups were all higher than those in the control group. The gene expression level of EsBMP7 increased under Np stress and significantly decreased under Cd exposure and Np-Cd treatment. The expression level of EsBMP7 in the Np-Cd group was much lower than that in the Np group or the Cd group. The transcription levels of EsBMP10 were reduced under all three stress conditions, and the gene expression in the Np-Cd group was less than half that in the control group. The other TGF-β superfamily genes in the gills were expressed at low levels, and the responses to Np and Cd exposure were not obvious. EsGDF8 and EsINHB were downregulated in NP, Cd and Np-Cd groups compared to the control group. The expression levels of the TGF-β superfamily genes in the hepatopancreas of E. sinensis were low among all the groups.

Under air exposure stress, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were also very highly expressed in the gills (Fig. 9). The expression of EsBMP7 was downregulated after 1 day of air exposure and upregulated consistently after 3 days and 5 days of air exposure. EsINHB and EsINHBB were upregulated during air exposure compared to the control group. The other TGF-β superfamily genes were expressed stably during adaptation to air exposure stress. In acute high-salinity stress, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were very highly expressed in haemocytes (Fig. 10). After challenge for 24 h, the expression of EsBMP2 and EsBMP10 at a salinity of 35 ppt was twice as high as that in the other low-salinity groups. EsBMP15 and EsINHBB were upregulated at 48 h and 24 h, respectively. Moreover, after exposure for 12 h, 24 h and 48 h at a salinity of 16 ppt, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were downregulated at 24 h, and their expression at 48 h gradually recovered to the same level as that at 12 h.

Discussion

We identified 9 TGF-β superfamily gene members in E. sinensis, and the number of this gene family differed little among invertebrates5. For example, there are 7, 8 and 10 TGF-β superfamily members in Drosophila5, oyster5, and the Pacific abalone H. discus hannai42, respectively. In invertebrates, the number of TGF-β superfamily genes is significantly lower than that in vertebrates5. For example, a total of 33 TGF-β superfamily members have been identified in humans, including 10 BMP members, 10 GDF members and 13 other members45. There are 30 and 48 TGF-β genes in blue whale46 and tilapia5, respectively. The expansion of the TGF-β superfamily in vertebrates is likely due to genome duplication events, which lay the foundation for the evolution of important functions, such as the more complex brain and heart5.

The life cycle of E. sinensis can be divided into several stages: the zoeal stage, the megalopa stage, the juvenile crab, and the adult crab47. In this study, EsBMP2 was very highly expressed in the cleavage stage (4 d), and EsBMP7 was continuously expressed from the blastocyst (12 d) to the heartbeat stage (34 d). These expression profiles of the TGF-β superfamily in E. sinensis are similar to those in other species. BMP2 and BMP7 are highly expressed during early embryo development in bovines48, chicken49, sea urchins50, and sponge51. These results illustrate that BMPs play key roles in early embryonic development, including gastrulation, mesoderm induction and axial patterning in the embryo. These findings suggest that EsBMP2 and EsBMP7 may be the main genes controlling embryo early development in crabs.

In adult E. sinensis, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were very highly expressed in the gills and expressed at low levels in the hepatopancreas, which was consistent with previous studies. The relative transcription level of BMP2 was highest in the gills and very low in the hepatopancreas in both E. sinensis10 and S. paramamosain11. Previous studies have revealed that BMP2 is highly expressed in male gonads in E. sinensis10 but is highly expressed in the ovaries of S. paramamosain11. However, in our study, EsBMP2 was expressed at very low level in the gonads. This difference may be due to the different gonadal development periods of the crabs collected. BMP7 has a potential role in testis development in E. sinensis, indicating that BMP7 can regulate the proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia13 and that BMP7 affects oocyte maturation in S. paramamosain52. In the present study, EsBMP7 was the most highly expressed gene in the gonads, which supports the important role of BMP7 in gonad development and reproductive processes. In addition, both EsBMP2 and EsBMP7 are generally highly expressed in the cephalothorax and abdomen of megalopa and juvenile crabs. The most obvious morphological feature that changes from megalopa to juvenile crab is brachyurization, which is a degenerated abdomen with entire folds beneath the thorax53. The universal expression pattern suggested that BMP2 and BMP7 may play multiple roles in brachyurization. EsGDF8 is moderately highly expressed in the abdomen and muscle, which is similar to previous findings54. The expression of a myostatin-like gene found in the blackback land crab was restricted to skeletal muscle15, suggesting that GDF8 participates in muscle growth regulatory mechanisms in crabs. The inhibition of GDF8 has the potential to enhance the combination of hyperplasia and hypertrophy of myosin heavy chain II striated myofibers in striated muscle, which could lead to an increase in muscle cellularity55.

The expression pattern of EsBMP2 in muscle during limb regeneration was consistent with that in crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus)56. BMP2 in crayfish continually increases in expression at the emergence of the unsegmented papilla period and then decreases at the late stage of limb regeneration56. The expression of EsGDF8 in muscle decreased after amputation (3 d, 15 d, and 30 d). Our results support the negative regulatory role of myostatin55. Therefore, EsBMP2 and EsGDF8 may be involved in limb regeneration in crabs. Regarding the molting, EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 were very highly expressed in the gills of E. sinensis, and their expression levels at the postmolt stage were higher than those at the intermolt stage. The activation of the TGF-β signalling pathway is critical for the maturation of molting glands and the production of ecdysones in the crab G. lateralis57. In Macrobrachium nipponense, the TGF-β signalling pathway performs an important function during molting by regulating the synthesis of ecdysone58. In bivalves, BMPs such as BMP2, BMP7, and BMP10 are key players in shell damage repair and calcification59. The BMP signalling pathway regulates the process of exoskeleton hardening during the molting process in S. paramamosain, and BMP2 in the hepatopancreas exhibits cyclic expression patterns during the molting phase60. TGF-β receptors have been reported to be involved in molting-related muscle growth in E. sinensis61,62,63; however, studies of the TGF-β superfamily involved in molting are rare. In addition, few studies have investigated the effects of BMP7 and BMP10 on the molting process in crustaceans60. In this study, our results revealed that BMP2, BMP7, and BMP10 may be involved in molting in crabs.

The TGF-β signalling pathway participates in the response mechanism under environmental stresses. The expression levels of the EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 genes in the gills changed greatly under Cd or Np stress. Heavy metals such as Cd can directly affect the TGF-β signalling pathway by binding to and altering the structure of the TGF-β receptor, which promotes the phosphorylation process of the receptor64, and this mechanism has also been observed in mammals65. In arthropods, members of the TGF-β signalling pathway were found to be cadmium-responsive transcription factors in the wolf spider Pardosa pseudoannulata66. The hepatopancreas of the Chinese mitten crab experiences oxidative damage due to exposure to Np conditions, with a decrease in the relative mRNA level of the TGF-β receptor gene67. Studies on the role of BMPs in the regulation of Np stress and heavy metals in invertebrates are rare. In addition, the results indicated that the expression profiles of EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 changed in response to air exposure stress and acute high salinity. E. sinensis is an economical crustacean with strong tolerance to environmental stress. Few studies have reported the response of the TGF-β superfamily to air exposure or high salinity. The very high expression of the EsBMP2, EsBMP7 and EsBMP10 genes may reflect an adaptive response mechanism of the crabs to environmental stress.

In summary, a total of 9 TGF-β superfamily genes (EsBMP2, EsBMP3, EsBMP7, EsBMP10, EsBMP15, EsGDF8, EsUnivin, EsINHB and EsINHBB) were identified in E. sinensis. The identified members of the TGF-β superfamily were evolutionarily conserved. This study provides not only a comprehensive understanding of the gene characteristics, sequence structure, and phylogenetic relationships but also insights into the growth, development, specific physiological processes, and adaptive regulatory mechanisms of this gene family in E. sinensis. In-depth studies will help us better understand how crabs respond and adapt to abiotic stress. Moreover, these results provide a more comprehensive understanding of the evolution and biological functions of the TGF-β superfamily genes in crabs.

Data availability

The Data can be requested upon the Corresponding Author.

References

Cui, Z. X. et al. The Chinese mitten crab genome provides insights into adaptive plasticity and developmental regulation. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22604-3 (2021).

Yang, F. et al. Comparison of. methodological proposal in sensory evaluation for Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) by data mining and sensory panel. Food Chem. 356, 129698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129698 (2021).

Yang, M. et al. The effects of dietary L-theanine on the growth performance, non-specific immunity, antioxidant status, and intestinal microflora of female Chinese mitten crabs (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquacult. Rep. 34, 101923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.101923 (2024).

Qiu, G. F. et al. A second generation SNP and SSR integrated linkage map and QTL mapping for the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Sci. Rep. 7, 39826. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39826 (2017).

Zheng, S. Q., Long, J., Liu, Z. L., Tao, W. J. & Wang, D. S. Identification and evolution. Of TGF-beta signaling pathway members in twenty-four animal species and expression in tilapia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041154 (2018).

Tzavlaki, K. & Moustakas, A. TGF-beta signaling. Biomolecules 10, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10030487 (2020).

Heldin, C. H. & Moustakas, A. Role of Smads in TGF-beta signaling. Cell. Tissue Res. 347, 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-011-1190-x (2012).

Weiss, A. & Attisano, L. The TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathway. WIREs Dev. Biol. 2, 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/wdev.86 (2013).

Hinck, A. P., Mueller, T. D. & Springer, T. A. Structural biology and evolution of the TGF-beta family. CSH Perspect. Biol. 8, a022103. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a022103 (2016).

Yang, T., Wei, B. H., Hao, S. L., Wei, Y. L. & Yang, W. X. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) mediates spermatogenesis in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis by regulating Kinesin motor KIFC1 expression. Gene 754, 144848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2020.144848 (2020).

Yang, Y. A., Zhang, P., Cui, Z. X. & Bao, C. C. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 is involved in oocyte maturation through an autocrine/paracrine pathway in Scylla paramamosain. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 748928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.748928 (2021).

Shu, L., Yang, Y. A., Huang, H. Y. & Ye, H. H. A bone morphogenetic protein ligand and receptors in mud crab: A potential role in the ovarian development. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 434, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2016.06.023 (2016).

Xu, Y. R., Wang, G. Y., Zhou, Y. C. & Yang, W. X. The characterization and potential roles of bone morphogenetic protein 7 during spermatogenesis in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Gene 673, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.020 (2018).

Yang, Y. A. et al. Identification of differentially abundant mRNA transcripts and autocrine/paracrine factors in oocytes and follicle cells of mud crabs. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 230, 106784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2021.106784 (2021).

Covi, J. A., Kim, H. W. & Mykles, D. L. Expression of alternatively spliced transcripts for a myostatin-like protein in the Blackback land crab, Gecarcinus lateralis. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 150, 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.04.608 (2008).

Bongiovanni, C. et al. BMP7 promotes cardiomyocyte regeneration in zebrafish and adult mice. Cell Rep. 43, 114162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114162 (2024).

Dong, X. R. et al. Functional differentiation of BMP7 genes in zebrafish: bmp7a for dorsal-ventral pattern and bmp7b for melanin synthesis and eye development. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 838721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.838721 (2022).

Wegman, F., Helm, Y. V. D., Öner, F. C., Dhert, W. J. A. & Alblas, J. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 plasmid DNA as a substitute for bone morphogenetic protein-2 protein in bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 19, 2686–2692. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0569 (2013).

Lowery, J. W. & Rosen, V. The BMP pathway and its inhibitors in the skeleton. Physiol. Rev. 98, 2431–2452. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00028.2017 (2018).

Halloran, D., Durbano, H. W. & Nohe, A. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 in development and bone homeostasis. J. Dev. Biol. 8, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdb8030019 (2020).

Lochab, A. K. & Extavour, C. G. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in animal reproductive system development and function. Dev. Biol. 427, 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.03.002 (2017).

Bandyopadhyay, A. et al. Genetic analysis of the roles of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 in limb patterning and skeletogenesis. Plos Genet. 2, e216. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0020216 (2006).

McPherron, A. C., Lawler, A. M. & Lee, S. J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 387, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/387083a0 (1997).

Elkasrawy, M., Fulzele, S., Bowser, M., Wenger, K. & Hamrick, M. Myostatin (GDF-8) inhibits chondrogenesis and chondrocyte proliferation in vitro by suppressing Sox-9 expression. Growth Factors 29, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.3109/08977194.2011.599324 (2011).

Brightwell, C. R. et al. GDF8 Inhibition enhances musculoskeletal recovery and mitigates posttraumatic osteoarthritis following joint injury. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi9134. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adi9134 (2023).

Zito, F. et al. Expression of univin, a TGF-beta growth factor, requires ectoderm-ECM interaction and promotes skeletal growth in the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Biol. 264, 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.07.015 (2003).

Range, R. et al. Cis-regulatory analysis of nodal and maternal control of dorsal-ventral axis formation by univin, a TGF-beta related to Vg1. Development 134, 3649–3664. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.007799 (2007).

Stenzel, P., Angerer, L. M., Smith, B. J., Angerer, R. C. & Vale, W. W. The univin gene encodes a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily with restricted expression in the sea urchin embryo. Dev. Biol. 166, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.1994.1303 (1994).

Kretser, D. M. D. & Robertson, D. M. The isolation and physiology of inhibin and related proteins. Biol. Reprod. 40, 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod40.1.33 (1989).

Makanji, Y., Temple-Smith, P. D., Walton, K. L., Harrison, C. A. & Robertson, D. M. Inhibin B is a more potent suppressor of rat follicle-stimulating hormone release than inhibin A in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology 150, 4784–4793. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2008-1783 (2009).

Cai, K. L. et al. Action mechanism of inhibin α-subunit on the development of Sertoli cells and first wave of spermatogenesis in mice. Plos One. 7, e25585. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025585 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Omics data unveil early molecular response underlying limb regeneration in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl4642. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abl4642 (2022).

Chen, C. J. et al. TBtools-II: A one for all, all for one bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant. 16, 1733–1742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010 (2023).

Li, J., Sun, J., Dong, X., Geng, X. & Qiu, G. Transcriptomic analysis of gills provides insights into the molecular basis of molting in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). PeerJ 7, e7182. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7182 (2019).

Che, S. et al. Toxic effects of nanopolystyrene and cadmium on the intestinal tract of the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Ecotox Environ. Safe. 270, 115936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.115936 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Gene expression profiles of gill provide insights into the aerial respiration capacity of the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Aquaculture 506, 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.03.027 (2019).

Xu, Y., Zheng, J., Yang, Y. & Cui, Z. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of DDE_Tnp_4 family genes in Eriocheir sinensis. Antibiotics 10, 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121430 (2021).

Patel, R. K. & & Mukesh, J. NGS QC toolkit: A toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS One 7, e30619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 (2012).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2578–2579. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Zhang, Q., Huang, J. F., Fu, Y. T., Chen, J. M. & Wang, W. Genome-wide identification and expression profiles of sex-related gene families in the Pacific abalone Haliotis discus Hannai. Comp. Biochem. Phys. D 50, 101205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbd.2024.101205 (2024).

Mo, N., Zhu, D. D., Liu, J. X., Feng, T. Y. & Cui, Z. X. Metabolic responses to air-exposure stress of the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) revealed by a combined analysis of metabolome and transcriptome. Aquaculture 548, 737710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737710 (2022).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Morikawa, M., Derynck, R. & Miyazono, K. TGF-beta and the TGF-beta family: Context-dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. CSH Perspect. Biol. 8, a021873. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021873 (2016).

Faiz, Z. et al. Comparative genomic studies on the TGF-beta superfamily in blue Whale. Mamm. Genome 35, 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-024-10031-w (2024).

Chen, S. S. et al. The identification, adaptive evolutionary analyses and mRNA expression levels of homeobox (hox) genes in the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. BMC Genom. 24, 436. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09489-w (2023).

Lee, K. B., Folger, J. K., Rajput, S. K. & Smith, G. W. Temporal regulation of mRNAs for select bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP), BMP receptors and their associated SMAD proteins during bovine early embryonic development: Effects of exogenous BMP2 on embryo developmental progression. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 12, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-12-67 (2014).

Chapman, S. C., Schubert, F. R., Schoenwolf, G. C. & Lumsden, A. Analysis of Spatial and Temporal gene expression patterns in blastula and gastrula stage chick embryos. Dev. Biol. 245, 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2002.0641 (2002).

Donoughe, S., Ewen-Campen, N. T., Green, D. A., Henderson, L., Extavour, C. G. & B. &,, BMP signaling is required for the generation of primordial germ cells in an insect. PNAS 111, 4133–4138. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1400525111 (2014).

Adamska, M. et al. Wnt and TGF-beta expression in the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica and the origin of metazoan embryonic patterning. Plos One 2, e1031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001031 (2007).

Yang, Y. N., Shu, L., Jiang, Q. L., Huang, H. Y. & Ye, H. H. Does the bone morphogenetic protein 7 inhibit oocyte maturation by autocrine/paracrine in mud crab? Gen. Comp. Endocr. 266, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.05.004 (2018).

Song, C. W. et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis provides insights into the molecular basis of brachyurization and adaptation to benthic lifestyle in Eriocheir sinensis. Gene 558, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.048 (2015).

Kim, K. S., Jeon, J. M. & Kim, H. W. A myostain-like gene expressed highly in the muscle tissue of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 12, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.5657/fas.2009.12.3.185 (2009).

Sun, X. J. et al. Molecular characterization of the myostatin gene and its regulation on muscle growth in yesso scallop Patinopecten yessoensis. Aquaculture 520, 734982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.734982 (2020).

Musgrove, L. et al. Transcriptomic analysis across crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus) claw regeneration reveals potential stem cell sources for cultivated crustacean meat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 8623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25168623 (2024).

Abuhagr, A. M. et al. Roles of mechanistic target of Rapamycin and transforming growth factor-beta signaling in the molting gland (Y-organ) of the Blackback land crab, Gecarcinus lateralis. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 198, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.03.018 (2016).

Yuan, H. W. et al. Deciphering molecular mechanisms governing the reproductive molt of Macrobrachium nipponense: A transcriptome analysis of ovaries across various molting stages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 11056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241311056 (2023).

Kin, K., Kakoi, S. & Wada, H. A novel role for Dpp in the shaping of bivalve shells revealed in a conserved molluscan developmental program. Dev. Biol. 329, 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.021 (2009).

Zhong, B. T. et al. Functional study on the BMP signaling pathway in the molting of Scylla paramamosain. Fishes 9, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes9070263 (2024).

Tian, Z. H., Peng, H. Y., Deng, W. D. & Jiao, C. Z. Identification of a transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor transcript in Eriocheir sinensis and its molting-related expression in muscle tissues. Mol. Biol. Rep. 47, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-019-05108-8 (2020).

Wang, J. A. et al. Molecular characteristic of activin receptor IIB and its functions in growth and nutrient regulation in Eriocheir sinensis. PeerJ 8, e9673. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9673 (2020).

Wang, M. Y. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis on the regulatory mechanism of thoracic ganglia in Eriocheir sinensis at post-molt and inter-molt stages. Life 12, 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12081181 (2022).

Bhat, A. A. et al. Pollutants to pathogens: The role of heavy metals in modulating TGF-beta signaling and lung cancer risk. Pathol. Res. Pract. 256, 155260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2024.155260 (2024).

Zhao, X., Wang, S. C., Li, X. J., Liu, H. G. & Xu, S. W. Cadmium exposure induces TNF-α-mediated necroptosis via FPR2/TGF-β/NF-κB pathway in swine myocardium. Toxicology 453, 152733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2021.152733 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Characterization of cadmium-responsive transcription factors in Wolf spider Pardosa pseudoannulata. Chemosphere 268, 129239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129239 (2021).

Huang, M. T. et al. Nanopolystyrene and Phoxim pollution: A threat to hepatopancreas toxicity in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquat. Toxicol. 276, 107124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2024.107124 (2024).

Funding

This work is supported by the Fuzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (2022-P-002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202991), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (No. 22ZR1426500), and the Minjiang University Talent Introduction Technology Project (MJY21008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. wrote the original draft. S.M and Y.S. collected and analyzed the data. H.Z. prepared the experimental materials. Q.Z. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, Y., Mou, S., Song, Y. et al. Genome-wide identification of the TGF-β superfamily and their expression in the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Sci Rep 15, 12709 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97772-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97772-z