Abstract

This research assesses multiple predictive models aimed at estimating disintegration time for pharmaceutical oral formulations, based on a dataset comprising nearly 2,000 data points that include molecular, physical, compositional, and formulation attributes. Drug and formulation properties were considered as the inputs to estimate the output which is tablet disintegration time. Advanced machine learning methods, including Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), Relevance Vector Machine (RVM), and Sparse Bayesian Learning (SBL) were utilized after comprehensive preprocessing involving outlier detection, normalization, and feature selection. Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) was utilized for model optimization to obtain optimal combinations of hyper-parameters. Among the models, SBL stood out for its superior performance, achieving the highest R² scores and the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) error rates in both the training and testing phases. It also demonstrated robustness and effectively avoided overfitting. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis provided valuable insights into feature contributions, highlighting wetting time and sodium saccharin as key factors influencing disintegration time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solid dosage oral formulation is the most commonly used method of drugs administration due to its advantages compared to other formulations. The attractive benefits of solid dosage formulations have resulted in the production of the majority of medications in solid oral formulations such as tablets and capsules1,2. As such, oral route of administration is the prevailing method of drug usage by patients. The most common form of oral solid formulation is tablet which can be manufactured by granulation or direct compaction methods3,4. The drug release of tablet is highly dependent on process variables such as compaction force, materials properties such as density, flowability, and the tablet physical properties such as hardness, disintegration time, excipient type, binder, etc5,6.

Since the drug release of tablet is important in delivery of API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) to patients in a controlled and efficient manner, the formulation of tablets must be precisely designed in order to obtain the best tablets with the desired characteristics such as sustained released tablets7,8. On the other hand, for immediate-release tablets, the structure of tablet and design are different than controlled-release formulations. For the immediate-release formulations, disintegration plays an important role, and proper disintegrants must be added to the formulation for enhancing the release of API to patients9,10. Indeed, the disintegrant component facilitates the process of breaking tablet into smaller particles for the immediate-release formulas10. Tablet hardness can be correlated to the formulation properties such as particle size, excipient content, excipient type, binder content, etc. However, computational models are useful for evaluating tablet disintegration time versus formulation properties.

Given the complex nature of tablet disintegration in liquid phase and dependency of release rate on the disintegration time, and also considering large samples to be analyzed, data-driven models such as machine learning (ML) models can be employed in evaluating disintegration time for immediate-release solid dosage oral formulations as a function of formulation parameters. Through the analysis of complex, high-dimensional datasets, ML has become a critical instrument for predictive modeling and the identification of latent relationships among variables. In numerous fields, particularly in pharmaceuticals, ML has revolutionized the analysis of complex systems, facilitating the prediction and optimization of essential parameters that are vital to performance and outcomes11,12,13. Within this context, disintegration time, a vital characteristic of pharmaceutical formulations, provides an ideal application for ML techniques, given its dependence on a wide array of molecular, physical, and compositional features.

This study focuses on three advanced ML methods: Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), Sparse Bayesian Learning (SBL), and Relevance Vector Machine (RVM). These models were selected for their complementary strengths in regression tasks. BRR combines Bayesian inference with ridge regression, mitigating issues like multicollinearity and overfitting while offering probabilistic insights into model predictions. SBL, with its hierarchical Bayesian framework, excels in identifying sparse solutions, automatically emphasizing relevant features in high-dimensional datasets. RVM, known for its sparse representation, provides interpretable results by selecting a minimal set of relevance vectors, thus balancing accuracy and computational efficiency. Together, these models encompass robustness, sparsity, and interpretability, making them well-suited for the predictive challenges in this study.

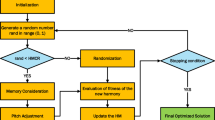

To enhance model performance, Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) was employed for hyperparameter tuning. GWO efficiently explores the search space for optimal parameter settings, ensuring that the models achieve their best predictive capabilities. This integrative approach of combining advanced ML models with bio-inspired optimization highlights the methodological rigor applied in this research.

The primary contribution of this work lies in its comprehensive approach to predictive modeling of disintegration time, which integrates advanced preprocessing, model selection, and interpretability frameworks. The application of SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values further enriches the study by providing detailed insights into feature contributions, enabling better understanding and optimization of formulation properties. The goal is to develop a solid framework for using ML in disintegration time modeling for this research.

Materials and methods

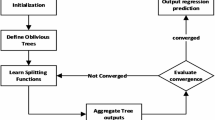

The methodology employed in this research involves a multi-step approach combining data preprocessing, feature selection, and advanced ML techniques for predictive modeling. Initially, outliers were detected and removed using the SOD method, followed by normalization through Min-Max scaling. RFE was then employed for feature selection. Subsequently, BRR, SBL, and RVM models were developed and evaluated for prediction accuracy. The optimization process was further enhanced using GWO to fine-tune the models and improve performance. Figure 1 illustrates the overall methodology as a flowchart, highlighting each phase from data preprocessing to model evaluation. All ML computations and evaluations were conducted using Python programming language, employing libraries such as scikit-learn, numpy, matplotlib, and SHAP for model development, evaluation, and interpretation.

Dataset and pre-processing

The dataset focuses on disintegration time as the output variable and includes nearly 2,000 data points which have been obtained from the previous publication on generation of the large dataset for prediction of tablet disintegration time versus formulation properties for immediate-release formulations14. It comprises a diverse set of input variables, grouped into molecular properties (such as molecular weight and hydrogen bond counts), physical properties (like hardness and friability), excipient composition (including microcrystalline cellulose and magnesium stearate), and formulation characteristics (e.g., wetting time and bulk density). Together, these attributes capture chemical, physical, and compositional factors that affect disintegration time14.

Figure 2 illustrates histograms of the distributions for selected features within the dataset. These visualizations offer insight into the variability and range of key input variables, highlighting patterns such as skewness, central tendency, and the presence of potential outliers. By depicting the frequency of data points across different bins, the histograms provide a foundational understanding of the dataset’s structure, aiding in the interpretation of subsequent analysis and modeling steps. This representation is integral to identifying preprocessing needs, such as normalization or feature scaling, to optimize the dataset for ML applications.

Pre-processing is a critical step to enhance the quality and performance of ML models. Initially, outliers in the dataset were detected using the Subspace Outlier Detection (SOD) method, ensuring that extreme data points do not skew the results. To normalize the input features, we applied min-max scaling. Finally, for feature selection, we used Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE).

-

Outlier detection: SOD method is designed to identify outliers across multiple subspaces in a high-dimensional feature space. An outlier is a data point that markedly deviates from the reference hyperplane15,16. For a point p, the outlier score is found in this way:

In this equation, \(\:H\left(R\left(p\right)\right)\) represents the hyperplane formed by the reference set \(\:R\left(p\right)\). Furthermore, \(\:{v}_{R\left(p\right)}\) denotes the vectors that define the subspace of the reference set, emphasizing the most relevant features identified by the least variation.

-

Normalization: Min-Max normalization is a feature scaling method that adjusts data by rescaling each feature to a known domain, such as [0, 1]. This method balances the contribution of all features to the model while retaining the relationships between data points17.

-

Feature Selection: RFE is a method for selecting features that systematically eliminates the least significant features by evaluating the performance of a model. The process involves fitting a model, assessing the importance of features, and systematically removing the least significant ones until the target feature size is achieved, thereby enhancing both model efficiency and interpretability18,19.

Bayesian ridge regression (BRR)

BRR is a resilient statistical model that integrates Bayesian principles with ridge regression for the analysis of regression issues. The approach integrates the prior distribution with the likelihood function to derive the posterior distribution, subsequently facilitating the estimation of model parameters and enabling predictive analysis. Adding a regularization term improves the ability of the model to generalize, by reducing overfitting20.

The hyperparameter \(\:{\upalpha\:}\) controls the range, and the mean is zero. This means that in BRR, the regression coefficients are thought to have a normal distribution. The likelihood of the data is similarly modeled using a Gaussian distribution, where the mean is determined by a linear regression model and the variance is regulated by another hyperparameter \(\:{\uplambda\:}\). The primary aim is to determine the most probable values of the regression coefficients (\(\:{\upbeta\:}\)) by integrating the observed data with the prior distributions. The posterior distribution of \(\:{\upbeta\:}\) is represented as21:

where, \(\:{\Sigma\:}\) represents the covariance matrix of the posterior distribution and \(\:{\upmu\:}\) denotes the mean vector. These quantities are computed through Bayesian inference, as outlined in the equations below22:

In these equations, \(\:{X}^{T}y\) stands for the product of the transpose of the input matrix with the response vector, \(\:{X}^{T}X\) indicates the self-product of the transposed input matrix, and I is the identity matrix23. This approach facilitates the seamless incorporation of prior knowledge and experimental data to improve the estimation of \(\:{\upbeta\:}\).

Sparse bayesian learning (SBL)

SBL is a probabilistic framework designed to identify sparse solutions in regression tasks, particularly with high-dimensional data. The major strength of SBL is its unique characteristic of performing feature selection where it learns to choose the most important features by enforcing the model parameters to be sparse. This is achieved through the application of a hierarchical Bayesian approach, where priors are carefully chosen to enforce sparsity24,25.

In SBL, the regression weights (w) are modeled using a Gaussian prior, where each weight is associated with a hyperparameter (\(\:{{\upalpha\:}}_{i}\)) that controls its variance. This structure encourages the model to shrink many weights to near zero, effectively removing irrelevant features. The likelihood of the data is modeled using a Gaussian distribution, similar to BRR, with the mean determined by the linear model and variance governed by a hyperparameter (\(\:{\upbeta\:}\)).

The posterior distribution of the weights is established by integrating the likelihood with the priors via Bayesian inference. The posterior’s mean and covariance are expressed as follows24:

Here, \(\:{\Phi\:}\) stands for the design matrix of input features, A is a diagonal matrix of the hyperparameters \(\:{{\upalpha\:}}_{i}\), and S represents the covariance matrix of the posterior.

Relevance vector machine (RVM)

RVM is a sparse Bayesian model for both classification and regression, offering probabilistic predictions while maintaining a sparse representation. In contrast to Support Vector Machines (SVM), which typically necessitate a large number of support vectors, RVM attains sparsity through the selection of a limited subset of data points referred to as relevance vectors. This characteristic enhances the model’s interpretability and reduces computational complexity during prediction26,27.

In RVM, the target variable t is modeled as a linear combination of basic functions applied to the input features x, plus Gaussian noise28:

where \(\:{\upvarphi\:}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) represents the basis function, \(\:w\) is the weight vector, and \(\:{\epsilon}_{i}\) denotes Gaussian noise with variance \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}^{2}\) and mean equal to 0. A zero-mean Gaussian prior is placed over the weights \(\:w\), encouraging sparsity by shrinking most weights towards zero.

The posterior distribution of the weights is calculated through the product of the likelihood function and the prior distribution by the use of Bayes’ theorem. The resulting posterior mean \(\:w\) and covariance matrix \(\:{\Sigma\:}\) are given by28:

Here, \(\:{\Phi\:}\) is the design matrix of basis functions applied to the input data, and \(\:{\upalpha\:}\) stands for a vector of hyperparameters controlling the sparsity of the weights.

The hyperparameters \(\:{\upalpha\:}\) and the noise variance \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}^{2}\) are iteratively optimized through evidence maximization, a process that ensures only the most relevant vectors remain in the model.

Grey Wolf optimization (GWO)

The GWO is a meta-heuristic optimization method drawn from the hunting behavior of wolves. It models a pack with four types of wolves: alpha, beta, delta, and omega. Each wolf is denoted by a vector of decision variables, signifying its location in the search space. The search mechanism in the GWO algorithm is determined by the locations of the wolves in the pack. Each wolf modifies its location based on its own position as well as the positions of other pack members. This strategy enables the pack to progressively refine its search for the optimal solution29,30.

The equation for modifying the position of each wolf is articulated as follows:

where \(\:\overrightarrow{C}\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{A}\) stand for coefficient vectors, while \(\:\overrightarrow{{r}_{1}}\) denotes a random vector. The vector \(\:\overrightarrow{D}\) denotes the distance, while \(\:\overrightarrow{{x}_{i}}\left(t\right)\) represents the position of the i-th wolf during the t-th iteration. Both the distance vector and the coefficient vectors are updated at every step based on the wolves’ respective positions.

Results and discussion

The results of ML modeling are presented based on the application of BRR, SBL, and RVM models on the processed dataset. An 80 − 20 train-test split was employed to evaluate the models, ensuring a robust assessment of their predictive performance. The training set, constituting 80% of the data, was utilized for model development, whereas the remaining 20% functioned as the test set to assess model generalization. The performance metrics include R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), offering a comprehensive comparison of the models’ accuracy. This section presents detailed results, including performance metrics, error rates, and visualizations of predicted versus actual values. The findings illustrated in Tables 1 and 2, along with Figs. 3 and 4, and 5, emphasize the relative efficacy of BRR, SBL, and RVM.

SBL’s performance was remarkable, with R² of 0.980 for the training phase and 0.960 for the testing phase, indicating strong consistency between the two phases. In contrast, BRR and RVM showed lower test R² scores of 0.872 and 0.918, respectively, indicating that SBL generalized better and avoided overfitting. The conclusion is strengthened by the fact that SBL has a mean cross-validation R² score of 0.978 and a very low standard deviation of 0.0014, which shows that it is consistent across data folds. The cross-validation results showed that BRR and RVM had the highest standard deviations.

SBL achieved the lowest error metrics, with the smallest RMSE and MAPE in both the training and testing phases. Notably, its test RMSE was 10.07, and its MAPE was 12.08%, significantly outperforming BRR and RVM. These results indicate that SBL provided more accurate predictions with less deviation from actual values.

Visual analysis from Figs. 3 and 4, and 5 further supports this. BRR (Fig. 3) and RVM (Fig. 5) showed significant variance in their predictions, particularly at the extremes. In contrast, SBL’s plot (Fig. 4) exhibited a near-perfect alignment of predicted and actual values, confirming its superior accuracy.

SBL outperformed BRR and RVM in terms of accuracy, error reduction, and generalization, as evidenced by high R² scores, low error metrics, and consistent cross-validation results. Unlike BRR and RVM, SBL avoided overfitting while delivering precise predictions across varying data ranges. Thus, SBL is concluded to be the most reliable and effective model for predicting disintegration time in this study.

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is an effective instrument for understanding ML models by measuring the influence of each feature on a prediction. It assigns SHAP values to features based on cooperative game theory, ensuring fair and consistent attribution of influence. Figure 6, the SHAP summary plot, ranks features by their importance and shows their effects on model predictions, with each dot representing an instance in the dataset. The x-axis shows SHAP values, which show how much a feature moves the prediction up or down. The value of each feature is highlighted by color, which makes it easy to see how the model works and how the features interact. The importance of wetting time on the top is related to the importance of wetting tablet by the liquid phase which would enhance the rate of disintegration as the liquid can penetrate the tablet pores and facilitate the disintegration phenomenon of tablets. Indeed, the rate of liquid phase mass transfer inside the tablet is a key parameter which should be controlled in order to control the rate of tablet disintegration.

Figure 7 shows how the expected model output changes with variations in wetting time. It shows a clear trend whereby, depending on its value, wetting time greatly affects the disintegration time as it changes. Figure 8 illustrates the effect of sodium saccharin content and shows its particular contribution to the expected disintegration time of tablets. The visualization emphasizes how changes in sodium saccharin concentration, providing a detailed understanding of its role in model predictions. This observation could be attributed to the binding effect of sodium saccharin in the formulation which can enhance the disintegration time of tablets. As seen, increasing sodium saccharin content up to 4% in the formulation increases the disintegration time of tablet, while it has no significant effect above this value which could be attributed to the influence of other formulation properties which dominate the disintegration time above this threshold.

Together, these figures offer a granular understanding of how individual features independently drive predictions, which is essential for interpreting model behavior and optimizing formulations. The tablets with desired disintegration time can be manufactured by considering the predetermined input parameters based on the developed ML models.

Figure 9 shows the combined effect of wetting time and sodium saccharin content on the predicted disintegration time. The plot illustrates how variations in these two features interact to influence the output. The wetting time is shown on the x-axis, the levels of sodium saccharin are shown on the y-axis, and the predicted disintegration time is shown on the z-axis (or color gradient). This 3D or contour-like visualization highlights specific regions where the interplay of these variables either accelerates or slows down disintegration. For instance, low wetting time coupled with high sodium saccharin would correspond to faster disintegration, whereas other combinations could have a neutral or inverse effect.

Conclusion

This study evaluated BRR, SBL, and RVM models for predicting pharmaceutical tablet disintegration time using a comprehensive dataset encompassing molecular, physical, and compositional features. With high R2, low RMSE and MAPE, and consistent cross-validation results, SBL demonstrated strong predictive accuracy and generalizability. SHAP analysis also revealed sodium saccharin and wetting time to be key factors influencing disintegration time. Providing a powerful tool for formulation optimization, SBL’s robustness and utility in both prediction and feature interpretation are highlighted in these insights. This work shows generally the effectiveness of SBL as a predictive and interpretative tool in pharmaceutical modeling since it provides a route to better formulation design and better knowledge of disintegration dynamics. This work could be used as a starting point for future studies which might examine how credibility of predictions may be improved through combination of different optimization methods or hybrid models.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lee, Y. Z. et al. Formulation of oily tocotrienols as a solid self-emulsifying dosage form for improved oral bioavailability in human subjects. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 76, 103752 (2022).

Hummler, H. et al. Esophageal transit of solid oral dosage forms – impact of different surface materials characterized in vitro and in vivo by MRI in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 203, 106926 (2024).

Huang, Y. S. et al. Real-Time monitoring of powder mass flowrates for Plant-Wide control of a continuous direct compaction tablet manufacturing process. J. Pharm. Sci. 111 (1), 69–81 (2022).

Capece, M., Borchardt, C. & Jayaraman, A. Improving the effectiveness of the Comil as a dry-coating process: enabling direct compaction for high drug loading formulations. Powder Technol. 379, 617–629 (2021).

Manna, S. et al. Characterization of Taro (Colocasia esculenta) stolon polysaccharide and evaluation of its potential as a tablet binder in the formulation of matrix tablet. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 280, 135901 (2024).

Mizobuchi, S. et al. Preparation and characterization of the ground mixture of rebamipide commercial tablets and hydroxypropyl Cellulose-SSL by ball-milling: application to the dispersoid of mouthwash suspension. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 206, 114584 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. Development and in vitro-in vivo evaluation of a novel sustained-release tablet based on constant-release surface. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 105, 106603 (2025).

Liu, T. et al. Further enhancement of the sustained-release properties and stability of direct compression gel matrix bilayer tablets by controlling the particle size of HPMC and drug microencapsulation. Powder Technol. 448, 120256 (2024).

Zaheer, K. & Langguth, P. Designing robust immediate release tablet formulations avoiding food effects for BCS class 3 drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 139, 177–185 (2019).

Jange, C. G., Wassgren, C. R. & Ambrose, K. The significance of tablet internal structure on disintegration and dissolution of Immediate-Release formulas: A review. Powders 2 (1), 99–123 (2023).

Zhong, S. et al. Machine Learning: New Ideas and Tools in Environmental Science and Engineering55p. 12741–12754 (Environmental Science & Technology, 2021). 19.

Javid, S. et al. Machine Learning & Deep Learning Tools in Pharmaceutical Sciences: A Comprehensive Review (Intelligent Pharmacy, 2025).

Pouyanfar, N. et al. Machine learning-assisted rheumatoid arthritis formulations: A review on smart pharmaceutical design. Mater. Today Commun. 41, 110208 (2024).

Momeni, M. et al. Dataset development of pre-formulation tests on fast disintegrating tablets (FDT): data aggregation. BMC Res. Notes. 16 (1), 131 (2023).

Kriegel, H. P. et al. Outlier detection in axis-parallel subspaces of high dimensional data. in Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining: 13th Pacific-Asia Conference, PAKDD 2009 Bangkok, Thailand, April 27–30, 2009 Proceedings 13. Springer. (2009).

Fernández, Á., Bella, J. & Dorronsoro, J. R. Supervised outlier detection for classification and regression. Neurocomputing 486, 77–92 (2022).

Henderi, H., Wahyuningsih, T. & Rahwanto, E. Comparison of Min-Max normalization and Z-Score normalization in the K-nearest neighbor (kNN) algorithm to test the accuracy of types of breast Cancer. Int. J. Inf. Inform. Syst. 4 (1), 13–20 (2021).

Priyatno, A. M. & Widiyaningtyas, T. A systematic literature review: recursive feature elimination algorithms. JITK (Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan Dan. Teknologi Komputer). 9 (2), 196–207 (2024).

Escanilla, N. S. et al. Recursive feature elimination by sensitivity testing. in. 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). 2018. IEEE. (2018).

Bishop, C. M. & Nasrabadi, N. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning Vol. 4 (Springer, 2006).

Williams, P. M. Bayesian regularization and pruning using a Laplace prior. Neural Comput. 7 (1), 117–143 (1995).

Kruschke, J. K. Bayesian data analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cogn. Sci. 1 (5), 658–676 (2010).

Obaidullah, A. J. & Mahdi, W. A. Computational intelligence analysis on drug solubility using thermodynamics and interaction mechanism via models comparison and validation. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 29556 (2024).

Tipping, M. E. Sparse bayesian learning and the relevance vector machine. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 1 (Jun), 211–244 (2001).

Faul, A. & Tipping, M. Analysis of sparse bayesian learning. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 14 (2001).

Tipping, M. The relevance vector machine. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 12 (1999).

Jabbari, M. R., Dorafshan, M. M. & Eslamian, S. Relevance Vector Machine (RVM), in Handbook of Hydroinformatics p. 365–384 (Elsevier, 2023).

Tzikas, D. G. et al. A tutorial on relevance vector machines for regression and classification with applications. EURASIP News Letter. 17 (2), 4 (2006).

Rezaei, H., Bozorg-Haddad, O. & Chu, X. Grey wolf optimization (GWO) algorithm. Advanced optimization by nature-inspired algorithms, : pp. 81–91. (2018).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey Wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Groups Project under grant number (RGP.2/559/45).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.: Writing, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Resources, Software.U.H.: Writing, Validation, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghazwani, M., Hani, U. Prediction of tablet disintegration time based on formulations properties via artificial intelligence by comparing machine learning models and validation. Sci Rep 15, 13789 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98783-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98783-6