Abstract

This study aims to utilize Color Doppler Ultrasound to collect blood flow parameters of the medial circumflex femoral artery and explore the changes in blood flow in osteonecrosis of the femoral head, providing objective indicators for clinical assessment and prognosis. Color Doppler Ultrasound was used to examine the medial circumflex femoral artery in 30 patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head (52 hips: ARCO Stage I—2 hips, Stage II—24 hips, Stage III—24 hips, Stage IV—2 hips) and 30 healthy controls (57 hips). Arterial diameter and blood flow parameters [peak systolic velocity, resistance index, pulsatility index] were collected and analyzed for vascular and blood flow characteristics in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. (1) Compared with the healthy group, the osteonecrosis group showed significantly lower peak systolic velocity and resistance index, while no significant differences were observed in arterial diameter and pulsatility index. (2) Arterial diameter in Stage I was significantly larger than in Stages II, III, and IV, with no significant differences observed among Stages II, III, and IV. Peak systolic velocity, resistance index, and pulsatility index all significantly decreased with disease progression from Stage I to Stage IV, but no significant difference in pulsatility index was found between Stages II and III. (3) There was no significant difference in arterial diameter between the non-collapsed and collapsed groups; however, peak systolic velocity, resistance index, and pulsatility index were all significantly lower in the collapsed group compared to the non-collapsed group. (1) The alterations in blood supply in femoral head necrosis primarily manifest as changes in blood flow parameters. (2) Vascular morphology and blood flow parameters could potentially be useful indicators for assessing the progression of femoral head necrosis. (3) Changes in blood flow parameters may provide valuable insights into the risk of femoral head collapse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head (ONFH) is a pathological condition marked by the death of bone tissue due to insufficient blood supply, potentially leading to the collapse of the femoral head and debilitating arthritis1. This condition predominantly affects young to middle-aged adults and can severely impact mobility and quality of life. The incidence of ONFH varies, but it is notably prevalent among patients undergoing high-dose corticosteroid treatment or those with significant alcohol consumption2.

The pathogenesis of ONFH is multifactorial, with disruption of blood supply being a key factor. The medial circumflex femoral artery (MCFA) provides the main vascular supply to the femoral head and neck, and its disruption leads to ischemia and bone necrosis2. While pathology can occur distal to the MCFA, particularly in the sub-synovial intracapsular ring, tracing the MCFA is essential for understanding the overall vascular network. Even in cases of distal pathology, tracking the MCFA helps guide interventions and predict ischemic areas3. Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the interruption of blood flow, including increased intraosseous pressure, fat embolism, and endothelial damage. These factors can disrupt circulation, contributing to the onset of osteonecrosis4. Additionally, genetic and mechanical factors influence ONFH development, underscoring its complex pathophysiology5,6.

Early detection of ONFH is crucial for effective treatment, yet traditional imaging methods like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), X-rays, and CT scans face significant challenges in capturing the earliest stages of the disease. While MRI is the most sensitive option for detecting signs such as marrow edema before structural bone damage appears, it still falls short in identifying initial vascular changes that precede necrosis7. X-rays and CT scans are generally ineffective in early stages as they only detect advanced bone changes and carry the added drawback of radiation exposure, which limits their repetitive use for monitoring disease progression or treatment response8.

Color Doppler Ultrasound serves as a significant diagnostic tool in the assessment of ONFH by providing real-time images of blood perfusion. Unlike MRI and CT scans, ultrasound offers the advantage of evaluating dynamic blood flow, particularly in the medial circumflex femoral artery, crucial for maintaining the viability of the femoral head9. The primary advantage of using Color Doppler Ultrasound in orthopedic conditions lies in its ability to detect alterations in blood flow characteristics early in the disease process. This ability makes it invaluable for early diagnosis and for monitoring the efficacy of interventions aimed at improving vascular supply to the affected area. Additionally, ultrasound is non-invasive, does not involve ionizing radiation, and can be used repetitively for follow-up, providing a safe and effective method for longitudinal patient management10.

Research on ONFH has traditionally emphasized structural changes detectable by MRI, often neglecting the early vascular alterations crucial for timely diagnosis. A notable gap persists in understanding the early blood flow characteristics essential for intervention11, which this study aims to address through detailed ultrasound analysis of the medial circumflex femoral artery, a significantly underexplored area despite its potential to enhance early diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes. The objectives include evaluating blood flow parameters in ONFH patients to understand vascular changes across different disease stages, comparing these parameters to delineate their relationship with disease progression, and assessing the potential of ultrasound as an indicator of disease severity, which could substantially improve early diagnosis and treatment strategies. The anticipated findings could transform clinical practices by incorporating advanced ultrasound techniques into the ONFH diagnostic protocol. Identifying early vascular changes will enable clinicians to initiate preventive treatments that could reduce the need for invasive surgeries, such as joint replacements, thereby enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life.

Research methods

Study subjects

This study was a single-center, prospective, parallel-controlled clinical trial. It involved 30 patients with necrosis of the femoral head and 30 healthy adult volunteers, all of whom visited the Department of Orthopedics at Wangjing Hospital of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences between April 2021 and January 2022. Color Doppler Ultrasound examinations were conducted by professional staff from our hospital’s ultrasound department, following the same parameter standards for both patients and healthy adults. The data were collected and preserved by the ultrasound professionals. Concurrently, hip joint X-rays, CT scans, and MRI, with all data being saved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wangjing Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Approval Number: WJEC-KT-2021-024-P002). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnostic criteria used in this study were based on the internationally recognized Mont12 standards:

Specific Criteria: Femoral head collapse; linear radiolucent shadows on X-rays beneath the cartilage layer; necrosis on the anterior-lateral side of the femoral head; ECT showing a radiation-increased zone surrounding a radiation-decreased area; MRI T2-weighted double line sign; bone biopsy showing empty lacunae.

Non-specific Criteria: Femoral head collapse with joint space narrowing; mixed cystic changes and sclerosis within the femoral head; increased activity on bone scan; MRI showing bone marrow edema; pain during hip joint movement with normal X-ray images; history of alcohol consumption or steroid use; bone biopsy showing bone marrow edema or fibrosis.

A diagnosis is established if criteria from either category are met concurrently.

Staging criteria

Referencing the 2019 necrosis staging criteria from the Association for Research on Circulation Osseous (ARCO)9.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Meets the aforementioned diagnostic criteria;

-

2.

Aged 18–55 years;

-

3.

Patient has signed an informed consent form agreeing to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients who do not meet the inclusion criteria;

-

2.

Traumatic etiology of femoral head necrosis

-

3.

Individuals with current or past hip joint infections;

-

4.

Pregnant or lactating women;

-

5.

Patients with severe primary diseases of the cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, liver, kidney, and hematopoietic systems, especially those with coagulation disorders.

Equipment and examination methods

Equipment: Philips IU 22 Color Doppler Ultrasound diagnostic system is used. Linear array probes: L9-3, L12-5 (the latter has a higher frequency and is suitable for slimmer individuals).

Examination Method: The examinee is positioned supine with the limb to be examined slightly abducted and externally rotated, toes pointing upwards. Using the 9L linear array probe, the examination involves scanning along the course of the femoral artery from the midpoint of the inguinal fold downwards, successively examining the femoral artery, deep femoral artery, and superficial femoral artery. The probe is placed transversely just below the inguinal ligament, slightly angled upwards, displaying the medial circumflex femoral artery with its transverse and ascending branches. The transverse branch runs between the adductor longus and adductor brevis muscles, while the ascending branch travels upward between the obturator externus and adductor brevis muscles. The deep branch proceeds deeply through the space between the pectineus, adductor longus, and iliopsoas muscles. Doppler ultrasound sample volume is placed at the center of the lumen of the medial circumflex femoral artery, at an angle less than 60° to the direction of blood flow, clearly displaying arterial blood flow for 3–4 cardiac cycles. The internal diameter (D) of the medial circumflex femoral artery is measured manually, and blood flow parameters such as peak systolic velocity (PSV), resistance index (RI), and pulsatility index (PI) are measured automatically by the computer system. Measurements are taken three times consecutively, and the average value is recorded.

All color Doppler ultrasound examinations were performed by a trained and experienced professional specializing in vascular ultrasound. A single, qualified observer conducted all ultrasound procedures, ensuring consistency and accuracy in evaluating blood flow parameters.

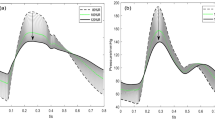

To provide a visual understanding of the ultrasound evaluation process, we have included a schematic diagram of the ultrasonic display interface used in this study (Fig. 1). This diagram shows the ultrasound record of a patient, highlighting the real-time blood flow velocity waveforms and the measured parameters, including PSV, RI, and PI, which are critical for our analysis.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 19.0. Data for each group are presented as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s). Normality tests were conducted on the data; groups conforming to a normal distribution were compared using one-way ANOVA. For homogeneous variances, the LSD method was applied, and for heterogeneous variances, Tamhane’s T2 or Dunnett’s T3 methods were used. For data not conforming to a normal distribution, the rank sum test for multiple independent samples was used. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of vascular and blood flow changes in the medial circumflex femoral artery in patients with ONFH

The study included 30 patients with ONFH (52 hips) and 30 healthy controls (57 hips). Color Doppler Ultrasound examinations of the medial circumflex femoral artery were conducted according to clinical ultrasound standards, collecting data on D and blood flow parameters (PSV, RI and PI), and analyzing the characteristics of vascular and blood flow changes in the medial circumflex femoral artery in ONFH.

The results showed:

Diameter of the artery in the necrosis group was 0.22 ± 0.03, compared to 0.22 ± 0.04 in the healthy group, with no significant difference (p = 0.604).

Peak systolic velocity in the necrosis group was 54.89 ± 26.30, significantly different from 75.31 ± 27.69 in the healthy group (p < 0.001).

Resistance index in the necrosis group was 0.88 ± 0.05, significantly different from 0.92 ± 0.06 in the healthy group (p = 0.003).

Pulsatility index in the necrosis group was 2.80 ± 0.86, compared to 3.22 ± 1.32 in the healthy group, with no significant difference (p = 0.051) (results shown in Table 1).

Blood flow parameters across different stages of femoral head necrosis

According to the 2019 staging criteria for femoral head necrosis by the ARCO, 30 patients with ONFH (52 hips) were included. Under standard clinical ultrasonography protocols, Color Doppler Ultrasound examinations were conducted on the medial circumflex femoral artery to collect data on D and blood flow parameters (PSV, RI and PI). The study analyzed differences in blood flow parameters across different stages of femoral head necrosis. The findings are as follows:

Included were: Stage ARCO I (2 hips), Stage II (24 hips), Stage III (24 hips), Stage IV (2 hips).

Significant differences in arterial diameter were observed among the stages. Comparatively, Stage I had a diameter of 0.26 ± 0.03 cm, Stage II was 0.22 ± 0.03 cm, Stage III was 0.21 ± 0.03 cm, and Stage IV was 0.20 ± 0.05 cm (p < 0.05). No significant differences were noted between Stages II, III, and IV.

Peak systolic velocities also differed significantly, with Stage I velocity at 103.50 ± 2.12 cm/s, Stage II at 59.13 ± 16.36 cm/s, Stage III at 42.85 ± 9.57 cm/s, and Stage IV at 28.35 ± 0.21 cm/s (p < 0.001).

Resistance indices showed significant differences, with Stage I at 0.97 ± 0.01, Stage II at 0.90 ± 0.04, Stage III at 0.87 ± 0.04, and Stage IV at 0.76 ± 0.02 (p < 0.001).

Pulsatility indices varied greatly among stages, with Stage I at 4.93 ± 0.33, decreasing to 2.96 ± 0.65 in Stage II, 2.57 ± 0.75 in Stage III, and 1.46 ± 0.08 in Stage IV (p < 0.001). No significant statistical difference was noted between Stages II and III. (Results shown in Table 2).

Differences in blood flow parameters before and after collapse of femoral head necrosis

Following the ARCO 2019 necrosis staging criteria, 30 patients with ONFH (52 hips) were examined. Color Doppler Ultrasound of the medial circumflex femoral artery was performed according to clinical ultrasonography standards to collect data on D and blood flow parameters (PSV, RI and PI). This section analyzes differences in these parameters before and after the collapse of the necrotic femoral head. Research results revealed:

Included were 26 hips in the non-collapse group and 26 hips in the collapse group.

There was no significant difference in arterial diameter between the non-collapse (0.22 ± 0.03 cm) and collapse groups (0.21 ± 0.03 cm, p = 0.054).

Significant differences were observed in peak systolic velocities; the non-collapse group had a velocity of 62.54 ± 19.80 cm/s, while the collapse group showed 47.24 ± 29.95 cm/s (p = 0.035).

The resistance indices also differed significantly; the non-collapse group recorded 0.90 ± 0.05 and the collapse group 0.87 ± 0.05 (p = 0.017).

Significant differences were found in pulsatility indices, with the non-collapse group at 3.11 ± 0.82 and the collapse group at 2.48 ± 0.78 (p = 0.008) (Results shown in Table 3).

Discussion

Interpretation of findings

Overview of vascular changes across disease stages

Arterial diameter in the early stages of ONFH shows consistency between necrotic and healthy groups (Table 1), suggesting that the basic vascular structure remains mostly intact. These findings align with gadobutrol-based steady-state MR angiography results, confirming that major vascular pathways do not undergo immediate structural changes at the onset of osteonecrosis13. This stability underscores a compensatory response to maintain adequate blood flow, which is crucial for diagnostic practices. As the disease progresses, the progression of femoral head necrosis from Stage ARCO I to IV is marked by a decrease in arterial diameter, although the differences between Stages II to IV are not significant (Tables 2 and 3), reflecting gradual atrophy of vessels due to local circulatory disturbances. Additionally, observations suggest that there is no significant change in vessel diameter in the collapsed group, highlighting that structural changes in arteries may not be pivotal in the progression of necrosis.

PSV shows a reduction across all stages of ONFH, consistently indicating a decrease in blood flow speed. This decrease signals early vascular compromise that worsens as the disease progresses. In the collapsed group, a significant drop in PSV points to a compromised blood supply post-collapse, serving as an early marker for detecting and monitoring disease progression.

RI is initially lower in necrotic groups (Table 1), suggesting compensatory mechanisms like vasodilation or the development of collateral vessels to maintain adequate perfusion. This observation aligns with insights from Lubas , who discuss variations in renal RI as possible early signs of vascular adaptation in cardiovascular conditions14. As the disease progresses (Table 2), the continued decrease in RI indicates a progressive loss of vascular autoregulation and an increase in compensatory collateral circulation, which paradoxically lowers the resistance index as disease severity increases. This presents a surprising contradiction to the common assumption that an increased RI, indicating restricted blood supply, would likely accelerate femoral head necrosis. Instead, our observations suggest a pathological adaptation where vessels lose their ability to constrict in response to reduced blood flow, failing to maintain adequate perfusion pressure. Crutchley et al. , in their study on atherosclerotic renovascular disease, highlight how RI can serve as a nuanced marker reflecting both disease progression and compensatory mechanisms in the renal system. This analogy supports our observations that a similar complex interplay between disease progression and vascular adaptation occurs in femoral head necrosis15. In collapsed states, further decreases in RI signal extensive vascular compromise (Table 3), reflecting a significant loss of vascular control mechanisms as femoral head necrosis advances. This reduction may indicate compensatory mechanisms attempting to enhance blood flow to ischemic areas, though often insufficiently. This counterintuitive finding underscores the complexity of vascular changes and challenges common perceptions.

PI remains stable in the early stages (Table 1), suggesting that pulsatility remains stable initially, which might not serve as the earliest indicator of vascular impairment. However, the significant decrease in PI across later stages (Table 2) and in collapsed conditions (Table 3) reflects worsening vascular elasticity and increased peripheral resistance, emphasizing the deteriorating condition of the vascular system, which complicates effective blood perfusion to the affected area.

Integrating multiple blood flow parameters for enhanced understanding of ONFH progression

When considering the collective changes in RI, PSV, PI, alongside stable arterial diameters, a complex and multifaceted picture of disease progression in ONFH emerges. As both PSV and PI decrease across the stages of the disease, they indicate a reduction in blood flow velocity and pulsatility, typical signs of advancing disease. This reduction, coupled with a decreasing RI, suggests an overall vascular deterioration where not only is the blood flow reduced, but the dynamic response of the vessels to blood flow is also impaired.

The constancy of arterial diameter across different stages and groups underscores that the primary changes are functional rather than structural. This stability, despite functional declines, suggests that the decrease in RI primarily results from changes at the microvascular level or in vascular tone and compliance, rather than alterations in arterial size. These changes could be linked to endothelial function, which regulates vascular tone. Recent studies using advanced ultrasound imaging technology reinforce this perspective. Yan et al. demonstrated through contrast-enhanced ultrasound that microcirculatory perfusion in adults with early osteonecrosis of the femoral head exhibits faster vascular clearance, indicating dynamic microvascular changes despite stable arterial sizes16. Furthermore, Zhang et al. identified that vascular and microvascular endothelial changes are central to the pathogenesis and progression of steroid-induced osteonecrosis, suggesting that microvascular dysfunction is a critical factor even when macroscopic arterial dimensions remain unchanged17. Moreover, the advancements in vascular ultrasound imaging reviewed by Golemati and Cokkinos have shown the capability of these technologies to detect subtle changes in the microvasculature, which can be pivotal for understanding the functional declines observed in osteonecrosis without apparent changes in arterial size18.

Furthermore, the relationship between RI and PSV in ONFH is particularly revealing. Typically, one would expect that a decrease in RI, indicating lower vascular resistance, would correspond with an increase in PSV. However, in ONFH, both RI and PSV decrease, suggesting that despite a lowering of vascular resistance, there is a significant reduction in effective blood flow, likely due to damage to the vascular beds in advanced disease stages. This atypical relationship points to significant vascular compromise that might not be immediately apparent through traditional diagnostic parameters alone. The simultaneous decrease in RI and PI also provides critical insights. While RI measures overall resistance in the vessel, PI provides insight into the blood flow’s pulsatility within the vessel. A decrease in both indices across disease stages suggests a progression towards a more passive vascular system, where the vessels are less capable of responding to physiological demands for increased blood flow. This may indicate compromised vessel elasticity and function, which are crucial during stages of active disease management.

Studies such as the one conducted by Ghasemi et al. , which utilized Doppler ultrasonography to evaluate arterial blood supply in the hip joints of skeletally immature cats, underscore the utility of RI and PSV as diagnostic markers. While focused on animal models, their findings affirm the diagnostic potential of these indices in assessing vascular integrity under varying health conditions, providing a foundation for their application in human ONFH19. Conversely, Mehta et al. found that in cases of septic arthritis, an inflammatory condition, PSV increased significantly in inflamed hips, contrasting with the simultaneous decrease of both indices observed in ONFH. This divergence suggests a distinct mechanism of vascular impairment in ONFH compared to purely inflammatory conditions20. Furthermore, the research by Adekile et al. , which also highlighted the critical role of RI and PSV in monitoring microvascular health, suggests that these indices are pivotal in detecting subtle vascular dysfunctions that might parallel those in ONFH21.

Clinical Implications of ultrasound parameters in ONFH

Diagnostic enhancement

Early Detection: The subtlety of early vascular changes can be crucial in diagnosing ONFH before significant anatomical damage occurs. Observing early decreases in RI and PSV, particularly when D remains unchanged, might indicate the onset of vascular insufficiency. This could allow for interventions that are less invasive and more effective in preserving the femoral head before structural damage sets in. Routine screening using these parameters could become part of a standardized approach for high-risk populations, such as steroid users or those with a history of significant alcohol intake. Supporting this, research by Yan et al. (2023) highlights the effectiveness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in detecting early subchondral bone microcirculatory perfusion in ONFH patients, affirming the diagnostic value of early ultrasound parameter changes16.

Differentiating Disease Stages: By quantifying the changes in RI, PSV, and PI across the different stages of ONFH, clinicians can define the severity of the disease more precisely. This distinction is critical not just for clinical documentation and communication but also for aligning treatment strategies with the specific needs at each disease stage. For example, a lower RI coupled with a significantly reduced PSV and PI might indicate an advanced stage, which is critical for planning the intensity and nature of the treatment.

Prognostic applications

Predicting Disease Progression: Longitudinal monitoring of ultrasound parameters can serve as a trend analysis tool, predicting the trajectory of the disease. For example, a progressive decline in RI and PSV may precede visible signs of collapse, serving as a warning to intensify or alter therapeutic strategies. This kind of predictive monitoring could be integral in managing ONFH proactively, possibly extending the joint’s viability and delaying or avoiding surgical interventions.

Assessing Treatment Efficacy: After initiating treatment, whether pharmacologic or physical, changes in these ultrasound parameters can provide objective evidence of improvement or stabilization. An improvement in PSV and stabilization of RI after a vasodilator treatment, for instance, could objectively demonstrate restoration of blood flow, validating the therapeutic approach and guiding further treatment durations and intensities.

Informing treatment decisions

Tailoring Therapeutic Approaches: Different therapeutic strategies can be optimized based on specific ultrasound findings. If vascular parameters continue to worsen despite stable arterial diameter, it might suggest that the disease’s impact is primarily at a microvascular or functional level rather than a gross anatomical one. This could suggest that interventions focusing solely on structural support (like core decompression) might be less effective, and that vascular-targeted therapies (like vasodilators or anti-coagulants) could be more beneficial.

Guiding Surgical Timing: When ultrasound parameters such as RI and PSV show rapid deterioration, it indicates that conservative treatments may no longer be effective. This early recognition of vascular compromise allows for preemptive surgical planning. For example, opting for core decompression before the joint collapses can preserve more of the natural joint structure, enhancing surgical outcomes and recovery. Thus, monitoring these parameters closely guides clinicians in making timely, critical decisions about escalating to surgical interventions.

Enhancing patient monitoring

Longitudinal Management: Implementing a routine ultrasound parameter monitoring protocol can help in dynamically managing ONFH. This could allow for a personalized, adaptive management strategy where treatment intensities are adjusted based on real-time feedback from ultrasound assessments. Such an approach could improve patient adherence to treatment protocols, reassure patients through visible improvements or stability in their condition, and reduce the overall burden of the disease through optimized management.

By incorporating these ultrasound parameters into routine diagnostic and monitoring protocols, clinicians can not only enhance the accuracy of their assessments but also adopt a more proactive approach in managing ONFH. This would fundamentally shift the focus from reactive to preventive care, optimizing outcomes by maintaining joint functionality and reducing the need for high-risk surgical interventions.

Limitations of the study

The study’s primary limitation is its small sample size, which could impact the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. This size constraint may not capture the full variability or subtle vascular changes associated with ONFH. Additionally, the observational nature of the study limits our ability to draw conclusions about causality or the directionality of changes in vascular parameters. Without a longitudinal framework, it’s challenging to determine how these parameters evolve over the course of the disease. The study’s reliance solely on ultrasound imaging also poses a limitation, as incorporating other diagnostic modalities like MRI or biochemical markers could provide a more comprehensive understanding of ONFH.

Future research directions

Future research should incorporate longitudinal studies to track the progression of vascular changes in ONFH over time, which would help in understanding how early changes correlate with long-term outcomes. Enlarging the study sample and ensuring diversity within it would strengthen the reliability of the findings and aid in exploring the effects of different therapies on varied demographic groups. Furthermore, intervention studies are crucial to determine the efficacy of various treatments on altering vascular parameters and their ability to modify disease progression. Employing a multi-modal diagnostic approach that combines ultrasound with MRI, CT scans, and biochemical markers could yield a richer, more detailed picture of ONFH. Lastly, investigating the molecular and biochemical pathways that influence vascular alterations could unveil new therapeutic targets, offering potential for early interventions before significant bone damage ensues. These directions not only promise to deepen our understanding of ONFH but also aim to improve diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes for patients suffering from this debilitating condition.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that blood flow alterations in the medial circumflex femoral artery are significant indicators of ONFH. Our findings reveal that while arterial diameter remains largely unchanged, there are significant decreases in PSV and RI, which are evident across different stages of the disease. These parameters offer critical insights into the vascular dynamics underlying ONFH, suggesting that they could serve as valuable clinical indicators for early diagnosis, disease progression monitoring, and treatment efficacy assessment.

The use of Color Doppler Ultrasound in evaluating these blood flow parameters provides a non-invasive, real-time diagnostic tool that can detect early vascular changes before structural damage occurs. This capability underscores the importance of incorporating ultrasound-based assessments into routine clinical practice for patients at risk of ONFH, particularly those with high-dose corticosteroid use or significant alcohol consumption.

In summary, our study highlights the relevance of vascular assessments in understanding and managing ONFH, paving the way for improved diagnostic protocols and therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving femoral head viability and enhancing patient outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cohen-Rosenblum, A. & Cui, Q. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 50, 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2018.10.001 (2019).

Petek, D., Hannouche, D. & Suva, D. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: pathophysiology and current concepts of treatment. EFORT Open Rev. 4, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1302/2058-5241.4.180036 (2019).

Zlotorowicz, M., Szczodry, M., Czubak, J. & Ciszek, B. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery with respect to the vascularity of the femoral head. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 93, 1471–1474. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.93B11.26993 (2011).

Lee, Y. J., Cui, Q. & Koo, K.-H. Is there a role of pharmacological treatments in the prevention or treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head?: A systematic review. J. Bone Metab. 26, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.11005/jbm.2019.26.1.13 (2019).

Wang, P. et al. The role of structural deterioration and biomechanical changes of the necrotic lesion in collapse mechanism of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Orthop. Surg. 14, 831–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.13277 (2022).

Migliorini, F. et al. Prognostic factors in the management of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A systematic review. Surgeon 21, 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2021.12.004 (2023).

Zhang, Y.-Z. et al. Accuracy of MRI diagnosis of early osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 13, 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0836-8 (2018).

Cardín-Pereda, A. et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A multidisciplinary approach in diagnostic accuracy. Diagnostics 12, 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12071731 (2022).

Zhao, D. et al. Guidelines for clinical diagnosis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in adults (2019 version). J. Orthopaedic Transl. 21, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2019.12.004 (2020).

Fu, W., Liu, B., Wang, B. & Zhao, D. Early diagnosis and treatment of steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Int. Orthop. (SICOT) 43, 1083–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4011-y (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. Methods to predict osteonecrosis of femoral head after femoral neck fracture: a systematic review of the literature. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18, 377. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03858-7 (2023).

Marker, D. R. et al. Treatment of early stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head. JBJS 90, 175. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00671 (2008).

Liao, Z. et al. Evaluating blood supply changes in the osteonecrosis of the femoral head using gadobutrol-based steady-state MR angiography. Eur. Radiol. 33, 8597–8604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-09899-0 (2023).

Lubas, A., Kade, G. & Niemczyk, S. Renal resistive index as a marker of vascular damage in cardiovascular diseases. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 46, 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-013-0528-6 (2014).

Crutchley, T. A. et al. Clinical utility of the resistive index in atherosclerotic renovascular disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 49, 148-155.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.008 (2009).

Yan, M., Li, R., Hu, D. & Zhao, P. Detection of subchondral bone microcirculatory perfusion in adults with early osteonecrosis of the femoral head using contrast-enhanced ultrasound: A prospective study. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 49, 635–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2022.10.004 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. FAR591 promotes the pathogenesis and progression of SONFH by regulating Fos expression to mediate the apoptosis of bone microvascular endothelial cells. Bone Res. 11, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-023-00259-8 (2023).

Golemati, S. & Cokkinos, D. D. Recent advances in vascular ultrasound imaging technology and their clinical implications. Ultrasonics 119, 106599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2021.106599 (2022).

Ghasemi, E., Molazem, M., Soroori, S., Masoudifard, M. & Pedram, M. S. Doppler ultrasonography can be used to evaluate the arterial blood supply of hip joints in skeletally immature cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 84, ajvr.23.07.0162. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.23.07.0162 (2023).

Mehta, R., Agrawal, A., Aroojis, A., Lavande, A. & Karnik, A. Perfusion changes in acute septic arthritis of the hip joint during infancy using doppler USG. JOIO 58, 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43465-023-01044-9 (2024).

Asbeutah, A. M., Zahra, A. M., Al-Abboh, H., AlMajran, A. A. & Adekile, A. Repeat transcranial Doppler ultrasound imaging in Kuwaiti children with sickle cell disease after a 10-year interval: A prospective, cohort study. Health Sci. Rep. 6, e1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1159 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants and staff at Wangjing Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, for their support and contributions to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation [Grant Numbers 7222298].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J. YANG conceived the study, conducted the research, and wrote the manuscript. Y. LI and P.P. WEN contributed to data collection. Z.X. WU and X. YE were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. C. ZHANG, S.Y. SUN, G.Y. ZHANG, Y.F. SUN, and C.K. ZHOU contributed to the interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. R. YE provided significant support in the study design and coordination. H.J. HE supervised the study, provided overall guidance, and is the corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wangjing Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Approval Number: WJEC-KT-2021–024-P002). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Tj., Li, Y., Wen, Pp. et al. Clinical evaluation of blood flow in femoral head necrosis using color doppler ultrasound. Sci Rep 15, 13260 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98198-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98198-3