Abstract

This study aimed to identify the differences in masseteric activity during maximum mouth opening among healthy volunteers, patients with limited mouth opening (LMO) and myofascial pain, and patients with LMO and disc displacement. Thirty-seven patients with temporomandibular disorders and LMO (< 40 mm) and 27 healthy volunteers participated in this study. Patients were categorized into three groups based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and clinical symptoms: disc displacement (DD), disc displacement with myofascial pain (DD + M), and myofascial pain (M). The DD group included pain-free disc patients with displacement patients, excluding those with myofascial pain or arthralgia. After a five-minute relaxation period, the participants were instructed to perform maximum opening (Omax) and maintain the Omax position for five seconds, and this was repeated three times. Subsequently, the participants were asked to perform maximum voluntary clenching for five seconds, which was repeated twice. At rest, no significant masseter potential differences were observed among the DD, DD + M, M, and healthy groups (p > .05). However, during Omax, the DD + M and M groups exhibited significantly higher masseteric potential than the healthy and DD groups (p < .001). Furthermore, the masseteric potential during Omax correlated with self-reported pain levels on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Overall, there are distinct differences in masseteric activity levels between patients with LMO and with or without myofascial pain or disc displacement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) represent the most prevalent type of musculoskeletal dysfunction, with symptoms including myofascial pain, clicking sounds in the temporomandibular joints (TMJ), and alteration of jaw motion1,2,3. Among these characteristics, limited jaw movement, also termed limited mouth opening (LMO), significantly decreases the quality of life of patients, leading them to seek medical assistance1,2,3. The extent of mouth opening is an essential clinical index for evaluating mandibular function4. Generally, in healthy adults without myofascial pain, joint dysfunction, or congenital malformations, the inter-incisor distance during unassisted maximum opening (Omax) is more than 40 mm, although the mouth opening range varies with sex, age, body size, and race5.

The causes of LMO can be arthrogenic and/or myogenic1,6,7. Arthrogenic dysfunction includes disc displacement, osteoarthritis, degenerative joint disease, inflammatory arthritis, joint adhesion, and ankylosis8. Disc displacement is the most common arthrogenic condition, characterized by the anterior displacement of the disc when the mouth is closed2,6. It can be further classified into anterior disc displacement with reduction (ADDwR) and anterior disc displacement without reduction (ADDw/oR)9. Myogenic dysfunction, which is closely related to the masticatory muscles, involves myofascial pain (MFP), tendonitis, and spasms1,6,10. Myofascial pain presents as tenderness and persistent muscle pain that arises from trigger points, significantly decreasing TMJ function11.

To assess the morphological changes in the TMJ and location of the disc, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination has become an indispensable tool12,13. It provides high specificity and accuracy for the diagnosis of arthrogenic dysfunction. Surface electromyography (sEMG) is used to evaluate muscle activity during functional movement. It is a valuable tool that is non-invasive and easily accepted by patients14,15. In particular, sEMG simultaneously collects signals from different motor units of the target muscle. After amplification and filtering, the oscilloscope shows the raw signal as an overlap of single motor unit activity, making muscle movements visible and quantifiable16.

Recently, researchers have attempted to determine the correlation between pain and muscle dysfunction. Some studies have reported experimental noxious stimulation of the masticatory muscles and significant changes in muscle activity and jaw movement velocity during mouth opening and chewing tasks17,18,19. Other studies have indicated that masticatory muscle activity is higher in children with pain-related TMD than in children with pain-free TMD20. Patients with TMD show lower maximum voluntary clenching (MVC) and higher masticatory muscle activity during chewing21. Masticatory muscle hyperactivity responds to the threat of injury and the sensation of pain, and is controlled by the central nervous system22.

Pain is a major factor affecting alternative muscle movements23. However, whether this hyperactivity of the masticatory muscles leads to limited mouth movement is still under debate, and the relationship between pain level and hyperactivity of the masticatory muscles is unclear. Some studies have reported that experimentally induced temporalis muscle pain may alter muscle activity during various tasks; however, no association with the jaw displacement magnitude has been observed17,24. In addition, the masticatory muscle function in patients with TMD who suffer from LMO accompanied by both disc displacement and myofascial pain has not yet been reported.

This study aimed to compare masseteric EMG activity during Omax among four groups: healthy volunteers, patients with LMO and disc displacement, patients with LMO and myofascial pain, and patients with LMO presenting both disc displacement and myofascial pain. The null hypothesis posited no significant inter-group differences in masseteric EMG activity during Omax and no association between muscle activity and pain level.

Materials and methods

Subjects

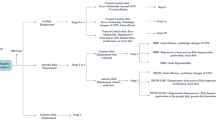

Subjects were recruited among 124 outpatients with TMD at the Department of Fixed Prosthodontics of Osaka University Dental Hospital, between March 2020 and October 2021. The inclusion criteria involved patients with TMD and LMO (Omax < 40 mm). The exclusion criteria included LMO caused by ankylosis, trauma, hypophrenia, or physical disease (Fig. 1).

Based on these criteria, 37 patients with TMD and LMO (degree of mouth opening: 28.3 ± 6.3 mm, age: 46.9 ± 18.5 years, 34 females and three males) and 27 healthy volunteers (degree of mouth opening: 49.9 ± 6.7 mm, age: 26.0 ± 2.7 years, 15 females and 12 males) participated in this study. All the patients and healthy volunteers were assessed using the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD). Additionally, all the patients underwent MRI examinations, and, at the initial visit, the experiment in this study (including EMG recordings) was performed prior to treatment.

The thirty-seven patients with TMD and LMO were categorized into three groups: disc displacement (DD) group (n = 6), myofascial pain (M) group (n = 11), and disc displacement with myofascial pain (DD + M) group (n = 20). The bilateral masseter muscles of each patient were measured, resulting in data regarding 74 muscles in the TMD group and 54 muscles in the control group for statistical analysis. The healthy volunteers exhibited no symptoms of TMDs. The baseline data are presented in Table 1.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of good practice and performed with the approval of the Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry and the Ethics Review Committee of the Dental Hospital (R1-E25).

Methods

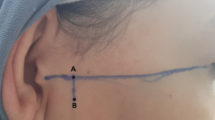

sEMG recording and jaw tasks

The participants sat in a natural and relaxed position during the recording. The skin over the masseter muscle was cleaned and prepared using a gel to reduce impedance. Paired pre-amplified surface electrodes (Mega Electronics, Finland) were positioned at the midline of the bilateral masseter muscles and at the anterior belly of the right digastric muscle. These electrodes were securely attached to the skin using medically pressurized tape to prevent movement during Omax. Muscle activity was recorded using the ME6000 Biomonitor (Mega Electronics, Finland), and sEMG measurements were consistently conducted throughout all experimental procedures, including practice.

The sEMG signals were amplified (gain: 305 times) using low-pass filtering (8–500 Hz). The standard mode rejection ratio was 110 dB and the input noise was < 1.6 µV. The raw muscle signals were analog-to-digital (A/D) converted (1000 Hz, 14 bits resolution) and transferred to the MegaWin software (Mega Electronics, Finland), which can monitor the raw signal of muscles in real time. Before the experiment, the examiner explained how to perform the Omax and passive stretch training. Participants strictly followed the instructions to open and close their mouths and practiced three times before each task.

This experiment consisted of three tasks:

Rest

Relax and keep teeth untouched for five minutes; calculate the last 30 s as the rest potential.

Omax

Perform unassisted mouth opening slowly and maintain the maximum mouth opening position for five seconds regardless of whether the participants feel pain or discomfort; repeat this process three times.

MVC

Clench the molar teeth with maximum power for five seconds; repeat this process twice.

A vernier caliper was used to measure the degree of opening during Omax. The subjective pain level was recorded using a 100 mm pain visual analog scale (VAS) after Omax. Before each task, the patients rested for five minutes to avoid muscle fatigue.

Assessment of myofascial pain and disc displacement with or without reduction

The diagnostic method for myofascial pain involved palpating the bilateral masseter and temporalis muscles with a force of 1 kg which was maintained for two seconds25. A palpeter (Sunstar; Butler, UK) was employed to calibrate the appropriate palpation force. Three TMD specialists certified by the Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joint conducted random assessments of the patients, followed by the DC/TMD clinical examination.

Intra-articular disorders were examined using an MRI scanner (Signal HDxt 1.5T; GE Healthcare) during both mouth opening and closing. After the MRI scans, the maxillofacial radiologists reported the disc location and condylar shape. ADDwR was identified when the disc returned to its normal position during mouth opening, whereas continuous anterior displacement was defined as ADDw/oR26. Patients with ADDwR or ADDw/oR were grouped into the DD group, and the DD + M category included those with anterior disc displacement and myofascial pain.

Data analysis

Digastric muscle activity marked the onset and end of mouth opening. Raw EMG data were rectified (absolute mean value) and smoothed (mean value of 100 data points in a 0.1-second frame width). The average and maximum potentials of the bilateral masseter muscles during each opening phase were calculated using the MegaWin software (Mega Electronics, Finland). As some patients had unilateral pain, the left and right masseter muscles were analyzed separately. For example, for patient A, the left and right muscles were designated A1 and A2, respectively, and were treated as individual data points in the statistical analysis. Representative values for each participant were obtained from the mean of three repetitions.

To compare masseteric activity between rest and Omax within the same group, the average percentage increase was calculated using the following formula:

\(\underline{p}\)difference: the average percentage increase from rest to Omax

\(\:{V}_{i}^{Omax}\) : the potential at Omax.

\(\:{V}_{i}^{rest}\) the potential at rest.

Potential values were also measured during MVC to quantify masseteric activity during Omax. The potential at Omax, expressed as a percentage of MVC, was used to assess the level of masseteric muscle contraction.

In patients with myofascial pain, the relationship between the pain level and masseteric potential during Omax was analyzed. Pain intensity was categorized into three levels: level 1 (pain VAS ≤ 40 mm), level 2 (pain VAS > 40 mm and ≤ 70 mm), and level 3 (pain VAS > 70 mm). The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used for this analysis.

A post hoc power analysis was employed to evaluate the sample size effect and power of this study. The Kruskal- Wallis test was used to calculate the epsilon-squared (ε²) value and convert ε² to Cohen’s f, f = sqrt ε² / 1 - ε². Subsequently, the effect size f and the total number of muscles were used to calculate the statistical power (1-β err prob) of the results27.

Differences between the four groups in EMG potential at rest and at Omax were analyzed using the Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis tests (one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), non-parametric)28. Post hoc tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test or Student-Newman-Keuls test were subsequently applied. Friedman’s ANOVA test was used to evaluate potential differences among experimental processes within each group, followed by Wilcoxon tests for post hoc analysis when a significant effect was observed.

Results

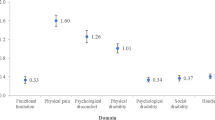

Masseter muscle potential varies from rest to Omax tasks

Figure 2 shows the average masseteric potentials of the four groups during rest and Omax. The DD and healthy groups showed no significant potential difference between rest and Omax. In contrast, the DD + M and M groups showed a significant potential difference between rest and Omax (p < .001). Additionally, significant differences were observed among the four groups during the Omax task (p < .001). The specific intergroup data analyses are presented in Table 2. The average and maximum potentials during Omax in the DD + M and M groups were significantly different from those in the healthy and DD groups, respectively (p < .001). In contrast, no significant differences were observed between the healthy and DD groups (Table 2).

The average rate of increase from rest to Omax in each of the four groups was calculated and presented in Table 3. The DD + \(\underline{M}\)difference and M groups exhibited a significantly higher potential increase (p < .001) from rest to Omax than the healthy and DD groups. However, no significant differences were found between the healthy and DD groups or between the DD + M and M groups. In addition, no significant potential differences between the four groups were observed during rest.

Masseteric contraction during Omax

The MVC potential and rate of Omax/MVC potentials were used to evaluate the degree of contraction of the masseter muscle during clenching and Omax (Table 2). The M group showed a significantly lower MVC potential than the healthy group (p < .05) but no other differences were observed. Regarding the rates of Omax/MVC (%), the DD + M and M groups showed significantly higher rates than the healthy group (p < .001). The average contraction degree of the masseter muscle during Omax reached 67.18% (average potential) and 87.81% (maximum potential), compared with 12.81% and 15.73% respectively in the healthy group.

Correlation between pain level and Omax potential

The results of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients are presented in Table 4. Weak correlations were observed between the pain VAS score and maximum potential during Omax (r = .376, p < .05). No significant correlations were found between pain VAS scores and the average potential during MO (r = .170, p > .05). The average potentials during Omax showed a moderate correlation (r = .677, p < .001) with the maximum potentials during Omax.

Discussion

One of the main goals of this experiment was to detect differences in electromyography patterns of the masseter muscles from rest to Omax between patients with LMO and myofascial pain and those with LMO and disc displacement disorders. The null hypothesis postulating that there was no difference in masseter muscle activity during Omax between patients with LMO and disc displacement and those with LMO and myofascial pain was rejected. The DD and M groups showed significant differences in masseter muscle activity during Omax. This study also aimed to determine the relationship between masseter muscle activity and pain levels. Our data provide some support for this relationship, as the pain VAS score showed a weak correlation with masseteric activity.

Our research revealed that the resting potentials among all four groups showed no significant differences, which is consistent with previous research29,30,31. However, some studies indicated that patients with TMD showed higher masseteric activity during rest than control groups, with moderate evidence from a meta-analysis32,33. As shown in Fig. 2, a higher masseteric potential was observed during rest in a few patients with TMD; however, this was not continuous. It appeared more like intermittent peaks during the five-minute rest period. After averaging the resting potential over five minutes, the potential difference between patients with TMD and healthy individuals was not significant. Recent reviews have also mentioned that variability in methods and analyses may be related to the varied results31.

The masseter muscle showed lower EMG activity during Omax in healthy people than in patients with TMD34. Our study showed similar results between healthy individuals and patients with TMD and myofascial pain. However, in patients with TMD and disc displacement, the same lower masseteric activities during Omax were observed as in healthy individuals. Yamaguchi et al. reported that patients with TMD and temporomandibular joint lock showed lower masseteric EMG activity than patients with myofascial pain during Omax35. However, details of the disc location and the shape of the condyle were not mentioned in the report.

Our study assessed the morphological condition of the temporomandibular joint using MRI and excluded patients with degenerative joint disease, ankylosis, trauma history, lateral disc displacement, and those who underwent orthodontic treatment. This reduced the interference of LMO caused by other pathologies in this study, allowing a better focus on masseteric activity during functional movement in the common subgroup of TMD, i.e., disc displacement. As shown in Fig. 2, the DD group showed no potential difference in masseter muscle activity between rest and Omax. This finding confirms that patients with anterior disc displacement without myofascial pain may have normal masseter muscle activity during mouth opening. This suggests that the main limitation in mouth opening is disc displacement.

The myofascial pain (M) group displayed increased masseteric activity from rest to Omax and lower MVC during clenching, which is consistent with previous studies20,36. Some researchers have reported that the EMG activities of the masticatory muscles were higher than those of controls during mouth opening under painful conditions22,29,37. Increased masseteric activity, which is antagonistic to mouth opening, may lead to LMO. As shown in Table 2, the average degree of contraction of the masseter muscle during Omax reached 67.18% MVC and 87.81% MVC in the M group. Compared with the respective results of 15.73% MVC and 12.81% MVC shown in the healthy group, the higher masseteric contraction may influence the mouth opening movement.

However, not all the patients with myofascial pain in our study exhibited significantly increased masseteric activity during Omax. Interestingly, our findings indicated that lower pain VAS scores showed a weak correlation with reduced muscle response. Similarly, Maulina et al. reported a positive correlation between experimental pain levels and muscle activity17. However, more evidence is needed to support the relationship between pain levels and muscle response in clinical settings. The DD + M group, which comprised the majority (54.1%) of the patients, exhibited two distinct masseteric EMG patterns during Omax. Some groups displayed a minimal potential increase, resembling that of the DD group, whereas others showed a more substantial increase, similar to that of the M group. In cases of low masseteric potential, pain may be secondary to disc displacement or may originate from other body sites, as indicated in previous studies29. Conversely, in patients with high masseter muscle activity exceeding 40% MVC, intensified contraction may contribute to LMO.

This study had some limitations. First, the number of patients in each TMD subgroup was not equal, and the sample size was small. Although Cohen’s d calculation indicated a medium to large effect size for this study, there may be errors in the power of this study owing to the limitations of the post hoc power analysis. Second, time deviation bias and the absence of MRI scans in healthy volunteers must be acknowledged. Despite employing DC/TMD diagnosis criteria with high sensitivity (≥ 0.70) and specificity (≥ 0.95) for joint dysfunctions2, it is conceivable that some healthy volunteers with slight disc displacement may have been included in the control group. Third, this study excluded patients with arthralgia and those with myofascial pain only, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to individuals with joint-related pain. Future research should incorporate arthralgia cases to provide a more comprehensive understanding of TMD-related muscle activity.

Based on the current research findings, our study has revealed a distinct coactivation of masseteric activity during maximum mouth opening in healthy volunteers, patients with LMO and temporomandibular disc displacement, and patients with LMO and myofascial pain. More evidence is needed regarding the relationship between multiple pain models, muscle responses, and jaw limitations. Our findings offer insights into masseter muscle movement during maximum opening and contribute to a better understanding of whether the origin of LMO is myogenic or arthrogenic.

Average potential during rest and maximum opening (Omax) in four groups. DD: Disc Displacement. M: Myofascial pain. a: Wilcoxon test. Potential during rest and Omax was compared within one group. b: Kruskal-Wallis test. Potential during Omax was compared between the four groups. Post hoc: Mann-Whitney U test.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at Osaka University. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [Ryota Takaoka] on request.

Change history

15 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08973-5

References

Ohrbach, R., Gonzalez, Y., List, T., Michelotti, A. & Schiffman, E. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) clinical examination protocol: version 02 June 2013; (2014). Available at ubwp.buffalo.edu/rdc-tmdinternational/ Accessed June 02, 2013.

Schiffman, E. et al. International RDC/TMD consortium network, international association for dental research, orofacial pain special interest group, international association for the study of pain. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the international RDC/TMD consortium network** and orofacial pain special interest group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 28, 6–27 (2014).

Schiffman, E. & Ohrbach, R. Executive summary of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders for clinical and research applications. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 147, 438–445 (2016).

Masumi, S., Kim, Y. J. & Clark, G. T. The value of maximum jaw motion measurements for distinguishing between common temporomandibular disorder subgroups. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 93, 552–559 (2002).

AlHammad, Z. A., Alomar, A. F., Alshammeri, T. A. & Qadoumi, M. A. Maximum mouth opening and its correlation with gender, age, height, weight, body mass index, and temporomandibular joint disorders in a Saudi population. Cranio 39, 303–309 (2021).

Peck, C. C. et al. Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J. Oral Rehabil. 41, 2–23 (2014).

Rapidis, A. D. et al. Trismus in patients with head and neck cancer: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Clin. Otolaryngol. 40, 516–526 (2015).

Sidebottom, A. J. How do I manage restricted mouth opening secondary to problems with the temporomandibular joint? Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 51, 469–472 (2013).

Pérez del Palomar, A. & Doblaré, M. An accurate simulation model of anteriorly displaced TMJ discs with and without reduction. Med. Eng. Phys. 29, 216–226 (2007).

Bouman, M. A., Dijkstra, P. U., Reintsema, H., Roodenburg, J. L. & Werker, P. M. Surgery for extra-articular Trismus: a systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 54, 253–259 (2016).

JafriMS Mechanisms of myofascial pain. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 523924 (2014).

Takaoka, R. et al. Involvement of an FTO gene polymorphism in the temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Clin. Oral Investig. 26, 2965–2973 (2022).

Xiong, X. et al. MRI of temporomandibular joint disorders: recent advances and future directions. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 54, 1039–1052 (2021).

Szyszka-Sommerfeld, L., Machoy, M., Lipski, M. & Woźniak, K. The diagnostic value of electromyography in identifying patients with pain-related temporomandibular disorders. Front. Neurol. 10, 180 (2019).

Pilkar, R. et al. Use of surface EMG in clinical rehabilitation of individuals with SCI: barriers and future considerations. Front. Neurol. 11, 578559 (2020).

Wan Daud, W. M. B., Yahya, A. B., Horng, C. S., Sulaima, M. F. & Sudirman, R. Features extraction of electromyography signals in time domain on biceps brachii muscle. Int. J. Model. Optim. 3, 515–519 (2013).

Maulina, T. et al. The effects of experimental temporalis muscle pain on jaw muscle electromyographic activity during jaw movements and relationships with some psychological variables. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 32, 29–39 (2018).

Amhamed, M., Whittle, T., Gal, J. A. & Murray, G. M. Simultaneous noxious stimulation of the human anterior temporalis and masseter muscles. Part II: effects on jaw muscle electromyographic activity. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 33, 426–439 (2019).

Amhamed, M., Whittle, T., Gal, J. A. & Murray, G. M. Simultaneous noxious stimulation of the human anterior temporalis and masseter muscles. Part I: effects on jaw movements. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 33, 413–425 (2019).

Szyszka-Sommerfeld, L., Machoy, M., Lipski, M. & Woźniak, K. Electromyography as a means of assessing masticatory muscle activity in patients with pain-related temporomandibular disorders. Pain Res Manag. ; 2020: 9750915. (2020).

Lauriti, L. et al. Influence of temporomandibular disorder on Temporal and masseter muscles and occlusal contacts in adolescents: an electromyographic study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 15, 123 (2014).

Pietropaoli, D. et al. Alterations in surface electromyography are associated with subjective masticatory muscle pain. Pain Res Manag. ; 2019: 6256179. (2019).

Peck, C. C., Murray, G. M. & Gerzina, T. M. How does pain affect jaw muscle activity? The integrated pain adaptation model. Aust Dent. J. 53, 201–207 (2008).

Ferreira, P. M., Sandoval, I., Whittle, T., Mojaver, Y. N. & Murray, G. M. Reorganization of masseter and temporalis muscle single motor unit activity during experimental masseter muscle pain. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 34, 40–52 (2020).

International Classification of Orofacial Pain. 1st ed. (ICOP) Cephalalgia ; 40: 129–221. (2020).

Kaya, K. et al. Diagnostic value of ultrasonography in the evaluation of the temporomandibular joint anterior disc displacement. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 38, 391–395 (2010).

Serdar, C. C., Cihan, M., Yücel, D. & Serdar, M. A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 31, 010502 (2021).

Vickers, A. J. Parametric versus non-parametric statistics in the analysis of randomized trials with non-normally distributed data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 5, 35 (2005).

Zieliński, G., Byś, A., Szkutnik, J., Majcher, P. & Ginszt, M. Electromyographic patterns of masticatory muscles in relation to active myofascial trigger points of the upper trapezius and temporomandibular disorders. Diagnostics (Basel). 11, 580 (2021).

Manfredini, D. et al. Surface electromyography of jaw muscles and kinesiographic recordings: diagnostic accuracy for myofascial pain. J. Oral Rehabil. 38, 791–799 (2011).

Pelai, E. B., Foltran-Mescollotto, F., de Castro-Carletti, E. M., de Moraes, M. & Rodrigues-Bigaton, D. Comparison of the pattern of activation of the masticatory muscles among individuals with and without TMD: a systematic review. Cranio 41, 102–111 (2023).

Dinsdale, A., Liang, Z., Thomas, L. & Treleaven, J. Is jaw muscle activity impaired in adults with persistent temporomandibular disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 48, 487–516 (2021).

Szyszka-Sommerfeld, L., Sycińska-Dziarnowska, M., Spagnuolo, G. & Woźniak, K. Surface electromyography in the assessment of masticatory muscle activity in patients with pain-related temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. Front. Neurol. 14, 1184036 (2023).

Inoue, S. et al. Effect of the location of chewing on facial and jaw muscles activity and the mandibular movement. J. Osaka Univ. Dent. Sch. 34, 89–95 (1994).

Yamaguchi, T. et al. Electromyographic activity of the jaw-closing muscles during jaw opening–comparison of cases of masseter muscle contracture and TMJ closed lock. J. Oral Rehabil. 29, 1063–1068 (2002).

Ardizone, I. et al. Electromyographic study of activity of the masseter and anterior temporalis muscles in patients with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction: comparison with the clinical dysfunction index. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 15, e14–e19 (2010).

Baad-Hansen, L., Hara, S., Marumo, Y., Miles, T. & Svensson, P. Effect of experimental pain on EMG-activity in human jaw-closing muscles in different jaw positions. Arch. Oral Biol. 54, 32–39 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) supported a part of this study (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) #19K10204, #23K09251, #23K16088).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaoyu Lin: Deta collection, Writing- Original draft preparation, Ryota Takaoka: Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Daisuke Moriguchi: Methodology, Shion Morioka: Software, Deta collection, You Ueda: Visualization, Investigation. Rie Yamamoto: Investigation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Emi Ono: Software, Validation.: Shoichi Ishigaki: Conceptualization Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Abstract. In addition, the guiding lines indicating the subject inclusion/exclusion process were missing from Figure 1. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, X., Takaoka, R., Moriguchi, D. et al. Electromyographic evaluation of masseteric activity during maximum opening in patients with temporomandibular disorders and limited mouth opening. Sci Rep 15, 12743 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97877-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97877-5