Abstract

The overactive bladder (OAB) is associated with obesity and inflammation. The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) has emerged as a novel and more accurate measure of obesity compared to traditional indices, while the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) quantifies the inflammatory potential of one’s diet. However, the relationship between WWI, DII, and OAB remains unclear. This study aims to elucidate the association between WWI and OAB and to determine whether this relationship is mediated by dietary inflammation. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2005 and 2018, comprising 10,176 participants, were analyzed in this study. The association between WWI and OAB was examined using multivariate logistic regression models, smooth curve fitting, and subgroup analysis. Furthermore, the predictive capabilities of various anthropometric indices—including WWI, body roundness index (BRI), body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, body fat percentage (BF%), and weight—on OAB incidence were assessed using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Finally, a mediation analysis was conducted to explore whether the DII mediates the relationship between WWI and OAB. There was a significant positive association between WWI and OAB. After adjusting for covariates, for each unit increase in WWI, there was a 40% increase in the prevalence of OAB (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.25–1.58, P < 0.001). This positive correlation persisted when WWI was categorized into quartiles. The dose–response curve showed a significant linear positive correlation between WWI and OAB. The correlation between WWI and OAB persisted in subgroup analysis. The ROC curve analysis revealed that WWI had a superior predictive capability compared to traditional obesity indices, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.661 (95% CI 0.648–0.674, all P < 0.001). The results of the mediation analysis showed that 5.02% of the association between WWI and OAB was mediated by DII (P = 0.016). Our findings suggest that individuals with higher WWI may have an increased risk of OAB. Additionally, an anti-inflammatory diet may be beneficial in preventing OAB. Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot establish a causal relationship. Future longitudinal studies are needed to validate this association and investigate the potential biological mechanisms underlying this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a chronic condition associated with urinary dysfunction that significantly impairs patients’ quality of life and is very common in daily life. The concept was officially proposed by the International Continence Society (ICS) in 2002 to highlight storage symptoms of the lower urinary tract. OAB is classified as a symptom syndrome of lower urinary tract dysfunction, characterized by urgency and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), along with frequency and nocturia. The epidemiology of OAB varies widely across different regions of the world, often confused with the concept of urinary incontinence, leading to a wide range in estimated OAB prevalence, from 11.8 to 35.6% in various studies1,2,3. The EPIC study estimated the total annual cost of treating OAB in six Western countries to be around 9.7 billion euros4. The incidence of OAB is positively correlated with age, which will become a serious issue in aging societies, imposing a significant economic burden5. Besides financial concerns, OAB affects patients physically, socially, psychologically, and sexually. Therefore, addressing OAB-related issues and identifying modifiable and preventable factors are necessary.

Research5 indicates that overweight and obesity are significant risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms and can predict the exacerbation of OAB, with obese women being three times more likely to develop urgency urinary incontinence (UUI)6. Early studies7,8 have established a positive correlation between body weight indices and the prevalence of OAB. Obesity may contribute to OAB by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and affecting the neuromuscular function of the urinary tract, thus exerting adverse pressure on the bladder9. A recent study involving 200 participants10 found that individuals with OAB had higher BMI (30.1 kg/m2 vs. 27.1 kg/m2; P = 0.001) and larger waist circumference (97.8 cm vs. 89.0 cm; P = 0.001). However, traditional obesity assessment tools, such as BMI and waist circumference, have limitations in predicting the exacerbation of OAB because they do not effectively distinguish between fat and muscle mass.

The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) is a novel obesity metric introduced by Park et al.11, calculated by dividing waist circumference (cm) by the square root of body weight (kg). Unlike traditional weight measurement indices, WWI is easy to measure and standardizes waist circumference relative to weight. This method enhances the assessment of visceral fat accumulation, providing a more accurate measure than BMI and waist circumference (WC). Research indicates that higher WWI levels correlate with an increased incidence of urinary-related conditions, such as kidney stones and stress urinary incontinence12,13.

Studies have shown that dietary and inflammatory factors are associated with OAB. For example, a study from Turkey found a negative correlation between the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MeDAS) and OAB-V8 scores, suggesting that adherence to the Mediterranean diet could serve as a first-line treatment for patients with OAB symptoms. Furthermore, Zhang and colleagues demonstrated that higher DII scores, indicating a pro-inflammatory diet, were associated with an increased prevalence of urinary incontinence (UI) in American women under 65 years of age14. Additionally, other studies have shown a significant correlation between DII and obesity15,16. Therefore, we hypothesize that the relationship between WWI and OAB may be mediated by DII.

Currently, there are no studies in which DII mediates the relationship between WWI and OAB. Clinically, WWI could more accurately identify high-risk individuals for OAB, allowing for early intervention and treatment, thereby improving treatment outcomes, enhancing patients’ quality of life, and reducing socioeconomic burdens. Therefore, this study utilizes the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database to investigate the relationship between WWI and OAB and to explore the mediating role of DII between WWI and OAB. The aim is to provide new strategies and insights for the prevention and management of OAB.

Methods

Study population

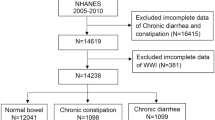

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted in the United States through household interviews and mobile examination centers. It evaluates the health and nutritional status of the American population. This study utilized data from seven NHANES cycles between 2005 and 2018, involving 70,190 participants. After excluding individuals younger than 20 years (n = 30,441), pregnant women (n = 708), those with missing or incomplete data on WWI or OAB (n = 6505), and those with missing or incomplete covariate data (n = 22,369), the final analysis included 10,167 participants. Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the selection process. NHANES is approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, with informed consent obtained from all participants. The data used in this study are de-identified and publicly available (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

Definition of WWI, DII, BRI, body fat percentage (BF%)

WWI is a novel obesity index that standardizes waist circumference by body weight, combining the strength of waist circumference while reducing its correlation with BMI. It is calculated by dividing waist circumference (cm) by the square root of body weight (kg) and then rounded to two decimal places. The formula is \(\text{WWI}=\text{Waist Circumference }(\text{cm})/\sqrt{\text{Body Weight }(\text{kg})}\). Additionally, definitions of all variables involved in this study are provided in Table S1. The definitions of DII, body fat percentage (BF%), and BRI are detailed in the supplementary material.

Diagnosis of OAB

According to the International Continence Society17, OAB is assessed by considering both urgent urinary incontinence (UUI) and nocturia. In the NHANES database, UUI and nocturia are evaluated through specific questionnaires. These detailed questionnaires are included in NHANES forms KIQ044, KIQ450, and KIQ480 (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005-2006/KIQ_U_D.htm). Following the collection of responses, the Overactive Bladder Syndrome Symptom Score (OABSS) is used to measure OAB severity17. Participants scoring 3 or above are diagnosed with OAB18,19. All relevant scores are listed in Table S2.

Covariables

Based on previous research20,21,22, the covariates included in the study are age, sex, race, marital status, education level, family poverty-income ratio (PIR), obesity, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. Detailed descriptions of these covariates are provided in Table S1.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.1). Sampling weights were utilized in all statistical analyses to ensure the estimated data’s national representativeness. In our study, “WTMEC2YR” was employed as the weighting variable, with the new weights (2005–2018) calculated as 1/7 × WTMEC2YR23. Data were weighted as specified, with continuous variables presented as mean ± standard deviation, and P-values computed using weighted linear regression models. For categorical variables, percentages (weighted N, %) and P-values were calculated using weighted chi-square tests. The association between WWI and OAB was examined using multivariate logistic regression models. WWI was categorized into quartiles and linear trend tests and P-values were computed to assess the consistency of the association. Three models were constructed: Model 1: no covariate adjustment; Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, education level, marital status, PIR, and race; Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, education level, marital status, PIR, race, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. Smooth curve fitting was used to further explore potential non-linear relationships between WWI and OAB. Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the association between WWI and OAB across different strata. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated for a one-unit increase in WWI. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education level, marital status, PIR, race, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, the discriminative ability of WWI, BRI, BMI, WC, and weight for predicting OAB was assessed using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and calculating the area under the curve (AUC). To verify the robustness of the results, analyses were also performed using unweighted data. Furthermore, the relationship between WWI and urgent urinary incontinence (UUI) was explored to enhance the reliability of the findings. The R software’s “mediation” package was used to calculate the mediation effect23.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

This study included 10,167 patients, with 15% having OAB and 85% without OAB. Among the participants, 48% were female and 52% were male, with a higher prevalence of OAB among females (58%). The prevalence of OAB was highest in individuals aged over 60 years (45%) compared to other age groups. Among different racial groups, non-Hispanic whites had the highest prevalence of OAB (66%). The prevalence of OAB was also higher in individuals with at least a high school education (80%). Physical activity was positively correlated with OAB prevalence, while the family poverty income ratio (PIR) was negatively correlated with OAB prevalence. Higher rates of obesity, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia were associated with increased OAB prevalence (P < 0.05). Among participants with OAB, WWI scores were higher (P < 0.05). Detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Additionally, to enhance the reliability of the study, unweighted baseline characteristics were provided in Table S3.

Relationship between WWI and OAB

Multivariate logistic regression models confirmed the association between WWI and OAB, as shown in Table 2. In Model 3, WWI was positively correlated with the risk of OAB (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.25–1.58). This positive correlation was more pronounced in higher quartiles of WWI, with odds ratios for Q2 (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.91–1.48), Q3 (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.24–2.04), and Q4 (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.41–2.37) showing a gradient compared to Q1. Trend tests using Q1 as the reference also confirmed this association (P < 0.05). Unweighted multivariate logistic regression models further validated the association between WWI and OAB, as detailed in Appendix Table S4. Additionally, smooth curve fitting was used to assess the relationship between WWI and OAB; Fig. 2 shows a linear positive correlation (non-linearity P = 0.903). To enhance the reliability of the study, the association between WWI and urgent urinary incontinence (UUI) was also evaluated (Tables S5 and S6, Figures S1 and S2).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses of the association between WWI and OAB are illustrated in Fig. 3, divided into (A) weighted and (B) unweighted analyses. We examined the stability of the relationship between WWI and OAB, as well as potential interactions, by adjusting for age, sex, education level, marital status, PIR, race, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses aimed to assess whether the association between WWI and OAB varied across different strata. In the subgroup analyses, no significant interactions between WWI and these stratifying variables were found in either the weighted or unweighted data (P > 0.05), indicating that the relationship is highly stable.

WWI as a predictor for OAB

We compared the predictive ability of WWI and various body measurement indicators for OAB likelihood by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) (Fig. 4). In this analysis, WWI demonstrated a strong advantage over the other five indicators (BRI, BMI, WC, Weight, BF%) with an AUC of 0.661 (95% CI 0.648–0.674), all P-values < 0.001.

Mediation analysis

The mediation analysis indicated that 5.02% of the relationship between WWI and OAB was mediated by DII (mediation proportion = indirect effect/(indirect effect + direct effect) * 100%, P = 0.016) (indirect effect = 1.30 × 10−5, P = 0.016; direct effect = 2.46 × 10−4, P < 0.001). Therefore, DII may play a mediating role in the association between WWI and OAB (Tables S7 and S8, Figure S3).

Discussion

Based on the NHANES database, this study used weighted multivariate logistic regression analysis to explore the relationship between WWI and the prevalence of OAB after adjusting for relevant covariates. The findings indicate a positive correlation between WWI and OAB prevalence: higher WWI values are associated with a higher incidence of OAB. Weighted multivariate adjusted restricted cubic spline (RCS) curves show a linear positive correlation between WWI and OAB. Additionally, WWI demonstrated superior predictive performance, as evidenced by the highest AUC. Finally, mediation analysis showed that DII mediated the association between WWI and OAB.

Obesity is an increasingly severe public health challenge, not only shortening the lifespan of healthy individuals but also increasing healthcare demands, causing significant productivity losses, reducing quality of life, and raising the likelihood of long-term medical issues. Recently, a study assessing obesity using BMI investigated the relationship between obesity and OAB symptoms, revealing that young women with a body fat percentage greater than 32% are more likely to suffer from OAB compared to those with a body fat percentage less than 32% (95%)24. A prospective cross-sectional study conducted in 2024, which included 1,351 patients, found that overweight or obese women were more likely to experience increased daytime urinary frequency and nocturia (P ≤ 0.01), with obesity significantly increasing the odds of severe OAB by 18.6 times, thereby severely impacting quality of life25. Another study involving 70 women showed that a 12-week weight loss program significantly alleviated OAB symptoms in overweight young women with OAB. This study used body composition analysis to assess skeletal muscle mass, body fat percentage, and other indicators. The results indicated that after 12 weeks of exercise, relevant weight indicators decreased, and OAB symptoms also showed some improvement26. Therefore, moderate exercise to reduce body weight and lower visceral fat to maintain it within a normal range may play a role in reducing the risk of OAB and could be beneficial for improving human health and quality of life.

Traditional diagnostic tools for identifying obesity, such as BMI, have certain limitations27. Recent research by Zhang and colleagues found that the Body Roundness Index (BRI) outperforms BMI, waist circumference, and weight in predicting OAB17. However, they did not compare WWI with BRI. In our study, we found that WWI is superior to BRI in predicting OAB. Additionally, we also included the body fat percentage (BF%) as a measurement. The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) is a recently proposed metric for evaluating central obesity. WWI has the advantage of being easy and convenient to measure in everyday life, standardizing waist circumference and mitigating the “obesity paradox” often seen with BMI. It is more suitable for use and promotion in developing regions, as it better reflects visceral fat accumulation and individual muscle content28. Recent studies have shown that visceral fat has a greater impact on metabolism and other diseases29. Kim et al. found that WWI is positively correlated with visceral fat and negatively correlated with muscle content, and it also avoids the limitations related to changes in visceral fat and muscle28.

When WWI was first introduced, research primarily focused on its diagnostic and prognostic value for liver and cardiovascular diseases30. Recent studies have indicated that WWI also has predictive capabilities for kidney function, compared to BMI and waist circumference (WC)31, potentially aiding in the development of better preventive and therapeutic strategies for patients. A 2024 cross-sectional study involving 2361 women aged 20 and older found a positive correlation between WWI and stress urinary incontinence. Furthermore, the association between WWI and stress urinary incontinence was found to be stronger than with traditional obesity indices13. Therefore, identifying accurate predictive methods for OAB is crucial. WWI is a newly discovered biomarker with limited research available, and there is a lack of direct evidence linking WWI to OAB. Our study finds that WWI is strongly associated with OAB.

Potential mechanisms linking obesity with the onset of overactive bladder (OAB) include: (1) Increased Intra-Abdominal Pressure: Research has shown that obesity, particularly central obesity, increases intra-abdominal pressure, which directly exerts pressure on the pelvic floor muscles32,33. Furthermore, Petros PE’s studies highlight the significant role of connective tissue in urinary incontinence34. Urodynamic studies by Richter et al. have demonstrated that intra-abdominal pressure rises not only with an increase in BMI but also with an increase in waist circumference8. (2) Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Adipose tissue, as an endocrine organ, secretes various adipokines, including leptin, adiponectin, TNF-α, and IL-6. Early studies have pointed out that obesity induces a systemic chronic low-grade inflammation state mediated by different inflammatory factors. In this state, adipose tissue secretes pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, and macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue can further contribute to conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases35. Concurrently, oxidative stress increases, evidenced by elevated lipid peroxidation products, protein carbonylation, reduced antioxidant systems, and decreased glutathione (GSH) levels36. Research suggests that inflammation and oxidative stress may induce bladder ischemia, which is associated with the development of OAB37. In summary, the pathogenesis of OAB may be linked to an imbalance in the formation and clearance of free radicals, triggering oxidative stress. (3) Metabolic Dysfunction: Obesity causes metabolic dysfunction, which may lead to atherosclerosis and insulin resistance. Atherosclerosis can affect various blood vessels, including coronary and pelvic arteries, leading to vascular endothelial dysfunction and pelvic ischemic changes, potentially causing detrusor and sphincter dysfunction. Studies have indicated a close relationship between pelvic ischemia and OAB38. Obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction involves the release of numerous pro-inflammatory factors from adipose tissue, which attack insulin receptors, resulting in insulin secretion defects and impaired insulin signaling pathways. This may progress to insulin resistance and, eventually, diabetes, with related neuropathy sharing a similar pathogenesis with OAB autonomic nervous system dysfunction39. Research indicates that increased nerve growth factor levels are associated with OAB40. Elevated nerve growth factor levels are observed in both OAB and obesity41, potentially causing dysfunction in bladder autonomic and peripheral sensory nerves, leading directly to urinary dysfunction, OAB development, and progression42.

The Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) reflects the inflammatory characteristics of dietary patterns, with higher DII values typically associated with elevated levels of inflammatory responses. These inflammatory responses may impact bladder function through various mechanisms. Firstly, chronic low-grade inflammation is considered a significant driving factor for many chronic diseases, including metabolic syndrome43 and cardiovascular diseases44, which are closely linked to the occurrence of OAB. Secondly, inflammation can lead to structural and functional alterations in smooth muscle, potentially resulting in bladder hyperactivity and the onset of OAB symptoms. Specifically, DII may induce inflammation in the lower urinary tract by affecting the secretion of pro-inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6)45. This inflammation can not only affect the neural innervation of the bladder but may also lead to hypersensitivity of bladder smooth muscle. Research has shown that inflammation of the bladder smooth muscle may increase sensitivity to neural signals46, thereby contributing to the symptoms of OAB. Additionally, WWI, as an indicator of abdominal fat distribution, is closely related to systemic metabolic status. An increase in abdominal fat correlates positively with higher DII values47, which in turn is linked to an elevated risk of OAB. Therefore, WWI may indirectly affect bladder function through systemic inflammation induced by DII by reflecting the degree of abdominal obesity. In summary, DII may play a crucial mediating role in the relationship between WWI and OAB, primarily through its induced systemic inflammation and its impact on bladder smooth muscle function. Further investigation into this mechanism will not only enhance our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying OAB but also provide new insights for future intervention strategies, emphasizing the importance of optimizing dietary patterns in reducing the risk of OAB.

This study has several advantages: (1) It innovatively investigates the relationship between the weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) and overactive bladder (OAB) in the U.S. population. (2) The current findings indicate a strong association between WWI and OAB. WWI, as a novel anthropometric measure, outperforms traditional methods in screening for OAB. (3) To enhance the reliability of this study, we not only described the unweighted baseline characteristics and developed an unweighted multivariable logistic regression model demonstrating a strong association between WWI and OAB, but we also assessed the relationship between WWI and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) using the same methods, thereby indirectly confirming the strong correlation between WWI and OAB.

However, this study has certain limitations: (1) The cross-sectional design of the study precludes establishing causality between the weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) and the prevalence of overactive bladder (OAB). (2) The NHANES database, which represents a cross-sectional survey of health and nutrition status in the U.S. population, may not be representative of populations worldwide. (3) Given that the NHANES data were collected through home interviews and mobile examination centers, there may be potential confounding factors and recall bias in the OAB data. (4) Due to the relatively low AUC value of WWI (0.661), it does not indicate that this metric is a strong predictor. Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. (5) Additionally, although we considered multiple covariates, such as age, sex, race, and other factors that may influence OAB, we cannot rule out the impact of all potential confounding variables, which may lead to bias in our results. Therefore, future research should employ longitudinal designs to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships among DII, WWI, and OAB. Additionally, alternative methods, such as Mendelian randomization, should be considered to validate our findings. (6) This study shows that the mediating effect of DII on the association between WWI and OAB is relatively weak, accounting for only 5.02%. In future research, we plan to explore a study framework that considers DII as the exposure variable, WWI as the mediator, and OAB as the outcome variable, to comprehensively investigate the complex relationships among DII, WWI, and OAB. (7) Lastly, as NHANES data primarily represent the U.S. population, the generalizability of our results to other populations remains uncertain. Future studies should incorporate more comprehensive biomarker assessments and investigate potential mechanisms through which WWI may influence OAB to provide a more comprehensive understanding of this relationship.

Conclusion

In summary, there is a significant association between elevated weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) and an increased likelihood of overactive bladder (OAB), indicating that WWI may serve as a useful tool for assessing OAB in clinical settings. In addition, DII mediates the above relationship, suggesting that an anti-inflammatory diet may help prevent OAB. Randomized controlled trials are needed to further explore the relationship between WWI and OAB symptoms. Additionally, effective management of obesity could positively impact the prevention of OAB. WWI has important clinical value in identifying OAB symptoms and facilitating early disease detection, offering new strategies for early diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract health issues. This approach could help alleviate the global economic burden associated with OAB. Future research is required to validate these findings and explore the underlying mechanisms further.

Data availability

The study involved the analysis of publicly available datasets. The data can be accessed at the following URL: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

References

Coyne, K. S. et al. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States stratified by sex and age. Urology 77, 1081–1087 (2011).

Irwin, D. E. et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: Results of the EPIC study. Eur. Urol. 50, 1306–1315 (2006).

Stewart, W. et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J. Urol. 20, 327–336 (2003).

Irwin, D. E. et al. The economic impact of overactive bladder syndrome in six Western countries. BJU Int. 103, 202–209 (2009).

Pomian, A., Lisik, W., Kosieradzki, M. & Barcz, E. Obesity and pelvic floor disorders: A review of the literature. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 22, 1880–1886 (2016).

Sheridan, W. et al. Weight loss with bariatric surgery or behaviour modification and the impact on female obesity-related urine incontinence: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Obes. 11, e12450 (2021).

Mommsen, S. & Foldspang, A. Body mass index and adult female urinary incontinence. World J. Urol. 12, 319–322 (1994).

Richter, H. E. et al. Urodynamic characterization of obese women with urinary incontinence undergoing a weight loss program. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 19, 1653–1658 (2008).

Fuselier, A., Hanberry, J., Margaret Lovin, J. & Gomelsky, A. Obesity and stress urinary incontinence: Impact on pathophysiology and treatment. Curr. Urol. Rep. 19, 10 (2018).

Baytaroglu, C. & Sevgili, E. Association of metabolic syndrome components and overactive bladder in women. Cureus 13, e14765 (2021).

Park, Y., Kim, N. H., Kwon, T. Y. & Kim, S. G. A novel adiposity index as an integrated predictor of cardiometabolic disease morbidity and mortality. Sci. Rep. 8, 16753 (2018).

Liu, H., Ma, Y. & Shi, L. Higher weight-adjusted waist index is associated with increased likelihood of kidney stones. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1234440 (2023).

Sun, D., He, H., Luo, B. & Xie, B. The association between weight-adjusted-waist index and stress urinary incontinence in female adults: A population-based study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 56, 1851–1858 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Associations between the dietary inflammatory index and urinary incontinence among women younger than 65 years. Sci. Rep. 11, 9340 (2021).

Zhang, L., Peng, H., Wang, Y. & Ba, H. Association of dietary inflammatory index with obesity among children and adolescents in the United States NHANES cohort: A population-based study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 50(1), 14 (2024).

Gholamalizadeh, M. et al. Associations between the dietary inflammatory index with obesity and body fat in male adolescents. BMC Endocr. Disord. 22, 115 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between body roundness index and overactive bladder: Results from the NHANES 2005–2018. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 184 (2024).

Zhang, D., Yan, Z., He, J., Yao, Y. & Liu, K. The exposure to volatile organic compounds associate positively with overactive bladder risk in U.S. adults: A cross-sectional study of 2007–2020 NHANES. Front. Public Health 12, 1374959 (2024).

Cheng, Y. et al. Prevalence and trends in overactive bladder among men in the United States, 2005–2020. Sci. Rep. 14, 16284 (2024).

Kim, S. Y., Bang, W. & Choi, H. G. Analysis of the prevalence and associated factors of overactive bladder in adult Korean men. PLoS ONE 12, e0175641 (2017).

Lin, W. et al. Association of socioeconomic status and overactive bladder in US adults: A cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative data. Front. Public Health. 12, 1345866 (2024).

Mckellar, K., Bellin, E., Schoenbaum, E. & Abraham, N. Prevalence, risk factors, and treatment for overactive bladder in a racially diverse population. Urology 126, 70–75 (2019).

Wu, R. & Gong, H. The association between non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The mediating role of dietary inflammatory index. Front. Nutr. 11, 1427586 (2024).

Hagovska, M. et al. The relationship between overweight and overactive bladder symptoms. Obes. Facts 13, 297–306 (2020).

Alsannan, B. et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder among overweight and obese women: A prospective cross-sectional cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 295, 59–64 (2024).

Hagovska, M. et al. Effect of an exercise programme for reducing abdominal fat on overactive bladder symptoms in young overweight women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 31, 895–902 (2020).

Myint, P. K., Kwok, C. S., Luben, R. N., Wareham, N. J. & Khaw, K.-T. Body fat percentage, body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of mortality and cardiovascular disease. Heart Br Card Soc. 100, 1613–1619 (2014).

Kim, N. H., Park, Y., Kim, N. H. & Kim, S. G. Weight-adjusted waist index reflects fat and muscle mass in the opposite direction in older adults. Age Ageing 50, 780–786 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Association between weight-adjusted waist index and depressive symptoms: A nationally representative cross-sectional study from NHANES 2005 to 2018. J. Affect. Disord. 350, 49–57 (2024).

Shen, Y., Wu, Y., Fu, M., Zhu, K. & Wang, J. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index with hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis: A nationally representative cross-sectional study from NHANES 2017 to 2020. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1159055 (2023).

Qin, Z. et al. The association between weight-adjusted-waist index and increased urinary albumin excretion in adults: A population-based study. Front. Nutr. 9, 941926 (2022).

Whitcomb, E. L., Lukacz, E. S., Lawrence, J. M., Nager, C. W. & Luber, K. M. Prevalence and degree of bother from pelvic floor disorders in obese women. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 20, 289–294 (2009).

Hunskaar, S. A systematic review of overweight and obesity as risk factors and targets for clinical intervention for urinary incontinence in women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 27, 749–757 (2008).

Petros, P. E. P. & Woodman, P. J. The integral theory of continence. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 19, 35–40 (2008).

Zeng, Q., Li, N., Pan, X.-F., Chen, L. & Pan, A. Clinical management and treatment of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9, 393–405 (2021).

Rani, V., Deep, G., Singh, R. K., Palle, K. & Yadav, U. C. S. Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci. 148, 183–193 (2016).

Wu, Y.-H. et al. Bladder hyperactivity induced by oxidative stress and bladder ischemia: A review of treatment strategies with antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6014 (2021).

Otunctemur, A. et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on stress urinary incontinence in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 46, 1501–1505 (2014).

Kang, Y. E. et al. The roles of adipokines, proinflammatory cytokines, and adipose tissue macrophages in obesity-associated insulin resistance in modest obesity and early metabolic dysfunction. PLoS ONE 11, e0154003 (2016).

Bulló, M., Peeraully, M. R., Trayhurn, P., Folch, J. & Salas-Salvadó, J. Circulating nerve growth factor levels in relation to obesity and the metabolic syndrome in women. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 157, 303–310 (2007).

Meng, E., Lin, W.-Y., Lee, W.-C. & Chuang, Y.-C. Pathophysiology of overactive bladder. Low Urin. Tract Symptoms 4(Suppl 1), 48–55 (2012).

Hsu, L.-N., Hu, J.-C., Chen, P.-Y., Lee, W.-C. & Chuang, Y.-C. Metabolic syndrome and overactive bladder syndrome may share common pathophysiologies. Biomedicines 10, 1957 (2022).

Esposito, K. & Giugliano, D. The metabolic syndrome and inflammation: Association or causation?. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. NMCD 14, 228–232 (2004).

Tylutka, A. et al. Assessment of metabolic syndrome predictors in relation to inflammation and visceral fat tissue in older adults. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 89 (2023).

Azarbayjani, K., Jahanian Sadatmahalleh, S., Mottaghi, A. & Nasiri, M. Association of dietary inflammatory index with C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in women with and without polycystic ovarian syndrome. Sci. Rep. 14, 3972 (2024).

Birder, L. A. Urinary bladder, cystitis and nerve/urothelial interactions. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 182, 89–94 (2014).

Tavakoli, A. et al. Dietary inflammatory index (DII) may be associated with hypertriglyceridemia waist circumference phenotype in overweight and obese Iranian women: A cross sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 14, 312 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the NHANES database for all the data provided.

Funding

This study was not financially supported by any governmental, corporate, or non-profit entities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. contributed to the original draft, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, and Formal analysis. Q.H. contributed to the original draft, Methodology, and Formal analysis. J.M. contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, and Data curation. S.C. contributed to Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, and Data curation. H.G. was involved in Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The data survey conducted by NHANES has been approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB). All information from the NHANES program is available and free for the public, so an individual investigator was not necessary to obtain approval from the institution’s internal ethics review board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, S., He, Q., Zhao, J. et al. Association of weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) with overactive bladder (OAB): a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2005–2018. Sci Rep 15, 13207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98050-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98050-8