Abstract

Lithium is commonly prescribed for bipolar disorder due to its proven efficacy on patients. Despite this effectiveness, the molecular mechanisms underlying its action remain poorly understood, as it appears to influence numerous unrelated pathways. We propose that these diverse effects may stem from a specific physicochemical event: the binding of lithium cations to phospholipid headgroups. In model membrane systems enabling direct observation of the lithium effects on lipid bilayers, we reveal that lithium binding stiffens the membrane, subsequently altering membrane protein activities. This mechanical impact of lithium links existing rationales, drawing a way to decipher the complex lithium effect in bipolar disorder (BD). To illustrate this global effect of lithium, we use the example of intracellular trafficking, a ubiquitous mechanism involving membrane reorganization in all organelles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

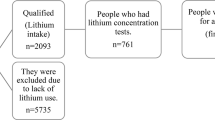

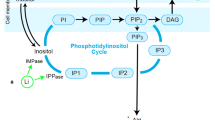

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by alternating manic and depressive episodes. During manic phases, patients are euphoric, hyperactive, exhibit racing thoughts and impulsive behavior leading to putting themselves at risk. While in depressive episodes, patients are sad, lack energy and feel a deep sense of hopelessness, possibly experiencing suicidal thoughts. Lithium treatment has been effectively used for decades to treat or prevent the onset of mania or depression. In search of a specific target of lithium, several apparently unrelated downstream effects have been clearly identified. Notably, lithium appears to alter dopamine release1,2, alter the activity of voltage-gated sodium channels3, increases the expression of Na+/K+ ATPase4,5,6, affect G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) activity7, modify lipid metabolism6,8,9 and inhibit inositol monophosphatase (IMPase)5,10,11, which is involved in the phosphatidylinositol metabolism. Additionally, many studies have focused on the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3)12,13,14,15, a highly-regulated kinase involved in numerous intracellular pathways. Inhibition of GSK3 by lithium has been shown to attenuate manic and depressive episodes16,17,18. However, GSK3 affinity for lithium is weaker than the therapeutic lithium concentration in the cell, which is around 1 mM, mitigating its contribution as the main target of lithium19,20. More recently, transcriptomic approaches, aimed at providing a more global understanding of BD have revealed abnormal expression of hundreds of genes in BD phenotype cells21,22,23. In Li-responsive cells, the expression of several hundred genes is altered following lithium uptake, part of them being membrane channels, exocytosis machinery, lipid metabolism related enzymes and signaling pathway proteins24. Due to this systemic rather than specific effect, the precise biochemical mechanisms underlying its action remain unclear. These observations suggest a broader, more global effect of lithium on the cell20,25,26.

In parallel with these biomedical observations, it has been suggested that lithium, along with other cations, affects lipid bilayer properties27. Lithium has been shown to interact with phospholipid headgroups with higher affinity than other physiological cations, except for calcium28,29,30,31,32. This high affinity is not only the consequence of the high surface charge density of lithium, but also reflects the ability of lithium to transiently coordinate to lipid headgroups33,34. Cations coordination occurs primarily through interactions with oxygen in phosphate groups and ester moieties, and can be strengthened by chelation with electron donating moieties of other headgroups, like serine35,36. Cation coordination induces a thickening of the membrane, an increase of lipid melting temperature and packing as well as a reduction of lipid diffusivity37,38,39. Lipid-cation interactions have mechanical consequences on the overall membrane properties, rigidifying its core and modifying surface hydration, hydrophobicity and charge densities40,41,42,43.

Rigidification of the membrane would impair processes requiring important local topological changes, such as membrane fusion or fission, where reaction pathways involve deformation of the lipidic tissue on a nanometer scale44. Furthermore, alterations in membrane properties can lead to important changes for membrane-integral proteins, affecting their spatial distributions, activities and equilibrium conformations45. However, demonstrating such mechanisms for lithium has remained challenging as it requires decoupling the contribution of the putative lithium-protein interactions from that of lithium-membrane interactions. Previous works examining the effect of lithium on membrane-associated proteins, both in vivo or in vitro, have struggled to decorrelate these contributions46,47.

To circumvent such limitations, we employ an approach that allows us to measure the consequences of lipid-lithium interactions on the lipid bilayer. We then study membrane protein-mediated events by placing proteins in a lithium-free environment while maintaining the membrane/lithium interaction. First, we demonstrate that lithium stiffens lipid bilayers even at therapeutic concentrations. Second, we show that membrane remodeling, like membrane fusion, becomes energetically costlier due to lithium. Third, using membrane bilayer fusion mediated by SNAREs (soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) as a case study, we demonstrate that lithium impairs SNARE-mediated membrane fusion without interfering with the SNARE protein activity. SNARE-mediated membrane fusion is a ubiquitous mechanism involved in vesicular trafficking and cell–cell communication48, thus constituting a generic example for the lithium global effect.

Results

Lithium increases membrane stretching modulus

To test the proposition that lithium binding to phospholipids stiffens membranes, we adopt a giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs)-manipulation technique as a means to measure membrane bilayer stretching modulus49. The GUVs were formed in sucrose by electroformation and manipulated with micropipettes (see Materials and Methods). As GUVs were formed in sucrose solution, the GUVs inner leaflet was exposed to sucrose and the outer leaflet was exposed to a buffer of controlled composition. The GUVs were maintained at the tip of the micropipette by hydrostatic aspiration (Fig. 1A top panel). Upon increasing the aspiration, the extension of the GUV protruding inside the micropipette was extended (Fig. 1A lower panel). This elongation results from the stretching of the membrane and, as a direct consequence, induces an increased membrane tension of the GUV. Hence, the stretching ability of the membrane under tension can be quantitatively measured by performing cycles of increasing and decreasing aspiration (Fig. 1B). The relative variation in the membrane surface area is related to the change in surface tension through a proportionality coefficient, the stretching modulus, which is a quantitative measure of the membrane stiffness. We measured this stiffness across an increasing lithium concentration, from 0 mM LiCl (lithium chloride) to 150 mM LiCl, thus changing the lithium concentration for the GUVs outer leaflet. In order to maintain the osmolarity equilibrium between the two sides of the GUVs, the buffer was supplemented with KCl to ensure a fixed monovalent salt total concentration of 150 mM, thereby balancing the 200 mM sucrose inside the vesicle.

Stretching modulus measurements using micropipette aspiration. (A) GUVs formed by electroformation are aspirated in a micropipette. From top to bottom panels, the aspiration of the micropipette increases. The GUV deformed upon aspiration, as can be seen by comparing the membrane elongation inside the micropipette between the top panel and the lower one. (B) Curves of membrane tension in µN/m depending on membrane surface extension α. The slope at high tension corresponds to the stretching modulus of the membrane. To accurately measure the stretching modulus, two aspiration increase and an aspiration decrease ramps were sequentially performed on each GUV to ensure that no hysteresis affects the measurements. (C) Plot of stretching modulus in mN/m depending on the lithium concentration in mM. As lithium concentration increases, stretching modulus increases. Each point corresponds to the average of the slope of N = 15 aspiration increase ramps and error bars are standard errors on the mean (SEM). (D) Table with the values of stretching modulus in mN/m with SEM (middle column) for each lithium concentration tested. The column on the right presents the stretching modulus increase in percent taking as reference the stretching modulus measured without lithium. (E) Scheme of the effect of lithium on stretching membrane ability. Lithium links lipids together, increasing the stretching modulus of the membrane. Thus, for an identical pulling force the deformation of the membrane is lower when lithium is present.

By increasing the lithium concentration, the stretching modulus increases as well (as represented on Fig. 1C). A lithium concentration of 1.5 mM, which is within the therapeutic millimolar range, was sufficient to increase membrane stiffness by 23%, compared to the control 150 mM KCl reference; further increasing the lithium concentration shows that the stiffness does not significantly increase after 15 mM LiCl (Fig. 1D). To illustrate the impact of lithium on the membrane stretching modulus, one can compare its variations with lithium concentration to those observed with increasing cholesterol concentration. Needham and Nunn conducted detailed measurements of the stretching modulus of SOPC/cholesterol bilayers at different molar fractions, ranging from 0 to 58%50. At a lithium concentration of 1.5 mM, the membrane stretching modulus increases by 23%, which corresponds to a cholesterol molar fraction of approximately 25% in the experiments by Needham and Nunn. This suggests that the presence of lithium in the bilayer environment induces changes comparable to a significant alteration in the membrane lipid composition. Notably, the observed stiffening is not associated with a significant change in lipid diffusivity (see Supplementary text, Fig. S4 and Table S1).

The increase of stretching modulus indicates that separating phospholipids from one another becomes energetically more costly as lithium concentration increases. Considering the lithium-mediated lipid bridging effect (i.e., lipid-lithium-lipid) observed in previous molecular dynamics studies30, we interpret the membrane stiffening as a direct consequence of the lipid bridging by lithium (Fig. 1E). Since stiffening occurs at low-millimolar lithium concentrations, this interpretation is consistent with the previously reported millimolar range affinity between phospholipids and lithium51.

Interestingly, the stretching modulus measurement on GUVs implies an asymmetry between the two leaflets, as the inside of the GUVs is exposed to sucrose while the outside is exposed to the monovalent salt buffer. Consequently, only one leaflet is in direct contact with lithium. This appears to be sufficient to affect membrane bilayer properties, suggesting that lithium can exert effects on plasma membrane or organelles even without entering them.

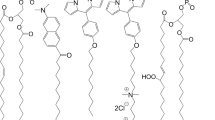

Membrane fusion energy barrier increases with lithium

The stiffening effect of lithium on membranes through lipid bridging suggests that the elementary unit of the lipid bilayer may now be a cluster of transiently-bound lipids. The energetic cost to rearrange such a unit might be higher than for individual lipids, making membrane topological changes more challenging. To validate this hypothesis of increased energy for membrane remodeling, we measured the energy barrier changes during the membrane fusion process at different lithium concentrations. During membrane fusion, a pore needs to open between two apposed membranes, necessitating significant topological changes, including the formation of regions with high local curvature. Deforming membranes on the path to fusion pore opening becomes more difficult as membrane stiffness increases, consequently the total energy required for fusion to occur should increase as well. In order to test experimentally whether lithium increases the main energy barrier for fusion, we employed a well-established lipid mixing assay52 to measure the activation energy for the spontaneous fusion of small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) with and without lithium (Fig. 2A). Nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl-phosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-PE) and rhodamine-PE lipids were incorporated in a first set of SUVs (1.5 mol % each). At this surface concentration, rhodamine effectively quenches the NBD fluorescence. A second set of SUVs contained no fluorescent lipids. These two types of SUVs were mixed at a 1:9 molar ratio (fluorescent: non-fluorescent). When a fluorescent SUV fuses with a non-fluorescent SUV, NBD signal increases due to the two-fold lipid dilution, which reduces NBD quenching by rhodamine (Fig. 2B). The initial slope of the fusion kinetics, obtained by measuring NBD dequenching over time, increases with temperature according to Arrhenius law. Fitting the reaction rate as a function of temperature allows for the determination of the apparent fusion activation energy (Fig. 2C). We measured this fusion kinetics over the range of 27 °C to 47 °C for lithium concentrations ranging from 0 to 15 mM, and found that adding lithium raises the activation energy barrier by approximately 15% with 1.5 mM lithium (Fig. 2D). It demonstrates that membrane fusion is intrinsically hindered by lithium. An increase of 4.5 kBT at 1.5 mM lithium compared to the reference without lithium correspond to a decrease of the reaction rate by approximately 80-fold. The fusion energy barrier starts reaching a plateau at a lithium concentration of 7.5 mM, with an increase in the energy barrier of 10 kBT, corresponding to a drop in the fusion rate by 22,000-fold. Now we can illustrate the effect of lithium on membrane fusion using a concrete timescale: if a single membrane fusion event was occurring in one second, a 1.5 mM concentration of lithium would require more than one minute, and at 7.5 mM lithium, fusion would take as long as 6 h.

Spontaneous fusion energy barrier measurement at changing lithium concentration. (A) Two populations of SUVs were prepared. First, a fluorescent population containing NBD-PE and Rhodamine-PE labelled lipids. The other SUV population does not contain any fluorescent lipid. NBD-PE fluorescence is quenched by the presence of Rhodamine-PE in the vicinity. When a fluorescent vesicle and a non-fluorescent vesicle spontaneously fuse, the fluorescent lipids are diluted inducing a reduction of the quenching effect and therefore an increase in NBD-PE fluorescence. Recording NBD-PE fluorescence over time gives access to the fusion kinetics. (B) Vesicle fusion kinetics over time for vesicle in 150 mM potassium and no lithium at different temperatures. As temperature increases, the initial slope for fusion increases. Fusion advancement at each time point is measured by the average over a triplicate (n = 3) and error bars are SEM. (C) Arrhenius plot from spontaneous fusion kinetics depending on temperature. The slope of the fit in natural log-scale corresponds to the apparent fusion energy barrier of fusion. Each point in the plot is the average of three fusion slopes (n = 3) at a defined temperature and error bars are SEM. (D) Table with activation energy barrier for spontaneous fusion depending on lithium concentration. As lithium concentration increases, fusion activation energy barrier increases. Each point is the average of three slopes of Arrhenius plots (N = 3) and error bars are SEM. In the right column is the fusion energy barrier increase associated for each concentration measured taking as reference the activation energy barrier in absence of lithium.

SNAREs proteins do not compensate lithium effect on fusion.

Membrane fusion cannot spontaneously occur on physiologically relevant timescales. To meet the required timescale in vivo, fusion is accelerated by fusion proteins such as SNAREs, as for the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the neuronal plasma membrane, which occurs on a millisecond timescale53. SNAREpin complexes, composed of a vSNARE (VAMP2) emanating from the synaptic vesicle and a tSNARE complex (Syntaxin1A and SNAP25) from the neuronal target membrane, form coiled-coils that, upon zippering, force the membranes into close apposition and induce their fusion (Fig. 3A). To determine whether the increased activation energy due to the lithium-membrane interaction reduces the efficacy of SNARE-mediated membrane fusion, we investigated the fusion of vesicles mediated by SNAREpins using a specific microfluidic device that mimics the physiological lipid composition of a plasma membrane (Fig. 3B)54,55. This device allows the formation of an asymmetric suspended lipid bilayer functionalized by tSNAREs oriented in the same side of the bilayer. The two leaflets of the bilayer are formed independently before fully zippering and are each exposed to aqueous solutions of controlled compositions. One compartment is an intracellular mimic in which vesicular fusion occurs, with tSNAREs directly facing SUVs bearing vSNAREs (vSUVs) in a potassium buffer. The other compartment is equivalent to the extracellular side and its monolayer is exposed to an aqueous solution with controlled concentrations of lithium. Due to the geometry of this device, SNAREs are spatially separated from lithium exposure, thereby ensuring SNARE activity remains unaffected by the various lithium concentrations in the extracellular equivalent side. Functionalizing vSUVs with hemolysin, one can record fusion pore opening by applying a constant voltage across the suspended bilayer, recording fusion pore opening at single pore resolution (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Lithium effect on SNARE-mediated vesicular fusion on suspended membrane. (A) SNARE proteins are the vSNARE, VAMP2, with a single helical domain, located on the vesicle (green) and the tSNARE, a preassembled Sytaxin1A/SNAP25 dimer with a three helices bundle, located on the target membrane (red, yellow and grey). Upon encountering, vSNARE and tSNARE hybridize in a four-helix coil-coiled called a SNAREpin (second panel). The SNAREpin provides energy upon zippering, facilitating fusion pore nucleation (third panel). In the case of fusion mediated by a low SNAREpin number, the fusion pore is transient and reseals after opening (fourth panel). (B) Scheme of the suspended membrane experimental conditions. On the left, the leaflet compositions for the intracellular equivalent, composed of DOPC:DOPS:DOPE:Cholesterol:P(4,5)IP2 (10:12:35:40:3 mol:mol) and the extracellular equivalent, composed of DOPC:DOPS:DOPE:Cholesterol:Sphingomyelin (SM) (20:5:15:40:20 mol:mol). For all experiments, the intracellular equivalent side contain 150 mM KCl while the extracellular equivalent side is composed of a solution with 150 mM of monovalent chloride salt (MCl) with varying amounts of lithium and potassium. On the right, a scheme of the of the experiment with two compartments: an intracellular one (top) and an extracellular one (bottom), separated by the asymmetric suspended membrane. The intracellular compartment contains vesicles functionalized with vSNAREs to perform fusion and α-hemolysin necessary for current measurements. The suspended membrane is functionalized with tSNAREs facing the intracellular compartment. Hence, SNAREpin assembly and fusion occurs in intracellular compartment which contains potassium buffer. The extracellular equivalent side contains buffer of variable lithium concentrations. Thus, lithium interacts with the extracellular leaflet but not with SNAREs. (C) Scheme of the energetic reaction profile for fusion without any SNAREpin is plotted in grey and displays a fusion energy barrier ∆Ea0. Upon the action of a SNAREpin, the fusion barrier is lowered by ∆∆Ea1SNAREpin (orange). In contrast, in the presence of lithium, the fusion energy barrier is increased by ∆∆EaLithium (blue). (D) Experimental measurements of transient fusion frequency (in min-1) depending on lithium concentration (in mM) in the extracellular equivalent side, plot in logarithmic scale. As lithium concentration increases, fusion frequency decreases with a sharp transition in the millimolar range. (E) Table with the values of fusion frequency in min-1 with SD (middle column) for each lithium concentration tested. The column on the right presents the fusion frequency efficiency in percent taking as reference the fusion frequency measured without lithium. (F) In presence of lithium in the extracellular equivalent side, the transition from a docked state to a fused state is harder. Lithium is represented by the red sphere binding to the lipid bilayer.

In the intracellular mimic compartment, vSUVs are diffusing in solution until encountering cognate tSNAREs and eventually docking to the suspended membrane. A vesicle, docked to the membrane by an assembling SNAREpin complex, can either fuse to the suspended membrane through complete zippering or can form additional SNAREpins by assembling available membrane tSNAREs with vSNAREs on the vesicle until fusion occurs. As SNAREpin formation is the rate limiting step in spontaneous fusion mediated by SNAREs56, the first observable events on suspended membranes are fusion events mediated by only one or two SNAREpins (Supplementary Fig. S2). Such low SNAREpin numbers do not allow the fusion pore to expand after nucleation, leading to transient pore opening followed by resealing of the pore54. SNAREpins provide energy upon zippering, reducing the fusion energy barrier and thus lowering the characteristic time of vesicle fusion. This reduction of the fusion energy barrier by SNAREpins ultimately leads to fusion pore nucleation on a shorter time scale. Consequently, the transient fusion pore opening frequency is directly correlated with the fusion energy barrier. Using our dedicated microfluidic device, we measured this opening frequency with various lithium concentrations in the extracellular equivalent side. If lithium indeed increases the fusion energy barrier, it would antagonistically act on fusion regarding SNAREpins leading to a decreased fusion frequency (Fig. 3C).

We performed experiments using the same lithium concentrations as for the stretching modulus experiments, once again supplementing with KCl to reach 150 mM total concentration in monovalent salt. In order to mimic neuronal plasma membrane composition and asymmetry, the membrane outer leaflet equivalent, exposed to lithium in these experiments, was composed of DOPC, DOPS, DOPE, cholesterol and brain sphingomyelin (20:5:15:40:20 molar percentages). The apposed leaflet, mimicking the intracellular leaflet was composed of DOPC, DOPS, DOPE, Cholesterol and P(4,5)IP2 (10:12:35:40:3 molar percentages) (Fig. 3B). By increasing lithium concentration, we observe fusion frequency sharply decreases, demonstrated by plotting fusion frequency against lithium concentration in logarithmic scale (Fig. 3D). At 1.5 mM lithium in the extracellular equivalent side, transient fusion pore opening frequency decreased by 55% and at 150 mM lithium, the frequency decreases by 85% (Fig. 3E). This demonstrates that the membrane energy barrier increase due to lithium is high enough to disturb SNAREs activity without impairing their assembly processes. The membrane composition used here reproduces the PS asymmetry characteristic in the plasma membrane. Thus, the outer leaflet contains only 5% PS. Despite this low negatively charged lipid density at the surface of the outer leaflet, 1.5 mM concentration of lithium is sufficient to drastically affect fusion efficiency. Moreover, this experiment outlines the fact that, through its binding to a membrane monolayer, lithium can affect molecular events occurring on the apposed monolayer (Fig. 3F).

Discussion

Lithium direct binding on lipid affects lipid bilayers properties

The first hints of alteration of the physico-chemical properties of membranes by lithium binding to lipids date from the initial studies on melting temperature by Hauser and Shipley almost half a century ago57. Subsequent studies have investigated the molecular details of this interaction through the lens of a physico-chemical approach, leading to a characterization of the lipid-lithium interactions lacking the connection to the mesoscopic scale of the membrane. In this study, we demonstrate that lithium stiffens the lipid bilayer even at low concentrations, affecting overall membrane reorganization and deformation processes. Using an uncatalyzed membrane fusion assay, we showed that the fusion energy barrier increases by 4.5 kBT at 1.5 mM lithium, corresponding to an 80-fold reduction in reaction speed. This membrane stiffening and drastic slowdown in membrane reorganization at therapeutic concentrations of lithium pave the way for another understanding of the mode of action of lithium. Indeed, we demonstrate here, that the molecular scale of the lipid-lithium interaction intrinsically alters membrane properties over a space scale ranging from a few nanometers for fusion to micrometers for membrane deformability. Importantly, the modifications on membrane properties take place almost instantaneously. Thus, the lithium mechanism of action described here is effective as soon as lithium is introduced into the media.

Lithium in cells

The experiments in this study illustrate the effects of lithium–lipid interactions on membranes exposed to an asymmetric lithium distribution, thereby eliminating confounding influences from lithium–protein interactions. However, in a biological context, lithium enters the cell and can directly bind to proteins, potentially interfering with their function. The inability to separate the potential effects of lithium on proteins and lipids has hindered a clear understanding of its therapeutic mechanisms across the various pathways explored in the literature. To assess the impact of lithium on SNARE-mediated fusion when lithium is present on both sides of the membrane, we performed canonical bulk assays measuring lipid and content mixing at different lithium concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S3). These experiments revealed that lithium impairs membrane fusion at concentrations as low as 1.5 mM—an effect that, at first glance, could be attributed to direct modulation of SNARE activity. However, our microfluidic setup allowed us to experimentally decouple the effects of lithium from SNARE activity, demonstrating that membrane fusion is primarily impaired through the direct interaction of lithium with lipids. More broadly, this type of experimental decoupling strategy can be used to disentangle the respective contributions of protein- and lipid-mediated effects in the therapeutic action of lithium across various cellular pathways.

In this study we simplified SNARE-mediated fusion by reproducing it in vitro. As a result, the experimental conditions may not fully capture emergent mechanisms present in more complex systems, particularly competitive interactions. In a cellular environment, lithium binding to lipid headgroups could be influenced by competition with other cations. The most abundant cations in the cell are potassium (K⁺, ~ 100 mM), magnesium (Mg2⁺, ~ 10–20 mM), and calcium (Ca2⁺). Among these, only calcium has been shown to exhibit significant affinity for lipid headgroups 31,34,36,40, as it can coordinate with up to four lipid molecules, displaying a binding behavior similar to that of lithium. However, given its low and tightly regulated intracellular concentration (∼ 0.1 µM), calcium is unlikely to act as a strong competitor for lithium binding.

Lithium as a drug

We hypothesize that rapid lithium binding to membrane bilayers constitutes the primary mechanism of the therapeutic mechanism of lithium, changing lipid bilayer properties and consequently membrane protein activity. This primary mechanism would take place without any change in lipid and membrane protein content, as it appears directly upon lithium-lipid interactions. We demonstrate in the present work that this primary mechanism is sufficient to greatly alter membrane processes like fusion. Upon modifying cell state through the primary mechanism, lithium would induce longer timescale modification of the cell without interacting directly with cellular pathways, building a bridge between lithium and the numerous apparently unrelated pathways affected by this drug. Biologically, these pathways would perform metabolic adjustments 1, changes in protein expression profiles21,22,23 or modification of the lipid membranes composition58. These alterations upon lithium intake, observed in vivo, require a longer timescale to be effective and are not constant in time24. We refer to these indirect and longer timescale effects of lithium as secondary mechanisms of action. The primary and secondary mechanisms might usually be experimentally indiscernible in cellulo when looking at a single timepoint. Experimental procedures considering the kinetics aspect of these primary and secondary effects might help to draw a more complete picture of lithium therapeutic effects on cells. Moreover, high-throughput analytical methods like transcriptomic, lipidomic and metabolomic, applied at different timepoints along lithium exposure would help get a systemic description of the therapeutic effects. Temporal observations of cells pave the way for establishing causal links between the seemingly unrelated downstream effects of lithium.

Understanding the physiopathology of BD and the mode of action of lithium constitutes a great challenge. Some global modifications of the cellular state could occur in BD and be corrected when a patient is treated with lithium. Lithium perturbs membrane properties upon interacting with them. As lipid bilayers constitute the fundamental support of many cell processes, define the cellular compartments and act as interfaces between the cell and its environment, this non-specific interaction gives lithium the ability to globally affect the cell reaction network, inducing longer timescale modifications of cell state by altering metabolism and gene expression. This primary mechanism of lithium-membrane binding would constitute sort of a perturbation allowing a slower transition from a pathological state of the cell (Fig. 4A) to a treated state of the cell (Fig. 4B). Challenging this hypothesis will require to investigate the effect of lithium-lipid binding on diverse membrane processes. In the Supplementary text, we propose cellular pathways and mechanisms of interest for future investigations.

Illustration of the lithium global effect of the cell through its direct binding to lipid bilayers. On the left representation of the pathological state and on the right the Li-treated state without considering long-term modifications of the cell. Lithium ions are represented by the red particles on the right panel. We point out processes that could be affected by this direct binding. (1) Alteration of exocytosis efficiency by increase of the fusion energy barrier. (2) Impairment of endocytosis because of the stiffening of the plasma membrane. (3) Perturbation of membrane protein distribution because of thickening and stiffening of the lipid bilayers. (4) Change of the integral membrane proteins conformational equilibrium because of the alteration of the chemical environment of proteins. (5) Alteration of membrane-protein recognition and binding processes by modification of the membrane surface physico-chemical properties. (6) Perturbation of organelles function by binding of lithium to their membrane cytosolic leaflets. We take here example of mitochondria whose function are altered in BD as well as its fission–fusion balance. (7) Modification of the vesicular trafficking along the secretory pathway due to modification of membrane rearrangement, fusion or fission kinetics.

Materials and methods

Stretching modulus measurements

GUVs were formed using the electroformation method on ITO plates59. Briefly, a stock solution of 1 mM lipid in chloroform, containing 84% DOPC, 15% DOPS and 1% 18:1 Rhod-PE was generated. Then, 20 µL of this stock solution was deposited and dried on ITO plates under vacuum for 1 h. Lipids were then rehydrated with 3 mL of 200 mM sucrose. GUV formation is performed at increasing voltage steps of 100 mV, 200 mV, 300 mV, 500 mV, 700 mV, 900 mV, 1200 mV at 10 Hz for 6 min each and then at 1400 mV at 4 Hz for at least 2 h. GUVs were subsequently stored at 4 °C overnight before use.

Micromanipulation was used to measure stretching modulus. The Micropipette diameter was around 4 µm. Prior to experiments, micropipettes were incubated for 30 min in 10% Bovine Serum Albumine (BSA) solution to prevent GUV adhesion on micropipettes surface. Then, 1 mL of buffer containing various ratios of potassium chloride and lithium chloride up to 150 mM final monovalent salt concentration in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 was introduced into a 35 mm glass bottom MatTek dish, previously coated with BSA. Additional 20 µL of GUV solution were introduced into the solution 1 h before starting measurements in order for membranes to equilibrate and settle down. During mechanical measurements, the buffer solution had a 10–20% higher osmolarity than the buffer in the lumen to ensure the manipulated GUV extended inside the micropipette upon aspiration.

Micropipette aspiration was performed using ThorLab LTS300 translation stage apparatus, with a reservoir speed of 0.25 mm/s. Micromanipulations were performed using a MP-285 micromanipulator from Sutter Instrument Company. Optical fluorescence imaging was done under a scanning confocal microscope Leica Stellaris 8 with a 20 × air objective.

Elastic modulus was measured taking the slope of the curve upon plotting membrane tension ∑ depending on membrane surface extension α.

With Σ the membrane tension in N/m, ∆P being the pressure difference between the atmospherique pressure and the applied pressure, dpip being micropipette diameter and dves the diameter of the GUV.

With the membrane surface extension α being the difference in apparent surface area upon aspiration normalized by the initial vesicle area; ∆L is the difference in length of the GUV extension in the micropipette minus the length of the extension at atmospheric pressure.

Fusion energy barrier measurements

Fusion energy barrier measurements were performed as described by François-Martin et al.52. In short, vesicles were prepared by drying lipids (Avanti Research) previously dissolved in chloroform under a stream of nitrogen in a glass vial. The lipid film is then put under vacuum for an hour and then resuspended in buffer to a total lipid concentration of 18 mM. Buffer solutions were composed of 150 mM total monovalent chloride salt and 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. Lithium concentrations of 0 mM, 1.5 mM, 7.5 mM and 15 mM were tested, the complementary potassium chloride concentration necessary being supplemented to reach the monovalent salt concentration of 150 mM. Hydrated lipid film solutions were then frozen and thawed 10 times before being extruded 21 times through a 50-nm polycarbonate filter (Avanti Research). Vesicle solutions were stored overnight at 4 °C under nitrogen gas for stabilization of the membranes before the measurements. Nonfluorescent vesicles were composed only of DOPC. Fluorescent vesicles were composed of DOPC, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (18 :1 Liss Rhod PE) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) (18:1 NBD PE) in a molar ratio of 97:1.5:1.5.

Vesicle fusion was measured by monitoring the lipid mixing between fluorescent and nonfluorescent vesicles mixed at a ratio 1:7 with a final volume of 56 µL. Fluorescence was monitored at 538 nm with an excitation wavelength of 460 nm using a transparent 96-well plate with a SpectraMax M5e plate reader. Fluorescence measurements were taken from the bottom, since the plate was covered with a lid to minimize evaporation. After measuring fluorescence dequenching kinetics, the maximum fluorescence intensity was obtained by adding 50 µL of Triton X-100 at 4% (vol/vol). The fusion dequenching curves were obtained for each lithium concentration conditions at 27 °C, 32 °C, 37 °C, 42 °C and 47 °C in order to obtain Arrhenius plots.

SUVs formed using this protocol are predominantly unilamellar as confirmed by TEM imaging52. Multilamellar vesicles (MLV) would bias, fusion efficiency quantification by lowering the apparent SUV concentrations. Since the inner layers of MLVs are not accessible for fusion with other vesicles but would contribute to the fluorescence maximum intensity used to determine fusion efficiency. Such multilamellarity could lead to an underestimation of fusion efficiency. This effect would complicate the measurement of the fusion energy barrier, although it would not affect the overall conclusions of the present study.

For the analysis, the same method as described in Francois-Martin et al.52 was used. Correction factors determined for NBD maximal fluorescence intensity, whose quantum yield changes depending on temperature and the presence of detergent, were used in order to obtain a precise measure of Ea. The control curve was subtracted from the sample curve and normalized using the corrected maximal fluorescence intensity. Dequenching curves were then converted to equivalent completed fusion cycles using the calibration curves measured in Francois-Martin et al.52 that link NBD dequenching to different NBD dilutions. The fusion speed in cycles of fusion per minute is measured fitting the initial slope of the converted curve. Plotting the variation of the fusion speed with 1/kBT gives an Arrhenius plot for which activation energy can be extracted taking the slope of the linear fit (Fig. 2C).

Suspended membrane experiment preparation

A detailed protocol for microfluidic chip fabrication can be found in Heo et al.55. In short, two molds providing the top and bottom channel of the microfluidic device connected by a cylindrical conduit with a diameter of 100 µm were printed using a Titan2 HR Kudo3D 3D-printer. After assembling the two molds, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was poured and cured at 72 °C for 1 h. Subsequently PDMS was detached from the mold and rinsed in acetone and isopropanol and cured again overnight at 72 °C. The top channel was then sealed with a PDMS slab pierced with an inlet and an outlet to complete the top channel. Another PDMS piece was attached to one side of the bottom channel and punched at 0.5 mm to obtain a bottom channel inlet. The opposite side of the bottom channel was punched as well to form the bottom channel outlet. After these steps, PDMS parts of the microfluidic chip were completed and subsequently bound to a clean glass coverslip using a plasma cleaner. After total assembly, the chip was incubated at 72 °C overnight in an oven.

The SNAREs were purified following previously described protocols60, leading to the purification of tSNAREs composed of preassembled Syntaxin1A and SNAP25 and the purification of vSNARE corresponding to VAMP2 protein. Alpha-hemolysin was purchased from Sigma Aldritch (Cat. H9395). ProteoSUVs containing tSNAREs or vSNAREs and alpha-hemolysin were formed using a comicellization protocol61. In brief, tSUVs were formed by first drying a lipid flim composed of DOPC:DOPS:DOPE:Cholesterol (10:10:35:45 mol/mol), then tSNARE (in 400:1 lipid to protein ratio) and potassium buffer (150 mM KCl, 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) were poured on the film, keeping a 1% octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (OG) concentration. The mix was vortexed for 1 h to ensure complete hydration of the film. Afterwards, the solution was diluted two times with potassium buffer to pass below the OG critical micellar concentration. The final lipid concentration was 1 mM. The solution was then dialyzed overnight with SM2 bio-bead (BioRad) to remove OG. The tSUVs formed were then purified using a density gradient medium (OptiPrep, Cat. D1556, Sigma Aldrich) along with ultracentrifugation. The same procedure was used to make vSUVs containing vSNARE and alpha-hemolysin except lipid composition was DOPC:DOPS:Cholesterol:DOPE (40:10:25:25 mol/mol), vSNARE was in 200:1 lipid to protein ratio and alpha-hemolysin was in 400:1 lipid to protein ratio.

In order to form the extracellular equivalent leaflet, lipid film containing DOPC:DOPS:DOPE:Cholesterol:Sphingomyelin (20:5:15:40:20 mol/mol) was hydrated with buffer of 150 mM monovalent chloride salt concentration, 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. Buffers contained changing concentration of LiCl (0 mM, 1.5 mM, 15 mM, 150 mM) completed to total 150 mM monovalent salt concentration using KCl. Lipid final concentration in solution being 5 mM. The lipid solution was then sonicated for 10 min with cylces of 5 s pulse/5 s pause. The intracellular equivalent leaflet was formed using the same procedure with lipid film containing DOPC:DOPS:DOPE:Cholesterol:P(4,5)IP2 (10:12:35:40:3 mol/mol). Lipid film was hydrated with potassium buffer to 5 mM final lipid concentration.

Suspended membrane formation

Using CETONI Nemesys low pressure syringe pump, 12 µL of vSUVs solution was loaded in 1 mL Injekt-F syringe. The same was done in other syringes with 3 µL of extracellular equivalent leaflet solution and 3 µL of a mix intracellular equivalent leaflet: tSUVs solution (80:20%vol), this mix gave a final lipid:tSNARE ratio of 8000:1 on the suspended membrane. Then, the microfluidic chip was filled with squalene and intracellular leaflet mimicking solution (resp. extracellular leaflet mimicking solution) was injected into the top channel (resp. bottom channel) of the chip. At this step, squalene is flushed out of the chip except for the conduit connecting the top and bottom channels, forming water/squalene interfaces at the edges of the chimney. Lipid monolayers formed at each interface. Over time, PDMS continuously absorbed squalene, progressively bringing the two leaflets together until complete zippering of the two monolayers. Membrane formation was observed using a spinning disc confocal microscope Nikon Eclipse Ti and a Heka patch clamp EPC10 patch amplifier to record capacitance. During zippering, capacitance jump step was observed and kept increasing smoothly until membrane zipped to the rim of the chimney. Once membrane zippering was completed, vSUVs were injected into the top channel at 5 nl/s. Membrane voltage was clamped to 80 mV and the current was recorded at 100 kHz in cycle of 5 s measurements with 0.5 s pause between each.

Current trace analysis

In order to detect transient fusion pore nucleation, two separate procedures were used: a rolling average over 10 points and a filtering by removing frequencies around 50 Hz (standard frequencies of alternating current in Europe) were performed. Once the two transformed current traces sets were obtained, sequences for which current was higher than 1 pA for 2 ms or higher than 0.3 pA for 5 ms were automatically detected by a homemade MatLab script. After this automated detection step, we manually analyzed the detected fusion events to verify they actually correspond to fusion pores and not small electric glitches that can occur and are characterized by positive currents flanked by unrealistic negative currents. Note that once full fusion of a vesicle occurred, we stopped analysis of the experiment as noise level increased after this kind of event. Upon full fusion, the fusion pore expand till the vesicle becomes completely integrated to the membrane. This cause the alpha-hemolysin to be permanently inserted in the suspended bilayer increasing the baseline current due to the ions going through alpha-hemolysin pores. From the identified transient fusion events we then computed the fusion frequency for each lithium conditions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Kim, Y., Santos, R., Gage, F. H. & Marchetto, M. C. Molecular mechanisms of bipolar disorder: Progress made and future challenges. Front. Cell. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2017.00030 (2017).

Carlson, S. W. & Dixon, C. E. Lithium improves dopamine neurotransmission and increases dopaminergic protein abundance in the striatum after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 35(23), 2827–2836. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2017.5509 (2018).

Butler-Munro, C., Coddington, E. J., Shirley, C. H. & Heyward, P. M. Lithium modulates cortical excitability in vitro. Brain Res. 1352, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.021 (2010).

Vosahlikova, M. et al. Effect of therapeutic concentration of lithium on live HEK293 cells; increase of Na+/K+ -ATPase, change of overall protein composition and alteration of surface layer of plasma membrane”. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA): Gen. Subjects 5, 1099–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.02.011 (2017).

Alda, M. Lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder: Pharmacology and pharmacogenetics. Mol. Psychiatry 20(6), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.4 (2015).

Vošahlíková, M., Roubalová, L., Brejchová, J., Alda, M. & Svoboda, P. Therapeutic lithium alters polar head-group region of lipid bilayer and prevents lipid peroxidation in forebrain cortex of sleep-deprived rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA): Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1866(9), 158962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.158962 (2021).

Donati, R. J., Schappi, J., Czysz, A. H., Jackson, A. & Rasenick, M. M. Differential effects of antidepressants escitalopram versus lithium on Gs alpha membrane relocalization. BMC Neurosci. 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-015-0178-y (2015).

Zanni, G. et al. Lithium accumulates in neurogenic brain regions as revealed by high resolution ion imaging. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 40726. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40726 (2017).

Soares, J. C. et al. Effects of lithium on platelet membrane phosphoinositides in bipolar disorder patients: A pilot study. Psychopharmacology 149(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002139900341 (2000).

Haimovich, A., Eliav, U. & Goldbourt, A. Determination of the lithium binding site in inositol monophosphatase, the putative target for lithium therapy, by magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134(12), 5647–5651. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja211794x (2012).

Saiardi, A. & Mudge, A. W. Lithium and fluoxetine regulate the rate of phosphoinositide synthesis in neurons: A new view of their mechanisms of action in bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 8(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0235-2 (2018).

Ryves, W. J. & Harwood, A. J. Lithium Inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280(3), 720–725. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169 (2001).

Timothy O’Brien, W. & Klein, P. S. Validating GSK3 as an in vivo target of lithium action. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37(5), 1133–1138. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0371133 (2009).

Krishnankutty, A. et al. In vivo regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β activity in neurons and brains. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 8602. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09239-5 (2017).

Snitow, M. E., Bhansali, R. S. & Klein, P. S. Lithium and therapeutic targeting of GSK-3. Cells 10(2), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10020255 (2021).

Beaulieu, J.-M. et al. Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101(14), 5099–5104. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0307921101 (2004).

Beaulieu, J.-M. et al. A β-arrestin 2 signaling complex mediates lithium action on behavior. Cell 132(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.041 (2008).

Kaidanovich-Beilin, O., Milman, A., Weizman, A., Pick, C. G. & Eldar-Finkelman, H. Rapid antidepressive-like activity of specific glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor and its effect on β-catenin in mouse hippocampus. Biol. Psychiat. 55(8), 781–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.008 (2004).

Chatterjee, D. & Beaulieu, J. M. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by lithium, a mechanism in search of specificity. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15, 1028963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2022.1028963 (2022).

Freland, L. & Beaulieu, J.-M. Inhibition of GSK3 by lithium, from single molecules to signaling networks. Front. Mol. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2012.00014 (2012).

Mertens, J. et al. Differential responses to lithium in hyperexcitable neurons from patients with bipolar disorder. Nature 527(7576), 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15526 (2015).

Akkouh, I. A. et al. Exploring lithium’s transcriptional mechanisms of action in bipolar disorder: A multi-step study. Neuropsychopharmacology 45(6), 947–955. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0556-8 (2020).

Osete, J. R. et al. Lithium increases mitochondrial respiration in iPSC-derived neural precursor cells from lithium responders. Mol. Psychiatry 26(11), 6789–6805. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01164-4 (2021).

Osete, J. R. et al. Transcriptional and functional effects of lithium in bipolar disorder iPSC-derived cortical spheroids. Mol. Psychiatry 28(7), 3033–3043. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-01944-0 (2023).

Vosahlikova, M. & Svoboda, P. Lithium: Therapeutic tool endowed with multiple beneficiary effects caused by multiple mechanisms. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 76(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.21307/ane-2017-001 (2016).

Bellivier, F. & Marie-Claire, C. Molecular signatures of lithium treatment: Current knowledge. Pharmacopsychiatry 51(05), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0650-4820 (2018).

Le, C. T. M., Houri, A., Balage, N., Smith, B. J. & Mechler, A. Interaction of small ionic species with phospholipid membranes: The role of metal coordination. Front. Mater. 5, 80. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2018.00080 (2019).

Klasczyk, B., Knecht, V., Lipowsky, R. & Dimova, R. Interactions of alkali metal chlorides with phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Langmuir 26(24), 18951–18958. https://doi.org/10.1021/la103631y (2010).

Cordomí, A., Edholm, O. & Perez, J. J. Effect of ions on a dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayer. A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B 112(5), 1397–1408. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp073897w (2008).

Kruczek, J., Chiu, S.-W., Jakobsson, E. & Pandit, S. A. Effects of lithium and other monovalent ions on palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayer. Langmuir 33(4), 1105–1115. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b04166 (2017).

Kruczek, J., Chiu, S.-W., Varma, S., Jakobsson, E. & Pandit, S. A. Interactions of monovalent and divalent cations at palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine interface. Langmuir 35(32), 10522–10532. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01275 (2019).

Roux, M. & Bloom, M. Calcium, magnesium, lithium, sodium, and potassium distributions in the headgroup region of binary membranes of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine as seen by deuterium NMR. Biochemistry 29(30), 7077–7089. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00482a019 (1990).

LópezCascales, J. J. & Garcia De La Torre, J. Effect of lithium and sodium ions on a charged membrane of dipalmitoylphosphatidylserine: A study by molecular dynamics simulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 1330(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-2736(97)00156-9 (1997).

Yang, J., Calero, C., Bonomi, M. & Martí, J. Specific ion binding at phospholipid membrane surfaces. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11(9), 4495–4499. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00540 (2015).

Mao, Y. et al. Binding competition to the POPG lipid bilayer of Ca 2+, Mg 2+, Na +, and K + in different ion mixtures and biological implication. J. Phys. Chem. B 117(3), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp310163z (2013).

Böckmann, R. A. & Grubmüller, H. Multistep binding of divalent cations to phospholipid bilayers: A molecular dynamics study. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43(8), 1021–1024. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200352784 (2004).

Melcrová, A. et al. Concurrent compression of phospholipid membranes by calcium and cholesterol. Langmuir 35(35), 11358–11368. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b00477 (2019).

Rappolt, M., Pabst, G., Amenitsch, H. & Laggner, P. Salt-induced phase separation in the liquid crystalline phase of phosphatidylcholines. Colloids Surf. A 183–185, 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-7757(01)00568-4 (2001).

Sharma, V. K. & Mamontov, E. Reduction of nanoscopic dynamics in the zwitterionic membrane by salt. J. Appl. Phys. 132(7), 074702. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0102383 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Effects of Na +, K +, and Ca 2+ on the structures of anionic lipid bilayers and biological implication. J. Phys. Chem. B 114(50), 16978–16988. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp1091569 (2010).

Vácha, R. et al. Effects of alkali cations and halide anions on the DOPC lipid membrane. J. Phys. Chem. A 113(26), 7235–7243. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp809974e (2009).

Suwalsky, M., Fierro, P., Villena, F. & Sotomayor, C. P. Effects of lithium on the human erythrocyte membrane and molecular models. Biophys. Chem. 129(1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpc.2007.05.003 (2007).

Claessens, M. M. A. E., Leermakers, F. A. M., Hoekstra, F. A. & Cohen Stuart, M. A. Opposing effects of cation binding and hydration on the bending rigidity of anionic lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 111(25), 7127–7132. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp070066h (2007).

Cevc, G. & Richardsen, H. Lipid vesicles and membrane fusion. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 38(3), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(99)00030-7 (1999).

Gu, R.-X. & De Groot, B. L. Lipid-protein interactions modulate the conformational equilibrium of a potassium channel. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 2162. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15741-8 (2020).

Tang, W., Cory, B., Lim, K.-L. & Fivaz, M. The mood stabilizer lithium slows down synaptic vesicle cycling at glutamatergic synapses. Neuromol. Med. 25(1), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12017-022-08729-8 (2023).

Briggs, K. T., Giulian, G. G., Li, G., Kao, J. P. Y. & Marino, J. P. A molecular model for lithium’s bioactive form. Biophys. J. 111(2), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2016.06.015 (2016).

Jahn, R., Cafiso, D. C. & Tamm, L. K. Mechanisms of SNARE proteins in membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-023-00668-x (2024).

Rawicz, W., Olbrich, K. C., McIntosh, T., Needham, D. & Evans, E. Effect of chain length and unsaturation on elasticity of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 79(1), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76295-3 (2000).

Needham, D. & Nunn, R. S. Elastic deformation and failure of lipid bilayer membranes containing cholesterol. Biophys. J. 58(4), 997–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82444-9 (1990).

Srinivasan, C., Minadeo, N., Geraldes, C. F. G. C. & De Freitas, D. M. Competition between Li + and Mg 2+ for red blood cell membrane phospholipids: A 31 P, 7 Li, and 6 Li nuclear magnetic resonance study. Lipids 34(11), 1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-999-0474-5 (1999).

François-Martin, C., Rothman, J. E. & Pincet, F. Low energy cost for optimal speed and control of membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114(6), 1238–1241. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1621309114 (2017).

Mion, D., Bunel, L., Heo, P. & Pincet, F. The beginning and the end of SNARE -induced membrane fusion. FEBS Open Bio 12(11), 1958–1979. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.13447 (2022).

Heo, P., Coleman, J., Fleury, J.-B., Rothman, J. E. & Pincet, F. Nascent fusion pore opening monitored at single-SNAREpin resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118(5), e2024922118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024922118 (2021).

Heo, P. et al. Highly reproducible physiological asymmetric membrane with freely diffusing embedded proteins in a 3D-printed microfluidic setup. Small 15(21), 1900725. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201900725 (2019).

Li, F. et al. Energetics and dynamics of SNAREpin folding across lipid bilayers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14(10), 890–896. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1310 (2007).

Hauser, H. & Shipley, G. G. Crystallization of phosphatidylserine bilayers induced by lithium. J. Biol. Chem. 256(22), 11377–11380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)68404-8 (1981).

Müller, C. P. et al. Brain membrane lipids in major depression and anxiety disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1851(8), 1052–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.014 (2015).

Angelova, M. I. & Dimitrov, D. S. Liposome electroformation. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 81, 303. https://doi.org/10.1039/dc9868100303 (1986).

Melia, T. J. et al. Regulation of membrane fusion by the membrane-proximal coil of the t-SNARE during zippering of SNAREpins. J. Cell Biol. 158(5), 929–940. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200112081 (2002).

Heo, P. et al. A chemical controller of SNARE-driven membrane fusion that primes vesicles for Ca 2+-triggered millisecond exocytosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(13), 4512–4521. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b13449 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Claire-François Martin for helping with the fusion energy barrier measurement assay. L. B. thanks Félix Vannier and Delphine Mion for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B. and F.P. designed the research. L.B and J.C. obtained the data. L.B and F.P. analyzed the data. V.A., P.H. and F.P. supervized the research. L.B., V.A., P.H. and F.P. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bunel, L., Adrien, V., Coleman, J. et al. Lithium fine tunes lipid membranes through phospholipid binding. Sci Rep 15, 13366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97828-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97828-0