Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a worldwide epidemic that leads to significant changes in foot shape, deformities, and ulcers. Precise classification of diabetic foot not only helps identify foot abnormalities but also facilitates personalized treatment and preventive measures through the engineering design of foot orthoses. In this study, we propose a novel deep learning method based on DiffusionNet which incorporates a self-attention mechanism and external features to classify the foot types of diabetic patients into six categories by using simple 3D foot images directly. Our approach achieves a high accuracy of 82.9% surpassing existing machine and deep learning methods. The proposed model offers a cost-effective way to analyse foot shapes and facilitate the customization process for both the footwear industry and medical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Feet are the irreplaceable components of the human body to support daily activities, which are composed of 26 bones, 33 joints and more than 100 tendons, muscles and ligaments1. The shape of the foot is highly varied in terms of sex, age, weight, physical health and race2. Precise foot type classification is an important aspect in the fields of orthopaedics, sports sciences and footwear design, providing effective and personalized care and improving overall foot health and performance. Various foot type classifications have been developed for children, adolescents, young and healthy adults3,4. Recently, a system that combined three-dimensional (3D) statistical shapemodellingg (SSM), multivariate regression and statistical testing has been proposed by Stankovic et al. to identify 3D foot shape abnormalities among healthy individuals5. Due to pathophysiology and complications of diabetes mellitus, foot problems and deformities are commonly found for patients and result in significant changes in foot shape, such as foot ulcers, limited motion of the joint, hammer toe, claw toe and bunion6. A previous study found that diabetic patients have a wider forefoot width and lower foot length to foot width ratio than those without diabetes7. However, foot anthropometry of diabetic patients and their foot type classification has not been well-established, resulting in major problems of discomfort and poor fit of footwear.

Identifying foot arch shapes and anthropometric variabilities is particularly crucial for clinical and rehabilitative purposes in developing personalized treatment plans for foot-related problems, and enhancing the foot sizing system for better comfort and support. The shape of the foot arch is typically classified into three types, including planus (flat foot), rectus (normal foot) and cavus (high arch), through traditional footprint parameters, visual assessment, anthropometric numerical data and radiographic evaluation8, which requires higher professionalism but at the same time is time-consuming and prone to human errors. Previous studies have classified the foot shape of children, adolescents, and young adults into three types respectively based on the anthropometric foot measurements obtained from 3D foot images by using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis3,9. A data-driven approach based on Archetypoid Analysis (ADA) is also proposed to classify Spanish adult males and females into three archetypal feet10. As the foot has a complex structure with intricate anatomical, biomechanical and functional characteristics, its diversity in foot shapes might not be fully captured by the three types of foot. Mei et al. have classified the foot type based on the acceleration, angular velocity, and force data collected from sensor-enabled shoes and classified using a one-dimensional convolutional neural network11. However, these numerical data are indirect measures and could not clearly reflect the intrinsic geometry and features of the 3D foot shape. Relying on sensor data requires people to wear sensor-enabled insoles or similar devices, which may not be practical or comfortable for long-term or large-scale uses.

With the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), image classification, detection and segmentation have been widely adopted for medical images, early diagnosis of diseases, fashion apparel and ergonomic design. Deep learning methods are commonly applied for foot type classification to bring potential transformations to the footwear industry. With the use of AI, personalized insole and footwear can be designed and created with high accuracy and efficiency by analyzing large datasets and integrating various types of data without human bias. A fine-tuned visual geometry group-16 (VGG16) and multi-label classification algorithm based on ResNet-50 have been proposed to classify foot types using plantar pressure images4,12, which are high-performance Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based models and primarily designed for processing regular grid-like data and extract importance features from 2D-pixel data in images or 3D voxel grids. However, CNNs are primarily focused on local features and lack of handling global foot anatomy and variances in object position, orientation and scale. As the foot is presented in a 3D shape, classifying foot types directly from raw 3D point cloud data of the foot can further enhance the applications and accuracy of the classification results rather than 2D images. PointNet and PointNet++ have been employed for 3D object classification, human body segmentation and pose recognition13,14,15, which tackles irregular and unstructured point cloud data and capture more detailed geometric features directly from point coordinates. However, they may limit to the fine-grained details and local structures in foot shapes when compared to other methods that specifically designed for shape analysis and may affect the accuracy of classification results. Recently, DiffusionNet has been introduced as a new approach of directly handling different geometric representations of 3D surfaces for a wide applications of deformable surface segmentation, classification, unsupervised and supervised non-rigid shape matching, including both triangle meshes or point clouds16. This state-of-the-art method has excellent strength in capturing precise local features and is highly effective for spatial communication, but its application for 3D foot type classification is not explored.

In this article, we propose a novel deep learning method that incorporated self-attention mechanism and external features to enhance the accuracy and robustness of directly classifying foot types of diabetic patients from 3D foot images. This can simplify the diagnosis process and provide scientific guidance for clinical prescription, treatment, and prognosis to ensure objectivity. It can also improve the ergonomic design of products related to foot healthcare to achieve optimal comfort and fit.

Related works

In order to achieve the feature extraction and classification from 3D foot shapes, recent deep learning methods can be simply divided into the following four categories, including multi-view based methods, voxel-based methods, point-based methods and graph-based methods.

Multi-view based methods

To demonstrate the possibility of achieving 3D shape classification using a multi-view approach, researchers have introduced different novel CNN architectures, including Multi-View CNN (MVCNN)17 and group-view convolutional neural network (GVCNN)18, to process 3D shapes from a collection of rendered 2D images captured from multiple views and extracting image features to perform the classification. The performance of deep learning features in view-based 3D model retrieval has also been evaluated by Gao et al.19. However, the multi-view approach leads to a lack of global information perception and might not well describe the 3D spatial characteristics of objects, which resulted in difficulties for applying in scene segmentation and object detection tasks.

Voxel-based methods

3D shapes can be converted into a voxel format based on the volume they occupy in space for feature extraction and classification, like the voxel grid, or other types of 3D grid system. Maturana et al. proposed VoxNet that integrates a volumetric Occupancy Grid representation with a supervised 3D CNN to accurately recognized real-time objects and encompasses the capability to classify 3D shapes based on the learned features from the volumetric representation of the data20. Zhou et al. introduced VoxelNet to divide the point cloud into equally spaced 3D voxels and uses a novel voxel feature encoding (VFE) layer to transform points within each voxel for feature extraction and 3D object detection21. Wu et al. also developed a 3D ShapeNets model to handle voxelization directly for 3D shapes for feature extraction and classification22. However, voxelized model would result in lower resolution and information would be unavoidably lost during the voxelization process in comparison to the original model, and high-resolution outputs will necessitate larger usage of memory and higher computational resources.

Point-based methods

PointNet and PointNet++ network models have demonstrated strong performance in processing point cloud data directly through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) network for feature extraction and 3D shape classification. PointNet can process disordered point clouds directly for 3D object classification and segmentation15, but it has limitations in handling non-uniform point cloud densities and ignores the extraction of local features. To address these issues, PointNet++ has been introduced as an extension of PointNet to improve the capture of local features and spatial relationships within point clouds by incorporating a hierarchical feature learning approach23, but it still faces challenges when dealing with very large scenes and the operation of feature aggregation is time-consuming, especially for large point cloud. To allow traditional convolution operations to be applied directly on point clouds, Li et al. proposed PointCNN that used X-transformation to handle the irregular and unordered nature of point cloud data by learning to weight and permute the input features associated with each point24, however, it is more computationally intensive due to its transformation and convolution operations.

Graph-based methods

Unlike other methods, graph-based methods can naturally represent and model the topological structure and relationships between points (nodes) in the 3D shapes that benefit for capturing both local and global features. Kipf and Welling proposed a novel and scalable approach for semi-supervised learning on graph-structured data that based on a localized first-order approximation of spectral graph convolutions25. Wang et al. introduced a dynamic graph edge convolution module named EdgeConv to act on graphs dynamically computed in each layer of the network so as to improve the ability of obtaining local geometric features, but this method does not explicitly model the topological relationships between points and might pose challenges for certain classification tasks26. An integration of self-attention with PointView-Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) was proposed by Lai et al. to enhance the classification accuracy by allowing the model to weigh the importance of different points in the point cloud relative to each other, regardless of their spatial distance27.

Unfortunately, due to difficulties in handling diverse geometric representations and irregularities of foot shapes, the aforementioned methods on 3D foot shape classification are not fully exploited. Latterly, an efficient and robust approach to deep learning on 3D surfaces named DiffusionNet, introduced by Sharp et al., has demonstrated the ability of the network to be discretization agnostic by using a simple diffusion layer for spatial information communication. The DiffusionNet can handle various geometric representations such as triangle meshes or point clouds without performance degradation, and achieve state-of-the-art results on surface classification, segmentation, and non-rigid shape correspondence. As DiffusionNet represents a new contribution to the field of 3D shape classification and more broadly to geometric deep learning, further exploration is required for its potential applications, especially for 3D foot shapes. Our paper proposed a novel integration of DiffusionNet with self-attention mechanism to better capture global dependencies and relationships between different parts of a 3D shape for improving the performance on classification of 3D foot type.

Methodology

Data acquisition

A total of 114 diabetic patients aged between 50-77 years old (mean: 66; SD: 5.7) have been recruited for this study, including 50 males and 64 females with the presence of either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus in the early stage. They had no history of ulcers or the presence of active ulcers and were able to walk independently without using any walking aid. The body mass index and foot size of the female subjects range from 18.1 to 33.4 \(\text {kg/m}^2\) (mean: 23.7; SD: 3.3) and EU 34 to 43 respectively. Those of the male subjects range from 18.7 to 33.2 \(\text {kg/m}^2\) (mean: 23.8; SD: 3.1) and EU 37 to 44 respectively. All of the participants gave written informed consent before participating in the study. The experiment was approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University prior to starting the study (Reference Number: HSEARS20200128001). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

A handheld EinScan Pro HD 3D scanner with a foot station (SHINING 3D Tech Co., Ltd., China) was used to capture the shape deformation of the foot, including both dorsal and plantar sides. It can process up to 3, 000, 000 points per second under the handheld scan mode and deliver volumetric accuracy up to 0.045mm+0.3mm/m. During the scanning, the subjects were required to stand with their shoulder width apart and the body weight was equally loaded on each foot. Both left and right feet would be included for the analysis.

Label of foot types

To facilitate model training, the feet of diabetic patients were classified and labelled based on thirteen foot measurements (see Fig. 2). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to reduce the dimensionality of the foot data and extract main feature variables for describing the foot shape differences. This step is crucial in simplifying the complex dataset while retaining the essential characteristics of the foot shapes. Following PCA, A two-stage cluster analysis was subsequently performed to classify the foot shape types. Ward’s minimum variance method was first used to determine the optimal number of clusters feasible for the subsequent analysis, and then K-means clustering was applied to classify the foot shapes into distinct groups. Each foot type is described by its cluster centre foot data in terms of lateral ball length, ball width and instep height for both genders. As a result, three foot types were classified for females and males, respectively. For females, the first foot type is characterised by its short lateral ball length, medium ball width and low instep height (SML type). The second foot type is characterised by its medium lateral ball length, wide ball width and high instep height (MWH type). The third type is characterised by its long lateral ball length, narrow ball width and medium instep height (LNM type). Similarly for males, the first foot type with long lateral ball length, medium ball width and high instep height was defined as LMH type. The second foot type with short lateral ball length, wide ball width and medium instep height was defined as SWM type. The third foot type with medium lateral ball length, narrow ball width and low instep height was defined as MNL type.

Construction of model

Background

A 3D object can be represented in various ways, including point clouds, triangle meshes, voxels, etc. In order to process different 3D representations, different architectures are developed for them separately15,16,28. However, neither point clouds nor voxels can fully utilize the information contained in the 3D object. In this paper, we dedicatedly use triangle meshes as the representation of our input 3D data. We define the original input 3D shape as X with N vertices, while the 3D shape is represented by the vertex set V and the edge set E. Each vertex \(v \in V\) is its coordinate (x, y, z) plus extra features such as colors. For simplicity, we only use the coordinate for each vertex. And each edge \(e \in E\) is a tuple (a, b) indicating that the a-th vertex and the b-th vertex are connected. For the 3D foot type classification task, the 3D shape data is obtained by 3D scanning systems. The personal information and manual measurements for each subject are also recorded during the data collecting experiment. For each sample, our framework outputs k scores for all the k candidate classes while a larger score indicating a large probability belonging the corresponding class.

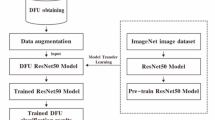

Network structure

The overall structure of our framework is illustrated in Fig. 1. It contains three main modules: point-wise feature extraction, attention-based feature fusion and incorporating external features. We will discuss the three modules in detail.

Point-wise feature extraction A feature extractor is used to extract point-wise features, i.e. HodgeNet29 and DiffusionNet16. In this paper, we use DiffusionNet for feature extraction based on three considerations.DiffusionNet is composed of multiple blocks, each containing a learned diffusion layer for spatial communication, spatial gradient features for directional filtering, and a point-wise MLP with residual connections respectively. Detailed description of the network structure can be found in the original paper. The reason for adopting DiffusionNet is three-fold. First, it is a state-of-the-art method that achieves superior performance on various applications. Second, it is applicable for both point clouds and triangle meshes, which makes it versatile for different scenarios. Third, DiffusionNet can extract topological and geometric information as well as incorporate external features on each vertex.

In this module, triangle meshes are processed by DiffusionNet to produce point-wise dense features:

where \(F_\text {diff} \in R^{N\times D}\) is the output point-wise features. N and D denote the number of vertices and the dimension of the feature respectively.

Attention-based feature fusion After obtaining the dense features from the previous step, the conventional way to process them is to use an average pooling or adaptive pooling operation. However, the importance for vertices of a 3D object is not uniformly distributed, especially for 3D foot data. Identifying key parts, e.g. ankle and toes, on the surface is essential for foot type classification.

To achieve this goal, we leverage the Self-attention mechanism30 to automatically address the importance on different point features. Specifically, the i-th vertex’s feature vector \(f_\text {diff}^i\) projected with matrix \(W^Q\) is used as the query and all other vertices’ feature vectors projected with matrix \(W^K\) are used as the keys. The attention score between the i-th vertex and the j-th vertex is calculated as the dot product of the query and the key, and then normalized by the square root of the dimension of the feature. After softmax, the attention scores are then used to compute a weighted sum of the feature vectors projected with matrix \(W^V\), leading to the output feature vector of the i-th vertex. In overall:

where \(F_\text {Attn}\) is the dense feature after the self-attention operation.

Incorporating external features To further improve the accuracy of foot type classification, we delicately utilize semi-automatic foot measurements for classification. Although deep-learning methods can extract features from raw data, it is still hard to fully utilize semantic information contained in the raw data. However, only relying on semi-automatic foot measurements depends on domain knowledge and it is not able to discover potential information in the data. In this paper, we incorporate 13 external semi-automatic foot measurements with extracted features to tackle this problem, which were obtained through a semi-automatic foot measurement model. To ensure measurement accuracy and data quality, manual labeling of 12 key landmarks is required on foot for the formulation of automatic foot local coordinates systems (LCSs) that is estimated by three steps below (see Fig. 2).

-

1.

3D scans cleaning with indicator landmarks The raw 3D scans may contain various disconnected parts, e.g. the foot, the boundary of the scanning pad, the trouser, etc. To separate the foot from the other parts, the average distances between these parts and all landmarks are calculated and the part with the shortest distance is selected while the others are removed. The remaining part is considered as the foot scan.

-

2.

PCA for major axis estimation Landmarks P2-P5 and P8-P9 are used to estimate the plantar plane with least squares. The plantar plane is then used to crop out the foot plantar, whose vertice coordinates are used to estimate the major axis via principal component analysis (PCA). Specifically, the origin of the LCS is set as the centroid of the foot plantar, the first principal component is set as the x-axis, the second principal component is set as the y-axis, and the cross product of the first and second principal components is set as the z-axis. Since PCA is determined only up to the sign, these axes are conditionally flipped to enforce that x-axis points from the heel to the toe (vector \(P_1\) - \(P_{10}\)) and z-axis points from the plantar to the dorsal side (vector \(P_{11}\) - \(P_8\)), leading to consistent orientations among local coordinates of different foot scan.

-

3.

Transformation to unified coordinates Convert the foot scans to the LCS, and then find the lowest z-coordinates, \(z_\text {min}\), among all vertices. To push the origin of the LCS to the ground level, convert \(0,0,z_\text {min}\) to the original (global) coordinates system and set it as the new origin of the LCS.

After that, all foot scans can be converted to their estimated LCSs. Since these LCSs possess consistent orientation and position, the foot scans are now aligned to a unified coordinates system with 13 comparable anthropometry measurements31, including the lengths of ball and foot; widths of foot, ball and heel; girths of ball and instep; heights of instep and ball; and angles of ball, first toe and fifth toe (see Fig. 2). Details of foot measurement metrics of the model are shown as below.

-

Measurements along axis Now that all foot scans are aligned to a unified coordinates system, the length, width, and height measurements can be calculated along the x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis, respectively.

-

Measurements of distance The distance between two landmarks \(P_a\) and \(P_b\) is calculated as the Euclidean distance between the two points \(d=\parallel P_a - P_b\parallel\).

-

Measurements of angle The angle of \(P_aP_bP_c\) is calculated as \(\alpha = \arccos \left( \frac{(P_a-P_b)\cdot (P_c-P_b)}{\parallel P_a-P_b\parallel \cdot \parallel P_c-P_b \parallel }\right)\). Noted that in alignment with the convention of foot measurements, angles larger than 90 degrees will be converted to \(\pi -\alpha\).

-

Measurements on manifold In this research, we focused on two types of manifold measurements: circumference passing 2 landmarks and circumference passing 1 landmarks. Since geodesic distance estimation on a discrete mesh could be unstable and inaccurate due to noise and discretization error, we define the circumference as the boundary length of the intersection of a plane and the foot mesh. Since neither 2 points nor 1 point can determine a plane, we append directional constraints to the plane:

-

1.

Circumference passing \({P}_a,{P}_b\): a preset tangent vector t is used as the directional constraints. Then the normal vector can be calculated as \(n=P_a-P_b\times t\). With \(P_a\) as the origin, the plane is defined as \(n\cdot x - P_a=0\), which is then used to crop the mesh and calculate the boundary length as circumference.

-

2.

Circumference passing \({P}_a\): a preset normal vector n is used as the directional constraints. With \(P_a\) as the origin, the plane is defined as \(n\cdot x - P_a=0\), which is then used to crop the mesh and calculate the boundary length as circumference.

-

1.

As referred to Table 1, the mean absolute error (MAE) of most of the foot measurements were within 10mm, except girths and foot length.

More formally, we concatenate the two features and output the class scores using a multi-layer perception (MLP):

where \(F_\text {ext}\) is the external features and p is the output scores for different types.

Validation of model

To evaluate the generalization capability and performance of our proposed model and traditional models for foot type classification, we conducted a 5-fold cross-validation that the dataset is divided into 5 equal folds without an imbalanced class occurring. The model was trained and validated five times, in which \(80\%\) of the 3D scan data was input for training and \(20\%\) for validation. Each iteration used a different fold (data not used for training) as the validation set and the remaining four folds were combined as the training set. This process was repeated until each fold has been used once as the validation set. The performance of each classifier was evaluated using the confusion matrices. For each confusion matrix, the row and the column show the instances of the actual class and predicted class respectively. Six metrics and accuracy were used for evaluating the performance of different models, including precision macro, precision micro, recall macro, recall micro, f1 macro and f1 micro . The 5-fold cross-validation was performed over seven models for comparison, including traditional machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machine (SVM), ensemble methods like RandomForest32 and XGBoost33, a gradient boosting framework like LightGBM34, a graph-based learning approach with Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) like Dynamic Graph CNN, a deep learning method specialized for point cloud data PointNet++, and our novel geometric deep learning approach like DiffusionNet with a Self-Attention mechanism.

Results

Quantitative evaluation

The feet of the diabetic patients in this study have been successfully classified into six types by using our proposed model, including SML, MWH and LNM types for female, and LMH, SWM and MNL types for male. For females, shorter feet are more likely to be flat (SML type: short lateral ball length, medium ball width and low instep height), while longer feet tend to have narrow ball breadth with medium instep height (LNM type). For males, shorter feet are more often voluminous (SWM type: short lateral ball length, wider ball width and medium instep height), while longer feet tend to have highest instep height with medium ball breadth (LMH type).

We evaluate our method with traditional machine learning approaches, including SVM35, Random Forest32, XGBoost33 and LightGBM34, and deep learning approaches, including DGCNN26 and PointNet++23. Since traditional ML methods can not process 3D raw data directly, we only use external features as inputs. The experimental results presented in Tables 2 and Table 3 provide a comprehensive analysis of the performance with competing methods in classifying 3D foot types. The results report insights w.r.t. the efficiency of different machine learning and deep learning approaches, highlighting the superiority of our proposed method.

Table 2 shows precision scores, recall scores and F1 scores of our proposed method and baseline methods using micro and macro average protocols respectively. The proposed model, utilizing of DiffusionNet with a self-attention mechanism, consistently outperforms other models across all metrics. Our method demonstrates precision scores, recall scores and F1 scores of over 0.8, indicating that it is highly accurate in both identifying the correct foot types without much error and in recalling most of the instances correctly. Besides, the standard deviation values of these metrics suggests that the model’s performance is consistently low across different folds of the cross-validation, indicating stability and robustness in its predictive capabilities.

Table 3 illustrates the accuracy scores of our proposed method and baseline methods. The proposed model achieves a mean accuracy of \(82.9\%\), which is significantly higher than competing methods. This lead is substantial, especially when compared to competing deep learning models, e.g. DGCNN and PointNet++. Besides, other traditional machine learning models and DGCNN show a wider standard deviation in their accuracy, indicating higher instabilities in performance, which is due to their inability to handle the complexity and variability in 3D foot shape data as effectively as our proposed model.

In a nutshell, the experimental results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of novel components in classifying 3D foot types. The high accuracy suggests the reliability of our proposed method in classifying foot types, which is crucial for applications in medical diagnostics and personalized footwear design. Besides, the consistency across different experimental folds implies that our model is robust and generalizes well to novel instances.

Confusion matrix

Figure 3 shows the confusion matrices of five-fold cross-validation for seven models. Only \(4-10\) samples (mean: \(8 \pm 2\)) were misclassified from the first fold to the fifth fold by using our proposed model, followed by \(7-13\) samples (mean: \(10 \pm 2\)) when using XGBoost, by \(8-15\) samples (mean: \(11 \pm 2\)) for LightGBM and by \(6-16\) samples (mean: \(12 \pm 3\)) for SVM. DGCNN and PointNet++ had a poorer performance for foot type classification that \(31-41\) samples (mean: \(35 \pm 4\)) and \(32-36\) (mean: \(35 \pm 1\)) samples were misclassified respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed to use DiffusionNet that incorporated a self-attention mechanism and external features for the 3D foot type classification task, which outperforms all the comparable models and allows reaching an average accuracy of over \(82\%\). This result proved that our proposed model could extract the most discriminative features and effectively classify six types of diabetic feet using 3D foot images. It could be due to the specialized architecture of DiffusionNet that is designed to tackle the unique challenges of processing and classifying 3D data. As the foot is relatively small and complex when compared to other parts of the human body, DiffusionNet can capture complex, non-linear and spatial relationships of both point cloud and graph-structured data, which is crucial for understanding the shape and structure of 3D objects like feet. It can also capture fine details and nuances of 3D shapes that the other more general-purpose models might overlook, like DGCNN and PointNet++. This indicated that DiffusionNet is effective and applicable for classifying small 3D objects, especially for feet. Noise and variations in the data are commonly found in 3D scans, the better classification performance might also indicate that DiffusionNet can be more robust to overcome the limitations of 3D scans. The favourable results of DiffusionNet can be also attributed to the incorporation of Self-Attention mechanism that allows the model to focus on relevant features within the input data, significantly enhancing its classification capabilities.

Although the classification performances of SVM, XGBoost and LightGBM were close to DiffusionNet, they require significant preprocessing and predefined features to handle and extract features from 3D point clouds effectively. This manual feature engineering process can be labour-intensive and may result in relevant information being missed from the dataset. In contrast, DiffusionNet can automatically learn and extract complex features from raw point cloud data without the need for manual feature engineering. In addition, SVM, XGBoost and LightGBM often require separate steps for feature extraction and classification. DiffusionNet allows for end-to-end learning that the model can be trained directly on raw data to produce classification outcomes, optimizing the entire pipeline in foot type classification for better performance and efficiency.

To classify feet as either normal, healthy or diabetic foot, traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches have utilised images of wound, foot skin and thermal images, achieving the accuracy rates ranging from \(96\%\) to \(99\%\)36,37,38,39. Our approach to analyse foot types of diabetic patients by using 3D foot images provides an efficient and innovative perspective for understanding the unique shape and characteristics of diabetic feet. This method allows for more precise adjustments to meet the specific needs of patients. Accurate classification of foot types is crucial for a variety of practical applications, offering benefits across multiple fields, from improving individual comfort and performance to preventing injuries, enhancing the sizing system for the industry and facilitating the development and design of orthotic footwear and insoles for effective diagnosis and treatments in medical filed.

Although our proposed model achieved the best performance in accuracy and other metrics for the classification of 3D foot type as compared to different conventional models, improvement could be made to further enhance the accuracy of the model by increasing the sample size and diversity of the training dataset to cover more variations in foot types for better generalizability. Improvements could be also carried out for model architecture to stabilize the performance, such as hyperparameter tuning, layer enhancements and feature engineering.

Conclusion

In this work, we proposed to use DiffusionNet that incorporated a self-attention mechanism and external features to classify the diabetic foot into six types from 3D foot images, which resulted in a satisfactory performance that capturing the nuances of the highly complexity of 3D foot shapes when compared to conventional machine and deep learning models. With the use of our proposed model, the process of customization can be facilitated for both the footwear industry and health settings to obtain a more optimal outcome to meet the actual needs and comfort of diabetic patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alazzawi, S., Sukeik, M., King, D. & Vemulapalli, K. Foot and ankle history and clinical examination: A guide to everyday practice. World J. Orthop. 8, 21 (2017).

Saghazadeh, M., Kitano, N. & Okura, T. Gender differences of foot characteristics in older Japanese adults using a 3d foot scanner. J. Foot Ankle Res. 8, 1–7 (2015).

Xu, M. Foot type classification for Chinese children and adolescents. Kinesiology 51, 127–132 (2019).

Chae, J., Kang, Y.-J. & Noh, Y. A deep-learning approach for foot-type classification using heterogeneous pressure data. Sensors 20, 4481 (2020).

Stanković, K., Huysmans, T., Danckaers, F., Sijbers, J. & Booth, B. G. Subject-specific identification of three dimensional foot shape deviations using statistical shape analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 151, 113372 (2020).

Tantisiriwat, N. & Janchai, S. Common foot problems in diabetic foot clinic. Med. J. Med. Assoc. Thailand 91, 1097 (2008).

Tang, U. H., Siegenthaler, J., Hagberg, K., Karlsson, J. & Tranberg, R. Foot anthropometrics in individuals with diabetes compared with the general Swedish population: Implications for shoe design. Foot Ankle Online J. 10, 1 (2017).

Razeghi, M. & Batt, M. E. Foot type classification: A critical review of current methods. Gait Posture 15, 282–291 (2002).

Lee, Y.-C. & Wang, M.-J. Taiwanese adult foot shape classification using 3d scanning data. Ergonomics 58, 513–523 (2015).

Alcacer, A., Epifanio, I., Ibáñez, M. V., Simó, A. & Ballester, A. A data-driven classification of 3d foot types by archetypal shapes based on landmarks. PLoS ONE 15, e0228016 (2020).

Mei, Z. et al. Foot type classification using sensor-enabled footwear and 1d-cnn. Measurement 165, 108184 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. A deep learning method for foot-type classification using plantar pressure images. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1239246 (2023).

Jertec, A. et al. On using pointnet architecture for human body segmentation. In 2019 11th International Symposium on Image and Signal Processing and Analysis (ISPA) 253–257 (IEEE, 2019).

Wang, H., Wu, Z. & Zhao, X. Surface and underwater human pose recognition based on temporal 3d point cloud deep learning. Sci. Rep. 14, 55 (2024).

Qi, C. R., Su, H., Mo, K. & Guibas, L. J. Pointnet: Deep learning on point sets for 3d classification and segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 652–660 (2017).

Sharp, N., Attaiki, S., Crane, K. & Ovsjanikov, M. Diffusionnet: Discretization agnostic learning on surfaces. ACM Trans. Graph. 41, 1–16 (2022).

Su, H., Maji, S., Kalogerakis, E. & Learned-Miller, E. Multi-view convolutional neural networks for 3d shape recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 945–953 (2015).

Feng, Y. et al. Group-view convolutional neural networks for 3d shape recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 264–272.

Gao, Z., Li, Y. & Wan, S. Exploring deep learning for view-based 3d model retrieval. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 16, 1–21 (2020).

Maturana, D. & Scherer, S. Voxnet: A 3d convolutional neural network for real-time object recognition. In 2015 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS) 922–928 (IEEE, 2015).

Zhou, Y. & Tuzel, O. Voxelnet: End-to-end learning for point cloud based 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4490–4499 (2018).

Wu, Z. et al. 3d shapenets: A deep representation for volumetric shapes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1912–1920 (2015).

Qi, C. R., Yi, L., Su, H. & Guibas, L. J. Pointnet++: Deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Pointcnn: Convolution on x-transformed points. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31 (2018).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Dynamic graph cnn for learning on point clouds. ACM Trans. Graph. 38, 1–12 (2019).

Lai, B. H., Lim, K. H. & Yii, A. Z. S. Graph convolutional network using self-attention module in point cloud classification. In 2023 International Conference on Digital Applications, Transformation & Economy (ICDATE) 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Sedaghat, N., Zolfaghari, M., Amiri, E. & Brox, T. Orientation-boosted voxel nets for 3d object recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1604.03351 (2016).

Smirnov, D. & Solomon, J. Hodgenet: Learning spectral geometry on triangle meshes. ACM Trans. Graph. 40, 1–11 (2021).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (2017).

Zhang, L.-Y., Yick, K.-L., Yue, M.-J., Yip, J. & Ng, S.-P. An exploratory study of dynamic foot shape measurements with 4d scanning system. Sci. Rep. 13, 8628 (2023).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition 1, 278–282 (1995) (IEEE).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (2016).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Hearst, M. A., Dumais, S. T., Osuna, E., Platt, J. & Scholkopf, B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Appl. 13, 18–28 (1998).

Harahap, M. et al. Classification of diabetic foot ulcer using convolutional neural network (cnn) in diabetic patients. J. Infotel 14, 196–202 (2022).

Thotad, P. N., Bharamagoudar, G. R. & Anami, B. S. Diabetic foot ulcer detection using deep learning approaches. Sens. Int. 4, 100210 (2023).

Goyal, M. et al. Dfunet: Convolutional neural networks for diabetic foot ulcer classification. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 4, 728–739 (2018).

Madhava, P. S. & Seema, V. Automated classification of the diabetic foot using comprehensive encoding and feature transform techniques. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 9, 747–753 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Laboratory for Artificial Intelligence in Design (Project Code: RP1-2) under the InnoHK Research Clusters, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (project code: WZ21), Hong Kong. The team also acknowledge the technical advice from Dr. Ali Asadipur, Royal College of Art in this collaborative study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L. conceived and designed the project, performed the experiment, conducted data processing and formal analysis, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript; Q.X. conducted formal analysis, constructed and validated the models, and wrote the manuscript; K.Y. supervised the project, reviewed and edited the manuscript; Q.L. constructed and validated the semi-automatic foot measurements model and wrote the methodology; L.Z. performed the experiment and data processing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Pl., Xiao, Qf., Yick, Kl. et al. A novel deep learning approach to classify 3D foot types of diabetic patients. Sci Rep 15, 13819 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98471-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98471-5