Abstract

The static pressure pile installation technique is extensively utilized in the construction of bridge pile foundations. However, the presence of pebble interlayers within the strata is a common occurrence. To examine the impact of such pebble interlayers on the installation of pipe piles using static pressure, model tests were executed to scrutinize parameters including pile penetration force, ultimate bearing capacity, lateral soil pressure, and the distribution of pile penetration resistance under two distinct working conditions: standard sand and pebble interlayer during pile penetration. The objective was to elucidate the effect of pebble interlayers on pile penetration. The findings indicated that a pebble layer with a thickness equivalent to 2.5 times the diameter of the pile could result in a 1.3-fold increase in the average pile penetration force, and at its peak, could elevate the pile penetration force by as much as 1.8-fold. Furthermore, the lateral soil pressure surrounding the pile exhibits a nonlinear escalation. In scenarios where the foundation soil is uniform, the lateral soil pressure at a specific point around the pile will markedly increase due to the soil compression effect generated as the pile head approaches that location. Nonetheless, after the pile head surpasses this point, the lateral soil pressure will experience a rapid decline due to the unloading effect precipitated by the failure of the soil surrounding the pile. When the pile head traverses through the pebble interlayer, it induces an augmentation in the lateral soil pressure within the underlying soil stratum. Additionally, drawing upon Meyerhof’s theory of ultimate bearing capacity, a revised calculation formula for pile penetration resistance in both uniform and pebble-interbedded sandy soil foundations has been formulated. This formula can be employed to estimate the pile penetration resistance of static pressure piles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern bridge construction, the pile foundation is a crucial component of the overall bridge structure, and its construction quality directly affects the long-term safety and stability of the bridge. In recent years, as bridge engineering has expanded into increasingly complex geological areas, the challenges associated with pile foundation construction have grown significantly. These challenges may result in issues such as uneven settlement, difficulty in pile penetration, and structural deformation1,2,3. In particular, geological conditions involving pebble interlayers have been found to significantly influence the penetration process of static pressure piles. The presence of pebble layers not only increases penetration resistance but also leads to uneven stress distribution along the pile shaft, ultimately affecting the bearing capacity and stability of the foundation.

Currently, many researchers have studied the distribution characteristics and driving mechanisms of pile resistance, tip resistance, and shaft friction during static pressure pile installation. Jiang et al.4 investigated the differences in pile driving resistance, tip resistance, and shaft friction for model piles with different head shapes in sandy soil. Liu et al.5 used fiber Bragg grating sensors to measure stress characteristics and residual stress distribution during pile penetration in cohesive soil foundations. Additionally, the distribution of lateral compressive stress and its relation to ultimate bearing capacity have also received attention. The variation in lateral stress along the embedded depth after pile installation is primarily influenced by the soil squeezing effect. Previous studies have explored the variation in soil pressure around piles under such effects6,7. Zhu et al.8 through large scale model test and advanced monitoring technology, the soil plug effect, pile-soil interface stress distribution and time effect of open pipe pile in sand were revealed. However, these studies have mostly been conducted in single-layer soil conditions such as sandy or cohesive soils, and relatively few have focused on multi-layer foundations with embedded pebble layers.

To enrich the understanding of pebble-interlayer foundations, several recent studies have emerged. Li et al.9 compared more than 600 piles with grouting and without grouting, and the statistical results showed that post-grouting technology was most widely used in gravel and pebble strata. Through experimental investigations, Du et al.10,11,12 revealed that post-grouting treatment leads to a substantial improvement in the load-bearing performance and strengthening efficiency of pile foundations embedded in pebble-bearing strata. Wang et al.13 based on the model test and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, the improvement effect of post-grouting technology on bearing capacity of bored pile in pebble stratum is evaluated. It is found that the slurry can effectively fill the pebble layer at the pile end and improve the bearing capacity. Li et al.14 established a three-dimensional diffusion model of grout in gravel pebble layer based on COMSOL Multiphysics, and revealed the law of influence of parameters such as grouting pressure and diffusion coefficient on grout diffusion. Lin et al.15 developed a new type of lead hole backfill composed of silty clay, bentonite, sawdust and cement, which solved the difficult problem of the construction of geological steel sheet pile in river pebble layer. Kang et al.16 revealed the stress distribution and vertical bearing capacity of PHC pipe piles in pebble layers using field-monitored static load tests. Liu17,18 explored the relationship between the final construction pressure and ultimate bearing capacity of prefabricated piles installed in pebble foundations. Huang et al.19 analyzed the standard values of shaft friction and estimated the pull-out bearing capacity of piles in pebble soil. Jiang et al.20 studied the load transfer behavior of expanded-base piers in pebble interlayers through static load tests. Yang et al.21 conducted a reliability analysis of hand-excavated piles in pebble layers using limit state equations and random variable calibration methods, identifying key influences on the reliability index.

In summary, previous research has provided important insights into the mechanical behavior, load transfer mechanisms, and reliability of pile foundations in pebble interlayer conditions. However, most existing studies primarily focus on macroscopic performance indicators such as ultimate bearing capacity, with limited investigation into the dynamic evolution of soil pressure on the pile side and internal stress distribution during the pile penetration process. Moreover, the interaction between the pile and complex stratified soils—especially the impact of high-resistance pebble interlayers on penetration behavior—remains insufficiently explored.

This study aims to fill this gap by systematically investigating the stress characteristics of static pressure piles and the variation of lateral soil pressure during installation in foundations with pebble interlayers. Based on experiments and analysis, the study offers new insights into the pile–soil interaction mechanism under such complex geological conditions, which have not been adequately addressed in the existing literature. The findings provide both theoretical support and practical guidance for optimizing pile design and construction in similar strata.

Overview of model experiments

Static pressure pile installation device

The static pressure pile installation device uses a YAW-2000 long axis pressure testing machine. The maximum test force of this device reaches 2000 kN, and its adjustable height range is 1500–3000 mm. Users can set the test force and actuator loading speed in the device, and then the actuator will be loaded to the force value at the preset displacement speed and maintain the test force for testing. The model box size of the device is 1000 mm (length) × 800 mm (width) × 1200 mm (height), welded from high carbon steel angle iron, surrounded by transparent acrylic sheets with a thickness of 10 mm. In order to eliminate the lateral boundary effect22, the minimum margin between the model pile and the model box is 380 mm, approximately 9D (D is the pile diameter), as shown in (Fig. 1).

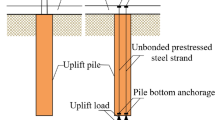

Model pile production

The model testing pile is made of galvanized steel material, with a length of 800 mm, a diameter of 42 mm, and a wall thickness of 3 mm. The similarity ratio is 1:15, as shown in (Fig. 2). To avoid inaccurate test results due to strain gauge detachment, sand contact friction, and compression deformation during pile penetration, the strain gauge model BFH120-5AA should be pasted onto the inner wall of the model pile. The resistance of the strain gauge is 120 Ω, and the sensitivity coefficient is 2.0 ± 1%. The strain data is automatically collected through the DH3816N static stress-strain testing and analysis system. The range of the earth pressure gauge is 0-300 kPa, which can meet the requirements of this experiment. Prior to testing, the strain gauge system underwent a comprehensive calibration process to ensure data accuracy. The procedure included initial inspections (appearance and resistance testing), zero-point calibration under no-strain conditions, and sensitivity calibration using known loading conditions. The overall measurement error was within ± 2% of the full scale. In addition, the DH3816N static stress-strain system was zero-adjusted before each test, and the consistency of strain readings was verified through repeated trials to ensure the reliability of the data.

In this experiment, all soil pressure gauges were arranged laterally to measure the lateral pressure of the soil on the pile side. The specific parameters of the model pile are shown in (Table 1), where E and ν are the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the model pile, L is the length of the pile, R is the outer diameter of the pile, and θ is the pile tip angle.

Experimental sand

The sand adopts Chinese ISO standard sand with SiO2 content greater than 96%. The particle size distribution curve and physical and mechanical parameters of the sand are shown in (Fig. 3; Table 2). To simulate different foundation conditions, sand was layered and spread to a thickness of 800 mm using the sanding method in the model box. The working condition of standard sand containing pebble interlayer is to distribute pebbles with a particle size range of 5 mm to 30 mm in the depth range of 20 to 30 cm from top to bottom, and fill the rest of the depth range with standard sand. The filling weight is 1160 kg to maintain a relative density of about 0.75 for the sand sample22.

Test method

During the experiment, the process of pile penetration was simulated by segmented static pressure penetration. According to the research of Xiao et al.23, a lower pile penetration rate can improve the soil squeezing effect during pile penetration, and whether it is a continuous or segmented pile penetration method, the impact on the pile penetration characteristics and bearing capacity characteristics is relatively small. Therefore, this experiment adopted a constant pile penetration speed of 0.1 mm/s for segmented pile penetration. Considering the travel limitations of the actuator and actual construction conditions, pile penetration will be carried out in three stages, with a penetration of 200 mm each time. After each penetration is completed, the pile is left to stand for 30 min to achieve soil stability, and then the next pile pressing is carried out. Given the high uniformity and stability of the standard sand used in this study, the penetration process exhibits minimal variability under the same experimental conditions. Therefore, instead of conducting multiple penetration trials, we ensured repeatability by strictly controlling the experimental procedure and maintaining consistent test conditions. The burial location of the soil pressure gauge around the model pile is shown in (Fig. 4).

Analysis of test results

Pile penetration force analysis

The curve of pile penetration force changing with penetration depth is shown in (Fig. 5). The results show that when segmented pile penetration is carried out under standard sand conditions, the pile penetration force increases with the penetration of the pile, and the pile penetration force at each penetration node instantly drops to zero; When continuing to press the pile, the penetration force quickly recovers and rises again, and the rising slope is similar to the previous section, indicating that the variation law of penetration force in each section of the penetration process is basically the same23. In the standard sand with pebble interlayer condition, the variation curve of pile penetration force is roughly the same as that of pure standard sand condition in the stage of not contacting the pebble interlayer (before 2.0 × 103 s). But when the model pile comes into contact with the pebble layer, the force sharply increases, reaching the first peak of 2.2 kN (penetration depth of 286 mm). As the penetration depth increased to 308 mm, the pile penetration force briefly decreased to 1.69 kN, still higher than the standard sand of 1.36 kN at the same depth. After passing through the pebble interlayer, the growth rate of pile penetration force is similar to that of standard sand. Overall, the pile penetration force of the pebble interlayer is 1.3 times that of standard sand, with the highest point reaching 1.8 times.

Figure 6 shows the Q-S curves obtained from the graded static load experiments of two working conditions after pile penetration is completed. Refer to the Chinese “Code for Design of Building Foundation”24, for steep Q-S curves, the load value corresponding to the obvious inflection point is taken as the ultimate bearing capacity. In this study, the inflection points were identified based on the shape of the Q-S curves—where the slope of the curve increases rapidly after an initial relatively gentle segment—following the method recommended in the specification. The results show that the existence of a pebble interlayer improves the ultimate bearing capacity of a pile. The ultimate bearing capacity under pebble interlayer condition is 4.01kN, which is about 1.3 times higher than that under standard sand condition (3.02kN). The reason is that the pebble interlayer changes the distribution of pile side resistance and pile end resistance. The data support is described in Sect. 3.4.

Analysis of soil pressure around the pile during penetration process

Figure 7 shows the dynamic variation curves of lateral soil pressure at different depths and horizontal distances from the pile body at positions r = 1D, 3D, 5D, and 7D under two situations, as the penetration depth of the model pile increases. The horizontal axis clearly represents soil pressure (kPa), while the vertical axis represents penetration depth (mm). Subfigure (a) illustrates the lateral soil pressure distribution under standard sand conditions, whereas subfigure (b) corresponds to the standard sand with a pebble interlayer. Here, r denotes the horizontal distance between the measuring point and the side of the pile, D is the diameter of the model pile, and H represents the burial depth of the measuring point. Each subfigure includes a legend indicating the burial depth H for the measurements.

Under pure standard sand conditions, the lateral soil pressure at a certain point around the pile will significantly increase near the pile head, and then rapidly decrease after crossing the position. As shown in (Fig. 7a), when the pile penetrates to H = 150 mm, the soil pressure reaches its peak, which is approximately 12 kPa. And when the penetration depth exceeds 2D at that position, the soil pressure around the pile rapidly decreases. Similar phenomena have also occurred at other depths. This is because in the initial stage of pile penetration, the surrounding soil will be compacted first, and then its initial structure will be destroyed, resulting in overall shear failure, shallow buried soil uplift, and local soil loosening25,26, leading to a phenomenon similar to stress relaxation. In addition, the lateral soil pressure curve in (Fig. 7a) also indicates that under standard sand conditions, the lateral soil pressure caused by pile penetration will diffuse earlier than the pile head reaches the measuring point. For example, when the pile penetrates to a depth of H = 150 mm, the peak soil pressure occurs in the range of 85.31 mm to 125.6 mm; The peak soil pressure occurs at depths of 155.24 to 200 mm, 239.8 to 256.5 mm, and 365 to 425.9 mm when the pile penetrates to H = 250 mm, H = 350 mm, and H = 450 mm, respectively.

Under the standard sand pebble interlayer condition, there will be two peak values of lateral soil pressure at each depth (Fig. 7b). During the process of the pile head contacting the pebble layer, there will be an increase in lateral soil pressure at any depth in the underlying sandy soil layer. When the pile passes through the pebble layer and reaches about 300 mm, the lateral soil pressure intermittently decreases at different burial depths and pile distances. When the pile head approaches the depth of each measuring point, the lateral soil pressure will quickly rise again. After the pile head crosses the depth of each measuring point, the lateral soil pressure at each position will significantly decrease. This is because there is a significant difference in strength between the sand and pebble layers, and during the penetration process, the additional load generated by the pile head overcoming the ultimate bearing capacity of both layers on the underlying soil layer also varies greatly.

In the later stage of penetration, the soil pressure at the lateral 1D, 3D, and 5D positions at depths of H = 150 mm and H = 250 mm under standard sand conditions showed negative values; In the standard sand pebble interlayer condition, the soil pressure at positions 1D, 3D, 5D, and 7D with a burial depth of H = 150 mm is also negative in the later stage of penetration, with the most significant change at position 1D. The occurrence of this “negative soil pressure” phenomenon is mainly due to the fact that the lateral soil pressure in Fig. 7 is relative to the value before penetration. When the overlying pressure is low, the soil squeezing effect of the pile causes lateral displacement of the soil, leading to uplift and relaxation of the shallow buried soil, and reducing its compactness25,26; When the overlying pressure is high, the soil squeezing effect of pile penetration is more likely to cause additional stress to accumulate in deep soil, resulting in local shear failure.

Analysis of axial force and lateral friction resistance of pile body under load

Under vertical load, the mechanical transmission characteristics of pile foundation can be studied by analyzing the axial force of the pile body. Based on formulas (1) and (2), the lateral friction resistance and pile end resistance at each position of the pile body can be calculated segment by segment.

The calculation of pile axial force can be obtained through the following formula:

Among them, Qi represents the axial force of the pile body at the i-th section; Ec is the elastic modulus of the pile body, with a value of 200 GPa for this model pile; Ai is the cross-sectional area of the i-th section; εi is the strain value of the section.

The lateral frictional resistance of the pile can be calculated using the following formula:

Among them, qs is the average value of pile side friction resistance; L0 is the length of the pile body unit; D is the diameter of the pile; Qi−1 and Qi are the axial forces of adjacent pile units, respectively.

By using the above two formulas, the axial force at each position of the pile body can be calculated, as shown in (Fig. 8). The horizontal axis represents axial force (kN), and the vertical axis represents penetration depth (mm). The axial force was obtained based on strain measurements from gauges affixed along the model pile. It can be observed that the axial force decreases approximately linearly from the loading end to the pile tip under both working conditions. This linear decay trend is attributed to the controlled boundary conditions and relatively uniform side resistance in the laboratory model, as well as the use of average strain values over discrete intervals along the pile. While field tests often exhibit nonlinear axial force variations due to complex soil layering and progressive side resistance mobilization, the model test results reflect a simplified response representative of homogeneous or mildly stratified sandy soils. When analyzing the axial force of the pile, it was found that the axial force at each point of the pile increased almost linearly with the increase of load. For the working condition with pebble interlayer, when the pile head penetrates into the pebble interlayer at a depth of 200 mm to 300 mm, the axial force of the pile body rapidly decreases, which is significantly smaller than that in the pure sand working condition where the pile head penetrates into the same depth. This phenomenon is mainly attributed to the presence of pebble interlayer, which increase the friction resistance experienced by the pile.

Figure 9 presents the pile side friction resistance diagram. It can be seen that as the penetration load increases, the lateral friction resistance at various positions of the pile body shows an increasing trend. Under any level of load conditions, the lateral frictional resistance reaches its peak when the pile body penetrates to the middle and lower parts. This further proves what was mentioned in Sect. 2.2, that due to the high stress level and strength of the lower soil, the non-linear increase in lateral pressure caused by the soil squeezing effect due to pile penetration leads to significant lateral frictional resistance; When the pile body penetrates to the middle and upper parts, a large amount of soil around the pile becomes relatively loose due to lateral extrusion, resulting in lower stress levels and strength, leading to a decrease in lateral friction resistance. During the penetration process of sandy soil with pebble interlayer, it was found that the peak point of lateral friction resistance occurred at the point of penetration into the pebble interlayer. This indicates that the particle structure and morphology of the pebble interlayer have a significant impact on the lateral friction resistance of the pile. The soil at the pebble interlayer has higher friction strength, resulting in stronger lateral friction resistance response.

Analysis of resistance distribution during penetration process

Figure 10 shows the variation of pile side resistance and pile tip resistance with penetration depth (mm) under two conditions: (a) standard sand, and (b) standard sand with a pebble interlayer. The horizontal axis represents force (kN), and the vertical axis represents penetration depth (mm). Under standard sand conditions, the pile side resistance and pile end resistance almost increase linearly with the increase of penetration depth (Fig. 10a). The presence of pebble interlayer leads to local increases and fluctuations in pile end and side resistance, reflecting the significant impact of pebble interlayer on soil deformation and friction (Fig. 10b).

According to statistics, the percentage of pile end resistance and pile side resistance to the compressive pile force of the model pile under two working conditions was obtained, as shown in (Table 3). qu is the pile penetration force, qp is the pile end resistance and qs is the pile side resistance.

According to Table 3, the proportion of pile end resistance to compressive pile force for model piles in pure standard sand and standard sand with pebble interlayer is 68.8 and 59.4%, respectively; The proportion of pile side resistance to pile pressure is 31.3 and 40.6%, respectively. The results show that the pile end resistance dominates under both conditions27,28,29,30, but under the condition of pebble interlayer, the increment of pile end resistance is relatively small, and the increment of pile side resistance is relatively large under the condition of pebble interlayer.

Calculation of pile penetration resistance during penetration process

Meyerhof further improved Karl Terzaghi’s bearing capacity theory in 1951, stating that for foundations, the shear strength of the soil on both sides of the foundation should be considered, and the plastic equilibrium zone of the foundation soil should be extended to the soil above the burial depth of the foundation. While widely applied, Meyerhof’s formula calculates side resistance based on static soil pressure, which does not fully reflect the dynamic interaction between pile and soil during static pressure pile penetration—particularly in stratified soils with complex interlayers such as pebbles. To address this limitation, this study proposes a modified bearing capacity calculation formula based on Meyerhof’s theory. Using measured data from model tests, we introduced a dynamic correction factor λ into the original formula to account for the influence of evolving side friction during the pile penetration process. The correction factor was derived by fitting the experimental pile bearing capacity data from multi-layered soils to the theoretical predictions using MATLAB. Based on the soil characteristics and resistance variation patterns, a sine-function-based correction parameter ψ was adopted to model the variation of pile side resistance more accurately.

The basic assumption of the ultimate bearing capacity of Meyerhof’s foundation31 (Fig. 11) is as follows:

-

(1)

When the foundation is subjected to overall shear failure, the sliding surface usually extends to the surface and intersects with the ground at a point E, which is usually located at the edge of the foundation. The sliding surface consists of three parts: the straight line segment AC, the logarithmic spiral curve segment CD, and the straight line segment DE. The angle between the straight segment AC and the horizontal plane is (45°+φ/2), which is determined based on the internal friction angle of the soil.

-

(2)

When analyzing soil balance, equivalent stress σ0 and shear stress τ0 can be used to replace the interaction between the GF on the foundation side and the soil, as well as the soil weight of the GEF on both sides of the foundation. In the analysis, the soil of GEF was removed and replaced with an equivalent free surface GE, and its inclination angle β increased with the increase of foundation depth, reflecting the characteristic of soil stress state changing with depth.

-

(3)

Assuming that the normal pressure σa on the foundation side is distributed according to the static soil pressure, if the friction angle between the foundation side and the soil is δ, the average normal stress σa and τa acting on the foundation side can be calculated based on this.

In the formula: k0 is the static lateral pressure coefficient of soil; γ is the bulk density of the soil above the foundation bottom, kN/m ³; H is the burial depth of the foundation, m.

Based on the above assumptions, the ultimate bearing capacity of a homogeneous foundation under central load is obtained for a strip foundation. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula: c is the cohesive force of the soil, σ0 is the equivalent stress on the GE plane, kPa; B is the width of the strip foundation, H is the burial depth of the foundation, m; The bearing capacity coefficients Nc, Nq, and Ny are obtained using Eqs. (7), (8) and (9), respectively. These load-bearing components are all related to the internal friction angle φ, inclination angle β, and η, where η is influenced by the shear strength utilization coefficient m on the “equivalent free surface” The relationship between Nc, Nq, and Ny with φ, β and m can be found in (Fig. 12).

The Meyerhof’s ultimate bearing capacity calculation formula based on strip foundation can be extended to circular foundation, that is

In the formula, R is the pile diameter, m.

During the process of static pressure pile penetration, the dynamic shear force applied by the pile body may lead to soil erosion and shear failure. This failure mechanism is similar to Meyerhof’s analysis of shallow foundation shear failure. However, Meyerhof believes that when a deep foundation such as a pile foundation reaches failure, its failure zone is limited to a certain range inside the foundation. In this case, the ultimate bearing capacity qu of the foundation can still be calculated according to Eq. (10), but the bearing capacity coefficients Nc, Nq, and Ny in the equation should be taken within the range of 60°<β < 90° in (Fig. 12)32. According to the analysis in Sect. 2.2, the lateral frictional resistance of the pile will dynamically change with the depth of pile insertion during the dynamic pile insertion process. However, in the Meyerhof’s ultimate bearing capacity formula for foundations, the pile side resistance is calculated based on static soil pressure. To reflect this dynamic behavior, a depth-dependent correction factor λ was introduced to adjust the static lateral earth pressure σ0 in the original formula. This factor was empirically derived from model test data using MATLAB’s curve fitting tool and expressed as:

In the formula: The functional form of λ was chosen for its ability to capture the nonlinear growth trend of pile-soil interface friction with increasing depth H. Where a, b and c is a constants, and its value is related to the soil coefficient, pile parameters, and pile penetration parameters; H is the depth of penetration, mm.

The soil used in this experiment is IOS standard sand, which is non cohesive soil. Therefore, c = 0, that is

Ignoring the influence of geological and other environmental factors on pile penetration resistance, this study uses the above formula for fitting calculation. Fit parameters a=-0.6361, b=-0.4609 and c = 2.286 in this experiment. As shown in (Fig. 13), the horizontal axis represents the pile penetration force qu (kN), and the vertical axis represents the penetration depth (mm) (Note that the coordinate axes in Figs. 14 and 15 follow the same convention). Under standard sand conditions, the deviation between the calculated pile penetration resistance and the average measured pile penetration force in the experiment is about 1.5%, indicating a good fitting effect. In contrast, the difference between the calculated values obtained using Meyerhof’s ultimate bearing capacity formula and the experimental results exceeds 15%, mainly due to the calculation deviation of Meyerhof’s formula when dealing with static loads. This experiment focuses on the changes in pile penetration resistance during the pile penetration process. Considering factors such as dynamic response, a correction factor is introduced, and the revised calculation formula has a better estimation effect on pile penetration resistance.

To verify the applicability of the proposed fitting formula in engineering practice, field test data from a trial PHC pile at a construction site in the Dajiangdong Industrial Cluster Area of Hangzhou were analyzed33. The pile penetration resistance at different depths was estimated using Formula (13), and the results are presented in (Fig. 14). The on-site soil profile consists of multiple layers, including cohesive soil, silt, and interbedded sandy silt. Using silt as the bearing layer of the pile foundation, the tip resistance is 1600 kPa and the lateral friction force is 28 kPa. The comparison shows that Meyerhof’s formula tends to underestimate the pile penetration force, whereas the proposed correction formula provides a closer match to the field-measured values. This suggests that the modified formula, derived from standard sand foundation conditions, exhibits reasonable applicability even in slightly varying stratigraphic conditions.

In practical engineering, the foundation is often composed of multiple soil layers stacked together, rather than a single stratum. Therefore, for layered foundations, a single correction factor is no longer applicable and a new correction factor that is suitable for multi-layer soil conditions needs to be determined. This experiment takes into account this practical situation and specially sets up a working condition containing a pebble interlayer. It is worth noting that the correction parameters proposed in this study are based on a uniform pebble gradation. In this case, there is a significant difference in strength between different layers, so a correction factor applicable to multi-layer soils, especially soil layers with significant strength differences (such as pebble interlayer), is introduced. To determine this correction factor, we used the Curve Fitting Tool tool in Matlab software to fit the model test data. Specifically, we fitted the bearing capacity data of the multi-layered soil foundation obtained from the experiment with the values calculated according to the Meyerhof’s bearing capacity formula. Considering the periodic or oscillatory nature of stress transfer and mobilization in layered media, a sine function model was selected to represent the variation in resistance with depth. The sinusoidal form allows the correction to capture the alternating influence of soft and stiff soil layers, and accommodates the nonlinear, wave-like pattern of force redistribution observed during penetration through stratified foundations. The fitting parameter ψ form is as follows:

In the formula: i is the number of items; ai, bi, ci is the constant, its value is related to the soil coefficient, pile parameters, and pile penetration parameters.

Using the Curve Fitting Tool tool in Matlab, import standardized experimental data, select a sine function model, and perform nonlinear least squares fitting. During the fitting process, the software automatically adjusts parameters ai, bi, ci to minimize the error between the experimental data and the calculated values using the Meyerhof’s formula. We simplified the calculation cost by selecting the appropriate parameter i = 2 while ensuring accuracy. The obtained fitting parameters are a1 = 1.897, b1 = 5.181, c1=−0.447, a2 = 0.2688, b2 = 26.78, c2=−0.8264. In Fig. 15, the test and calculated values of pile penetration force under the condition of pebble interlayer are presented. The fitted values obtained by using the above method are basically consistent with the experimental values, with a difference of less than 10%. Therefore, these fitting parameters can be used for the calculation of pile penetration resistance in pebble interlayer foundations.

To further validate the applicability of the proposed fitting formula under field conditions, in-situ test data from the construction of a 10-story frame-shear structure in Fujian Province were analyzed34. The site, located on an alluvial-pluvial plain, featured a stratigraphic sequence with a 0.9–3.0 m-thick gravelly pebble layer of medium density overlain by silty clay and underlain by residual gravelly clay. The project employed PHC piles designed to penetrate the pebble interlayer. The revised formula was applied to predict the peak penetration resistance for the 1.25 m-thick pebble interlayer (2.5Dpile), yielding a value of 3742 kN (predicted) versus the measured 3930kN (actual), demonstrating a deviation of 5%. It is worth noting that the field strata are different from the unified sand and pebble model in the laboratory (Fig. 16). The difference lies in the homogeneity of the foundation soil and the relatively flat pebble interlayer. Despite these differences, the performance of the formula highlights its adaptability in estimating the pile driving force penetrating through pebble interlayers.

To facilitate practical engineering application, a step-by-step implementation procedure for the proposed correction model is illustrated in (Fig. 17). This flowchart not only provides a simplified overview of the key steps—ranging from initial soil investigation, parameter fitting, correction factor calculation, to final application in pile design—but more importantly, it highlights the iterative nature of the correction model. As shown in the diagram, the model allows for continuous integration of newly collected site data and working conditions into the correction factor fitting process. This adaptive mechanism enables ongoing refinement and optimization of the model, improving its predictive accuracy and extending its applicability across diverse geological scenarios. Over time, as the dataset expands, the correction model becomes more robust, making it a practical and scalable tool for real-world pile foundation design.

Conclusion

This study employed static pressure pile penetration model tests to investigate the pile force, lateral soil pressure, and stress characteristics of the pile body during penetration in both pure sandy soil and sandy soil with a pebble interlayer. Based on Meyerhof’s theory for ultimate bearing capacity, a new method for estimating the dynamic pile penetration resistance was developed. The following main conclusions were drawn:

-

(1)

The presence of a local pebble interlayer significantly increases the penetration resistance of static pressure piles in sandy soil foundations, making pile installation more difficult. Experimental results indicate that a pebble layer with a thickness of 2.5 times the pile diameter can increase the pile driving force by up to 1.8 times, with an average increase of 1.3 times. In both soil conditions, the pile tip resistance plays a dominant role. However, in the presence of a pebble interlayer, the pile side resistance is also notably enhanced.

-

(2)

The lateral soil pressure around the pile does not increase linearly with the depth of pile penetration. In homogeneous sandy soils, the soil pressure at a given depth sharply increases when the pile tip approaches due to the soil squeezing effect, then rapidly decreases once the pile passes that point due to unloading caused by the failure of surrounding soil. When the pile tip passes through the pebble interlayer, it significantly increases the lateral soil pressure in the underlying soil strata.

-

(3)

Based on the Meyerhof’s ultimate bearing capacity calculation principle, a calculation model for calculating the pile penetration resistance of uniform and pebble interbedded sandy soil foundation has been developed. Comparison with experimental data shows that the proposed model improves prediction accuracy and can be effectively used for estimating the penetration resistance of static pressure piles.

Limitations

This study confirms the effectiveness of our approach in predicting the behavior of static pressure piles in sandy soils with pebble interlayers. While the correction factors improve accuracy, their applicability could be further enhanced with broader soil conditions and expanded datasets. Future research will focus on refining these factors through additional experiments and field validations to strengthen their predictive reliability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mengqiu, F. Research on the design and construction of pile foundation of complex karst geological bridge. Guangdong Archit. Civil Eng. 30 (12), 120–123 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Effect of permafrost degradation on seismic vulnerability of bridge pile foundations along Qinghai-Tibet railway. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 45 (03), 953–965 (2023).

Zhao, Z. & Qu, X. Study on the influence of subgrade filling of composite foundation on bridge pile foundation. Highway 67 (08), 92–97 (2022).

Jiang, Y. & Huang, G. Study on pile tip effect of jacked pile in sand. Build. Sci. 32 (11), 74–82 (2016).

Shiwei Liu, X. et al. Application of miniature FBG-MEMS pressure sensor in penetration process of static pressure pile. J. Optoelectron. Laser 31 (8), 806–813 (2020).

Hai Lin, L. et al. Interaction between laterally loaded pile and surrounding soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 141, (4) (2015).

Jingpei, L. I. et al. Study of mechanical properties of soil around jacked piles considering variable consolidation coefficient. Rock. Soil. Mech. 37 (3), 679–686 (2016).

Zhu, H. et al. Large-scale model experimental study on cyclic penetration process and vertical bearing characteristics of open-ended pipe piles. Rock. Soil. Mech. 45 (11), 3173–3184 (2018).

Li, B. J., Zang, H. M. & Lv, G. H. Statistical analysis of bored piles with pile-bottom post grouting [C]. 4th International Conference on Mechanical Materials and Manufacturing Engineering (MMME) 645–649. (2016).

Du, Y., Zhang, P. & Zhang, J. Mechanical response and control measures of pile foundations under close-range shield tunneling in water-rich sandy pebble strata. Adv. Civil Eng. (1), 4364716. (2024).

Min Chen. Experimental study on load transfer of large-diameter drilled piles in deep soft soil area. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 12 (5), 1205–1210 (2016).

Nianwu Liu, X. & Gong, Feng, Y. U. Vertical bearing capacity of large-diameter bored pile. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Technol.) 49 (4), 763–768 (2015).

Jun Wang, Tian, J. I. N. et al. Experimental study of post-grouting effect of piles installed in inhomogeneous pebble bearing layer. Rock. Soil. Mech. 45 (5), 1321–1333 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Study on the diffusion law of grouting slurry at the pile tip of bored piles in gravel pebble layers. Buildings 14 (8), 2555 (2024).

Pengzhen Lin, J. & Ma Design of backfill materials for driving steel sheet piles and pile forming tests in gravel layer. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 44 (1), 187–193 (2022).

Kang, J. et al. Vertical bearing capacity of driven PHC piles in the Chengdu gravel foundation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 32 (S2), 107–110 (2010).

Junlong Liu. Research on bearing capacity behavior of precast concrete piles in gravel stratum. Rock. Soil. Mech. 29 (5). (2008).

Jilin Liu. The pile driving pressure and the ultimate bearing capacity of pile driving by static force. Ind. Constr. 35 (2), 64–68 (2005).

Huang, T. Side friction of drilled piles in cobble layers. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 24 (2), 8 (2016).

Jianping Jiang, G., Gao, B. & Gu Behavior of load transfer of large diameter belled pier in sandy cobble layer. Eng. Invest. Invest. 31 (5), 5–7 (2003).

Guoqiang Yang, L. et al. Reliability analysis of vertical bearing capacity of single manual hole digging pile on sand and gravel foundation. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. (Natl. Sci. Ed.) 29 (6), 1020–1023 (2010).

Haijun Liu, Z. et al. Analysis of rebound and recompression characteristics of jacked piles in a sand foundation. J. Build. Struct. 43 (07), 301–310 (2022).

Zhaoran, X. et al. Experimental investigation on resistance and response of jacked model piles in sand. J. Build. Struct. 43 (11), 294–302 (2022).

GB 50007. Code for design of building foundation [S]. (2011).

Jianzhong Ye, J., Zhou, B. & Han Numerical simulation of particle flow in pile sinking process based on discrete element theory. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. (S1), 3058–3064. (2007).

Luo, Z. et al. Research on displacement field of soil squeezing by single pile under static pressure considering pore pressure dissipation. Chinese J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 33 (S1), 2014.s1.025 (2014).

Guangjin Wang, C. et al. Experimental study of coarse particle content on fracture and strength characteristics of granular rock and soil particles. Rock. Soil. Mech. 30 (12), 3649–3654 (2009).

Teng Zhang. Research on Penetration Process and Bearing Characteristics of medium-static Pile with Different Soil Properties [D] (Qingdao University of Technology, 2023).

Guangjin Wang, C. et al. Numerical simulation of coarse-grained soil triaxial test and preliminary study on particle structure of sample. Rock. Soil. Mech. 32 (02), 585–592 (2011).

Li, Z. & Xing, Y. Effects of dry density and fine particle content on shear strength of sand, pebble, and pebble. Rock. Soil. Mech. (12), 2255–2260. (2006).

Meyerhof, G. G. The ultimate bearing capacity of foundations. Geotechnigue 22 (4), 301–331 (1951).

Zongze Yin, B. et al. Geotechnical Principles [M] (China Water Resources and Hydropower, 2012).

Fang, Y. et al. Resistance analysis of static pile driving under sandy soil in qiantang new area, Hangzhou. Build. Struct. 53 (S1), 2678–2681 (2023).

Shuchen Chen. Estimating and verifying the pressure for driving static pressure piles penetrating cobble stratum. J. Chongqing Jianzhu Univ. 23 (4), 123–126 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lanzhou University of Technology for providing the test site and all the students for their help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Field test. C.Y.:Field test, Writing—original draft. X.M.: Formal analysis. F.Z.:Writing—review and editing. J.L.:Investigation, Field test. M.D.: Field test. W.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors Xiannian Zhou, Chengyun Yang, Xiaojie Ming, Mi Dai and Weihe Lu, work for the overseas branch of CCCC Road and Bridge Construction Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Yang, C., Ming, X. et al. Mechanical characteristics and calculation method of static pressure pile installation for PHC pipe piles in sandy soil foundation with pebble interlayer. Sci Rep 15, 13756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98127-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98127-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A comprehensive study on damage prediction of pile foundations of inclined high rise buildings and the effect of compaction grouting

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

An analytical solution for load transfer mechanism of Plum blossom pile foundations

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Scaled Model Testing of Open-Ended Concrete Pipe Piles in Loess: Effects of Penetration Method and Pile Diameter

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2025)