Abstract

Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning causes significant mortality and hypoxic brain injury. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) may reduce delayed neurological sequelae, but poor outcomes persist. A model for predicting outcomes early after hospital admission is crucial for guiding care and early rehabilitation. In this study, we aimed to develop a clinical scoring model to predict poor outcomes in acute CO poisoning cases. The study included 176 patients aged ≥ 15 years with acute CO poisoning who were transported for HBOT between 2012 and 2023, after excluding those aged < 15 years and those in cardiac arrest on arrival. Acute CO poisoning was defined as CO exposure or COHb > 5% (> 10% for smokers). HBOT involved ≥ 1 session at 2.8 absolute atmospheres for 60 min. Predictors of poor outcomes included age, GCS < 13, burns and low C-reactive protein levels. The ABCG score (age, burns, CRP, GCS) demonstrated strong discriminative ability, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.917, sensitivity of 0.852 and specificity of 0.828. The ABCG score accurately predicts poor outcomes in acute CO poisoning and supports early intervention and treatment planning. External validation and broader application are needed for clinical adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO), a colourless and odourless gas, is one of the leading causes of poisoning-related fatalities worldwide1,2. The management of CO poisoning is a significant clinical challenge. CO poisoning can lead to hypoxic brain injury and death, with severe cases potentially benefiting from early intensive care to improve outcomes3. CO forms carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb) by binding to haemoglobin with an affinity 250 times greater than that of oxygen, causing significant tissue hypoxia even with minimal inhalation4. Furthermore, CO binds to myoglobin and mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase, restricting oxygen delivery and causing damage to neuronal cells via lipid peroxidation5,6.

Organs with high metabolic rates, such as the heart and brain, are particularly vulnerable, making death and neurological sequelae common complications of CO poisoning7,8. Neurological sequelae, such as delayed neurocognitive sequelae (DNS)—characterised by memory impairment, reduced attention span and emotional instability—may occur even days to weeks after an apparent initial recovery9. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) has been widely used to improve tissue oxygenation and reduce the incidence of DNS10. However, even with HBOT, DNS occurs in approximately 18% of cases, highlighting the need for a reliable prediction model that facilitates the early identification of high-risk patients11.

Previous studies have reported that age, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, lactate levels and COHb levels are associated with patient outcomes12,13. However, findings regarding the predictive power of these factors remain inconsistent. In particular, COHb levels have shown limited predictive utility because of variability caused by oxygen therapy and the time elapsed before measurement14. Against this backdrop, developing a simple yet accurate clinical scoring model that can be applied in the initial transport stage is imperative. This study aimed to develop and validate a practical and reliable scoring model to predict poor outcomes in cases of acute CO poisoning, facilitating better early intervention and optimised treatment strategies.

Methods

Subjects

The study targeted cases of acute CO poisoning in patients aged ≥ 15 years who were transported to a tertiary emergency medical centre in Tokyo capable of providing 24-h HBOT, from 2012 to 2023. Cases in cardiac arrest on arrival were excluded. This is the criterion established at our institution for safely administering HBOT and is also a requirement stated by the ethics committee. Therefore, we set the inclusion criteria at 15 years or older.

Definition

Acute CO poisoning was diagnosed based on a clear history of CO exposure or carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb) levels > 5% (> 10% for smokers). Reported COHb values were the initial test results from the referring hospital, or the first measurement obtained at our facility. There was considerable variability in the time elapsed and oxygen treatment provided before blood sampling for COHb measurement. HBOT was initiated for patients with temporary or prolonged impairment of consciousness, neurological signs, cardiovascular dysfunction, severe acidosis or estimated COHb levels exceeding 25% (accounting for half-life calculations based on transport time and oxygen therapy). The half-life of COHb was defined as 5 h under ambient air and 70 min under 100% oxygen administration. The estimated COHb level at the exposure site was calculated based on the exposure duration and transport time17.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

A type II hyperbaric oxygen chamber (P-2200S, Barotech Hanyuda Co.) designed for multiple patients was used. The protocol involved an oxygen mask with FiO₂ of 1.0 and a flow rate of 10 L/min, a pressurisation period of 15 min, 60 min at 2.8 absolute atmospheres and a depressurisation period of 15 min. The chamber was operational 24 h per day, with a treatment duration of 60 min per session, 7 days a week, and a total of 10 sessions, which were performed during a single hospitalisation.

Burn

The presence of burns was defined as second-degree burns covering 1% or more of the body surface area at the time of arrival.

Data collection

Data collected included demographic information (age, sex), vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate), initial consciousness level (GCS), duration of CO exposure, transport time and mode of transport (direct or transfer). Arterial blood gas analysis was performed immediately upon hospital arrival to measure pH, COHb, lactate levels, base excess (BE), complete blood counts and biochemical markers such as CRP (C-reactive protein). Head computed tomography scans were performed for all cases on the day of arrival. Exposure duration was assessed based on history, but this was difficult to determine in cases with unclear information.

Primary outcome measures

A Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 5 at discharge was considered a favourable outcome, while a GOS of ≤ 4 was classified as a poor outcome. This evaluation was made at discharge by multiple physicians from the primary care team.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using StatFlex Plus (ViewFlex, Inc.). P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages and compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation or as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and were analysed using the t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. To address multicollinearity, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated, and variables with VIF > 10 were considered highly collinear. To evaluate the association between each explanatory variable and the outcome, univariable logistic regression analyses were first performed. Variables that were significant in the univariable analyses were then entered into a multivariable logistic regression analysis considering multiple explanatory variables simultaneously in order to identify independent predictors of poor outcomes. The predictive probabilities obtained from these models were used to evaluate performance, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were created to assess discriminative ability. The optimal cutoff point was determined using the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity − 1), and sensitivity and specificity were calculated at this cutoff. A scoring model based on coefficients from the multivariable logistic regression model was developed and validated internally using the patient data in this study.

Ethics declarations

This prospective observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Medical School (approval number: B2023654). All patients provided written informed consent for participation in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects. Additionally, the authors adhered to the policies of Scientific Reports, as part of the Nature Portfolio journals, throughout the preparation, submission, and publication processes. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Patient background

From January 2012 to December 2023, 187 patients with carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning were admitted to our facility. After excluding 4 patients under 15 years of age and 7 patients in cardiac arrest on arrival, a total of 176 cases were included in the analysis. Overall, the median age was 46.5 years (IQR 30.0–64.0), and there were 64 male and 112 female patients. The median GCS on admission was 15 (IQR 10–15).

The most common cause of CO poisoning was charcoal burning, accounting for 71 cases (39.4%), all of which were suicide attempts. This was followed by fire-related incidents (70 cases, 38.9%) and accidental or other causes (39 cases, 21.7%). The median duration of CO exposure was 70 min (IQR 17.5–180). HBOT was administered in 140 patients (77.8%) (Table 1). Neurological outcomes measured by the GOS indicated that 122 patients had favourable outcomes (GOS 5).

When comparing good and poor outcome groups, significant differences were observed in age, GCS, BE, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, D-dimer level, heart rate, blood glucose, lactate level, white blood cell count, aspartate aminotransferase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin (Alb), C-reactive protein (CRP) and presence of burns (Table 2). On the other hand, no significant differences between the outcome groups were found in the initial COHb level, the presence or absence of HBOT administration, or the duration of exposure.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis

To evaluate the association between each explanatory variable and the outcome, univariable logistic regression analyses were first performed (Table 3). Variables that were significant in the univariable analyses were then entered into a multivariable logistic regression analysis considering multiple explanatory variables simultaneously in order to identify independent predictors of poor outcomes. Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified age (odds ratio [OR] 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07, P = 0.003), presence of burns (OR 3.99, 95% CI 1.51–11.11, P = 0.006), GCS < 13 (OR 4.62, 95% CI 2.63–8.68, P < 0.001), and CRP level (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.19–2.52, P = 0.006) as independent predictors of poor outcomes. Abnormal blood pH was not significantly associated with poor outcomes (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.43–3.49, P = 0.666). Low albumin levels were also not significantly associated with poor outcomes (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.09–1.10, P = 0.076) (Table 4).

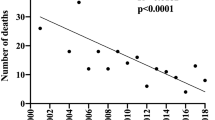

ROC analysis and scoring model

The predictive performance of the multivariable logistic regression model was evaluated using ROC analysis. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.917 (95% CI 0.87–0.96), indicating excellent discriminative ability (Fig. 1). The optimal cutoff point, determined using the Youden index, resulted in sensitivity of 0.852 and specificity of 0.828. The cutoff value was 1.553. To enhance the practicality of the predictive model, a scoring system (ABCG score) was developed based on the regression coefficients:

-

Age: continuous variable

-

Burns: absent (0), present (1)

-

CRP: continuous variable

-

GCS: GCS ≥ 13 (0), GCS 9–12 (1), GCS ≤ 8 (2)

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of the score model in the derivation and validation cohorts. AUC, 0.917; sensitivity, 0.852; specificity, 0.828. ABCG indicates the prediction score calculated from, age, presence of burns, C-reactive protein, and the Glasgow Coma Scale. The cutoff value was 1.553.

The score was calculated using Eq. (1):

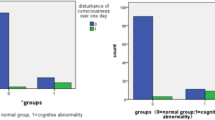

This scoring model was applied to all patients, allowing stratification of risk levels. Patients with higher scores were found to have an increased risk of poor outcomes (Fig. 2).

The score was calculated using the following equation: \({\text{Score }} = \, \left( {{\text{Age }} \times \, 0.0{4}} \right) \, + \, \left( {{\text{Burns }} \times { 1}.{3}0} \right) \, + \, \left( {{\text{GCS }} \times { 1}.{6}0} \right) \, + \, \left( {{\text{CRP }} \times \, 0.{6}0} \right).\)

Estimated probability of poor outcomes in patients with acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Age: continuous variable. Burns: absent (0), present (1). C-reactive protein (CRP): continuous variable. Glasgow Coma Score (GCS): GCS ≥ 13 (0), GCS 9–12 (1), GCS ≤ 8 (2).

Discussion

In this study, we developed a simple yet accurate clinical scoring model to predict poor outcomes in patients with acute CO poisoning. This model, based on 4 clinical factors—age, presence of burns, CRP, and GCS—enables rapid risk assessment soon after arrival. The AUC was 0.917 (95% CI 0.87–0.96), demonstrating excellent discriminative ability and confirming the model as a practical and reliable predictive tool.

Previous reports generally suggest that in cases of CO poisoning, if the COHb level is within a certain range and there are no symptoms or organ dysfunction, hospitalisation is not indicated, and observation for only a few hours is required15. In the present study, by utilising a scoring system, we demonstrate that poor outcomes can be predicted regardless of the initial COHb level by calculating a score based on four factors. This makes the scoring system a useful tool for determining the need for hospitalisation as well as admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) or another high-acuity department. The average hospitalisation period in our study was 11.6 days. Even within this relatively short period, when the score exceeded 3, the proportion of patients with a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of 4 or lower reached 76.6%. Therefore, even in cases where there are no initial symptoms, this scoring system provides strong justification for both definite hospitalisation and ICU admission. Conversely, even in cases with lower scores, patients with a score of 1 or higher should be considered for definite hospitalisation and careful observation. Unlike past reports that primarily relied on COHb levels, this scoring system allows for rapid assessment using only initial clinical evaluations and blood tests, making it useful for determining the need for hospitalisation and for deciding which hospital unit or department the patient should be admitted to in the early phase of treatment. Hampson et al. have highlighted associations of older age and impaired consciousness with poor prognosis, consistent with our findings2,16,17. Additionally, by identifying burns as strong predictors of poor outcomes, we provide new insights not extensively addressed in prior studies.

Interestingly, the initial COHb level and duration of CO exposure did not significantly influence outcomes in this study4,18,19. While earlier research suggested these factors as important predictors, variability in COHb levels after oxygen therapy and individual differences may account for the discrepancy20,21. This study, conducted at a single centre with a retrospective observational design, included a limited number of patients. Therefore, multi-centre collaborative studies are required to generalise the results. Furthermore, validation using larger datasets is essential5,8,22. The ABCG score facilitates rapid risk stratification in clinical settings, promoting early intervention for high-risk patients, optimising treatment strategies and potentially improving outcomes. Future studies should focus on external validation and further refinement of the model23.

This study has several limitations. The single-centre retrospective observational design potentially limited its external validity. Regional or institutional differences in the prevalence and treatment approaches for CO poisoning may not be fully reflected in the findings16. Consequently, the results may not entirely represent the clinical characteristics of patients with CO poisoning in other regions. Additionally, the relatively small sample size of patients with CO poisoning who were admitted to the ICU may have limited the statistical power. GOS was used as an outcome assessment tool because of its simplicity, as it does not require special equipment or specialized training and can be assessed in a short amount of time.

Although GOS is a simple and suitable tool for assessing acute-phase outcomes, it cannot evaluate the risk of delayed neuropsychiatric syndrome, which can manifest weeks to months after CO poisoning. Even if a patient has a GOS score of 5 at discharge, there remains the possibility of subsequently developing cognitive impairment, memory dysfunction, or psychiatric symptoms. Consequently, the neurotoxic effects and higher-order brain dysfunction associated with CO poisoning may be underestimated. Blood levels of NSE and troponin, which have been reported to be associated with CO poisoning and outcomes, were not measured in this study. Therefore, these could not be assessed. This introduces certain constraints in drawing conclusions about the association between brain injury and poor outcomes. Furthermore, lack of data on environmental CO concentration limited the ability to assess the impact of exposure conditions on outcomes24. Additionally, insufficient information on the duration of exposure and environmental conditions hindered the detailed exploration of their influence on outcomes. To address these limitations, multi-centre studies and large-scale prospective data collection are necessary. Additionally, the development of new predictive models incorporating MRI and biomarkers and the validation of the external applicability these models through randomised controlled trials are areas for future exploration15,17,25.

Conclusion

This study developed a simple and accurate scoring model, called the ABCG score, to predict poor outcomes in patients with acute CO poisoning. The model enables rapid risk assessment during the initial transport phase, providing a tool to support early decision-making and timely interventions for critically ill patients. By identifying high-risk patients, the ABCG score can facilitate family discussions and appropriate treatment choices. It also allows for intensive care to enhance the prognosis of patients who have favourable predicted outcomes, while early symptom management and rehabilitation planning can be initiated for patients with poor predicted outcomes.

This model is expected to contribute to the early diagnosis of CO poisoning, improved treatment efficiency and comprehensive care for patients and their families. The application of the ABCG score demonstrates its potential for accurate outcome prediction in patients with CO poisoning, offering practicality in clinical settings. Future validation studies are needed to expand the model’s applicability and clinical utility.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Weaver, L. K. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa013121 (2002).

Hampson, N. B. & Weaver, L. K. Carbon monoxide poisoning: New incidence for an old disease. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 34, 163–168 (2007).

Goldstein, M. Carbon monoxide poisoning. J. Emerg. Nurs. 34, 538–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2007.10.013 (2008).

Hardy, K. R. & Thom, S. R. Pathophysiology and treatment of carbon monoxide poisoning. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 32, 613–629. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563659409017967 (1994).

Thom, S. R. et al. Stimulation of perivascular nitric oxide release by carbon monoxide in rat brain. J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 2193–2199. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00745.2003 (2003).

Ernst, A. & Zibrak, J. D. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N. Engl. J. Med. 339, 1603–1608. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199811263392207 (1998).

Prockop, L. D. & Chichkova, R. I. Carbon monoxide intoxication: An updated review. J. Neurol. Sci. 262, 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.037 (2007).

Mathieu, D., Mathieu-Nolf, M. & Wattel, F. Randomized prospective study comparing the effect of HBO therapy versus normobaric oxygen therapy in CO poisoning. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 23, 15–25 (1996).

Lee, H. C., Kuo, T., Chen, Y. C., Lin, H. C. & Lin, C. S. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on long-term prognosis in patients with carbon monoxide poisoning. Neurology 90, e2079–e2088. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005681 (2018).

Rose, J. J. et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning: Pathogenesis, management, and future directions of therapy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 195, 596–606. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201606-1275CI (2017).

Hampson, N. B. Use of the clinical practice guidelines in carbon monoxide poisoning management. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 17, 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70056-5 (1999).

Sert, E. T. et al. Acute brain injury detected by MRI predicts poor outcomes in carbon monoxide poisoning. Acta Neurol. Belg. 121, 901–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-021-01617-2 (2021).

Weaver, L. K. & Hopkins, R. O. Cognitive sequelae in carbon monoxide poisoning. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 32, 101–105 (2005).

Kao, L. W. & Nañagas, K. A. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 22, 985–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2004.07.004 (2004).

Weaver, L. K. Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1228–1234. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199910143411606 (1999).

Hampson, N. B. & Piantadosi, C. A. Predicting long-term cognitive sequelae following carbon monoxide poisoning. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 39, 851–856 (2012).

Hardy, K. R. & Thom, S. R. The pathophysiology of carbon monoxide poisoning and its implications for therapy. Crit. Care Clin. 8, 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0704(18)30662-4 (1992).

Moon, R. E. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 1517–1520. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199405263302106 (1994).

Weaver, L. K. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for carbon monoxide poisoning. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 36, 405–409 (2009).

Hampson, N. B. Pulse oximetry in severe carbon monoxide poisoning. Chest 114, 1036–1041. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.114.4.1036 (1998).

Thom, S. R. Antagonism of carbon monoxide-mediated brain lipid peroxidation by hyperbaric oxygen. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 105, 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-008X(90)90268-R (1990).

Tobias, J. D., McKee, C. & Smith, B. Pediatric carbon monoxide poisoning: Factors predicting poor outcomes. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 26, 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181ea6c27 (2010).

Mathieu, D. Carbon monoxide poisoning: Neuropsychological and neurological impact. Ann. Emerg. Med. 16, 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(87)80432-7 (1987).

Annane, D. et al. Mechanisms and consequences of carbon monoxide toxicity: Insights into therapy. Intensive Care Med. 42, 733–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4254-z (2016).

Piantadosi, C. A. Carbon monoxide poisoning: Advances in prevention and treatment. Annu. Rev. Med. 53, 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103825 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. This manuscript received English-language editing from ThinkSCIENCE, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hidetaka Onda: Conceptualisation; Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Funding Acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project Administration; Resources; Validation; Visualisation; Writing—Original Draft Preparation; Writing—Review and Editing. Shoji Yokobori: Supervision; Writing—Review and Editing. Kenta Shigeta: Data Curation, Review and Editing. Naoki Tominaga: Data Curation, Review and Editing. Nodoka Miyake. Data Curation, Review and Editing. Mizuki Kojima: Data Curation, Review and Editing. Takuya Nishino: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Onda, H., Nishino, T., Kojima, M. et al. A scoring system with high predictive performance for poor outcomes in acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Sci Rep 15, 14491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98162-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98162-1