Abstract

Cancer is a state of immunological imbalance associated with chronic inflammation and local immunosuppression. Introducing immune checkpoint inhibitors was a breakthrough in cancer treatment. However, the treatment outcomes remain unsatisfactory, and many patients still progress after the initial response. The study aimed to assess whether serum neopterin (NEO), an indicator of cellular immune activation, could be used as a predictor of the long-term benefits of drugs blocking the programmed cell death protein 1 pathway (anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs). We enrolled 103 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1s. Serum was collected at baseline and at the end of each treatment cycle for the first three months of immunotherapy. NEO concentrations were determined with a validated high-performance liquid chromatography assay and correlated with treatment outcomes. Low-NEO status (i.e., serum NEO levels ≤ 71.65 nM at the end of the 3rd treatment cycle and ≤ 66.84 nM at the end of the 4th treatment cycle) increased the odds of ≥ 12-month benefits (odds ratio, OR = 11.70, p < 0.001), and decreased the hazard of NSCLC progression (hazard ratio, HR = 0.327, p < 0.001) and treatment failure (adjusted HR = 0.450, p < 0.05). Patients with low-NEO status had three times longer progression-free survival (PFS, 17.3 vs. 5.9 months) and three times longer time to treatment failure (TTF, 16.3 vs. 5.5 months) compared to other patients. Baseline NEO levels could not discriminate between patients who had and lacked the long-term benefits of treatment. In conclusion, the on-treatment serum NEO concentrations could be a biomarker of the long-term benefits of the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment in advanced NSCLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a state of immunological imbalance associated with chronic inflammation and local immunosuppression.1 This observation was the basis for introducing a new group of cancer drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). The tumor develops diverse mechanisms to escape from the host immunosurveillance, including induction of dysfunctional T-cell signaling, production of a local immunosuppressive environment, and upregulation of negative immune checkpoints.2,3 Developing monoclonal antibodies directed against those immune checkpoints was a breakthrough in cancer treatment. For example, for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the 5-year overall survival (OS) exceeded 15% compared to the historical data, i.e., 5.5%.4

In NSCLC, the ICIs primarily target the programmed cell death protein 1 and its ligand 1 pathway (PD-1/PD-L1), i.e., molecules involved mostly in inhibiting the T-cell effector phase.5 Despite improved treatment outcomes, most NSCLC patients quickly progress after the initial response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1s,6 so the focus is on finding early biomarkers that could indicate patients who would benefit from immunotherapy in the long term. Special attention has been paid to blood-based biomarkers because blood, as a matrix, is easy and relatively non-invasive to collect. So far, the circulating immune cells, various cytokines, and soluble molecules have been explored, among others, as potential biomarkers for successful ICI treatment.7,8,9,10

A growing body of evidence indicates that poor response to immunotherapy may be associated with systemic inflammation. Accordingly, worse outcomes have been observed in patients with an unfavorable NLR (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio),11 a high SIRI (systemic inflammation response index),12 and high (or increasing) levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 or interleukin-8.7 An essential role in inflammation also play macrophages, the monocyte-derived immune cells, localized in every body tissue and classified as a part of the innate response.13 In cancer, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have been identified apart from tissue-localized macrophages, and they are the most abundant immune cells in the tumor environment.14

Macrophages have a dual role in cancer: on the one hand, they are responsible for the antitumor response; on the other, they contribute to cancer progression by promoting tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and local immunosuppression.14,15 These contrasting functions can be observed due to different polarization of TAMs, which results in the formation of pro-inflammatory macrophages M1 (classically activated) or anti-inflammatory M2 (alternatively activated). While M1 macrophages promote Th1 responses and have a tumoricidal effect, M2 macrophages are involved in Th2-driven response and tumor progression.16 The density of both M1 and M2 correlate with NSCLC prognosis. However, the effect largely depends on the macrophage localization: high M1 infiltration of the tumor islet has been linked with longer survival, while a high density of M2 in the tumor stroma—with shorter survival .17

As macrophages are metabolically active, they can be monitored not only by assessing the phenotypes of the cells but also by studying the products of their metabolism.15 The best-known metabolic pathway associated with macrophage activation involves the production of neopterin (NEO), a small 253 Da pteridine derived from guanosine triphosphate.18 NEO is almost exclusively produced by monocytes and macrophages upon stimulation with interferon-gamma (INF-γ),15 released from the activated T helper cells and natural killer cells.19 Therefore, high NEO concentrations are widely recognized as an indicator of cellular immune activation.15,18

In lung cancer, serum NEO levels are higher than in healthy people,20,21,22,23,24 but their prognostic value remains unclear. High serum NEO was linked with worse survival23 but not progression-free survival (PFS).25 Recently, NEO drove attention as a potential biomarker of response to ICIs. So far, only limited data are available, but the results are promising: high blood NEO was associated with worse outcomes in NSCLC and other tumors.25,26,27

For example, high serum NEO at baseline (n = 16) and after two months from the start of anti-PD-1 (n = 42) or anti-PD-L1 therapy (n = 3) was associated with shorter PFS in NSCLC.25 In another cohort (n = 53), lower plasma NEO before the PD-1 blockade correlated with better survival.26 High serum NEO before27 or during the anti-PD-1 treatment25 also characterized early progressors in melanoma (n = 29) and renal cell carcinoma (n = 79). However, these results should be treated with caution as they were not confirmed in the survival analysis.25,27

The study aimed to comprehensively assess whether serum NEO can be used as a biomarker of the long-term benefits of anti-PD-1/PD-L1s in NSCLC. Compared to previous studies,25,26 we included not only patients dosed with anti-PD-1 antibodies but also a large cohort of patients treated with the anti-PD-L1 drug. Moreover, we collected samples at baseline and at the end of four consecutive immunotherapy cycles. This dense sampling enabled, for the first time, the thorough monitoring of the kinetic changes in NEO levels throughout the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy to investigate the role of sampling time on the NEO concentrations.

Materials and methods

Study population and sample collection

This prospective, observational study was conducted at Wielkopolska Center of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery and University Clinical Hospital. Both centers were localized in Poznań, Poland. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Bioethics Committee at Poznan University of Medical Sciences (decision No. 80/19 and 562/22). All patients provided written informed consent. Participation in the study had no impact on the medical decisions and patients’ care.

We included patients with locally advanced (stage IIIB) and advanced (stage IV) NSCLC who were scheduled for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in the national NSCLC drug program. Based on the program’s criteria, patients received pembrolizumab (PEMBRO; first-line, 200 mg Q3W) or atezolizumab (ATEZO; first- or second-line, 1200 mg Q3W), depending on PD-L1 status and previous treatment.

Patients treated with immunotherapy as first-line (PEMBRO or ATEZO) were dosed in monotherapy if the expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissue was high (≥ 50%). In the case of low PD-L1 status, patients were scheduled for combined chemoimmunotherapy (PEMBRO in combination with pemetrexed and carboplatin or pemetrexed and cisplatin for non-squamous NSCLC; PEMBRO in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin for squamous and not otherwise specified NSCLC). Immunotherapy as second-line (ATEZO) was administered regardless of PD-L1 status. The absence of mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor gene (EGFR) and no rearrangement of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene (ALK) were confirmed for all patients with non-squamous NSCLC.

The treatment efficacy was assessed according to RECIST 1.1 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, v.1.1)28 and was classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD). The first on-treatment radiological response was evaluated about 2–3 months after immunotherapy initiation and then every three months. Immunotherapy could be discontinued due to confirmed progression, unacceptable toxicity, deteriorating and unacceptable quality of life, or death. All patients were followed up for survival until February 15, 2025.

Peripheral blood for biomarker assays was collected at baseline (before introducing immunotherapy) and at the end of cycles 1–4 (pre-dose). After centrifugation (1700×g for 15 min), serum was kept at –80 °C in aliquots. Samples were collected between February 2019 and August 2023, except for months between June 2020 and January 2022. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak (coronavirus disease 2019) and hospital restrictions, patients’ enrollment and sample collection at this interval were suspended.

Definitions

Smoking status was evaluated based on a questionnaire completed by each participant at the time of enrollment. Following the CDC guidelines29 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), smokers were defined as participants who smoked ≥ 100 cigarettes and either continued or quit smoking at enrollment (for current and former smokers, respectively). Never smokers were defined as participants who never smoked or smoked < 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height reported or measured at the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 initiation.

The survival data were calculated from the day of immunotherapy initiation to death (OS), confirmed progression or death (PFS), or treatment discontinuation for any reason (time to treatment failure, TTF). Patients who stopped the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment without progression but who died within the next three months were not censored in Kaplan–Meier analyses for PFS.

The long-term responders were defined as patients with disease control (CR, PR, and SD) whose clinical benefits lasted at least 12 months from the start of treatment. No benefits of treatment were defined as PD as the best response or no treatment evaluation due to earlier death or treatment discontinuation. Objective response was defined as at least PR.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was a percentage of long-term responders. The secondary endpoints were PFS, TTF, and OS.

Measurement of serum neopterin levels

Chemicals

D-( +)-neopterin (NEO, ≥ 97.5%), 3-nitro-L-tyrosine (3-NT, ≥ 98%), and trichloroacetic acid (TCA, ≥ 99%) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Formic acid (99%, LC/MS grade) was purchased from Carlo Erba Reagents (Val-de-Reuil, France). Bovine serum albumin (BSA, 99%) was obtained from Pol-Aura (Morąg, Poland), while phosphate buffer saline (PBS) pH 7.4—from Chempur (Piekary Śląskie, Poland). Solvents for chromatography (at least HPLC grade) were provided by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

HPLC-FLD/UV method

Serum NEO concentrations were determined by a validated high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method. The analyses were performed with the HP 1100 HPLC system (Hewlett Packard, Vienna, Austria), controlled by the ChemStation software. A Synergi Polar-RP 80Å column (100 × 2 mm, 4 μm), coupled with a corresponding guard column (both from Phenomenex, Torrance, USA), was used for separation, and 3-NT served as an internal standard (IS). NEO was detected with a fluorescence detector (FLD, with the excitation and emission wavelengths of 353 and 438 nm, respectively), while 3-NT—with an ultraviolet detector (UV, at λ = 275 nm). The aqueous mobile phase consisted of water with 0.1% formic acid, while the organic mobile phase—acetonitrile (ACN). The following gradient profile was used at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min: 0–1.3 min, 0% ACN; 1.3–2.5 min, 0–85% ACN; 2.5–4.0 min, 85% ACN; 4.0–4.5 min, 85–0% ACN; 4.5–12.0 min, 0% ACN. The column temperature was 25 °C. The autosampler was non-thermostatted, but the room temperature was kept at 20–22 °C. After each injection, the autosampler needle was rinsed with ACN to avoid sample cross-contamination.

Sample preparation

Samples were prepared by protein precipitation with TCA. One hundred µL of serum was mixed with 10 µL of the IS (3-NT in water, 750 µM) and 10 µL of TCA (360 g/L). The mixture was vigorously vortexed, cooled for 10 min at − 20 °C, shaken for 10 min at 4 °C (850 rpm), and centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C (40,930×g). The supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC vial, and 50 µL were injected into the column.

Due to the known instability of NEO in the presence of UV light (both in aqueous solutions30 and serum31), samples were protected from light at each step of sample processing to avoid photodegradation. Moreover, samples were vortexed immediately after spiking with TCA to avoid a locally high concentration of acid, previously linked with the oxidation of 7,8-dihydroneopterin to NEO and the overestimation of NEO levels by the HPLC methods.32 In our method, the final concentration of TCA in the mixture was 30 g/L, and samples were kept at low temperatures during processing. This concentration of TCA and low temperatures were previously proven33 to give comparable NEO concentrations in the HPLC and the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs).

Calibration curves

As NEO is an endogenous molecule, a mixture of 2% BSA in PBS was used to prepare calibration curves and quality control samples (QCs). Calibration standards (12.5–400 nM) and QCs were prepared by diluting NEO aqueous working solutions with 2% BSA in PBS and were kept at − 80 °C in 125 µL aliquots. Working solutions were kept in a cooling rack during processing due to poor NEO stability (Fig. S1). After thawing at room temperature, calibrators and QCs followed the same sample preparation procedure described for serum. Calibration curves were constructed as a peak area ratio of NEO and IS vs. the nominal concentrations, and log–log regression was used for calculations.

Method validation

The method was validated according to the ICH guidelines34 (The International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) with some modifications due to the endogenous nature of the analyte. Detailed validation data are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Statistics

The continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations (STDs) or medians (interquartile ranges), depending on the results from the Shapiro–Wilk test. The categorical data were expressed as numbers (%). The differences between the groups were assessed using the Student t-test, the Mann–Whitney U test, the Kruskal–Wallis test, the Fisher’s exact test, or the Chi-squared test, as appropriate. Equal distribution of variances was confirmed by an F-test. Differences in NEO levels at specific time points (NEO.1–NEO.4) compared to baseline (NEO.0) were assessed with the Wilcoxon test.

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to select the best cut-offs for NEO levels to discriminate between the long-term responders (clinical benefits ≥ 12 months) and patients who lacked the long-term benefits of treatment. Based on the serum NEO concentrations, participants were divided into low- and high-NEO status groups. Then, the logistic regression analysis was adopted to confirm NEO status as a predictor of the long-term treatment benefits. Only predictors significant in the univariable model were assessed in the stepwise multivariable model. The adjusted odds ratios (ORs) from the multivariable models and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported.

The survival analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of NEO status on PFS, TTF, and OS. The correlations between the survival data and NEO concentrations were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. The Cox proportional regression analysis assessed whether NEO status could be an independent prognostic factor of the long-term benefits of anti-PD-1/PD-L1s. The univariable and multivariable regression analyses were performed, and the hazard ratios (HRs) or adjusted HRs (depending on the model), along with their 95% CI, were reported. Only variables significant in the univariable model were considered in the stepwise multivariable model.

The statistical analysis was done using the MedCalc software (version 22.019, Ostend, Belgium). Graphs were prepared with MedCalc or the Statistica software (version 13.3, Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). In all analyses, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated based on the general data regarding serum NEO and lung cancer. Due to the innovative character of the study, no data for patients treated with the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs were available at the time of planning the study. The following assumptions were made:

-

1.

We expected that the NEO levels in long-term responders might be around 70% of those in patients without the long-term benefits. Previously, in lung cancer patients, serum NEO was 8.6 nM in survivors and 12.1 nM in non-survivors.23

-

2.

Considering that only patients with advanced NSCLC would be included in our study, we assumed that STDs of NEO levels for both groups would be about 40% of their mean. Serum NEO concentrations in lung cancer are characterized by high variability.23 However, the variability was expected to be lower in patients with a similar cancer stage. Previously, STD was around 40%–50% of the mean in patients with small and/or non-small cell lung cancer and unknown cancer stage.22,24

-

3.

The 1-year PFS rates after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs range from 13.2 to 40.3% in advanced NSCLC, depending on the treatment line and PD-L1 status.35 Thus, we expected that the number of patients without the long-term (≥ 12 months) benefits in the current study would be at least 3 times higher than long-term responders.

The calculated minimum sample size was 50 (13 long-term responders and 37 patients who lacked the long-term benefits of treatment), with a type I error of 5% and a statistical power of 80%.

Results

Patients’ characteristics and general efficacy data

One hundred and three NSCLC patients were enrolled, including 59 patients dosed with PEMBRO (anti-PD-1 drug) and 44 patients dosed with ATEZO (anti-PD-L1 drug). Twenty patients from the PEMBRO subgroups (19.4% of the study population) were concurrently treated with chemotherapy. Most of the participants declared to be former (55.6%) or current smokers (36.4%), with only eight categorized as never smokers (8.1%). Among the NSCLC histological subtypes, the most common was adenocarcinoma (57.3%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (34.0%) and not otherwise specified NSCLC (7.8%). One patient had another type of NSCLC. The general characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

No clinical benefits of immunotherapy were recorded in 40.8% of patients. Half of them (57.1%) were not evaluated for response due to death or early discontinuation of the anti-PD1/PD-L1 treatment. The long-term benefits (≥ 12 months) were observed in one-fifth of patients, with eleven (47.8%) presenting PR as their best response. The median PFS in the entire population was 5.7 months (95% CI 4.3–6.3), median TTF–5.0 months (95% CI 4.2–6.0), and median OS–14.2 months (95% CI 8.9–19.1).

Characterization of long-term responders

The long-term responders did not differ from the rest of the study population in terms of age, BMI, sex, smoking status, administered anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drug, treatment modality (monotherapy vs. chemoimmunotherapy), or treatment line. However, they were more frequently diagnosed with adenocarcinoma and presented a higher objective response rate compared to other patients (Table 2).

Neopterin levels in the study population

In total, 400 serum samples were assessed for NEO concentrations. All results were within the calibration range. The medium NEO concentration at baseline (before the first dose of the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drug) was 59.9 (37.8–79.4) nM. The median on-treatment NEO levels were: 75.1 (52.8–101.7) nM at the end of the 1st cycle (NEO.1), 75.5 (52.0–109.1) nM at the end of the 2nd cycle (NEO.2), 71.6 (49.9–93.8) nM at the end of the 3rd cycle (NEO.3), and 70.8 (49.6–103.2) nM at the end of the 4th cycle (NEO.4). The median on-treatment NEO levels in the study population were consistently higher than the baseline values. NEO levels did not depend on age, BMI, sex, smoking status, NSCLC subtype, or objective response (Figs. S4–S8). The only exception was NEO.0, significantly higher in younger participants (the median values of 71.4 and 54.6 nM for the < 65 and ≥ 65-year-old patients; Fig. S4).

Neopterin levels in long-term responders

When stratified by achieving the long-term benefits of treatment, NEO levels were consistently lower in long-term responders (Fig. 1). The difference reached significance at the end of the 3rd and 4th cycles. The median NEO.3 levels were 58.8 (41.9–71.6) nM and 77.8 (55.5–102.3) nM for patients who achieved and lacked the long-term benefits of treatment, respectively (p < 0.05). The corresponding NEO.4 levels were 52.9 (41.6–63.9) nM and 77.6 (59.0–117.3) nM (p < 0.005).

Neopterin concentrations at baseline (NEO.0) and at the end of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th cycles (NEO.1–NEO.4) in NSCLC patients dosed with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors stratified by the long-term benefits of treatment (≥ 12 months). The results are presented as medians (markers) with interquartile ranges (whiskers). The significant differences between long-term responders and patients without durable benefits are highlighted with red asterisks. The differences in the on-treatment levels compared to baseline values for patients without benefits are shown with the connecting lines. There were no significant differences in the on-treatment NEO levels compared to baseline values in long-term responders.

In patients who did not achieve the long-term benefits, NEO concentrations significantly increased after the initiation of the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment and remained elevated for the entire period of NEO monitoring. In long-term responders, only a trend toward higher NEO concentrations after the start of immunotherapy was noticed, but the concentrations returned to the baseline values by the end of the 3rd cycle (Fig. 1).

Cut-offs for identifying long-term responders

The best cut-offs for NEO levels to identify long-term responders were established with ROC analysis. The ROC-derived cut-off for NEO.3 was 71.65 nM (area under the curve, AUC = 0.664, 95% CI 0.541–0.772, p < 0.05), with a sensitivity of 80.0% and specificity of 60.0%. The ROC-derived cut-off for NEO.4 was 66.84 nM (AUC = 0.747, 95% CI 0.612–0.853, p < 0.001) with a sensitivity of 88.2% and specificity of 69.2%.

The stepwise logistic regression revealed that low-NEO status (NEO.3 ≤ 71.65 nM and NEO.4 ≤ 66.84 nM) was the only prognostic factor of long-term benefits of the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment. Low NEO.3 and NEO.4 increased the odds for long-term benefits about 12 times (OR = 11.70, 95% CI 3.24–42.28; p < 0.001). Other factors that distinguished long-term responders from the rest of the study population (i.e., NSCLC subtype and achieving an objective response; Table 2), even though significant in the univariable model, did not meet the selection criteria in the multivariable model (p < 0.05 for entry and p > 0.1 for elimination).

Survival analysis

The survival analysis (Fig. 2) showed that patients with low-NEO status had longer PFS and TTF. The estimated median PFS was 17.3 months (95% CI 6.3–41.7) for the low-NEO group and 5.9 months (95% CI 4.4–7.3) for the high-NEO group. The corresponding median TTF values were 16.3 months (95% CI 6.3–29.7) and 5.5 months (95% CI 4.4–6.5). These observations were independent of the administered drug (Fig. S9): in patients treated with ATEZO, the median PFS and TTF were 2.8 times longer in the low-NEO group than in the high-NEO group, while in a PEMBRO cohort, these values were 2.6 and 2.8. Low NEO concentrations did not significantly impact OS in the entire population (p = 0.0742 from the log-rank test) or in a subgroup analysis (Fig. S9). However, a clear trend toward longer survival with low-NEO status was noticed, especially in the PEMBRO subgroup (27.8 vs. 16.2 months, p = 0.05, Fig. S9f).

Kaplan–Meier curves for (a) progression-free survival (PFS) and (b) time to treatment failure (TTF) for NSCLC patients with low- and high-NEO status dosed with the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs. Low-NEO status was defined as serum neopterin concentrations ≤ 71.65 nM at the end of the 3rd cycle (NEO.3) and ≤ 66.84 nM at the end of the 4th cycle (NEO.4).

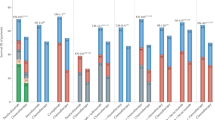

The Cox regression confirmed low-NEO status as a prognostic factor of longer PFS and TTF (Fig. 3). The survival data (PFS and TTF) were not influenced by the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drug regimen (ATEZO vs. PEMBRO), treatment modality (monotherapy vs. chemoimmunotherapy), or treatment line (1st line vs. 2nd line). In the multivariable stepwise Cox regression (p < 0.05 for entry and p > 0.1 for elimination), low-NEO status was the only prognostic factor of PFS, while TTF was affected by low-NEO status, patient’s sex, and objective response. Patients with low-NEO status had a 3.0 times lower hazard of progression (HR = 0.327, 95% CI 0.171–0.625, p < 0.001) and a 2.2 times lower hazard of treatment failure (adjusted HR = 0.450, 95% CI 0.244–0.829; p < 0.05) than patients with high-NEO status. Objective response reduced the hazard of treatment failure 2.6 times (adjusted HR = 0.387, 95% CI 0.186–0.804, p < 0.05), while male sex increased this hazard 1.8 times (adjusted HR = 1.818, 95% CI 1.033–3.201, p < 0.05).

Forest plots for the univariable Cox regression analysis for a) progression-free survival (PFS) and b) time to treatment failure (TTF) among NSCLC patients treated with the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs. Low-NEO status was defined as serum neopterin concentrations ≤ 71.65 nM at the end of the 3rd cycle (NEO.3) and ≤ 66.84 nM at the end of the 4th cycle (NEO.4). Data are presented as hazard ratios, HR (markers) along with their 95% confidence intervals (whiskers).

In the univariable model, OS was affected by sex, NSCLC subtype, concurrent chemotherapy, and the fact of the objective response without the impact of NEO status (data not shown). Lower hazard of death was observed in females (adjusted HR = 0.549; 95% CI 0.344–0.874, p < 0.05), patients with adenocarcinoma (adjusted HR = 0.481; 95% CI 0.305–0.759, p < 0.005), and those who achieved the objective response (adjusted HR = 0.409, 95% CI 0.219–0.763, p < 0.005). Patients treated with concurrent chemotherapy had a 1.9 times higher hazard of death than those treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1s monotherapy (adjusted HR = 1.895, 95% CI 1.082–3.318, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Blood-based molecules are widely assessed as potential biomarkers of successful therapy with ICIs. Their advantages include easy access, the possibility of frequent sampling, and the fact of reflecting the dynamic changes in the whole-body immunological response. Here, we demonstrate that serum NEO concentrations measured early after the initiation of treatment could successfully distinguish the long-term responders to the PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Low-NEO status increased the odds of ≥ 12-month benefits almost twelve times, decreased the hazard of NSCLC progression three times, and decreased the hazard of treatment failure 2.2 times, regardless of the objective response.

The first information about NEO detection in human body fluids dates back to 1967 when NEO was isolated from human urine.36 Since then, NEO has been measured in various biological matrices, including the common ones like serum,20,21,22,23,24,37,38,39 plasma,26,40 or urine,41,42 but also less typical, such as tears.37 While NEO levels in most of the matrices reflect local inflammation (e.g., high NEO levels were detected in wound secretions,43 in cerebrospinal fluid in active neuroinflammation,44 in bronchoalveolar lavage in tuberculosis,24 or oral and gingival crevicular fluids in periodontal diseases19), much evidence indicates that NEO levels in blood and urine show the whole body’s immune response. Accordingly, increased NEO formation in those matrices was detected in conditions associated with immune activation, such as allograft rejections, multiple autoimmune and viral diseases, and cancer.15,18

High blood or urinary NEO levels have been identified as a predictor of poor prognosis in various cancers, including gynecological, gastrointestinal, and prostate cancers, hematological malignancies, or melanoma.15 Elevated NEO levels predict worse outcomes also in lung cancer, both in surgical cases and in patients treated over the last decades with various protocols.23,41,45 As immunotherapy is supposed to restore the blunted immune system,2 NEO seems to be a perfect biomarker also for predicting the efficacy of ICIs. However, data concerning this new treatment are scarce. The available reports linked high blood NEO before ICIs with earlier progression or death in renal cell carcinoma27 and NSCLC25,26 and high on-treatment levels with worse outcomes in melanoma and NSCLC.25 Although our observations about the on-treatment NEO concentrations were similar, we did not find enough evidence to indicate high baseline NEO as a predictor of shorter PFS or OS. Notably, we included more NSCLC patients treated with the ICIs (n = 103) than previous research groups (n = 5326 and n = 16 or n = 45, depending on the sampling time25).

On the other hand, we confirmed that serum NEO levels measured relatively early after the treatment initiation (about 2–3 months) could predict the benefits lasting ≥ 12 months. Despite the initial response, many patients treated with the ICIs progress during the follow-up monitoring.3 We observed a similar pattern: 59.2% of patients presented at least SD as their best response, but only one-third of them were long-term responders (Table 1). Therefore, measuring serum NEO could be an easy and fast way to indicate NSCLC patients needing other, additional, or more personalized therapy to succeed during the treatment. This indicates the clinical relevance of NEO and its potential role in routine practice to improve the treatment outcomes after anti-PD-1/PD-L1s.

According to our knowledge, this is the first study that monitored longitudinally serum NEO levels in NSCLC patients dosed with the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs. Due to rich sampling, we could detect the specific changes in NEO levels occurring during the first three months of treatment. Other studies with patients dosed with ICIs usually focused on the baseline NEO levels.26,27 The exception was a recent study by Musaelyan and colleagues,25 enrolling a small cohort of NSCLC patients (n = 16) who were monitored at baseline and after two and six months of immunotherapy. The Authors showed that serum NEO increased after introducing anti-PD-1/PD-L1s.25 Although we noticed a similar pattern in the study population as a whole, we also revealed that this trend was true only for the subgroup that lacked the long-term benefits of treatment. In contrast, in long-term responders, the slightly elevated NEO levels quickly returned to the baseline values by the end of 3rd cycle (Fig. 1). Thus, our study adds to the existing knowledge and helps to understand better the phenomena associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy. It also highlights the importance of sampling time due to the kinetic changes in NEO concentrations after introducing PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

The increase in the on-treatment NEO levels, although much less pronounced in the case of the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs, corroborates with previous findings regarding cancer immunotherapy with interleukin-2 (IL-2),46,47 IFN-γ,48 and IFN-α.49 These molecules were used in the early attempts to restore immune functions through the Th1 cells.2 In contrast, the on-treatment changes in NEO levels were not recorded in NSCLC patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (assessed in serum)25 or EGFR inhibitors (in urine42).

Notably, high NEO levels at the end of the 3rd (NEO.3) and 4th (NEO.4) cycles were not directly associated with PD, which would lower their potential as a biomarker as they were measured around the time of the first radiological response. In fact, NEO levels did not differ in patients with no benefit of treatment (i.e., presenting mostly PD) and short-term benefits (i.e., presenting at least SD < 12 months). However, we found lower NEO levels in patients with long-term benefits compared to those with no- or short-term benefits (Fig. S10). Different patterns in NEO concentrations in patients with and without the long-term benefits (Fig. 1) might reflect the progressing immunological imbalance in non- and short-term responders. As NEO is almost exclusively produced by macrophages,15 high NEO levels in patients with worse response most likely reflected the chronic macrophage stimulation and failure of the host to control the tumor, i.e., poor efficacy of implemented immunotherapy.

In healthy volunteers50 and blood donors,51 serum NEO concentrations change with age, gender, BMI, and smoking status. We did not confirm any of these factors to impact significantly NEO levels in our population (Figs. S4–S8). The only exception was baseline NEO higher in younger participants (Fig. S4), which was in contrast to observations in healthy people.50,51 At the same time, we confirmed similar NEO status in different NSCLC subtypes, which corroborated previous findings.24

Unexpectedly, we observed higher blood NEO concentrations (medians ~ 60–75 nM) than reported previously for advanced NSCLC patients dosed with ICIs (~ 10–15 nM).25,26 One of the possible reasons could be the acidic protein precipitation used by our group for the sample clean-up before the HPLC analysis. This procedure can increase NEO concentrations due to the oxidation of 7,8-dihydroneopterin to NEO.32 However, as mentioned in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section, we followed the protocol validated previously against the ELISA assay.33 Thus, a different detection type and sample clean-up was most likely not the cause of the observed differences. Furthermore, the mean/median blood NEO concentrations in NSCLC vary greatly in the literature and range from less than 10 nM (in most scientific papers considered as a cut-off for healthy people19) to 55 nM (for the ELISAs,20,22,23,25,39 radioimmunoassay24 and chromatographic method not using acids during sample preparation26), so our results are close to the upper limit of this range. Some inconsistencies between the reported concentrations might result from the different cancer stages in the published studies. In fact, although NEO is not a typical tumor marker (as it is not produced by the tumor cells),41 its concentrations strongly depend on the cancer stage, both in NSCLC20 and other tumors.20,52,53

In various conditions, blood NEO concentrations (serum and plasma) positively correlate with other immune activation molecules, e.g., the soluble form of the unit α of the IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R, known as sCD25)38,40,46,54 and soluble form of the CD8 antigen (sCD8).38,54,55 Such an association was shown for sCD25 and/or sCD8 in HIV (human immunodeficiency virus),54,55 systemic lupus erythematosus,38 depression,40 and cancer immunotherapy with IL-2,46 but data for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are lacking. As both molecules are within our scope of interest and we have already determined their concentrations in dozens of patients included in the current study,9,10 we tested correlations between serum NEO levels and sCD25 and sCD8. The analyses showed that, in contrast to sCD8, the on-treatment changes in sCD25 and NEO were exactly parallel, which was confirmed by the positive Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between sCD25 and NEO (Fig. 4). Revealed correlation might indicate that macrophages are involved in sCD25 release during anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy, as suggested previously for cancer treatment with IL-2.46

Kinetic changes in serum NEO, sCD25, and sCD8 in NSCLC patients undergoing therapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1s (Fig. a and c) and correlation between tested molecules (Fig. b and d). Samples were collected at baseline and at the end of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th cycles from patients dosed with ATEZO or PEMBRO. In total, 249 serum samples were determined for NEO & sCD25 comparison (Fig. a and b) and 252 serum samples for NEO & sCD8 (Fig. c and d). Data in Fig. a and c are presented as medians (markers) along with the interquartile ranges (whiskers). A similar pattern of changes was observed for NEO and sCD25 (Fig. a) and not for NEO and sCD8 (Fig. c). The results were confirmed by Spearman’s test: there was a significant positive correlation between NEO and sCD25 (Fig. b) and no correlation between NEO and sCD8 (Fig. d).

Conclusions

The study showed that the on-treatment serum NEO levels should be considered a potential biomarker of the successful anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in NSCLC. Low NEO concentrations at the end of the 3rd and 4th cycles differentiated patients with and without long-term benefits of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy.

Study limitations

The presented study has some limitations. Firstly, some participants from the PEMBRO subgroup were treated with chemoimmunotherapy. We enrolled 20 patients on combination therapy as previous reports showed that chemotherapy25,39 (including platinum-based chemotherapy,25 which was used in our patients) did not significantly alter NEO levels in lung cancer.

Moreover, samples from two clinical sites were not collected simultaneously, which resulted in a different follow-up time. However, the proportion of long-term responders, patients with low-NEO status, and the patients’ characteristics mostly did not differ between the sites (Fig. S11). Thus, we concluded that the clinical outcomes should also be comparable. The only exception was smoking status (more current smokers recruited from hospital 2), which impacted neither the survival data (Fig. 3) nor the NEO levels (Figs. S4–S8).

Another aspect to consider is the worldwide pandemic with COVID-19. Most samples from hospital 1 were collected before February 2020 (i.e., before the pandemic outbreak), while samples from hospital 2 started to be collected in January 2022 (i.e., at the time when SARS-CoV-2, responsible for COVID-19, was already widely present in society). In turn, NEO concentrations are elevated in viral infections,56 including SARS-CoV-2, and were even suggested as a biomarker of COVID-19 severity.57 Our patients were not routinely tested for COVID-19. But, no patient showed symptoms of any active infection before dosing. Also, the survival data (from both clinics) might be biased by the COVID-19 outbreak: even the successful anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment could have been disrupted by COVID-19 infection and deterioration of the patient’s condition or death. Unfortunately, this aspect was impossible to control and will impact all human studies conducted after February 2020. Moreover, we did not have access to the causes of death, so all recorded deaths (from any cause) were included in the survival analysis.

Lastly, even though each sample was collected pre-dose, the time between the two doses sometimes exceeded 21 days. The dose delay was usually due to the patient’s condition or lab results, rarely random effects. Also, some patients discontinued treatment before all planned samples had been collected. As our study shows real-world data, this effect was unavoidable. However, the separate analysis conducted only for patients who provided all five sera and were not delayed in the next dose more than three days (n = 39) showed comparable results. The pre-treatment NEO concentrations could not discriminate long-term responders from patients who lacked the long-term benefits, and significant differences between these groups began around the second and third month of immunotherapy (data not shown).

Data availability

The most relevant data supporting the study’s findings are presented in the main manuscript or Supplementary Materials. Other data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3-NT:

-

3-Nitro-L-tyrosine

- ACN:

-

Acetonitrile

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- anti-PD-1/PD-L1s:

-

Drugs directed against the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway

- ATEZO:

-

Atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1 drug)

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CR:

-

Complete response

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- HPLC-FLD/UV:

-

HPLC method with fluorescence and ultraviolet detection

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICH:

-

The International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use

- ICI:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IL-2:

-

Interleukin-2

- INF-γ:

-

Interferon-gamma

- IS:

-

Internal standard

- NEO:

-

Neopterin

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NS:

-

Non-significant

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1:

-

Ligand 1 for programmed cell death protein 1

- PEMBRO:

-

Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 drug)

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- QC:

-

Quality control sample

- RECIST:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- ROC curves:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curves

- sCD8:

-

Soluble form of the CD8 antigen

- sCD25 (sIL-2R):

-

Soluble form of the unit α of the IL-2 receptor

- SIRI:

-

Systemic inflammation response index

- TAMs:

-

Tumor-associated macrophages

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- STD:

-

Standard deviation

- TCA:

-

Trichloroacetic acid

- TTF:

-

Time to treatment failure

- UV:

-

Ultraviolet

References

Li, L. et al. Effects of immune cells and cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 88, 106939 (2020).

Saab, S. et al. Insights into lung cancer immune-based biology, prevention, and treatment. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00159 (2020).

Kunimasa, K. & Goto, T. Immunosurveillance and immunoediting of lung cancer: Current perspectives and challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 597 (2020).

Memmott, R. M., Wolfe, A. R., Carbone, D. P. & Williams, T. M. Predictors of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1086–1098 (2021).

Onoi, K. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer treatment: A review. J. Clin. Med. 9, 1362 (2020).

Zhou, S. & Yang, H. Immunotherapy resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer: From mechanism to clinical strategies. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1129465 (2023).

Tsai, Y.-T., Schlom, J. & Donahue, R. N. Blood-based biomarkers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint blockade. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 43, 82 (2024).

Ancel, J. et al. Soluble biomarkers to predict clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer treated by immune checkpoints inhibitors. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1171649 (2023).

Siemiątkowska, A. et al. Serum sCD25 protein as a predictor of lack of long-term benefits from immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: A pilot study. Cancers 13, 3702 (2021).

Siemiątkowska, A. et al. Low on-treatment levels of serum soluble CD8 (sCD8) predict better outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 72, 1853–1863 (2023).

Zheng, M. Systemic inflammation shapes clinical outcomes in response to immune checkpoint blockade treatment: Moving toward optimizing antitumor immunity. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e006462 (2023).

Tang, C. et al. The systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) predicts survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy and the construction of a nomogram model. Front. Immunol. 15, 1516737 (2024).

Austermann, J., Roth, J. & Barczyk-Kahlert, K. The good and the bad: Monocytes’ and macrophages’ diverse functions in inflammation. Cells 11, 1979 (2022).

Sedighzadeh, S. S., Khoshbin, A. P., Razi, S., Keshavarz-Fathi, M. & Rezaei, N. A narrative review of tumor-associated macrophages in lung cancer: Regulation of macrophage polarization and therapeutic implications. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 1889–1916 (2021).

Melichar, B. et al. Neopterin as a biomarker of immune response in cancer patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 5, 280 (2017).

Sica, A. et al. Macrophage polarization in tumour progression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 18, 349–355 (2008).

Mei, J. et al. Prognostic impact of tumor-associated macrophage infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7, 34217–34228 (2016).

Murr, C., Widner, B., Wirleitner, B. & Fuchs, D. Neopterin as a marker for immune system activation. Curr. Drug Metab. 3, 175–187 (2002).

Heneberk, O., Wurfelova, E. & Radochova, V. Neopterin, the cell-mediated immune response biomarker, in inflammatory periodontal diseases: A narrative review of a more than fifty years old biomarker. Biomedicines 11, 1294 (2023).

El-Akawi, Z. J., Abu-Awad, A. M., Sharara, A. M. & Khader, Y. The importance of alpha-1 antitrypsin (alpha1-AT) and neopterin serum levels in the evaluation of non-small cell lung and prostate cancer patients. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 31, 113–116 (2010).

Yuksekol, I. et al. Urinary neopterin measurement as a non-invasive diagnostic method in pulmonary tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. Off. J. Int. Union Tuberc. Lung Dis. 7, 771–776 (2003).

Engin, A. B., Ozkan, Y., Fuchs, D. & Yardim-Akaydin, S. Increased tryptophan degradation in patients with bronchus carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 19, 803–808 (2010).

Yalcin, S. et al. Prognostic effects of SuPAR and neopterin levels on patients with lung cancer. Pteridines 31, 136–141 (2020).

Mohamed, K. H. et al. BAL neopterin: A novel marker for cell-mediated immunity in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and lung cancer. Chest 119, 776–780 (2001).

Musaelyan, A. A. et al. Inflammatory and autoimmune predictive markers of response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in NSCLC and melanoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 24, 1–12 (2022).

Azuma, K. et al. Clinical significance of plasma-free amino acids and tryptophan metabolites in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving PD-1 inhibitor: A pilot cohort study for developing a prognostic multivariate model. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e004420 (2022).

Spisarova, M. et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and progression during immunotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Vivo Athens Greece 37, 393–399 (2023).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use information - glossary. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/tobacco/tobacco_glossary.htm.

Vignoni, M., Cabrerizo, F. M., Lorente, C. & Thomas, A. H. New results on the photochemistry of biopterin and neopterin in aqueous solution. Photochem. Photobiol. 85, 365–373 (2009).

Laich, A., Neurauter, G., Wirleitner, B. & Fuchs, D. Degradation of serum neopterin during daylight exposure. Clin. Chim. Acta 1–2, 175–178 (2002).

Werner, E. R., Fuchs, D., Hausen, A., Reibnegger, G. & Wachter, H. Simultaneous determination of neopterin and creatinine in serum with solid-phase extraction and on-line elution liquid chromatography. Clin. Chem. 33, 2028–2033 (1987).

Midttun, Ø., Hustad, S. & Ueland, P. M. Quantitative profiling of biomarkers related to B-vitamin status, tryptophan metabolism and inflammation in human plasma by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. RCM 23, 1371–1379 (2009).

European Medicines Agency. ICH guideline M10 on bioanalytical method validation—Step 5. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-m10-bioanalytical-method-validation-scientific-guideline.

Man, J., Millican, J., Mulvey, A., Gebski, V. & Hui, R. Response rate and survival at key timepoints with PD-1 blockade vs chemotherapy in PD-L1 subgroups: Meta-analysis of metastatic NSCLC trials. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 5, pkab012 (2021).

Sakurai, A. & Goto, M. Neopterin: Isolation from human urine. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 61, 142–145 (1967).

Baydar, T., Kemer, O. E., Kilicarslan, B., Cardak, A. & Girgin, G. Detection of neopterin in tear samples. Pteridines 27, 13–16 (2016).

Samsonov, M. Y. et al. Serum soluble markers of immune activation and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 4, 29–32 (1995).

Crintea, A. et al. Assessment of specific tumoral markers, inflammatory status, and vitamin D metabolism before and after the first chemotherapy cycle in patients with lung cancer. Biology 11, 1033 (2022).

Maes, M., Bosmans, E., Scharpé, S., D’Hondt, P. & Desnyder, R. Plasma soluble interleukin-2-receptor in depression: Relationships to plasma neopterin and serum IL-2 concentrations and HPA-axis activity. Eur. Psychiatry 10, 397–403 (1995).

Prommegger, R. et al. Neopterin: A prognostic variable in operations for lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 70, 1861–1864 (2000).

Kalabova, H. et al. Urinary neopterin in patients treated with gefitinib. Pteridines 18, 95–100 (2007).

Mergancová, J. et al. Concentrations of neopterin, kynurenine and tryptophan in wound secretions of patients with breast cancer and malignant melanoma: A pilot study. Pteridines 28, 205–211 (2017).

Yan, J. et al. CSF neopterin, quinolinic acid and kynurenine/tryptophan ratio are biomarkers of active neuroinflammation. eBioMedicine 91 (2023).

Kronberger, P. et al. Predictive value of urinary neopterin in patients with lung cancer. 33, 831–838 (1995).

Lissoni, P. et al. Increase in soluble interleukin-2 receptor and neopterin serum levels during immunotherapy of cancer with interleukin-2. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 27, 1014–1016 (1991).

Kleinknecht, S., Bichler, K.-H. & Strohmaier, W. L. Influence of immunotherapy (IL2 + LAK + inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis) on peripheral blood immune parameters and in vitro cytokine production in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Int. 50, 121–128 (2010).

Höbarth, K., Szabo, N., Hallas, A., Aulitzky, W. & Marberger, M. Serum neopterin as a parameter for monitoring the course of renal cell carcinoma during interferon-gamma therapy. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 70, 241–244 (1994).

Van Gool, A. R. et al. Serum amino acids, biopterin and neopterin during long-term immunotherapy with interferon-alpha in high-risk melanoma patients. Psychiatry Res. 119, 125–132 (2003).

Spencer, M. E. et al. Serum levels of the immune activation marker neopterin change with age and gender and are modified by race, BMI, and percentage of body fat. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 65A, 858–865 (2010).

Schennach, H. et al. Factors influencing serum neopterin concentrations in a population of blood donors. Clin. Chem. 48, 643–645 (2002).

Yoshida, N. et al. Serum Neopterin levels in renal cell carcinoma. Pteridines 11, 133–136 (2000).

Yildirim, Y. et al. Serum neopterin levels in patients with breast cancer. Med. Oncol. 25, 403–407 (2008).

Griffin, D. E., McArthur, J. C. & Cornblath, D. R. Neopterin and interferon-gamma in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with HIV-associated neurologic disease. Neurology 41, 69–74 (1991).

Tilz, G. P. et al. Association between serum-soluble CD8 levels and parameters of immune activation in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin. Investig. 70, 662–664 (1992).

Eisenhut, M. Neopterin in Diagnosis and Monitoring of Infectious Diseases. J. Biomark. 2013, 196432 (2013).

Rasmi, Y. et al. The importance of neopterin in COVID-19: The prognostic value and relation with the disease severity. Clin. Biochem. 104, 1–12 (2022).

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and hospital or laboratory staff involved in the project. We express special gratitude to Agnieszka Nowak from the Department of Physical Pharmacy and Pharmacokinetics for her technical assistance during neopterin assays. This research was supported by Poznan University of Medical Sciences (grant ProScience Young Scientists 2022 awarded to AS, Grant No. NMN0000060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, methodology, investigation (HPLC analyses), formal analysis (statistics), visualization (tables and graphs), writing–original draft; BKK: resources (patient recruitment and assessment of their response to treatment), supervision of the clinical part of the project; MB: resources (patient recruitment and assessment of their response to treatment), supervision of the clinical part of the project; KKN: validation, writing–review & editing; PP: investigation (HPLC analyses); IGG: resources (patient recruitment and assessment of their response to treatment); FG: supervision of the analytical part of the study, writing–review & editing. All Authors have read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MB—honoraria, consulting or advisory role and travel, accommodations, expenses from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche/Genentech, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi; AS, BKK, KKN, PP, IGG, and FKG declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siemiątkowska, A., Kuźnar-Kamińska, B., Bryl, M. et al. Low serum neopterin early indicates durable benefits of atezolizumab and pembrolizumab therapy in advanced lung cancer. Sci Rep 15, 13078 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97792-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97792-9