Abstract

Various therapeutic bronchoscopy techniques, including stenting, are widely utilized in the treatment of malignant central airway obstruction (MCAO), however, little data exist on the independent clinical outcomes and prognostic factors of airway stenting on MCAO. We retrospectively analyzed 287 eligible patients with MCAO who underwent therapeutic bronchoscopy at the Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, between January 1, 2016, and May 31, 2023. The length of survival was measured in months from the date of the first bronchoscopy procedure to the date of death, or until six months post-procedure or loss to follow-up. Dyspnea was assessed using the Borg score, modified Medical Research Council (mMRC), and 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), while quality of life (QoL) was evaluated using the Short Form 6-Dimension (SF-6D) and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score. All assessments were conducted consecutively at baseline, three months, and six months following the procedure. The overall survival rate was illustrated using the Kaplan-Meier curve, and the Cox proportional hazards mode were applied to evaluate multiple prognostic factors affecting survival in both groups over a 6-month follow-up period. A total of 287 patients were analyzed, including 215 in the stent group and 72 in the non-stent group. A significant difference in lesion location was observed between the groups. Postoperative stenosis was significantly improved in the stent group, with 94.41% achieving grade I stenosis compared to 8.33% in the non-stent group (P = 0.001). The stent group also showed greater improvements in KPS, Borg scores, SF-6D, and 6MWD compared to the non-stent group (P = 0.001). Additionally, significant improvements in Borg score, mMRC, 6MWD, KPS, and SF-6D were maintained at three- and six-month follow-ups. The mean survival period was significantly longer in the stent group (5.1 months) compared to the non-stent group (4.6 months). The Cox proportional hazards model identified the type of stenosis (HR: 0.184, 95% CI: 0.047–0.968, P = 0.015) and the degree of stenosis after the procedure (HR: 0.211, 95% CI: 0.061–0.726, P = 0.014) as significant factors influencing survival outcomes. Airway stenting is a safe and effective procedure leading to significant improvements in clinical symptoms and QoL for patients with MCAO at a 6-month follow-up. The type and severity of stenosis were identified as significant prognostic factors for survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malignant central airway obstruction (MCAO) affects 20–30% of patients with primary lung cancer and in those with pulmonary metastases from other malignancies, such as esophageal or thyroid cancer. In advanced stages of cancer, less than 30% of patients survive beyond five years1. Many patients with malignant cancers involving the airway are poor candidates for surgery, and available definitive therapeutic options remain limited2. The prognosis and quality of life (QoL) for most MCAO patients are severely impacted by dyspnea and respiratory failure3.

Advancements in therapeutic bronchoscopy have introduced effective therapeutic solutions for MCAO patients, including stent placement, mechanical debulking, laser cauterization, cryotherapy, and argon-plasma coagulation4. A study has demonstrated that therapeutic bronchoscopy can improve QoL by approximately 5.8% compared to baseline5. Oviatt et al. prospectively evaluated the outcomes of interventional bronchoscopy, including stent placement for MCAO, and reported significant improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and QoL at 30, 90, and 180 days6. Additionally, greater baseline dyspnea was found to correlate with more substantial improvements in QoL, as measured by the Short Form 6-Dimension (SF-6D), a comprehensive tool for assessing health-related QoL7.

Nevertheless, most studies primarily emphasize clinical outcomes and QoL improvements associated with various therapeutic bronchoscopy techniques. Studies on the prognostic factors of therapeutic bronchoscopy including stenting for MCAO remain limited5,8,9,10,11 and are often constrained by small sample sizes12,13. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of studies specifically examining the independent impact of stenting in MCAO cohorts, an essential component of interventional bronchoscopy, and the results remain controversial9,10,14,16.

Xing et al. investigated the clinical features and long-term outcomes of MCAO patients following airway stenting, identifying the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score as the primary prognostic factor for survival, rather than the site of stent placement9. Similarly, another study demonstrated that survival after metallic airway stenting was influenced by the ECOG PS score prior to stenting and the site of stent placement, emphasizing the potential for patients to undergo radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy post-stenting10. Additionally, in patients with airway obstruction caused by primary pulmonary malignancy, Kim identified independent prognostic factors associated with survival following the first bronchoscopy intervention15. On the other contrary, airway stenting provided significant symptom palliation in both groups, as evaluated by the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale and ECOG performance status. However, compared with controls, a significant survival advantage was observed only in the intermediate performance group14. Furthermore, stenting showed no significant impact on QoL and was not recommended for patients without prior oncologic treatment16.

Besides, it should be noted that previous studies have reported complication rates in MCAO ranging from 0 to 47.4% due to differences in stent types and bronchoscopy techniques16,17. Chen et al. observed no major complications related to hybrid stenting during follow-up17. Similarly, Povedano et al. demonstrated an early complication rate of 3.4% among 320 subjects. However, late complications, primarily granulation tissue formation and recurrent infections leading to airway stenosis or stent migration, were significantly more common18.

Therefore, our study aims to evaluate the clinical outcomes and identify prognostic factors associated with stenting in patients with MCAO.

Methods

Study cohort and participants

We retrospectively analyzed 287 eligible patients with MCAO who underwent therapeutic bronchoscopy at the Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, between January 1, 2016, and May 31, 2023. Chest computed tomography (CT) was initially performed for disease diagnosis and staging. Prior to airway stent placement, flexible bronchoscopy was used to assess the characteristics and severity of airway involvement in all patients, allowing for the selection of the appropriate type and size of airway stent. MCAO was defined as ≥ 50% occlusion of the cross-sectional area of the central airway based on CT or bronchoscopy findings19. Disease staging was assessed at the time of diagnosis. Patient outcomes were evaluated, and follow-up data were collected six months after tracheobronchial stent implantation.

All patients underwent routine bronchoscopy therapy including mechanical debulking, laser therapy, or argon-plasma coagulation, based on the degree of airway stenosis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients with airway stenosis exceeding 50% of the inner luminal diameter, resulting in significant dyspnea or pneumonia; (II) patients with stenosis of the carina involving the trachea and one or both main bronchi; (III) patients with inoperable advanced malignant stenosis. Patients were excluded if other medical conditions were identified as the cause of symptoms such as dyspnea or hemoptysis, if they had irreversible bleeding diathesis, or if the assessing interventional pulmonologist determined that the patient was in severe cardiopulmonary compromise and unable to tolerate bronchoscopy.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Zzsyy KYB2016168). All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Demographic data, histologic subtypes of malignancy, bronchoscopy findings (including type of obstruction and severity of stenosis), previous treatments, and details of bronchoscopy procedures were recorded.

Assessment of airway stenosis type and quality of life

According to previous literature, airway stenosis is classified into three types: intraluminal, extraluminal, and mixed. The degree of stenosis is determined by the percentage reduction in the cross-sectional area: Grade I, ≤ 50% luminal stenosis; Grade II, 51–70% luminal stenosis; Grade III, 71–99% luminal stenosis; and Grade IV, complete obstruction with no lumen20. Dyspnea was assessed using the Borg score, mMRC, and 6MWD, while QoL was evaluated using the SF-6D and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)21,22. All assessments were conducted consecutively at baseline, three months, and six months following the procedure.

Therapeutic bronchoscopy procedures

Therapeutic bronchoscopy was performed according to standard techniques23. In a majority of cases, a flexible bronchoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to evaluate the features of the stenosis. For some patients, after induction of general anesthesia and intubation with a rigid bronchoscope tube (Bryan Co., Woburn, MA, USA or Karl-Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany), intraluminal mass was removed mechanically using rigid bronchoscope tubes. In cases of extrinsic compression or a high likelihood of rapid tumor ingrowth, a stent was placed to maintain airway patency24.

Anaesthetic and airway management

Prior to interventional procedures with bronchoscopy, careful endoscopic assessment of the airway was carried out to verify the site and extent of the lesions. Anesthesia induction was initiated with target-controlled infusion (TCI) of propofol at a plasma target concentration of 2–3 µg/ml, followed by sequential intravenous administration of fentanyl at 3 µg/kg. Anesthesia maintenance was achieved using TCI of propofol at a plasma target concentration of 2–4 µg/ml and continuous intravenous infusion of remifentanil at 0.1–0.2 µg kg−1 min−1. Vasoactive drugs were administered as needed. Muscle relaxation is achieved with rocuronium 50 mg as needed. Airway management is adjusted based on the location of the stenosis: a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is used for upper tracheal or subglottic stenosis, while endotracheal intubation or rigid bronchoscopy is preferred for lower tracheal lesions. For LMA or endotracheal intubation, conventional mechanical ventilation is employed, whereas rigid bronchoscopy is performed with 100% oxygen using high-frequency jet ventilation (frequency: 42 cycles/min), maintaining PETCO2 at 35–45 mmHg. Continuous monitoring includes electrocardiograms, invasive arterial blood pressure, SpO2, bispectral index (40–65), and transcutaneous CO2/O2. Arterial blood gas analysis is performed every 30 min for electrolyte/acid-base correction. Critical strategies include: pre-induction lidocaine nebulization, intravenous steroids (methylprednisolone 40 mg) to prevent edema, and protocolized responses to hypoxemia/CO2 retention (procedure pause + intensified ventilation). Postoperative airway management involved manually ventilating patients using a handheld face mask, laryngeal mask airway (LMA), or endotracheal tube, depending on the level of muscle relaxation and the need for ventilatory positive airway pressure or driving pressure, until sufficient vigilance and spontaneous breathing were achieved25,26,27.

Management of the risk of ventilatory failure during induction of general anaesthesia

A thorough preoperative assessment of airway obstruction, pulmonary comorbidities, and the likelihood of a difficult airway is essential, along with adequate preparation of advanced airway management equipment, including video laryngoscopes, fiberoptic or rigid bronchoscopes. Pre-induction preparation includes effective preoxygenation with 100% O2 or high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO), and ensuring the availability of ventilation and intubation devices. During induction, strategies such as rapid sequence induction and the use of rigid bronchoscopy, conventional mechanical ventilation or high-frequency jet ventilation ensure effective oxygenation alongside continuous monitoring of SpO2, EtCO2, and airway pressures. Emergency management protocols must address hypoxia with measures like HFNO, reintubation, resolve obstructions through rigid bronchoscopy or emergency cricothyroidotomy, and treat bronchospasm with anaesthetic deepening and bronchodilators.

Definition of complications

Procedure-related complications were categorized as “early” (occurring within 48 h of the intervention) or “late” (occurring after 48 h). Respiratory distress was defined as a decrease in oxygen saturation or worsening dyspnea requiring additional oxygen support within 48 h after stenting. Excessive bleeding was defined as bleeding severe enough to require a blood transfusion or escalated medical care24.

Follow up

All patients were followed up for a total of six months after first interventional bronchoscopy. A routine bronchoscopy was performed one week after the procedure to assess the status of the stent and remove any tenacious secretions. Subsequent bronchoscopies were scheduled at the physician’s discretion, based on clinical necessity. Following the initial stenting, additional bronchoscopy interventions, including APC, laser therapy, and cryotherapy, were performed as needed to maintain airway patency in cases of recurrent CAO. Follow-up visits were conducted every three months unless there were emergent symptoms requiring immediate medical intervention. At each follow-up visit, symptom and QoL was evaluated and chest contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed.

Study outcomes

The length of survival was measured in months from the date of the first bronchoscopy procedure to the date of death, or until six months post-procedure or loss to follow-up. The primary outcome of the study was defined as death or loss to follow-up. As long as any of these events was achieved, we identified that the outcome of the study is reached. The length of survival was measured in months from the date of the first bronchoscopy procedure to the date of death, or until six months post-procedure or loss to follow-up.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Patient characteristics were analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed numerical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and other numerical data were presented as median (interquartile range). Comparisons of categorical data between the two groups were made by chi-square or Fisher’s exact probability test. Continuous variables were compared by two-tailed t test. Mann-Whitney U test was applied where required. Pre‑ and post‑procedure comparisons were done using Friedman test. The overall survival rate was illustrated using the Kaplan-Meier curve, and the Cox proportional hazards mode were applied to evaluate multiple prognostic factors affecting survival in both groups over a 6-month follow-up period. Results of potential predictors were presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Differences of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

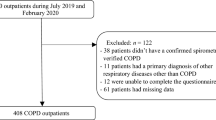

A total of 422 patients participated in the project. According to the exclusion criteria, 135 patients were excluded, and 287 patients were included in the study finally, with 215 patients in the stent group and 72 in the non-stent group. The mean age was 64.47 ± 13.15 years in the stent group and 66.06 ± 14.46 years in non-stent group (P = 0.156). Male patients predominated in both groups (73.02% vs.76.39%, P = 0.574). There were no significant differences regarding comorbidities, chronic lung disease was the most prevalent condition in both groups (47.44% vs. 34.72%), followed by chronic liver disease and diabetes (P = 0.589). The pathological diagnosis distribution between groups was similar (P = 0.904), and metastatic malignancy was the most common, predominantly from esophageal cancer. The majority of patients presented with mixed-type stenosis (66.51% vs. 61.11%). The types of stenosis, tumor staging and previous treatment modalities showed no significant difference. And the degree of stenosis (grade II, III, IV) was comparable between the groups (P = 0.617).

The significant difference between groups was observed in lesion location (P = 0.001). The stent group showed a higher proportion of upper tracheal (12.56%), while the non-stent group had more frequent involvement of the right middle bronchus (25.00% vs. 0.93%) (Table 1).

Treatment modalities and clinical outcomes

All patients undergoing bronchoscopic interventions are managed under general anaesthesia. In our study, a total of 47 patients undergoing stent placement were managed with a combination of a rigid bronchoscope and a flexible bronchoscope, while 168 patients underwent procedures using only a flexible bronchoscope. Among these 168 patients, 20 patients were managed with a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), and 148 patients were managed with endotracheal intubation, resulting in a proportion of 68.84% for endotracheal intubation. In the non-stent group, 21 patients were managed with a combination of a rigid bronchoscope and a flexible bronchoscope, while 51 patients underwent endotracheal intubation under flexible bronchoscopy, with the proportion of endotracheal intubation being 70.83%. The degree of stenosis after the operation was significantly better in the stent group, with 94.41% achieving grade I compared to only 8.33% in the non-stent group (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference in KPS scores, mMRC, Borg scores, SF-6D and 6WMD between the stent and non-stent groups before the procedure. However, the stent group showed a significant improvement in KPS, Borg scores, SF-6D and 6WMD compared to the non-stent group (P = 0.001) (Table 2). Furthermore, significant improvements in Borg score, mMRC, 6MWD, KPS score and SF-6D were observed at follow-up three and six months later (Table 3). The choice of bronchoscopy technique did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.207), with the majority of procedures performed using flexible bronchoscopy. In the stent group, the types of stents used included covered metallic straight (89.3%), covered metallic Y (5.58%), and silicone stents (5.12%).

Early complications such as respiratory distress and bleeding were comparable between groups (P = 0.534). Although late complications like increased secretion were more common in the non-stent group (45.83% vs. 30.70%), this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.111) (Table 2). No procedure‑related mortality occurred in our study (Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses and Cox proportional hazards mode

Patients with stents (5.1 months) showed significantly higher overall survival rates than those without stents (4.6 months) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1). Among patients receiving stents, those with extraluminal and mixed stenosis had the more favorable prognosis compared to intraluminal type (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2), and covered metallic straight stents were associated with the best survival outcomes among stent types (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3). In the non-stent group, a lower degree of post-operative stenosis was significantly linked to improved survival, particularly between patients with grade I and II stenosis (P < 0.01). (Fig. 4)

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival for patients without airway stenting, categorized by the degree of post-operative stenosis. The length of survival was measured in months from the date of first bronchoscopic procedure to the date of death, or until six months post-procedure or loss to follow-up.

The Cox proportional hazards model revealed that both the type of stenosis and the degree of post-operative stenosis significantly influenced survival outcomes. The hazard ratio (HR) for the type of stenosis was 0.184 (95% CI: 0.047–0.968, P = 0.015), while the HR for the degree of post-operative stenosis was 0.211 (95% CI: 0.061–0.726, P = 0.014) (Table 4).

Discussion

Therapeutic bronchoscopy is recognized as a safe and effective treatment for MCAO, which causes dyspnea, reduced quality of life, and decreased life expectancy15. Our study found significant improvements in mMRC, Borg score, KPS score, 6MWD, and SF-6D at both 3 and 6 months following the procedure, especially in the stent group. Patients with stents had significantly higher survival rates than controls. Among patients receiving stents, those with extraluminal stenosis and covered metallic straight stents were linked to better survival outcomes compared to controls. Besides, in the non-stent group, the degree of post-operative stenosis was also significantly associated with improved survival outcomes.

Indeed, most studies have demonstrated that therapeutic bronchoscopy could provide immediate relief and survival improvement in MCAO using a combination of bronchoscopy techniques5,8,9,10,11,12. A prospective study reported that the technical success rate of therapeutic bronchoscopy in MCAO was 90%. They found that the higher basic Borg score was associated with the more significant improvement of postoperative dyspnea and QoL5. Oviat et al. described that 6MWD, FEV1 and FVC values in lung function, dyspnea and QoL were significantly improved 30 days after airway intervention therapy6. It is worth noting that the incidence of complications associated with therapeutic bronchoscopy has attracted more attention. A study has shown that the incidence of complications following stent placement ranges from 0% to18%28. Ost et al. conducted a multicenter study on patients undergoing therapeutic bronchoscopy for MCAO, reporting an overall complication rate of 3.9%. Identified risk factors for complications included emergent procedures, higher American Society of Anesthesiologists scores, therapeutic bronchoscopy and the use of moderate sedation. Notably, 30-day mortality rates were observed to increase after stent placement19, potentially due to severe infections secondary to stenting. We found no serious complications following stent placement, and the overall incidence of complications was comparable between groups, which was in consistent with previous research29. These variations in complication rates across different periods highlight the importance of carefully balancing the risks and benefits of stenting.

Although the impact of therapeutic bronchoscopy on survival and QoL has been extensively studied5,8,9,10,11,30, supporting our findings. And tracheobronchial stents are widely used in patients with MCAO, However, there is limited literature on the independent effects of stent placement on clinical outcomes and prognosis9,10, and the available evidence remains controversial12,14,16,31. Saji et al. demonstrated a survival benefit associated with stenting. While an aggressive stenting strategy is justified to alleviate symptoms and enhance QoL, their study concluded that airway stenting itself does not directly contribute to a survival benefit31. Similarly, Dutau et al. suggested that stenting does not significantly impact QoL and is primarily recommended for patients who experience failure of first-line chemotherapy. Importantly, stent placement is not advised for patients who have not undergone prior oncologic treatment16. Airway stenting provided significant symptom relief evaluated by the MRC dyspnea scale and ECOG performance status in both groups. Compared to historical controls, a significant survival advantage was observed only in patients with intermediate performance status14. Also, Kim identified independent prognostic factors for survival following the first bronchoscopy intervention in patients with airway obstruction caused by advanced lung or esophageal cancer. Treatment-naïve status, an intact proximal airway and the availability of additional post-procedural treatments contributed to good prognosis. However, stenting was found to have no significant impact on overall survival rates12. Similarly, while stenting followed by adjuvant therapy resulted in a four-month increase in median survival time and improved QoL, stenting itself did not contribute to survival benefit31, which contrasts with our findings. Different from other articles focusing solely on stent cohort populations, we included follow-up, dynamic monitoring in both stent and non-stent populations at the same period, highlighting the independent impact of stenting based on other therapeutic bronchoscopy approaches.

Compared to previous studies31,32, our findings indicate a difference in survival time following stent treatment. In their study, the mean survival period after stenting was only 85.2 days which was significantly shorter than that observed in our study. And performance status (PS) prior to airway stenting was identified as a potential predictor of prognosis following the procedure. Notably, this study exclusively included cases of severe central airway obstruction caused by advanced cancer treated with metal airway stenting32. Hisashi et al. demonstrated that patients who received follow-up radiotherapy or chemotherapy after stent placement had better survival outcomes compared to those who did not. The treatment status and adjuvant treatment after airway stenting may be associated with survival outcome13. Stenting for airway stenosis may improve prognosis in patients with lung or thyroid cancer, especially if patients with lung cancer undergo additional treatments after stenting, although airway stenting for patients with esophageal cancer was palliative. The primary differences may be attributed to variations in population-based performance status (PS) scores and comorbidities. Although we did not show that KPS score or age was a prognostic factor for stent implantation, there were still significant differences in KPS score, Borg, and SF-6D scores between both groups after treatment. And 70% of those patients presenting with ECOG 3 to 4 scores could not receive systemic therapies would be contraindicated due to poor baseline ECOG score29. And airway stenting for advanced cancer may be more effective for patients in good general condition than controls32. We hypothesized that bronchial interventions including stenting may enhance patient tolerance, allowing them to receive additional therapeutic options to ultimately improving their prognosis.

A study has specifically identified prognostic factors influencing the survival of patients with advanced lung or esophageal cancer undergoing bronchoscopy intervention. Improved survival was observed in patients with certain favorable conditions, including treatment-naïve status, an intact proximal airway, and the availability of additional post-procedural treatments12. Meanwhile, poor survival was associated with factors such as extensive lesions, extrinsic or mixed lesions following bronchoscopy intervention15. Stenting maintained airway patency in some patients with extrinsic compression, meanwhile, stent placement was identified as one of the risk factors of post-intervention complications and poorer survival33. In contrast to previous findings, we suggested that patients with extraluminal and mixed-type stenosis exhibited the more favorable prognosis. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that the previous study primarily focused on lung cancer patients, where most cases involved internal or mixed lesions. This may also be related to the relatively large proportion of mixed-type patients in this study. Future research will require the collection of more data and matched verification to confirm these findings. Regarding different types of airway obstruction, airway patency in cases of single lesions could often be maintained through stenting or other treatment modalities until adjuvant therapies became available. In cases of extensive lesions, MCAO may recur before adjuvant treatment can commence15. Additionally, mixed lesions, which often require multimodal therapy to maintain airway patency, may increase the risk of procedure-related complications and mortality19. We emphasized the importance of regular monitoring for the timely diagnosis of complications in cancer survivors and recommended routine bronchoscopy within 48–72 h after stent placement.

Consistent with Sehgal34, we highlighted that the degree of airway stenosis was a crucial prognostic factor in both groups, particularly for assessing stenosis following intervention. In cases of extensive lesions, airway patency can be maintained through stenting until adjuvant treatments become available15. Notably, Lachkar et al. reported significantly higher rates of stent failure in silicone stents compared to self-expanding metal stents, based on a comparative analysis of silicone Y-shaped and self-expanding metallic Y-shaped stents35. We believe this may be attributed to factors such as stent displacement, the supporting force of metal stent, airway secretions, degree of stenosis and patient’s underlying condition. For certain patients with MCAO, such as those with thyroid cancer, the technical success rate may be associated with the less invasive nature of airway involvement, and stenting could potentially improve prognosis. The efficacy of airway stenting depends on proper patient selection and the anatomic location of the obstruction. Therefore, careful evaluation of the risks and benefits is essential when considering stenting for each patient.

Limitations

Certain limitations of our study must be acknowledged. Firstly, this was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution. Also, we did not document the length of the stenotic segment. The significant heterogeneity in the classification of airway involvement, patient and stent selection and preoperative inflammatory states may have led to some bias. Nevertheless, we performed a dynamic evaluation of QoL and symptomatic changes after stenting to mitigate this to some extent. Secondly, due to ethical considerations, conducting a prospective, randomized controlled study is challenging. Also, the proportion of patients in the non-stent group and non-central airway group was higher, full matching could not be achieved. Thirdly, due to the study design, we were unable to evaluate the improvement and survival benefits over a longer follow-up period. However, it is worth noting that our median survival is comparable to that reported previously31,32.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated that airway stenting is both safe and effective, leading to significant improvements in clinical symptoms and QoL for patients with MCAO at a 6-month follow-up. Additionally, the type and severity of stenosis were identified as significant prognostic factors for survival in stenting group. Further research with more robust study designs and larger sample sizes is needed to better define the value of stenting in the management of MCAO.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MCAO:

-

Malignant central airway obstruction

- 6MWD:

-

6-minute walk distance

- mMRC:

-

Modified Medical Research Council

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky Performance Score

- SF-6D:

-

Short form 6-dimension

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- PS:

-

Performance status

References

Cavaliere, S., Venuta, F., Foccoli, P., Toninelli, C. & La Face, B. Endoscopic treatment of malignant airway obstructions in 2,008 patients. Chest 110, 1536–1542 (1996).

Iyoda, A. et al. Contributions of airway stent for Long-term outcome in patients with malignant central airway stenosis or obstruction. J. Bronchol. Interv. Pulmonol. 28, 228–234 (2021).

Ernst, A., Feller-Kopman, D., Becker, H. D. & Mehta, A. C. Central airway obstruction. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 1278–1297 (2004).

Ost, D. E. et al. Therapeutic bronchoscopy for malignant central airway obstruction: Success rates and impact on dyspnea and quality of life. Chest 147, 1282–1298 (2015).

Ong, P. et al. Long-term quality-adjusted survival following therapeutic bronchoscopy for malignant central airway obstruction. Thorax 74, 141–156 (2019).

Oviatt, P. L., Stather, D. R., Michaud, G., Maceachern, P. & Tremblay, A. Exercise capacity, lung function, and quality of life after interventional bronchoscopy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6, 38–42 (2011).

Olfson, M., Wall, M., Liu, S-M., Schoenbaum, M. & Blanco, C. Declining Health-Related quality of life in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 54, 325–333 (2018).

Ernst, A., Simoff, M., Ost, D., Goldman, Y. & Herth, F. J. F. Prospective risk-adjusted morbidity and mortality outcome analysis after therapeutic bronchoscopic procedures: Results of a multi-institutional outcomes database. Chest 134, 514–519 (2008).

Xing, Y., Lv, X., Zeng, D., Jiang, J. & Zhang, P-Y. Clinical study of airway stent implantation in the treatment of patients with malignant central airway obstruction. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2022, 1–8 (2022).

Qian, H-W. et al. Survival and prognostic factors for patients with malignant central airway obstruction following airway metallic stent placement. J. Thorac. Dis. 13, 39–49 (2021).

Jeon, K. et al. Rigid bronchoscopic intervention in patients with respiratory failure caused by malignant central airway obstruction. J. Thorac. Oncol. 1, 319–323 (2006).

Kim, H. et al. Prognostic factors for bronchoscopic intervention in advanced lung or esophageal cancer patients with malignant airway obstruction. Ann. Thorac. Med. 8 (2013).

Leelayuwatanakul, N. et al. The prognostic predictors of airway stenting in malignant airway involvement from esophageal carcinoma. J. Bronchol. Interv. Pulmonol. 30, 277–284 (2023).

Razi, S. S. et al. Timely airway stenting improves survival in patients with malignant central airway obstruction. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 90, 1088–1093 (2010).

Kim, B-G., Shin, B., Chang, B., Kim, H. & Jeong, B-H. Prognostic factors for survival after bronchoscopic intervention in patients with airway obstruction due to primary pulmonary malignancy. BMC Pulm. Med. 20, 54 (2020).

Dutau, H. et al. Impact of silicone stent placement in symptomatic airway obstruction due to Non-Small cell lung Cancer—A French multicenter randomized controlled study: The SPOC trial. Respiration 99, 344–352 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Hybrid stenting with silicone Y stents and metallic stents in the management of severe malignant airway stenosis and fistulas. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 2218–2228 (2021).

Cosano Povedano, A., Muñoz Cabrera, L., Cosano Povedano, F. J., Rubio Sánchez, J., Pascual Martínez, N., & Escribano Dueñas, A. Endoscopic treatment of central airway stenosis: Five years’ experience. Arch. Bronconeumol. 41, 322–327 (2005).

Ost, D. E. et al. 1Complications following therapeutic bronchoscopy for malignant central airway obstruction: Results of the aquire registry. Chest 148, 450–471 (2015).

Myer III, C. M., O’Connor, D. M., Cotton, R. T. & rd, Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 103, 319–323 (1994).

Huret, B. et al. Treatment of malignant central airways obstruction by rigid bronchoscopy. Rev. Mal. Respir. 32, 477–484 (2015).

Brazier, J., Roberts, J. & Deverill, M. The Estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J. Health Econ. 21, 271–292 (2002).

Kim, H. Stenting therapy for stenosing airway disease. Respirology 3, 221–228 (1998).

Shin, B., Chang, B., Kim, H. & Jeong, B-H. Interventional bronchoscopy in malignant central airway obstruction by extra-pulmonary malignancy. BMC Pulm. Med. 18, 46 (2018).

Schulze, A. B. et al. Central airway obstruction treatment with self-expanding covered Y-carina nitinol stents: A single center retrospective analysis. Thorac. Cancer 13, 1040–1049 (2022).

Kızılgöz, D., Aktaş, Z., Yılmaz, A., Öztürk, A. & Seğmen, F. Comparison of two new techniques for the management of malignant central airway obstruction: Argon plasma coagulation with mechanical tumor resection versus cryorecanalization. Surg. Endosc. 32, 1879–1884 (2017).

Matsuda, N. et al. Perioperative management for placement of tracheobronchial stents. J. Anesth. 20, 113–117 (2006).

Tanigawa, N., Sawada, S., Okuda, Y., Kobayashi, M. & Mishima, K. Symptomatic improvement in dyspnea following tracheobronchial metallic stenting for malignant airway obstruction. Acta Radiol. 41, 425–428 (2015).

Lee, E. Y. C., McWilliams, A. M. & Salamonsen, M. R. Therapeutic rigid bronchoscopy intervention for malignant central airway obstruction improves performance status to allow systemic treatment. J. Bronchol. Interv. Pulmonol. 29, 93–98 (2022).

Stratakos, G. et al. Survival and quality of life benefit after endoscopic management of malignant central airway obstruction. J. Cancer 7, 794–802 (2016).

Saji, H. et al. Outcomes of airway stenting for advanced lung cancer with central airway obstruction. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 11, 425–428 (2010).

Lee, J. W. et al. Indications of airway stenting for severe central airway obstruction due to advanced cancer. PLoS One 12, e0179795 (2017).

Li, Y., Ren, J., Chen, J. & Han, X. Letter about outcome differences between recanalized malignant central airway obstruction from endoluminal disease versus extrinsic compression. Lasers Med. Sci. 34, 1723–1723 (2019).

Agarwal, R. et al. Placement of tracheobronchial silicone Y-stents: Multicenter experience and systematic review of the literature. Lung India 34, 311–317 (2017).

Lachkar, S. et al. Self-expanding metallic Y-stent compared to silicone Y-stent for malignant lesions of the main carina: a single center retrospective study. Respir Med. Res. 78, 100767 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all staffs of Department of Intensive Critical Care Unit and Department of Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in the analysis of data.

Funding

This work was supported by grant 2023J01122413 for Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, grant ZZ2023J19 for Natural Science Foundation of Zhangzhou, grant 2017XQ1116 for Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University, grant 2020J01122220 Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, grant 2017-1-87 for Youth Research Fund from Fujian Provincial Health Bureau and grants PDA202203 for Grade A for scientific research of Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.J.C., Z.L.J., L.L. and L.H. designed and analyzed the data and contributed to the manuscript preparation. W.T.Z., and W.Z. contributed to the design of the study and analyzed the data. Y.Y.M. contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Q.J.C., Z.L.J. and W.Z. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Prior ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zhangzhou affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Zzsyy KYB2016168). All patients provided informed written consent before the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, J.C., Zhi, L.J., Wu, Z. et al. Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes of stenting on malignant central airway obstruction. Sci Rep 15, 13695 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97850-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97850-2