Abstract

Critical progress in perfecting semiconducting quantum dots’ photoluminescence quantum yield has been made in the past few years. The production of quantum dots with nearly unitary quantum yield has significantly expanded their possible applications, as it is the case of optical refrigeration. We report for the first time optical refrigeration achieved in cadmium selenide/cadmium sulfide (core/shell) structure nanocrystals. Experiments were carried out in colloidal quantum dots suspension, where the excitonic non-radiative decay paths of the quantum dots are effectively suppressed by applying sub-band excitation, eliminating the possible states for energy down-conversion. The cooling effect comes from the significant energy up-conversion observed in the photoluminescence spectra of the samples under sub-band excitation. These results highlight the possibility of realizing temperature control on semiconducting quantum dots through optical approaches, which could provide power cooling mechanism for nano devices and cryogenic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical refrigeration (OR) comprises a set of techniques used to cool down matter by removing its thermal energy through light-matter interactions. A well known application of OR is the laser cooling of an atom or ion gas, where their translational kinetic energy (the major source of their thermal energy) is reduced by Doppler cooling1,2,3,4,5. In the case of solids, where the thermal energy is mainly stored in the form of lattice vibration modes, OR can be realized by utilizing energy up-conversion photoluminescence (UCPL) processes, which was first proposed by Peter Pringsheim in 19296. OR in solids is highly desirable, as it is an essential part of an all-solid-state cryocooler7,8,9. Such device has the advantages of being cryogen and vibration free, leading to intensive research in its experimental realization. The success of OR in solids, however, was mainly accomplished in materials with high optical clarity and purity such as the rare-earth-ion-doped glasses10,11,12,13 and the lead halide perovskites14,15,16. The main reason for OR limitations in solids is primarily associated with the photon escape efficiency (\(\eta _{\text {e}}\)). In OR in solids, thermal energy of the solid is removed by the photons emitted during the UCPL processes. Due to the relatively large size of solids and their typical high refractive index, the emitted photons are much less likely to leave the system due to reabsorption within the material that, when paired with a small but not-zero background absorption, combine to generate heating, negating OR.

Encouragingly, in 2012, Xiong’s group showed that semiconducting nano-materials are potential candidates for OR, where a 40 K cooling in cadmium sulfide (CdS) nanoribbons was observed17. As the typical size of nanomaterials is much smaller than the wavelength of the photons inducing electronic transitions in them, reabsorption and internal reflections become negligible. Simultaneously, nano-semiconducting materials have much larger photon absorption cross section areas comparing to defect centers (rare-earth-ion-doped glasses), leading to a potentially much higher achievable cooling power. Semiconducting QDs attract great interest due to their well known quantum size effect, leading to a tunable and molecular-like absorption spectrum18. Among them, cadmium selenide (CdSe) QDs are popular because their tunable band-gap covers the entire visible spectrum. This allows numerous applications such as QD lasers, solar energy production enhancement and QDs based LED TVs19,20,21. Realizing OR in CdSe QDs can potentially provide self-cooling mechanism in these optical devices, and possibly, passive cooling by the sun light using suitable filters and sample engineering. Here, we report for the first time of the observation of OR on CdSe/CdS (core/shell) structure QDs

Results and discuss

The cooling efficiency, \(\eta _{\text {c}}\) is defined as the cooling power, \(P_{\text {c}}\) over the light input power, \(P_{\text {in}}\) that interacts with the system. According to the work of Sheik-Bahea and Epstein22,

In Eq. (1), \(\eta _{\text {e}}\) describes the probability that an emitted photon leaves the system, \(k_{\text {r}}\) is the radiative decay rate of excitons in the system, and \(\varepsilon\) is the energy. Both \(\eta _{\text {e}}\) and \(k_{\text {r}}\) are functions of \(\varepsilon\), excitation energy \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\), temperature T and \(P_{\text {in}}\). With proper design of the system, \(\eta _{\text {e}}\) might be considered constant throughout the whole emission spectrum. Using that the mean emission energy \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) is defined as

and introducing the total radiative decay rate \(K_{\text {r}}=\int _{0}^{\infty }k_{\text {r}}d\varepsilon\), Eq. (1) can be rewritten as,

\(P_{\text {in}}\) is defined as the total energy absorbed by the system,

In Eq. (3), a and \(a_{\text {b}}\) denote the absorption rates of the cooling substance (QDs in our case) and the background respectively, and are functions of \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\) and T. In steady state, \(\eta _{\text {e}}K_{\text {r}}+K_{\text {nr}}=a\), where \(K_{\text {nr}}\) denotes the non-radiative decay rate of excitons. Thus, \(\eta _{\text {c}}\) is obtained by dividing Eq. (2) over Eq. (3),

where \(\eta _{\text {ex}}=\frac{\eta _{\text {e}}K_{\text {r}}}{\eta _{\text {e}}K_{\text {r}}+K_{\text {nr}}}\) is defined as the external quantum efficiency. Thus, in a QDs system with quantum yield \(\eta\) approaching unity (\(K_{\text {nr}}\rightarrow 0\)), \(\eta _{\text {ex}}\simeq \eta \rightarrow 1\). Therefore,

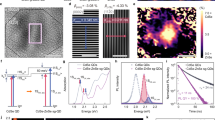

In order to achieve net cooling, \(\eta _{\text {c}}\) must be positive. Because \(\eta\) has a maximum value of 1, having \(\frac{\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}}{\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}}>1\) is critical for realizing OR (since the temperature change in our experiment was \(<1\) K, these variables, except \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\), are treated as temperature independent). In CdSe QDs systems this condition can be satisfied by carefully exciting them with specific energy determined by their PL properties. Shown in Fig. 1a are a typical absorption spectrum (red curve) together with a high energy excitation (\(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\) is much larger than the absorption edge of the QDs) PL (HPL) spectrum (blue curve) of the QDs samples to reveal possible radiative decay paths. A red-shift of the HPL spectrum from the absorption edge was observed, which is a well documented property of QDs, related to the phonon-assisted processes and surface associated emission23. As shown in Fig. 1b, a possible way to create the UCPL in such system is through the transitions between the QDs’ valence band and the shallow electron surface states (ESST) (in our particular samples, hole traps and deep electron traps were very unlikely to exist)24,25,26,27.

(a) Typical absorption spectrum (red curve) and HPL spectrum (blue curve) of QDs samples with its core size of \(\sim 3.3\) nm and a shell thickness of about 1.4 nm. Gray area denotes the range of excitation energies that could possibly generate net energy up-conversion in PL spectra. (b) Schematic of PL processes with sub-band absorption, where \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\) is less than the \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) of the HPL spectrum.

The energy up-conversion is achieved during the thermalization processes of the exciton inside the surface states27.

PL spectra of a sample with core radius \(\sim 3.3\) nm with 4 monolayers (ML) of CdS shell, at sub-band excitation: (a) Typical UCPL spectrum with \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}=1.946\) eV. (b) \(\eta _{\text {c}}(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}})\) from Eq. (4) with \(a_{\text {b}}/a=300\) ppm and \(\eta =0.998\).

Another mechanism which could possibly generate UCPL in QDs is multi-photon absorption, this mechanism must be excluded from our experiment, because of its net heating effect. Our methods was to limit the excitation power, such that under experimental conditions, the exciton density was much smaller than 1. Data are shown in Fig. 2a, where the laser signal was suppressed significantly by using an off-axis collecting system developed in our previous work27. According to the data, when \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\) is much lower than the QDs’ HPL peak energy, UCPL was dominant. As listed in Table 1, the mean up-conversion energy (MUE) (\(\Delta \bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}} = \bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}-{\varepsilon }_{\text {ex}}\)) increased almost linearly as the excitation energy was reduced, which value increased from 23 to 36 meV as \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\) decreased from 1.957 to 1.929 eV. Because the size of QDs (\(\sim 6\) nm) is close to the excitonic Bohr-radius of CdSe, both longitudinal optical phonons (LOPs) of CdSe (\(\sim 26\) meV28,29) and CdS (\(\sim 37\) meV17) might be involved in the UCPL processes. Therefore, one possible explanation of this observation could be that the dominant processes at sub-band excitation are single-LOP-annihilation coupled PL processes. As the excitation energy is further decreased from the absorption edge, the contribution from LOPs of CdS shell becomes more and more significant. When \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}\) is much lower than the absorption edge (\({\sim }\,140\) meV lower for the sample showed in Table 1), a much rapid increase in the MUE was observed, indicating the existence of multi-phonon absorption. Although such observation suggests a larger \(\frac{\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}}{\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}}\) value, a diminishes rapidly, yielding a much smaller, or even negative value for \(\eta _{\text {c}}\), precluding OR. One unexplained observation is that the maximum observable energy up-conversion in PL spectra was found to be \(\sim 210\) meV for all tested sub-excitation energies. \(\eta _{\text {c}}(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}})\) was calculated with Eq. (4) (\(a_{\text {b}}=300\) ppm, \(\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}=1.946\) eV and \(\eta =0.998\) were used to calculate the result shown in Fig. 2b), while the mean emission energy was estimated with the model developed by our group earlier27), indicating the possibility of having a positive \(\eta _{\text {c}}\) value at sub-band excitation and the existence of the local maximum of \(\eta _{\text {c}}\)

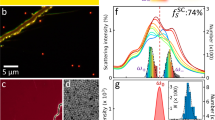

The cooling effect due to UCPL was determined by measuring the temperature change in the sample. It was measured with an optical thermometer (shown in Fig. 3a), whose design is very similar to the pump-probe thermometry technique17. The optical thermometer is based on the temperature dependent energy band-gap of semiconductors. In the case of CdSe QDs, the energy band-gap monotonically decreases as the temperature increases in the range of 80–300 K with typical declining rate of 350–440 \(\upmu \text {eV/K}\), leading to a similar change in the HPL emission energy30. Because at room temperature the HPL spectra of CdSe/CdS QDs is quite broad (typical FWHM of our sample is 85 meV) compared to the band gap change over 1 K, instead of determining the energy of the PL maximum, we used the calculated \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) as the measured quantity. To further increase the precision, each temperature measurement contained five consecutive exposures (\(\tau _{\text {s}}=3\) s between two consecutive exposures due to the data acquisition time limited by the computer system), such that, one complete temperature measurement takes 13.7 s. Hence, the temperature was determined by the mean value of the five measurements and the standard error of the mean was used for the measurement uncertainty. As shown in Fig. 3b, the probe laser and the pump laser were introduced through the same light path by using a beam splitter. The exposure sequence is shown in Fig. 3c. Experimental details are described in the “Methods” section.

Optical thermometry setup and the time sequence of pump and probe: (a) CAD model of the sample holder inside the cryostat(the 3D model was generated with software AutoCAD 2018, www.autodesk.com). (b) Experimental setup of the pump and probe lasers. (c) Pump and probe lasers on and off time sequence controlled by the chopper. \(\tau _{\text {c}}\) denotes the duration of the pump laser, \(\tau _{\text {p}}\) denotes the duration for the probe laser and \(\tau _{\text {s}}\) denotes the data acquisition time of the system for each exposure.

The calibration of our system was carried out by using an argon laser with its major emission peak at 2.41 eV as the HPL excitation source (defined as the probe laser). As shown in Fig. 4a, when the temperature in the cryostat was increased from 296 to 300 K, \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) HPL decreased monotonically at an average declining rate of \(360\,\upmu \text {eV/K}\). However, HPL processes always create heating effects due to phonon emission. On the other hand, the resolution of this technique is highly determined by the HPL intensity, since the noise induced by cosmic radiation and dark current of the detector of the spectrometer are fixed. The higher the HPL intensity, the better the resolution of the optical thermometer would be. To balance the trade off between heating effects and resolution of the thermometer, evaluation of the HPL’s heating effect was carried out, where the power of the argon laser was set to be \(\sim 10\,\upmu \text {W}\) with an exposure length \(\tau _{\text {p}}=0.3\) s.

Calibration results of the optical thermometer: (a) Typcial \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) of the QDs samples within a temperature range of \(296\sim 300\) K, (b) Heating effect from probe laser with \(10\,\upmu \text {W}\) power, \(\tau _{\text {c}}=10\) s/30 s (top/bottom panels) and \(\tau _{\text {p}}=0.3\) s (pump laser was blocked during this time).

According to the data shown in Fig. 4b, without applying the pump laser, a limited heating effect was observed when \(\tau _{\text {c}}=10\) s, and becomes less distinguishable by extending \(\tau _{\text {c}}\) to 30 s with a typical accuracy of \(45\,\upmu \text {eV}\) (equivalent to 0.11 K). Therefore, the probing configuration \(\tau _{\text {c}}=30\) s was applied in the OR experiment.

A diode laser with an excitation energy of 1.941 eV and power of 1.5 mW was used as the pump laser in the OR experiment. The sample’s \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) is monitored and its value associated to a temperature following Fig. 4a.

OR experimental result: (a) Direct measurement of the sample’s \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) during the OR experiment. The green arrow indicates when the pump laser was unbocked after the fourth temperature mesurement. The red curve indicates when it was subsequently blocked. The cooling curve (blue) and the recovery curve (red) are calculated with the same \(\tau =180\) s.(b) Change in the \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) of the sample corresponding to an increase in the cryostat’s temperature after the 7th temperature measurement. The red curve is the fitting result of exponential decay with \(\tau _{\text {h}}=180\) s.

The main results are shown in Fig. 5a, obtained on a sample with a core size of 3.3 nm covered by a shell made of 4 ML of CdS. During the experiment, the pump laser was blocked until the fourth optical thermometry was done (pointed by the green arrow in Fig. 5a). The pump laser was unblocked right after that and an increase of the HPL’s \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) was observed, started to saturate, and stabilized after an increase of \(({\sim }\,140\pm 32)\,\upmu \text {eV}\). After the 20th temperature measurement the pump laser was blocked (pointed by the red arrow in Fig. 5a), HPL’s \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) began to decrease gradually back to the original value (\({\sim }\,2.015\,\upmu \text {eV}\) at 296.1 K). According to the calibration results shown in Fig. 4a, a temperature difference of \(-0.37\pm 0.08\) K was established by OR, showing a net cooling effect of the system. A comparison measurement obtained by heating up the cryostat is shown in Fig. 5b, where the temperature of the cryostat was increased by 0.5 K (the cryostat’s temperature stabilized within 30 s), and the mean emission energy changed following a similar trend, well fitted by an exponential curve with the same time constant (180 s) used for the OR results. A possible alternative explanation to the observed cooling effect would be the laser modified the QDs during illumination, such as detaching the ligands from the QDs. It could lead to similar observation. However, since such processes are typically irreversible, the authors concluded that it is very unlikely that the observed mean emission energy change was due to photon chemical reaction caused by the laser excitation.

The net cooling effect can be calculated, and in steady state, \(P_{\text {c}}\) needs to equal the net heat flow \(P_{\text {h}}(T)\) from the environment. The equilibrium temperature \(T_{\text {f}}\) is reached when \(P_{\text {c}}=P_{\text {h}}(T_{\text {f}})\). \(P_{\text {c}}\) is optimized with unity QY and neglecting background absorption. Within such assumptions, the maximum cooling power \(P_{\text {c,max}}\) is given by

\(P_{\text {ex}}\) denotes the excitation power, which was set to be 1.5 mW. The absorption rate \(a\approx 0.34\) was obtained from the absorbance data of the sample, leading to a maximum cooling power of \(8.1\,\upmu \text {W}\). On the other hand, possible heating sources include thermal conduction from remnant air in the vacuum chamber, heat conduction though the support, heat transfer due to thermal radiation and background absorption by the glass capillary with the solvent. At a working pressure of less than \(7.4\times 10^{-6}\) mbar, heat flow due to gas conduction is negligible (\({\sim }\,10^{-8}\) W at \(\Delta T=10\) K). The background absorption from the glass capillary and the solvent are also negligible. The system was designed to isolate the sample from the environment as much as possible, therefore, the structures were built in such a way that all the parts just seated on each other (no grease was applied to contact points), leading to a poor thermal conductivity with unclear temperature gradient. It also leads to difficulties in calculating the heat transfer through thermal radiation. Since the temperature difference created by the OR was small, it is reasonable to assume \(P_{\text {h}}\propto \Delta T\), and

with \(C_{\text {p}}\) the effective heat capacitance of the sample, H is the proportionality between \(P_{\text {h}}\) and \(\Delta T\), and \(T_{0}\) denotes the environment temperature. Therefore, the temperature of the system should follow a single exponential decay curve,

with the same characteristic time, \(\tau _{\text {h}}=\frac{C_{\text {p}}}{H}\) for both heating and cooling processes. Since Eq. (6) should be valid independently of the source for \(P_{\text {c}}\) a test of the model was carried out by monitoring the \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) of our sample after heating up the substrate over a time much shorter than the time between temperature measurements, as shown in Fig. 5b. The data is well described by a single exponential curve with \(\tau _{\text {h}}=180\) s, which is the same value used in our OR experiments (the curves in Fig. 5a, are single exponential functions with characteristic time \(\tau =\tau _{\text {h}}\)). The sample contains approximately \(20\,\upmu \text {g}\) QDs which were suspended in \(2.36\,\upmu \text {L}\) (about 2.5 mg) solvent. Hence, \(C_{\text {p}}\) of the sample is dominanted by the solvent (volume percent, octadecene \(\sim \,46\%\), dodecane \(\sim \,14\%\), oleylamine \(\sim \,36\%\) and octylamine \(\sim \,4\%\)), and the glass wall around the sample section with \(C_{\text {p}}\simeq 9\times 10^{-3}\) J/K. An estimate of the temperature drop can be made with \(\Delta T\approx P_{\text {c}}\tau _{\text {h}}/C_{\text {p}}=\frac{P_{\text {c}}}{H}=0.17\) K, which is close to our observation. The authors have to point out that, since \(\tau _{\text {h}}\) is linearly dependent on the value of \(C_{\text {p}}\), the change in the \(C_{\text {p}}\) will directly be reflected on this value, which is confirmed by our experimental result (shown in SI). On the other hand, \(\Delta \text {T}\)ΔT is solely dependent on \(\frac{P_{\text {c}}}{H}\), which is only related to the thermal isolation condition. Limited by our setup, the maximum cooling effect observed was a temperature drop of (\(0.37\pm 0.08\)) K. Our data suggests, however, a great potential for OR in CdSe QDs. In our experiment, the actual amount of QDs involved in the cooling processes are of the order of \(10^{-15}\) mol. Considering the energy removed per dot per photon absorbed is given by \(\varepsilon _{\text {em}}-\varepsilon _{\text {ex}}=0.031\) eV (according the UCPL spectrum, typical \(\varepsilon _{\text {em}}=1.971\) eV). If the cooling efficiency remains the same after scaling the system up and assuming the mean excitation rate of QDs is 100 kHz, a theoretical expectation of 1 W cooling power could be accessible with only nmols of QDs One possible problem in further improving the OR effect in QDs systems would be finding the proper dielectric environment. Colloidal QDs are stable when dispersed inside organic solvents with protection from ligands. The physical properties of this organic compounds restrict the application of QDs at this stage, for instance, typical freezing point of long chain organic solvents is close to room temperature. Generally speaking, maintaining a stable dielectric shielding environment that can retain the QDs’ unitary QY would be the key factor limiting their optical cooling efficiency and possible applications, as the liquid environment for the colloidal suspension is not compatible to any solid state system. Therefore, finding a transparent dielectric coating materials that can retain the optical properties of CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs is paramount for using them as cooling agents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, OR experiments in CdSe/CdS QDs system have been carried out. This is the first time that OR has been achieved on CdSe based QDs, where significant UCPL was observed and considered as the cooling mechanism during the experiment. The temperature of the sample was measured by monitoring \(\bar{\varepsilon }_{\text {em}}\) of the QDs sample, effectively obtaining an optical thermometer. A net temperature drop of (\(0.37\pm 0.08\)) K was observed, indicating a potential cooling power \(\sim\) 1 Watt could be achievable by using \(10^{14}\) dots. Although our work is still in the early stages of demonstrating the concept of laser cooling in colloidal semiconductors, its future looks promising. Optimizing thermal isolation and excitation methods, as demonstrated by Xiong’s group with CdS nanoribbons-where a temperature drop of over 40K was achieved under laser excitation-could significantly enhance its potential.

Methods

QDs synthesis

The method of the QDs synthesis was based on the report from Peng’s group31,32, where small adjustments were made to account for the different setups. The growth of the shell was carried out using a single precursor (cadmium diethyldithiocarbamate) method. The surface of the core/shell dots was finished with cadmium formate to further reduce possible surface defects.

Chemicals used in the synthesis: cadmium oxide (CdO, 99.999%, Strem Chemicals), myristic acid (MA, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich), 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%, Sigma-Aldirch), selenium dioxide (\(\text {SeO}_{2}\), 99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich), oleic acid (90%, Sigma-Aldrich), oleylamine (OAM, 70%, Sigma-Aldrich), octylamine, (98%, Sigma-Aldrich), methanol (99.5%,Sigma-Aldrich), acetone (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich), hexane anhydrous (95%, Sigma-Aldrich), cadmium diethyldithiocarbamate (\(\text {Cd(DDTC)}_{2}\), 96%, Gelest), cadmium formate (CdFt, 98%, Gelest), dodecane (98%, Sigma-Aldrich), tributylphosphine (TBP, 95%, Sigma-Aldrich)

All of the chemicals were degassed before use and the synthesis was performed in an inert gas (argon) atmosphere.

Synthesis of CdSe core

The procedure for synthesizing CdSe cores is well documented by the Alivisatos group33, where cadmium myristate and \(\text {SeO}_{2}\) were used as precursors of the CdSe cores.

The cadmium myristate was synthesized in our laboratory. 13 mg CdO and 46 mg myristic acid were mixed and dissolved in 5 mL octadecene in a 50 mL flask. The mixture was then heated to \(250\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) with vigorous stirring until the whole mixture turned pale yellow (cadmium myristate solvent). After that, 11 mg \(\text {SeO}_{2}\)34 were added into the flask. The reaction of forming quantum dots started at a temperature around \(220\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) while stirring, accompanied by a change in the color of the mixture from yellow to red. At this moment, 0.1 mL oleic acid was injected at a rate of 10 \(\upmu \text {L}\) every 10 s to slow down the reaction speed35. After injection, the temperature was maintained for another 20 min (the size of the dots can be adjusted by tuning the length of the reaction time), heat was removed and the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature.

Core cleaning process

An in-situ cleaning procedure was applied before starting the shell growth procedure. The core suspension was heated to \(50\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\). Then 0.2 mL TBP and 0.2 mL octylamine was added into the solution to remove ligands attached on the surface of the CdSe cores. 4 mL anhydrous hexane and 6 mL anhydrous methanol were added to remove the TBP, octylamine and all other byproducts generated in the core synthesis. The mixture formed an upper red layer of octadecene with CdSe cores and a bottom clear layer of methanol with byproducts. After removing the bottom layer, 4 mL anhydrous hexane and 6 mL anhydrous methanol were added again to remove the added chemicals. The cleaning process was repeated once more to ensure the complete removal of the unreacted precursors and the by products. Then, to remove the hexane left in the suspension, vacuum (\({\sim }\,80\) mbar) was applied for 10 min. Finally, heat was removed and the suspension was allowed to cool to room temperature.

Growth of the CdS shell

Before starting the shell growth, 0.1 mL core suspension were extracted from the flask for absorption spectroscopy. The size and the concentration information of the CdSe cores were derived from the empirical formula36

Here d denotes the core diameter, \(\beta\) denotes the molar attenuation coefficient.

After determining the concentration and the size of the CdSe cores, 5 mL dodecane and OAM mixture (molar ratio 1:1) was loaded into the flask. While stirring, the temperature was raised to \(80\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\), followed by injecting \(\text {Cd(DDTC)}_{2}\) solution (0.15 M, dissolved in dodecane and OAM mixture with a 1:1 volume ratio), sufficient for the growth of a monolayer of CdS. The temperature was maintained for another 5 min to allow for the precursor to be adsorbed on the CdSe cores. Then, the solution was heated to \(150\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) to initiate the shell growth process and continued for 20 min. Such adsorb-growth procedure was repeated several times until the desired thickness of CdS shell (4 monolayers for our samples) was achieved. The specific amount of the precursor was estimated with the method described in Chen’s report37. The typical amount for our synthesis was 0.05 mL. 0.07 mL, 0.12 mL, 0.15 mL and 0.20 mL for the first, second, third and fourth monolayer respectively. Argon purging at \(80\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) (higher temperatures were found to be harmful to the QY of the sample) was used on the suspension after completing the shell growth. Finally, a small amount of CdFt solution (0.15 M, dissolved in octylamine) was added, heated to \(50\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) for 15 min to form a mono-\(\text {Cd}^{2+}\) layer on the surface of the CdS shell to remove deep hole trapping states at the shell surface.

Characterizations of QDs samples

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

A Bruker D-8 Discover A-25 XRD system was used for the measurement. QDs samples were cleaned twice with methanol before XRD measurements to remove capping ligands, reducing the background noise. After cleaning, the sample was first transferred into hexane, then deposited onto a piece of (100) silicon wafer. To get enough signal from the QDs sample, multiple depositions were performed, followed by air-drying to create a thick (hundreds of \(\upmu \text {m}\)) layer of stacked QDs. The scanning rate was chosen to be 0.5–1 s per \(0.02\,^{\circ }\) in \(2\theta\). The power of the X-ray beam was set to be 50,000 W.

Absorption spectroscopy

Absorption spectra of the QDs samples were taken by using Thermal Scientific Evolution 600 UV-Vis spectrometer. Quartz cuvettes with 1 cm optical path were used as sample holders. The base absorption line was derived by testing the cuvettes with solvent only. After that, proper amount of the QDs suspension was added into the same cuvette to make the maximum absorbance in the range of \(1.5\sim 3\) (a machine error occurs when absorbance is higher than 3). The light source of the spectrometer is a built-in xenon lamp. The scanning light was sent through the built-in monochromator to generate a 2 nm bandwidth beam. The spectral resolution was chosen to be 0.1 nm at a scanning rate of 60 nm per min.

PL spectroscopy

Jobin Yvon Horiba Triax-550 spectrometer equipped with a CCD camera (Jobin Yvon Horiba CCD-3000) was used to acquire the PL spectra of our samples. The CCD camera has a sensor array of 2000 (energy axis) \(\times 800\) (intensity axis) pixels and works at \(\sim 149\) K using liquid nitrogen cooling, achieving a dark current rate of 3 electrons per second per pixel, while the readout noise is 4–10 electrons per second per pixel. When working with a grating density of 300 lines/mm, the effective resolution of the system is 0.091 nm. Sample were loaded in a glass capillary (1 mm inner diameter and 1.5 outer diameter) sealed by super glue at both ends. Capillaries used in our experiment were cut to around 20 mm and the sample section was about \(\sim 2.5\) mm long. When taking PL spectra, the capillary was placed in the Janis ST-500 cryostat, under vacuum(\(< 1\times 10^{-5}\) mbar). As shown in Fig. 3c, the excitation light was sent through the bottom window and reflected by a small mirror mounted inside the cryostat to reach the sample horizontally, while the collecting objective with a working distance of 10.6 mm and a numerical aperture of 0.5 was aligned perpendicularly to the capillary above the top window (5.3 mm above the capillary).

When running sub-band excitation experiments, the laser energy lies inside the PL spectrum. Although the off-axis collecting system (collecting direction was perpendicular to the excitation beam) described in section “PL spectroscopy' helped reduce scattered light from the excitation beam, due to the low absorption efficiency (\(<\,2\%\) of the first absorption maximum of the sample) at sub-band excitation, scattered excitation light appeared to be dominant in the PL spectra. Our solution was to add a set of polarizers to the system. In our setup, one of the polarizers was placed right before the focusing lens to generate a horizontally polarized beam, while the laser was oriented in the same way to minimize the intensity lost. The other polarizer was placed right above the collecting objective with its direction perpendicular to the polarization of the excitation beam, to minimize the amount of scattered light (the extinction rate was found to be 1:50) into the spectrometer.

Radiative decay lifetime test

The PL lifetime of the QDs samples was measured by applying a time-resolved PL measurement. A Horiba Delta Pro Fluorescent Lifetime system was used to perform such measurement. The system works with a built-in Horiba 405nm Delta Diode as the excitation light source, generating as short as 15 ps pulse. Silica particles with an average size of 40 nm suspended in toluene were used to derive the instrumental response function (IRF) of the system. All test samples were placed in quartz cuvettes. The concentration of the sample was controlled (diluted in toluene) to give an absorbance value of less than 0.138 to make re-absorption negligible.

Temperature dependent HPL spectroscopy

A Janis research CO., INC. ST-500 cryostat was used as the container for the temperature dependent HPL test. It is equipped with a NTC (negative thermistor), a built-in heater (maximum power of 5 W) and a cryogen transfer hose. The temperature was monitored and controlled by a LakeShore 331 Temperature Controller. To minimize the temperature gradient between the sample and the cold finger, modifications in the substrate to optimize the thermal conductivity were introduced. First, a copper disc designed to fit the cold finger slot (25.4 mm in diameter) was used as the substrate to create a uniform temperature surface. At the center of the copper disc, a 1 mm diameter hole was drilled allowing the excitation light to go through. On the other hand, it is well known that the dielectric environment changes the PL properties of QDs dramatically. To optimize thermal conduction, Apiezon type N grease was uniformly spread onto the copper disc before placing the capillary onto it. The capillary was placed in a way such that the sample section was right above the copper disk hole. Argon laser with major emission peak at 514 nm was used as the excitation source.

At each measurement, the temperature of the cold finger was set to a given value, for example 296 K, and the system was allowed to stabilize for 1 h to guarantee thermal equilibrium between the sample and the cryostat. Then 10 consecutive HPL spectra (1 s exposure) were taken with argon laser excitation (power of the argon laser was measured to be \(\sim 10.6\,\upmu W\)). Heating effect of HPL was negligible in this experiment, since the sample was well thermally coupled to the environment. For a given measurement, since the configuration of the spectrometer was fixed, the uncertainty of temperature change contributed by the instrument was defined by the minimum drive step size, (0.002 nm, less than \(7\,\upmu \text {eV}\) at 600 nm) which is negligible compared to the statistical error. Therefore, when combining the errors, it was dominated by the statistic error, and the standard error of the mean was applied as the temperature measurement uncertainty.

Measurement of quantum yield

A relative method was applied, where the quantum yields of the samples were obtained by comparing them with a standard dye solution that has a known quantum yield. In particular in our experiment, Rhodamine 110 was used as the reference dye. The dye solution was dissolved and diluted in 70% ethanol water solution, while the QDs suspension were diluted with hexane. During a typical quantum yield measurement, the absorbance and PL spectra of the reference dye and QD suspensions were taken at different concentrations, while the maximum absorbance was maintained below 0.15 to suppress re-absorption, achieving a good linear response between absorption and PL intensity. By plotting the reference dye and QD suspension’s PL intensities versus their absorption, the QDs’ quantum yield is obtained through the equation: \(\eta =\frac{k_{\text {ref}}}{k_{\text {q}}}\frac{n_{\text {q}}}{n_{\text {ref}}}\eta _{\text {ref}}\), where \(k_{\text {ref}}\) and \(k_{\text {q}}\) denote the slopes of the PL intensity versus absorption plots of the reference dye and QDs sample respectively. \(\eta _{\text {ref}}\) is the quantum yield of the reference dye.

OR experiment

The OR test were designed as two parts, one is cooling the sample by introducing sub-band excitation, the other one is measuring the temperature of the sample using the optical thermometer (monitoring the HPL spectra of the sample). Experiments were done in the Janis research CO., INC. ST-500 cryostat (pressure lower than \(10^{-5}\) mbar) to provide enough thermal isolation to maximize the cooling effect. A laser diode working in the sub-band excitation energy range (from 1.89 to 1.943 eV) and an argon laser were used as the cooling pump sources and the temperature probe respectively. To thermally isolate the sample from the environment, two supports made of expanded-polystyrene foam with \(2\,\text {mm}\times 3\,\text {mm}\times 4\,\text {mm}\) (width\(\times\)depth\(\times\)height) in dimensions were placed on the anodized aluminum substrate as spacers.

As shown in Fig. 6, the diode laser and the argon laser were sent into the cryostat through the same light path by using a beam spliter. Before the beam spliter, a chopper was programed to sequentially block one of the lasers and allow the other one to pass, following the pattern shown in Fig. 3b. The typical power of the pump laser reaching the sample was 1.5 mW, while the power of the probe laser was always less than \(10\,\upmu \text {W}\).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Phillips, W. D. Nobel lecture: Laser cooling and trapping of neutral atoms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 721–741. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.70.721 (1998).

Levi, B. G. Cornell, Ketterle, and Wieman share Nobel prize for Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys. Today 54(12), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1445529 (2001).

Truppe, S. et al. Molecules cooled below the doppler limit. Nat. Phys. 13(12), 1173–1176. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4241 (2017).

Pan, D., Xu, H. & de Abajo, F. J. G. Rotational doppler cooling and heating. Sci. Adv. 7(2), eabd6705. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd6705 (2021).

Lyne, J., Bassler, N. S., Park, S., Pupillo, G. & Genes, C. Purcell-modified doppler cooling of quantum emitters inside optical cavities. Phys. Rev. A 110, 013115. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.110.013115 (2024).

Pringsheim, P. Zwei bemerkungen fiber den untersehied yon lumineszenz- und temperaturstrahlung. Z. Phys. 57, 739–746 (1929).

Edwards, B. C., Buchwald, M. I. & Epstein, R. I. Development of the Los Alamos solid-state optical refrigerator. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 69(5), 2050–2055. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1148897 (1998).

Edwards, B. C., Anderson, J. E., Epstein, R. I., Mills, G. L. & Mord, A. J. Demonstration of a solid-state optical cooler: an approach to cryogenic refrigeration. J. Appl. Phys. 86(11), 6489–6493. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.371713 (1999).

Hehlen, M. P. et al. First demonstration of an all-solid-state optical cryocooler. Light Sci. Appl. 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-018-0028-7 (2018).

Epstein, R. I., Bucwald, M. I., Edwards, B. C., Gosnell, T. R. & Mungan, C. E. Observation of laser-induced fluorescent cooling of a solid. Nature 377, 500–503. https://doi.org/10.1038/377500a0 (1995).

Seletskiy, S. D. et al. Laser cooling of solids to cryogenic temperatures. Nat. Photonics 4, 161. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2009.269 (2010).

Nemova, G. & Kashyap, R. Alternative technique for laser cooling with superradiance. Phys. Rev. A 83, 013404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.83.013404 (2011).

Rudyi, S. S. et al. Deep laser cooling of rare-earth-doped nanocrystals in a radio-frequency trap. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 34(12), 2441–2445. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.34.002441 (2017).

Ha, S. T., Shen, C., Zhang, J. & Xiong, Q. Laser cooling of organic–inorganic lead halide perovskites. Nat. Photonics 10, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2015.243 (2015).

Tonkaev, P., Zograf, G. & Makarov, S. Optical cooling of lead halide perovskite nanoparticles enhanced by mie resonances. Nanoscale 11, 17800–17806. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NR03793D (2019).

Roman, B. J., Villegas, N. M., Lytle, K. & Sheldon, M. Optically cooling cesium lead tribromide nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 20(12), 8874–8879. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03910 (2020) (PMID: 33196199).

Zhang, J., Li, D., Chen, R. & Xiong, Q. Laser cooling of a semiconductor by 40 kelvin. Nat. Lett. 493, 504–508. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11721 (2012).

Norris, D. J. Nanocrystal Quantum Dots 2nd edn (CRC Press, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420079272.

Klimov, V. I. et al. Optical gain and stimulated emission in nanocrystal quantum dots. Science 290, 314–317. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5490.314 (2000).

Azmi, R., Oh, S. & Jang, S. High-efficiency colloidal quantum dot photovoltaic devices using chemically modified heterojunctions. ACS Energy Lett. 1(1), 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00070 (2016).

Zan, L., Lin, D., Zhong, P. & He, G. Optimal spectra of white led integrated with quantum dots for mesopic vision. Opt. Express 24(7), 7643–7653. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.007643 (2016).

Sheik-Bahae, M. & Epstein, R. I. Optical refrigeration. Nat. Photonics 1, 693. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2007.244 (2007).

Gao, Y. & Peng, X. Photogenerated excitons in plain core cdse nanocrystals with unity radiative decay in single channel: the effects of surface and ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137(12), 4230–4235. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b01314 (2015).

Rusakov, K. I. et al. Control of efficiency of photon energy up-conversion in CdSe/ZnS quantum dots. Opt. Spectrosc. 94, 859–863. https://doi.org/10.1134/1.1586736 (2003).

Wang, X. et al. Photoluminescence upconversion in colloidal CdTe quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 68, 125318. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.68.125318 (2003).

Voznyy, O. Mobile surface traps in cdse nanocrystals with carboxylic acid ligands. J. Phys. Chem. C 115(32), 15927–15932. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp205784g (2011).

Hua, M. & Decca, R. S. Net energy up-conversion processes in cdse/cds (core/shell) quantum dots: A possible pathway towards optical cooling. Phys. Rev. B 106, 085421. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.085421 (2022).

Alivisatos, A. P., Harris, T. D., Carroll, P. J., Steigerwald, M. L. & Brus, L. E. Electron-vibration coupling in semiconductor clusters studied by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 90(7), 3463–3468. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.455855 (1989).

Mittleman, D. M. et al. Quantum size dependence of femtosecond electronic dephasing and vibrational dynamics in cdse nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14435–14447. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.49.14435 (1994).

Jing, P. et al. Temperature-dependent photoluminescence of cdse-core cds/cdzns/zns-multishell quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. C 113(31), 13545–13550. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp902080p (2009).

Nan, W. et al. Crystal structure control of zinc-blende CdSe/CdS core/shell nanocrystals: Synthesis and structure-dependent optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134(48), 19685–19693. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja306651x (2012).

Pu, C. & Peng, X. To battle surface traps on CdSe/CdS core/shell nanocrystals: Shell isolation versus surface treatment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(26), 8134–8142. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b02909 (2016).

Manthiram, K., Beberwyck, B. J., Talapin, D. V. & Alivisatos, A. P. Seeded synthesis of CdSe/CdS rod and tetrapod nanocrystals. J. Vis. Exp. 82, e50731. https://doi.org/10.3791/50731 (2013).

Chen, O. et al. Synthesis of metal-selenide nanocrystals using selenium dioxide as the selenium precursor. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 47(45), 8638–8641. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200804266 (2008).

Yang, Y. A., Wu, H., Williams, K. R. & Cao, Y. C. Synthesis of CdSe and CdTe nanocrystals without precursor injection. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 44(41), 6712–6715. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200502279 (2005).

Karel Čapek, R. et al. Optical properties of zincblende cadmium selenide quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. C 114(14), 6371–6376. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp1001989 (2010).

Chen, D., Zhao, F., Qi, H., Rutherford, M. & Peng, X. Bright and stable purple/blue emitting cds/zns core/shell nanocrystals grown by thermal cycling using a single-source precursor. Chem. Mater. 22(4), 1437–1444. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm902516f (2010).

Würth, C., Grabolle, M., Pauli, J., Spieles, M. & Resch-Genger, U. Relative and absolute determination of fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1535. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.087 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Indiana University Integrated Nanosystems Development Institute (INDI), and National Science Foundation Grant NSF PHY-1607360.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and R.S.D. developed the idea of the research. M.H. prepared the samples and performed the experiment. M.H. and R.S.D. performed data analysis. M.H. and R.S.D. wrote the main manuscript text. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hua, M., Decca, R.S. Optical refrigeration on cadmium selenide/cadmium sulfide quantum dots. Sci Rep 15, 13286 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97958-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97958-5