Abstract

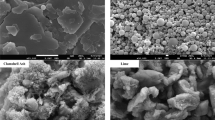

Plasticity properties of fine-grained soils in the form of Atterberg limits are very important inferential properties used for classification and preliminary qualitative assessment of their suitability for any geotechnical engineering applications. Through extensive research, it is well understood that clay mineralogy and soil structure are the main factors that control the Atterberg limits of soils. To further the understanding of the factors influencing the Atterberg limit of soils at the macro level with an insight at the micro level through SEM studies, the present study was taken up using various soil mixtures prepared with extreme clay minerals (Bentonite and Kaolinite), fine sand, and silt (extracted from a natural soil). From the experimental results reported herein, the changes observed in the Atterberg limits as influenced by the variation in the composition of the fractions in the clay-sand-silt mixture may be due to the influence of clay mineral type and the clay structure which are supported by the SEM images.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atterberg limits are very useful plasticity properties of fine-grained soils, which have been popularly used to predict engineering properties through various correlations developed from time to time. The Atterberg limits are influenced by various factors, including the clay mineralogy and soil structure. Understanding these factors is crucial in soil science and more so in geotechnical engineering. Many researchers have carried out extensive studies on the factors influencing and the mechanism/s controlling the Atterberg limits of soils.

It is known that the study of the liquid limit with plasticity index helps us in identifying the clay type present in the soil and classifying fine-grained soils through the plasticity chart. Shrinkage limit is a useful parameter in understanding the large volume change behaviour of soils which takes place when subjected to wet and dry cycles (e.g., earth dams, clay liners, etc.). It is also understood that shrinkage limit can be used for estimating the quantitative change in the volume of soil1. Further, it also helps in assessing the suitability of soil as a construction material in foundations, subgrade of pavements, embankments, and earthen dams.

The influence of the type of clay mineral and soil structure on the value of Atterberg limits and their indices has been reported in the literature2,3,4. Findings from their studies indicate that soil structure has a prominent influence on the liquid limit of kaolinitic soils, whereas, diffuse double layer contributes significantly to the liquid limit of montmorillonitic soils. Polidori5 observed that the liquid limit and plastic limit values of the soil mixtures tested, except those with a low clay percentage, are linked to the respective clay size contents. Recently, Verma and Kumar6 from their study on bentonite admixed with limestone dust and fine sand have reported that liquid limit and plastic limit are primarily controlled by the clay content, marginally by the particle size, and least by the fractions of silt and sand-sized particles.

Yong and Warkentin7 have reported that the shrinkage characteristics of fine-grained soils depend on the type of clay mineral, clay content, mode of geological deposition, and the depositional environment, inferring that shrinkage limit of soils is a function of soil plasticity and soil fabric. As the understanding of the factors influencing the shrinkage limit progressed, it was observed that the shrinkage limit of natural soils is a result of the packing phenomenon, which in turn, is governed by the grain size distribution of soil8. Additionally, they observed that, in pure clays, the fabric also affects shrinkage limit. They also observed that the shrinkage limit is not at all related to the plasticity characteristics of the soil, and shrinkage limit cannot indicate the swelling behaviour of the soil. Further, with the investigation of the shrinkage limit of soil mixtures, Sridharan and Prakash9 confirmed that the shrinkage limit of the soil mixtures is not dependent on plasticity characteristics, and it is primarily governed by the relative grain size distribution of soil. Srikanth and Mishra10 from the results of their study with bentonite-sand mixtures have reported that the sand composition has a notable influence on the shrinkage characteristics. These findings reported by various researchers open up a new direction in understanding the fundamentals of soil behaviour.

Though the past studies have given an understanding of the factors controlling/influencing the Atterberg limits of soils, it was felt there is a need to further the knowledge of the factors controlling the Atterberg limit of soils at the macro level with an insight at the micro level through the SEM studies. Hence, the present study was taken up with a focus on further understanding the mechanism controlling Atterberg limits of soils, using various soil mixtures prepared with extreme clay minerals (Bentonite and Kaolinite), fine sand, and silt (extracted from natural soil). The findings from this study are supported with SEM images.

Materials and methods

Commercially available clays (Kaolinite and Bentonite) with extreme plasticity properties were chosen for the study. These clays were procured and tested for their physical properties. As it was intended to study the influence of soil structure on the Atterberg limits of clay, it was required to have sand and silt introduced to clay in varying proportions to form clay-sand, clay-silt, and clay-sand-silt mixtures. To obtain the silt (size) fraction needed for the study, a natural soil having a sufficient quantity of silt fraction was selected, which was sourced from Kanaswadi, Doddballapur Taluk, Bangalore Rural district, Karnataka state, India. To extract silt from the selected natural soil sample, it was initially oven-dried at 105 °C, and then batches of approximately 10 kg of oven-dried soil was transferred to a drum of 50 L capacity filled with tap water. The soil was allowed to soak in water for 24 h. This soaked soil water mixture was wet sieved using a thin stream of water to pass through 75 μm IS sieve size to separate fines [fraction comprising of silt (size) and clay (size)] from the coarse fraction (sand). The wet sieved fraction of fines was collected in buckets of 25 L capacity. This wet mixture of fines was stirred for approximately 2 to 3 mins and allowed to sediment. After allowing approximately 60 mins of settling, the top supernatant liquid was collected and transferred to another bucket using a jug, thereby separating the clay (size) fraction from the silt (size) fraction. The sedimented portion of wet silt (size) fraction left out in the bucket was then allowed to settle for nearly a day to facilitate settling of the silt (size) fraction at the bottom of the bucket. Later the clear water at the top was siphoned out using a rubber pipe of 10 mm diameter. The left-out slurry was transferred to a steel tray and dried in the sun for at least two days to obtain the silt (size) fraction. The dried silt (size) fraction was stored in big-size polythene covers. This process of extraction of silt (size) fraction was repeated to obtain sufficient quantity as required for the experimental program. Further, to obtain the finesand fraction (< 425 μm and retained on 75 μm) needed for the present study, commercially available river sand (particle size greater than 0.09 mm and less than 0.5 mm) was procured and sieved through 425 μm, which is considered as fine sand as per Bureau of India Standards (SP36). The sieved fine sand fraction was collected in polythene covers and stored for later use.

The selected commercially available clays, the selected natural soil and sand were characterized for their physical and plasticity properties adopting standard procedures as outlined in Bureau of Indian Standards11. The specific gravity of the soil was determined using the density bottle method. The liquid limit of the soil was determined using a cone penetrometer having an apex angle of the cone 30° ± 0.5° and the mass of the plunger along with its components and cone being 80 ± 0.5 g12; and the plastic limit of the soil was determined by rolling thread method. The shrinkage limit test was done using the mercury displacement method. For soil mixture series with kaolinite and kaolinite-coarse fraction, shrinkage pats were air dried for 1–3 days. Whereas, for the bentonite mixture series, the pats were air-dried for 7–15 days, and later they were dried at around 40 °C for 24 h by placing the shrinkage dish along with the pats over the oven, and furthet dried at 110 °C for 24 h by placing it in an oven. This extra care was taken to avoid cracking of shrinkage pats. Grain size analysis was done by wet sieving 300 g of oven-dried soil using a 75 μm sieve. The soil retained on the 75 μm sieve was oven dried and sieved using a set of sieves with a sieve size opening of 4.75 mm, 2.36 mm, 1.18 mm, 600 μm, 425 μm, 300 μm, 150 μm, and 75 μm. The soil passing 75 μm was collected, air dried, and the grain size distribution analysis was performed by the hydrometer method. Figure 1 shows the plots of grain size distribution of various soils (commercially available clay, natural soil, extracted silt, and sand) used in the present study. The physical properties of all the soil materials (namely, clays, natural soil, extracted silt, and fine sand) used in the present study have been summarized in Table 1.

The mineralogical analysis of the soils was performed using an X-ray diffractometer and Cu–kα radiation. The principal clay minerals present in the pure clays and extracted silt are given in Table 1. Typical X-ray diffraction patterns of kaolinite, bentonite, and extracted silt are presented in Fig. 2a–c. The presence of principal clay mineral for all the clay-fine sand-silt mixtures used in the present study was also ascertained indirectly through the Free Swell Ratio (FSR) as defined by Prakash and Sridharan13. FSR has been used as a simple and alternate method of identifying the presence of principal clay minerals present in fine-grained soils. FSR as defined by Prakash and Sridharan13 is the ratio of sediment volume of 10 g of soil (< 425 μm sieve) measured in a 100 ml jar using distilled water to that of kerosene.

Since, it was intended in this study to understand the influence of microstructure on the Atterberg limits, scanning electron microscope images (SEM) of all the clay-fine sand-silt mixtures used in the present study were obtained using VEGA3 TESCAN Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

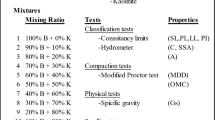

Experimental program

As the main objective of the present research was to study the influence of soil structure and clay mineralogy on the Atterberg limits, an experimental program was formulated to have soil mixtures comprising clay-fine sand-silt mixtures in different combinations and proportions, and the plasticity properties were evaluated. In total, nine clay-sand-silt mixtures were prepared as given in Table 2.

In each of the above series, clay-fine sand-silt mixtures were prepared by using clay fraction, which was varied from 90 to 30%, in intervals of 10%; and coarse fraction in the form of fine sand or silt or fine sand + silt was varied from 10 to 70%. In three series, namely series 3, series 6, and series 9, clay fraction used was a combination of two extreme clay types (Bentonite and Kaolinite) in equal proportions. Additionally, in series 7, 8 and 9, the coarse fraction used was an equal proportion of fine sand and silt. These varied combinations of clay (Kaolinite and Bentonite), fine sand, and silt were prepared to bring out the influence of the soil structure and clay mineralogy on the Atterberg limit of clayey soils.

Results and discussion

The experimental findings from this study done to understand the factors influencing the Atterberg limits are presented and discussed in this section.

Figure 3 is a set of plots of liquid limit versus clay fraction for all the series of clay-fine sand-silt mixtures. From the set of plots in Fig. 3, it can be observed that as the percentage of coarse size fraction increases (or clay reduces), as usually expected, the liquid limit has reduced approximately by 65–70% in the case of B + FS (series-1), K + FS (series 2), B + K + FS (series 3), B + M (series-4), B + K + M (series-6), B + FS + M (series 7), and B + K + FS + M (series 9); whereas, in K + FS + M series (series-8) liquid limit has reduced only by 20%. However, an opposite behaviour of an increasing trend of the liquid limit with an increase in coarse size fraction in the form of silt (or decrease in clay content) is observed in the K + M series (series-5), the increase is approximately 25%. This type of increase in the liquid limit of soil mixtures with the addition of coarse size fraction to pure clay has not been hitherto reported in the literature. This observed behaviour can be explained as follows. From Table 1, it can be observed that the liquid limit values of extracted silt is 75.1%, which is higher than that of kaolinite, which is 44.2%. Hence, in series-5 addition of silt to the kaolinite has led to increase in the plasticity properties of the mixture, thereby increasing the liquid limit. However, this increasing trend of the liquid limit has not be observed for K + M + FS or K + FS series. This is because, fine sand does not have any water holding capacity as compared to silt.

Additionally, It is well known that silt contributes to an open structure14, which in turn probably may increase the water-holding capacity of soil having such an open structure (edge-to-face arrangement or flocculated structure). Hence, the soil mixture with increasing silt addition, probably has led to a change in soil structure to a relatively open fabric, resulting in higher water holding capacity, and higher liquid limit values. This indicates that liquid limit as a water-holding capacity of fine-grained soil is not only influenced by the presence of clay, but also by the soil fabric/structure that promotes its water-holding capacity. This observed behaviour at the macroscopic level can be better explained by the soil structure (as influenced by the clay mineral type) and its changes (as influenced by the addition of silt) observed at the micro-level through the SEM views.

Figure 4a, b are SEM views of pure kaolinite and bentonite respectively. From the SEM views, it can be observed that edge to face arrangement (flocculated structure) of kaolinite (Fig. 4a) is very evident as compared to face to face arrangement (dispersed structure) of bentonite (Fig. 4b). Figure 5a, b are the SEM views for series-4 (which is a mixture of bentonite clay mineral with silt (M) with 10% and 70% M respectively. Figure 6a, b are SEM views for series 5 with similar proportions of 10% and 70% M but with kaolinite clay mineral. From the SEM views shown in Fig. 5a, b, it can be observed that the soil structure has almost remained dispersed with the addition of silt (M) [even up to 70%] to bentonite clay mineral. It has been earlier reported by Sridharan3 that the liquid limit of montmorillonite clay is controlled by the thickness of the diffuse double layer, which in turn results in net repulsive forces. So, for bentonite clay, which has net repulsive forces due to the presence of diffuse double layer (DDL), it has not been possible to reduce the thickness of DDL with the addition of silt, and hence, not been possible to floc the clay particles from near parallel arrangement. However, from Fig. 6a, b, it can be observed that there is an increase in edge-to-face arrangement with increasing addition of silt to kaolinite clay mineral, thus leading to a relatively more flocculated structure. It is well understood and also reported by Sridharan et al.4 that kaolinite clay will have a flocculated structure, which is also evident from the SEM view as shown in Fig. 4a. Additionally, they have reported that inter-particle attraction and repulsive forces have a prominent role in determining the liquid limit of kaolinitic soils. These forces determine the particle arrangement (clay fabric) which in turn regulates the liquid limit. The addition of silt fraction to kaolinite clay will promote interparticle attraction leading to the formation of more flocs, and hence, the observed increase in liquid limit. These micro-level changes observed through SEM views support the macro level changes in the increasing trend of liquid limit for kaolinite-silt series (K + M series) as compared to the decreasing trend of liquid limit for bentonite-silt series (B + M series).

Figure 7 is a set of plots of shrinkage limit versus clay fraction of all series of clay-sand-silt mixtures. It can be observed from the set of plots that, with an increase in coarse size fraction (or decrease in clay) in the soil mixtures, there is an increasing trend of shrinkage limit for B + FS (series-1), B + K + FS (series-3), B + M (series-4), B + K + M (series-6), B + FS + M (series-7) and B + K + FS + M (series-9). It can be observed in series 4, which is a mixture of bentonite with M and series 7, which is a mixture of bentonite with FS and M that the shrinkage limit has increased by 73% with an increase in coarse size fraction (M/FS + M); and for series 1, which is a mixture of bentonite with FS, the shrinkage limit has increased by 160% with increase in coarse size fraction. This substantial increase in shrinkage limit may be due to the change in structure from a highly dispersed structure to relatively open fabric with the addition of coarse size fraction to pure clay mineral (Bentonite). The change in fabric can be observed from Fig. 8a, b, which show the SEM images of bentonite and FS mixture with 10% and 70% FS respectively. Whereas, in K + M (series-5), it can be observed that the values of shrinkage limit have almost remained constant with the addition of silt fraction. This is because, as observed from grain size distribution plot (Figs. 1 and 9), kaolinite clay mineral is having significant fraction of silt (size) (80%). So, further addition of silt fraction to kaolinite, there is no change in the gradation of soil as there is only a parallel shift in the GSD curves (Fig. 9). However, when FS is added along with Silt (M) in equal proportion to kaolinite clay (series-8), there is a decrease in shrinkage limit by 36% with the addition of 70% FS + M. Further, the addition of FS alone to kaolinite clay (Series 2), there is a decrease in shrinkage limit by 58% with the addition of 70% FS. This indicates that the addition of coarse size fraction in the form of FS alone or FS with silt (M) to kaolinite clay has probably improved the soil gradation from a more uniformly graded soil in the case of kaolinite alone to a relatively better-graded soil (Fig. 9). This would have also aided the deflocculation of the clay structure in the soil mixtures, thus leading to a better packing of finer clay fractions in coarser matrix.

Sridharan and Prakash8 proposed that the shrinkage process is a packing phenomenon, and it is dependent on the grain size distribution of the soil. Further, they state that soil with a predominantly flocculant structure results in a higher shrinkage limit, and soil having a predominantly dispersed structure is responsible for a lower shrinkage limit. It is also well known that kaolinite has a predominantly flocculated structure, and hence, addition of coarse fraction (FS + M or FS) to kaolinite might have defloculated the original flocculated structure of kaolinite. This may be the reason for the decrease in shrinkage limit. Figure 10a–d show the schematic representation of the probable fabric (or structure) arrangement of the kaolinite clay alone and the change in fabric that might have occurred when the coarse fraction is added.

A schematic diagram of probable fabric packing of kaolinite clay and with addition of coarse particles (FS + M/ FS alone). a Flocculated structure for kaolinite clay alone. b Increased flocculation of the kaolinite clay mixture with higher percentages of silt. c, d Deflocculated structure for kaolinite with higher percentage of fine sand + silt and fine sand respectively .

Based on the information reported in the literature and the observations from this study, the authors further like to state that, in a clay-coarse size fraction matrix, the factor which is dominant among the two, namely the soil structure or the packing of fine clay fraction in the coarser fraction controls the shrinkage limit of soils, especially this can be observed in clay type having flocculated structure. Thus, for clayey soils having flocculated structure, soil fabric along with packing of soil through improved gradation may also play a significant role in controlling the shrinkage limit of soil mixtures. Similarly, in Figs. 11 and 12a and b, it can be observed that the flocculated structure of the pure clay (Kaolinite) has been altered to a more dispersed structure with the addition of a coarser fraction.

It is generally understood that the shrinkage limit decreases with an increase in the liquid limit or vice versa. The increase in liquid limit may be due to an increase in clay content of soil, and as the clay content increases, the shrinkage limit decreases. However, from Fig. 13, it can be observed that for bentonite series/bentonite with kaolinite series (where the presence of bentonite will have a significant influence on the soil structure) the shrinkage limit decreases with an increase in liquid limit, whereas for the kaolinite series, shrinkage limit distinctly increases with an increase in liquid limit. This observation is similar to that reported by Sridharan et al.4 wherein they observed that for kaolinitic soils an increase in liquid limit was accompanied by an increase in shrinkage limit.

As earlier explained, in the bentonite series, an increase in coarse size fraction may lead to a reduction in repulsive forces, leading to a reduction in the thickness of the diffuse double layer of the clay (Bentonite). This reduction in the thickness of the diffuse double layer would influence changing the soil structure from a dispersed structure to a relatively flocculated structure, thus leading to an increase in shrinkage limit. On the contrary, for soil mixtures with kaolinitic clay (FS/FS + M) alone, addition of coarse fraction to the kaolinite clay (which has a flocculant structure) may probably lead to a reduction in attractive forces and also a better gradation, leading to deflocculation of the soil structure. The reasons for this observed behaviour can be inferred from the information reported by Sridharan et al.4 that for kaolinitic soils, the liquid limit is controlled by interparticle attraction and repulsion forces and the shrinkage limit is a function of soil fabric. Additionally, the shrinkage limit of soil may be the result of the packing phenomenon and is primarily controlled by the relative grain size distribution of the soil reported by Sridharan and Prakash9.

Figure 14 shows the variation of plastic limit versus clay fraction. From this figure, it can be observed that the plastic limit reduces with a reduction in clay content. This is understandable because, as the coarse fraction in the form of FS, M, and FS + M increases in the clay mixture, the plasticity property of the soil mixture reduces, hence, the plastic limit values reduces.

Conclusions

The present study was taken up with the intention of understanding the influence of soil structure and clay mineralogy on Atterberg limits and substantiating the macro-level observations with micro-level studies in the form of SEM views. The important findings from this experimental study are summarised as given below.

In general, the liquid limit of clay mixtures is observed to decrease with an increase in coarse fraction (or decrease in clay fraction). This is similar to that being reported in the literature. However, an exception to this generally reported trend was observed in the present study in the kaolinite-silt series, wherein, the liquid limit was observed to increase with an addition of coarse fraction in the form of silt content. This may probably be due to the increase in open structure (flocculated structure) with the addition of silt fraction. This observed macro level changes was substantiated with SEM views, wherein it was observed that there is an increase in edge to face arrangement of kaolinite clay mixture with the addition of silt. However, for both bentonite and bentonite-kaolinite series, the values of liquid limit have decreased with the addition of a coarser fraction, which is as expected. This may be due to the reduction in the net repulsive force and also a decrease in the thickness of DDL.

As compared to the liquid limit variation, the shrinkage limit of the bentonite series has increased significantly with the addition of coarse fraction, which may be due to the change in the structure of the clay mixture from dispersed to flocculated. Hence, it can be inferred that the soil fabric has a dominant role in controlling the shrinkage limit of montmorillonite soils. However, in the kaolinite series shrinkage limit has decreased with the addition of coarse fraction. The addition of coarse fraction might have aided better gradation which plays a significant role in controlling shrinkage limit. It was earlier reported by Sridharan and Prakash8 that the shrinkage process is a packing phenomenon and is primarily controlled by the relative grain size distribution of soil. This supports the observed shrinkage limit variation with the addition of coarse fraction to kaolinite clay. Additionally, the addition of coarse fraction to kaolinite clay, which has a predominantly flocculated structure, might lead to deflocculation of the clay mineral, and probably may have an added effect to decrease the shrinkage limit.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FSR:

-

Free Swell Ratio

- Gs:

-

Specific gravity

- Ip :

-

Plasticity index

- K:

-

Kaolinite

- Mo:

-

Montmorillonite

- Mu:

-

Muscovite

- NP:

-

Nonplastic

- Q:

-

Quartz

- wL :

-

Liquid limit

- wP :

-

Plastic limit

- wS :

-

Shrinkage limit

References

Nagaraj, H. B. & Sridharan, A. Prediction of co efficient of volume change from index properties, Geopredict. In Proceedings, National symposium on prediction methods in Geotechnical Engineering (IIT Madras, 2005).

Sridharan, A. & Rao, G. V. Mechanisms controlling the liquid limit of clays. In Proceedings, Istanbul Conference on SM and F.E. 1, 75–84 (1975).

Sridharan, A., Rao, S. N. & Murthy, N. S. Liquid limit of montmorillonite soils. Geotech. Test. J. 9 (3), 156 (1986).

Sridharan, A., Rao, S. N. & Murthy, N. S. Liquid limit of kaolinitic soils. Géotechnique 38 (2), 191–198 (1988).

Polidori, E. Relationship between the Atterberg limits and clay content. Soils Found. 47 (5), 887–896 (2007).

Verma, G. & Kumar, B. Statistical analysis of factors influencing the liquid and plastic limits of fine-grained soil mixtures. In Advances in Sustainable Construction Materials: Select Proceedings of ASCM 2020 331–339 (Springer Singapore, 2021).

Yong, R. N. & Warkentin, B. P. Introduction To Soil Behaviour (Macmillan, 1966).

Sridharan, A. & Prakash, K. Mechanism controlling the shrinkage limit of soils. Geotech. Test. J. 21 (3), 240–250 (1998).

Sridharan, A. & Prakash, K. Shrinkage limit of soil mixtures. Geotech. Test. J. Am. Soc. Test. Mater. 23 (1), 3–8 (2000).

Srikanth, V. & Mishra, A. K. Atterberg limits of sand-bentonite mixes and the influence of sand composition. In Indian Geotechnical Conference, 139–145 (2019).

SP-36. Compendium of Indian Standards on Soil Engineering Part-I (Bureau of Indian Standards, 1987).

IS-11196. Specification for Equipment for Determination of Liquid Limit of Soils Cone Penetration Method (Bureau of Indian Standards, 1985).

Prakash, K. & Sridharan, A. Free swell ratio and clay mineralogy of fine-grained soils. Geotech. Test. J. 27 (2), 220–225 (2004).

Assallay, A. M., Rogers, C. D. F., Smalley, I. J. & Jefferson, I. F. Silt: 2–62 µm, 9–4 φ. Earth-Sci. Rev. 45, 61–88 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors like to acknowledge Chikkanna for identifying and supplying the natural silty soil from which silt was extracted and used in this experimental study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology and supervision: N.H.B.Investigation, and writing first draft: B. KWriting- Review & final version: N.H.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhavya, K., Nagaraj, H.B. Influence of soil structure and clay mineralogy on Atterberg limits. Sci Rep 15, 15459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98729-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98729-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of Soil Structure on Rate-Dependent Consolidation of Clayey Soils

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)