Abstract

Dual-task composed of gait or stepping tasks combined with cognitive tasks has been well-established as valuable tools for detecting neurocognitive disorders such as mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. We previously developed a novel dual-task system with high accuracy for differentiating patients with neurocognitive disorders from healthy controls. In this study, we aimed to elucidate whether the output value obtained through artificial intelligence assumptions has clinical meaning other than diagnosis labelling. This is a retrospective cross-sectional study. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, or mild cognitive impairment who participated in our previous dual-task experiment and completed all routine neuropsychological assessments at our hospital within one year of the experimental date were eligible for inclusion in the neurocognitive disorders group. Participants in the healthy control group were recruited from community-dwelling older adults. The correlation between the output value, “y-value”, and each neuropsychological test: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Addenbrook’s Cognitive Examination, Logical Memory tests, Frontal Assessment Battery, and digit span were assessed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. We also evaluated the correlation between the MMSE and those neurocognitive tests. To elucidate the diagnostic availability of the dual-task system and the MMSE on this dataset, we conducted a receiver operating characteristic analysis. We enrolled 97 participants in the neurocognitive disorders group: 42 with Alzheimer’s disease dementia, 11 with dementia with Lewy bodies, and 44 with mild cognitive impairment. Additionally, 249 participants were included in the healthy control group. Although the y-value showed significant correlations with several tests, the MMSE demonstrated much stronger significant correlations with a broader range of cognitive tests. Meanwhile, its sensitivity and specificity were 0.969 and 0.912, respectively, and the area under the curve was 0.981, which was higher than the 0.934 of the MMSE. Our new AI-driven dual-task system has a high ability to predict neurocognitive disorders. However, the clinical significance of its output values is limited to screening for neurocognitive disorders and does not extend to estimating cognitive function. When using this system in clinical practice, it is essential to understand its limitations and select the appropriate usage scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The predictive efficacy of a dual-task approach for Alzheimer’s disease dementia (ADD), the most common cause of dementia with few prominent neurological symptoms, has been well recognised since the 1990s1. Gait disturbances can result from various physical issues, including orthopaedic conditions such as osteoarthritis and skeletal deformities, as well as neurological conditions such as sensory ataxia, parkinsonism, and paralysis2. Gait abnormalities, in contrast, are less frequently associated with ADD3. Gait is associated with executive function and attention, both of which share the capacity of the frontal lobes, especially the prefrontal areas4. This approach has been identified as a valuable tool for predicting the progression of cognitive impairment5, assisting in the differential diagnosis of diverse gait disturbances6, and facilitating cognitive stimulation7.

Early detection of neurocognitive disorders is critical for providing patients with advanced care planning and early intervention opportunities8. As expensive disease-modifying therapies continue to be developed, it is essential to efficiently exclude healthy individuals from further intervention9. However, misdiagnosis of dementia is common in primary care settings10, emphasising the need for an easily administered tool that exhibits low variability among testers, requires no specialist knowledge, and ensures high accuracy.

To address this need, we developed a dual-task system incorporating a deep learning model that integrates cognitive test data and stepping motion analysis11. The system requires participants to step while completing cognitive tasks using handrails to ensure safety and space efficiency. A novel technique, the phase-aligned periodic graph convolutional network (PPGCN), was introduced to recognise stepping motions and process periodic graph information to improve diagnostic accuracy. We trained a deep-learning system to develop a reliable diagnostic tool for screening neurocognitive disorders (NCD). In our dataset, the system achieved a high accuracy of 0.966 in differentiating healthy older adults from individuals with ADD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Although this level of accuracy suggests significant clinical utility, the interpretability of deep learning systems in medical practice remains a critical concern, as the clinical significance of their output is often unclear. In our dual-task system, we have the output continuous value, "y-value", for each user to predict the diagnostic classification. However, the internal process of deep learning is like a black box, and the clinical interpretation of y-values other than diagnostic prediction remains elusive.

In this observational, cross-sectional study, we aimed to elucidate the clinical significance of the novel dual-task diagnostic system using the PPGCN by investigating the associations between the system’s output (y-values) and the Mini-Mental State Examination-Japanese (MMSE-J)12, which is the most widely used screening test for neurocognitive disorders in clinical practice, as well as various other neuropsychological test data collected at our hospital. We hypothesised that the output of a dual-task system is associated with specific neurocognitive domains. Additionally, we compared the diagnostic capabilities of the dual-task system and the MMSE-J on the same dataset to explore the potential of this dual-task system in clinical practice.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled participants with dementia or MCI who participated in our previous dual-task experiment from November 2021 to January 202411. These individuals had undergone routine neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessments at the Department of Psychiatry at Osaka University Hospital within one year from the date of the patient’s visit. The eligibility criteria in the previous study were as follows: (1) those diagnosed with ADD, DLB, or MCI according to international criteria13,14,15; (2) those without uncontrolled physical illness or psychiatric disorders; and (3) those whose doctors had judged that their participation in the study could be harmful to their mental or physical health. This was defined as the neurocognitive disorders (NCD) group. Regarding healthy controls (HC), a company recruited participants from community-dwelling older individuals. The requirements were as follows: (1) aged 70–90 years and (2) able to use smartphones or tablets. Of the recruited older individuals, we selected participants in the HC group who met the following criteria: (1) scored 28 or higher on the MMSE and (2) subjectively reported to be perfect in self-reported activities of daily living. We did not exclude participants with gait disorders or other physical problems affecting stepping and arithmetic tasks unless they could not conduct the tasks. This was because our system was thought to be able to remove those effects by learning the data of both dual-task and single-task. They conducted the dual-task experiment from 2021 to 2023. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Osaka University Hospital (Identification No. 21236 [T9]) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research of Osaka University (Approval Number: R6-01). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their information was anonymised before analysis. All the procedures contributing to this work complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The dual-task system

Although the details of the development of this dual-task system are reported in our previous study11, we shall also explain it briefly in this section.

This study utilised a Dual-task system (Fig. 1) comprising a Microsoft Kinect V2 (camera), a stand for the camera, a personal computer, a display screen, a stand for the display, a quick-response (QR) code reader, handrails, and response buttons. The participants were instructed to step in the middle of the handrails while simultaneously answering questions displayed on the front screen using answer buttons. Following the instructions displayed on the screen, participants logged in using a pre-prepared QR code and then proceeded to five measurement sessions (two practice sessions and three main sessions) that comprised the entire dual-task process. The practice sessions aimed to minimise the influence of non-cognitive factors, such as unfamiliarity with the system. The main sessions aimed to evaluate each participant based on statistical features to reduce bias. Before the measurement, we explained the details of the dual-task process to each participant and ensured that they understood the purpose of the test.

Dual task system. The participants were instructed to step in the middle of the handrails while simultaneously answering questions displayed on the front screen using the answer buttons. The system consists of a Microsoft Kinect V2 (camera), a camera stand, a personal computer, a display screen, a display stand, a QR code reader, handrails, and response buttons.

Each practice session consisted of a 20-s single-task, where the participant answered arithmetic questions, followed by a 10-s stepping task, and concluded with a 20-s dual-task, in which the participant steps repeatedly while answering arithmetic questions. In each main session, the order of the tasks remained the same as that in the practice trial, but the durations were extended to 30 s for the arithmetic task, 20 s for the stepping task, and 30 s for the dual-task. The arithmetic task comprised two-choice questions asking participants to add or subtract a one-digit number and a two-digit number smaller than 20, generated randomly to avoid the practice effect.

This system used three neural networks: Pose Network (PPGCN), Cog Network and Fusion Network. As to Pose Network, the video in the stepping tasks was interpolated to 10 frames per second, and the positions of the 17 joints were quantified in 2 dimensions. For single stepping, the 10 s from 7 to 16 s were used, and for dual stepping, the 20 s from 7 to 26 s were used, and the final input for a participant was three matrixes of (300 × 17 × 2) with three trials of 300 frames × 17 joints × 2 dimensions. For Cog Network, we logged four data sets, including the average response time and accuracy in arithmetic task trials for both single- and dual-task. These formed the number of trials × 4-shaped inputs to the network. Finally, the outputs from the Pose Network and Cog Network were input into the Fusion Network to calculate the ‘y-value’.

The y-value represents the output of our system. In our approach, we combined both cognitive and stepping features, which were then fed into a fusion network consisting of a batch normalization layer followed by a series of fully connected layers. Finally, we applied a sigmoid function to transform the output from the last fully connected layer into a predicted probability (y-value), representing the likelihood that an input sample is positive (i.e., indicative of MCI or dementia). The y-value lies within the range [0, 1], and was calculated by defining a loss function that takes into account the discrimination of two-class classification problems. Note that It does not represent the severity of dementia. During the model training, the cutoff value for the y-value was set to 0.5 for the two-class classification of NCD and HC, based solely on the training data (dual-task data paired with the final diagnosis result). In this study, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was carried out, and a cutoff value based on the Youden index was adopted, aiming at obtaining a more reasonable cutoff value not only based on the training dual-task data, but also the whole dataset with various clinic criteria. Note that in this study, we treated sensitivity and specificity as equally important. However, the cutoff value of our dual-task model can be adjusted for different applications by altering the weight given to sensitivity or specificity. For instance, when optimizing the cutoff to identify more potential dementia or MCI candidates—typically required in automatic pre-screening systems—we can assign greater importance to sensitivity. On the other hand, in a clinical setting, we may prioritize specificity to ensure more accurate diagnoses.

Data collection

In the dual-task experiment, each participant was given a y-value produced through deep learning that could be used for differential diagnosis. In this study, we extracted the clinical data of all participants from the hospital’s electronic health records. The patients visiting our clinic were routinely assessed for demographic data, medical history, neurological examinations, standard neuropsychological examinations, routine laboratory tests, and brain neuroimaging findings. General cognition was assessed using the MMSE and Addenbrook’s Cognitive Examination, third edition (ACE-III). Memory was assessed using the Logical Memory (LM) subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R), consisting of immediate recall (LM-I) and delayed recall (LM-II). Frontal function was evaluated using the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) and the digit span subtest of Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test -Fourth edition (WAIS-IV). Dementia severity was assessed using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). These assessments were conducted by neuropsychiatrists and clinical psychologists specialising in geriatric psychiatry. Clinical assessments were imperfectly followed up on an annual basis for each patient. In this study, we used the neuropsychological assessment data closest to the date of the dual-task experiment, provided it was obtained within one year.

Statistical analyses

We described the demographic data and y-values for each diagnosis and compared them between the dementia plus MCI group (NCD group) and the HC group. Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to investigate the association of each neuropsychological test, age, and Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes (CDR-SB) with the y-value and MMSE-J score. Correlation strength was categorised as follows: < 0.3 as “poor,” < 0.6 as “fair,” < 0.8 as “moderately strong,” and < 1.0 as “very strong”16. To elucidate the diagnostic availability of the dual-task system and MMSE-J on the same dataset, we conducted logistic regression analysis with the covariates of age, sex and MMSE-J, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. All statistical analyses adopted a two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 to indicate statistical significance. These analyses were performed using JMP Pro 17.2.0. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participants’ demographics

Of the 108 patients who performed the dual task during the study period, we selected 97 participants in the NCD group with complete records of neuropsychological assessments within one year from the date of the experiment. There were 42, 11, and 44 diagnoses of ADD, DLB, and MCI, respectively. A total of 249 HC were recruited. Age and MMSE-J scores differed significantly between the two groups. The mean y-values (standard deviation: SD) were 0.947 (0.098) in ADD, 0.927 (0.105) in DLB, 0.823 (0.254) in MCI, 0.89 (0.19) in the NCD group, and 0.11 (0.20) in the HC group. Significant differences were observed between NCD and HC groups (Table 1). The results of neuropsychological tests are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

The correlation between y-value, MMSE-J, and other neuropsychological tests

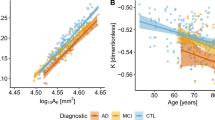

Table 2 shows the results of Pearson’s correlation coefficients. A significantly poor negative correlation was observed between the y-value and MMSE-J score (r = -0.263). The Y-value showed weak negative correlations with neuropsychological tests, including the FAB (r = -0.263), the ACE-III total score (r = -0.267), sub-scores for attention (r = -0.265) and visuospatial (r = -0.237), as well as immediate (LM-I; r = -0.229) and delayed recall (LM-II; r = -0.229) from the WMS-R. A fair correlation was observed only with the CDR-SB (r = 0.308). No significant correlations were found with the memory, fluency, and language subscores of the ACE-III or with age groups. MMSE-J demonstrated very strong correlations with ACE-III total score (r = 0.843) and attention sub-score (r = 0.809), moderately strong correlations with ACE-III memory (r = 0.750), fluency (r = 0.639), WMS-R LM I (r = 0.609), and CDR-SB (r = 0.766), as well as fair correlations with FAB (r = 0.555), ACE-III language (r = 0.493) and visuospatial (r = 0.422) sub-scores, WMS-R LM II (r = 0.471), and WAIS-IV digit span (r = 0.531). No significant correlation was observed between the MMSE-J and age.

The diagnostic availability of y-value

The logistic regression analysis failed because of the high multicollinearity of the independent factors. ROC analysis identified Youden-derived cut-off points, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for distinguishing between NCD and HC. In that order, these were 0.397, 0.969, 0.912, 0.825, and 0.987 for the y-value, and 27, 0.845, 1, 1, and 0.943 for the MMSE. A y-value of 0.397 or lower and an MMSE score of 27 or lower most accurately predicted NCD. The areas under the curve (AUCs) were 0.981 for the y-value and 0.934 for the MMSE. The ROC curves are shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between the y-value from our dual-task diagnostic system and various clinical measures, including neurocognitive test results and diagnoses, and compared these with the MMSE-J associations. Although the diagnostic accuracy of the y-value from the dual-task system was superior to that of the MMSE-J, the correlations between cognitive tests and dementia severity scales were stronger for the MMSE-J than for the y-value.

The y-value showed significant correlations between the MMSE-J, FAB, ACE-III total scores, attention and visuospatial subtests, WMS-R LM I and II, and CDR-SB scores. Zhou et al. found that the dual-task performance, involving gait and numerical subtraction, correlated with global cognition, processing speed, and working memory but not with episodic memory, flexibility, or reasoning17. Their correlation coefficients of -0.27 for global cognition and -0.22 for processing speed were similar to the correlations observed in our study. Other studies, such as that by Cristina Åberg et al., used the Timed Up and Go test with verbal fluency and reverse reciting for months18, whereas Montero-Odasso et al. used gait velocity in combination with tasks such as reverse counting, subtraction, and verbal fluency5. As the cognitive tasks used in the studies were different, it is necessary to be aware of the possibility that related cognitive functions may also differ. In our system, stepping image recognition was combined with calculations displayed on a front-facing monitor, and we hypothesised that executive functions, attention, digit span, and visuospatial functions would show stronger correlations because of their roles in motor control4, calculation, and recognition of visual tasks. While the ACE-III subtests partially supported this assumption, the differences in correlation coefficients were smaller than those reported by Zhou et al., and no significant correlation was observed between our system’s y-value and the digit span task from the WAIS-IV, which assesses attention and working memory. The correlations between the MMSE-J and other cognitive tests were notably stronger than those between the y-values and cognitive assessments. This suggests that an AI-driven dual-task model trained with a diagnostic outcome as the target may be less effective than the MMSE-J in assessing specific cognitive impairments. We trained the model with diagnoses of the samples, prioritizing diagnostic accuracy because we intended to use this system as a screening tool. If we train the model with the severity of cognitive impairments, the output value will probably be more correlated with cognitive impairments but less correlated with diagnoses.

Our dual-task system showed high potential for differentiating patients with dementia and MCI from HC. The system’s sensitivity and specificity were 0.969 and 0.912, respectively, which are consistent with the values reported in our previous study11. The AUC value was higher than that of the MMSE-J. However, to generalise these results to a broader clinical population, we must address the limitation that the HC group was selected based on MMSE-J scores > 27. As a result, the distribution of MMSE-J scores for healthy people was skewed, and the cutoff for the MMSE-J was more likely to be 27/28.

Therefore, caution is needed when interpreting the comparison between y-values and MMSE scores. Due to the study design, the participants were not directly assessed by physicians using imaging tests, which limited our ability to safely exclude individuals suspected of having neurocognitive disorders. To use this system as a screening tool for early-stage neurocognitive disorders, we applied strict inclusion criteria to the HC group. The original cutoff score for MCI and healthy people on the MMSE-J was 27/2819, which is consistent with the results of this study.

Regarding the diagnostic differences between ADD and DLB, the mean y-value was lower in the MCI group than in either dementia group, which is consistent with MCI’s intermediate position between a healthy state and dementia in the neurodegenerative continuum20. Notably, the mean y-value was lower in the DLB group than in the ADD group. Participants in the DLB group were older than those in the ADD group, and DLB was typically associated with more severe attentional deficits, visuospatial deficits, and motor dysfunction than was ADD21. Hence, it was assumed that the performance of the DLB group would be worse than that of the ADD group. Contrary to this assumption, the opposite was observed. These findings suggest that the dual-task system can predict diagnostic outcomes beyond simple task performance, which may explain its weaker association with specific cognitive tests.

The great strength of the deep learning, which has been trained on both dual-task and single-task data, is that it can reduce the influences of the various factors that must be taken into account when interpreting the results of single tasks. This ability could be crucial for screening the general population, especially given the prevalence of physical impairments related to monitoring visual cues, listening to instructions, and stepping, as well as inconsistencies in tester skill levels. Unlike formal cognitive functional assessment scales like MMSE, it also has the potential to alleviate the psychological burden associated with cognitive testing. We assume this system will be useful in general practitioner clinics and community settings for screening MCI and early-stage dementia, especially where there is a lack of human resources to conduct and interpret screening cognitive tests like MMSE.

Limitation

This study has several limitations in addition to the selection bias mentioned in the Discussion section. First, the data for participants in the NCD and HC groups were collected from different facilities. Although the procedure and setting were standardised, and we confirmed consistency in differential diagnosis using data from HC who performed the dual-task at Osaka University Hospital, where patients with NCD were also assessed, all experiments were conducted by staff from SANKEN. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the system performs similarly if used by different testers at different sites. Second, not all types of dementia or MCI, such as those involving cerebrovascular cognitive deficits, were included. We assumed that such cases are typically identified by caregivers and physicians based on the stroke history; therefore, they were excluded from this study. Third, due to the lack of patients, particularly DLB patients, we were unable to create a model to identify subgroups of NCDs. We hope to improve the model by increasing the number of cases in the future and tackle this issue again. Fourth, the diagnosis of NCD was not based on biomarkers. The diagnosis of AD is shifting to a biomarker-based approach, such as amyloid positron emission tomography and cerebrospinal fluid testing22. Plasma tests for amyloid-β and tau are also currently available for research purposes23, but they are not yet widely accessible in clinical settings. As biomarker-based diagnostics become more widely adopted, modifications to our dual-task system may be necessary to integrate these advancements. Finally, we adopted the p-value of 0.05 as a statistically significant threshold at the correlation analysis without any corrections for multiple comparisons. The p-values for the correlation between the y-values and the cognitive tests in this analysis are relatively high, and it is necessary to consider the possibility that there is actually no correlation. However, we do not believe that this is contrary to the points made in the article.

Conclusions

This study retrospectively investigated the association between the predictive value of our dual-task system and cognitive deficits in patients with dementia and MCI, as well as its diagnostic capacity in distinguishing these patients from HC. Although our novel dual-task system demonstrated a high performance in predicting diagnoses, the associations between its predictive value and several cognitive tasks were weaker than those observed using the MMSE-J. This study highlights that the diagnosis-predictive value produced by the deep learning model trained by diagnoses in the dual-task system is useful for screening NCDs but less effective for comprehensive assessments of neurocognitive deficits. Based on these results, this system could become a clinically useful screening tool when applied in appropriate contexts.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE-III:

-

Addenbrook’s Cognitive Examination, third edition

- ADD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease dementia

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CDR:

-

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CDR-SB:

-

CDR sum of boxes

- DLB:

-

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- FAB:

-

Frontal Assessment Battery

- HC:

-

Healthy controls

- LM:

-

Logical Memory

- WAIS-IV:

-

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test fourth edition

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE-J:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination-Japanese

- NCD:

-

Neurocognitive disorders

- PPGCN:

-

Phase-aligned periodic graph convolutional network

- QR:

-

Quick-response

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- WMS-R:

-

Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised

References

Camicioli, R., Howieson, D., Lehman, S. & Kaye, J. Talking while walking. Neurology 48, 955–958. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.48.4.955 (1997).

Pirker, W. & Katzenschlager, R. Gait disorders in adults and the elderly. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 129, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-016-1096-4 (2017).

Verghese, J. et al. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer’s dementia. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1761–1768. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020441 (2002).

Yogev-Seligmann, G., Hausdorff, J. M. & Giladi, N. The role of executive function and attention in gait. Mov. Disord. 23, 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21720 (2008).

Montero-Odasso, M. M. et al. Association of dual-task gait with incident dementia in mild cognitive impairment: Results from the gait and brain study. JAMA Neurol. 74, 857. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0643 (2017).

Auvinet, B., Touzard, C., Montestruc, F., Delafond, A. & Goeb, V. Gait disorders in the elderly and dual task gait analysis: A new approach for identifying motor phenotypes. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0218-1 (2017).

Jardim, N. Y. V. et al. Dual-task exercise to improve cognition and functional capacity of healthy older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 589299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.589299 (2021).

Porsteinsson, A. P., Isaacson, R. S., Knox, S., Sabbagh, M. N. & Rubino, I. Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical practice in 2021. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2021.23 (2021).

Jönsson, L. et al. The affordability of lecanemab, an amyloid-targeting therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: An EADC-EC viewpoint. Lancet Reg Health - Eur. 29, 100657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100657 (2023).

Bradford, A., Kunik, M. E., Schulz, P., Williams, S. P. & Singh, H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 23, 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc (2009).

Godó, Á. et al. PPGCN: Phase-aligned periodic graph convolutional network for dual-task-based cognitive impairment detection. IEEE Access 12, 37679–37691. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3371517 (2024).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. Mini-mental state. J.Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 (1975).

McKhann, G. M. et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 (2011).

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies. 89:88-100. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55948-1_5 (2017).

Albert, M. S. et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 (2011).

Chan, Y. H. Biostatistics 104: Correlational analysis. Singapore Med. J. 44, 614–619 (2003).

Zhou, J. et al. The age-related contribution of cognitive function to dual-task gait in middle-aged adults in Spain: Observations from a population-based study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4, e98-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00009-0 (2023).

Åhman, H. B. et al. Dual-task tests discriminate between dementia, mild cognitive impairment, subjective cognitive impairment, and healthy controls—A cross-sectional cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 20, 258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01645-1 (2020).

Sugishita, M. et al. The validity and reliability of the japanese version of the mini-mental state examination (MMSE-J) with the original procedure of the Attention and Calculation Task (2001). Jpn. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 91–110. https://doi.org/10.11253/ninchishinkeikagaku.20.91 (2018).

Jack, C. R. et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 12, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0 (2013).

Noe, E. et al. Comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies to Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Mov. Disord. 19, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.10633 (2004).

Jack, C. R. et al. NIA-AA research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 535–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 (2018).

Blennow, K. & Zetterberg, H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: Current status and prospects for the future. J Intern Med. 284, 643–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12816 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the contributions of all participants and staff from SANKEN and the Department of Psychiatry, Osaka University. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant JP24uk1024001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS designed the study. YS and SW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SW, DT, SS, YS, MS, and MI collected experimental and clinical data. AG, SW, FO, and YY developed the dual-task system. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Osaka University Hospital (Identification No. 21236 [T9]) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research of Osaka University (Approval Number: R6-01). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and their information was anonymised before analysis. All the procedures contributing to this work complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Satake, Y., Taomoto, D., Wu, S. et al. The clinical significance of an AI-based assumption model for neurocognitive diseases using a novel dual-task system. Sci Rep 15, 13989 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98319-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98319-y