Abstract

Volcanic tuffs are abundant in several regions of the world, and their use has emerged as an economically viable alternative for geopolymer production. This study investigates the effects of incorporating 0 to 30% blast furnace slag (BFS) into volcanic tuff (VT)-based geopolymer mortars cured at room temperature and 80 °C on various properties, including setting time, mechanical strength (compressive and flexural), workability, water absorption and microstructure. Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to characterize the geopolymer mortars. Sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate are used as alkaline activators. Results revealed that pure VT pastes exhibited exceptionally long setting times, approximately 48 h. However, replacing 10% of VT with Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) reduced this to 435 min. The effect of BFS on compressive strength was time-sensitive. At 7 days, a substantial increase from 2.42 MPa to 9.03 MPa was observed with 30% BFS incorporation. Conversely, under ambient curing, 28-day strength decreased. However, curing at 80 °C for 48 h improved 28-day strength to 15.03 MPa with 30% BFS. Furthermore, results revealed that incorporating 30% BFS significantly enhanced workability, resulting in a 92.08% reduction in flow time. Absorption water and Microstructural analysis confirmed a strong correlation between the degree of geopolymerization and mechanical performance. These findings highlight BFS as a promising additive for optimizing VT-based geopolymer mortars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alkali-activated materials (AAMs) are a class of advanced binders synthesized by the chemical activation of alumina and silicate precursors by strongly alkaline solutions1. These precursors, may be of natural origin (natural pozzolan (NP), volcanic tuff (VT), clay) or industrial by-products (fly ash (FA), Blast furnace slag (BFS))2,3, undergo a dissolution-precipitation mechanism that facilitates the formation of complex aluminosilicate gel structures4. The chemical reactions, predominantly occurring at relatively low temperatures (25–100 °C), lead to the generation of geopolymeric matrices, which exhibit superior mechanical properties and enhanced durability when compared to conventional binders. AAMs have garnered significant attention recently due to their favorable technical properties and environmental benefits. These materials are seen as promising alternatives to Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), as they offer substantial reductions in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with the cement production process. The production of AAMs does not require the energy-intensive clinkerization stage typical of OPC, which occurs at temperatures of 1350–1450 °C. Instead, AAM production can be carried out at lower temperatures, leading to reductions in energy consumption and CO2 emissions of up to 70% 5, a critical factor in mitigating the environmental footprint of the construction sector, which currently accounts for around 7% of global CO2 emissions6,7. One of the primary challenges in the development of AAMs lies in the variability of the chemical and mineralogical compositions of the precursors, particularly industrial by-products such as FA and BFS. This variability complicates the optimization and standardization of alkaline activation processes, which are crucial for tailoring the mechanical performance and durability of AAMs. Global availability of FA and BFS is also limited, with current annual production estimated at 777 Mt for FA and 300–360 Mt for BFS8. In contrast, global OPC production exceeds 4.1 billion tons per year9, highlighting the need for alternative materials that can supplement or replace traditional cementitious binders on a large scale. To overcome these material supply constraints, new formulations such as Alkali-Activated Binary Cements (AABCs) and Hybrid Cements (HCs) have been introduced. AABCs are produced by combining two distinct precursors, while HCs integrate OPC with AAC technology, leveraging the synergistic effects of both systems. These innovations allow for the production of cement with a high aluminosilicate content (up to 70%) and a reduced OPC content (approximately 30%), resulting in materials that not only meet performance standards but also offer significant environmental advantages10,11. In terms of industrial adaptability, the use of volcanic tuff has emerged as a commercially viable alternative for MAA production. VTs are abundant in many parts of the world, particularly in tropical areas, and offer a stable source of high-quality raw materials2,12. It is important to note that the processing of MAA derived from VTs requires less energy than that of OPCs, as calcination of the raw materials is not always necessary13. Nevertheless, in some cases, heat treatment can still be applied to improve VT reactivity, particularly when the material has semi-crystalline characteristics or lacks sufficient reactive components such as CaO and Al2O3 14,15.

Ilker Tekin16 observed that thermal curing primarily enhanced the early-age strength of geopolymer pastes composed of 80% volcanic tuff and 20% marble or travertine waste. For instance, he recorded a compressive strength of approximately 36 MPa on the second day under 75 °C, whereas the strength reached 46 MPa after 90 days at ambient temperature. Similarly, Kantarci Fatih et al.17 investigated the effects of curing temperature and activator characteristics (type and concentration) on the microstructure and mechanical properties of volcanic tuff-based geopolymer mortars and concretes. Their findings revealed that the compressive strength of geopolymer specimens increased with NaOH concentration, achieving a peak value of 37.9 MPa after 90 days when cured at 120 °C for 72 h. Conversely, Barıs et al.18 reported that a geopolymer derived from Datça tuff, cured at 90 °C for 24 h, exhibited a compressive strength of 10.5 MPa when the KOH concentration was increased from 7.5 M to 12.5 M, followed by a subsequent decline.

Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of improving AAM performance by incorporating supplementary cementitious materials such as BFS and MK. These additions serve as secondary sources of reactive CaO and Al2O3, which can further promote the development of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) phases under ambient curing conditions, leading to a significant improvement in mechanical strength19,20. So far, only one study has investigated VT/BFS binary systems. Zihao et al.13 investigated the effect of blast furnace slag (BFS) incorporation on the compressive strength of volcanic tuff-based geopolymer pastes, cured at 60 °C for 28 days. Their findings revealed that compressive strength increased with BFS content up to 20%, subsequently decreasing, thereby identifying an optimal proportion.

Presenting a novel avenue for sustainable construction materials, the potential of combining volcanic tuff and BFS as precursors in alkali-activated binders remains largely unexplored in existing research. Therefore, this study investigates the performance enhancement of Algerian volcanic tuff-based geopolymeric mortars through the strategic incorporation of BFS, ranging from 10 to 30%. Specifically, it aims to quantify the influence of varied curing regimes (ambient and 80 °C) on the resultant mortar’s workability, mechanical strength, and microstructural evolution. By leveraging the abundant local resource of Algerian volcanic tuff, this research seeks to not only contribute to the scientific understanding of alkali-activated material (AAM) systems but also to foster regional sustainable development within Algeria’s volcanic territories.

Materials and methods

Materials

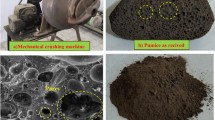

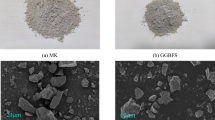

Precursor

The study utilized two primary raw materials, both sourced from Algeria: volcanic tuff and blast furnace slag. The volcanic tuff was extracted from the tuff quarry at Chetaibi (Koudiat Zoubia), operated by GRANU EST/GICA, located in the northeastern region of Annaba. The blast furnace slag was supplied by EPE SIDER ELHADJAR Spa, also based in Annaba. Prior to processing, both materials were dried at 105 °C to facilitate grinding. Afterward, they were ground and sieved to achieve a particle size of less than 80 μm, enhancing their reactivity. The specific surface area of the VT and BFS was measured using Blaine’s method21, yielding values of 4957 cm²/g and 3545 cm²/g, respectively. Their absolute densities were recorded as 2.58 g/cm³ for VT and 2.92 g/cm³ for BFS. Additionally, the chemical compositions of both materials were determined through X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, with the results presented in Table 1.

Alkaline solution

The alkaline solution employed in this study was formulated by mixing sodium hydroxide (SH), with a purity of about 99.5%, sourced from INOVYN (a subsidiary of INEOS), and sodium silicate (SS), provided by ADWAN CHEMICALS COMPANY. The sodium silicate solution’s composition by weight consisted of 28.8% SiO₂, 14.2% Na₂O, and 57% H₂O.

Methods

The experimental procedure adopted in this study involved the synthesis of geopolymer mortars using volcanic tuff, blast furnace slag, and an alkaline solution. First, a 10 M sodium hydroxide solution was prepared and combined with sodium silicate to achieve a silica modulus of 1 (SiO₂/Na₂O). After allowing the solution to rest for 24 h, it was mixed with the volcanic tuff and blast furnace slag in the proportions outlined in Table 2. To refine the scope of this study, preliminary tests were conducted, leading to the selection of BFS proportions within the range of 10%, 20%, and 30%. The water/binder ratio chosen for this study (0.48) was selected to ensure that mixes composed entirely of volcanic tuff would present acceptable workability, allowing easy casting. In addition, the sand/binder ratio (S/B) was set at 2. The mortar mixture was then homogenized for 5 min before being poured into molds measuring 40 × 40 × 160 mm and vibrated for 2 min to ensure uniformity. The samples were subsequently cured under two thermal conditions: ambient temperature and 80 °C for 48 h. The elevated curing temperature of 80 °C was chosen to enhance the geopolymerization process by increasing the mobility of dissolved species, thereby minimizing the need for large quantities of activator a consideration driven by economic and health concerns. Figure 1 shows the various stages of mortar preparation.

Testing methods and instruments

Compressive and flexural strengths of geopolymer mortar mixes were assessed at 7 and 28 days in accordance with EN 196-1 using the average of 3 flexural tests and 4 compressive tests. Figure 2 shows the flexural and compressive strength test setup. Setting time was measured using the Vicat “VICATRONIC IGM” automatic tester, in accordance with European standard EN 196-3. Figure 3 shows the setting time test. The slump of geopolymer mortars was tested using a mini-cone of dimensions D1 = 7 mm, D2 = 100 mm, and H = 6 mm, where D1, D2, and H represent the top diameter, bottom diameter, and height of the cone respectively. Figure 4 illustrates the slump test. The flow time of geopolymer mortars was evaluated using a type B maniabilimeter, as specified in standard NF P18-452. Figure 5 shows the type B maniabilimeter.

Microstructural analysis was carried out on samples selected after the compressive strength tests. These samples were crushed in a jaw crusher and analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) using a “Bruker” instrument, with a measurement range of 200 to 5000 cm− 1.

Result and discussion

Study of fresh geopolymer mortars

Setting time

The setting time of geopolymer pastes comprising VT and VT-BFS mixtures of standardized consistency was investigated. The data concerning the initial and final setting times are summarized in Table 3. The findings reveal that pastes composed of 100% VT exhibit significantly prolonged setting times. Specifically, the setting time for the VT paste exceeds 48 h, which is in line with previous literature16,22. This delayed setting behavior is attributed to the high degree of crystallinity in VT, which hinders the dissolution kinetics, thus necessitating thermal treatment to enhance the geopolymerization process, particularly during the initial stages, limiting the use of these mortars in precast elements. Conversely, the incorporation of BFS into the paste formulations resulted in a marked reduction of the setting time. The initial setting time of the paste incorporating 10% BFS was approximately 325 min, significantly shorter than the corresponding value for the 100% VT paste. A stepwise increase in BFS content, from 10 to 20% and from 10 to 30%, resulted in progressive reductions in initial setting time by 14% and 33%, respectively. A similar trend was observed in the final setting times, with reductions of 17% and 34%, consistent with findings reported in the literature23,24. The improved setting times observed with BFS compared to VT are primarily attributed to the higher chemical reactivity of BFS. This enhanced reactivity is primarily linked to its elevated CaO content, as calcium oxide (CaO) constitutes the predominant chemical component of BFS. The acceleration of the hydration process in the presence of higher CaO concentrations has been extensively validated by numerous studies22,25. Lime from BFS readily reacts with water, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃), promoting rapid geopolymerization reactions. In contrast, the dissolution of VT occurs exclusively in highly alkaline conditions and at a much slower rate, resulting in extended reaction times. Furthermore, BFS-based alkali-activated binders have been demonstrated to exhibit rapid hardening due to the interaction of Ca²⁺ ions with reactive silica (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃), facilitating the swift formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) phases. These phases are critical in accelerating the hardening process, thus reducing the overall setting time26. However, the BFS from El-Hadjar displays a moderate reactivity in alkaline environments, notably lower than reported in general literature27,28,29. This characteristic is likely due to the material’s lower calcium oxide (33.53%) and aluminate (5.08%) content. This rapid setting is crucial for faster project, emergency repairs and cold-weather construction, improving efficiency and resilience. Precast production and shotcrete applications also benefit significantly from the quicker hardening.

Workability

It is worth noting that the workability of geopolymer mortars based on VT is a topic that has not been extensively explored in the existing literature. For this study. The sand-to-binder ratio (S/B) was fixed at 2, based on previous findings in geopolymer research indicating that higher S/B ratios (above 2) significantly reduce both workability and mechanical strength30,31. With all other parameters held constant, the influence of BFS content on the workability of geopolymer mortars can be assessed. The effect of BFS content, ranging from 0 to 30%, on the flow time and slump of VT-based geopolymer mortars is depicted in Fig. 6. The results show that the increase in mortar slump is proportional to the increase in BFS content in the mix. Replacing 10% of VT with BFS significantly improves the slump, with an increase of around 14.54%. When the BFS content increases from 10 to 20% and from 20 to 30%, the slump flow increases by approximately 6,38% and 6,81%, respectively. This phenomenon could be attributed to the higher specific surface area of VT compared to BFS (4957 cm²/g vs. 3545 cm²/g), which leads to a greater demand for water to maintain consistent workability. Comparable results were found by Jafari Nadoushan, M32, who studied the rheological behavior of geopolymer pastes with varying pumice substitution for BFS (0–100%).

On the other hand, dynamic conditions (maniabilimeter flow time) showed a similar trend, but with a stronger effect. Replacing 10% of VT with BFS dramatically decreased flow time from 48.74 s to 15.42 s. Further increases in BFS substitution, to 20% and 30%, progressively reduced flow time to 8.37 and 3.86 s, respectively. This reduction can be attributed to the BFS particles, with their smoother and more spherical morphology, reduce interparticle friction compared to the angular VT particles (Fig. 7), facilitating easier flow. Additionally, BFS’s finer particle size distribution fills voids, creating a denser and more lubricated matrix. Furthermore, BFS’s lower water demand allows for enhanced flow without the detrimental effects of excess water on strength. The higher chemical reactivity of BFS also contributes by forming lubricating gels. This combination of factors, even with a relatively small 10% replacement, significantly alters the rheological properties of the geopolymer mixture, resulting in a substantial improvement in flowability. The dramatic improvement in flowability with the addition of BFS translates to significant real-world construction benefits. Easier placement and reduced labor are immediate advantages, particularly in complex formwork or confined spaces. Enhanced flow allows for better consolidation, minimizing voids and improving structural integrity.

Study of hardened geopolymer mortars

Mechanical strength

Curing at 80 °C

Figure 8 presents the compressive strength (CS) and flexural strength (FS) results of geopolymer mortars cured at 80 °C after 7 and 28 days. These findings reveal that both CS and FS values for all mixtures increase slightly over time, indicating that the majority of the mechanical strength is achieved early in the curing process. The mortar mixture containing 100% VT exhibits the lowest CS values, with 4.05 MPa at 7 days and 5.59 MPa at 28 days, and similarly low FS values of 2.15 MPa and 3.09 MPa at the same intervals. These results can be attributed to the relatively low geopolymeric reactivity of VT, which may require a significantly longer thermal treatment than 48 h to sustain the geopolymerization process and promote the formation of a larger quantity of geopolymeric gel. This gel can fully encapsulate the sand particles in the mixture, as shown in a study by Hamdi et al.30, which demonstrated that prolonged thermal curing is crucial for maintaining geopolymerization, with over 60% of CS and 50% of FS developing between 7 and 28 days in natural pozzolan-based geopolymers. The low mechanical strength could also be linked to the high water-to-binder ratio (0.48), as an excess of liquid inhibits the diffusion of dissolved species, slowing the polycondensation rate and thus reducing strength33.

For mortars containing BFS, partial substitution of VT with BFS (ranging from 10 to 30%) significantly influenced the mechanical performance of the geopolymer mortars at both 7 and 28 days. As seen, the CS values for mortars with 10%, 20%, and 30% BFS at 7 and 28 days were on average 1.53, 2.38, and 2.77 times higher than those of mortars containing 100% VT. Similarly, the FS values for these same mixtures were 1.28, 1.63, and 1.94 times higher, respectively. This enhancement in mechanical strength can be attributed to two factors. Firstly, BFS’s higher reactivity compared to VT, due to its elevated calcium oxide (CaO) content, leads to the formation of hydration products primarily composed of C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels34. Secondly, the combination of VT with the alkaline activation solution (NaOH and Na₂SiO₃) typically results in the formation of an N-A-S-H type geopolymer gel. However, in binary systems of NP and BFS, as demonstrated by Puligilla et al.35, and Ismail et al.36, the incorporation of ≤ 25% BFS led to the formation of an N-A-S-H geopolymer gel with calcium incorporation, creating a gel described as (C, N)-A-S-H. The formation of a sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) gel, alongside calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) gel, contributes to moderate improvements in the mechanical properties of the binder. This observation aligns with the findings of Mehsas et al.37, who demonstrated the enhanced reactivity of El-Hadjar BFS at elevated temperatures. Their research revealed that the incorporation of El-Hadjar BFS into metakaolin-based geopolymer pastes, cured at 60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C, resulted in significant enhancements in mechanical performance. This increased reactivity at higher temperatures can be attributed to the accelerated dissolution of BFS phases, promoting the formation of denser and more interconnected gel networks. Furthermore, considering the local availability of El-Hadjar BFS these findings underscore the potential for developing high-performance alkali-activated materials utilizing local resources. This suggests that the synergistic interaction between volcanic tuff and El-Hadjar BFS, particularly under elevated curing conditions, could lead to the production of durable and sustainable construction materials suitable for regional applications.

Curing at ambient temperature

The results of compressive and flexural strength for geopolymer mortars cured at ambient temperature at 7 and 28 days are presented in Fig. 9. These findings indicate a notably different behavior compared to mortars cured at 80 °C. Initially, mortars containing 100% VT exhibited relatively low CS and FS values at 7 days, with measurements of 2.42 MPa and 2.02 MPa, respectively. However, a pronounced increase in these values was observed at 28 days, where CS and FS reached 11.83 MPa and 9.34 MPa, representing increases of 388.84% and 362.37%, respectively, over the initial values. This behavior highlights the sluggish kinetics of geopolymerization in VT at early ages when cured under ambient conditions, with a noticeable acceleration in reaction rate over time. Such behavior has also been reported by Firdous et al.38 in their investigation of alkali-activated natural pozzolans, as well as by Ilker Tekin16, who observed that Turkish VT-based geopolymer mortars exhibited optimal early-age compressive strength at 75 °C but achieved peak strength values (46 MPa) at 90 days under ambient curing conditions. These findings are consistent with the observed setting time results.

Partial substitution of VT by BFS resulted in improved mechanical performance at 7 days across all studied geopolymer mortar mixes. The compressive strength of mortars incorporating 10, 20, and 30% BFS was 2.17, 2.74, and 3.73 times higher than those of the 100% VT mix, respectively. However, at 28 days, the addition of 10% BFS led to a significant reduction in CS of 45.7%. Increasing the BFS content from 10 to 20% and from 20 to 30% improved CS values by 6.8% and 54%, respectively. Despite these improvements, the CS of these mixes remained below that of the 100% VT mortar (11.83 MPa). Similar trends were observed in FS values, exhibiting a comparable pattern. We hypothesized that the observed reduction in compressive strength under ambient curing conditions could be attributed to a decrease in compatibility between VT and BFS over time. The slower reaction kinetics at ambient temperatures likely resulted in a less homogeneous geopolymer matrix, particularly with increasing BFS content. Furthermore, unreacted BFS particles at 28 days may have acted as stress concentrators, contributing to the strength reduction. The semi-crystalline nature of VT, leading to slower geopolymerization and limited early-stage N-A-S-H gel formation, likely played a significant role. While the partial incorporation of BFS (≤ 25%) initially accelerated polycondensation, it may have ultimately hindered continuous geopolymerization of VT. The lack of sufficient heat energy in ambient curing likely slowed BFS dissolution and reaction, resulting in a less dense and robust geopolymer structure. This behavior can be explained by the inherent incompatibility between VT and BFS under ambient conditions. The slow geopolymerization of VT, combined with the accelerated polycondensation induced by BFS, likely resulted in a substantial portion of unreacted VT acting as inert fillers, thus lowering mechanical properties. Moreover, the low alumina oxide content (5.08%) of El-Hadjar BFS may have exacerbated these effects. An increased Si/Al mass ratio, as introduced by BFS, likely promoted the formation of a Si-rich, amorphous gel, leading to reduced mechanical strength, consistent with findings by Allahverdi et al.39. This aligns with studies demonstrating a negative correlation between the Si/Al ratio and geopolymer binder strength40.

Water absorption

The water absorption percentages of geopolymer mortars cured at 80 °C and room temperature after a 28-day curing period are shown in Fig. 10. Water absorption rates for mortars cured at 80 °C range from 12.18 to 9.98%. In particular, the mortar composed entirely of VT has the highest water absorption rate, at 12.18%. The observed high water absorption is directly attributable to the inherent microstructure of the mix, which is characterized by substantial void space and porosity. This porous structure arises from incomplete geopolymerization, leading to an inadequate formation of the N-A-S-H gel, the primary binding phase. Consequently, the lack of a dense, well-connected gel matrix allows for increased water ingress and retention within the material’s internal voids.

The influence of blast furnace slag (BFS) on water absorption in volcanic tuff (VT) based geopolymers exhibits a distinct temperature-dependent trend. When cured at 80 °C, increasing BFS content demonstrably reduces water absorption. Specifically, absorption rates decrease by 10.26%, 13.22%, and 18.06% with 10%, 20%, and 30% BFS additions, respectively. This reduction is attributed to the progressive formation of calcium-aluminum-silicate-hydrate (C-A-S-H) gel, which possesses a higher water-binding capacity compared to the sodium-aluminum-silicate-hydrate (N-A-S-H) gel predominantly derived from VT41. Consequently, the decreased water absorption reflects a reduction in matrix porosity, aligning with the enhanced compressive (CS) and flexural strengths (FS) observed.

However, ambient curing conditions reveal a contrasting behavior. The 100% VT mixture exhibits the lowest water absorption (8.37%), significantly lower than BFS-modified mortars. This is likely due to the formation of a denser N-A-S-H gel network during prolonged ambient geopolymerization, resulting in reduced porosity, which is also supported by the mechanical strength results. Conversely, increasing BFS content at ambient temperature leads to a substantial increase in water absorption, with increments of 29.5%, 38.1%, and 32.6% for 10%, 20%, and 30% BFS, respectively. This phenomenon suggests that under ambient conditions, BFS may disrupt the optimal geopolymerization kinetics. It is postulated that BFS particles rapidly consume available hydroxide ions (OH⁻), essential for VT dissolution, hindering the release of silica and alumina species necessary for N-A-S-H formation. This leads to incomplete geopolymerization, resulting in a more porous matrix with higher void content and increased water absorption.

The observed water absorption trends consistently correlate with the mechanical performance data, underscoring the critical relationship between matrix porosity, the nature of hydration products (C-A-S-H vs. N-A-S-H), and the overall performance of these geopolymer mortars. The curing temperature significantly influences the dominant reaction pathway, with elevated temperatures favoring C-A-S-H formation and porosity reduction, while ambient curing can lead to disruptive BFS interactions.

Microstructural study of geopolymer mortars

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR spectra of VT powder, BFS, and selected geopolymer mortar mixtures (100% VT and 30% BFS) cured at ambient temperature and at 80 °C are illustrated in Fig. 11. The BFS composition primarily consists of amorphous, highly reactive calcium and aluminosilicate components. VT powder, on the other hand, is characterized by chemically stable aluminosilicate minerals. A prominent observation from these results is the emergence of a band at 875 cm− 1 across all geopolymer mortar mixtures, with varying intensities. This band is indicative of less polymerized products and corresponds to the vibration of Si-OH groups, signifying a degree of unreacted material within the mixtures42.

All FTIR spectra of geopolymer mortars show an absorption band at 2328 cm− 1, associated with the O-H stretching vibration. This feature is attributed to chemically bound water, indicating the presence of an N-A-S-H gel in the mortar43. Except the 100% VT mix cured at 80 °C, indicating extremely limited geopolymerization. This limitation can be attributed to the premature evaporation of water before the completion of the dissolution stage, which requires a prolonged curing time for optimum reaction. This results in less polymerized products, as shown by the highest intensity of the band at 875 cm-1 in this mixture.

Conversely, the FTIR spectrum of the same 100% VT mixture cured at ambient temperature displays notable changes. Specifically, the band at 709 cm− 1, corresponding to the bending vibration of Si-O-Si, disappears, and the intensity of the band around 997 cm− 1, associated with the symmetrical stretching vibration of Si-O-T (where T represents Si or Al), diminishes. These alterations indicate a significant dissolution of these bonds, leading to an enhanced polycondensation of a larger quantity of geopolymer gel. This is further evidenced by the decrease in intensity of the band at 875 cm− 1 and the emergence of the geopolymer gel band at 2328 cm− 1. These observations align closely with the mechanical strength results, confirming the correlation between the degree of geopolymerization. The FTIR spectrum of the 30% BFS blended mortar (VT-BFS30) cured at ambient temperature exhibited a pattern notably similar to that of the 100% VT mixtures cured under identical conditions. This similarity corroborated the relatively close compressive strengths observed for these mixtures, measuring 9.89 MPa and 11.83 MPa, respectively, indicating that at ambient temperature the BFS at 30% did not significantly alter the primary geopolymerization products. However, the FTIR spectrum of the VT-BFS30 mixture cured at 80 °C revealed significant changes, including the disappearance of bands located at 532 and 752 cm− 1. These changes indicated the complete dissolution of the corresponding bonds, suggesting a more thorough reaction and structural transformation under elevated curing. Furthermore, the decrease in intensity and a shift of the primary band at 997 cm− 1 to a lower wavenumber of 972 cm− 1 suggested substantial structural reorganization within the mixture, indicating a higher degree of polymerization and formation of a denser N-A-S-H gel44,45. The primary explanation for these observations lies in the higher energy content of silicon compared to aluminum, which leads to a decrease in intensity and a shift of the band associated with the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si/Al as the number of aluminum atoms in the final product increases46. This shift serves as an indicator of the degree of polymerization of the geopolymers. These findings are also consistent with the optimal compressive strength observed for this mixture, recorded at 15.03 MPa. Furthermore, the band observed between 1401 cm− 1 and 1430 cm− 1 corresponds to the O-C-O stretching vibration, which is formed due to atmospheric carbonation of unreacted Na⁺ ions during the geopolymerization process47,48. We correlated these findings with the observed higher compressive strengths at 80 °C, demonstrating that the enhanced polymerization and structural reorganization directly contributed to improved mechanical performance. We further discussed how these changes in Si-O-Al bonds and the degree of polymerization could influence the durability of the mortars, suggesting that the denser, more polymerized structure at 80 °C would likely result in reduced permeability and improved resistance to aggressive environmental conditions. By expanding on the FTIR results and connecting them to mechanical performance and durability, we aimed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the microstructural changes occurring in our geopolymer mortars.

Conclusion

This study investigates the effects of incorporating BFS on the properties of volcanic tuff-based geopolymers, specifically regarding setting time, compressive and flexural strength, workability, water absorption, and microstructure. The findings from this study lead to the following conclusions:

-

Volcanic tuff geopolymer pastes demonstrate prolonged setting times due to their limited early-age geopolymeric reactivity. However, the replacement of even small percentages of volcanic tuff with Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) notably reduces the setting time.

-

Partial replacement of volcanic tuff with Blast Furnace Slag (BFS) significantly enhances the workability (slump and flow time) of geopolymer mortars. This improvement is attributed to reduced water demand and decreased interparticle friction.

-

Mortars made entirely of volcanic tuff (VT) exhibit a slow geopolymerization reaction under ambient curing due to their semi-crystalline nature. Adding up to 30% blast furnace slag (BFS) significantly accelerates early-age reactivity, achieving maximum strength at 7 days. However, the extended geopolymerization of 100% VT mortars results in higher 28-day strength.

-

Increasing the curing temperature to 80 °C for 48 h slightly enhances the mechanical strength of the 100% VT mixture at 7 days, while inhibiting the development of strength beyond this period. Additionally, raising the BFS content in the mixture significantly improves mechanical properties at both 7 and 28 days, attributed to the incorporation of calcium into the formed N-A-S-H gel and/or the further formation of C-S-H or C-A-S-H gels.

-

The prolonged geopolymerization process in mortars composed solely of volcanic tuff yielded the lowest water absorption, likely due to increased geopolymer gel formation.

-

The microstructural analysis consistently validated the observed mechanical strength and setting time trends, providing direct evidence of the mechanisms driving the performance of volcanic tuff-BFS geopolymer pastes.

The results of experimental investigations demonstrate the viability of incorporating blast furnace slag (BFS) into volcanic tuff-based geopolymers, yielding materials suitable for sustainable construction, notably earth block and plastering applications. Critically, these findings confirm the potential to consistently meet or surpass the Algerian standard NA 5020’s strength requirements (5 MPa compressive, 2 MPa flexural), ensuring robust performance in residential and commercial projects. This achievement, coupled with the circular economy benefits of BFS utilization through industrial waste repurposing, significantly reduces the environmental impact of construction materials within our region, where volcanic tuff and industrial byproducts are abundant.

Future research should comprehensively explore several key areas. Firstly, a broader investigation of curing conditions is necessary, encompassing wider temperature and duration ranges, including extended ambient curing, alongside an analysis of varying humidity levels. Secondly, optimizing blast furnace slag (BFS) content to achieve maximum mechanical performance while minimizing water absorption is crucial. hirdly, non-destructive testing and long-term performance studies are recommended to evaluate durability under a range of environmental conditions. Fourthly, exploring alternative alkaline activators to enhance the geopolymerization process warrants attention. Fifthly, detailed microstructural analysis using advanced techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) would provide valuable insights. Sixthly, performing life cycle assessments (LCA) is essential for evaluating environmental impact and sustainability. Finally, implementing pilot projects and field tests will validate laboratory findings in real-world construction scenarios.

Data availability

Data associated with the study will be available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

Duxson, P. et al. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the Art. J. Mater. Sci. 42, 2917–2933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-0637-z (2007).

Firdous, R., Stephan, D. & Djobo, J. N. Y. Natural Pozzolan based geopolymers: A review on mechanical, microstructural and durability characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 190, 1251–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.191 (2018).

Pacheco-Torgal, F., Castro-Gomes, J. & Jalali, S. Alkali-activated binders: A review. Part 2. About materials and binders manufacture. Constr. Build. Mater. 22, 1315–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.03.019 (2008).

Pacheco-Torgal, F., Castro-Gomes, J. & Jalali, S. Alkali-activated binders: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 22, 1305–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.10.015 (2008).

McLellan, B. C., Williams, R. P., Lay, J., Van Riessen, A. & Corder, G. D. Costs and carbon emissions for geopolymer pastes in comparison to ordinary Portland cement. J. Clean. Prod. 19, 1080–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.02.010 (2011).

IEA, C. Technology Roadmap-Low-Carbon Transition in the Cement Industry. Analysis. IEA https://www.iea.org/reports/technology-roadmap-low-carbon-transition-in-the-cement-industry (2018).

Ouellet-Plamondon, C. & Habert, G. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of alkali-activated cements and concretes. in Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes 663–686, Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1533/9781782422884.5.663 (2015).

Sakir, S., Raman, S. N., Safiuddin, M., Kaish, A. B. M. A. & Mutalib, A. A. Utilization of by-products and wastes as supplementary cementitious materials in structural mortar for sustainable construction. Sustainability 12, 3888. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093888 (2020).

Mohamad, N., Muthusamy, K., Embong, R., Kusbiantoro, A. & Hashim, M. H. Environmental impact of cement production and Solutions: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 48, 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.212 (2022).

Komnitsas, K. A. Potential of geopolymer technology towards green buildings and sustainable cities. Procedia Eng. 21, 1023–1032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2108 (2011).

Shi, C., Jiménez, A. F. & Palomo, A. New cements for the 21st century: The pursuit of an alternative to Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 41, 750–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.03.016 (2011).

Boumaza, A., Khouadjia, M. L. K., Oualid, H. & Alioui, H. Volcanic tuff as a Raw material for alkali-activated materials. IJANSER 7, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.59287/ijanser.1331 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. Microstructure and mechanical performance of alkali-activated tuff-based binders. Cem. Concr. Compos. 139, 105030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105030 (2023).

Bondar, D., Lynsdale, C. J., Milestone, N. B., Hassani, N. & Ramezanianpour, A. A. Effect of type, form, and dosage of activators on strength of alkali-activated natural Pozzolans. Cem. Concr. Compos. 33, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2010.10.021 (2011).

Najafi Kani, E. & Allahverdi, A. Effects of curing time and temperature on strength development of inorganic polymeric binder based on natural Pozzolan. J. Mater. Sci. 44, 3088–3097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-009-3411-1 (2009).

Tekin, I. Properties of NaOH activated geopolymer with marble, travertine and volcanic tuff wastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 127, 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.10.038 (2016).

Kantarcı, F., Türkmen, I. & Ekinci, E. Optimization of production parameters of geopolymer mortar and concrete: A comprehensive experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 228, 116770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.116770 (2019).

Barış, K. E. & Tanaçan, L. Improving the geopolymeric reactivity of Earth of Datça as a natural Pozzolan in developing green binder. J. Building Eng. 41, 102760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102760 (2021).

Tchakoute Kouamo, H., Mbey, J. A., Elimbi, A., Kenne Diffo, B. B. & Njopwouo, D. Synthesis of volcanic Ash-based geopolymer mortars by fusion method: Effects of adding Metakaolin to fused volcanic Ash. Ceram. Int. 39, 1613–1621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.08.003 (2013).

Vafaei, M. & Allahverdi, A. Influence of calcium aluminate cement on geopolymerization of natural Pozzolan. Constr. Build. Mater. 114, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.204 (2016).

EN196-6 Method of testing cement Part 6: Determination of fineness. (1990).

Robayo-Salazar, R. A., De Gutiérrez, M. & Puertas, F. Study of synergy between a natural volcanic Pozzolan and a granulated blast furnace slag in the production of geopolymeric pastes and mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 157, 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.09.092 (2017).

Aziz, A. et al. Effect of blast-furnace slag on physicochemical properties of pozzolan-based geopolymers. Mater. Chem. Phys. 258, 123880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.123880 (2021).

Değirmenci, F. N. Utilization of natural and waste Pozzolans as an alternative resource of geopolymer mortar. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 16, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-016-0115-1 (2018).

Jindal, B. B. Investigations on the properties of geopolymer mortar and concrete with mineral admixtures: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 227, 116644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.08.025 (2019).

Najimi, M. Alkali-Activated Natural Pozzolan/Slag Binder for Sustainable Concrete. (University of Nevada, Las Vegas). https://doi.org/10.34917/10083182 (2016).

Alioui, H. et al. Investigation of the effect of commercial limestone on alkali-activated blends based on Algerian slag-glass powder. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 26, 8049–8072. https://doi.org/10.1080/19648189.2021.2018047 (2022).

Boumediene, M. ÉTUDE DES PROPRIÉTÉS DES MATÉRIAUX GÉOPOLYMÉRES ÉTUVÉS. (2022).

Silva, P. D., Sagoe-Crenstil, K. & Sirivivatnanon, V. Kinetics of geopolymerization: Role of Al2O3 and SiO2. Cem. Concr. Res. 37, 512–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.01.003 (2007).

Hamdi, O. M., Ahmed-Chaouch, A., Saïdani, M. & Alioui, H. Use of the Algerian natural Pozzolan for the production of a geopolymer as a complete cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 400, 132723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132723 (2023).

Khan, M. Z. N., Shaikh, F. U. A., Hao, Y. & Hao, H. Effects of curing conditions and Sand-to-Binder ratios on compressive strength development of fly Ash geopolymer. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 30, 04017267. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002119 (2018).

Jafari Nadoushan, M. & Ramezanianpour, A. A. The effect of type and concentration of activators on flowability and compressive strength of natural Pozzolan and slag-based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 111, 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.086 (2016).

Bature, A. S., Khorami, M., Ganjian, E. & Tyrer, M. Influence of alkali activator type and proportion on strength performance of calcined clay geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 267, 120446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120446 (2021).

Tekin, İ. et al. Effect of waste travertine powder on properties of rhyolitic tuff-based geopolymer. J. Building Eng. 96, 110429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110429 (2024).

Puligilla, S. & Mondal, P. Role of slag in microstructural development and hardening of fly ash-slag geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Res. 43, 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.10.004 (2013).

Ismail, I. et al. Modification of phase evolution in alkali-activated blast furnace slag by the incorporation of fly Ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 45, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.09.006 (2014).

Mehsas, B., Siline, M. & Zeghichi, L. The effect of using low reactive Metakaolin on performances of geopolymer binder. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 7, 233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-022-00833-9 (2022).

Firdous, R. & Stephan, D. Effect of silica modulus on the geopolymerization activity of natural Pozzolans. Constr. Build. Mater. 219, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.161 (2019).

Allahverdi, A., Kani, E. N. & Yazdanipour, M. Effects of blast-furnace slag on natural pozzolan-based geopolymer cemenT. (2011).

Wan, Q. et al. Geopolymerization reaction, microstructure and simulation of metakaolin-based geopolymers at extended Si/Al ratios. Cem. Concr. Compos. 79, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.01.014 (2017).

Najimi, M. & Ghafoori, N. Engineering properties of natural Pozzolan/slag based alkali-activated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 208, 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.107 (2019).

Tchakoute Kouamo, H., Elimbi, A., Mbey, J. A., Sabouang, N., Njopwouo, D. & C. J. & The effect of adding alumina-oxide to Metakaolin and volcanic Ash on geopolymer products: A comparative study. Constr. Build. Mater. 35, 960–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.023 (2012).

Tchakoute, H. K., Elimbi, A., Yanne, E. & Djangang, C. N. Utilization of volcanic ashes for the production of geopolymers cured at ambient temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 38, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.03.010 (2013).

García-Lodeiro, I., Fernández-Jiménez, A., Blanco, M. T. & Palomo, A. FTIR study of the sol–gel synthesis of cementitious gels: C–S–H and N–A–S–H. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 45, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-007-1643-6 (2008).

Bagci, C., Tameni, G., Elsayed, H. & Bernardo, E. Sustainable manufacturing of new construction material from alkali activation of volcanic tuff. Mater. Today Commun. 36, 106645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106645 (2023).

Fernández-Jiménez, A. & Palomo, A. Mid-infrared spectroscopic studies of alkali-activated fly Ash structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 86, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2005.05.057 (2005).

Djobo, Y. J. N., Elimbi, A. & Dika Manga, J. Djon Li Ndjock, I. B. Partial replacement of volcanic Ash by bauxite and calcined oyster shell in the synthesis of volcanic Ash-based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 113, 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.104 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Utilizing municipal solid waste incineration bottom Ash and volcanic tuff to produce geopolymer materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 425, 136015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136015 (2024).

Funding

This research received no external funding. Open access funding provided by York University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Project Administration, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing – review & editing: M.L.K.K., H.F.I., M.K.; Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Software, Validation, Data Curation, Resources, Writing – original draft: A.B., M.L.K.K., H.F.I., O.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boumaza, A., Khouadjia, M.L.K., Isleem, H.F. et al. Effect of blast furnace slag on the fresh and hardened properties of volcanic tuff-based geopolymer mortars. Sci Rep 15, 13651 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98382-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98382-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of alkaline activator concentration on mechanical properties and microstructure of a ternary blended one-part geopolymer cement

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Experimental and GEP-based evaluation of compressive strength in eco-friendly mortars with waste foundry sand and varying cement grades

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Performance based evaluation of black cotton soil geopolymer mortar on fresh properties, mechanical strength, durability, and molecular dynamics correlation

Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design (2025)