Abstract

In non-linear dielectric spectroscopy of yeast suspensions, previous studies distinguished nonlinear interface behavior from yeast membrane-induced currents by comparing power spectra of solutions with and without yeast. However, this method might be inaccurate because the effect of yeast can not be considered merely an additive contribution. In fact, the presence of yeast on the electrode surface can alter the voltage drop reaching the electrode, thus changing the nonlinear electrode response. No prior research has investigated the effect of yeast presence on the electrode surface using a nonlinear mathematical model. Here, we used a four-electrode system to record responses from solutions when applying a single-frequency voltage of 23 Hz. Using the Butler-Volmer model, we showed that yeast presence elevates a model parameter affected by ion concentration at the interface or mass transfer to the electrode. Model results suggest that the increase in the third harmonic, contrary to previous assumptions, may not be entirely attributed to the ionic current of the yeast membrane’s proton pump. Our results are significant for distinguishing the biological effects of cells in the solution from the interface effects. It can also be used for online monitoring of cell growth in the environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the nonlinear dielectric spectroscopy (NLDS) of biological solutions, an electrical signal with a single frequency is used as input. Because the biological system being studied is nonlinear, higher frequencies are obtained in addition to the first frequency in the output spectrum. Examining higher harmonics gives us information about the nonlinear nature of the biological system. From 1990 to 2023, several studies have investigated the nonlinear spectrum obtained from solutions containing Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast (SC yeast)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. In these studies, it has been shown that the presence of yeast causes a change in the amplitude of the third harmonic so that the inhibition of the ionic activity of the yeast membrane can reduce this harmonic in a series of excitation ranges and increase it in another series of voltages7,8.

To get rid of interface-induced harmonics, researchers have already looked at the difference between the power spectra of solutions with and without yeast (after centrifuging to separate the yeast) at the same frequency and amplitude. They assume Only the harmonics resulting from the yeast membrane activity persist in this approach1,8.

Several research studies have examined the linear spectrum of biological solutions and have observed that yeast on the electrode surface can alter the equivalent circuit model of the system being studied, either by introducing a series or parallel element9,10. On the other hand, The electrode-electrolyte interface (EEI) impedance is nonlinear under high amplitude excitation (more than 100 mv)11. As a result, it appears that the presence of yeast can influence the nonlinear behavior of the interface, and their effects cannot simply be reduced by treating them as additive elements.

The mathematical modeling of nonlinear currents resulting from the EEI is a common approach in fuel cell research12,13,14. The absence of a mathematical model that accounts for the impact of yeast presence on the nonlinear behavior of EEI impedance is obvious. Previous research in this field focused on the relationship between the third harmonic amplitude and the activity of ion channels on the membrane. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the effect of yeast on harmonics generated by nonlinear electrode-electrolyte currents, utilizing both mathematical modeling and experimental testing.

The majority of yeast investigations have utilized a four-electrode setup and gold electrodes to record the signal. To ensure data comparability, we likewise employ a similar recording approach. Furthermore, based on previous research, the frequency under investigation is 23 Hz, while the voltage stimulation varies between 0.8 and 3.5 V.

In linear spectroscopy of biological solutions, four-electrode systems are commonly used to eliminate interface effects. However, in nonlinear dielectric spectroscopy (NLDS), the nonlinear current induced in the solution by high-amplitude voltage also includes contributions from the interface. To accurately interpret the biological activity, it is essential to distinguish these interface effects from the actual solution behavior. In this study, we address this challenge for the first time by developing a mathematical model for the four-electrode system.

Additionally, we utilized CST software to model the electrode and solution container in detail and conducted low-frequency simulations to estimate the electric field distribution. This simulation provides a novel approximation of the electric field near the electrode and within the solution, which had not been explored in prior studies.

Materials and methods

Preparation of yeast suspension

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a yeast and its cells are round to ovoid with 5–10 μm in diameter. The yeast was cultivated in a YPD medium containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. To simplify the analysis and modeling of electrochemical processes at the electrode surface, Once the yeast reached the log phase of growth, the liquid medium containing the yeast cells was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellet was washed twice with a 30 mM KCl solution and then resuspended to a 30 mM KCl solution. This yeast suspension has been employed for all experiments. The number of yeast cells in the suspension was 3 × 108 per ml. The concentrations were measured by using the Neubauer Chamber.

To record data from the yeast-free solution, the yeast suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting liquid above the sediment, known as the supernatant, is then separated and used as the medium solution. Here, we used this solution as an ionic solution with the same content as the yeast suspension to evaluate the origin of harmonic generation.

To prepare dead yeast suspension, we bathed the sample in water at 70 °C for 3 min. The flow cytometry test results confirm the yeast state (dead). To assess the concentration effect, the concentration value was diluted by a factor of 1000 until the yeast concentration reached 3 × 105 cells per ml. The term “diluted solution” will be used to refer to this solution throughout the paper.

Configuration of electrodes

We used a 24-well plate with four holes designed at the top and bottom for electrode insertion to measure the nonlinear spectrum (see Fig. 1). The holes at the bottom of the plate secure the electrodes in place and prevent the electrode tips from entering the solution. Sharp electrode tips can create intense local fields. The electrodes have a diameter of 0.8 mm and a length of 3 cm. The solution is introduced into the well through the inlet hole as shown in Fig. 1. A schematic of the well dimensions, electrodes, and the electrode cleaning procedure previously presented15.

Experimental configuration

To provide clarity for the present study, this section summarizes the previously described experimental setup detailed in15. The original configuration, optimized for nonlinear spectroscopy measurements, was directly applicable to the present study without modifications. In this work, the setup was adapted to examine biological solutions containing yeast, enabling the analysis of nonlinear effects induced by yeast activity. Below, we outline the key components and methodologies employed in the setup, followed by a detailed explanation of circuit current calculation and voltage excitation.

Signal generation and application

A sinusoidal voltage signal of 23 Hz with amplitude ranging from 0.8 to 3.5 V was applied to the outer electrodes (referred to as needles 1 and 2 in Fig. 2a) using the Instek-AFG function generator. The device’s low harmonic distortion (< − 60 dBc) ensured precise signal application, making it suitable for nonlinear dielectric spectroscopy (NLDS) experiments.

Data acquisition and processing

Voltages at the central electrodes (needles 3 and 4) and across a series resistor (548 ohms) were recorded with and without amplification. The recorded signals were captured at 14-bit resolution using the USB6009 data acquisition board (Fig. 2a), with amplification achieved using a gain of 10. To improve signal accuracy and reduce noise, a differential amplifier utilizing AD826 operational amplifiers was employed.

For each solution, the circuit setup illustrated in Fig. 2a was implemented, where a series resistor was connected in line with the solution. The voltages across the middle electrodes (Vrecord) and the series resistor (VR) were recorded and subsequently processed in MATLAB. Circuit current was determined by dividing the voltage across the resistor by its resistance.

By analyzing the relationship between Vrecord and the circuit current, along with their harmonics, we confirmed that the intermediate solution exhibits linear and passive behavior (Zr in Fig. 5). Since the impedance of the solution remains constant in single-frequency experiments, this property allows us to calculate the solution current using only two inner electrodes without the need for a series resistor.

Since our study focuses on nonlinear current analysis, the presence of a series resistor would introduce a nonlinear voltage drop, affecting the harmonic-free assumption of the applied excitation. To prevent this distortion and ensure accurate harmonic analysis, the series resistor was removed. A buffer circuit following the signal source (Fig. 2a) minimized voltage drops across the internal resistance of the source. The nonlinear current was then determined by measuring the voltage across the middle electrodes and dividing it by the impedance. The equivalent circuit after removing the series resistor is shown in Fig. 5, and the resulting current waveform is depicted in Fig. 2b.

The voltage drop across the solution between electrodes 1–4 and 2–3 (Vsol in Fig. 5) was related to the inner electrode voltage (Vrecord) through a constant coefficient, determined via CST simulations. Given the known values of Vrecord and Vs, the Vsol parameter was calculated accordingly, allowing the measurement of interface overpotential (VEEI). Further details on this calculation method are available in15.

System validation and noise evaluation

The accuracy of the experimental method was validated using a circuit phantom as described by Treo et al.16. Results from experimental tests were compared with simulations performed in Spice, demonstrating excellent agreement. To evaluate noise levels and recording precision, deionized water served as a baseline. Harmonics in deionized water were below − 50 dBc, increasing to approximately − 30 dBc with the addition of ions (e.g., KCl). These results confirmed the sensitivity and precision of the system.

Harmonic analysis

To further examine the nonlinear behavior of the system, Temporal signals were analyzed using MATLAB’s “lsqnonlin” function, which determined both the magnitude and phase of each harmonic by aligning the signals with the 20th harmonic. This method yielded results consistent with the Fourier transform approach (utilizing a Hanning window with 50% overlap) while enabling precise phase measurements.

An example of the current time signal for a medium solution subjected to 1.8 V excitation is shown in Fig. 2b. Further details regarding signal generation and harmonic computation can be found in15. Using the lsqnonlin function, harmonic amplitudes and phases were extracted up to the 20th harmonic.

Reproducibility and stability of experimental data

Considering that biological solutions, such as yeast suspensions, may vary in cell density and physical conditions during each preparation, the following measures were taken to ensure the reliability of our results:

-

Intra-day experiments: After preparing 50 mL of yeast suspension, we performed spectroscopic tests in multiple wells within a single day. The number of repetitions for each suspension is provided in Table 1, second column.

-

Inter-day experiments: To account for potential variations in biological and physical conditions between different preparations, the experiments were also repeated on different days. The results obtained across different days were consistent, demonstrating the robustness and reliability of the data under varying conditions.

To ensure confidence in the reported findings, we carefully designed the experiments to minimize potential sources of variability.

The nonlinear model of recorded current

The total current in the Randles circuit (equivalent circuit of EEI17) combines two types of currents: faradic and non-faradic (capacitive). The mathematical representation of the interface equivalent capacitor demonstrates that the capacitor’s value is dependent on the voltage Amplitude, and its mathematical equation significantly contributes to the generation of even harmonics in the overall current18. Previous research has demonstrated that when subjected to low-frequency and high-amplitude excitation, the behavior of the interface becomes nonlinear, mostly due to the faradic current (electrochemical reactions occurring on the surface of the electrode)19,20,21. Furthermore, given our objective of analyzing odd harmonics, we solely focus on the non-linear mathematical representation of the faradic current as the source of odd harmonic creation.

The Butler-Volmer equation (Eq. 1) models the non-linear faradic current by relating it to ion concentration and the rate of redox reactions21.

The exchange current is represented by\(~{I_0}\). The concentrations of oxidation and reduction products on the electrode’s surface are denoted by \({C_o}\left( {0,t} \right)\) and\(~{C_R}\left( {0,t} \right){\text{~}}\)respectively, while,\({\text{~}}C_{R}^{{\text{*}}}\) and \(C_{o}^{{{\text{*~}}}}\)represent these concentrations in the bulk solution. The transfer coefficient α vranges from 0 to 1, with n indicating the number of electrons exchanged per mole in a redox reaction. In this context, we assume a symmetric and single electron transfer with α = 0.5 and n = 1. R is the gas constant, T represents the absolute temperature, and F denotes the Faraday constant.

Here VEEI is the EEI overpotential amplitude. The interface overpotential differs from the voltage applied to the external electrodes (Signal Generator output). The applied voltage amplitude from the source varies between 0.8 and 3.5 volts, while the interface overpotential amplitude (VEEI) ranges from 0.1 to 1 V. The method for calculating the EEI overpotential (\(\:{E}_{stim}\)) is provided elsewere15. In this study, we have utilized the interface overpotential for a more detailed examination, as this voltage influences the events occurring on the electrode surface.

We first define the parameter gamma (Eq. 2) to facilitate data analysis.

Here A is the electrode surface area and \({k_0}\) the standard rate constant.

Extracting the odd harmonic from the Taylor expansion of this equation leads to the following relationship for the odd harmonics (Eq. 3) (The Harmonic calculation details are provided in Supplementary Material I).

The ratio between the third harmonic and the first harmonic is a frequently employed metric in literature to assess and evaluate the harmonics resulting from the presence or absence of yeast in the solution. The H1 relationship in Eq. (3), which describes current harmonics, shows that the size of the first harmonic is greatly affected by the magnitude of the odd harmonics. Furthermore, if the presence of yeast impacts the value of the odd harmonic, this effect is manifested by a non-linear coefficient in the first harmonic. Hence, using the ratio of the third harmonic to the first harmonic as a criterion to analyze the harmonics induced by yeast appears to be inaccurate. Here, we define the γ parameter and evaluate the effect of yeast on it.

The theoretical model employed in this study remains unchanged from our previous work15. We have redefined the equations in this paper for a better understanding of the result analysis. However, the novelty of this study lies in the application of the model to biological solutions and the extraction of model parameters for solutions with and without yeast cells.

Results

To assess the impact of yeast presence on the third harmonic, we initially examine the influence of living yeast at two distinct concentrations. Subsequently, we proceed to evaluate the effect of dead yeast on the behavior of the third harmonic.

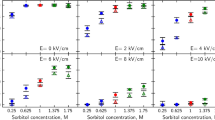

The effect of live yeast and varying its concentration

We analyze the impact of live yeast on the third harmonic pattern. Figure 3 demonstrates the correlation between fluctuations in the third harmonic and alterations in the amplitude of the EEI overpotential (VEEI).

Representation of the third harmonic of total current in yeast suspension and its medium Vs the interface overpotential (frequency: 23 Hz). A, B, and C illustrate the different sections of the diagram. The subscript “s” denotes the yeast suspension, and the subscript “m” denotes the medium. The error bars indicate the standard deviation.

Figure 3 shows that adding yeast leads to a change in the third harmonic pattern. The graphs of the third harmonic for both yeast-containing and yeast-free solutions display the same pattern: an initial increase (A), followed by stabilization (B), and a subsequent increase (C). The indices ‘s’ and ‘m’ refer to suspension and medium, respectively. The addition of yeast causes an increase in the initial voltage of area B, resulting in a shift towards higher voltages. (\({\text{V~threshold~}}{B_s}>{\text{~V~threshold~}}{B_m})\). The value of this threshold voltage will be used in the subsequent sections of the article to calculate the interface overpotential.

The third harmonic result in Fig. 4 demonstrates that when the yeast concentration is diluted from 3\(\times {10^8}\) (Thousand-fold Dilution), its impact on the results becomes insignificant.

The concentration of 3\(\:\times\:{10}^{3}\) has been replicated, yielding the same result; however, the corresponding data is not included in this study.

In Fig. 4, the horizontal axis represents the voltage drop across the EEI region. In other studies examining the linear impedance of solutions containing cells, the presence of yeast on the electrode surface can be considered a series impedance combined with the EEI impedance. Relative to the yeast-free solution (medium), this voltage drop across the yeast layer results in a lower voltage reaching the interface for an equivalent applied voltage (Signal Generator output).

To facilitate a more precise comparison between solutions with and without yeast, it is necessary to calculate the voltage reaching the EEI. Since the equivalent circuit model provides a framework for understanding voltage distribution, we first analyze its structure to determine how yeast alters the system’s electrical behavior. Further elucidation will be provided subsequently through the examination of a circuit model.

Effect of yeast on the equivalent circuit model

First, we investigate how yeast can be represented in the circuit model for the system under investigation. The Equivalent circuit model can be analyzed in both the presence and absence of yeast to determine the EEI impedance (Fig. 5). This analysis helps quantify the impact of yeast on nonlinear behavior at the interface.

As discussed in section “Data acquisition and processing”, we observed that the intermediate solution (Zr ) exhibits passive behavior. Thus, based on previous studies in the field of nonlinear spectroscopy4, we attribute the nonlinear behavior to phenomena occurring at the electrode surface (ZEEI). Consequently, active elements have been incorporated into this part of the circuit. These active components become particularly relevant when analyzing harmonic current responses. For the harmonic current calculations, the circuit shown below (Fig. 5), which excludes the series resistor, was utilized (details provided in section “Data acquisition and processing”).

Figure 5 represents a circuit model equivalent to a four-electrode measurement system, where the dashed line over the resistor symbol in Fig. 5 indicates the presence of active nonlinear elements in this branch. For the equivalent circuit of the interface (ZEEI), as noted in previous studies16,19, an active circuit model containing diodes (as shown in ths Fig. 5) can be employed. This means that the behavior of the system is voltage-dependent: if the interface voltage (VEEI) remains low, the diodes remain inactive, resulting in a linear response. However, at higher voltages, diode activation necessitates nonlinear analysis.

Modeling yeast as a circuit element and analyzing its influence on the equivalent circuit components is complex. However, experimental results indicate that the presence of yeast alters the voltage drop across the interface, leading to a measurable shift in voltage distribution (Fig. 3, initial voltage of area B). This effect is further illustrated in Fig. 4, which demonstrates that a decrease in yeast concentration (due to reduced yeast presence on the electrode surface) does not significantly alter the initial voltage of area B or the third harmonic amplitude.

Based on our experimental data (Fig. 3), we assumed that the voltage drop across the yeast membrane is insufficient to produce measurable nonlinear currents or that such currents, if present, are below the detectable range of our setup (a more detailed numerical explanation is provided in the “Discussion” section). As a result, in our initial modeling, yeast was treated as a passive element to facilitate the first-order approximation of voltage changes. However, future modifications to the model could incorporate its active effects.

Yeast affects the nonlinear behavior of the interface by altering the voltage distribution. it may also influence the diode branch elements by modifying the ionic concentration near the electrode through physical interaction. This effect could lead to variations in impedance characteristics, which require further investigation through impedance spectroscopy over a broad frequency range. However, in this study, due to:

-

Limitations of the data acquisition card in measurable frequency ranges.

-

The use of a specific frequency for comparative purposes (as reported in the literature).

We did not have access to such frequency data. Consequently, our analysis was restricted to a single frequency measurement. Given this limitation, instead of employing an active circuit model, we utilized the Butler-Volmer equation to analyze the circuit current and extract its parameters for solutions with and without yeast.

Effect of yeast on the mathematical model

As mentioned earlier, due to the single-frequency nature of our data, we cannot precisely calculate the yeast impedance and voltage drop across it with the use of equivalent circuit model. However, the observed voltage shift at the initial voltage of area B provides an indirect estimate of this effect. Thus, we derive this shift from the experimental data and incorporate it into the calculation of VEEI.

After correcting for the EEI overpotential and removing the yeast overvoltage, we examine the third harmonic from a mathematical modeling perspective to assess the yeast’s impact on the model parameter (\(\:\gamma\:\)). Using the Butler-Volmer equation as a mathematical model for the faradic currents, we analyze the current obtained from the experimental data to determine the values of H5 and H3. By substituting these values into the H3 relation in Eq. 3, we can then calculate the unknown parameter (\(\:\gamma\:\)).

The results indicate an exponential dependence of γ on VEEI, suggesting a significant nonlinear relationship. Consequently, the function a×exp(b×VEEI) was fitted to the obtained values, and the result, yielding an R-square value above 95% (Table 1). Additionally, the Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed a normal data distribution, allowing statistical significance to be assessed via an independent t-test. The results (Table 1) indicate that while no significant difference in the γ coefficient (a) exists between the diluted yeast suspension and the medium solution, a significant difference is observed between the yeast suspension and both other conditions. This suggests that yeast at high concentrations affects the interfacial current model. The results presented in Table 1 reflect one of the experimental days, as the data from other days were consistent and confirmed the same trends.

Now, if we assume that the values of n, A, and k are the same in two cases (with and without yeast), and \({\text{\varvec{\upalpha}}}\) is equal to 0.5, then the parameter \(\gamma\) (Eq. 5).

Here, it is assumed that \(C_{R}^{{\text{*}}}{\text{~}}\)equals \(C_{o}^{{\text{*}}}\), denoted as C and a significant portion of C is due to KCl.

Further analysis of the γ parameter suggests its dependence on both the concentration of reactive species and the ratio of their surface-to-bulk concentrations. Since yeast affects ionic concentrations near the electrode surface, it could either modify charge transfer rates or alter diffusion properties22,23. Our previous investigations on KCl solutions of varying concentrations15 demonstrated that increasing KCl concentration leads to an increase in the exponential coefficient (a) in the γ fitted equation. Notably, the a value in the yeast suspension is more than twice that in the medium (Table 1), suggesting that yeast-induced transmembrane ion exchange significantly impacts the electrochemical system. Further studies are required to distinguish whether this effect arises primarily from ionic redistribution or increased electron transfer kinetics.

The physical appearance of yeast on the electrode’s surface

Given the vertical and three-dimensional arrangement of the electrodes in the culture container (well) (Fig. 1), capturing a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the electrode surface is not feasible. However, a specific arrangement was established to verify the existence of viable yeast on the electrode surface, and a photograph of the electrode surface was obtained. Figure 6 illustrates the electrode surface in two distinct states: one with stimulation applied and one without. The yeast cells are visible on the electrode surface under stimulation. Indeed, in order to facilitate imaging and conduct this test, the yeast concentration has been reduced, allowing for visualization of the yeast population on the surface. As observed in the diagram of the third harmonic (Fig. 4), with the dilution of the yeast, the effect of the yeast on the harmonic reduces, and in this photo (Fig. 6), it is also clear that the vacant space of the yeast rises with the decrease in concentration on the electrode surface.

The microscopic image of the drive electrode surface. (a) The Schematic diagram of the setup designed for capturing images of the electrode surface. (b) When stimulation is applied and yeast cells are present on the electrode surface. (c) The electrode surface without any stimulation. The arrow indicates the yeast location (400X).

The effect of dead yeast

Figure 7 depicts the third harmonic of the solution under two conditions: with and without yeast in a non-living state. It illustrates that the inclusion of deceased yeast did not exert a substantial impact on the third harmonic. By subjecting the yeast to heat, the capacitance of the solution remains constant regardless of the presence or absence of yeast, indicating that the yeast does not adhere to the electrode surface. Presumably, the heat likely resulted in the deterioration of the outer membrane layer, which had a significant impact on the yeast’s capacitance and its absorption to electrode24. This finding supports the previous discourse regarding the existence of yeast on the electrode surface and its impact on the third harmonic.

Near electrode electric field estimation

For the estimation of the electric field near the stimulating electrode and the investigation of its distribution within the solution, a detailed simulation was performed using CST software. We conducted comprehensive numerical simulations where the electrodes, solution, and experimental chamber were precisely modeled, and their physical and electrical properties were carefully defined. The schematic of the well, yeast solution, and electrodes, along with their dimensions, are shown in Fig. 8a.

(a) Schematic of the well and electrodes, including their dimensions. (b) Electric field distribution in a cross-section of the solution when a 1.8 V sinusoidal voltage is applied to the outer electrodes. (c) Relationship between the maximum electric field near the electrodes and the applied voltage amplitude.

The simulations were performed in a low-frequency environment under quasi-static conditions. A voltage was applied to the two stimulating electrodes, and the electric field distribution around the electrodes and within the solution was then obtained (Fig. 8b). The maximum electric field strength near the surface of the stimulating electrode was calculated for various applied voltages. To the best of our knowledge, this level of detailed electric field modeling has not been reported in previous studies using a 4-point electrode setup.

In electrical spectroscopy, low voltage amplitudes (typically in the range of tens of millivolts) are commonly used to minimize nonlinear effects at the electrode-solution interface. This approach ensures that the observed results are primarily attributed to the properties of the biological solution. However, such low voltages generally produce weak electric fields, which may not be strong enough to effectively stimulate nonlinear processes.

In contrast, nonlinear spectroscopic studies, including those involving yeast cells, often require electric fields in the range of 1–5 V/cm7. Generating these field strengths necessitates applying higher voltages (on the order of volts) to the electrodes. This high voltage causes the emergence of nonlinear electrode-interface behavior, which is a crucial point for the analysis of the results. Therefore, in this study, the term “high-amplitude” specifically refers to voltages greater than those typically used in linear spectroscopy. These higher voltages are essential for generating the stronger electric fields required for nonlinear effects. The relationship between voltage and electric field is shown in Fig. 8c.

Discussion

Through their research, Treo and Mclellan et al.25 successfully eliminated the interface effect from the data by creating a measurement device specifically designed for this purpose. They determined that, once the interface effect was removed, the yeast suspension did not generate any significant odd harmonics. Additionally, the Felice group10,26 conducted two separate studies demonstrating that yeast can be regarded as a series element with an interface, which impacts current harmonics.

Miller7,8 demonstrated that the presence of yeast can lead to an increase in third harmonic stimulation in certain domains, while in other domains it can cause a decrease. This phenomenon is attributed to the functioning of the hydrogen pump on the yeast membrane. To eliminate the interface effect, similar data from the power spectrum obtained from both the yeast solution and the solution without yeast were subtracted. Despite this approach, it is still unclear whether the observed harmonic changes result purely from yeast membrane currents or if residual interface effects persist. Based on our findings, it appears that this data differentiation method is ineffective in eliminating the interface effect. Consequently, what persists are the interface harmonics rather than the harmonics resulting from yeast membrane currents.

In previous studies, the currents on the yeast membrane have been identified as the source of the third harmonic. We are now examining this possibility. Based on the data in Fig. 4, when the maximum voltage applied to the yeast layer on the electrode surface is approximately 200 mV, considering the yeast’s diameter of 10 μm, the electric field generated on the yeast layer is equivalent to 20 kilovolts per meter (kV/m). This electric field can cause a change in the voltage across the yeast membrane and result in the occurrence of ionic currents on the electrode surface. Assuming that the hydrogen pump is the source of the membrane currents, it can generate a maximum current of 10 µA/cm226. If the yeast surrounds the electrode and considers the electrode’s dimensions (lateral area A = 2πrh = 0.502 cm2), the yeast membrane activity produces a total current of 5.02 microamps. However, this current is significantly smaller than the total current of the circuit, which is at a minimum of 10 µA. Thus, although the membrane currents may contribute to harmonic generation, their direct measurement remains challenging.

This work involved examining the alterations in the third harmonic resulting from the inclusion of yeast. We achieved this by using mathematical modeling to analyze the nonlinear current generated at the interface of the gold electrode surface. The third harmonic pattern remains consistent in both the yeast-containing and yeast-free solutions. We demonstrated that to examine the impact of yeast, it is necessary to eliminate the interface effect by modeling. Therefore, rather than relying on simple data subtraction, we employed a more robust modeling approach to accurately assess the yeast’s influence. Here we showed that Subtracting the ratio of the third harmonic to the first in two samples, one with yeast and one without, can yield inaccurate outcomes. Subtracting the corresponding harmonic data requires accurate calculation of the interface voltage, which we have successfully adjusted in this study.

Our findings suggest that although it may not be feasible to directly measure the nonlinear current of the membrane, changes in concentration resulting from yeast membrane activities can be identified by analyzing the γ parameter. This is because the membrane’s hydrogen pump, known to be the source of the nonlinear current, expels one potassium ion from the cell for every two hydrogen ions it absorbs26. Variations in this pump’s activity can lead to changes in the potassium ion concentration in the solution. This concentration change is not significant for a small number of yeast cells, and our results showed no notable difference in diluted yeast samples (Fig. 4); however, it becomes significant when the yeast cell count is high. Thus, γ serves as an indirect yet reliable parameter for assessing the influence of yeast on electrochemical behavior.

When we identify the source of harmonics as the nonlinear behavior of the interface and aim to investigate the effect of yeast on this behavior, we must first accurately model the nonlinear behavior of the interface. In a previous study, we developed an appropriate experimental setup and method for this investigation. In the present study, we used a similar method and setup as the previous article, but this time to examine the nonlinear behavior of the yeast solution. While our previous study focused on general interface nonlinearities, this work specifically addresses the influence of biological components on these nonlinearities, offering a novel perspective on harmonic generation in bioelectrochemical systems. Understanding how yeast affects this behavior and how to model it is itself a challenging process. Therefore, this study analyzes different data compared to the previous article and presents a new and different perspective on the analysis of harmonics in biological solutions, especially when the stimulation amplitude exceeds the threshold of the linear behavior of the interface. These findings are summarized in Table 1, offering a fresh perspective on harmonic analysis in biological systems.

Furthermore, we conducted numerical simulations to approximate the near-electrode electric field, a novel contribution not previously reported for needle-like four-electrode setups. This simulation allows for a more accurate understanding of the local field distribution and its interaction with biological entities like yeast.

The upcoming research can involve altering the yeast’s condition through the use of glucose and an inhibitor to examine their impact on the 3rd harmonic and γ parameters. Based on the results of this study, we predict that by adding an inhibitor and reducing the activity of the hydrogen pump, thereby decreasing the potassium concentration expelled by the yeast, the exponential coefficient of the γ parameter and consequently the third harmonic will decrease. Such findings could provide further insight into the bioelectrochemical interactions at the electrode interface, paving the way for potential applications in biosensing and microbial fuel cells. This prediction is consistent with the findings of previous studies8. In a forthcoming article, we have theoretically examined this issue.

Conclusion

In this study, we examine the impact of yeast presence on the electrode surface on the nonlinear current response of yeast suspension to low-frequency excitation. This effect is distinguished from interface nonlinear behavior using the Butler-Volmer mathematical model. We identify a model parameter related to concentration, electron transfer rate on the electrode surface, and the effective surface area of the electrode, which can be increased by the presence of yeast. This increase indicates that yeast can locally alter ion concentration on the electrode surface. This ion change necessitates the activity of transmembrane channels such as the H+_ATPase pump. Further investigation is required to explore the role of the nonlinear properties of the yeast membrane, which can be studied by eliminating these effects.

Investigating membrane activities and cell adsorption to the electrode requires generating a strong field within the biological solution. A high voltage must be applied to the solution to achieve this, resulting in nonlinear behavior at the interface. In our study, we employed mathematical modeling to distinguish the nonlinear effects at the interface from the data obtained from biological solutions. The mathematical model enabled us to investigate the origin of the harmonic differences caused by the presence of cells in the solution, based on the electrochemical processes occurring at the electrode surface. These findings can be applied to studying biological solutions, membrane state, and online monitoring of the growth of yeast colonies on the electrode surface, which requires generating a strong field in the solution and applying high voltage at low frequency.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Woodward, A. M. & Kell, D. B. On harmonic generation in nonlinear biological systems. Biosens. Bioelectron. 10, 639–641 (1995).

Woodward, A. M. & Kell, D. B. Confirmation by using mutant strains that the membrane-bound H+-ATPase is the major source of non-linear dielectricity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 84, 91–96 (1991).

Woodward, A. M., Jones, A., Zhang, X. Z., Rowland, J. & A’, D. B. K. Rapid and non-invasive quantification of metabolic substrates in biological cell suspensions using non-linear dielectric spectroscopy with multivariate calibration and artificial neural networks. Principles and applications. Bicelectrochem. Bioenerget. 40, 99–132 (1996).

Tamura, K., Muraji, M., Tanaka, K. & Shirafuji, T. Generation of nonlinearity in the electrical response of yeast suspensions. Sci. Rep. 12, 3569 (2022).

Tamura, K. et al. Rapid measurement of yeast status using the phase angles of harmonics in the electrical response waveform. IEEJ Trans. Fundamentals Mater. 141, 239–244 (2021).

Tamura, K., Muraji, M., Tanaka, K. & Shirafuji, T. The dependence of nonlinear electrical properties of yeast suspensions on temperature and electrode shape. IEEJ Trans. Fundamentals Mater. 139, 339–344 (2019).

Nawarathna, D. et al. Harmonic generation by yeast cells in response to low-frequency electric fields. Phys. Rev. E - Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 73, 051915 (2006).

Nawarathna, D., Miller, J. H., Claycomb, J. R., Cardenas, G. & Warmflash, D. Harmonic response of cellular membrane pumps to low frequency electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 145 (2005).

Brunauer, G. C., Spadiut, O., Gruber, A. & Slouka, C. Yeast propagation control: low frequency electrochemical impedance spectroscopy as an alternative for cell counting chambers in brewery applications. Chemosensors 8, 27 (2020).

Ruiz, G. A., Zamora, M. L. & Felice, C. J. Isoconductivity method to study adhesion of yeast cells to gold electrode. J. Electr. Bioimpedance. 5, 40–47 (2014).

McAdams, E. T. & Jossinet, J. The detection of the onset of electrode-electrolyte interface impedance nonlinearity: a theoretical study. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 41, 498–500 (1994).

Fasmin, F. & Srinivasan, R. Review—nonlinear electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, H443–H455 (2017).

Murbach, M. D., Hu, V. W. & Schwartz, D. T. Nonlinear electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of Lithium-Ion batteries: experimental approach, analysis, and initial findings. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, A2758–A2765 (2018).

Liebhart, B., Satzke, M., Komsiyska, L. & Endisch, C. Application of nonlinear impedance spectroscopy for the diagnosis of lithium-ion battery cells under various operating conditions. J. Power Sources 480, 485 (2020).

Sharifi, E., Saviz, M. & Faraji-Dana, R. Evaluation of the nonlinear response of KCl solution to High-Amplitude stimulation using a Four-Point cylindrical gold electrode. J. Phys. Chem. B. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.4c02659 (2024).

Treo, E. F. & Felice, C. J. Design and evaluation of a fast fourier transform-based nonlinear dielectric spectrometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 80, 145 (2009).

Alavi, S. M., Mahdi, P., Howey, D. A. & S. J. & Identifiability of generalized Randles circuit models. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 25, 2112–2120 (2016).

Xu, N. & Riley, J. Nonlinear analysis of a classical system: the double-layer capacitor. Electrochem. Commun. 13, 1077–1081 (2011).

Richardot, A. & Mcadams, E. T. Harmonic distortion at the Electrode/electrolyte Interface: a physical interpretation of Schwan’s empirical model (2024).

Richardot, A. & McAdams, E. T. Harmonic analysis of low-frequency bioelectrode behavior. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 21, 604–612 (2002).

Xu, N. & Riley, D. J. Nonlinear analysis of a classical system: the Faradaic process. Electrochim. Acta. 94, 206–213 (2013).

Hubenova, Y. & Mitov, M. Extracellular electron transfer in yeast-based biofuel cells: A review. Bioelectrochemistry 106, 177–185 (2015).

Schaetzle, O., Barrière, F. & Baronian, K. Bacteria and yeasts as catalysts in microbial fuel cells: electron transfer from micro-organisms to electrodes for green electricity. Energy Environ. Sci. 1, 607–620 (2008).

Flores-Cosío, G. et al. Application of dielectric spectroscopy to unravel the physiological state of microorganisms: current State, prospects and limits. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 6101–6113 (2020).

McAdams, E. T. A study of electrode-tissue impedances encountered in cardiac pacing (1987).

Ramos, J., Sychrová, H. & Kschischo, M. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology Yeast Membrane Transport (Springer, 2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elham Sharifi contributed to the writing of the manuscript, conducting experiments, and data analysis. Farshad Darvishi provided yeast samples and guidance for yeast testing. Mehrdad Saviz supervised the project and provided access to laboratory facilities. Reza Faraji-Dana supplied laboratory measurement equipment. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elham, S., Mehrdad, S., Farshad, D. et al. Yeast modifies the nonlinear behavior of the electrode electrolyte interface under high voltage stimulation. Sci Rep 15, 14289 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97947-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97947-8