Abstract

This paper leverages data from February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaras (Turkiye) Earthquake (Mw 7.8) to evaluate seismic risk and assess bridge damage through a fuzzy synthetic approach (FSA). A novel hierarchical damage classification framework is introduced, integrating critical factors such as ground conditions, structural characteristics, and seismic intensity. By analyzing data from 331 bridges affected by eight major historical earthquakes, the study underscored the influence of foundation depth, construction quality, and distance to fault rupture on structural resilience. Notably, 65% of damaged bridges were within 40 km of the distance to fault rupture, with oblique span orientations (45° to 65°) showing heightened susceptibility to seismic forces. To enhance resilience against earthquakes, the findings advocated for the adoption of deep foundations, advanced materials, and optimized structural designs. Consistent with field observations, the study reinforces the utility of FSA in enabling informed decision-making for disaster risk mitigation and is also beneficial for future seismic resilience design of bridges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bridges are an essential component of any highway project that falls under the theme of urban development, but their position in seismically prone regions causes structural damage and economic breakdown. The physical damage to such structures is determined by various elements, including seismic parameters, geotechnical and geological setup, and material characterization1,2. Previous earthquakes in the United States, Taiwan, Japan, Nepal, and Turkiye caused damage to bridges, including both superstructure and substructure, as well as foundations. This resulted in the identification of risk factors, which were then assessed as part of the disaster risk reduction initiative3,4,5. Damage is classified into multiple classes based on the damage pattern caused by ground shaking. Previous researchers offered bridge damage classification using field observations, analytical investigations, and numerical modeling6. A probabilistic approach for measuring bridge resilience that incorporates empirical, analytical, and experimental data is utilized to generate consistent seismic damage limits, which are then confirmed using shaking table tests and calibrated fragility models7,8. Autoregressive models were presented to categorize damage and estimate stiffness in experimental structures by utilizing minimal damage-sensitive characteristics and sensors9,10,11,12,13,14.

Bi and Hao15 conducted a comprehensive numerical analysis using 3D finite element simulations to assess pounding damage and dislocation potentials in a two-span bridge under spatially variable seismic loads, which revealed realistic damage mechanisms. Mangalathu et al.16 proposed a machine learning-based approach for quick post-earthquake damage assessment of bridges, which achieved up to 82% accuracy by taking into account bridge-specific parameters such as span length and reinforcement ratio. Li et al.17 examined seismic damage data from 1069 reinforced concrete girder bridges affected by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake and developed a nonlinear fragility model to measure vulnerability and improve future resilience research. Interlayer area damage model (IADM) with the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method was investigated for efficient seismic damage assessment in a high-speed rail bridge, highlighting the impact of ground motion on damage indices18.

The present study compiles damage data from 331 bridges impacted by 8 well-documented earthquake events (Table 1), aiming to propose a novel damage assessment method for bridges based on reported bridge damage. Details regarding bridge typology, construction materials, and other structural parameters are provided in Table 2. Additionally, risk factors affecting seismic bridge performance were identified, analyzed, and classified within a hierarchical framework. The seismic risk assessment was conducted using a fuzzy synthetic approach (FSA), with the effectiveness of the method demonstrated through February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaras (Turkiye) Earthquake (Mw 7.8) data.

Classification of seismic bridge damages

Bridge damage is determined by the seismic hazard level at the site, which controls the intensity of ground motion. Damage can also result from earthquake-induced ground failures, such as liquefaction, fault displacements, or landslides. As a result, bridge damage classification should include these factors while also taking into account functionality and the level of physical damage, such as fracture dimensions and deformations. Bridge damage (BD) is classified into five categories: none for no visible damage, slight for minor cracking or spalling of structural components, moderate for damage that affects functionality, such as significant cracking, joint failure, or deck displacement, extensive for major cracking, girder damage, or pier dislocation, and collapse for complete structural failure (Table 3).

This newly proposed classification of seismic damage is based on the extent of structural damage to the superstructure and substructure, quantified using specific crack widths (\({w}_{c}\)), crack lengths (\({l}_{c}\)), spalling severity, tilting angle (α), and settlement (\({S}_{s}\)). It integrates damage patterns with traffic functionality, categorizing bridges from “None (VL = very low)” to “Collapse (VH = very high)” based on structural integrity and accessibility. The classification reflects the progressive impact of seismic events on structural performance and operational capacity, aiding in post-earthquake assessments and decision-making for repairs or closures. The limit states are defined using quantitative thresholds for factors given in Table 3, with increasing values representing higher damage levels. System-level performance is set by combining these component limits, where the most critical damage in either the superstructure or substructure dictates the overall bridge functionality.

Primary risk factors for performance assessment

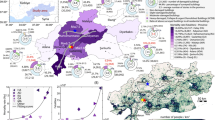

In this study, various data sources were used to identify risk factors influencing bridge seismic performance, including site-specific earthquake damage statistics, structural design reports, and case studies. Tables 1, 2 show the selected earthquake events and data sources for bridge damage. Based on these, Fig. 1 depicts a hierarchical system for assessing seismic risk of bridges.

The primary factors impacting bridge seismic performance are divided into three categories: (1) hazard parameters, (2) structural condition parameters, and (3) ground condition parameters. Each factor is detailed as follows:

Hazard parameters

Intensity levels

Earthquake magnitude, focal depth, and epicentral distance are the most important criteria for bridge engineering. Higher magnitudes, shallow focal depths, and proximity to the distance to fault rupture all contribute to increased seismic activity, increasing the likelihood of bridge damage45,46.

Ground motion parameters

The duration of intense ground motion has a substantial impact on bridge performance, generating cumulative fatigue failure or cracks in structural components. High-frequency ground motion can cause localized spalling or differential displacements in bridge components47,48. Amplification effects may occur if the wavelength of seismic waves coincides with the span of the bridge.

Structural condition parameters

Superstructure and substructure

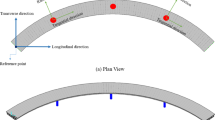

The design and construction of superstructure features like girders and decks has an impact on seismic performance. Inadequate reinforcing and poor construction practices increase vulnerability to lateral stresses. Substructures, such as piers and abutments, exhibit seismic behavior that is determined by their stiffness and foundation depth49,50. Bridges with skewed or curved geometry are more sensitive to seismic forces.

Materials and aging

The seismic capacity of bridge components is greatly influenced by the aging effects and material composition. During seismic occurrences, older bridges with steel reinforcement or deteriorating concrete are more likely to fail. Resilience is enhanced through the use of advanced materials such as fiber-reinforced composites, as noticed in past earthquake scenarios51.

Ground condition parameters

Site geology

Bridges that are located in areas with unfavorable geological conditions, such as fault zones or liquefiable soils, are more vulnerable to foundation failures and differential settlements26. These weaknesses may be made worse by ground instability, which could result in uneven bridge pier support.

Foundation depth and stability

Deeper bridge foundations usually have stronger seismic resilience, but shallow foundations are more vulnerable to damage from increased ground motion. Sediment instability or lateral spreading close to bridge abutments can cause serious structural damage.

Landslides and fault displacements

Bridges on or near unstable slopes are particularly vulnerable to landslides caused by seismic activity. Bridge decking or piers may experience severe structural failure due to sudden, localized deformation brought on by fault movements9,52. By offering a methodical way to assess seismic risk factors for bridges, this hierarchical framework makes it possible to create focused mitigation plans that will increase resilience.

Fuzzy synthetic approach (FSA)

Fuzzy synthetic approach (FSA) serves as a robust decision-making framework that combines fuzzy logic with weighted criteria to analyze and quantify the behavior of complex systems under uncertain conditions. In this study, the methodology follows four principal steps outlined by Tesfamaraim and Saatcioglu53, which are elaborated below:

Identification and prioritization of risk factors

For assessing seismic vulnerability in bridges, a comprehensive set of risk factors (\({R}_{f}\)) is identified and prioritized, as defined by Kir and Yuan54. In Eq. (1), \({R}_{f}\) represents a vector of ten prioritized seismic risk factors defined for assessing bridge vulnerability (refer to Table 4).

The ranking of these factors is linked to damage classification and is determined based on predefined levels: VL (very low), L (low), M (medium), H (high), and VH (very high), as discussed in previous section. This classification assess system-level seismic performance by quantifying component-level damage and integrating it based on bridge typology. For different bridge types (suspension, arch, truss, beam), the importance of components varies. For example, suspension bridges are highly sensitive to cable and anchorage integrity, while arch bridges depend on abutment stability. Factors like foundation depth and adverse geology may be more critical for arch and truss bridges, while traffic load capacity and support systems significantly impact beam bridges. Thus, components carry varying importance depending on structural behavior and seismic vulnerability.

Formation of fuzzy modules

The identified risk factors are standardized through a fuzzification process, where each factor is assigned to memberships corresponding to five defined risk levels. This transformation ensures comparability across parameters. These transformations link to observed bridge damages from eight earthquakes considered in this study (Table 2) by correlating risk factors (e.g., proximity to fault rupture, bridge type etc.) with damage patterns. The fuzzified values represent the degree of association between each factor and damage severity, reflecting how specific conditions influenced superstructure and substructure failures during the studied seismic events. Membership values are determined using a histogram-based method10,55 applied to earthquake damage datasets belonging to February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaras (Turkiye) Earthquake (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5). The derived memberships are detailed in Table 4.

Weight assignment using AHP

The relative significance of each risk factor is represented by a weight set \({W}_{r}\). The analytic hierarchy process (AHP), developed by Saaty56, is employed to calculate these weights through pairwise comparisons of factors. Equation (2) shows the comparison matrix \(\left(\Delta \right)\) which denotes the \(n\times n\) pairwise matrix where each element represents the ratio of seismic risk factors \(\left({R}_{fi}/{R}_{fj}\right)\) for the selected dataset. The widely recognized 1–9 scale57 is utilized in this study due to its ability to maintain the original order consistently, ensure a uniform scaling approach, and enhance perceptual clarity. The details of this scale are presented in Table 5.

The row geometric mean method (RGMM) is utilized to compute the weight of \({R}_{f}\) (\({w}_{ri}\)) and weight set (\({W}_{r})\), according to Crawford and Williams59.

Consistency verification is performed using the geometric consistency index (\(GCI\)) given by Aguarón and Moreno-Jiménez60. In Eq. (5), \(GCI\) measure the consistency of the pairwise comparison matrix (\(\Delta\)) by evaluating the deviations between the matrix ratios (\({d}_{ij}\)) and the corresponding weights (\({w}_{ri}, {w}_{rj}\)).

Thresholds for \(GCI\) are set at 0.31 for \(n\) = 3, 0.35 for \(n\) = 4, and 0.37 for \(n\) > 4. If the \(GCI\) exceeds the threshold, the matrix is adjusted to ensure logical consistency. Final weights are summarized in Table 6.

Unified data architecture

The FSA employs the weighted mean method for aggregating parameters. Fuzzified inputs \(\left({\beta }_{VL},{\beta }_{L},{\beta }_{M},{\beta }_{H},{\beta }_{VH}\right)\) for \(n\) parameters form a fuzzy judgment matrix. The AHP-derived weights are multiplied with this matrix to compute the fuzzy evaluation result.

A fuzzy composite operator “\(\alpha\)” determines the interaction of aggregated factors. Finally, defuzzification translates the fuzzy output into a crisp index (\(I\)) for decision-making61. In Eq. (7), I is calculated by aggregating the weighted contributions (\({{\partial }_{i}\times \beta }_{i}\)) of \(n\) fuzzy risk factors.

This study adopted the weighted average method, assigning equal importance to five-tuple fuzzy sets (\({\partial }_{VL}=0,{\partial }_{L}=0.25,{\partial }_{M}=0.5,{\partial }_{H}=0.75,{\partial }_{VH}=1\)). This approach ensures that all risk factors contribute to the final assessment, preventing data loss.

Case study

On February 6, 2023, a major earthquake (Mw 7.8) devastated southeastern Turkiye and northern Syria, causing significant devastation. This event killed over 50 thousand people, injured thousands, and caused catastrophic infrastructural damage, with over 0.3 million buildings demolished or severely damaged42. The event’s economic toll surpassed $100 billion. The seismic intensity exceeded XI, inflicting significant damage to essential infrastructure, including bridges and transportation networks.

Following the event, a thorough investigation was carried out to assess the damage that 52 bridges, including railroad, pedestrian, and highway structures had incurred. As part of this study, engineering records, design documentation, and maintenance histories were reviewed. A GIS-based database that recorded each bridge’s parameters, including span length, materials, construction type, and comprehensive damage photos, was created in order to arrange the findings. Of the bridges examined, 18 needed immediate repairs because of significant damage, and the remaining bridges showed varied degrees of devastation. In order to anticipate the damage condition of bridges located within 50 km of the distance to fault rupture, FSA was conducted. The results, which were mostly conservative overestimations, showed good agreement with the conditions that were observed.

The analysis of bridge damage reveals that the distance to fault rupture played a significant role in the severity of structural failures. Approximately 65% of damaged bridges were located within 40 km of the distance to fault rupture, with the most severe damage observed within 20 km. For instance, the Elbistan Bridge and Hatay Coastal Bridge, positioned 10 to 15 km from the distance to fault rupture, experienced damage levels of 5 and 4, respectively. Additionally, the orientation of bridge spans relative to fault ruptures influenced damage intensity (Table 7). Bridges oriented at angles of 60° to 90°, such as the Goksun River Bridge (18 km, arch type), sustained the most severe damage. In contrast, bridges oriented parallel to fault lines, such as the Pazarcik Bridge, showed relatively lower damage level of 2 despite similar distance to fault rupture. Bridge-specific variations in damage severity were influenced by factors such as foundation depth, slope conditions, and traffic loads. For example, despite similar distances to fault rupture, the Gaziantep Old Bridge and Reyhanli Bridge displayed damage levels of 3 and 4, respectively, due to differences in support systems and construction quality. Bridges with flexible support systems, shallow foundations, and poor construction quality exhibited heightened vulnerability to seismic forces. The Bahce-Nurdagi Bridge, located within 12 km of the distance to fault rupture, suffered complete collapse due to its shallow foundation and inadequate reinforcement.

The present study FSA demonstrated a closer alignment with observed damage levels compared to62,63 models (refer to Table 7). It accurately predicted 25 out of 33 cases, whereas Nasrollahzadeh’s model correctly estimated 16 cases, and Lin et al.’s model only matched 12 cases. The present study also outperformed other models in capturing extensive (level 4) and collapse (level 5) damage, reducing underestimations seen in previous models. The mismatch between the present study and observed damage primarily arises in cases of higher damage levels (collapse and extensive damage). This discrepancy may result from uncertainties in local geotechnical conditions, structural variations, or simplifications in model assumptions regarding load distribution and material degradation. While the present model reduces underestimation, it occasionally predicts one level lower due to conservatively calibrated parameters.

Nasrollahzadeh’s model frequently underestimated higher damage levels (5 and 4), indicating limitations in its damage amplification mechanism. Lin et al.’s model showed an even stronger underestimation bias, particularly for extensive and collapse damage cases, suggesting it lacks sensitivity to severe structural failures. These models are less capable of handling mismatch due to their lower predictive accuracy in high-damage scenarios. The present study model’s advantage lies in a more refined calibration, enabling better representation of collapse-prone cases.

Figures 6 and 7 highlight the significant impact of the angle between bridge span direction and fault rupture on damage severity. On average, bridges oriented at 45°–65° angles experienced the most damage, with approximately 25 to 30% of the bridges collapsing or suffering extensive damage (red and orange bars). For instance, in subplots (b) and (f), about 20 to 25 bridges recorded moderate to extensive damage at angles of 45°, while fewer than 10 bridges sustained only slight damage. Comparatively, bridges at 15° or 85° angles had lower collapse rates, with slight to moderate damage dominating at an average of 50 to 60% of the total bridges. The data also indicates that the number of bridges with extensive damage (orange bar) peaked for the 45° to 65° angle range across multiple subplots, representing nearly 40% of total damaged structures in certain cases, such as shown in subplots (e) and (h). Conversely, slight damage (green bar) occurred more frequently for angles close to 15° and 85°, accounting for around 60 to 70% of cases. This trend underscores the vulnerability of bridges oriented obliquely (45° to 65°) to fault lines, where seismic forces act more destructively. In contrast, parallel or near-perpendicular orientations exhibit comparatively lower damage intensities, emphasizing the need for optimized span direction in seismic-prone zones. Table 8 summarizes the correlation between different factors and various bridge damage levels:

Effect of the angle between bridge span direction and fault on observed damage levels, examined under: (a) distance to fault rupture; (b) bridge type; (c) support system and (d) construction quality. The data presented here pertains to bridges damaged during the February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaras (Turkiye) Earthquake.

Effect of the angle between bridge span direction and fault on observed damage levels, examined under: (a) adverse geology; (b) foundation depth; (c) slope condition; (d) material type and (e) traffic load capacity. The data presented here pertains to bridges damaged during the February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaras (Turkiye) Earthquake.

The proposed FSA method demonstrated enhanced accuracy by integrating real earthquake damage data, particularly benefiting long-span beam-type bridges (e.g., Adiyaman Bridge: 1800 m) with rigid support and deep foundations. Compared to47,48, which relies on simulated records, the proposed FSA reduced uncertainty, especially for steep-slope structures (e.g., Nurdagi-Gaziantep Bridge). The Scozzese & Minnucci64 approach, which focuses on link slab bridges, is less applicable to the rigid support systems in most Turkish and Nepalese bridges. The Monteiro65 sampling-based method is computationally intensive for multi-span structures (e.g., Tarsus-Adana Bridge: 1600 m), whereas proposed FSA maintained efficiency across varied typologies. Chiu et al.66 consider corrosion effects, yet proposed FSA extended applicability beyond columns to complete structures, improving performance for composite bridges (e.g., Kilis Border Bridge). Monti & Nistico67 scenario-based model evaluated bridge response to specific earthquakes but lacks adaptability for bridges near active faults (e.g., Birecik Bridge: 95 km from rupture). The proposed FSA enhances reliability by considering diverse structural-geotechnical parameters, improving risk assessments across different seismic events.

Conclusions

This study introduces a novel damage classification system for evaluating bridge performance during seismic events, emphasizing the application of the fuzzy synthetic approach (FSA) to enhance the accuracy and reliability of damage assessments. Using data from the Kahramanmaras (Turkiye) earthquake (Mw 7.8), FSA enabled the integration of multiple uncertain and imprecise factors- such as seismic parameters, structural characteristics, and ground conditions, into a comprehensive damage evaluation framework. By incorporating fuzzy logic, the method effectively handled the inherent uncertainties in post-earthquake damage assessment, translating subjective expert judgments and field data into quantifiable damage indices. Key highlights and significant outcomes of this study include:

-

The FSA framework combined with the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) facilitated the prioritization and weighting of ten primary seismic risk factors. This integration allowed for a nuanced evaluation of damage patterns, revealing critical insights into common failure modes, including pier shear and flexural failures, deck displacements, bearing collapses, abutment instabilities, and severe girder cracking.

-

The FSA’s ability to manage vague and complex data proved essential in highlighting the influence of factors like distance to fault rupture, which emerged as a key determinant of damage severity. Moreover, FSA enabled the identification of structural vulnerabilities, such as the increased susceptibility of bridges with flexible supports, shallow foundations, and poor construction quality.

-

The proposed FSA offers a robust, data-driven, and globally adaptable framework that enhances accuracy, reduces subjectivity, and improves reliability in seismic bridge vulnerability assessments compared to existing methodologies62,63.

-

The proposed FSA model showed its enhanced precision, adaptability to various bridge types, which outperform traditional probability-based seismic risk assessment approaches.

Overall, the FSA proved instrumental in synthesizing complex datasets and expert judgments, providing a robust framework for damage assessment. These findings underscore the necessity of integrating fuzzy-based methods in bridge engineering to refine damage evaluations, enhance resilience, and ensure the long-term sustainability of critical infrastructure in seismically active regions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Nasery, M. M., Çelik, M. & Şadoğlu, E. Damage assessment of Siverek Castle during the Kahramanmaraş earthquakes (Mw 7.7 and Mw 7.6) on 06 February 2023: Remediation and strengthening proposals. Eng. Geol. 334, 107511 (2024).

Xia, H. et al. A deep learning application for building damage assessment using ultra-high-resolution remote sensing imagery in Turkey earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 14(6), 947–962 (2023).

Lee, J. H., Ansari, A., An, H. & Jeong, J. Y. Seismic loss and resilience modeling of bridges in soft soils: towards the design of sustainable transportation infrastructure facilities. Sustain. Resil. Infrastruct. 9, 1–23 (2024).

Park, J. & Towashiraporn, P. Rapid seismic damage assessment of railway bridges using the response-surface statistical model. Struct. Saf. 47, 1–12 (2014).

Wang, N., Elgamal, A. & Lu, J. Seismic response of the Eureka channel bridge-foundation system. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 152, 107015 (2022).

Liang, X. Enhancing seismic damage detection and assessment in highway bridge systems: a pattern recognition approach with Bayesian optimization. Sensors 24(2), 611 (2024).

Banerjee, S. & Shinozuka, M. Experimental verification of bridge seismic damage states quantified by calibrating analytical models with empirical field data. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 7, 383–393 (2008).

Zhang, J. et al. Nonlinear seismic response analysis of long-span railway cable-stayed bridges crossing strike-slip faults. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 25479 (2024).

Ansari, A. et al. Robustness assessment of Muscat coastal highway network (CHN) under multi-hazard scenarios focusing on traffic stability and adaptation measures. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 30632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79730-3 (2024).

Ansari, A. et al. Seismic vulnerability assessment and fragility analysis of tunnels in Oman: Development of risk matrices and functionality guidelines. Structures https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.107428 (2024).

Ansari, A., Lee, J. H., Jang, J. G. & Alluqmani, A. E. Seismic microzonation of North Gyeongsang (South Korea) considering liquefaction potential: Application towards seismic risk assessment for Korean nuclear power plants. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 182, 108679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2024.108679 (2024).

de Lautour, O. R. & Omenzetter, P. Damage classification and estimation in experimental structures using time series analysis and pattern recognition. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 24(5), 1556–1569 (2010).

Provost, F. et al. High-resolution co-seismic fault offsets of the 2023 Türkiye earthquake ruptures using satellite imagery. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6834 (2024).

Wang, Q., Liu, K., Wang, M. & Koks, E. E. A river flood and earthquake risk assessment of railway assets along the belt and road. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 12, 553–567 (2021).

Bi, K. & Hao, H. Numerical simulation of pounding damage to bridge structures under spatially varying ground motions. Eng. Struct. 46, 62–76 (2013).

Mangalathu, S., Hwang, S. H., Choi, E. & Jeon, J. S. Rapid seismic damage evaluation of bridge portfolios using machine learning techniques. Eng. Struct. 201, 109785 (2019).

Li, S. Q., Liu, H. B., Farsangi, E. N. & Du, K. Seismic fragility estimation considering field inspection of reinforced concrete girder bridges. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 21, 1–17 (2023).

Duan, H., Jiang, L., Wen, T. & Jiang, L. An improved interlayer area damage model for seismic damage assessment of a high-speed railway long-span arch bridge-track system. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 184, 108811 (2024).

Basöz, N. I., Kiremidjian, A. S., King, S. A. & Law, K. H. Statistical analysis of bridge damage data from the 1994 Northridge, CA, earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 15(1), 25–54 (1999).

Yashinsky, M. Performance of bridge seismic retrofits during Northridge earthquake. J. Bridg. Eng. 3(1), 1–14 (1998).

Kawashima, K. Damage of bridges resulting from fault rupture in the 1999 Kocaeli and Duzce, Turkey earthquakes and the 1999 Chi-Chi, Taiwan earthquake. Struct. Eng. Earthq. Eng. 19(2), 179–197 (2002).

Loh, C. H., Liao, W. I. & Chai, J. F. Effect of near-fault earthquake on bridges: lessons learned from Chi-Chi earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 1, 86–93 (2002).

Maruyama, Y., Yamazaki, F., Mizuno, K., Tsuchiya, Y. & Yogai, H. Fragility curves for expressway embankments based on damage datasets after recent earthquakes in Japan. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 30(11), 1158–1167 (2010).

Tokida, K. I., Oda, K., Nabeshima, Y. & Egawa, Y. Damage level of road infrastructure and road traffic performance in the mid Niigata prefecture earthquake of 2004. Struct. Eng. Earthq. Eng. 24(1), 51s–61s (2007).

Ali, S. M., Khan, A. N., Rahman, S. & Reinhorn, A. M. A survey of damages to bridges in Pakistan after the major earthquake of 8 October 2005. Earthq. Spectra 27(4), 947–970 (2011).

Ansari, A., Rao, K. S., Jain, A. K. & Ansari, A. Deep learning model for predicting tunnel damages and track serviceability under seismic environment. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01556-7 (2023).

Durrani, A. J., Elnashai, A. S., Hashash, Y., Kim, S. J., & Masud, A. The Kashmir earthquake of October 8, 2005: A quick look report. MAE Center CD Release 05–04. (2005).

Han, Q. et al. Seismic damage of highway bridges during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 8(2), 263–273 (2009).

Kawashima, K., Takahashi, Y., Ge, H., Wu, Z. & Zhang, J. Reconnaissance report on damage of bridges in 2008 Wenchuan, China, earthquake. J. Earthq. Eng. 13(7), 965–996 (2009).

Lin, C. C. J., Hung, H. H., Liu, K. Y. & Chai, J. F. Reconnaissance observation on bridge damage caused by the 2008 Wenchuan (China) earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 26(4), 1057–1083 (2010).

Elnashai, A. S., Gencturk, B., Kwon, O. S., Al-Qadi, I. L., Hashash, Y., Roesler, J. R., ... & Valdivia, A. The Maule (Chile) earthquake of February 27, 2010: Consequence assessment and case studies. MAE Center Report No. 10–04. (2010).

Schanack, F., Valdebenito, G. & Alvial, J. Seismic damage to bridges during the 27 February 2010 magnitude 8.8 Chile earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 28(1), 301–315 (2012).

Gautam, D. & Chaulagain, H. Structural performance and associated lessons to be learned from world earthquakes in Nepal after 25 April 2015 (MW 7.8) Gorkha earthquake. Eng. Fail. Anal. 68, 222–243 (2016).

Goda, K. et al. The 2015 Gorkha Nepal earthquake: insights from earthquake damage survey. Front. Built Environ. 1, 8 (2015).

Xie, Q., Gaohu, L., Chen, H., Xu, C. & Feng, B. Seismic damage to road networks subjected to earthquakes in Nepal, 2015. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 16, 649–670 (2017).

Apaydin, N. M. “Earthquake Response of the Transportation Infrastructure in the Region Affected by the February 6 Turkiye Earthquakes’’ Part I-Roads, Railroads and Ports. Journal of Earthquake Engineering. 1-11. (2024).

Apaydin, N. M. & Sikar, R. B. Critical role of the bridges ensuring emergency services and disaster recovery in Turkey. In Bridge Maintenance, Safety, Management, Digitalization and Sustainability (eds Jensen, J. S. et al.) (CRC Press, 2024).

Bayraktar, A. et al. Seismic performance of bridge expansion joints with and without viscous dampers during the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes. Buildings 14(8), 2538 (2024).

Bayraktar, A., Ventura, C. E., Yang, T. Y., Hökelekli, E. & Taş, Y. Observed Damage Behavior of Earth Dams During the 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Turkey, Earthquakes. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 42, 1–16 (2024).

Caner, A., Cinar, M. & Ates, A. D. Observed seismic performance of buildings and bridges during a major earthquake followed by one other major earthquake in the close vicinity of the first one. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 23, 1–24 (2024).

Ozkaynak, M. I. & Cetin, K. O. The performance of Karasu Bridge following the February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaras-Turkiye earthquake sequence. Eng. Geol. 335, 107512 (2024).

Ozkula, G. et al. Field reconnaissance and observations from the February 6, 2023, Turkey earthquake sequence. Nat. Hazards 119(1), 663–700 (2023).

Shirato, M. & Odawara, Y. Field observations on the damage to road bridges after the 2023 Turkey earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 40(2), 997–1018 (2024).

Tobita, T., Kiyota, T., Torisu, S., Cinicioglu, O., Tonuk, G., Milev, N., ... & Shiga, M. (2024). Geotechnical damage survey report on February 6, 2023 Turkey-Syria Earthquake, Turkey. Soils and Foundations, 64(3), 101463.

Capacci, L., Biondini, F. & Frangopol, D. M. Resilience of aging structures and infrastructure systems with emphasis on seismic resilience of bridges and road networks. Resil. Cities Struct. 1(2), 23–41 (2022).

Rahman, A. U. et al. An updated earthquake catalogue and source model for seismic hazard analysis of Pakistan. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 5219–5241 (2021).

Ozsarac, V., Monteiro, R. & Calvi, G. M. Probabilistic seismic assessment of reinforced concrete bridges using simulated records. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 19(4), 554–574 (2023).

Ozsarac, V., Monteiro, R., Askan, A. & Calvi, G. M. Impact of local site effects on seismic risk assessment of reinforced concrete bridges. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 164, 107624 (2023).

Mwafy, A., Kwon, O. S. & Elnashai, A. Seismic assessment of an existing non-seismically designed major bridge-abutment–foundation system. Eng. Struct. 32(8), 2192–2209 (2010).

Wang, W. & Su, C. Automatic classification of reinforced concrete bridge defects using the hybrid network. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47(4), 5187–5197 (2022).

Zhao, D., Chen, B. & Sun, J. Enhancing performance of engineering structures under dynamic disasters with ECC–FRP composites: A review at material and member levels. Buildings 13(8), 2099 (2023).

Prendergast, L. J. et al. Structural health monitoring for performance assessment of bridges under flooding and seismic actions. Struct. Eng. Int. 28(3), 296–307 (2018).

Tesfamaraim, S. & Saatcioglu, M. Seismic risk assessment of RC buildings using fuzzy synthetic evaluation. J. Earthq. Eng. 12(7), 1157–1184 (2008).

Kir, G. J. & Yuan, B. Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic—Theory and Applications (Prentice-Hall, 1995).

Medasani, S., Kim, J. & Krishnapuram, R. An overview of membership function generation techniques for pattern recognition. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 19(3–4), 391–417 (1998).

Saaty, T. L. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP). J. Oper. Res. Soc. 41(11), 1073–1076 (1980).

Power, M. S., Rosidi, D., & Kaneshiro, J. Y. Seismic vulnerability of tunnels and underground structures revisited. In North American Tunneling’98American Underground Construction Association. (1998).

Saaty, T. L. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J. Math. Psychol. 1, 57–68 (1977).

Crawford, G. & Williams, C. A note on the analysis of subjective judgment matrices. J. Math. Psychol. 29(4), 387–405 (1985).

Aguarón, J. & Moreno-Jiménez, J. M. The geometric consistency index: Approximated thresholds. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 147(1), 137–145 (2003).

Sadiq, R., Husain, T., Veitch, B. & Bose, N. Risk-based decision-making for drilling waste discharges using a fuzzy synthetic evaluation technique. Ocean Eng. 31(16), 1929–1953 (2004).

Kiani, H. & Nasrollahzadeh, K. Fuzzy logic approach for seismic fragility analysis of RC frames with applications to earthquake-induced damage and construction quality. Structures 55, 1122–1143 (2023).

Lin, J. W. Fuzzy regression decision systems for assessment of the potential vulnerability of bridge to earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 64, 211–221 (2012).

Scozzese, F. & Minnucci, L. Seismic risk analysis of existing link slab bridges using novel fragility functions. Appl. Sci. 14(1), 112 (2023).

Monteiro, R. Sampling based numerical seismic assessment of continuous span RC bridges. Eng. Struct. 118, 407–420 (2016).

Chiu, C. K., Lyu, Y. C. & Jean, W. Y. Probability-based damage assessment for reinforced concrete bridge columns considering the corrosive and seismic hazards in Taiwan. Nat. Hazards 71, 2143–2164 (2014).

Monti, G. & Nistico, N. Simple probability-based assessment of bridges under scenario earthquakes. J. Bridg. Eng. 7(2), 104–114 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-CRP-2025-2225”.

Funding

This research was supported and funded by the Sultan Qaboos University research funds (DVC/EMC/24).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. A.E.A. Z.H. J.H.L. G.O: Main author, conceptualization, literature review, manuscript preparation, application of fuzzy models, methodological development, statistical analysis, detailing, and overall analysis; Y.F. T.S. and A.A.: Data compilation, data analysis, comprehensive analysis, detailed review, and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari, A., Alluqmani, A.E., Huang, Z. et al. Fuzzy synthetic approach for seismic risk assessment of bridges with insights from the 2023 Kahramanmaras Earthquake in Turkiye. Sci Rep 15, 13418 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98277-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98277-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Yielding brace system as a next-generation lateral load mechanism for seismic resilient cities

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Integrated GIS-AHP based assessment of earthquake vulnerability and risk for urban residential buildings in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Diffusion-based generative AI framework for long-term degradation forecasting and risk assessment of steel fibre reinforced fly ash-based concrete

Discover Computing (2025)