Abstract

During a specific task, the whole-body motion favors those with muscles suited for its execution; in addition, it leads to adaptations in muscle morphology and function of muscles. Thus, the well suited and/or adapted muscles are particularly crucial for enhancing performance in each competitive sport. Here, we compared muscle morphology, strength, and EMG activity during isometric maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) at multiple hip angles in runners and cyclists with similar sagittal motion (but different ranges of motion) during competition. Ten sprint track runners and ten sprint track cyclists performed the MVC test of hip extension, and magnetic resonance images of the buttocks and thighs were acquired. Maximum hip extension torque and surface electromyography (EMG) signals from the gluteus maximus (GM) biceps femoris long head (BFlh) and semitendinosus (ST) muscles were assessed during the MVC test at six hip flexion angles (45°, 60°, 75°, 90°, 105°, and 120°). Muscle volumes were determined using magnetic resonance images. Cyclists had a significantly higher MVC torque normalized by the muscle volume than that observed in runners at a hip flexion angle of 120°. At hip flexion angles of 105° and 120°, the normalized root mean square of the EMG signal in cyclists was significantly higher than in runners. Torque-angle relationship in hip extension differed between runners and cyclists, with cyclists generating greater extension torque by increasing GM muscle EMG activity in the flexed position. This may differ in the neuromuscular adaptation to and/or suitability for specific tasks of hip extensor morphology and function in runners and cyclists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Activation of skeletal muscles initiates movement in related body segments, ultimately generating whole-body motion. During a specific task, the whole-body motion favors those with muscles suited for its execution; in addition, it leads to adaptations in muscle morphology and function of muscles1,2,3,4,5. Thus, the well suited and/or adapted muscles are particularly crucial for enhancing performance in each competitive sport.

In sports science, task-specific muscle morphology and function can be elucidated through comparisons of muscular characteristics among different types of athletes3,6,7. In the body, relatively large muscles close to the center of mass (COM) function as force generators and influence sports performance8,9,10,11. In particular, the muscles around the hip joint that extend the leg backward play a crucial role in numerous whole-body motions. Therefore, various studies have been conducted to investigate their hip extensor morphology8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Regardless of the movement patterns, both hip and knee extensor muscles have been shown to be associated with faster forward movement performance such as running11,18 and cycling16. While previous studies have investigated the moment-angle relationship in knee extension3,7, no research has clarified this relationship in hip extension.

For sprint runners, who specialize 100-m, 200-m, and 400-m events, an important task is to achieve a high maximum running speed by pushing off the ground and maintaining it until the finish line20,21. Running speed is primarily generated by an exercise in which the lower limb is repeatedly extended and flexed in the sagittal plane at a high rate22. Repeated competition-specific exercises and daily training lead to adaptation to specific muscle profiles associated with a task15. Therefore, runners have significantly greater hip and thigh muscle mass compared to that in the general population, adapted to and/or suited for running motion11,13,17,19. Hip extension plays a vital role in achieving high running speed. Previous studies have reported significant development in the gluteus maximus (GM) muscle, responsible for hip extension, and the posterior thigh muscles11,13,17,19.

Similar to running, cycling is an exercise involving repeated extension and flexion of the lower limbs in the sagittal plane. During cycling, the crank power required to move the COM is generated by the hip and knee extension torques23. Therefore, cyclists as well as runners have been reported to have morphologically larger GM and thigh musculature than those in the general population24. However, in these sports, the same lower limb extensor strength may be applied in varying postures. For instance, the hip flexion angle at which the maximum hip extension torque is observed is approximately 100° for cyclists25 and 40° for runners26, indicating that cyclists adopt a more flexed position. A recent previous study reported that protocols involving muscle contraction from a state of greater stretch resulted in significantly greater muscle hypertrophy than those starting from a position of less stretch27. Based on these findings, the morphological characteristics of muscles may differ between running and cycling even though their modes of locomotion are similar. However, the morphological characteristics of the muscles of the two athletes (runners and cyclists) with similar movement tasks have not yet been examined.

The magnitude of muscular force depends on the force-length relationship28, which is affected by the joint angle. Classically, muscle fiber length and structure are similar between individuals29. However, several previous studies have reported slight variations in the force-length relationship of muscles3,30. Herzog et al. discovered that the rectus femoris muscle exhibits different characteristics in its force-length relationship between runners and cyclists3, suggesting adaptations to their chronically imposed functional tasks. Adaptation of muscle force-length relationships to the task would also be expected in the hip extensor muscle groups that generate propulsive forces during both running and cycling. Specifically, cyclists have been reported to have a maximum hip flexion angle of 122°, indicative of a pronounced degree of flexion31. Hip flexion causes stretching of the GM and posterior thigh muscles; thus, the hip flexor muscles may be used in a relatively more stretched position in cyclists than in runners.

This study aimed to determine the task-specific strategies of athletes in two sagittal plane tasks (running and cycling) performed at different joint angle ranges. The specific purpose was to determine the differences in the volumes of hip extensor muscles and their activations at various joint angles during the strength test between runners and cyclists. We hypothesized that (1) cyclists who chronically produce the maximum extension torque in a more flexed position would have larger hip extensor muscle volumes than those in runners, and (2) compared to runners, cyclists would have greater hip extension torque and higher hip extensor muscle activations in a more flexed position.

Results

Body characteristics

Body masses of runners and cyclists were 63.6 ± 4.4 kg and 71.6 ± 3.5 kg, respectively (Table 1), and a significant difference was observed between them (Z = 2.857, P < 0.002). Other characteristics, including height, thigh length, and muscle length of the SM, ST, BFlh, BFsh, and GM were not significantly different between the groups (Table 1).

Muscle volume

The medians (and quantiles) of the absolute and normalized muscle volumes are presented in Table 2. The absolute and normalized muscle volumes of the ST in runners were significantly higher than those in cyclists (absolute: Z = − 2.561, P = 0.005; normalized: Z = − 3.152, P = 0.001). In contrast, the absolute and normalized muscle volumes of the SM, BFlh, BFsh, and GM were not significantly different between the two groups.

Hip extension torque during MVC test

Absolute hip extension torque is demonstrated in Fig. 1. A Friedman test demonstrated a significant main effect of the group in absolute hip extension torque (χ2 = 9.504, P = 0.002); significant differences were observed between the two groups in 90° and 120° conditions (90°: Z = 1.773, P = 0.038; 120°: Z = 1.839, P = 0.033). The Friedman test also yielded significant effects, highlighting the angle condition as the primary factor (χ2 = 61.305, P < 0.002). Both groups demonstrated significantly higher values for the conditions at 60° and above than those observed for conditions at 45° (all conditions Z = − 2.889, P < 0.001 in runners and cyclists). Cyclists displayed significantly higher values for the above 75° conditions than for 60° condition (at 75°: Z = − 2.712; 90°: Z = − 2.712; 105°: Z = − 2.801; 120°: Z = − 2.801, all conditions P < 0.003), with 120° condition displaying higher values than the 75° condition (Z = − 2.801, P = 0.003). In runners, the absolute hip extension torque was higher in the 105° condition than that in the 60° condition (Z = − 2.889, P = 0.002).

Absolute hip extension torque performed on maximal voluntary contraction test with six hip flexion angle conditions. aP < 0.01 indicates a significant difference from 45° condition; bP < 0.01 indicates a significant difference from 60° condition; cP < 0.01 indicates a significant difference from 75° condition; †P < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between groups.

For the normalized hip extension torques (Fig. 2), a significant main effect of hip extension angle condition on the hip torque normalized by muscle volume was observed in cyclists (χ2 = 12.332, P < 0.001). No significant main effects were observed for either variable in the runners. The Mann–Whitney U test demonstrated that the hip extension torque normalized by the muscle volume of cyclists was significantly higher than that of runners in the 120° condition (Z = 2.495, P = 0.006). There was not a significant main effect of hip extension angle condition on the hip torque normalized by body mass.

RMS of EMG signals during MVC test

A Friedman test revealed a significant main effect of group in normalized muscle EMG activity of GM (χ2 = 6.603, P = 0.010); significant differences were noted between the two groups in the 105° and 120° condition (105°: Z = 1.904, P = 0.028; 120°: Z = 1.773, P = 0.038; Fig. 3).

Normalized root mean squire (RMS) of electromyography (EMG) signals in biceps femoris long head (BFlh, panel a), semitendinosus (ST, panel b), and gluteus maximus (GM, panel c) muscles during the isometric maximal voluntary contraction test performed under six hip flexion angle conditions. †P < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between groups.

Discussion

This study examined the hypothesis that differences in specific hip-extensor muscle morphology and function between runners and cyclists, who move forward as a daily specialized tasks under different sagittal plane joint angle ranges. Our findings were as follows: the ST muscle volume of runners was significantly larger than that of cyclists. In contrast, no significant differences were identified between the two groups in terms of the muscle volumes of the other hip extensor muscles. Both the absolute and muscle volume-normalized values of the hip extension torque of cyclists were significantly higher than those of runners in the flexed position. At the same time, cyclists demonstrated a significantly higher RMS of the EMG signals of the GM muscle in the flexed position relative to runners. The results of this study suggest that runners and cyclists might adapt to specific tasks that require the exertion of a large hip extension torque while maintaining an optimal flexed position.

A previous study reported that repeated contractions from more stretched states produced greater muscle hypertrophy in the hamstrings during resistance training27. In this study, we hypothesized that cyclists would have a significantly greater hip extensor muscle volume than that observed in runners. This is because both groups engaged in specialized maximal-effort exercises for similar durations, with cyclists operating in a maximum hip flexion position of 122°31, which is higher than the 100° observed in runners26. However, no significant differences were observed in any of the muscles in this study, except for ST (Table 2). However, these results do not support our first hypothesis.

Ema et al. reported that the volumes of ST and BFsh muscles in cyclists were higher than those in non-athletes8. Moreover, several previous studies have reported that the hip extensor muscle volumes are significantly higher in runners than in non-athletes13,17,19. In particular, the GM, ST, and BFlh of elite runners have been shown to be significantly higher than those of sub-elite runners11. A recent longitudinal study reported a significant increase in ST muscle volume following 12 months of sprint training for elite runner15. In this study, runners had significantly larger absolute and normalized volumes of ST muscle than those in the cyclists (Table 2). Therefore, the muscle morphology, in particular, ST muscle volume in runners might exhibit competition-specific adaptations compared to that in cyclists.

A previous study reported hip extensor muscle EMG activity with changes in running speed using high-density surface EMG32. Their results demonstrated significant muscle EMG activity beyond MVC in the BFlh and ST muscles during the stance and swing phases of high-speed sprinting, indicating that muscle activity occurred at an intensity that could not be assessed during general strength training33. The fusiform architecture of the ST muscle is designed to enable rapid muscle action34. Runners are required to perform a hip extension-flexion motion at high speeds considering that the step frequency can reach a maximum of about 4.12 Hz during a 400-m event21. In contrast, in cyclists, the frequency of motion in a 1000 m event is approximately 2.1 Hz35, which is less than that in runners. Additionally, during the latter half of swing phase in sprint running, the ST muscle performs eccentric contraction36, which greatly contributes to the muscle hypertrophy37. Thus, the specific hypertrophy of the ST muscle observed in runners might be the result of adaptation to specific high-frequency tasks and eccentric contraction.

In this study, the hip extension torque and muscle volume were measured in two types of athletes (400 m runners and 1 km time trial cyclists). At a hip flexion angle of 90° with a 90° knee flexion angle, a hip extension torque is reported to be 4.65 Nm/kg for the healthy young males38. The participants in this study had greater hip extension torque, which was approximately 9.65% for runners and 7.13 for cyclists higher than that reported by Tayashiki et al.38. This suggests that hip extensor muscles of runners and cyclists contribute to the greater hip extension torque than those of healthy young males. Hip extension movement plays an important role in the competitive performance of runners and cyclists and the acquisition of whole-body translational velocity. Therefore, the findings of this study suggest that the participants in this study were athletes who specifically adapted to and/or suited for hip extension exercises in the sagittal plane.

Based on findings that muscle hypertrophy adapts differently depending on the muscle stretch length during resistance training27 and that muscle force-length relationships adapt to and/or suit for specific tasks3,7, we postulated a second hypothesis that the torque-angle relationship of hip extension varies between runners and cyclists. The data on the torque-angle relationship in this study support our second hypothesis. Comparing the absolute values of hip extension torque, a trend of increasing torque was observed in cyclists with increasing flexion angles, whereas no change was observed in runners with flexion angles > 60° (Fig. 1). The cyclist produces maximum hip extension torque when the crank is at approximately 90° and the hip angle is approximately 100°25. In contrast, runners generate hip extension torque from the late swing phase to mid-stance with hip flexion angles ranging from 20–70°26,39. Therefore, cyclists may adapt to generate hip extension torque in a relatively more flexed hip position, whereas runners may adapt to generate hip extension torque in a relatively less flexed hip position, which is potentially reflected in the results of this study. This difference of angle-torque relationship according to athletic characteristics has been reported in several previous studies investigating knee extensors3,7, and our results demonstrated similar characteristics in the hip extensors of cyclists and runners.

Muscle strength is closely associated with the muscle size40. In the 120° hip flexion condition, the extension torque normalized by the absolute muscle volume was significantly higher in cyclists than in runners (Fig. 2). This result did not reflect the volume of the ST muscle, which was smaller in cyclists than in runners. The ST muscle is a fusiform muscle, which is advantageous for generating contraction force at the higher contraction velocities. Therefore, the larger ST muscle size of runners may reduce its contribution to generate the hip extension torque during an isometric strength test. On the other hand, during hip extension in the flexed position, compared with runners, cyclists exhibited significantly higher activation of the GM muscle (Fig. 3). These results suggest that cyclists increase muscle excitation, that is, motor unit recruitment and firing frequency, to generate significant extension torque at the flexed hip position. A similar finding has been reported that highly trained athletes can significantly increase the EMG amplitude of the rectus femoris muscles and improve knee extension strength41.

There are some limitations in this study. The first is that we measured EMG amplitude of hip extensor muscle according to the SENIAM method, in which the EMG electrode was attached at the midpoint of the muscles. This approach may have resulted in the absence of the innervation zone locations of the analyzed muscles. Some previous studies reported that with the innervation zone locations of the ST, BFlh, and GM clustered in the proximal region, with no innervation zone locations at intermediate positions42,43. In contrast, other reported that the location of the innervation zones is difficult to detect with high-density surface EMG in pinnate muscles such as the BFlh44. In addition, the muscle activity during the MVC differs in a region-specific manner33,45,46. Considering these factors, the EMG activity in this study must be interpreted carefully. The second limitation is that muscle strength was measured under isometric conditions, which differ from the dynamic hip flexion and extension movements involved in athletic activities such as running and cycling. Future studies should investigate the relationship between sport-specific muscle volume distribution and the force-velocity or torque-angular velocity characteristics of the hip extensors to better understand their functional relevance in dynamic performance. Third limitation is that moment arms of hip extensor muscles were not measured so as to evaluate the effect of muscle EMG activation on generating the extension moment. It has a direct effect on the moment production capacity of the muscles; however, that measurement may be challenging. This is because, unlike the knee and ankle joints, where tendons extend across the joints, the hip extensor muscles, such as the thick gluteus maximus, cross the hip joint, making it difficult to determine how to define the moment arm. A final limitation is that magnitudes of the external forces applied to feet varied between runners and cyclists. Runners are required to continuously support their body mass and to propel their center of mass against gravity with each step. The differing mechanisms of force generation by the lower-limb muscles, involving the hip extensors, in response to these external forces may influence muscle hypertrophy. Consequently, the biomechanical demands of running and cycling diverge, leading to distinct adaptations in the involved musculature.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the torque-angle relationship in hip extension differs between runners and cyclists, with cyclists generating greater extension torque by increasing GM muscle EMG activity in the flexed position. The observed differences in the torque-angle relationship of the muscle between runners and cyclists complement previous findings by Herzog et al.3 and Savelberg and Meijer7, which suggest that muscle EMG activity plays a role in shaping this relationship. In addition, ST muscle volume in runners was significantly larger than those in cyclists. This difference in ST muscle volume may be more relevant to dynamic conditions, such as eccentric and concentric contractions, rather than the isometric contractions measured in this study. Although this study does not directly associate the difference in ST muscle volume with distinct functional roles in hip extension, it suggests a potential influence on dynamic hip extension tasks. Thus, our results provide evidence of adaptation to and/or suitability for specific tasks of hip extensor morphology and function.

Methods

Participants

Eleven male track runners (major disciplines: 400 m dash, personal record: 49.46 ± 1.56 s, year of competitive experience: 7.1 ± 2.1 year) and eleven male track cyclists (major disciplines: 1000 m time trial, personal record: 66.784 ± 2.525 s, year of competitive experience: 5.0 ± 1.0 year) participated in this study (Table 1). All of them were of a level that would allow them to compete in national university games. Both groups had a specific competition duration of approximately 50–60 s for each event. Therefore, both groups can be considered athletes who utilize similar energy supply systems (mainly the yield of glycolysis) to perform their exercises. Additionally, runners can be characterized as a group that generates peak hip extension torque at less flexed hip angles, while cyclists can be characterized as a group that generates peak hip extension torque at more flexed hip angles. Following an explanation of the testing procedures, the participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. The experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Nippon Sport Science university (approval number: 021-H124) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental design

The participants visited the laboratory on three separate days. At the first visit, the participants performed the familiarization task of the isometric maximal voluntary contraction test (MVC test) for hip extension. The main MVC test was performed during the second visit. Magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of the buttocks and thighs were acquired during the third visit to the laboratory. The participants were instructed to refrain from performing any strenuous physical activity or drinking alcohol for 24 h before the study.

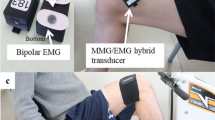

Measurements of MVC’s torque and root mean square (RMS) of electromyographic (EMG) signals

The MVC test was performed using an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex Multi-Joint System 4; Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY, USA). They performed the MVC test twice under each of the six hip flexion angle conditions (45°, 60°, 75°, 90°, 105°, and 120°). Participants were seated in a supine position with a parallel backrest and their right thighs were secured using an attachment connected to an input shaft equipped with a strain gage to measure torque. In this study, the hip flexion angle was defined as the angle formed by the pelvic vector connecting the superior posterior iliac spine to the superior anterior iliac spine and the femoral vector connecting the greater trochanter to the femoral condyle. The hip flexion angles could be monitored and accurately adjusted in the dynamometer, moving the shaft slowly. The thigh and shank were stabilized using an L-shaped metal frame to maintain a 90° knee joint angle throughout the test (Fig. 4a), ensuring that changes in the knee joint did not affect EMG activity47. In addition, to prevent changes in pelvic angle during the MVC test, participants were secured to the seat with a fabric belt (Fig. 4b). In all conditions, only the right leg was used, and the order of the six conditions was determined randomly. When the difference between the first and second measurements exceeded 5.0%, a third measurement was performed, and the trial with the average value across all trials was selected for analysis36. Prior to the MVC measurements, a practical and warm-up session consisting of a few submaximal isometric strength tests of hip extension at the three hip flexion positions of 45°, 90°, and 120° to familiarize the participants with the task required and allow for warm-up. To evaluate the EMG activity of the hip extensor muscles during MVC, surface EMG was recorded from the BFlh, ST, and GM muscles using surface EMG electrodes (DL-142; S&ME, Tokyo, Japan) at 1000 Hz. The electrode locations for the BFlh, ST, and GM were determined according to the recommendations of SENIAM48. The EMG signals were filtered using a fourth-order Butterworth filter (bandwidth was 20–400 Hz). The RMS was calculated in the selected 0.5 s of peak MVC torque (± 0.25 s) for evaluation of the strength of surface EMG signals in each channel. The RMS of the EMG signals in all conditions was normalized with respect to that in the 45° condition for comparison between the two groups. Hip extension torques were normalized by the body mass (hip extension torque normalized by body mass) and sum of absolute values of SM, ST, BFlh, BFsh, and GM muscle volumes (hip extension torque normalized by muscle volume).

Fixation method for knee joint and pelvis during the isometric maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) measurement. (a) The knee joint was fixed at 90° using a rectangular metal plate secured with nylon straps during the MVC measurement. (b) The pelvis was stabilized with an adjustable belt to minimize movement and ensure consistent positioning throughout the MVC measurement (90° hip flexion angle condition). The backrest was inclined at 20°.

Measurement of muscle volume and anatomical cross-sectional area (ACSA)

MRI scans for the right-side buttock and thigh (echo time: 2.3 ms, repetition time: 294.4 ms, field of view: 450 mm, slice thickness: 10 mm, interval: 10 mm, flip-angle: 80°, matrix: 320 × 192) were obtained using a 1.5-T MR scanner system (Echelon OVAL; Hitachi Medico Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The participants were positioned supine on the MRI table during the scan. A polyurethane cushioning material was placed over the back of the waist and lower legs to prevent deformation of the back of the thighs and a band brace was used to secure both the right and left legs to prevent external rotation. In addition, the cushioning material was placed over the lower ribs, pelvis, and patella to prevent pressure from the spinal coil positioned over the upper part of the body. The edges of the semimembranosus (SM), semitendinosus (ST), biceps femoris long head (BFlh), biceps femoris short head (BFsh), and GM muscles were manually outlined by the same researcher using the Osiris software (The University Hospital of Geneva, Switzerland). Care was taken to exclude visible adipose tissue and connective tissue incursions. Representative MRI scans for measuring the ACSAs of the buttock and thigh muscles are displayed in Fig. 5. The intra-investigator effect was validated by outlining the maximum circumferential circumference of each muscle twice, resulting in a coefficient of variation of 1.5 ± 1.8% and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.99. The volume of each muscle was determined by adding the ACSA to the slice thickness (10 mm). Thigh length was determined by measuring the length from the head of the greater trochanter to the articular cleft of the knee joint using sagittal MRI. To minimize the impact of body size on the differences in muscle size between runners and cyclists, normalized muscle volumes were calculated using absolute muscle volumes were divided by body height and mass.

An example of a magnetic resonance image of the right foot of a runner and a cyclist. (a) This image displays the maximum area of the gluteus maximus (GM) muscle obtained from the analysis. (b–d) These images display magnetic resonance images of each part of the thigh (b 70%, c 50%, d 30% of the distal thigh length). SM semimembranosus, ST semitendinosus, BFlh biceps femoris long head, BFsh biceps femoris short head.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were performed using MATLAB (version 9.8, Math Works, Natick, MA, USA). A Shapiro-Wilk test was performed on the data obtained in this study to examine normality. However, in the case of rejection, a Friedman test was performed. In the case of a significant Friedman test p-value (< 0.05), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess significant changes in the hip flexion angle conditions within the MVC torque and EMG. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare participant characteristics, MVC torque, EMG, and muscle morphology data. Statistical significance for multiple comparisons was adjusted using Bonferroni correction to avoid alpha-level inflation. All parameters are presented as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACSA:

-

Anatomical cross-sectional area

- BFlh:

-

Biceps femoris long head

- BFls:

-

Biceps femoris short head

- COM:

-

Center of mass

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- GM:

-

Gluteus maximus

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance image

- MVC:

-

Maximal voluntary contraction

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

- SM:

-

Semimembranosus

- ST:

-

Semitendinosus

References

Ema, R., Wakahara, T., Kanehisa, H. & Kawakami, Y. Inferior muscularity of the rectus femoris to vasti in varsity oarsmen. Int. J. Sports Med. 35, 293–297 (2014).

Harber, M. P. et al. Aerobic exercise training induces skeletal muscle hypertrophy and age-dependent adaptations in myofiber function in young and older men. J. Appl. Physiol. 113, 1495–1504 (2012).

Herzog, W., Guimaraes, A., Anton, M. & Carter-Erdman, K. Moment-length relations of rectus femoris muscles of speed skaters/cyclists and runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 23, 1289–1296 (1991).

Larsson, L., Grimby, G. & Karlsson, J. Muscle strength and speed of movement in relation to age and muscle morphology. J. Appl. Physiol. 46, 451–456 (1979).

Tracy, B. L. et al. Muscle quality. II. Effects of strength training in 65- to 75-yr-old men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. 86, 195–201 (1999).

Abe, T., Kumagai, K. & Brechue, W. F. Fascicle length of leg muscles is greater in sprinters than distance runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32, 1125–1129 (2000).

Savelberg, H. H. C. M. & Meijer, K. Contribution of mono- and biarticular muscles to extending knee joint moments in runners and cyclists. J. Appl. Physiol. 94, 2241–2248 (2003).

Ema, R., Wakahara, T., Yanaka, T., Kanehisa, H. & Kawakami, Y. Unique muscularity in cyclists’ thigh and trunk: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 26, 782–793 (2016).

Fujita, S. et al. A 100-m sprint time is associated with deep trunk muscle thickness in collegiate male sprinters. Front. Sports Act. Liv. 1, 32 (2019).

Hoshikawa, Y. et al. Influence of the Psoas major and thigh muscularity on 100-m times in junior sprinters. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 38, 2138–2143 (2006).

Miller, R. et al. The muscle morphology of elite sprint running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 53, 804–815 (2021).

Ema, R., Sakaguchi, M. & Kawakami, Y. Thigh and Psoas major muscularity and its relation to running mechanics in sprinters. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 50, 2085–2091 (2018).

Handsfield, G. G. et al. Adding muscle where you need it: Non-uniform hypertrophy patterns in elite sprinters. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 27, 1050–1060 (2017).

Hug, F. et al. Selective training-induced thigh muscles hypertrophy in professional road cyclists. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 97, 591–597 (2006).

Kawama, R. et al. Muscle morphological changes and enhanced sprint running performance: A 1-year observational study of well-trained sprinters. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 24, 1228–1239 (2024).

Rønnestad, B. R., Hansen, E. A. & Raastad, T. Effect of heavy strength training on thigh muscle cross-sectional area, performance determinants, and performance in well-trained cyclists. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 108, 965–975 (2010).

Takahashi, K., Kamibayashi, K. & Wakahara, T. Gluteus and posterior thigh muscle sizes in sprinters: Their distributions along muscle length. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 22, 799–807 (2022).

Takahashi, K., Kamibayashi, K. & Wakahara, T. Relationship between individual hip extensor muscle size and sprint running performance: Sprint phase dependence. Sports Biomech., 1–13 (2023).

Tottori, N. et al. Trunk and lower limb muscularity in sprinters: What are the specific muscles for superior sprint performance? BMC Res. Notes 14, 1–6 (2021).

Gajer, B., Hanon, C. & Thepaut-Mathieu, C. Velocity and stride parameters in the 400 metres. New. Stud. Athl. 22, 39 (2007).

Hanon, C. & Gajer, B. Velocity and Stride parameters of world-class 400-meter athletes compared with less experienced runners. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 23, 524–531 (2009).

Ito, A., Fukuda, K. & Kijima, K. Mid-phase sprinting movements of Tyson gay and Asafa Powell in the 100-m race during the 2007 IAAF world championships in athletics. Bull. Stud. Athl. JAAF 5, 93–96 (2009).

Bini, R. R. & Diefenthaeler, F. Kinetics and kinematics analysis of incremental cycling to exhaustion. Sports Biomech. 9, 223–235 (2010).

Belzunce, M. A., Henckel, J., Laura, A. D., Horga, L. M. & Hart, A. J. Mid-life cyclists preserve muscle mass and composition: A 3D MRI study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 24, 209 (2023).

Bini, R. R., Hume, P. A. & Croft, J. Cyclists and triathletes have different body positions on the bicycle. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 14 (S1), S109–115 (2014).

Zhong, Y., Fu, W., Wei, S., Li, Q. & Liu, Y. Joint torque and mechanical power of lower extremity and its relevance to hamstring strain during sprint running. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 8927415 (2017).

Maeo, S. et al. Greater hamstrings muscle hypertrophy but similar damage protection after training at long versus short muscle lengths. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 53, 825–837 (2021).

Gordon, A. M., Huxley, A. F. & Julian, F. J. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 184, 170–192 (1966).

Wickiewicz, T. L., Roy, R. R., Powell, P. L. & Edgerton, V. R. Muscle architecture of the human lower limb. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 179, 275–283 (1983).

Herzog, W. & ter Keurs, H. E. Force-length relation of in-vivo human rectus femoris muscles. Pflügers Arch. 411, 642–647 (1988).

Holliday, W., Theo, R., Fisher, J. & Swart, J. Cycling: Joint kinematics and muscle activity during differing intensities. Sports Biomech., 1–15 (2019).

Hegyi, A., Goncalves, B., Finni Juutinen, T. & Cronin, N. Individual region- and muscle-specific hamstring activity at different running speeds. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51, 2274–2285 (2019).

Hegyi, A., Csala, D., Péter, A., Finni, T. & Cronin, N. J. High-density electromyography activity in various hamstring exercises. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 29, 34–43 (2019).

Woodley, S. J. & Mercer, S. R. Hamstring muscles: Architecture and innervation. Cells Tissues Organs 179, 125–141 (2005).

Craig, N. P. & Norton, K. I. Characteristics of track cycling. Sports Med. 31, 457–468 (2001).

Schache, A. G., Dorn, T. W., Blanch, P. D., Brown, N. A. & Pandy, M. G. Mechanics of the human hamstring muscles during sprinting. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 44 (4), 647–658 (2012).

Farthing, J. P. & Chilibeck, P. D. The effects of eccentric and concentric training at different velocities on muscle hypertrophy. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 89, 578–586 .

Tayashiki, K., Hirata, K., Ishida, K., Kanehisa, H. & Miyamoto, N. Associations of maximal voluntary isometric hip extension torque with muscle size of hamstring and gluteus maximus and intra-abdominal pressure. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 117, 1267–1272 (2017).

Johnson, D., Buckley, J. G. & M. & Muscle power patterns in the mid-acceleration phase of sprinting. J. Sports Sci. 19, 263–272 (2001).

Ikai, M. & Fukunaga, T. Calculation of muscle strength per unit cross-sectional area of human muscle by means of ultrasonic measurement. Int. Z. Angew. Physiol. 26, 26–32 (1968).

Judge, L., Moreau, C. & Burke, J. Neural adaptations with sport-specific resistance training in highly skilled athletes. J. Sports Sci. 21, 419–427 (2003).

Piccoli, M. B. et al. Innervation zone locations in 43 superficial muscles: Toward a standardization of electrode positioning: Innervation zone location and sEMG. Muscle Nerve 49, 413–421 (2013).

Saitou, K., Masuda, T., Michikami, D., Kojima, R. & Okada, M. Innervation zones of the upper and lower limb muscles estimated by using multichannel surface EMG. J. Hum. Ergol. 29, 35–52 (2000).

Vieira, T. M. & Botter, A. The accurate assessment of muscle excitation requires the detection of multiple surface electromyograms. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 49, 23–34 (2021).

Hegyi, A. et al. Superimposing hip extension on knee flexion evokes higher activation in biceps femoris than knee flexion alone. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 58, 102541 (2021).

Selkowitz, D. M., Beneck, G. J. & Powers, C. M. Comparison of electromyographic activity of the superior and inferior portions of the gluteus maximus muscle during common therapeutic exercises. J. Orthop. Sport Phys. 46, 794–799 (2016).

Keerasomboon, T., Mineta, S. & Hirose, N. Influence of altered knee angle and muscular contraction type on electromyographic activity of hamstring muscles during 45 hip extension exercise. J. Sci. Med. Sport 19, 630 (2020).

Hermens, H. J. et al. European recommendations for surface electromyography. Roessingh Res. Dev. 8, 13–54 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participants for their participation and the coaches for their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY, TN, NW, WF, MM and MO conceived and designed research; YY., NW and OM performed experiments; YY, NW and MO analyzed data; YY and OM interpreted results of experiments; YY and OM prepared figures; YY drafted manuscript; YY, NW and MO edited and revised manuscript; All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, Y., Nishiyama, T., Wada, N. et al. Different morphology and function of hip extensor muscles between sprint runners and sprint cyclists. Sci Rep 15, 16372 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98231-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98231-5