Abstract

Mental disorders represent a critical global health challenge that affects millions around the world and significantly disrupts daily life. Early and accurate detection is paramount for timely intervention, which can lead to improved treatment outcomes. Electroencephalography (EEG) provides the non-invasive means for observing brain activity, making it a useful tool for detecting potential mental disorders. Recently, deep learning techniques have gained prominence for their ability to analyze complex datasets, such as electroencephalography recordings. In this study, we introduce a novel deep-learning architecture for the classification of mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, or anxiety, using electroencephalography data. Our proposed model, the multichannel convolutional transformer, integrates the strengths of both convolutional neural networks and transformers. Before feeding the model as low-level features, the input is pre-processed using a common spatial pattern filter, a signal space projection filter, and a wavelet denoising filter. Then the EEG signals are transformed using continuous wavelet transform to obtain a time-frequency representation. The convolutional layers tokenize the input signals transformed by our pre-processing pipeline, while the Transformer encoder effectively captures long-range temporal dependencies across sequences. This architecture is specifically tailored to process EEG data that has been preprocessed using continuous wavelet transform, a technique that provides a time-frequency representation, thereby enhancing the extraction of relevant features for classification. We evaluated the performance of our proposed model on three datasets: the EEG Psychiatric Dataset, the MODMA dataset, and the EEG and Psychological Assessment dataset. Our model achieved classification accuracies of 87.40% on the EEG and Psychological Assessment dataset, 89.84% on the MODMA dataset, and 92.28% on the EEG Psychiatric dataset. Our approach outperforms every concurrent approaches on the datasets we used, without showing any sign of over-fitting. These results underscore the potential of our proposed architecture in delivering accurate and reliable mental disorder detection through EEG analysis, paving the way for advancements in early diagnosis and treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental disorders represent a spectrum of conditions that profoundly impact individuals’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning1. These disorders encompass a wide range of clinically significant conditions, including, but not limited to, depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The global burden of mental illness is staggering, with an estimated one in eight people in the world being affected by mental or neurological disorders, according to the World Health Organization. Despite advances in the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of mental disorders, significant challenges persist2,3. One of the foremost challenges is the subjectivity inherent in traditional diagnostic methods, which rely heavily on self-reported symptoms and clinician observations4. This subjectivity often leads to misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, and inadequate management of these conditions. Such self-reported mechanisms also have inherent human bias.

Assessment techniques for mental disorders have evolved over the years, with a growing emphasis on identifying objective biological markers to complement traditional symptom-based approaches5. Electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and other neuroimaging techniques have emerged as valuable tools to uncover the underlying neural correlates of mental illness. These methods provide insights into the brain’s electrical activity, functional connectivity, and structural abnormalities associated with various psychiatric conditions6,7,8.

Through the real-time collection of physiological data, there has been an emphasis on advancing the development of more precise and reliable diagnostic biomarkers, which can improve our understanding of mental disorders and guide the implementation of personalized treatment approaches. Hence, analyzing the physiological signals and brain connectivity could lead to reliable diagnostic biomarkers which are related to the underlying brain function. This could enhance our understanding of mental disorders leading towards personalized treatment strategies.

In recent years, the intersection of modern computing methods and neuroscience has paved the way for innovative computational approaches to mental health assessment and diagnosis9,10,11. Machine learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL)-based methods, in particular, have shown significant potential in analyzing complex data sets, including EEG recordings. Multichannel EEG data is difficult to analyze due to its high dimensionality, with each channel recording representing complex and dynamic brain signals. The presence of noise from various sources further complicates the extraction of meaningful patterns. Additionally, the non-linear nature of EEG signals requires advanced computational methods to identify relevant temporal and spatial features. Using large-scale datasets along with ML and DL models could offer new avenues for early detection, subtype classification, and prediction of treatment response in psychiatric populations12,13,14. Particularly, the integration of deep learning-based predictive models into clinical practice holds promise for revolutionizing mental health care by allowing more precise and timely interventions tailored to individual patient needs15. However, the complexity and variability of EEG signals, both within and between subjects, make it difficult to generalize models across different datasets.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are machine learning classifiers that have found widespread applications in bioinformatics due to their high accuracy and ability to handle a large number of predictors. Unlike traditional classifiers that separate classes using a hyperplane within the predictor space, SVMs extend this concept to non-linearly separable data by mapping predictors onto a higher-dimensional space where linear separation becomes possible. The process of determining the optimal decision boundary is formulated as an optimization problem, utilizing a kernel function to perform non-linear transformations of the predictors. A study16 has shown that SVMs achieve performance comparable to classical deep learning models. According to this study, deep learning models that rely on backpropagation can suffer from slow convergence and potentially higher testing errors compared to SVMs. However, SVM can also be computationally expensive, especially on very large datasets. For large and complex datasets, it is required to select the correct kernel, which can increase the complexity and the computational cost.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) serve as a deep learning alternative to SVMs, offering a powerful approach for automatically extracting spatial and hierarchical features from input data, particularly images and time-series signals, through convolutional layers. These architectures efficiently identify patterns such as edges and textures, making them well-suited for EEG classification. Initial studies17 have demonstrated that transforming EEG signals into spectral images while preserving their topological structure yields promising results. This success is attributed to CNNs’ ability to capture meaningful information within the spectral representation of EEG data. However, a key challenge of CNN-based models is their need for multiple layers to achieve high accuracy, which significantly increases both model complexity and computational cost.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have emerged as a powerful tool for EEG classification due to their ability to capture temporal dependencies in sequential data. Unlike traditional machine learning models, RNNs possess a “memory” of past inputs, allowing them to learn complex patterns and relationships within EEG signals. This is particularly advantageous in EEG analysis, where the temporal dynamics of brain activity play a crucial role in identifying various neurological states and events. Studies18 have shown that RNN-based models, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), can achieve state-of-the-art performance in diverse EEG classification tasks, including seizure detection, sleep stage classification, and motor imagery recognition. Training RNN is prone to vanishing and exploding gradients problems, which can hinder the learning process.

The field of natural language processing (NLP) has experienced remarkable advancements with the introduction of Transformer models. These architectures scale efficiently, making them highly versatile and increasingly popular in computer vision and audio processing. By utilizing self-attention mechanisms, Transformers can process entire sequences in parallel, enhancing both training efficiency and the ability to dynamically focus on relevant parts of the input. A recent survey19 comparing various Transformer-based approaches concluded that Transformers outperform recurrent neural networks (RNNs) in terms of accuracy. However, the computational cost of self-attention remains a significant challenge. Additionally, Transformers require large datasets to generalize effectively, as their embedding mechanisms depend on extensive data for optimal performance.

In view of the different approaches proposed to classify EEG signals, it is possible to consider that a combination of different modern approaches can help to enhance EEG classification. Especially, we hypothesize that the integration of convolutional layers for localized feature extraction and transformer-based architectures for long-range temporal modeling will enable robust and generalized classification of mental disorders and psychological states from EEG data. We also suppose that using local features can also help to reduce the number of EEG channels required to obtain an accurate model.

Understanding and accurately classifying mental disorders and psychological states from EEG data remains a significant challenge in computational neuroscience and clinical applications. While DL models have shown promise in EEG-based classification tasks, their ability to generalize across diverse datasets with varying clinical and psychological objectives is still under-explored. This study seeks to address two key questions:

-

How can novel DL architectures improve the classification of mental disorders and psychological states from EEG data?

-

Can a novel DL model generalize effectively across datasets with different clinical and psychological objectives?

By investigating these questions, we aim to develop a robust and adaptable model that enhances diagnostic accuracy and supports broader clinical applications with these contributions:

-

A preprocessing pipeline that reduce noise and transform the EEG signal into a 2D time-frequency representation using wavelet transform.

-

A novel multichannel convolutional transformer (MCT) encoder that effectively extract features for each EEG channel, without requiring a large dataset.

-

A fusion method to fuse information from all the channels while preserving information.

-

An entropy-based loss function that enhances the accuracy of the model predictions.

In this paper, we propose a deep learning-based approach for detecting conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression using EEG recordings. Our method utilizes an efficient preprocessing pipeline designed to minimize artifacts and noise captured during data collection, ensuring high-quality input for the subsequent stages of feature extraction and classification. The approach incorporates a state-of-the-art deep learning model that combines convolutional layers with Transformer encoder, leveraging the complementary strengths of both CNNs and Transformers. Although our architecture is designed to classify healthy subjects from subjects who suffer from mental disorders, it is intended to be a step forward rather than a definitive solution, contributing to the ongoing research in this challenging field.

In the “Results” section, the performance of our model is detailed, as well as the effectiveness of our preprocessing method. In the “Discussion” section, the potential theoretical and physical limitations of our approach are discussed. In the “Conclusion” section, we conclude our work and explain our plan for future work. In the “Methods” section, we present the details of our experiments, the datasets used in our experiments, the different elements of our preprocessing pipeline, and the sub-components of our model.

Overview diagram of our model’s architecture. The model is fed with a scaleogram, the result of a continuous wavelet transform, as low-level features, to predict if a subject has been diagnosed with a mental disorder. The model is composed of convolutional, transformer, sequence pooling, and fusion blocks.

Results

EEG signal pre-processing

All stages of the pre-processing pipeline are presented in detail in the section “Pre-processing”. The input EEG signals are pre-processed to enhance and facilitate the machine learning phase. Raw signals have inherent artifacts and noise components that make it difficult to analyze the signal. Reducing undesirable components allows the model to focus on the signal of interest and extract relevant features. Through our innovative prepossessing pipeline, the signals have an attenuation of 17.4 dB on average, across all channels.

The first filter, the Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) filter, attenuates on average the signal by 12.32 dB. This type of filter maximizes the variance between two different classes of signals. By optimizing spatial filters to enhance discriminative features, CSP effectively attenuates irrelevant noise and artifacts that do not contribute to class distinction. The second filter, the Signal Space Projection (SSP) filter projects the signals into another subspace orthogonal to the undesirable components. This filter attenuates the signal by 11.74 dB on average. The third and last step is to denoise the signals using wavelets. By erasing small components from the wavelet transform, this method shows an attenuation of 6.64 dB on average. Table 1 summarizes the effectiveness of each filter per channel. It can be noted that the most effective filters are the CSP and SSP filters. These 2 filters process signals in 2D by analyzing patterns across all channels. Another point to highlight is that some signals become correlated after being passed through the pipeline. experiments shows that the signals from the Fz and F3 channels are highly correlated with a Pearson coefficient of 0.83 after processing versus 0.38 before processing.

Overall, our pre-processing stage plays a critical role in enhancing the efficacy of noise removal techniques for subsequent analysis. Performing pre-processing in both 2D and 1D domains offers distinct advantages. Analyzing the signal in 2D allows for the visualization and identification of common noise patterns like power line interference or muscle artifacts. Figure 2 shows the GRADCAM method20 applied to a scaleogram input. In the input scaleogram, the (B) image, the energy seems to be centered on high frequency. In the heatmap produced by the GRAD-CAM method, the (A) image, it can be noted that the activation function of the last convolutional layers are also focused on the high frequency. This is particularly useful for manual removal or the development of targeted filtering techniques. Conversely, pre-processing in 1D enables the application of signal-specific denoising algorithms along the temporal dimension. By combining 2D and 1D preprocessing steps, more reliable signals are obtained.

Comparison between the input scaleogram (B), and the activation of the last convolution layer for embedding, using the GRAD-CAM method (A). Notably, the activation highlights the portion of the signal where energy is concentrated, suggesting that the embedding likely emphasizes the high-energy frequency band.

Mental disorder classification

Overall our proposed approach has been trained and tested on 1029 different subjects across the three different datasets. We achieved an accuracy of 92.28, 89.84, and 87.40% on the EEG Psychiatric dataset, the Multi-modal Open Dataset for Mental-disorder Analysis dataset, and the EEG Psychological assessment dataset, respectively. Our method demonstrated superior results compared to other approaches, on the same datasets with up to 4.69% increase in accuracy . The details of the dataset used in our approach are detailed in the Section “Experimental datasets”.

For the EEG Psychiatric dataset21, our approach shows an accuracy of 92.28%, a precision of 90.52%, a recall of 90.73% and a F1-score of 90.62% to detect six types of mental disorders: schizophrenia, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, addictive disorder, and stress-related disorder. The second best approach demonstrates an accuracy of 90%, a precision of 89.8%, a recall of 90%, and aF1-score of 89.89%, using an Long-Short term memory (LSTM)-based model, while the baseline model21 has an accuracy of 87.59% using an Elastic Net22. These results show that approaches that can process data in a sequential manner are more effective. Indeed, LSTM and Transformer models can comprehend dependencies and dynamics that are inherent to the data, while the baseline approach uses hand-crafted features that may not represent the underlying dynamics of the data. One of the key reasons our approach outperforms the LSTM model is the demonstrated superiority of Transformer models over RNNs, such as LSTMs, due to their use of the attention mechanism to capture long range dependencies. Additionally, the effectiveness of our method is further enhanced by our data transformation process. 1D signals are being transformed into 2D signal showcasing a time-frequency representation of the data. In23, a particle swarm optimisation algorithm was used to select, and reduce the number of features, while our proposed approach transforms the data into a time-frequency representation using continuous wavelet transformation. Our wavelet transformation effectively preserves the essential information within the data, by showcasing the frequency gain at each time step, making it highly relevant for identifying meaningful patterns in the signal.

To detect depression, our model demonstrates an accuracy of 89.94% on the MODMA21 dataset, while the second-best approach shows an accuracy of 89.63%. The two best approaches leverage the use of convolutional layers combined with blocks that can process data sequentially. This reinforces our hypothesis that convolutional layers are well-suited for embedding input signals, as they leverage localized receptive fields and weight sharing to efficiently capture spatial and temporal dependencies within the data. By focusing on small, overlapping regions of the input, convolutional layers are able to detect meaningful patterns. An exemple of the activation of the last convolutional layer for the embeding is shown in Fig. 2. In addition, combining convolutional layers with a Transformer encoder allows us to effectively capture long-range dependencies and global relationships across the entire input. Our model is superior while using fewer channels as shown in Table 2 The performance of different approaches is summarized in Table 2.

For the EEG and psychological assessment dataset29, our model achieved an accuracy of 87.4%. Given the absence of previously established approaches or benchmarks on this dataset for a similar task, we evaluated our model against other state-of-the-art models. The ResNet5028 emerged as the second-best performer, with an accuracy of 86.94%, followed by the Vision Transformer (ViT)26 with an accuracy of 86.83%, and the LSTM27 model with an accuracy of 74.62%. Detailed results can be found in Table 2. The results show that the MCT accuracy is close to the ViT model and the ResNet. Classic transformer models use an embedding method that requires large datasets. However, using convolutional layers reduces the amount of data necessary to obtain a robust representation, which explains why the MCT and ResNet50 demonstrate higher accuracy.

In general, the results obtained present our model as the best performing in detecting multiple conditions associated with mental disorders. Its key strength relies on the utilization of self-attention mechanisms.

Unlike recurrent or convolutional architectures used in conventional DL-based methods, transformers can attend to any part of the input sequence simultaneously, allowing them to capture long-range dependencies more effectively. In our case where input data are scaleograms (the result of a wavelet transform), finding patterns by looking for dependencies between multiple frequency bands, shows great results.

The performances of our approach on all datasets is summarized in Table 3, and the hyperparameters are shown in Table 4. It can be highlighted that the accuracy metric is systematically higher than others metrics. A 3-fold validation experiment has also been conducted to observe the consistency of our approach. Three folds were chosen instead of five due to the size of the datasets. On the MODMA dataset, our model shows a top accuracy of 89.88% with a mean of 89.83%, with a standard deviation of 0.024. On the EEG Psychiatric dataset, our model shows a top accuracy of 92.29%, with a mean accuracy of 92.28%, and a standard deviation of 0.002. Finally, on the EEG and Psychological Assessment dataset, our model shows a top accuracy of 87.43%, a mean accuracy of 87.42%, and a standard deviation of 0.018. These results demonstrate the capacity of our model to extract and learn on relevant features, and its great ability to adapt.

The accuracy plot of our model on the MODMA dataset is shown in Fig. 3. These plots show no signs of overffiting. The confidence intervals in the first plot don’t tend to explode, meaning that both training loss and validation loss converge.

Ablation study

In order to assess each module’s function and influence within our suggested model, an ablation study is provided in this section. Our objective is to identify each component’s unique contribution to the model’s overall performance by methodically eliminating it. This analysis sheds light on how each module including convolutional layers, the sequence pooling module and the fusion block affect the model’s capacity to efficiently classify EEG data. The study’s conclusions emphasize how crucial each architectural decision is.

In this section, the impact of the parameter from our pre-processing filters are also analyzed. For both CSP ans SSP filters, an analysis of the attenuation in function of the parameters is provided.

Histogram of the performances of the model without some specific modules. The x-axis is the model configuration, the y-axis is the accuracy. The label ’no_conv’ stands for no convolution layer, the label ’no_seq_pool’ stands for no sequence pooling module, and the label ’no_fusion’ stands for no fusion module. This experiment was conducted on the MODMA dataset. The most important module seems to be the convolutional layers.

Figure 4 shows an histogram of ther performances of the model in different configurations. For each configuration, a module has been taken out.Without convolution layers, the model shows an accuracy of 79.62%, without sequence pooling module, the model shows an accuracy of 86.59%, and without fusion module the model shows an accuracy of 84.27%.

When the convolution layers were taken out, they were replaced by a classical ViT embedding module26. ViT-based models divide a 2D-array into patches, which are then linearly projected into embeddings. These patch embeddings, along with a positional encoding to retain spatial information, are fed into a Transformer encoder, where self-attention mechanisms allow the model to learn relationships between different parts of the image and form a rich representation. This method is efficient when the model can be train on large datasets. In our case, using convolutional layers allows the model to naturally learn hierarchical features. The inductive bias allows to directly exploit spatial features. In our cases, inputs are scaleograms. Using convolutional layers for the embedding allows to extract local patterns and capture time-frequency relationships. Convolutional layers are also invariance to shift by design, meaning slight shifts in the timing of a particular frequency component doesn’t alter the signal representation.

The sequence pooling and fusion modules seems to have less impact on the performances. The sequence pooling and fusion modules primarily condense information from embeddings into a fixed-length representation, which, while useful for downstream tasks, does not contribute to the initial feature extraction process. As a result, it can be deduced that the quality of the embeddings generated by the convolutional layers has a more significant impact on the model’s overall performance.

Figure 5 shows how the attenuation from the CSP filter evolves in function of the number of samples \(t_2\) in the second window. When the number of samples in the second window is above 65% of the original signal, the attenuation achieves 12.32dB. It can be noted that the relation between the attenuation and the number of samples seems linear.

Regarding the SSP filter, the key point is the computation of the \(P_{\perp }\) matrix. In our implementation, we used the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reshape and quickly obtain the elements of the matrix31. We compared using PCA to Independent Component analysis (ICA)32 and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)33.

When using PCA, the SSP filter achieves an average attenuation of 11.74 dB, compared to 10.93 dB with ICA and 3.95 dB with SVD. This highlights PCA as the most effective algorithm for computing the orthogonal matrix. EEG signals often exhibit significant noise and redundancy across multiple channels, making it difficult to extract meaningful patterns. PCA addresses this challenge by projecting the data into a lower-dimensional space along the principal components, which represent the directions of maximum variance in the signal, facilitating the construction of \(P_{\perp }\). In contrast, other methods yield lower attenuation results, as some signals lack a decomposition that allows for the proper construction of \(P_{\perp }\).

Discussion

Although our approach shows promising results, some theoretical and physical limitations due to the use of some modules and techniques should be taken into consideration. The first limitation can be the use of different datasets. As explained in the section “Experimental datasets”, three datasets are used to train and test our model. EEG signals are inherently device-agnostic, variations in electrode configurations, impedance levels, and reference electrode placements across different headsets can introduce systematic biases into the data. These inconsistencies arise due to differences in the physical design and technical specifications of EEG devices, such as the number of channels, electrode material, and spatial arrangement, which can lead to variations in signal quality and measurement precision. Consequently, these variations pose challenges for generalization.

The second limitation can be the choice of wavelet transform. The Morlet wavelet is the one that is used to transform the signals. To design this wavelet, it is necessary to select the proper center frequency and bandwidth. The Welch method34, a signal processing technique used to estimate the power spectral density of a signal, has been used to find the best overall parameters for our wavelet. Having a dedicated wavelet per dataset or per EEG recording might be more suitable, but this process would make generalization impossible for the model, and introduce biases.

Despite the fact that the datasets employed in this study are carefully balanced across classes, the accuracy of the proposed model consistently exceeds its precision and recall scores. This observation indicates that, although the model achieves a high proportion of correct predictions overall, it exhibits limitations in correctly identifying positive instances (precision) and in capturing all relevant positive cases (recall). Such a pattern may suggest that the model, while effective at distinguishing between classes on a broad level, faces challenges in handling cases at the decision boundary or in fully leveraging the distinguishing features of the positive class.

To apply our proposed approach in real-world clinical settings to support PTSD diagnosis, it is crucial to train the model on a larger, more diverse datasets that includes a wide range of mental disorders severity levels and varied responses from individuals. This diversity enables the model to capture the extensive variability in symptoms exhibited by different patients, as PTSD manifests uniquely across individuals, with differing symptom intensity and combinations. By incorporating data that reflects these variations, our model can better learn to recognize and predict a broader spectrum of symptom profiles, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of assessments. Integrating this variability with in-the-wild data through transfer learning or fine-tuning is expected to further increase the model’s robustness, improving its performance in both controlled and real-world environments.

Another limitation might be the fusion block. Our fusion process uses the Hadamard product35. This makes the fusion very sensitive. If the data is corrupted, the prediction might not be relevant.

Using attention to capture dependencies is effective but not efficient as it scales quadratically with the input length, in addition to the size of the model. This huge demand for hardware resources makes it difficult to scale the model even more. In our context, analyzing both local and global patterns within the data proves to be an efficient approach. Local patterns capture rapid changes in frequency or intensity, potentially indicative of specific events or features of interest. Conversely, global patterns highlight broader trends and dominant frequency bands that characterize the overall structure of the scaleogram. We have concentrated on 5 channels. Using different channels affects performances.

To demonstrate generalizability and robustness from our proposed model, we utilized datasets with varying purposes. This diversity highlights the model’s ability to perform effectively across different, yet related, clinical and psychological applications. By validating the model’s performance on datasets with differing objectives, we illustrate its flexibility and potential for broader clinical adoption. Specifically, the results indicate that the model is not overfitted to a single task but is instead capable of addressing a wide range of challenges associated with EEG signal analysis, thereby underscoring its suitability for real-world applications. Although the results indicate the method’s effectiveness for this particular dataset, its generalizability to other datasets remains an open question and a key area for further exploration.

Our results highlight the model’s remarkable ability to generalize effectively across three diverse EEG datasets, each tailored to distinct clinical and psychological objectives. By leveraging a novel deep learning architecture, our model effectively captures both short and long-range dependencies in EEG signals, allowing it to adapt to varying data distributions while maintaining high classification accuracy. The results indicate that, despite the inherent challenges in EEG-based mental disorder classification, our approach remains robust and achieves consistent performance.

Our approach has great accuracy with few EEG channels, making it highly practical for clinical applications. By reducing the number of channels needed while maintaining high accuracy, our model minimizes setup complexity and enhances accessibility for clinicians, enabling more efficient and scalable mental health assessments. Additionally, the success of our method highlights the potential for similar deep learning architectures to be applied to related problems in EEG analysis, inspiring future research toward more lightweight, effective, and generalizable models for neurological and psychological diagnostics.

In medical data classification, accuracy, precision nd recall are gold standards metrics to evaluate an approach. Accuracy measures the overall correctness of predictions but can be misleading when dealing with imbalanced datasets (e.g., a rare disease). Precision focuses on how many of the positive predictions were actually correct, minimizing false positives (e.g., incorrectly diagnosing someone with a disease). Recall, on the other hand, measures how well the model identifies all actual positives, minimizing false negatives (e.g., missing a diagnosis). The F1-score balances precision and recall, providing a single metric that considers both. In medical applications, the relative importance of precision and recall depends on the specific context. In our case, having a high precision can be prioritized to minimize the psychological and financial burden of false positive results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we presented a deep learning-based approach to detect various mental disorders including depression, schizophrenia, anxiety stress-related disorders, or addictive disorders. A cutting-edge pre-processing pipeline that processes data in 2D and 1D has been implemented to attenuate noise and artifacts that appeared during data collection. This pipeline attenuates the signal up to 17.53 dB. Our approach leverages the use of a Multichannel Convolutional Transformer to learn local and global features. This deep learning model uses convolutional layers to tokenize and embed the input, while the Transformer block captures dependencies on the embedded signal. The model is also composed of a Sequence Pooling block, that pools the token from the latent space in order to keep a robust and relevant representation of the input data, and a Fusion block that uses algebraic operations and a sub-model to fuse data from all the channels and obtain global features. Through our approach, we achieved 87.4% accuracy on the EEG Psychiatric dataset, 84.2% accuracy in depression detection, and 87.40% for the detection of PTSD. Findings indicates that our approach can generalize across different datasets with different objectives. Our model is suitable to assist clinicians in the diagnosis of multiple mental disorders. For future work, we plan to investigate the use of other physiological signals such as ECG, and to incorporate them in a multimodal approach. Future research could evaluate an enhanced model on larger datasets to further validate its generalization and robustness. We also plan to investigate how our approach can be used as a base to develop a real world approach.

Methods

Experiments design

Our objective is to detect patients who have been diagnosed with mental disorders. Figure 1 shows an overview of our model and its component. Our model has been trained to detect patients who have been diagnosed with mental disorders from the control subjects who have been diagnosed as neurotypical individuals. Depending on the dataset, the detection is performed in the form of binary classification in a yes/no format, or a classification of multiple mental disorders. For our experiments, our model has been trained and evaluated on 3 datasets containing EEG data from different subjects. Each dataset is focused on one mental disorder. These datasets are acquired within controlled environments, yet exhibit variance in their content and context. The first dataset encompasses records obtained from individuals diagnosed with PTSD, and engaged in structured exercises designed to evaluate their physiological responses and recuperative progress. The second dataset contains data on subjects affected by depression. Subjects were asked to place themselves in a resting state.

All necessary permissions and licenses were obtained to access and utilize the datasets employed in this research. These permissions were granted by the respective data providers and adhere to their specific terms and conditions of use.

To train and test our model, 4 NVIDIA V100 GPUs with 32GB of VRAM each have been used. All data have been pre-processed using 4 INTEL XEON CPUs. For all data sets, the split between train/validation/test has been 75%/15%/10%. No subject present in a fold, is present in another fold to avoid over fitting.

Experimental datasets

To train and evaluate our model, we utilized three publicly available EEG datasets, each containing labeled EEG recordings from both healthy control subjects and individuals diagnosed with various mental disorders. These disorders include mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, schizophrenia, and depression. The inclusion of multiple datasets allows us to assess the generalizability and robustness of our model across different clinical conditions and experimental settings.

Each dataset provides two types of labels: continuous labels and categorical labels. Continuous labels correspond to the scores assigned to subjects based on self-reported psychological assessments, primarily using standardized mental health evaluation tools such as the PCL-5 questionnaire36. These scores provide a quantitative measure of symptom severity, enabling a more nuanced understanding of an individual’s mental state. In contrast, categorical labels are discrete values indicating whether a subject has been diagnosed with a specific mental disorder. These labels enable classification tasks where the goal is to distinguish between different diagnostic categories or identify the presence of a disorder.

A detailed analysis of the label distributions is presented in Fig. 6. While the datasets exhibit a relatively even balance between healthy and diagnosed subjects, they are not perfectly balanced in terms of symptom severity representation. The distributions of the continuous labels, derived from questionnaire scores, are non-uniform and vary significantly across datasets. This imbalance suggests that certain severity levels are underrepresented, which may pose challenges for machine learning models, particularly in recognizing edge cases and rare conditions. Traditional models may struggle to generalize across the entire spectrum of symptom severity, potentially leading to biases in classification performance.

Moreover, the nature of the EEG recordings, including differences in acquisition protocols, electrode placements, and preprocessing techniques, introduces additional variability across the datasets. This diversity, while beneficial for testing model robustness, also necessitates careful preprocessing and normalization to ensure comparability.

In the following subsections, we provide a detailed description of each dataset, outlining their sources, participant demographics, data collection methodologies, and label distributions.

Kernel density estimation of the scores from the mental health questionnaires. (A) is a study of the EEG and psychological assessment dataset, (B) is a study of the MODMA dataset. In both figures, the bar represents the discrete plot, where the continuous line is the density estimation of the smoothed distribution. These estimations show that the data is not distributed uniformly.

EEG psychiatric dataset

This dataset21 intends to support the development of machine learning models developed by researchers using EEG to identify major psychiatric disorders37. Information is gathered from medical records, including EEG recordings during resting-state assessments, and intelligence quotient (IQ) scores from psychological tests. The dataset consists of 95 healthy control subjects and 850 patients with major psychiatric disorders. The ages of the subjects range from 18 to 70 years. Nineteen channels were used in the acquisition of the signal. Labels are unique categorical labels that refer to mental disorders including schizophrenia, mood disorder, anxiety, compulsive disorder, addictive disorder, stress-related disorder, and healthy control.

Regarding the subjects of this datasets, their initial diagnostic was made by a psychiatrist based on DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria and further evaluated using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview during psychological assessments. The final confirmation of the primary diagnosis was conducted by a team of two psychiatrists and two psychologists. he inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: individuals aged 18 to 70 years with a primary diagnosis falling into one of six broad diagnostic categories, encompassing nine specific mental disorders. These included schizophrenia (n = 117), mood disorders [(n = 266), comprising depressive disorder (n = 119) and bipolar disorder (n = 67)], anxiety disorders [(n = 107), including panic disorder (n = 59) and social anxiety disorder (n = 48)], obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 46), addictive disorders [(n = 186), divided into alcohol use disorder (n = 93) and behavioral addictions such as gambling and Internet gaming disorders (n = 93)], and trauma- and stress-related disorders [(n = 128), consisting of PTSD (n = 52), acute stress disorder (n = 38), and adjustment disorder (n = 38)]. Additionally, all participants were required to have no difficulties in reading, listening, writing, or understanding Hangeul (Korean language). The exclusion criteria included any lifetime or current medical history of neurological disorders or brain injury, as well as neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disability [intelligence quotient (IQ) < 70], borderline intellectual functioning (70 < IQ < 80), tic disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or any neurocognitive disorder.

MODMA dataset

The Multi-modal Open Dataset for Mental-disorder Analysis (MODMA)30 is composed of data from clinically depressed patients and healthy controled subjects. This dataset consists of audio recordings and EEG data. In total, 55 subjects constitute this dataset. Professional psychiatrists in hospitals carefully diagnose and choose each patient. The EEG signals were captured during both periods of activity and rest. The EEG dataset contains information from both a novel wearable 3-electrode EEG collector intended for widespread applications and data obtained using conventional 128-electrode-mounted elastic caps. Speech data was recorded during picture description, reading, and interview tasks. The labels are categorical and refer to two classes: healthy and depressed.

All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) were recruited from both inpatient and outpatient services at Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Gansu, China, based on diagnoses confirmed and recommended by at least one clinical psychiatrist. Normal control (NC) participants were recruited through public advertisements. The inclusion criteria for all participants required them to be between 18 and 55 years old and have at least a primary education level. For MDD patients, additional inclusion criteria included meeting the diagnostic standards for depression according to the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score of 5 or more, and no psychotropic drug treatment within the past two weeks. Exclusion criteria for MDD patients included a history of other mental disorders or brain injuries, severe physical illnesses, or extreme suicidal tendencies. For NC participants, exclusion criteria involved a personal or family history of mental disorders. Additionally, exclusion criteria for all participants encompassed a history of alcohol or psychotropic substance abuse or dependence within the past year, pregnancy, lactation, or the use of birth control pills.

EEG and psychological assessment dataset

Both psychometric and EEG data are included in this dataset29. The EEG signal values are organized in two-dimensional (2D) matrices in the data, with samples (sampled at a sampling rate of 250 Hz) in columns and channel and trigger information in rows. A psychological evaluation was conducted on 29 female survivors of the 1994 Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi, both prior to and following an intervention designed to reduce the severity of symptoms associated with PTSD. Standardized assessments that have been empirically validated were used to evaluate four measures of well-being and three measures of trauma using the PCL-5, the DSM538, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ)39, the Mental Health WellBeing (MHWB)40, and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)41. 20 channels are used during the recordings.

Preprocessing

Overall diagram of our preprocessing pipeline. The EEG recordings are processed by a CSP filter followed by an SSP filter. The array is then split to filter the signals individually. Once split, the signals are filtered by a WD filter. The WD filters return the signals of interest that will transformed to feed the neural network.

The EEG recordings used in our experiments exhibit variability in sampling rate, impedance of the electrodes, or position of electrodes, as well as the presence of artifacts and noise across different sessions. The multiplicity of contextual nuances led to the development of a pre-processing pipeline aimed at optimizing the signal representation. Noise and artifacts can obscure the underlying neural activity, leading to inaccurate or distorted input data that in turn hampers the ability to learn meaningful patterns within the data using machine learning algorithm. Clean EEG signals ensure that the algorithm can focus on relevant features, improving the accuracy, robustness, and generalization of the model.

EEG recordings are modeled in the form of 2D arrays where each channel is a 1D signal array. This 2D array modeling facilitates comprehensive artifact and noise detection, as these typically manifest simultaneously across multiple channels at specific time points. Thus, by taking this modeling into account, we propose a pre-processing pipeline that aims to remove noise and artifacts as shown in Fig. 7.

Our pre-processing pipeline is composed of three filters: a Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) filter designed to find and attenuate noise and artifact patterns that are common across multiple channels, a signal space projection (SSP) filter to reduce noise and artifacts by projecting the signal onto a subspace orthogonal to the noise sources, and a wavelet denoising (WD) filter that removes noise by decomposing a signal into wavelet coefficients. All three filters are complementary, and all data from the three datasets has been preprocessed using the same pipeline.

Common spatial pattern detection

The first module of our pipeline is a CSP filter42. In signal processing, CSP filters are signal processing techniques that divide a signal into additive subcomponents with the greatest variance variations across multiple windows. Let \(\Omega _1\) and \(\Omega _2\) of shape (n,\(t_1\)) and (n,\(t_2\)) respectively, two windows of a signal, where n is the number of signals, \(t_1\) the number of samples in the first window, and \(t_2\) the number of samples in the second window. This filter aims to determine a component matrix w in a way that maximizes the ratio of variance between two windows:

Where \(argmax_{w}\) is the function that returns the index or position of the maximum value within w. The elements of w can be found by computing two covariance matrices \(Cov_1 = \frac{\Omega _1 \cdot \Omega _1^{T}}{t_1}\) and \(Cov_2 = \frac{\Omega _2 \cdot \Omega _2^{T}}{t_2}\). By a generalized eigenvalue decomposition of these two matrices, it is possible to find a matrix of eigenvectors \(P = [p_1 \quad p_2 \quad \dots \quad p_n]\), and a diagonal matrix D of eigenvalues such that :

In Eq. 3, I is the identity matrix. Once the P matrix is computed, it is possible to obtain w by extracting the first column of P and transposing it. Therefore, we obtain \(w = Pp_1^{T}\). Once w is determined, it is possible to obtain the signal of interest, as shown in Eq. 4, where S is the raw signal, and \(\hat{S}\) is the signal of interest.

Signal space projection

The second module of our preprocessing pipeline is a SSP filter43,44. SSP is a technique for reducing the interference present in the data by projecting the captured signal onto a subspace orthogonal to the interference. When noise is present, the average pattern across signals is calculated, treated as a direction in the signals space, and the subspace is constructed to be orthogonal to the noise direction. This process determines the subspace.

Let’s denote \(X = X_s + X_n\) as the noisy signal matrix where each column represents a single signal channel, B the basis matrix of the subspace, \(\Pi\) as the projection matrix onto the orthogonal complement of the interference subspace. The basis matrix construction process can be obtained through a Principal Component Analysis (PCA). We obtain the directions of maximum variance in the data by extracting the principal axes in the feature space formed by the signals. In equivalent terms, this shows the right singular vectors of the centered input data parallel to its eigenvectors. The projection matrix is calculated as the orthogonal complement of B. If we can find an orthogonal matrix U whose columns are the eigenvectors corresponding to the interference subspace, then we can construct \(P_{\perp }\) as \(P_{\perp } = I - U \cdot U^{T}\), with U the orthogonal matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors corresponding to the interference subspace. From this, we can deduce a decomposition of the interference as \(X_n = U\gamma\), where \(\gamma\) is a random vector representing the interference. The final equation to project the signals and effectively remove the interference is given by:

Wavelet denoising

The final stage of our preprocessing pipeline involves a channel-wise WD procedure45. Wavelets, with their capacity to handle non-stationary data such as EEG signals, are particularly beneficial for preserving important signal features while effectively reducing noise. Unlike traditional frequency-based methods that only analyze frequency, wavelet-based approaches decompose signals into localized components that retain both frequency and time information, enabling targeted noise reduction without compromising the underlying signal integrity. The discrete wavelet transform, central to WD, exploits the sparsity-inducing property when applied to signals. This property results in the concentration of essential signal characteristics within a limited number of significant wavelet coefficients, while coefficients with minimal values typically represent noise. By selectively attenuating these lesser coefficients, we can reduce noise without noticeable degradation to the signal. The process begins by transforming a signal x into its wavelet coefficients using a discrete wavelet transform:

where \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) denote the scaling (low-pass) and wavelet (high-pass) functions respectively, and \(a_k\), \(d_k\) are the approximation and detail coefficients at scale \(j\). Let x be a discrete signal of finite length N, and let \(\mathcal {H} = \{h_i\}^{K}_{i=0}\) be a set of filters for low-pass and high-pass analysis. The convolution of x with a low-pass filter from \(\mathcal {H}\) yields the approximation coefficients, while convolving with a high-pass filter yields the detail coefficients. After obtaining these coefficients, they are subjected to a thresholding function T to mitigate noise:

where \(\lambda\) is a carefully selected threshold parameter, and \(c_{j,k}\) are the coefficients. Following the attenuation of the undesirable coefficients, the denoised signal \(\hat{x}\) is reconstructed through an inverse wavelet transform:

where \(\hat{a}_k\) and \(\hat{d}_k\) are the retained coefficients after thresholding. In our study, we employ the Daubechies wavelet due to its compact support and orthogonality, properties that are particularly suited for capturing the intricate structures within EEG signals. A comparative analysis of various thresholding methods using the minimax algorithm46. This comprehensive approach to WD ensures that the essential characteristics of the EEG signals are preserved while effectively minimizing noise, enhancing the overall quality and reliability of our signal analysis.

Data transformation

To feed data to our model, the data are first transformed into a time-frequency format, so the model can extract and learn relevant features. The transformation is a Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT)47. Because of its capacity to effectively capture the temporal and spectral properties present in neurophysiological data, the continuous wavelet transform is the method of choice. Wavelet transform, in contrast to Fourier-based techniques, provides a more focused approach by dividing signals into time-varying frequency components48. This makes it perfect for the dynamic and non-stationary nature of EEG signals, which represent brain activity.

The transformation utilizes a wavelet to establish a Hilbert basis, which forms a comprehensive orthonormal system within the Hilbert space \(\textrm{L}^{2}(\mathbb {R})\). The set of function {\(\psi _{j;k}: j,k \in \mathbb {Z}\)} constitutes our Hilbert basis, serving as the foundation for our transformation. The wavelet chosen in our approach is the Complex Morlet Wavelet (CMW)49. The CMW \(\psi \in \mathbb {C}\) is given by:

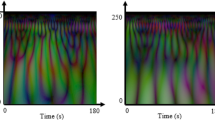

Where \(f_b\) is the frequency bandwidth, and \(f_c\) is the center frequency. The CMW has been chosen for its characteristics. This wavelet’s time and frequency domain representation is Gaussian-like, meaning it has a compact support centered around the dominant frequency while being able to capture both rapid and oscillatory changes in the signals. Its complex nature allows us to capture phase information, an advantage to analyze transient features and oscillatory behavior. Based on these principles, we can calculate the transformation formulated in Eq. 10, where \(W_{x(u,s)}\) represents the wavelet transform of a signal \(x \in \textrm{L}^{2}(\mathbb {R})\) at time and scale u, s. A scaleogram is shown in Fig., showing the result of a wavelet transform.

Model development

In our approach, we develop a novel deep learning model that aims to identify subjects with mental disorders. Our model is a Multichannel Convolutional Transformer (MCT). In contrast to traditional approaches that seek to generalize across all channels, our model extracts unique local features from each channel to then fuse the features. In this study, five EEG channels were considered: Cz, T3, Fz, Fp1, and F3. These channels were chosen because they showed to be the most advantageous.

MCT uses convolutional blocks to tokenize the input data5051 and Transformer encoders that extract features and find patterns. The model is also composed of Sequence Pooling blocks52 that extract the output sequence of tokens from each channel, instead of forwarding query tokens. Then the model uses a fusion block that uses attention to weigh the contribution of each pooled output. An overview diagram of the model architecture is shown in Fig. 1, and all the blocks that constitute our model are detailed in the following subsections.

Convolutional layers for tokenization

Convolutional layers, foundational to our tokenization process, capitalize on three critical concepts: sparse interaction, equivalent representation, and weight sharing53. Unlike the dense interactions in fully connected layers, convolutional filters engage only with specific subsets of the input, focusing on local patterns and efficiently learning hierarchical features54. First convolutional layers detect simpler, global features like edges or textures, while deeper layers discern more complex patterns and shapes. This selective interaction enables convolutional-based models to exploit image statistics effectively, maintaining sampling efficiency. Our model employs a series of convolution operations to tokenize input, thus preserving local information within a scaleogram token. The convolution block consists of a sequence involving a convolutional layer, a fully-connected layer, followed by another convolutional layer, an additional fully-connected layer, and a final convolutional layer. This sequence concludes with a zero-padding layer and a pooling layer, as detailed in Fig. 8. This design introduces an inductive bias into the model, facilitating the learning of relevant features without direct supervision. Given a feature map or scaleogram \(x \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times F \times 1}\), the output \(x_0\) of the convolution block can be mathematically expressed as:

Here, \(\text {MaxPool}\) denotes the maximum pooling function, \(\text {ZeroPad}\) represents the zero padding function, W is a learnable weight matrix, F signifies a set of filters, and \(*\) denotes the convolution operation. The overlap of padding and pooling operations preserves local spatial information, essential for maintaining the integrity of feature extraction. The convolutional tokenization not only reduces the complexity associated with self-attention, typically \(\mathcal {O}(N^2)\) relative to the number of tokens but also allows for downsampling when necessary without significantly impairing model performance.

The convolutional module processes scaleograms by treating them as structured two-dimensional representations of EEG signals, enabling effective feature extraction at multiple levels. Scaleograms, derived from continuous wavelet transforms, capture both time and frequency information, making them well-suited for convolutional operations. The initial convolutional layers focus on detecting fundamental patterns within the scaleogram, such as localized spectral variations and transient signal characteristics. As the data propagates through deeper convolutional layers, the model extracts increasingly complex features, including higher-order temporal dependencies and frequency-domain structures. The final pooling operation consolidates the extracted information into a compact representation, ensuring that the most salient features are retained before passing the processed tokens to the Transformer encoder for long-range dependency modeling. Convolutional layers can effectively capture both hierarchical and local features, but on its own, these type of layers cannot capture long-range dependencies, which is crucial for EEG data. These layers therefore need to be coupled with other modules such as transformers.

Transformer block

Our Transformer backbone is modeled after the original Vision Transformer (ViT) design principles26, utilizing Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) for projection, attention layers for cross-attention computation, and MultiHead-Attention layers for self-attention computation. These encoders incorporate sinusoidal position embeddings and utilize the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GeLU) activation function. Following the convolutional tokenization stage, the Transformer encoders receive tokenized inputs. These inputs enable the encoders to leverage hierarchical features to construct robust representations. These representations are particularly effective for capturing long-range dependencies and contextual nuances across the entire input spectrum, enhancing the model’s generalization capabilities from training data to unseen instances. The attention mechanism, pivotal to the Transformer’s performance, is described by the following equation:

where Q, K, and V are the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, and \(d_k\) represents the dimensionality of the keys. The model computes both self-attention and cross-attention55, as illustrated in Fig. 8. Self-attention captures local dependencies within the data by enabling each element to interact with others in its immediate neighborhood, thus preserving intricate local patterns. Conversely, cross-attention extends this interaction across different channels, allowing the model to integrate information over the entire data spectrum. These processes are vital for effectively synthesizing local and global data features. The MultiHead-Attention mechanism facilitates a comprehensive feature integration by performing the attention function in parallel across multiple ’heads’:

Where each head i is computed as:

and \(W^O\) is the projection matrix for the output of the concatenated heads. For cross-attention:

where \(Q^i_c\) is the query vector from the i-th channel, \(W^{qi}_c\) is a learnable matrix, \(\text {LN}\) denotes Layer Normalization, and \(z_i\) is the latent vector from the i-th channel. Similarly, the value and key vectors for cross-attention are formulated as:

The integration of self-attention for local feature emphasis and cross-attention for global context enrichment allows the model to construct a detailed and comprehensive representation of the input data. This dual attention mechanism ensures that the model captures both detailed interactions and broader patterns, essential for a deep understanding of complex datasets.

Diagram of the convolutional and transformer blocks. The convolutional block is composed of 3 convolutional layers combined with dense layers. Zero-padding and Max-pooling are then applied. The Transformer block is composed of MultiHead-Attention layers and dense layers. It can be noted that the cross-attention is computed using data from all the channels.

Sequence pooling

Traditional ViT-based models often forward query tokens through fully connected layers before they reach a classifier, sometimes using pooling operations like max-pooling or average-pooling to consolidate token information. While effective in generating robust representations at early layers, these methods can inadvertently result in information loss, particularly when processing 2D data. To address this issue, we introduce the Sequence Pooling block, an attention-based mechanism designed to pool tokens across the output sequence in a manner that is both efficient and parsimonious in parameter usage. This block is particularly adept at extracting and preserving critical information from the input data without significant losses. The operation of the Sequence Pooling block can be described as follows:

where \(x_k\) is the output from the \(k^{th}\) layer of a Transformer, b is the batch size, n is the output length, and d is the embedding dimension. This output is transformed by a dense layer equipped with a softmax function to yield:

Here, \(x_k'\) serves as an importance weighting vector for each input token. By applying these weights to the input tokens, we obtain a latent vector encapsulating the weighted significance of each token:

This method allows the model to dynamically emphasize the most informative tokens, thereby enhancing the network’s ability to discern and prioritize relevant information across diverse datasets.

Fusion block operations

Our approach integrates a series of advanced algebraic and pooling operations, along with self-attention mechanisms, to optimize the interaction of features and improve the robustness of the model. A detailed illustration of the process within this block is provided in Fig. 9. Algebraic Operations: The first step in our fusion block involves an element-wise product of all latent vectors, which are outputs from the Sequence Pooling block. This algebraic operation enhances the interaction among features by emphasizing co-occurrence:

where Z represents the resultant vector and \(z_i\) are the individual latent vectors. This operation is particularly effective in highlighting strong and concordant features that produce high values when features align well and diminishing those that do not. The element-wise multiplication also maintains dimensionality consistency across vectors, which is crucial for preserving the model’s structural integrity and efficiency. Max-Pooling: Following the algebraic operation, max-pooling is applied:

This pooling method distills the most salient features from the element-wise product, ensuring that the model captures the most critical information. By retaining the most prominent elements, max-pooling minimizes the adverse impact of near-zero values, which could otherwise dilute the model’s effectiveness. MultiHead-Attention: The final step in the fusion block is the application of a MultiHead-Attention (MHA) layer, which follows the max-pooling step. This layer utilizes several attention heads to capture diverse aspects of the input data:

Each attention head independently focuses on different segments of the data, enabling the model to detect complex patterns and nuances that might be overlooked by more straightforward analysis methods. Self-attention compensates for potential information losses that can occur during max-pooling by dynamically integrating features across various contexts. This redundancy ensures that essential data elements are retained and effectively contextualized, providing a robust mechanism for dynamic feature interaction and adaptation to diverse data patterns. Through these steps, the fusion block significantly enhances the model’s ability to process and integrate complex datasets, ensuring that both prominent and subtle data characteristics are effectively captured and utilized in the predictive process.

Fusion block diagram. This Diagram shows the elements that constitute the Fusion block. Latent vectors \(z_i\), which are the pooled sequence from the sequence pooling block, are first fused using the element-wise product. Then the global latent vector \(Z = z_1 \odot \dots \odot z_{i} \odot \dots \odot z_c\) is passed through a multihead-attention layer and a global averaging pooling layer.

Loss function for optimization

Due to the complexity of the data encountered in our study, we have employed various optimization functions to enhance the robustness of model performance. In particular, these functions were originally proposed in the context of Human Activity Recognition in56. This study extends their application for the first time to multichannel convolutional transformers, thereby broadening the utility and demonstrating the adaptability of these optimization strategies in addressing complex data integration challenges in new computational domains.

The initial solution proposed, termed LSE Cross Entropy, involves minimizing the loss of the worst-performing classes using the LSE(x) function. This approach is analogous to minimizing the maximum loss function:

By substituting \(\max (x)\) with the \(\textit{LSE}(x)\) function, the following objective function is derived:

Hence, the objective function can be expressed as:

Here, \(\alpha\) is a weighting coefficient that modulates the influence of individual low-level class loss on the overall classification loss.

The gradient, denoted as \(g:\mathbb {R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^n\), is defined by:

where \(g_j(x)\) is referred to as the Softmax function

The second proposed solution, termed Softmax Cross Entropy, involves minimizing the loss of the worst-performing classes using the Softmax activation function:

Consequently, the objective function can be formulated as:

As previously discussed, Eqs. 25 and 28 focus on minimizing the maximum loss of the worst-performing classes. However, these approaches do not enhance the performance of the other classes.

To address this and consider the losses of all classes, thereby controlling their impact on the overall loss function, two solutions are proposed in (29) and (30):

Here, \(\beta\) is a weighting parameter that adjusts the influence of the second loss term on the total objective function. The term \(\beta \sum _i \mathcal {L}_i(x)\) represents the aggregate loss of all classes.

Thus, by substituting the first term in Eq. (29) with Eq. (25), the third objective function, referred to as the LSE-plus loss function, is formulated as follows:

Similarly, by replacing the activation function Softmax in Eq. (30) with Eq. (27), the fourth objective function, termed the Softmax-plus loss function, is expressed as follows:

Data availibility statement

All necessary permissions and licenses were obtained to access and utilize the datasets employed in this research. These permissions were granted by the respective data providers and adhere to their specific terms and conditions of use. The EEG Psychiatric dataset is available at the address: https://osf.io/8bsvr/. The EEG and Psychological Assessment dataset is available at the address https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/gsxphk87mc/1 The MODMA dataset is available on request for academic and research use only. The request can be done at https://modma.lzu.edu.cn/data/application/

References

Marquand, A. F. et al. Conceptualizing mental disorders as deviations from normative functioning. Mol. Psychiat. 24, 1415–1424 (2019).

Bryant, R. A. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A state-of-the-art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiat. 18, 259–269 (2019).

Rosen, G.M., Frueh, B.C. Challenges to the ptsd construct and its database: The importance of scientific debate (2007).

Regier, D. A. et al. Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders: Implications for research and policy. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 55, 109–115 (1998).

Quinlan, E. B. et al. Identifying biological markers for improved precision medicine in psychiatry. Mol. Psychiat. 25, 243–253 (2020).

Thakor, N. V. & Tong, S. Advances in quantitative electroencephalogram analysis methods. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 6, 453–495 (2004).

Li, Y. et al. A novel eeg-based major depressive disorder detection framework with two-stage feature selection. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 22, 209 (2022).

Khare, S. K., Gadre, V. M. & Acharya, U. R. Ecgpsychnet: An optimized hybrid ensemble model for automatic detection of psychiatric disorders using ecg signals. Physiol. Meas. 44, 115004 (2023).

Singh, J. & Hamid, M. A. Cognitive computing in mental healthcare: A review of methods and technologies for detection of mental disorders. Cogn. Comput. 14, 2169–2186 (2022).

Du, Z. et al. Neuromorphic accelerators: A comparison between neuroscience and machine-learning approaches. In Proceedings of the 48th International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 494–507 (2015).

Han, J. et al. Deep learning for mobile mental health: Challenges and recent advances. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 38, 96–105 (2021).

Jafari, M. et al. Empowering precision medicine: Ai-driven schizophrenia diagnosis via eeg signals: A comprehensive review from 2002–2023. Appl. Intell. 54, 35–79 (2024).

Bdaqli, M. et al. Diagnosis of parkinson disease from eeg signals using a cnn-lstm model and explainable ai. In International Work-Conference on the Interplay Between Natural and Artificial Computation, 128–138 (Springer, 2024).

Shoeibi, A. et al. Diagnosis of schizophrenia in eeg signals using ddtf effective connectivity and new pretrained cnn and transformer models. In International Work-Conference on the Interplay Between Natural and Artificial Computation, 150–160 (Springer, 2024).

Avasthi, S., Sanwal, T., Sareen, P. & Tripathi, S. L. Augmenting mental healthcare with artificial intelligence, machine learning, and challenges in telemedicine. In Handbook of Research on Lifestyle Sustainability and Management Solutions Using AI, Big Data Analytics, and Visualization, 75–90 (IGI global, 2022).

KavitaMahajan, M. & Rajput, M. S. M. A comparative study of ann and svm for eeg classification. Int. J. Eng.1 (2012).

Zhao, X. et al. Deep cnn model based on serial-parallel structure optimization for four-class motor imagery eeg classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 72, 103338 (2022).

Gatfan, S. K. A review on deep learning for electroencephalogram signal classification. J. Al-Qadisiyah Comput. Sci. Math. 16, 137–151 (2024).

Keutayeva, A., Abibullaev, B. Data constraints and performance optimization for transformer-based models in eeg-based brain-computer interfaces: A survey. IEEE Access (2024).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 618–626 (2017).

Park, S. M. et al. Identification of major psychiatric disorders from resting-state electroencephalography using a machine learning approach. Front. Psych. 12, 707581 (2021).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat Methodol. 67, 301–320 (2005).

Basak, M., Maiti, D., Das, D. A hybrid approach of differential evolution and multistage lstm for diagnosis of psychiatric disorder using eeg. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision and Machine Intelligence (CVMI), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVMI59935.2023.10464768 (2023).

Tasci, G. et al. Automated accurate detection of depression using twin pascal’s triangles lattice pattern with eeg signals. Knowl.-Based Syst. 260, 110190 (2023).

Liu, W., Jia, K., Wang, Z. & Ma, Z. A depression prediction algorithm based on spatiotemporal feature of eeg signal. Brain Sci. 12, 630 (2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

DiPietro, R., Hager, G. D. Deep learning: Rnns and lstm. In Handbook of Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention, 503–519 (Elsevier, 2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Du Bois, N. et al. Electroencephalography and psychological assessment datasets to determine the efficacy of a low-cost, wearable neurotechnology intervention for reducing post-traumatic stress disorder symptom severity. Data Brief 42, 108066 (2022).

Cai, H. et al. A multi-modal open dataset for mental-disorder analysis. Sci. Data 9, 178 (2022).

Rusu, C. & Rosasco, L. Fast approximation of orthogonal matrices and application to pca. Signal Process. 194, 108451 (2022).

Lee, T.-W., Lee, T.-W. Independent Component Analysis (Springer, 1998).

Klema, V. & Laub, A. The singular value decomposition: Its computation and some applications. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 25, 164–176 (1980).

Rahi, P. K. et al. Analysis of power spectrum estimation using welch method for various window techniques. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Eng. 2, 106–109 (2014).

Siriwardhana, S., Kaluarachchi, T., Billinghurst, M. & Nanayakkara, S. Multimodal emotion recognition with transformer-based self supervised feature fusion. Ieee Access 8, 176274–176285 (2020).

Weathers, F. W. et al. The ptsd checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). PTSD (2013).

Shen, Z. et al. Aberrated multidimensional eeg characteristics in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: a machine-learning based analysis framework. Sensors 22, 5420 (2022).

Friedman, M. J. Finalizing ptsd in dsm-5: Getting here from there and where to go next. J. Trauma. Stress 26, 548–556 (2013).

Kleijn, W., Hovens, J. & Rodenburg, J. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in refugees: Assessments with the harvard trauma questionnaire and the hopkins symptom checklist-25 in different languages. Psychol. Rep. 88, 527–532 (2001).

Bech, P., Olsen, L. R., Kjoller, M. & Rasmussen, N. K. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the sf-36 mental health subscale and the who-five well-being scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 12, 85–91 (2003).

Kyriazos, T. A. et al. Psychometric evidence of the brief resilience scale (brs) and modeling distinctiveness of resilience from depression and stress. Psychology 9, 1828–1857 (2018).

Ang, K. K., Chin, Z. Y., Zhang, H., Guan, C. Filter bank common spatial pattern (fbcsp) in brain-computer interface. In 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE world Congress on Computational Intelligence), 2390–2397 (IEEE, 2008).

Hlawatsch, F. & Kozek, W. Time-frequency projection filters and time-frequency signal expansions. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 42, 3321–3334 (1994).

Mutanen, T. P. et al. Recovering tms-evoked eeg responses masked by muscle artifacts. Neuroimage 139, 157–166 (2016).

Grobbelaar, M. et al. A survey on denoising techniques of electroencephalogram signals using wavelet transform. Signals 3, 577–586 (2022).

Dem’yanov, V. F., Malozemov, V. N. Introduction to minimax (Courier Corporation, 1990).

Aguiar-Conraria, L. & Soares, M. J. The continuous wavelet transform: Moving beyond uni-and bivariate analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 28, 344–375 (2014).

Kıymık, M. K., Güler, İ, Dizibüyük, A. & Akın, M. Comparison of stft and wavelet transform methods in determining epileptic seizure activity in eeg signals for real-time application. Comput. Biol. Med. 35, 603–616 (2005).

Cohen, M. X. A better way to define and describe morlet wavelets for time-frequency analysis. Neuroimage 199, 81–86 (2019).

Sun, L., Zhao, G., Zheng, Y. & Wu, Z. Spectral-spatial feature tokenization transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–14 (2022).

Yuan, K. et al. Incorporating convolution designs into visual transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 579–588 (2021).

Marin, D. et al. Token pooling in vision transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.03860 (2021).

O’shea, K., Nash, R. An introduction to convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.08458 (2015).

Kavukcuoglu, K. et al. Learning convolutional feature hierarchies for visual recognition. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 23 (2010).

Wang, W., Zhang, K., Su, Y., Wang, J., & Wang, Q. Learning cross-attention discriminators via alternating time–space transformers for visual tracking. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. (2023).

Khodabandelou, G., Chibani, A., Amirat, Y., & Tanimoto, S. A recurrent neural network optimization method for anticipation of hierarchical human activity. IEEE Trans. Automation Sci. Eng. (2023).

Acknowledgements