Abstract

The Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) and the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides) are resident to the inshore waters of India. Despite urgent conservation concerns facing both species, population assessments and long-term monitoring efforts face several challenges, particularly due to limitations in conducting conventional visual surveys. Our study explores the use of combined acoustic and visual surveys along a 376 km\(^2\) area off the Sindhudurg coast, India, to address these limitations. We begin by examining the two platforms for efficiency in species detection by comparing encounter rates across acoustic and visual methods. Acoustic (0.04 groups/km) and visual (0.03 groups/km) encounter rates for humpback dolphins do not show a stark difference. However, acoustic (0.12 groups/km) and visual (0.03 groups/km) encounter rates for finless porpoises vary greatly. Visual and acoustic group size estimates also vary for both species. We then use generalized additive mixed models (GAMM) to determine factors responsible for variation in detectability between the two platforms. Distance from shore and vessel traffic are variables affecting mixed detections of humpback dolphins. Acoustic detections for finless porpoises are most influenced by distance from shore and depth. Our findings highlight the importance of considering species-specific variations in acoustic and visual detectability when designing integrated surveys for multiple species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indian coastal waters form an important habitat for a variety of marine mammal species, including the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) and the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides). However, these coastlines are also marked by densely populated human settlements that depend on the ocean as a primary source of resources1,2. Consequently, cetaceans in this region are increasingly at risk of local population declines due to direct and indirect human-induced changes to their environment3. These threats are further heightened for non-migratory species with restricted habitat preferences and small fragmented populations4. While conservation measures are best derived from empirical assessment of animal populations, information on abundance, distribution, and population trends are currently lacking for most cetacean species from Indian waters. These data gaps are particularly concerning for the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin and the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise, two species commonly occurring off the West Coast of India. Both species face imminent threats due to proximity to anthropogenic activities. In addition to increasing vessel traffic, coastal infrastructure development, and chemical and noise pollution, a major cause of concern is interactions with fisheries, often leading to incidental mortalities5,6. Based on a range-wide decrease in population trends, Indian Ocean humpback dolphins are already recognized as ‘Endangered’ by the IUCN Red List7. An assessment of Indian Ocean humpback dolphin populations indicates that current range-wide mortality events could result in a 50% decline in numbers within \(\approx\) 75 years spanning both past and future generations7. Data on overall population trends for the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise are lacking throughout their distribution range. However, given the high degree of anthropogenic pressure in their habitat8,9, it is suggested the species faces considerable population decline, thus placing them under the ‘Vulnerable’ category of the IUCN Red List5. Stranding and mortality events for both species are frequently reported along the Indian coast6,10. Finless porpoises are one of the most recorded species in mortality events, particularly across the west coast of India10. Within the past decade (2013–2023), the west coast of India alone has reported 159 mortalities of humpback dolphins and 139 for finless porpoises (Marine Mammal Research and Conservation Network of India [MMRCNI], http://www.marinemammals.in, accessed on 24 January 2024). These stranding data only represent documented events, and many mortalities potentially go unreported. Despite the availability of limited stranding and mortality records, the long-term consequences of these numbers cannot be quantified due to a lack of systematic population assessment of both species.

Abundance estimation efforts for humpback dolphins using photographic mark-recapture were initiated along the coast of Goa and Gujarat in 200211 and in Maharashtra between 2014 and 20166. However, population estimates from these surveys are unavailable due to low resighting rates and the absence of continuous surveys11. Systematic monitoring for finless porpoises has only been conducted along the Maharashtra coast (2014–2016)9. These surveys were primarily designed to study humpback dolphin populations and did not cover the habitat range of finless porpoises. As a result, robust abundance data are unavailable to derive a population assessment. Recommendations of the IWC subcommittee for small cetaceans12 and the IUCN species assessment reports7 all point towards an urgent need to gather population-level data for both species across Indian waters to address rising conservation concerns.

In Indian waters, most population estimation studies have been restricted to conventional methods such as visual line transects or photographic mark-recapture surveys11,13. However, these methods prove challenging for coastal cetaceans inhabiting shallow turbid waters, particularly for finless porpoises, due to their elusive behavior, small group sizes, and irregular surfacing patterns14. Besides habitat and species-based limitations, visual surveys also require adequately trained observers15. Cetacean research in India is still in the early stages, and ensuring continuous availability of trained marine mammal observers for long-term monitoring efforts is a challenge. Shortcomings in visual surveys can be addressed by integrating passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) tools into the survey protocol, offering solutions for species detection independent of environmental conditions and human observer bias16. Line transects surveys using hydrophone arrays towed behind vessels have successfully been implemented for beaked whales17, baleen whales18, sperm whales19,20 and smaller odontocete species21,22. Most studies that utilized a combined visual and acoustic survey protocol report a higher number of acoustic encounters than visual-only methods23. With the advancement in autonomous recording technology and improved hardware, towed array designs are now compact and relatively low-cost24. Towed arrays with autonomous recording capabilities eliminate the need for expensive data acquisition systems onboard research vessels25. These compact arrays can be easily deployed off smaller boats, making them more accessible to researchers working in areas where monitoring efforts face multiple logistical and financial constraints.

However, effectively identifying animal presence using an acoustic platform depends on the vocal behavior of the target species and the detectability of the acoustic signal in its environment. For species and habitats where the use of acoustic line transects is new, there is first a need to assess the efficacy of the platform using simultaneous visual and acoustic surveys to estimate detections missed by either platform26.

In our study area off the Sindhudurg coast, resident populations of humpback dolphins and finless porpoises co-occur, though both species are starkly different in morphology and behavior, creating variation in the two species’ visibility. Humpback dolphins are bigger, more surface active, and form big groups, whereas finless porpoises are extremely elusive and have irregular surfacing patterns with smaller group sizes27. Finless porpoises also lack a dorsal fin, which is usually a prominent visual cue when conducting cetacean surveys. The two species also exhibit distinct acoustic behavior27. Finless porpoises only produce narrow-band high-frequency echolocation clicks \(\ge\) 90 kHz28. These clicks are highly directional and attenuate significantly at distances greater than 500 m in shallow turbid environments29. Humpback dolphins, on the other hand, produce broadband echolocation clicks in frequencies ranging between 15 kHz to \(\ge\) 160 kHz, along with whistles and burst pulses30. The broadband nature of these sounds allows for humpback dolphins to be detected across greater distances31. Although surveys to monitor both species together are preferred due to logistical and financial limitations, these species-level variations in detectability can hamper field data collection. Increased effort to visually detect cryptic species may compromise the accuracy of data collection for other species. Our study aimed to evaluate the performance of combined acoustic and visual line transect surveys to assess whether an integrated approach may improve overall data collection for both target species. We compared differences in the species encounter rates across the two detection platforms as a metric to assess their utility in further monitoring studies. As species detectability is also closely associated with environmental conditions8, we used environmental variables corresponding to the species encounters to measure their influence on the detections across the two platforms. We use our results to help streamline methods for broadscale population-level data collections for these two coastal species that share a habitat but vary significantly in behavior and ecology. Additionally, our findings can inform best practices for allocating human effort and logistics toward vessel-based monitoring for the focal species across data-poor regions with limited resources.

Results

Acoustic and visual encounter rates were collected during 38 transects conducted between 2020 and 2023, which covered a total distance of 1233.2 km (Table 1) and recorded 114.1 h of acoustic data. Throughout the surveys, the acoustic and visual platforms operated simultaneously, ensuring the total duration of the sighting effort was always consistent with acoustic data collection. We logged a total of 216 (both acoustic and visual) encounters for the two species.

Indian Ocean humpback dolphin

A total of 63 on-effort humpback dolphin encounters were recorded throughout the study (Fig. 1). Of these, the mixed encounters accounted for 63.4% (n = 40), visual-only encounters corresponded to 14.2% (n = 9), and acoustic-only encounters accounted for 22.2% (n = 14). The overall encounter rate for humpback dolphins was 0.05 groups/km. The visual encounter rate for humpback dolphins was 0.03 groups/km, and the acoustic encounter rate was 0.04 groups/km. The difference between acoustic and visual encounter rates was not significant (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: W = 639.5, p-value = 0.3). Visual estimates of group sizes for humpback dolphins were between 1 and 25, with a mean group size of 5.4 (standard deviation, SD: ±5.2), and the acoustic estimates were between 1 and 16, with a mean group size of 3.2 (SD: ±2.7) (Fig. 2). While 65% (n = 26) of the visual group size estimates were higher than acoustic, 22.5% (n = 9) were the same, and 12.5% (n = 5) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: W = 577.5, p-value < 0.01).

Distance from shore (km), vessel traffic, and the tensor product of swell and sea state were the variables explaining the most variation in humpback dolphin encounters across detection types (Table 2). These variables had a significant effect on either visual or mixed detection types, but none of the variables showed any significance for acoustic detections. Distance from shore had a significant effect on mixed detections (p-value < 0.01), which were recorded within a range of 0.4 to 4.9 km from the shore. The highest rate of mixed detections occurred between 1.5 to 2 km from the shore. Acoustic detections were recorded between distances of 0.5 to 3.0 km from the shore, and visual detections were concentrated between 0.5 to 3.5 km. We observed an increase in mixed detections as distance from shore increased, whereas both acoustic and visual detections were seen to consistently decrease, especially beyond a distance of 1.5 km from the coastline (Fig. 3). Vessel traffic showed a borderline effect (p-value = 0.05) only on mixed detections, which were seen to gradually increase with an increase in the number of boats present during the encounters. We did not observe any significant effect of vessel traffic on acoustic and visual detections (Fig. 4). The tensor product of swell and sea state produced a non-significant result for the acoustic and mixed detection types, although the result for visual detections was borderline (p-value = 0.07). However, any suggested relationship could not be concluded from the tensor plots (Supplement).

Smooth for distance from shore (km) predicted by the GAMM for encounter rates of Indian Ocean humpback dolphins across detection type. Shaded portions indicate the 95% confidence intervals, color-coded according to the detection types. Vertical ticks on the X-axis indicate the distribution of encounters.

Smooth for the effect of vessel traffic predicted by the GAMM for encounter rates of Indian Ocean humpback dolphins across detection type. Shaded portions indicate the 95% confidence intervals, color-coded according to the detection types. Vertical ticks on the X-axis indicate the distribution of encounters.

Indo-Pacific finless porpoise

We recorded 153 encounters of finless porpoises (Fig. 5). Out of the total encounters, the acoustic-only encounters accounted for 74.5% (n = 114), and mixed encounters made up for 22.8% (n = 35). Of the total encounters, 2.6% (n = 4) were visual-only. The overall encounter rate for finless porpoises was 0.12 groups/km. The visual encounter rate was 0.03 groups/km, and the acoustic encounter rate was 0.12 groups/km. A comparison of the acoustic and visual encounter rates showed a significant difference between encounter rates estimated from the two detection types (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: W = 230.5, p-value < 0.0001).

Visual group estimates of finless porpoises were between 1 to 5 individuals with a mean group size of 2.0 (SD: ±1.1), whereas the acoustic group sizes ranged from 1 to 9 individuals with a mean group size of 3.3 (SD: ±1.9) (Fig. 6). 62% (n = 22) of the acoustic group estimates were higher than those estimated visually, and 17% (n = 6) were the same, whereas 20% (n = 7) were lower than visual estimates. A significant difference was observed between the acoustic and visual group size estimates (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: W = 869, p-value < 0.01).

Distance from shore (km), water depth (m), and the tensor product of swell and sea state were the most important variables for explaining finless porpoise encounters by detection type (Table 3). Distance from shore had a significant effect only on the acoustic detections (p-value < 0.05). Most acoustic detections were recorded between a distance of 0.3 to 5.3 km from shore, with the highest concentration of acoustic detections between 1 to 2 km. Mixed/visual detections were recorded at distances of 0.4 to 3.9 km from the shore, with most detections concentrated between 1.4 to 1.9 km. While we observed a slight increase in the mixed/visual detections up to 2 km from the coastline followed by a gradual decrease towards the 5 km boundary, distance from shore did not have a significant effect on this detection type (Fig. 7). Similar to distance from shore, depth (p-value < 0.01) had a significant effect only for acoustic detections. The water depth associated with the highest concentration of acoustic detections ranged between 9 and 11 m. The model showed an increase in acoustic detections across water depth, and acoustic detections remained constant in waters deeper than 15 m. The highest concentration of the mixed/visual detections was also similar to acoustic detections, mainly occurring between 9 to 11 m. However, we note a gradual decrease in the mixed/visual detections around 11 m, with very few records beyond 13 m (Fig. 8). The tensor product of swell and sea state had a borderline effect only on the mixed/visual detections (p = 0.06) (Table 3) and had no effect on the acoustic detections (Supplement).

Smooth for distance from shore (km) predicted by the GAMM for encounter rates of Indo-Pacific finless porpoises across detection type. Shaded portions indicate the 95% confidence intervals, color-coded according to the detection types. Vertical ticks on the X-axis indicate the distribution of encounters.

Discussion

We present a comparison of acoustic and visual encounter rates for humpback dolphins and finless porpoises from the Sindhudurg region of India. While acoustic and visual methods showed complementary results for humpback dolphin detections, passive acoustic monitoring was most effective in detecting finless porpoises.

A key concern in comparing and matching encounter rates between acoustic and visual surveys is the difference between the detection ranges of the two platforms32. If the detection range of the acoustic platform is significantly greater than the visual, it may record more encounters simply from an ability to detect signals across wider distances. This could potentially inflate encounter rates from one platform or make it difficult to match detections across the two if such differences in detection range were not considered. Acoustic signals of some cetacean species are likely to be detected across greater ranges than visual cues32,33. However, for most smaller species of odontocetes, the visual and acoustic detection ranges are fairly comparable34. Visual detections of humpback dolphins can occur at greater distances, given their large body size and the presence of a fin. Similarly, the acoustic detection range for humpback dolphins could extend further than 1 km from the survey track, influenced by the broadband nature of their echolocation clicks. However, given the shallow bathymetry and high sediment content of the habitat, echolocation clicks are unlikely to be detected clearly beyond 1 km31. While tonal sounds of humpback dolphins (whistles and burst pulses) would propagate further, these were not considered in the analysis since we used click trains as the only detection unit to define acoustic encounters. A preliminary examination of localized distances from humpback dolphin click trains confirmed that most detections were within the same range as visual detections. Given these conditions, the likelihood of including acoustic encounters recorded beyond the visual detection range was rare. Examination of localized acoustic distances for finless porpoises showed accurate detections up to a maximum distance of 300–350 m from the towed array. Our findings are similar to observations made for acoustic detection distances for finless porpoises in China29. Given the narrow-band high-frequency properties of their echolocation clicks, sound propagation in a shallow turbid environment is often compromised. Visual detection distances for finless porpoises also fall within a similar range, as sighting the species further away from the survey track is difficult. Hence, acoustic and visual detection ranges were not starkly different for finless porpoises. Thus, for both species, we assume a good overlap between the acoustic and visual detection ranges within our study area.

Most humpback dolphin encounters were simultaneously recorded on both platforms, with neither method demonstrating significantly superior performance. Visual group sizes for humpback dolphins were generally higher than acoustic group estimates. This trend was consistent with a study from Malaysia comparing visual and acoustic group estimates for Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins27. A similar variation between acoustic and visual group size estimates has been observed in Irrawaddy dolphins35, suggesting larger groups may vocalize at lower rates. Preliminary analysis of acoustic data from our study area showed a similar trend with fewer individual echolocation tracks observed in the presence of larger groups compared to smaller group sizes. The encounter rate model for humpback dolphins explains factors responsible for variations across mixed detection types. Mixed detections were most influenced by distance from shore and the presence of vessels. Across their distribution range, humpback dolphin populations exhibit a habitat preference for coastal waters, primarily occurring within 2–3 km from the shoreline36,37. During our surveys, most humpback dolphin groups recorded beyond a distance of 2–3 km from the coast were either lone individuals or smaller groups traveling. A higher number of click trains and increased vocalization rate within smaller groups could be why most of these encounters were detected simultaneously on both platforms38. Mixed detections were also correlated with the presence of vessel traffic, indicating a potential association with the presence of preferred prey distribution and foraging behavior. The study area has high fishing intensity throughout the year, and vessel traffic primarily comprises active fishing boats (purse seiners, trawlers, and gill nets). While we do not discuss predominant group behavior in this study, foraging and feeding humpback dolphin groups have previously been recorded around fishing vessels in the study area6. Mixed events suggest the presence of actively foraging individuals using both acoustic cues for coordination and surface-active behavior, making animals detectable on both platforms39,40. The combined effect of swell and sea state had a borderline effect only on visual detections. However, a conclusive relationship could not be drawn from the GAMM model. A primary reason for this could be that most surveys were conducted in Beaufort sea states ranging between 0–3 and rarely exceeding 4. The data, therefore, may not present enough variation to draw an inference. The humpback dolphin model explained low variation in the data (17.4% deviance explained); however, this may be due to the relatively small sample size (n = 63) of encounters. Due to their extremely coastal distribution, a zig-zag survey designed closer to the shoreline, with more effort concentrated up to 2–3 km from the shore, would be preferable for monitoring this species. Overall, our findings indicate that combining visual and acoustic surveys is most effective for studying humpback dolphin populations. These findings are consistent with survey method recommendations derived for monitoring humpback dolphins in Malaysia27.

Acoustic encounter rates for finless porpoises were significantly higher compared to the visual encounter rates. These results align with studies for finless porpoises across China and Malaysia that report higher numbers of acoustic detections compared to visual27,29. We also observed variation in the group sizes estimated via acoustic and visual methods for finless porpoise encounters. However, unlike the study from Malaysia, which recorded larger group sizes (mean: 6.5 SD: ± 8.5) using visual detections as compared to acoustic (mean: 1.8 SD: ± 1.6)27, our estimates suggest the opposite. Potential factors for higher acoustic group size estimates can be attributed to the highly directional nature of the acoustic signal and reduced visibility due to turbidity in the study area. Both factors can cause individuals to echolocate constantly, contributing towards the detection and identification of distinct individual echolocation tracks. The finless porpoise encounter rate model suggests certain factors contributing to a higher frequency of acoustic detections. Acoustic detections were mainly influenced by distance from shore and depth. A higher frequency of acoustic detections recorded further from the coastline can be linked to an increased presence of porpoises in these areas. These sites could be associated with potential foraging areas. Studies show foraging porpoises spend an extensive amount of time echolocating41, which could explain the increase in acoustic detections in these locations. However, the variable was not found to have a significant effect on the mixed/visual detection types. A potential reason for this could be that the relatively small sample size of the mixed/visual detections (n = 39) compared to the acoustic detections (n = 114) might not provide enough variation in the data to observe a noticeable pattern. We also note that distance from shore was retained in the final models of both species, and the variable is probably a stronger indicator for overall habitat preference42,43 than the efficiency of the monitoring platform. Finless porpoise detections varied significantly across the depth profile, with a higher number of acoustic detections recorded beyond depths of 11 m than mixed/visual. These differences can be associated with longer dive times in depths beyond 2.5 m, as observed during studies on tagged individuals35. Studies have found finless porpoises also tend to swim slower at the end of dives beyond 2.5 m, suggesting these dives are linked to foraging events35. Finless porpoises also tend to use echolocation uniformly across different depths. Previous studies have established that depth is not a limiting factor for acoustic detections of this species44. An absence of visual detections across the depth profile could indicate individuals or groups actively foraging and feeding, characterized by longer dives and underwater duration. We found that the acoustic platform outperformed the visual across the depth profile. Although the combined effect of sea state and swell affected mixed/visual detections, it only showed a borderline effect. Visual monitoring methods and visual detection rates for most cetacean species are greatly influenced by oceanic weather conditions like increasing sea states, unfavorable wind speeds, and high wave height8,45. Although finless porpoises in certain geographic areas are reported to be visually detectable in sea states up to Beaufort 246,47,48, we had difficulty in detecting individuals when sea state \(\ge\)2 were combined with swell. Similar complications have been noted during visual surveys for finless porpoises in the Yellow Sea off China49. Range-wide, finless porpoises are known to be cryptic, with irregular surfacing patterns and small group sizes47. These behavioral traits, along with their small size and lack of a dorsal fin, provide sparse cues for visual monitoring. Overall, our data had a low number of visual detections (n = 39) for finless porpoises, and the model explained only 14.5% deviance in the data. This suggests some other factors not included in the model influence the visual and acoustic detectability of the species. Due to the elusive nature of finless porpoises, the absence of visual detections may be associated with behavioral ecology rather than external environmental conditions alone. Acoustic monitoring proved favorable, as the species vocalize constantly, irrespective of group sizes and behavioral states. Given the significantly high number of acoustic detections, we conclude that PAM is a more efficient tool for monitoring finless porpoises in the study area.

While our study provides insights into variations in acoustic and visual encounter rates of the two species, some limitations of the dataset should be noted. One constraint was the small sample size of visual-only encounters of finless porpoises (n = 4). As a result, we merged the visual-only and mixed detection types. This decision could potentially have some effect on the ability of the GAMM to detect variations within the data. Another limitation we recognize is that the sampling duration is restricted to the same hours throughout the study period. It is possible that animals may display variations in surface and acoustic behavior at different times of the day31,50. Future studies can address this by conducting surveys at different times of the day to account for potential diel variations in species behavior.

Implications for species monitoring

The Sindhudurg coast is part of a 4327 km\(^2\) region in the Arabian Sea that was demarcated as an Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) by the IUCN Marine Mammal Protected Area Task Force51,52 in 2019. The area primarily qualified for an IMMA based on the presence of resident populations of humpback dolphins and finless porpoises, which are vulnerable to anthropogenic pressures. The IMMA Task Force has highlighted the importance of continuously monitoring designated areas and vulnerable animal populations to detect any changes in distribution patterns and identify decreasing population trends51. The methods described in this study offer a robust framework that can be integrated within monitoring protocols to generate long-term population trends and provide rapid species assessment in response to increasing anthropogenic pressures. These encounter rates can be further analyzed to provide estimates of population densities and abundances, which can strengthen IUCN Red-List assessment reports for both species from Indian waters5,53.

Given the limited resources and trained observers available for studying cetaceans in developing countries like India, our approach of integrating acoustic and visual surveys provides a more feasible method to monitor co-occurring species together. We suggest such joint survey methods should account for varying detectability (acoustic and visual) of the target species to make monitoring efforts most efficient.

Population estimation surveys for humpback dolphins would best benefit from a combination of acoustic and visual monitoring. While we found the two detection platforms complement each other, it is important to highlight that PAM alone cannot provide adequate information on group sizes. Group size estimates can be essential when converting encounter rates to abundance and density estimates54. A combined acoustic and visual method would offer more reliable abundance estimates as we find visual data provides better information on group size estimates for this species. However, if the sole aim of a monitoring survey is to detect the presence of humpback dolphins, both standalone PAM or visual surveys would provide equally robust data. In the absence of trained observers, acoustic surveys offer another advantage of having data processed in a lab and thus require minimal personnel onboard for vessel-based surveys. In contrast, for finless porpoise surveys, acoustic detections were three-fold higher than visual detections. This difference was irrespective of weather conditions. Considering the elusive behavior of the species, even favorable sea states did not yield a high success rate for the visual platform in detecting the species. For finless porpoises, we recommend conducting acoustic surveys, even if trained observers are not available for simultaneous visual surveys. Acoustic data reliably provided robust encounter rates for the species, with minimal need for simultaneous visual validation. If localization distances are added, these standalone acoustic detections can also be converted into density and abundance estimates18. Overall, acoustic surveys also provide greater flexibility when conducting surveys in terms of weather conditions or daylight.

While this study does not focus on informing abundance or density estimates, our results highlight species-specific pros and cons of the two observation platforms, which should help to inform long-term monitoring efforts. These co-occurring species have significantly different ecology and acoustic behavior, and combined monitoring efforts would benefit from considering these differences when designing population estimation surveys.

Methods

Survey area

Surveys were conducted in Indian waters along the Sindhudurg coastline from Vijaydurg (16°33′24.72″N, 73°19′5.47″E) to Redi (15°44′43.95″N, 73°39′7.29″E) (Fig. 9). The survey area has a primarily sandy seafloor interspersed with rocky outcrops. The coastline is extremely shallow, with a gentle slope gradient, and the overall water depth within the survey region ranges from 2 m to 25 m. The study area extended \(\approx\)6km from the shoreline, forming a polygon of 376 km\(^2\). The polygon was stratified into seven blocks and labeled numerically from north to south (1–7) (Fig. 9). Following initial trials, blocks 4 and 7 were excluded from the survey effort due to their extremely shallow and rocky bathymetry, which made maneuvering the research vessel with the towed acoustic array difficult.

Field data collection

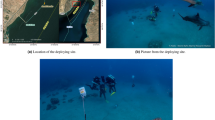

Combined acoustic and visual transects following a distance sampling protocol were conducted between 2020–2023 (Table 1). The zigzag line transects were designed in Distance 7.255 and were laid across the gradient of distribution of the focal species. An 11-meter modified trawler was used as a survey vessel throughout the study period. The vessel was equipped with a viewing platform approximately 2.5 m above the water surface. Transect speed was maintained between 11 and 12 km/h throughout the data collection period. Transects were on-effort only during daylight hours between 06:00 to 14:00 IST and in sea state \(\le\)4 Beaufort. Transects were conducted in passing mode, where the vessel continued to move along the survey track and did not approach or stop when the observers sighted a focal group56. The vessel was temporarily navigated off-track only in events where active trawling boats were directly in line with the transect.

A team of three trained observers was positioned on the platform (located at port, center, and starboard, respectively) to scan the water surface continuously. The observers covered a 140\(^\circ\) view between the starboard and port observers, and the center covered 40\(^\circ\) (20\(^\circ\) on either side) of the bow. An angle board was placed at the vessel’s bow, with the bow marking 0\(^\circ\). Observers continuously recorded environmental conditions, visibility (glare), sea state (in Beaufort), and swell height (in meters), along with presence, activity, and type of vessel traffic within a 1 km radius of the transect. Although we recorded glare at the beginning of each transect, it was not found to affect detectability as all observers wore appropriate polarized sunglasses. At every visual encounter of the focal species, observers recorded a sighting angle and radial distance to the focal group. Radial distances were estimated by eye, and all observers were trained in distance estimation throughout the survey effort. A GPS location was marked for each visual encounter on a handheld GPS device (Garmin 12H), and observers noted a minimum, maximum, and best group size estimate for the sighting57. Data on group compositions and predominant group behavior were collected opportunistically.

Acoustic data collection

A custom-made linear four-channel acoustic array was towed behind the vessel continuously to record the focal species independently of visual observations. The array was customized based on a design developed by Barkley et al. (2016)24 with modifications to the housing. The recording setup was contained in a rigid 6.35 mm PVC tube enclosing a thinner 1.5 mm PVC tube with four slots for hydrophones. The array had slots towards the opening and closing caps for flooding with seawater. Two pairs of HTI 96-Min hydrophone elements (HighTech Inc, Long Beach, MS, USA) were suspended in the inner tube using O-rings, taking care to ensure the cable did not touch the wall of the housing tube. The distance between each element within a pair was 25 cm, and the pairs were spaced 50 cm apart. All hydrophones had a flat frequency response of 2 Hz - 30 kHz, with a preamp sensitivity of \(-164\,\text {dB re:} 1\,\text {V/}\mu \text {Pa}\). The hydrophones were equipped with a 1 kHz high-pass filter to partially reduce flow and vessel noise in recordings. The hydrophones had a sensitivity range between \(-165\,\text {dB re:} 1\,\text {V/}\mu \text {Pa}\) to \(-162\,\text {dB re:} 1\,\text {V/}\mu \text {Pa}\). The hydrophones were connected to a four-channel autonomous recorder type SoundTrap ST4300 (Ocean Instruments, Auckland, NZ). The ST4300 had a frequency bandwidth of 20 Hz to 90 kHz ±3dB and an internal gain setting of 4dB. All four channels were sampled simultaneously and continuously at 288 kHz sampling rate and 16-bit resolution. File size was limited to 5 min per file for ease of downloading the data. The array was equipped with a downrigger type 2152 High-Speed Planer (Pro-Troll, Concord, CA, USA) at \(\approx\)4 m behind the vessel, suspended via a 1.5 meter slack line to maintain a steady horizontal position in the water column and to obtain a consistent towing depth between 4 and 5 m. Array depth was controlled by the tow line in certain shallow sections of the survey area and monitored with a depth sensor type Sensus UltraPro (ReefNet, Mississauga, ON, Canada). The array was towed between 23 and 25 m behind the survey vessel. All ST4300 data files were downloaded in the raw SUD format for further analysis. SUD files were decompressed to generate a set of WAV files for each survey.

Acoustic encounters

Acoustic data were manually screened in Raven Pro 1.6 (K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics, Cornell University, USA) to detect the presence of the focal species. Humpback dolphins and finless porpoises produce distinct acoustic cues which can be differentiated easily. For both species, the first and last detected acoustic cues were marked in each file. Echolocation clicks, together with tonal sounds, were used to detect the presence of humpback dolphins. An acoustic encounter for finless porpoises was defined by a silence period of 5 min between successive detections. A 5-min window was chosen considering an average swimming speed of 4.5 km/h for finless porpoises29. Since the survey vessel maintained a constant speed of 11–12 km/h, it was fast enough to avoid duplicate counts. Considering the acoustic detection range of finless porpoise clicks29, in addition to their tendency to echolocate constantly26, a silence period of 5 min was a good indicator for a new acoustic encounter. Encounters for humpback dolphins were separated by a silence period of 15 min between acoustic detections, given a longer detection range for their broadband signals31. The survey vessel speed was also fast enough to avoid duplicate encounters with humpback dolphins, considering their swimming speed between 2.5–6 km/h58,59.

Acoustic group sizes

Data for both species were further processed in PAMGuard (version 1.15.17)60 using the click detector and click classifier module. Echolocation click trains of both species were manually marked as events. Each event corresponded to a series of clicks, with changing bearing angles as the vessel crossed the vocalizing animals. Individual echolocation tracks within the predefined time bins matching visual encounters were counted to estimate the best group size from the acoustic data.

Visual encounters

Visual encounters were defined as a sighting of one or more individuals of the same species in an area. To keep data consistent and comparable between the acoustic and visual methods, the same time bins of 5 min and 15 min were used to segregate successive events. For visual encounters, as with acoustic encounters, no attempts were made to identify individuals and encounters beyond the defined time bins were treated as independent events61. Since the recording system was autonomous and all acoustic data were post-processed, the acoustic and visual encounters did not influence each other. After data processing, each encounter was labeled with a corresponding detection type (acoustic, visual, or mixed). Encounters were labeled “mixed” when simultaneous acoustic and visual detection occurred in the same timeframe. Time taken to travel between zigzag lines was taken as off-effort, and visual encounters during this time were marked accordingly. Acoustic encounters for off-effort sections were identified using timestamps from the WAV files. All off-effort data were excluded from the analysis. Transects were segmented into halves, and midpoints for each segment were marked in QGIS using the QChainage plugin version 3.10.10. Segmented transects with the half nearest to shore were labeled “in,” and the half extending to the boundary of the survey polygon was labeled “out.” Depth (in meters) and distance from shore (in kilometers) for each encounter and segment midpoints were calculated post-hoc using the GEBCO bathymetry chart http://www.gebco.net and NNJoin plugin version 3.1.3 in QGIS 3.24.2 respectively.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in R (ver 4.3.1, R Core Team 2021)62. The overall acoustic encounter rate for both species was derived by combining acoustic-only detections with mixed detections. Similarly for the visual encounter rate, visual-only and mixed detection types were both considered. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the acoustic and visual encounter rates and estimated group sizes using acoustic and visual methods. Visual and acoustic group estimates were only compared for mixed detection types.

Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) were used to assess the relationship between encounters as a function of detection category and predictor variables. GAMMs were chosen as they are flexible and do not assume a linear relationship between the response and predictor variables63. GAMMs are also suitable for non-normally distributed data, which are common in ecological studies. GAMMs were fitted to the data using the mgcv package64 by including a random effect within the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) framework. Separate GAMMs were fitted for both species, with the number of encounters per segment across each detection category as the response variable. Detection type (acoustic, visual, or mixed) was included as a factor. Smooth terms for the explanatory variables were estimated separately for each detection type using the “by = factor” argument (Supplement). Segments without encounters were also included and were given a count of zero. Predictor variables included swell (m), sea state (Beaufort), depth (m), distance from shore (km), and vessel traffic (number of boats) within 1 km of the transect. To keep data consistent between segments corresponding to the presence and absence of encounters, measures for depth and distance from shore were taken using the midpoint of each segment. To test the combined effect of swell (m) and sea state, we included these as a full tensor product interaction since the two variables operated at different scales. The transect segment length (effort) was log-transformed and included as an offset. The number of knots for each smooth term was manually restricted between three and five to avoid overfitting the data. Variables with a value of p < 0.05 were considered to have a significant effect, and variables with p < 0.1 were considered borderline.

As the data structure included encounters per segment across each detection type, a unique transect label (including month, year, transect ID, and segment) was included as a random effect. Multicollinearity between predictor variables was tested by computing variance inflation factor (VIF) scores using the car package65, with a cutoff of VIF \(\ge\) 366. The model was checked for autocorrelation following the method outlined by Zuur et al. 2010 using the acf function in the itsadug package67.

The visual and mixed detection types for finless porpoise encounters were combined into a single category (type = mixed/visual) as the number of only visual detections was extremely small (n=4). Group size was not included as a variable in the GAMMs as the model could not be fitted accurately with missing values across detection types.

Different distribution families, including Poisson, negative binomial, quasi-Poisson, and Tweedie, were tested. The Tweedie family is flexible to accommodate zero-inflated and overdispersed data and was considered the most appropriate fit for both models based on diagnostic plots (Supplement). Tweedie GAMMs were built using the tw function in mgcv, which allows the function to estimate p automatically during fitting, where p assesses the relation between the mean and the variance of the distribution. The value of p ranges between 1 and 2, where p = 1 indicates a Poisson distribution and p = 2 indicates a gamma distribution. We used the restricted maximum likelihood (REML function) as the optimization method. Model diagnostics were performed using the mgcViz package68. The dredge function in the MuMIN package69 was used to conduct backward model selection. The final model for each species was chosen based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values within a \(\Delta\)AIC score of \(<2\) units of the top model.

Data availability

All datasets from the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Martínez, M. L. et al. The coasts of our world: Ecological, economic and social importance. Ecol. Econ. 63, 254–272 (2007).

Sudha Rani, N., Satyanarayana, A. & Bhaskaran, P. K. Coastal vulnerability assessment studies over India: A review. Nat. Hazards 77, 405–428 (2015).

Nelms, S. E. et al. Marine mammal conservation: Over the horizon. Endanger. Species Res. 44, 291–325 (2021).

Wang, J., Yang, S. & Reeves, R. Report of the first workshop on conservation and research needs of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins. Sousa chinensis (2004).

Wang, J. & Reeves, R. Neophocaena phocaenoides. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2017). Accessed on 30 November 2023.

Jog, K. et al. Risks associated with the spatial overlap between humpback dolphins and fisheries in Sindhudurg, Maharashtra, India. Endanger. Species Res. 53, 35–47 (2024).

Braulik, G. T., Findlay, K., Cerchio, S. & Baldwin, R. Assessment of the conservation status of the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) using the IUCN red list criteria. Adv. Mar. Biol. 72, 119–141 (2015).

Minton, G., Peter, C. & Tuen, A. A. Distribution of small cetaceans in the nearshore waters of Sarawak, East Malaysia. Raffles Bull. Zool. 59 (2011).

Sule, M. et al. A review of finless porpoise records from India with a special focus on the population in Sindhudurg, Maharashtra. International Whaling Commission, Primary paper SC/67A/SM/09 (2017).

Dudhat, S. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis identifies marine mammal stranding hotspots along the Indian coastline. Sci. Rep. 12, 4128 (2022).

Sutaria, D. & Jefferson, T. A. Records of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis, Osbeck, 1765) along the coasts of India and Sri Lanka: An overview. Aquat. Mamm. 30, 125–136 (2004).

International Whaling Commission. Annex m. report of the sub-committee on small cetaceans. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 18, 313–314 (2017).

Sutaria, D. & Marsh, H. Abundance estimates of Irrawaddy dolphins in Chilika Lagoon, India, using photo-identification based mark-recapture methods. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 27 (2011).

Kuit, S. H., Ponnampalam, L. S., Hammond, P. S., Chong, V. C. & Then, A.Y.-H. Abundance estimates of three cetacean species in the coastal waters of Matang, Perak, Peninsular Malaysia. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 31, 3120–3132 (2021).

Hammond, P. S. et al. Estimating the abundance of marine mammal populations. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 735770 (2021).

Andriolo, A. et al. Marine mammal bioacoustics using towed array systems in the western south Atlantic Ocean. In Advances in Marine Vertebrate Research in Latin America: Technological Innovation and Conservation 113–147 (2018).

Barlow, J. et al. Trackline and point detection probabilities for acoustic surveys of Cuvier’s and Blainville’s beaked whales. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134, 2486–2496 (2013).

Norris, T. F., Dunleavy, K. J., Yack, T. M. & Ferguson, E. L. Estimation of Minke whale abundance from an acoustic line transect survey of the Mariana Islands. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 33, 574–592 (2017).

Barlow, J. & Taylor, B. L. Estimates of sperm whale abundance in the Northeastern Temperate Pacific from a combined acoustic and visual survey. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 21, 429–445 (2005).

Sigourney, D. B., DeAngelis, A., Cholewiak, D. & Palka, D. Combining passive acoustic data from a towed hydrophone array with visual line transect data to estimate abundance and availability bias of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). PeerJ 11, e15850 (2023).

Martin, M. J., Gridley, T., Roux, J.-P. & Elwen, S. H. First abundance estimates of Heaviside’s (Cephalorhynchus heavisidii) and dusky (Lagenorhynchus obscurus) dolphins off Namibia using a novel visual and acoustic line transect survey. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 555–659 (2020).

Ollier, C., Sinn, I., Boisseau, O., Ridoux, V. & Virgili, A. Matching visual and acoustic events to estimate detection probability for small cetaceans in the ACCOBAMS Survey Initiative. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1244474 (2023).

Oleson, E. M., Calambokidis, J., Barlow, J. & Hildebrand, J. A. Blue whale visual and acoustic encounter rates in the Southern California bight. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 23, 574–597 (2007).

Barkley, Y., Barlow, J., Rankin, S., D’Spain, G. L. & Oleson, E. M. Development and testing of two towed volumetric hydrophone array prototypes to improve localization accuracy during shipboard line-transect cetacean surveys. NOAA Technical Memorandum (2016).

Barlow, J. Design of a flooded housing for a towed autonomous hydrophone recording system. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS (2021).

Akamatsu, T., Wang, D., Wang, K. & Wei, Z. Comparison between visual and passive acoustic detection of finless porpoises in the Yangtze River, China. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109, 1723–1727 (2001).

Kimura, S. S., Sagara, T., Yoda, K. & Ponnampalam, L. S. Acoustic identification of the sympatric species Indo-Pacific finless porpoise and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin: An example from Langkawi, Malaysia. Bioacoustics 31, 545–561 (2022).

Li, S., Wang, K., Wang, D. & Akamatsu, T. Echolocation signals of the free-ranging Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientialis). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 3288–3296 (2005).

Akamatsu, T. et al. Estimation of the detection probability for Yangtze finless porpoises (Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis) with a passive acoustic method. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 4403–4411 (2008).

Yang, L. et al. Description and classification of echolocation clicks of Indian Ocean humpback (Sousa plumbea) and Indo-Pacific bottlenose (Tursiops aduncus) dolphins from Menai Bay, Zanzibar, East Africa. PLoS One 15, e0230319 (2020).

Wang, Z.-T. et al. Passive acoustic monitoring the diel, lunar, seasonal and tidal patterns in the biosonar activity of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in the Pearl River Estuary, China. PLoS One 10, e0141807 (2015).

Rayment, W., Webster, T., Brough, T., Jowett, T. & Dawson, S. Seen or heard? A comparison of visual and acoustic autonomous monitoring methods for investigating temporal variation in occurrence of southern right whales. Mar. Biol. 165, 1–10 (2018).

Dalpaz, L. et al. Better together: Analysis of integrated acoustic and visual methods when surveying a cetacean community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 678, 197–209 (2021).

Gridley, T. et al. Towed passive acoustic monitoring complements visual survey methods for Heaviside’s dolphins Cephalorhynchus heavisidii in the Namibian Islands marine protected area. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 42, 495–506 (2020).

Akamatsu, T. et al. Counting animals using vocalizations; A case study in dolphins. In 2013 IEEE International Underwater Technology Symposium (UT) 1–4 (IEEE, 2013).

Hemami, M.-R., Ahmadi, M., Sadegh-Saba, M. & Moosavi, S. M. H. Population estimate and distribution pattern of Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) in an industrialised bay, northwestern Persian Gulf. Ecol. Indic. 89, 631–638 (2018).

Stensland, E., Carlén, I., Särnblad, A., Bignert, A. & Berggren, P. Population size, distribution, and behavior of Indo-Pacific bottlenose (Tursiops aduncus) and humpback (Sousa chinensis) dolphins off the south coast of Zanzibar. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 22, 667–682 (2006).

Bono, S. B. A. Acoustic behavior of small cetaceans in northwest Peninsular Malaysia in relation to behavioral, environmental, and anthropogenic factors (Kyoto University, 2022).

Van Parijs, S. M. & Corkeron, P. J. Boat traffic affects the acoustic behaviour of pacific humpback dolphins, Sousa chinensis. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 81, 533–538 (2001).

Bono, S. et al. Whistle variation in Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) in relation to behavioural and environmental parameters in northwestern peninsular Malaysia. Acoust. Aust. 50, 315–329 (2022).

Akamatsu, T., Wang, D., Wang, K., Li, S. & Dong, S. Scanning sonar of rolling porpoises during prey capture dives. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 146–152 (2010).

Koper, R. P., Karczmarski, L., du Preez, D. & Plön, S. Sixteen years later: Occurrence, group size, and habitat use of humpback dolphins (Sousa plumbea) in Algoa Bay, South Africa. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 32, 490–507 (2016).

Fadzly, N. Habitat use and behaviour of the Irrawaddy dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris and the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise, Neophocaena phocaenoides off the West Coast of Penang Island, Malaysia. Raffles Bull. Zool. 71, 169–194 (2023).

Akamatsu, T., Wang, D. & Wang, K. Off-axis sonar beam pattern of free-ranging finless porpoises measured by a stereo pulse event data logger. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 3325–3330 (2005).

Harwood, L. A. & Joynt, A. Factors influencing the effectiveness of Marine Mammal Observers on seismic vessels, with examples from the Canadian Beaufort Sea (Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Science, 2009).

Shirakihara, M., Shirakihara, K. & Takemura, A. Distribution and seasonal density of the finless porpoise Neophocaena phocaenoides in the coastal waters of western Kyushu, Japan. Fish. Sci. 60, 41–46 (1994).

Jefferson, T. A. & Moore, J. E. Abundance and trends of Indo-Pacific finless porpoises (Neophocaena phocaenoides) in Hong Kong waters, 1996–2019. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 574381 (2020).

Fang, L. et al. Use of passive acoustic monitoring to document the distribution of the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise in the south-east region of Pearl River Estuary, China: Implications for conservation and management. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 32, 1428–1436 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Distribution and abundance of the east Asian finless porpoise in the coastal waters of Shandong Peninsula, Yellow Sea, China. Fishes 8, 410 (2023).

Wang, Z., Akamatsu, T., Wang, K. & Wang, D. The diel rhythms of biosonar behavior in the Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) in the port of the Yangtze river: The correlation between prey availability and boat traffic. PLoS One 9, e97907 (2014).

Task, I. M. M. P. A. Force. 2019. Important Marine Mammal (2019).

Force, I.-M. M. P. A. T. Sindhuburg-Karwar imma factsheet (2021). Downloaded on [01 June 2024].

Braulik, G., Natoli, A., Sutaria, D. & Vermeulen, E. Sousa plumbea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T82031633A230253271.en (2023).

Gerrodette, T., Perryman, W. L. & Oedekoven, C. S. Accuracy and precision of dolphin group size estimates. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 35, 22–39 (2019).

Thomas, L. et al. Distance software: Design and analysis of distance sampling surveys for estimating population size. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 5–14 (2010).

Schwarz, L. K. et al. Comparison of closing and passing mode from a line-transect survey of delphinids in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 11, 253–265 (2010).

Baird, I. G. & Beasley, I. L. Irrawaddy dolphin Orcaella brevirostris in the Cambodian Mekong River: An initial survey. Oryx 39, 301–310 (2005).

Piwetz, S., Hung, S., Wang, J., Lundquist, D. & Würsig, B. Influence of vessel traffic on movements of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis) off Lantau Island, Hong Kong. Aquat. Mamm. 38, 325 (2012).

Würsig, B., Parsons, E., Piwetz, S. & Porter, L. The behavioural ecology of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in Hong Kong. In Advances in Marine Biology, vol. 73, 65–90 (Elsevier, 2016).

Gillespie, D. et al. Pamguard: Semiautomated, open source software for real-time acoustic detection and localisation of cetaceans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 30, 54–62 (2008).

McCullough, J. L. et al. An acoustic survey of beaked whales and Kogia spp. in the Mariana Archipelago using drifting recorders. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 664292 (2021).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Zuur, A. F. et al. Things are not always linear; additive modelling. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R 35–69 (2009).

Wood, S. & Wood, M. S. Package ‘mgcv’. R package version 1, 729 (2015).

Fox, J. et al. The car package. R Found. Stat. Comput. 1109, 1431 (2007).

Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N. & Elphick, C. S. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 3–14 (2010).

van Rij, J., Wieling, M., Baayen, R. H., van Rijn, H. & van Rij, M. J. Package ‘itsadug’ (2017).

Fasiolo, M. et al. Package ‘mgcviz’. Visualisations for generalised additive models (2020).

Barton, K. & Barton, M. K. Package ‘mumin’. Version 1, 439 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank all our captains, crew, and research assistants involved in field data collection. We thank Tina Yack for help with the click detector and classifier modules in PAMGuard. We thank Mahi Mankeshwar for providing the bathymetry charts. We thank Raymond Mack for designing the array. Funding for the towed array was provided by The Marine Conservation Action Fund, New England Aquarium, USA. Funding for field data collection was provided by The Rufford Foundation, UK, The Wildlife Conservation Trust, Small Grants, India, The Marine Mammal Commission, USA and The Mangrove Foundation, India. We thank the Maharashtra State Forest Department and The Mangrove Foundation for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IB, HK, and DH conceptualized and designed the study. IB carried out the data collection under the supervision of DH, HK, and VVR. IB and DH analyzed the data. IB prepared the manuscript. All authors edited, reviewed, and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

The surveys conducted were non-invasive and did not include approaching the focal animals in any way. All surveys were approved by the Maharashtra State Forest Department, which oversees research on wild animals. Surveys strictly adhered to the rules set by the forest department (research permit number: MNF/DDR&CB/289/2022–2023, MNF/DDR&CB/1957/2021–2022, Admin/1422/2019–2020).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bopardikar, I., Harris, D.V., Robin, V.V. et al. Comparing visual and acoustic detectability of two coastal cetacean species off Sindhudurg, India, to better inform integrated survey protocol. Sci Rep 15, 31146 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98691-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98691-9