Abstract

This article fully investigates the hydrogen fuel jet mixing behind the strut with a serpentine injector at a supersonic combustion chamber. The main goal of this work is to analyze the three-dimensional flow of hydrogen jet released from the serpentine nozzle by computational technique. The role of serpentine nozzle height is also examined to find the optimum location for fuel mixing. Meanwhile, the extruded serpentine nozzle located behind the strut is also studied. The strength of circulation in these configurations is compared and our results show that the fuel circulation strength is improved when the serpentine nozzle is located in a higher height behind the strut. Moreover, a comparison of the fuel mixing behind the strut indicates this injector has significantly higher fuel mixing efficiency (about 40%) in comparison with a circular nozzle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scramjet engine, a cornerstone of hypersonic propulsion technology, operates by compressing incoming air at supersonic speeds and combusting it with fuel to generate thrust. Achieving efficient fuel-air mixing in the combustion chamber is a critical challenge due to the extremely short residence time and high-speed airflow. The success of the scramjet largely depends on innovative injector designs that ensure rapid and effective mixing of the fuel with the airstream under extreme operating conditions1,2,3.

Among various injection strategies, serpentine injectors have garnered attention for their ability to enhance fuel-air mixing through a combination of passive mechanisms. By introducing secondary flow structures, such as vortices and shear layers, the serpentine injector promotes turbulent mixing, which is crucial in overcoming the inherent challenges of high-speed combustion. Additionally, its design can potentially reduce total pressure loss, which is a critical factor for maintaining overall engine efficiency4,5,6.

A particularly intriguing aspect of the serpentine injector is its ability to generate large-scale vortices in the wake of the injector, especially when positioned behind a strut. These vortices play a pivotal role in the mixing process within the combustion chamber. The interaction between the vortices shed by the serpentine injector and the high-speed shear layers of the supersonic flow intensifies turbulent mixing7,8,9. Specifically, counter-rotating vortices enhance cross-sectional mixing of fuel and air, while longitudinal vortices stretch and fold the mixing layers, increasing the contact area between the two fluids10,11.

When placed downstream of a strut, the serpentine injector’s vortices synergize with the wake turbulence generated by the strut itself12,13. The strut, commonly used to anchor injectors or other flow control elements, introduces regions of low pressure and recirculation zones. The vortices produced by the serpentine injector interact with these recirculation zones, creating a complex flow pattern that further enhances fuel entrainment into the air stream14,15. This interaction ensures that the fuel remains well-dispersed and mixed throughout the combustion chamber, even under the high-strain and short-duration environment of a scramjet16,17.

This study focuses on the computational investigation of serpentine injectors for fuel mixing within the combustion chamber of a scramjet engine, with a particular emphasis on the role of vortex structures generated by the injector and their interaction with strut-induced flow features18,19,20. Using advanced numerical simulations, we evaluate the injector’s performance in terms of mixing efficiency, flow uniformity, and pressure loss under realistic operating conditions. The results provide critical insights into the flow dynamics and highlight the potential of serpentine injectors as a promising solution for the fuel injection challenges in scramjet engines21,22,23. By optimizing the design and understanding the physics of vortex generation and interaction, this research aims to contribute to the advancement of hypersonic propulsion technology.

The efficient injection of the hydrogen gas behind the strut via a serpentine injector is investigated in this research article. The fuel jet characteristic released from the serpentine injector has been studied to reveal the importance of the injector shape on the fuel penetration inside the combustor with a strut. The computational technique is used for the modeling of the hydrogen gas released from three different serpentine injectors at supersonic flow. The effects of the extruded nozzle as well as nozzle location on the fuel jet mixing are fully explained in this paper. A three-dimensional model of the serpentine injection system is used since the flow of the hydrogen jet should be analyzed by real physics of the flow. Circulation analysis is also conducted for the evolution of this innovative model.

Computational methodology and main governing equations

The flow inside the combustor of the scramjet with an injection of the fuel behind the strut is fully compressible and turbulent24,25,26. The main focus of this work is to visualize the real fuel mixing and distribution downstream of the strut without reactions27,28. Thus, RANS equations are considered for the modeling of the supersonic flow within the combustor with the SST turbulence model29,30, and31. As hydrogen is the fuel for the injection from the serpentine injector, the species transport equation is also required for the modeling of the secondary gas in our domain32,33. The ideal gas assumption is done for the modeling of the gas behavior and the energy equation is also coupled due to shock wave production inside the model at the supersonic combustor. The main governing equations are fully available in previous studies34,35, and36.

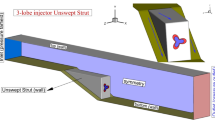

The proposed serpentine injector configurations are demonstrated in Fig. 1. The initial radius (rl) and final radius (r2) of the designed serpentine are 0.5 mm, and 2.25 mm, respectively. The present work also investigated the vertical location of the serpentine injector at two heights of L1 = 5 mm and L2 = 2.7 mm. The width and height of the strut are 5 mm and 10 mm, respectively. The extruded serpentine model is also simulated in this work and the model with extruded length of 10 mm behind the strut is also simulated in this work. The length of the extruded injector is chosen arbitrary and this length is chosen to investigate the use of this technique for the injection of the fuel behind the strut. The supersonic air flow with Mach = 2 and atmospheric pressure enters from the inlet and the hydrogen is also injected from the serpentine nozzle with Mach = 1 with 30% total pressure of free air stream. The length of the domain upstream and downstream of the strut is 20 mm and 70 mm, respectively. The applied condition at the inlet is pressure far-field and the outlet is pressure outlet (Fig. 2). The bottom is assumed symmetry and two sides of the model are assumed symmetry. The schematic structure of the fuel jet released from the nozzle is also depicted in the figure.

In Fig. 3, the generated cells for one of the proposed serpentine models are illustrated. The grid size is adjusted based on the importance of the domain to optimize the grid cells and run time. In fact, critical regions near serpentine injectors have higher grid resolution while large grids are generated at a far distance near the outlet. The grid study is also conducted and the fuel concentration on the specific plane positioned 15 mm behind the strut is evaluated to ensure that the produced grid is not effective on the obtained results. Figure 4 presents the archived results from different produced grids. The third grid is selected as a final grid for this investigation. A structured grid is produced to achieve high-precision results and the Y + value of the grids in the final grids is less than 4.

Results and discussion

The important step for the computational modeling of the fuel jet mixing in the combustor is to compare the numerical data with existing experimental data (Table 1). The present work has modeled the single circular nozzle model behind the strut since the experimental results37 of the model are available in the context. The velocity changes behind the strut on the plane positioned 125 mm behind the strut are compared with the experimental data and a comparison of the results shows that the selected technique for the modeling of the fuel mixing is reliable for the proposed serpentine injector.

The 3-dimensional features of the hydrogen jet released from the serpentine nozzle in the introduced configurations are displayed in Fig. 5. In case 1, the fuel jet released from the center of the strut vertical plane expands in all directions while its non-uniformity of the jet is preserved. The main attitude of proposing serpentine injectors is the layer shape of the jet since this shape of the nozzle would produce the layer jet flow which has great mixing efficiency due to the production of the vertical flow within these layers. When the serpentine injector moves up behind the strut (case 2), the fuel jet near the outlet is highly under the impact of the supersonic free stream flow from an upward direction and consequently, the jet expansion occurs after a limited distance as shown in the figure. In fact, the produced vortices in the gap of the serpentine nozzle and the bottom are enable to distribute the hydrogen flow with more power. In the extruded serpentine model (case 3), the power of the induced vortices behind the strut is not high near the serpentine injector and consequently, the expansion of the fuel jet in this model is not efficient. However, the fuel jet diffusion in the streamwise direction is more efficient since the free stream airflow in the vicinity of the outlet is higher.

The Mach contour on the mid-plane is also compared to investigate how the contact of the free stream with the fuel jet layer in the suggested configurations differs from the fuel mixing performance in these configurations (Fig. 6). In case 1, the gap of the free stream shear layer, initiated from the top edge of the strut, and the fuel jet is a high potential for the formation of the circulation due to the subsonic region. As the position of the serpentine jet moves up (Case 2), the induced vortices vanish in the top of the jet and consequently, the gap between the bottom and the jet is the only potential region for the formation of the circulation. Unlike previous configurations, the shear layer contact jet flow was released from the extruded serpentine nozzle in case 3. Thus, high shock contact is noticed in this model.

The mixing zone downstream of the three suggested serpentine injectors has been examined to unveil the role of the produced vortices on the fuel distribution of these models. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the power strength of the bottom vortices pushes the fuel jet to the upward direction although the up vortices improve the fuel mixing top of the jet. In case 2, the mass fraction of the hydrogen is less diffused into the free stream and the core of the hydrogen jet is deflected by the main air stream although there is a large circulation in the bottom of the hydrogen jet in this model. In the extruded serpentine nozzle, the jet concentration is highly lower than in other configurations since the shear layer disturbs the hydrogen jet after the nozzle. As mentioned before, the higher interaction of the free stream with hydrogen along with the layer formation of the fuel jet increases the fuel jet mixing in this model.

The contour of the mixing zone downstream of the serpentine nozzle is demonstrated in Fig. 8. The figure of the fuel mixing in these locations displays the trend of the fuel jet changes in these models. The change in the fuel concentration confirms that the jet behind the serpentine nozzle has a non-uniform distribution and this effect would improve the fuel distribution behind the strut. The spiral shape of the nozzle deforms the core of the jet and consequently, the boundary of the hydrogen jet permits the air stream to diffuse into the jet. In case 2, the jet would preserve the main core since the spiral feature of the jet is limited by the free stream. As expected, a downward extension of the mixing zone in this model is higher while the core of the jet remains at the top. In the extruded serpentine model, the fuel mixing is not extended due to the contact of the free stream shear layer at the jet outlet.

The 3-D flow around the serpentine injector with Mach contour on the mid-plane of these models is illustrated in Fig. 9. The figure exhibits the jet and free stream in these cases along with Mach contour to evaluate the flow difference in these introduced models. The flow stream in these models indicates that the gap between the fuel jet and the bottom is the source of the vortices which greatly change the fuel distribution behind the nozzles. Meanwhile, the serpentine shape of the injector results in the local velocity gradient and consequently, the core of the jet would be the source of the vortex. As shown in the figure, in the extruded serpentine model, the core of the produced vortex behind the strut did not contact with the jet outlet. Thus, the induced vortices could not improve the penetration of the fuel jet.

The contour of Mach and stream behind the strut with the serpentine nozzle in two different heights are illustrated in Fig. 10. The vortex pair induced by the serpentine injector is noticed by the reason for the velocity change. The Mach contour demonstrates how the velocity change expands the circulation downstream of the serpentine nozzle. A comparison of these two cases shows that the change of the injector height has a direct impact on the size of the vortex size while this role is limited near the injector.

The circulation strength behind the strut for case 1 and case 2 is evaluated and the obtained results are plotted in Fig. 11. The archived data related to the circulation strength downstream of these two models indicates that the circulation strength is improved when the serpentine nozzle is located in higher heights behind the strut. Indeed, the circulation expanded more when the jet was positioned near the top of the strut. The circulation strength also discloses that this trend remains downstream. The formulation for calculation of the circulation is as follows:

The comparison of the fuel mixing behind the strut for circular and serpentine nozzle is also done and Fig. 12 presents the reached data. The mixing efficiency results of case 1 and 2 are almost identical and consequently, they are presented as one plot in this figure. As plotted in the figure, the mixing efficiency near the jet outlet of circular and serpentine nozzle is practically identical. However, when the jet moves downstream (more than 10 mm), the fuel mixing of the serpentine nozzle is higher than the circular one about 40%. The higher performance of the serpentine nozzle is related to the superior circulation power induced by the spiral shape of the nozzle. The calculation of fuel mixing is done by following equations:

where.

where \(Y_{{H_{2} }}^{{st}}\) is the stoichiometric hydrogen concentration for a fuel/air mixture

Figure 13 illustrates the variation of the total pressure loss downstream of the two cases of serpentine injector as well as simple circular injector38. The total pressure loss across the combustor is largely unaffected by changes in the separation distance. The results of pressure loss indicate that the use of serpentine injector decreases the pressure loss behind the strut. The slight variation observed in total pressure loss could be attributed to weaker trailing edge shock waves.

Conclusion

This study fully investigated the technique of the serpentine injector behind the strut of a supersonic combustion chamber. The compressible hydrogen jet flow released from the serpentine nozzle is simulated via the CFD method to visualize the flow of the hydrogen jet diffusion mechanism. The flow stream and mixing zone behind the serpentine nozzle in three configurations are compared to disclose the important feature that improves the fuel penetration downstream of this type of injector. To examine the performance of the serpentine injector, different heights, and extruded serpentine nozzle are simulated. The comparison of the nozzle height indicates that fuel circulation power improves when the jet nozzle moves to a higher height since the down circulation expands. Meanwhile, a comparison of the mixing performance of the circular and serpentine nozzle confirms the superiority of the serpentine nozzle downstream of the strut located in the combustor of the scramjet engine. The circulation strength in these configurations is analyzed, and our findings reveal that positioning the serpentine nozzle at a greater height behind the strut enhances fuel circulation. Additionally, when evaluating fuel mixing downstream of the strut, this injector demonstrates a notably higher mixing efficiency—approximately 40%—compared to a conventional circular nozzle.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ali, N. B. et al. The usage of non-aligned multi-circular winding injectors for efficient fuel mixing inside the scramjet engine. Energy. 298, 131403 (2024).

Barzegar, G. M. Aerodynamic Heating in Supersonic and Hypersonic Flows: Advanced Techniques for Drag and Aero-Heating Reduction, 1st ed. (Elsevier, 2022).

Barzegar Gerdroodbary, M. Scramjets: Fuel Mixing and Injection Systems, 1–220 (Elsevier Ltd., 2020).

Ma, N., Meng, J., Luo, J. & Liu, Q. Optimization of thermal-fluid-structure coupling for variable-span inflatable wings considering case correlation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 153, 109448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2024.109448 (2024).

Sun, Q., Chen, J., Zhou, L., Ding, S. & Han, S. A study on ice resistance prediction based on deep learning data generation method. Ocean Eng. 301, 117467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117467 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Impacts of fuel stage ratio on the morphological and nanostructural characteristics of soot emissions from a twin annular premixing swirler combustor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58 (24), 10558–10566. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c03478 (2024).

Hassanvand, A., Gerdroodbary, M. B. & Abazari, A. M. Injection of hydrogen Sonic multi-jet on inclined surface at supersonic flow. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C IJMPC. 32 (03), 1–14 (2021).

Zeng, W., Zhou, P., Wu, Y., Wu, D. & Xu, M. Multi-cavitation states diagnosis of the vortex pump using a combined DT-CWT-VMD and BO-LW-KNN based on motor current signals. IEEE Sens. J. 24 (19), 30690–30705. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3446170 (2024).

Sun, X. et al. Heat transfer augmentation, endothermic pyrolysis and surface coking of hydrocarbon fuel in manifold microchannels at a supercritical pressure. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 161, 108564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.108564 (2025).

Guo, S., Lan, Y. & Li, G. Design and optimization of a 500 kw multi-cylinder double-acting free piston Stirling engine for deep-sea nuclear power system. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 180, 105588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2024.105588 (2025).

Fallah, K., Gerdroodbary, M. B., Ghaderi, A. & Alinejad, J. The influence of micro air jets on mixing augmentation of fuel in cavity flameholder at supersonic flow. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 76, 187–193 (2018).

Jiang, Y., Hajivand, M., Sadeghi, H., Barzegar Gerdroodbary, M. & Li, Z. Influence of trapezoidal lobe strut on fuel mixing and combustion in supersonic combustion chamber. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 106841 (2021).

Omar, I. et al. Usage of double injector for efficient mixing of the fuel behind the ramp injector at supersonic combustion chamber. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1151 (2025).

Zhou, H., et al. Design of a fuel Explosion-Based Chameleon-Like soft robot aided by the comprehensive dynamic model. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 40010. https://doi.org/10.34133/cbsystems.0010 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Probing the combustion characteristics of micron-sized aluminum particles enhanced with graphene fluoride. Combust. Flame. 272, 113858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2024.113858 (2025).

Zhou, H. Y., Wang, X. G., Li, X. & Cui, N. G. Synergistic planning for hypersonic vehicles with an analytic hybrid algorithm. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 61 (1), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2024.3442162 (2025).

Xu, Z. et al. Assessing the particulate matter emission reduction characteristics of small turbofan engine fueled with 100% HEFA sustainable aviation fuel. Sci. Total Environ. 945, 174128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174128 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. Cyclic coupling and working characteristics analysis of a novel combined cycle engine concept for aviation applications. Energy 301, 131747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.131747 (2024).

Gerdroodbary, M. B., Jahanian, O. & Mokhtari, M. Influence of the angle of incident shock wave on mixing of transverse hydrogen micro-jets in supersonic crossflow. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 40 (30), 9590–9601 (2015).

Billig, F. S., Waltrup, P. J. & Stockbridge, R. D. Integral-Rocket dual combustion ramjets: A new propulsion concept. J. Spacecr. 17 (5), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.2514/3.57760 (1980).

Pish, F., Hassanvand, A., Gerdroodbary, M. B. & Noori, S. Viscous equilibrium analysis of heat transfer on blunted cone at hypersonic flow. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 14, 100464 (2019).

Zhou, L. et al. Numerical study of the cavitation performance of an Ice-Blocked propeller considering the free surface effect. Water 16 (22), 3260. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16223260 (2024).

Zhou, L., Zheng, S., Ding, S., Xie, C. & Liu, R. Influence of propeller on brash ice loads and pressure fluctuation for a reversing Polar ship. Ocean Eng. 280, 114624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.114624 (2023).

Sheidani, A., Salavatidezfouli, S., Stabile, G., Gerdroodbary, M. B. & Rozza, G. Assessment of icing effects on the wake shed behind a vertical axis wind turbine. Phys. Fluids. 35, 9 (2023).

Barzegar Gerdroodbary, M., Shiryanpoor, I., Salavatidezfouli, S., Abazari, A. M. & Pascoa, J. C. Optimizing aerodynamic stability in compressible flow around a vibrating cylinder with deep reinforcement learning. Phys. Fluids. 36, 12 (2024).

Shang, S., et al. The impact of inner air jet on fuel mixing mechanism and mass diffusion of single annular extruded nozzle at supersonic combustion chamber. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 146, 106869 (2023).

Li, Y., et al. Comparison of the different shapes of extruded annular nozzle on the fuel mixing of the hydrogen jet at supersonic combustion chamber. Energy. 128142 (2023).

Ma, L., et al. The influence of the struts on mass diffusion system of lateral hydrogen micro jet in combustor of scramjet engine: Numerical study. Energy 128119 (2023).

Shi, X., et al. Influence of coaxial fuel–air jets on mixing performance of extruded nozzle at supersonic combustion chamber: numerical study. Phys. Fluids. 35, 5 (2023).

Shi, Y., et al. Influence of lateral single jets for thermal protection of reentry nose cone with multi-row disk spike at hypersonic flow: computational study. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 6549 (2023).

Iranmanesh, R., Alizadeh, A. & Faraji, M. Numerical investigation of compressible flow around nose cone with multi-row disk and multi coolant jets. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 787 (2023).

Abdollahi, S. A., Rajabikhorasani, G. & Alizadeh, A. Influence of extruded injector nozzle on fuel mixing and mass diffusion of multi fuel jets in the supersonic cross flow: computational study. Sci. Rep. 13, 12095. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39306-z (2023).

Alizadeh, A. et al. Using shock generator for the fuel mixing of the extruded single 4-lobe nozzle at supersonic combustion chamber. Sci. Rep. 14, 6405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57103-0 (2024).

Gerdroodbary, M., Fallah, K. & Pourmirzaagha, H. Characteristics of transverse hydrogen jet in presence of multi air jets within scramjet combustor. Acta Astronaut. 132, 25–32 (2017).

Seraj, H., Hosseinnejad, F., Rostamiyan, Y. & Fallah, K. Improvement of fuel mixing of single ejected 2-lobe fuel injector using shock generator at supersonic flow. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 50, 939–950 (2024).

Ali, N. B. et al. El-Shafay. Computational study of the coaxial air and fuel jet through a 3-lobe strut injector for efficient fuel mixing in a supersonic combustion chamber. Energy. 311, 133276 (2024).

Waidmann, W. et al. Supersonic combustion of hydrogen/air in a scramjet combustion chamber. Space Technol. 6, 421–429 (1994).

Kummitha, O. R. & Pandey, K. M. Effect of wavy wall strut fuel injector on shock wave development and mixing enhancement of fuel and air for a scramjet combustor. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 8 (1), 362e75 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R41), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-2928-03”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. and R.H.R. wrote the main manuscript text and P.K.S. and S.D. and T.G. prepared figures and K.G. and L.K. and A.S.E. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mir, A., Rasheed, R.H., Singh, P.K. et al. Usage of serpentine injector for hydrogen mixing at combustion chamber of scramjet engine via a computational study. Sci Rep 15, 13089 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98077-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98077-x