Abstract

Landscape features have a profound impact on river water quality. However, its impact in subtropical hilly region is unclear. Here, water quality data from 15 catchments were obtained based on a typical subtropical hilly area, the upper Ganjiang River basin. The landscape features in the catchment and buffer zone were calculated, and its effects on river water quality were investigated using redundancy analysis (RDA) and multiple linear regression (MLR) model. Catchment landscape features were found to better explain overall water quality changes compared to buffer zone, and landscape features were found to explain water quality changes more in winter than in summer. Moreover, within the buffer zone, the percentage of grassland had the greatest impact on winter water quality (72.8%), while at the catchment scale, the aggregation index (AI) of grassland contributed the most to changes in winter water quality (31.6%). Nonparametric change-point analysis (nCPA) was used to identify thresholds of landscape features that lead to abrupt changes in water quality. It was found that river water quality can be improved when the percentage of grassland > 0.193%, the largest patch index (LPI) of forest > 7.48% at the buffer zone or the percentage of impervious surfaces < 2.92%, the AI of forest > 98.6% at the catchment scale. This study demonstrated the pivotal role in enhancing river water quality by implementing informed and effective landscape planning for conservation implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

River water quality has a profound impact on local drinking water safety, environmental health, and sustainable development1,2. Nevertheless, river water pollution remains ubiquitous, and water pollution from anthropogenic or non-anthropogenic causes has received widespread attention worldwide3,4. The landscape can affect the processes of transport, transformation, and release of pollutants in runoff5,6. In-depth understanding of landscape features is conducive to improving river water quality and promoting regional sustainable development.

Landscape features were usually quantified by landscape metrics7,8, which are divided into two main categories: landscape composition metrics and landscape configuration metrics. The former reflects the composition of the landscape, while the latter responds to the spatial layout and pattern of the landscape9,10. Several investigations have delved into the impacts of landscape features on river water quality, shedding light on their relationships11,12,13,14. Initially, related studies focused on impact of the percentage of land use on water quality15,16,17. Water quality is generally better in forest and grassland areas, which are less impacted by human activities, while areas frequently inhabited by humans, such as built-up and cultivated zones, tend to have poorer water quality18,19,20. Recently, there is a growing trend of research on the effects of the structure and configuration of landscapes on water quality21,22,23,24. For instance, Liu and Yang25 found that patch density and patch number in built-up areas of Shenzhen were the key landscape features driving water quality degradation. Geographic factors may play a non-negligible role in the process through which landscape features influence river water quality. It mainly refer to the geographic characteristics that affect the change of water quality, such as the topography, slope, elevation, etc., which have a great impact on the flow path of pollutants. Studies have shown that changes in water quality can be explained more by geographical factors than by landscape composition metrics26,27. This, in turn, leads to a significant variation in their influence on water quality. Therefore, further research is needed to fully understand the impacts of landscape features and geographical factors on river water quality to provide valuable insights for landscape planners.

Landscape features have significant spatial scale effects on river water quality11,12,27. In general, the spatial scale of a river is measured primarily through the riparian buffer zone and catchment scale28,29. To date, the issue of the scale at which landscape features affect water quality in rivers has been highly controversial. On the one hand, some studies found that at the catchment scale, landscape features have been found to better explain variations in river water quality compared to those within buffer zone27,30, Ding, et al.31 noted that at mountain catchment scale landscape features had an impact on water quality that was respectively 9.6% and 5.1% higher than that of the buffer zone. On the other hand, it has also been observed that landscape features within buffer zone provided a more nuanced understanding of overall changes in water quality than those at the catchment scale12,28. For instance, Wu and Lu26 reported that landscape features at the buffer zone explained 67.6% of the variation in water quality, which is 8.2% higher than at the catchment scale. In addition, there is also a neutral view that buffer zone and catchment are equally important14. Given this, the scale effect of landscape features on water quality needs to be further studied.

This study focuses on a typical subtropical hilly region—the upper reaches of the Ganjiang River basin, analyzing the scale and seasonal effects of landscape features on river water quality. It aims to: (1) identifying key landscape features that influence overall water quality in the river; (2) quantifying the extent to which key landscape features affect water quality; and (3) recognizing thresholds for abrupt changes in water quality due to key landscape features.

Materials and methods

Study area

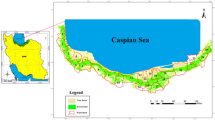

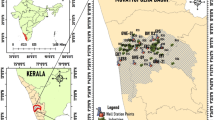

The upper reaches of the Ganjiang River Basin (25°55′-26°35′N, 113°45′-114°45′E) are located in southeastern China, in the southern part of Jiangxi Province, with most of the basin situated within Ganzhou City (Fig. 1). It borders Fujian Province to the east, Guangdong Province to the south, and Hunan Province to the west. The river network in the upper Ganjiang River Basin is well developed, primarily formed by the confluence of the Zhangjiang and Gongjiang Rivers, which ultimately flow into Poyang Lake. The Zhangjiang and Gongjiang River basins cover areas of approximately 7,683 km² and 2,259.4 km², with lengths of 199 km and 278 km, respectively. The region is characterized by a subtropical monsoon climate, with warm and humid conditions. The annual mean temperature ranges from 17 °C to 20 °C, with mild winters and hot, rainy summers. Annual precipitation is abundant, ranging from approximately 1,400 mm to 1,900 mm, with the rainy season concentrated between April and June, often leading to flooding events. The topography is dominated by mountains, hills, and basins, with mountainous and hilly terrain accounting for approximately 70% of the total area. Major mountain ranges include the Wuyi Mountains, Jiulian Mountains, and Dayu Mountains. The average elevation is approximately 300 m, with the highest peak, Qiyun Mountain, reaching an altitude of 2,061 m. The region exhibits a high forest coverage rate of 72%, serving as a crucial ecological barrier of national significance.

Sample sites and land use types in the study area (a); Sub-catchment scale, more information is presented in Fig. S1 in the supplementary information. (b); 100 m buffer zone (c). The maps were generated by ArcGIS 10.2 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/index). China’s administrative boundary vector data were obtained from the https://gadm.org/data.html. Catchment data are derived from https://www.hydrosheds.org/products/hydrobasins.

Acquisition of river water quality data

The water quality information for the 15 monitoring stations in the upstream of Ganjiang River (January, 2021 and July, 2021) were obtained from the National Surface Water Quality Monitoring Panel (NSWQMP) (Data is provided within the supplementary information file (Table S2)). To ensure that the data were seasonally representative, four days were selected for both January and July (one day per week was selected) and averaged for each water quality indicators. The selected water quality indicators in our study including: total phosphorus (TP, mg·L− 1), total nitrogen (TN, mg·L− 1), permanganate index (CODMn, mg·L− 1), chemical oxygen demand (COD, mg·L− 1), five-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5, mg·L− 1), and ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3-N, mg·L− 1). Information on the water quality indicators tested includes the following: TN was determined by ultraviolet spectrophotometry using alkaline potassium persulfate digestion (the lower limit of detection is 0.05 mg·L− 1), TP was determined by ammonium molybdate spectrophotometry (the lower limit of detection is 0.01 mg·L− 1), NH3-N was determined by Nano reagent colorimetric method (the lower limit of detection is 0.05 mg·L− 1), BOD5 was determined by dilution and inoculation method (the lower limit of detection is 2 mg·L− 1), COD was determined by the dichromate method (lower limit of detection was 0.05 mg·L− 1), and CODMn was determined by titration (range of detection was 0.5 to 4.5 mg·L− 1). The above indicators not only reflect the overall nutrient status of the water body, but also are the key indicators in China’s surface water quality standard, which are able to assess whether the water quality is up to the standard or not.

Selection of the spatial scale

The ability of landscape features to explain changes in water quality indicators has been controversial at the subbasin scale and buffer scale24,27,32. In this study, both catchment and buffer zone scales were considered in an attempt to further the argument. Only a 100 m buffer zone was established in this study, taking into account the experience of previous studies26,29 (Fig. 4).

Landscape features acquisition

In this study, catchment and river system data was derived from hydrosheds products (https://www.hydrosheds.org/products). Landscape features were analyzed using 30 m resolution land use data in 2021, who has five main types, namely cropland, forest, grassland, water, and impervious33. Here, only cropland, forest, grassland and impervious were considered, while water was not analyzed due to their lower percentages. The landscape features were calculated using FRAGSTATS V4.2 program, detailed information was shown in Table 1. The digital elevation model (DEM, the resolution of 30 m) data were obtained from a geospatial data cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/). Geographic factors including elevation, standard deviation of elevation (SDelevation), relief (maximum minus minimum value of elevation), slope, and standard deviation of slope (SDslope) were calculated by using ArcGIS 10.2 software.

Statistical analysis

To ensure the validity of our analysis, we conducted tests for normal distribution across all data. Additionally, t-tests was employed to scrutinize any significant differences in water quality indicators across different seasons, aiming for a nuanced understanding of seasonal variations. The Redundancy Analysis (RDA) as a tool for elucidating the intricate relationship between landscape features and water quality underscores its proven efficacy in this field of study6,29,31. Before the RDA analysis, the water quality indicators were analyzed for detrending correspondence analysis (DCA), and the length of all four axes was less than 3, indicating that RDA can be applied to this data. Monte Carlo replacement test was used to select key landscape features (P < 0.05)31. In this study, RDA was analyzed with CANOCO 5.0 software (Microcomputer Dynamics, Inc., USA). Multiple linear regression (MLR) for identifying the influence of key landscape features for each water quality indicators. Before analyzing the regression models, variance inflation factor (VIF < 10) was computed to reduce covariance among the key variables. To ensure the parsimony of our final models, backward Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) model comparisons was utilized in selecting multiple linear regression models. This approach facilitated the identification of models that are both concise and informative. All of the final models were selected based on having a ∆BIC value > 2, indicating a substantial improvement in model fit compared to alternative candidates34. Additionally, nonparametric change-point analysis (nCPA) was used to detect key points or ranges that lead to abrupt changes in individual water quality indicators, as detailed in the methodology described in Qian, et al.35. The above statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.1) except for RDA.

Results

Seasonal differences of water quality indicators

The seasonal variations in water quality indicators were depicted in Fig. 2. Overall, the concentrations of TN (S1, S2, S4, S6, S8, S9, S10, S11), NH3-N (S4, S5, S6, S11) and BOD5 (S3, S4, S5, S6, S8, S9, S10, S11, S13) were significantly elevated in winter compared to summer (P < 0.05). Conversely, the concentrations of CODMn (S1, S6, S7, S9, S10, S12, S13, S14) were significantly elevated in summer compared to winter (P < 0.05). The average concentrations of CODMn, COD, BOD5, NH3-N, and TP were recorded as 1.91 mg·L− 1, 8.22 mg·L− 1, 1.02 mg·L− 1, 0.13 mg·L− 1, and 0.05 mg·L− 1, respectively, all falling below the permissible limits set by the Class III national surface water quality standards (suitable for the secondary protection area, fish culture area and swimming area of the surface water source of centralized drinking water, and the water quality exceeding the tertiary standard is not suitable for human contact) stipulated by the National Environmental Protection Bureau (NEPB) in 2002. Nevertheless, the average TN concentration (1.56 mg·L− 1) exceeded the limit (< 1.0 mg·L− 1), especially in the winter (Fig. 2f).

Landscape features analysis

Indicators reflecting landscape features were measured at different spatial scales were presented in Table 2. Cropland and forest dominated significantly at the buffer zone and catchment scale. Yet the riparian zone exhibited a higher percentage of cropland compared to the catchment, while the opposite trend was observed for forest cover. The PD’s average values for the four land use types and geographic factors (except HI) at the riparian buffer zone were higher than those at the catchment scale. While the average values of AI, LPI and LSI for each land use type were higher at the catchment scale than at the buffer zone, except LPIgrass, LPIimp and LSIforest.

Influence of key landscape features on overall water quality indicators

The results of RDA were presented in Table 3; Fig. 3. Our findings indicated that in winter, the chosen key landscape features explained a substantial portion of water quality variations, ranging from 33.1 to 59.3%, surpassing the total explanatory ability observed in summer by 5.3–12.2%. Furthermore, these variables demonstrated a greater explanatory ability at the sub-catchment scale compared to the buffer zone (Table 3).

At the buffer zone, slope had the greatest contribution to water quality within the buffer zone in summer, contributing 46.9% and positively correlated with most water quality indicators, including TN, COD, BOD5, and NH3-N. However, the contribution of slope dropped significantly to only 21.8% in winter. Grassland emerged as the primary factor influencing water quality changes, and was negatively correlated with all water quality indicators in winter (Fig. 3a and b). LPIimp, AIimp and AIcrop were key landscape features in summer at the catchment scale, and their contributions were 48.3%, 48%, and 3.7%, respectively. The AIimp and LPIimp had negative correlations with most water quality indicators during the summer, while the opposite was true about AIcrop. The contributions of AIgrass, AIforest, Impervious and LPIcrop were more than 20%, with AIgrass exhibiting a negative correlation with water quality indicators, whereas AIforest, Impervious, and LPIcrop displayed positive correlations (Fig. 3c and d).

Influence of key landscape features on each water quality indicator

Upon discovering the substantial influence of key landscape features on overall water quality during winter through RDA, it was proceeded with an in-depth analysis employing MLR models (Table 4). This additional step aimed to scrutinize the specific influence of these landscape features on each water quality indicator in winter, providing a nuanced understanding of their relationships. At the buffer zone, grassland was negatively correlated with COD, BOD5, TP and TN in winter with coefficients of -4.68, -20.02, -0.17 and − 2.48, respectively. LPIforest was positively correlated with CODMn, BOD5, but negatively correlated with NH3-N. Furthermore, slope and slope: grassland were negatively correlated with BOD5. At the catchment scale, impervious was positively correlated with CODMn, NH3-N and TN, and they possessed the largest coefficients, which were 0.39, 0.91 and 1.06, respectively. LPIcrop was negatively correlated with NH3-N and TN. AIforest was positively correlated with COD and TP, AIgrass was negatively correlated with them.

The identification of abrupt change point

Identifying abrupt change point at which key landscape features lead to abrupt changes in pollutant concentrations in rivers is critical for water purification. Here, the cumulative abrupt change probability of key landscape features on the concentration of water quality in winter was analyzed at catchment scale and buffer zone (Fig. 4). In terms of buffer zone, the cumulative abrupt change probability for CODMn and NH3-N reached 100% when the values of LPIforest exceeded 5.47% and 7.48%, respectively. Moreover, the cumulative abrupt change probability of COD, BOD5, TP and TN could reach 100% when the value of grassland exceeded 0.193%, 0.171%, 0.16% and 0.11%, respectively. Therefore, the values of LPIforest more than 7.48% and grassland more than 0.193% at the buffer zone could promote water purification. For catchment scale, the cumulative abrupt change probability for CODMn, NH3-N and TN could reach 100% when the value of impervious exceeded 4.41%, 2.92% and 4.43%, respectively. The cumulative abrupt change probability for COD and TP could reach 100% when the value of AIforest exceeded 98.5% and 98.6%, respectively. In addition, the cumulative abrupt change probability of BOD5 could reach 100% when the value of immediate exceeded 58.7%.

Discussion

Impact of landscape features on river water quality

Surface runoff has been identified as an important pathway for nutrient and pollutant transport, which are strongly influenced by the surrounding landscape19,31. In general, the percentage of land use types affects water pollution loads to the catchment, while their specific structure and configuration affects the way nutrients enter the river36,37. In addition, increased forest cover is positively associated with improved river water quality, which may be attributed to the ability of the forest root system to absorb, sequester and retain pollutants23,38,39. Consistent findings were observed regarding the influence of LPI of forest on summer river water quality within the buffer zone. However, during winter, while LPI and AI of forest showed positive associations with certain water quality parameters (e.g., CODMn, BOD5), they exhibited a negative correlation solely with NH3-N (Fig. 3; Table 4). This may be due to the increase of dead leaves on the forest floor in winter, which results in a large amount of nutrients from humus entering the river as surface runoff. In contrast, the source of NH3-N in forests is mainly plant decomposition, which is slowed down by lower temperatures in winter, leading to the result that LPI of forest is only negatively correlated with NH3-N40. Patch density serves as an indicator of the fragmentation level within the study area, where a higher value signifies a greater degree of fragmentation among the patches10. In general, smaller patches have a lower capacity to intercept and absorb nonpoint source pollutants27. As shown in this study, PD of forest showed positive correlations with river water quality parameters, which suggested that the increased fragmentation of the landscape or patches led to a deterioration of river water quality. Grassland had the same important role as forests in trapping pollutants41,42. Grassland at the riparian buffer zone and AI of grassland at the catchment had negative correlations with most water quality indicators in the winter (Fig. 3; Table 4), illustrating their key role in improving river water quality, but when grassland is correlated with slope, their combined effect may contribute to increased BOD5 in rivers (Table 4), which requires special attention in hilly terrain. Cropland is an important source of nutrients or pollution to the river water quality11, similar results were presented in this study (LPIcrop and AIcrop). The negative impacts of impervious surfaces on river water quality are self-evident and well established26,27,32. Same effects of impervious surfaces on winter water quality in this study. However, the AI of impervious was negatively associated with summer water quality indicators, which may be due to the fact that the aggregation of impervious surfaces strengthens the management of pollutants in the area, reducing surface nutrients entering rivers through runoff43,44. Therefore, analyzing influence of landscape features on river water quality is beneficial in identifying potential strategies for purifying water quality through landscape modification.

Analysis of spatio-temporal effects

There is significant spatial heterogeneity in the landscape, so it is essential to analyze the effects of landscape features on water quality at different spatial scales26,28. Here, the explanatory ability of landscape features in accounting for spatial variations in water quality ranged from 27.8 to 59.3% (Table 3). Furthermore, the selected landscape features at the catchment scale had higher total explanatory rate than at the buffer zone. This may be because within the buffer zone, river water quality is more susceptible to geographical factors such as slope (Table 3). As for the whole basin, most areas are far away from the river, and the water quality is more affected by surface runoff, with the landscape playing an important role in this process. This also suggests, to some extent, that both buffer zone and catchment scales may require attention in terms of protecting river water quality. On the basis of this study, it is suggested to control impervious surface and farmland structure (LPI, AI) at basin scales, and pay attention to forest, grassland and slope structure (PD, LPI) in buffer zone (Table 3), so as to protect the water quality of the upper reaches of Ganjiang River.

Seasonal changes affect the landscape, especially forest, grassland and cropland in the subtropical monsoon climate zone. Consequently, the influence of the landscape features on water quality varies from season to season26,27,32. Contrary to numerous prior studies21,26, the effect of landscape features on water quality was notably more pronounced during winter. This is because the study area is hilly and has a high percentage of forest cover, which is more than 80%, and the high level of vegetation cover enhances the ability to intercept and absorb pollutants. And when the vegetation dies down in winter, its litter instead becomes an important source of nutrients for water quality.

Landscape management strategies

Here, nCPA was used to detect the thresholds of key landscape metrics leading to abrupt changes in individual water quality indicators during winter (Fig. 4). The results showed that grassland was the main landscape feature affecting COD, BOD5, TP and TN in riparian buffer zone, and its abrupt points were 0.193%, 0.171%, 0.16% and 0.11%, respectively. The LPI values of forest leading to abrupt changes in CODMn and NH3-N concentration were 5.47% and 7.48%, respectively. This suggested that the percentage of grassland should be controlled to be higher than 0.193% as well as the LPI value of forest should be greater than 7.48% to improve river water quality. At the catchment scale, impervious surface was the key impact landscape feature for CODMn, NH3-N, and TN with 4.41%, 2.92%, and 4.43% of the abrupt points, respectively. The AI of forest resulted in abrupt points of 98.5% and 98.6% for COD and TP concentrations, respectively. This suggested that impervious surface should not exceeded 2.92% and AI of forest should exceeded 98.6% to benefit winter river water quality.

Conclusion

In summary, the influence of landscape features on the water quality of the upper reaches of Ganjiang River was examined in this study. It was found that landscape features at the catchment scale explained water quality changes better than buffer zone, with a greater influence observed in winter than in summer. At the buffer zone, the percentage of grassland (72.8%) had the greatest impact on winter water quality, while at the catchment scale, the AI of grassland (31.6%) was the highest contributor to winter water quality change. In addition, thresholds where landscape features lead to abrupt changes in river water quality were detected, and the thresholds for impervious and AIforest occurred at 2.93% and 98.6% at the catchment scale, respectively. This study argues that the impacts of key landscape features on river water quality at both the buffer zone and catchment scale should be considered and the thresholds that lead to abrupt changes in water quality should be identified, with some degree of clarity to guide and inform landscape planners.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information file (Table S2).

References

Jones, E. R., Bierkens, M. F. P. & van Vliet, M. T. H. Current and future global water scarcity intensifies when accounting for surface water quality. Nat. Clim. Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02007-0 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. A triple increase in global river basins with water scarcity due to future pollution. Nat. Commun. 15, 880. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44947-3 (2024).

Paule-Mercado, M. C. et al. Climate and land use shape the water balance and water quality in selected European lakes. Sci. Rep. 14, 8049. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58401-3 (2024).

Downing, J. A., Polasky, S., Olmstead, S. M. & Newbold, S. C. Protecting local water quality has global benefits. Nat. Commun. 12, 2709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22836-3 (2021).

Cao, Y. C. et al. Effects of landscape conservation on the ecohydrological and water quality functions and services and their driving factors. Sci. Total Environ. 861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160695 (2023).

Wu, T. et al. Identification of watershed priority management areas based on landscape positions: an implementation using SWAT. J. Hydrol. 619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129281 (2023).

Uuemaa, E., Antrop, M., Roosaare, J., Marja, R. & Mander, Ü. Landscape metrics and indices: an overview of their use in landscape research. Living Reviews Landsc. Res. 3, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.12942/lrlr-2009-1 (2009).

Frazier, A. E. & Kedron, P. Landscape metrics: past progress and future directions. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40823-017-0026-0 (2017).

Turner, M. G., Gardner, R. H., Turner, M. G. & Gardner, R. H. Landscape metrics. Landscape ecology in theory and practice: Pattern and process, 97–142 (2015).

Cardille, J. A. & Turner, M. G. Understanding landscape metrics. Learning landscape ecology: A practical guide to concepts and techniques, 45–63 (2017).

Cheng, X., Song, J. & Yan, J. Influences of landscape pattern on water quality at multiple scales in an agricultural basin of Western China. Environ. Pollut. 319, 120986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120986 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Water quality assessment and the influence of landscape metrics at multiple scales in Poyang lake basin. Ecol. Ind. 141, 109096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109096 (2022).

Stets, E. G. et al. Landscape drivers of dynamic change in water quality of US rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 4336–4343. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b05344 (2020).

Xu, Q., Yan, T., Wang, C., Hua, L. & Zhai, L. Managing landscape patterns at the riparian zone and sub-basin scale is equally important for water quality protection. Water Res. 229, 119280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.119280 (2023).

Rhodes, A. L., Newton, R. M. & Pufall, A. Influences of land use on water quality of a diverse new England watershed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 3640–3645. https://doi.org/10.1021/es002052u (2001).

Li, S., Gu, S., Liu, W., Han, H. & Zhang, Q. Water quality in relation to land use and land cover in the upper Han River Basin, China. CATENA 75, 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2008.06.005 (2008).

Haith Douglas, A. Land use and water quality in new York rivers. J. Environ. Eng. Div. 102, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1061/JEEGAV.0000440 (1976).

Kändler, M. et al. Impact of land use on water quality in the upper Nisa catchment in the Czech Republic and in Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 586, 1316–1325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.221 (2017).

Ngoye, E. & Machiwa, J. F. The influence of land-use patterns in the ruvu river watershed on water quality in the river system. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 29, 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2004.09.002 (2004).

Charbonneau, R. & Kondolf, G. M. Land use change in California, USA: nonpoint source water quality impacts. Environ. Manage. 17, 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02394661 (1993).

Shi, P., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Li, P. & Xu, G. Influence of land use and land cover patterns on seasonal water quality at multi-spatial scales. CATENA 151, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2016.12.017 (2017).

Pei, W. et al. Effect of landscape pattern on river water quality under different regional delineation methods: A case study of Northwest section of the yellow river in China. J. Hydrology: Reg. Stud. 262226725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101536 (2023).

Qiu, M., Wei, X., Hou, Y., Spencer, S. A. & Hui, J. Forest cover, landscape patterns, and water quality: a meta-analysis. Landscape Ecol. 38, 877–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-023-01593-2 (2023).

Shi, X. et al. Effects of landscape changes on water quality: A global meta-analysis. Water Res. 260, 121946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121946 (2024).

Liu, Z. & Yang, H. The impacts of Spatiotemporal landscape changes on water quality in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15 (2018).

Wu, J. & Lu, J. Spatial scale effects of landscape metrics on stream water quality and their seasonal changes. Water Res. 191, 116811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2021.116811 (2021).

Xu, S., Li, S. L., Zhong, J. & Li, C. Spatial scale effects of the variable relationships between landscape pattern and water quality: example from an agricultural karst river basin, Southwestern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 300, 106999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106999 (2020).

de Mello, K. et al. Multiscale land use impacts on water quality: assessment, planning, and future perspectives in Brazil. J. Environ. Manage. 270, 110879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110879 (2020).

Zhang, J., Li, S. & Jiang, C. Effects of land use on water quality in a river basin (Daning) of the three Gorges reservoir area, China: watershed versus riparian zone. Ecol. Ind. 113, 106226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106226 (2020).

Aalipour, M., Antczak, E., Dostál, T. & Amiri, B. J. Influences of Landscape Configuration on River Water Quality. Forests 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13020222 (2022).

Ding, J. et al. Influences of the land use pattern on water quality in low-order streams of the Dongjiang river basin, China: A multi-scale analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 551–552, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.162 (2016).

Zhang, J., Li, S., Dong, R., Jiang, C. & Ni, M. Influences of land use metrics at multi-spatial scales on seasonal water quality: A case study of river systems in the three Gorges reservoir area, China. J. Clean. Prod. 206, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.179 (2019).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 13, 3907–3925. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-3907-2021 (2021).

Mooney, R. J. et al. Outsized nutrient contributions from small tributaries to a great lake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 28175–28182. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001376117 (2020).

Qian, S. S., King, R. S. & Richardson, C. J. Two statistical methods for the detection of environmental thresholds. Ecol. Model. 166, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(03)00097-8 (2003).

Namugize, J. N., Jewitt, G. & Graham, M. Effects of land use and land cover changes on water quality in the uMngeni river catchment, South Africa. Phys. Chem. Earth. 105, 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2018.03.013 (2018).

Camara, M., Jamil, N. R. & Bin Abdullah, A. F. Impact of land uses on water quality in Malaysia: a review. Ecol. PROCESSES 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-019-0164-x (2019).

Shah, N. W. et al. The effects of forest management on water quality. For. Ecol. Manag. 522, 120397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120397 (2022).

Neary, D. G., Ice, G. G. & Jackson, C. R. Linkages between forest soils and water quality and quantity. For. Ecol. Manag. 258, 2269–2281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.05.027 (2009).

Nieder, R., Benbi, D. K. & Scherer, H. W. Fixation and defixation of ammonium in soils: a review. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 47, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-010-0506-4 (2011).

Udawatta, R. P., Garrett, H. E. & Kallenbach, R. L. Agroforestry and grass buffer effects on water quality in grazed pastures. Agroforest Syst. 79, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-010-9288-9 (2010).

Li, J. et al. Grassland restoration reduces water yield in the headstream region of Yangtze river. Sci. Rep. 7, 2162. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02413-9 (2017).

Jerch, R. L. & Phaneuf, D. J. Cities and water quality. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 107, 103998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2024.103998 (2024).

Oberascher, M., Rauch, W. & Sitzenfrei, R. Towards a smart water City: A comprehensive review of applications, data requirements, and communication technologies for integrated management. Sustainable Cities Soc. 76, 103442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103442 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable contributions.

Funding

This study was funded by Scientific Research Program for High-level Talents of Gannan Medical University (QD202422) awarded to XXW; The Talent Development Program for Young Scientific and Technological Professionals in the Early Career Stage in Jiangxi Province (20244BCE52226) awarded to XXW; Science and Technology Research Program (Youth Program) of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education awarded to XXW and Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Project of Hunan Province (CX20220720 and CX20220701).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BL and XXW: conceptualization; BL, XLH, QZ: data curation; BL and XXW: methodology; XXW: project administration; BL, XLH, QZ: result interpretation; XXW: supervision; BL: analysis validation; BL, XLH, QZ: visualization and edition; BL: writing-original draft; BL, XXW: writing–review; XXW: funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Huang, X., Zhong, Q. et al. Response of river water quality to landscape features in a subtropical hilly region. Sci Rep 15, 13528 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98575-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98575-y