Abstract

This study was to compare the biomechanical outcomes of three ACL graft tibial fixations. Biomechanical testing was performed on 36 fresh porcine tibias and flexor profundus tendon divided into three groups: interference screw group (n = 12), internal brace group (n = 12) and combined group (n = 12). The samples underwent cyclic loading at 1 Hz at 50–250 N for 1000 cycles, following by load-to-failure testing (200 mm/min). The cyclic displacement, stiffness and ultimate failure loads were compared between the techniques. No sample failed during cyclic load test. The mean periodic displacement of the combined group (1.97 ± 0.32 mm)was significantly lower than both the internal brace group (2.85 ± 0.43 mm; p < 0.05) and interference screw group (2.48 ± 0.31 mm; p<0.05), but there was no significant difference between two fixation alone groups. The mean failure load of combined fixation (821.71 ± 78.39 N) was higher than that with interference screw (631.97 ± 109.96 N; p < 0.01) or internal brace (566.04 ± 57.68 N; P < 0.01) fixation alone. The combined group showed greater pullout stiffness (217.79 ± 36.66 N/mm) than both the interference screw (151.69 ± 30.28 N/mm; p < 0.01) and internal brace (162.94 ± 35.42 N/mm; p < 0.01) groups. Through biomechanical analysis, this study has demonstrated the feasibility of the soft tissue grafts fixed with internal brace and interference screw and its superiority in terms of higher ultimate failure load and stiffness compared to those fixed alone for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The findings from this study have significant implications for enhancing ACL reconstruction surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are one of the most common sports-related injuries in young, active patient populations1. Studies have reported that most patients obtain good to excellent results after ACL reconstruction (ACLR); however, there are still many debatable issues related to ACLR, such as graft selection, fixation choice, surgical techniques and rehabilitation after surgery2,3,4,5,6,7,8. The choice of fixation technique in ACLR remains a topic of debate2,5,6,7,8,9,10. The fixation used should be strong and stiff enough to allow for early, accelerated postoperative rehabilitation and biologic graft remodeling8,11,12,13,14. Scientific evidence indicates that graft tissue may lose its initial strength and stiffness during the graft revascularization phase, and early and accelerated recovery activity potentially leads to graft laxity15,16,17,18,19. Internal brace augmentation is a concept that assists ligament repair, and it is a bridging concept that involves using braided suture tape to reinforce ligament strength and act as a stabilizer after repair20. Internal bracing has been described in the knee for medial collateral ligament repair, ACL repair, ankle augmentation, etc21,22,23,24,25. Internal bracing in ACLR or ACL repair is a relatively new concept. The internal brace technique aims to improve graft strength with high-strength internal brace augmentation as a provisional scaffold20,26,27,28.

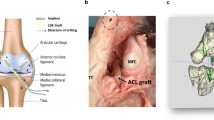

Internal brace technology is designed to improve the strength and stiffness of grafts during revascularization by using high-strength sutures as temporary scaffolds. Because the new high-strength sutures incorporate polyethylene, they provide sufficient strength and mechanical properties for the sutures9. The new polyblend sutures appear to have better mechanical properties than conventional sutures; the strength of a 1-strand No. 2 ULTRABRAID suture is approximately 250–290 N9. Theoretically, this internal brace increases the strength and stiffness of the ACL soft tissue graft to increase the initial stability of interference screw fixation (Fig. 1).

The purpose of this study was to compare the time zero biomechanical properties of 3 graft fixation techniques (interference screw, the internal brace, interference screw and the internal brace combined fixation) within the tibial tunnel in ACL/reconstruction. Our hypothesis was that combined fixation would result in a greater load to failure and higher stiffness than interference screws alone in the tibial tunnel when tested ex vivo in porcine bone.

Results

Cyclic load testing

No samples failed after 1000 cycles. The mean displacement was 2.48 ± 0.31 mm in the interference screw group, 2.85 ± 0.43 mm in the internal brace group, and 1.98 ± 0.32 mm in the combined group after 1000 cycles (Table 1). The combined group had significantly less displacement than the internal brace alone group (p < 0.05) and interference screw group (p < 0.05), but there was no significant difference between the internal brace group and the interference screw group.

Load-to-failure testing

The mean load to failure was highest in the combined group. The average load to failure was 821.71 ± 78.39 N for combined fixation, which was higher than that for interference screw fixation (631.97 ± 109.96 N; p < 0.05) and internal brace fixation (566.04 ± 57.69 N; p < 0.05). The difference was not statistically significant for interference screw or internal brace fixation alone (p > 0.05).

The combined group showed significantly higher pullout stiffness (217.79 ± 36.66 N/mm) than either the interference screw (151.69 ± 30.28 N/mm; p < 0.05) or internal brace (162.94 ± 35.42 N/mm; p < 0.05) group, but there was no significant difference between the internal brace group and the interference screw group (Table 1).

The modes of failure for the soft tissue interference screw samples were graft slipping past the screw in 10 cases and graft rupture in 2 cases. The failure mode in the internal brace group was suture breakage in 5 cases and anchor rupture on the tibial side in 7 cases. The modes of failure for the soft tissue in the combined group were suture breaking in the internal brace (n = 3), anchor breakage (graft slippage outside of the anchor; n = 4), anchor pullout (n = 4) and graft rupture (n = 1).

Discussion

In this study, we utilized a porcine tibiae model and compared the mechanical properties of screw interference fixation with and without the addition of an internal brace construct and we found that the addition of an internal brace construct during ACL reconstruction improves fixation strength and stiffness at time zero.

In our study, we found that combined internal brace fixation of soft tissue ACL grafts resulted in a significantly greater failure load and stiffness than interference screw or internal brace fixation alone when tested ex vivo in porcine bone. The grafts in the interference screw group are firmly secured to the inner wall of the tunnel through extrusion pressure exerted by the interference screw. With the addition of an internal brace, the graft, interface screw, and anchor form a cohesive unit that not only enhances initial stability but also ensures long-term support. As force intensifies, the interference screw primarily bears the initial load; however, as it begins to loosen, the internal brace and anchor gradually assume most of this responsibility. Simultaneously, the presence of an internal brace provides more uniform force distribution for the graft compared to solely relying on an interference screw. Our results support our hypothesis that adding an internal brace improves the ultimate failure load and stiffness compared with interference screw or internal brace fixation alone at time zero.

The present study evaluated one augmented fixation method that involved several high-strength sutures as internal brace augmentation in ACLR. Smith et al. introduced a technique modification with allograft ACLR utilizing internal brace augmentation27. This construction theoretically adds strength to the biomechanical properties of the ACL graft through the addition of tape but maintains the other properties of a natural graft. The major advantage of internal brace augmentation is that it protects the soft tissue graft during the revascularization and remodeling phase29. Smith PA adopted independent suture tape internal brace reinforcement of bone-patellar tendon-bone allografts in an ACLR laboratory model28. They found that suture tape internal bracing in bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft ACLR decreases cyclic displacement during experimental testing. Saper et al. also introduced a technique modification with independent suture tape reinforcement during all soft tissue quadriceps tendon autograft ACLR23. Several advantages of ACLR with internal brace augmentation are independent tensioning from the graft, protection of the graft during the healing process, accelerated rehabilitation, and a small diameter. However, no clinical data or biomechanical data were reported in Smith PA and Saper et al.23,27. Adding suture tape, it can be assumed that the additional reinforcement already strengthens the construct. Therefore, it can be concluded that the suture tape appears to be a “safety belt”, which becomes more dominant when the graft is exposed to higher loads, where it demonstrates more plastic deformation26. We tested our 3 fixation groups under cyclic loading and load-to-failure testing to mimic the repetitive loading that the reconstructed ACL experiences during early aggressive postoperative rehabilitation and catastrophic failure due to trauma. We found that augmented fixation of grafts with internal braces yielded a significantly greater failure load and higher stiffness than interference screw fixation alone. This biomechanical finding suggests that augmented tibial fixation in soft tissue ACLR may be of clinical benefit. In several studies, ACL forces were calculated as being near 450 N during daily exercise30. In our study, all three fixations survived the ultimate failure load criterion (450 N), were stronger than the 303 N reported as necessary for early rehabilitation and ambulation following ACLR30 and exceeded the acceptable levels for clinical application (> 500 N).

There are some studies supporting augmented ACLR or ACL repair31,32. Bachmaier et al.21 pointed out that internal bracing resulted in improved stabilization for ACL repair. Internal bracing had a crucial role in improving the potential stability of ACL repair at loads occurring during normal daily activity. The added strength of the internal brace allowed for reduced peak loads on the repaired ACL as well as restriction of gap formation to less than 3 mm at loads up to 350 N. Internal brace improvements in the mechanical characteristics of current ACL repairs enable reduced gap formation and allow for early range of motion and accelerated rehabilitation. Bachmaier et al.29 also compared the dynamic elongation, stiffness, and ultimate failure load of samples with small-diameter soft tissue grafts for ACLR with and without high-strength suture tape reinforcement. They found that independent suture tape reinforcement of soft tissue grafts in ACLR leads to significantly reduced elongation and a higher ultimate failure load without stress shielding the soft tissue graft. During early rehabilitation, the internal brace theoretically also protects the repaired ligament during the accelerated rehabilitation process27,28,33. The rationale behind the use of internal brace system fixation is to provide “independent” load-sharing fixation that improves the structural properties of the primary fixation with interference screws. The internal brace can also augment small-diameter autografts or provide additional support in a revision ACLR situation.

The novel internal brace technique for ACLR at the tibial site offers several potential advantages. (1) The ultimate load is higher. This internal brace augmentation technique uses No. 2 high-strength sutures (Smith and Nephew) for internal brace augmentation. The ultimate failure load of the internal brace was approximately 566.04 ± 57.68 N in our study, which exceeds 500 N. (2) The internal brace contributes to the creation of an “independent” stable system during biological healing, protects the graft and allows for accelerated rehabilitation. Scientific evidence indicates that most graft tissue loses a considerable amount of its initial strength and stiffness during the early rehabilitation period33,34. Through the addition of an internal brace, the reconstructed ACL could be enhanced to minimize tissue elongation and prevent even further loss of tension during the revascularization and remodeling phase, potentially minimizing ACL allograft retention.

There are some limitations in our study. (1) This study used a porcine model instead of young human cadaveric knees; however, because of its availability and because the structural and material properties of porcine tissue are similar to those of the tissue of young humans, we decided to perform our study on a widely used porcine model35,36. (2) This biomechanical study focused on time-zero outcomes only; these tests were performed with nonphysiologic force, creating only worst-case scenarios. (3) We could not study the healing process of the graft fixed to the bone over time, and no data exist regarding clinical outcomes. (4) There may be possible stress shielding of the graft and potential for over constraining the joint clinically. Therefore, we should fix the ACL on the tibia first in full hyperextension and then fix the internal brace on the tibia with a Swive lock with a knotless anchor. Both fixed with 80 N of force was maintained with a pulley system. (5) Further clinical studies should be conducted to determine whether this technique results in enough strength and stiffness to allow for early accelerated postoperative rehabilitation; the clinical effect of our internal brace technique is still a matter of further research.

This study showed that the addition of an internal brace yielded a significantly higher load to failure than an interference screw alone. Further in vivo studies are essential for validating our findings on grafts augmented with internal bracing.

Methods

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University (KT2020120). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The porcine tibia and tendons used in this study were all derived from the autopsy of porcine cadavers to reduce the injury and pain to the animals. Both tibias of the hogs are operated to reduce the number of hogs needed. A porcine model was chosen for this study; porcine tibias and porcine flexor profundus tendons were used because of previously reported biomechanical properties similar to those of young adult human knees10,35 and because the availability of young human cadavers for biomechanical testing is limited in our country. In this study, a total of thirty-six fresh-frozen porcine tibias and 36 porcine flexor profundus tendons (80–90 kg, 12–16 months old) were collected from local slaughterhouses. The soft tissue and muscles were dissected completely, leaving the tibia and ACL footprint intact. All tibias and tendons were stored at -20 °C for 7 days. Prior to testing, all specimens were thawed at 4 °C for 24 h, and all of the specimens underwent 1 freeze-thaw cycle before biomechanical testing. The specimens were regularly moistened with 0.9% saline during biomechanical testing36.

Sample Preparation

The bone mineral density (BMD) of the proximal porcine tibias was assessed using quantitative CT (QCT). The region of interest (ROI) was selected: The proximal tibial defect of porcine was concentrated on a cube containing cartilage with a radius of 10 mm. The mean BMD was 1.22 ± 0.41 (g/cm3) in the interference screw group, 1.25 ± 0.32 (g/cm3) in the internal brace group, and 1.28 ± 0.52 (g/cm3) in the combined group. There was no significant difference in BMD among the three groups (p > 0.05). The tibias were randomly assigned to three groups (Fig. 2): the internal brace group (n = 12), the interference screw group (n = 12) and the combined group (n = 12). All surgical procedures were performed by the senior author (Zhang). To prepare the single-looped graft on the table, thread the porcine tendon through the 20 mm closed-loop ENDOBUTTON (Smith and Nephew) and fold it in half, thinning it to 8 mm in diameter. Two ULTRABRAID sutures (Smith and Nephew) were used to sew 3 cm of both ends of each tendon using a crisscrossing stitch (Fig. 3). The tibial guide pin was positioned at the center of the ACL footprint. The tibial tunnel (40 mm in length) was prepared with a reamer (diameter 8 mm). The graft tendon was then placed through the tibial tunnel using a beath pin. A 20-mm closed-loop ENDOBUTTON (Smith and Nephew) was held in a clamp/device (Fig. 4). ENDOBUTTON was used in all samples in all groups to simulate femoral site fixation.

Sawbone model demonstrating the internal brace fixation technique. (A,B) The two ends of the tendons and the two ends of the 4-strand high-strength sutures were combined in advance. A graft link sample with a Button loop and internal brace. (C,D) The soft tissue graft and internal brace were pulled into the tibial tunnel. (E) A 4-mm pin was drilled 1 cm distal to the tibial tunnel. (E) The sutures were passed to the lateral side with an eyelet-passing pin. (F) The 4-strand high-strength sutures were fixed at the tibia with a 4.5 mm × 20-mm anchor (FOOTPRINT ULTRA PK suture anchor; Smith and Nephew). The anchor was placed 10 mm distal to the tibial tunnel. The sutures were tied at the anchor.

Interference screw group

In the interference screw group, a 9 × 20-mm titanium interference screw (Smith and Nephew) was used to fix the soft tissue graft at the tibial tunnel. Screw all interference screws into the tibial tunnel until the ends of the screws are flush with the entrance of the tibial tunnel. The tendon was tensioned at 80 N of force using a pulley system.

Internal Brace group

For internal brace fixation (Figs. 1, 2 and 3), two ULTRABRAID sutures (Smith and Nephew) were passed through a fixed loop on the suspensory device (15 mm ENDOBUTTON, Smith and Nephew), with the graft passing through this same device; the 4 free ends of the tape were attached on the tibial side. A 4.5 mm drill hole was made 1 cm distal to the tibial tunnel, and then the two ends of the suture tape for the internal brace were fixed with a FOOTPRINT ULTRA PK suture anchor (4.5 mm, Smith and Nephew), while 80 N of force was maintained with a pulley system through the proximal end of the graft and the internal brace.

Combined group

In the combined fixation group, the internal brace was first fixed. A 4.5 mm drill hole was made 1 cm distal to the tibial tunnel and fixed with a FOOTPRINT ULTRA PK suture anchor (Smith and Nephew), while 80 N of force was maintained with a pulley system. Next, while maintaining traction on the soft graft with a pulley system (80 N), the soft graft was fixated with a 9 × 20-mm titanium interference screw at the tibial tunnel. The screw advanced the same distance from the tibial opening in the tunnel as the interference screw group.

Biomechanical testing

The samples were then fixed in a custom jig and transfixed with a threaded bolt (Fig. 4)19,36. The proximal graft was fixed to a bar attached to the base of the material testing machine. The custom jig was placed on the testing machine, and the tendinous portion of the graft was pulled into the tibial tunnel so that the tensile force was parallel to the tibial tunnel. The length between the articular surface of the tibial plateau and the clamp was 40 mm.

The samples for the 3 fixation methods underwent cyclic loading and load-to-failure testing under tensile force in line with the tibial tunnel, in accordance with the “worst-case scenario” for graft testing. All biomechanical tests were administered using an Electroplus E3000 unit (Instron, High Wycombe, UK). The samples were preconditioned at 50 N at 1 Hz for 10 cycles, followed by cycling from 50 to 250 N at 1 Hz for 1000 cycles. After 1000 cycles, a load-to-failure test was conducted at 200 mm/min19,30. In the cyclic loading experiment and loading to failure experiment, if the sample fails, the force recorded by the test machine will suddenly change and decrease rapidly, and even stop operation due to the displacement protection of the instrument itself. The displacement after the cycling test, ultimate failure load, stiffness and mode of failure were recorded for each sample. The magnitude of graft displacement was defined as the distance between the lines: the grafts were marked with ink at the tunnel exit points (the exit of the tunnel at the articular surface) and again after cyclic tensile loading, and the distance was measured with digital calipers. The pullout stiffness (in N/mm) was calculated as the slope of the linear portion of the load-elongation curve. When the ultimate failure load occurs, the model fails. In the load-displacement diagram, the slope changes significantly, and the slope of the image (average slope) before the failure is the pullout stiffness.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The normality test of the three parameters in this experiment (Q–Q graph method) shows that all parameters obey normal distribution. The single factor ANOVA test was used to test the homogeneity of variance, and each count data was consistent with the homogeneity of variance. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine differences among the 3 groups. The P value was set to 0.05.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Beynnon, B. D. et al. Accelerated versus nonaccelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective, randomized, double-blind investigation evaluating knee joint laxity using Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 39, 2536–2548 (2011).

Aga, C. et al. Biomechanical comparison of interference screws and combination screw and sheath devices for soft tissue anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on the tibial side. Am. J. Sports Med. 41, 841–848 (2013).

Barrett, G. R., Luber, K., Replogle, W. H. & Manley, J. L. Allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the young, active patient: Tegner activity level and failure rate. Arthroscopy 26, 1593–1601 (2010).

Batty, L. M. et al. Synthetic devices for reconstructive surgery of the cruciate ligaments: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 31, 957–968 (2015).

Brand, J. Jr., Weiler, A., Caborn, D. N., Brown, C. H. Jr. & Johnson, D. L. Graft fixation in cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am. J. Sports Med. 28, 761–774 (2000).

Harvey, A., Thomas, N. P. & Amis, A. A. Fixation of the graft in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 87, 593–603 (2005).

Harvey, A. R., Thomas, N. P. & Amis, A. A. The effect of screw length and position on fixation of four-stranded hamstring grafts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 10, 97–102 (2003).

Lee, J. J. et al. Is supplementary fixation necessary in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions? Am. J. Sports Med. 39, 360–365 (2011).

Scheffler, S. U., Südkamp, N. P., Göckenjan, A., Hoffmann, R. F. & Weiler, A. Biomechanical comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon graft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction techniques: The impact of fixation level and fixation method under Cyclic loading. Arthroscopy 18, 304–315 (2002).

Wüst, D. M., Meyer, D. C., Favre, P. & Gerber, C. Mechanical and handling properties of braided polyblend polyethylene sutures in comparison to braided polyester and monofilament polydioxanone sutures. Arthroscopy 22, 1146–1153 (2006).

Ekdahl, M., Wang, J. H., Ronga, M. & Fu, F. H. Graft healing in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 16, 935–947 (2008).

van Grinsven, S., van Cingel, R. E., Holla, C. J. & van Loon, C. J. Evidence-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 18, 1128–1144 (2010).

Arnold, M. P. et al. The remains of anterior cruciate ligament graft tension after cyclic knee motion. Am. J. Sports Med. 33, 536–542 (2005).

Duchman, K. R., Lynch, T. S. & Spindler, K. P. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament surgery: Who gets what and why? Clin. Sports Med. 36, 25–33 (2017).

Kousa, P., Järvinen, T. L., Vihavainen, M., Kannus, P. & Järvinen, M. The fixation strength of six hamstring tendon graft fixation devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part I: Femoral site. Am. J. Sports Med. 31, 174–181 (2003).

Kousa, P., Järvinen, T. L., Vihavainen, M., Kannus, P. & Järvinen, M. The fixation strength of six hamstring tendon graft fixation devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part II: Tibial site. Am. J. Sports Med. 31, 182–188 (2003).

Lin, K. M., Boyle, C., Marom, N. & Marx, R. G. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 28, 41–48 (2020).

Nakano, H. et al. Interference screw fixation of doubled flexor tendon graft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction—Biomechanical evaluation with cyclic elongation. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol Avon) 15, 188–195 (2000).

Walsh, M. P., Wijdicks, C. A., Parker, J. B., Hapa, O. & LaPrade, R. F. A comparison between a retrograde interference screw, suture button, and combined fixation on the tibial side in an all-inside anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A biomechanical study in a porcine model. Am. J. Sports Med. 37, 160–167 (2009).

Dabis, J. & Wilson, A. Repair and augmentation with internal Brace in the multiligament injured knee. Clin. Sports Med. 38, 275–283 (2019).

Bachmaier, S. et al. Treatment of acute proximal anterior cruciate ligament tears-part 2: The role of internal bracing on gap formation and stabilization of repair techniques. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 8, 2325967119897423 (2020).

Lubowitz, J. H., MacKay, G. & Gilmer, B. Knee medial collateral ligament and posteromedial corner anatomic repair with internal bracing. Arthrosc. Tech. 3, e505–508 (2014).

Saper, M. G. Quadriceps tendon autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with independent suture tape reinforcement. Arthrosc. Tech. 7, e1221–e1229 (2018).

Shelbourne, K. D. & Nitz, P. Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am. J. Sports Med. 18, 292–299 (1990).

van der List, J. P. & DiFelice, G. S. Primary repair of the medial collateral ligament with internal bracing. Arthrosc. Tech. 6, e933–e937 (2017).

Levy, B. A., Piepenbrink, M., Stuart, M. J. & Wijdicks, C. A. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with independent suture tape reinforcement: An in vitro biomechanical full construct study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 9, 2325967120981875 (2021).

Smith, P. A. & Bley, J. A. Allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction utilizing internal Brace augmentation. Arthrosc. Tech. 5, e1143–e1147 (2016).

Smith, P. A., Bradley, J. P., Konicek, J., Bley, J. A. & Wijdicks, C. A. Independent suture tape internal brace reinforcement of bone-patellar tendon-bone allografts: Biomechanical assessment in a full-ACL reconstruction laboratory model. J. Knee Surg. 33, 1047–1054 (2020).

Bachmaier, S., Smith, P. A., Bley, J. & Wijdicks, C. A. Independent suture tape reinforcement of small and standard diameter grafts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A biomechanical full construct model. Arthroscopy 34, 490–499 (2018).

Shelburne, K. B. & Pandy, M. G. A dynamic model of the knee and lower limb for simulating rising movements. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 5, 149–159 (2002).

Ebert, J. R. & Annear, P. T. ACL reconstruction using autologous hamstrings augmented with the ligament augmentation and reconstruction system provides good clinical scores, high levels of satisfaction and return to sport, and a low retear rate at 2 years. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 7, 2325967119879079 (2019).

Lubowitz, J. H. Editorial commentary: Synthetic ACL grafts are more important than clinical nonbelievers may realize. Arthroscopy 31, 969–970 (2015).

Wilson, W. T., Hopper, G. P., Byrne, P. A. & MacKay, G. M. Anterior cruciate ligament repair with internal brace ligament augmentation. Surg. Technol. Int. 29, 273–278 (2016).

Bottoni, C. R. et al. Autograft versus allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective, randomized clinical study with a minimum 10-year follow-up. Am. J. Sports Med. 43, 2501–2509 (2015).

Duan, M. Y., Sun, R., Zhuang, L. T. & Zhang, H. Z. Biomechanical evaluation of a novel transtibial posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using high-strength sutures in a porcine bone model. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 134, 2316–2321 (2021).

Sun, T. & Zhang, H. Biomechanical comparison of a novel tibial fixation technique versus interference screw fixation for ACL reconstruction using soft tissue grafts. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 9, 23259671211028559 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZHZ, CSQ and WJY performed the study and wrote the first manuscript. LWX analyzed the data. YJH, LYH, revised the manuscript. All the authors have given approval for the final version of the manuscript. All the authors agree to be account able for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Wang, J., You, J. et al. Internal brace augmentation in ACL reconstruction increases structural strength and stiffness: a biomechanical study in a porcine tibia model. Sci Rep 15, 33628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98491-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98491-1