Abstract

This study examines the factors driving heavy metal pollution in karst soils and assesses the associated environmental risks. Using a representative karst depression in Guangxi as a case study, we measured soil concentrations of arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and zinc (Zn). These concentrations were analyzed in relation to soil physicochemical properties, morphology, and geological factors to understand pollution dynamics and migration patterns. The findings highlight As as the dominant contaminant, primarily existing in a highly mobile, reduced form. Further analysis shows that its mobility is strongly influenced by soil pH and available phosphorus (AP), emphasizing the interplay between soil chemistry and pollutant behavior. The study area, dominated by limestone strata, experiences changes in soil oxidative conditions due to rainfall, which significantly influence As accumulation and migration. The presence of abundant iron and manganese oxides further amplifies these effects. According to the Hakanson index, As contamination in surface soils presents a high ecological risk to the surrounding environment. Microbial analysis reveals a positive correlation between Proteobacteria and both the total concentration and chemical forms of As. These bacteria demonstrate resistance to As and contribute to increased residual As content, thereby reducing its toxicity and mobility. Additionally, Proteobacteria thrive in As-contaminated soils with high pH and low nutrient levels, highlighting their potential for bioremediation. This positions Proteobacteria as a promising microbial group for managing As pollution in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of industry in China, the improper disposal of industrial waste has become a major source of heavy metal contamination in soils. Heavy metals in soil are characterized by their concealment, persistence, and carcinogenicity. They can be transmitted to the human body through water, air, and plants, potentially causing heavy metal poisoning and leading to serious health issues such as cancer, restrictive lung disease, and ischemic heart disease1,2,3. Furthermore, excessive heavy metal accumulation in soil can disrupt its fundamental structure and degrade the surrounding ecological environment4,5. The variation in soil heavy metal concentrations is also influenced by soil physicochemical properties (e.g., pH, organic matter, available phosphorus, total nitrogen)6,7, as well as its morphology8. Karst regions represent a unique and fragile ecosystem characterized by complex geological conditions and limited capacity for pollution tolerance and self-remediation. Consequently, anthropogenic activities can significantly degrade these ecosystems9. The lithology of the karst area is predominantly composed of carbonate rocks. Due to secondary enrichment processes during soil formation and the dual impact of metal oxide adsorption, significant concentrations of heavy metals accumulate in the soil, resulting in elevated levels10. Therefore, it is significant to evaluated the ecological risk and influence factor in soil heavy metals in karst areas.

Heavy metals in soil can significantly influence microbial communities. Research by Abdu et al.11 shows that elevated heavy metal concentrations reduce microbial biomass, diversity, and activity. Additionally, Wang et al.12identified As as a key driving factor in shaping microbial community composition across different land-use types. The negative effects of heavy metals on microorganisms are often linked to microbial responses that vary depending on the specific type of heavy metal13. Moreover, Chun et al.14 used ecological network analysis to reveal that while heavy metals can disrupt microbial structures, microbes may also contribute to heavy metal bioremediation. This duality provides valuable insights for developing bioremediation strategies for contaminated soils. Understanding the role of resistant microorganisms in mitigating heavy metal impacts offers promising avenues for advancing soil remediation efforts.

Due to the unique characteristics of karst regions, studies specifically addressing heavy metal pollution in these areas remain limited. In particular, there is a lack of research on the concentrations, migration, and distribution of heavy metals in karst soils, as well as their impact on surrounding microbial communities. To investigate the migration of heavy metal pollution and its effects on microbial communities, this study focuses on a contaminated karst soil site in Guangxi, China. It explores the interrelationships among soil physicochemical properties, total and speciated heavy metal content, and microbial community structures, aiming to clarify the ecological risks associated with heavy metal pollution and provide theoretical support for the remediation of similar karst soils.

Materials and methods

Overview of the study area

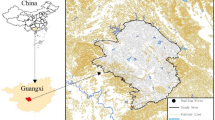

The study area is located east of an arsenic plant in a city in Guangxi Province (106°34’–109°09’ E, 23°41’–25°37’ N) and lies upstream of a water supply source(Fig. 1.). The region features a triangular karst peak-cluster depression, with limestone and Permian formations as the dominant bedrock. The area has a subtropical monsoon climate, characterized by mild temperatures and abundant rainfall. Summers are hot and humid due to tropical maritime air currents, with frequent heavy rainfall, while winters are dry and cold under the influence of northern air masses. The average annual precipitation is unevenly distributed, with more than 80% occurring between April and October. The region’s long-term average temperature is 20.3 °C, with an annual evaporation of 1,095.6 mm and an average relative humidity of 79%.Sample Collection.

Geographic location of the study area and map of sampling sites(Map was taken by a drone and generated with software DJI Terra 3.7.0.https:/terra-1-g.dicdn.com/851d20f7b9f64838a34cd02351370894/D11%20Terra/software/D11%20Terra%203.7.0.exe).

Sample collection

Based on field observations and previous studies, the soil in the study area is contaminated with a mixture of heavy metals, primarily As and Cd) due to the leaching of pollutants from the former arsenic plant located upstream. Among these, arsenic pollution is the most severe15,16.In this study, field sampling was conducted using a random quadrat method. At each sampling site, a 2 m × 2 m quadrat was established to collect surface soil samples. Due to the absence of construction drilling in the study area, vertical soil samples could not be obtained. The collected soils were predominantly yellow, yellow-brown, or black sandy loam or clay. Surface debris was removed before collecting approximately 20 g of soil from a depth of 0–20 cm. The samples were thoroughly mixed, sealed in labeled bags, and collected from 12 locations (Fig. 1.). Each soil sample was divided into two portions: one for analyzing soil physicochemical properties and heavy metal concentrations, and the other, stored in a 100 ml centrifuge tube, for microbial analysis.

Determination of soil contaminants and physicochemical properties

Heavy metal concentrations in the soil were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, PE NexION 350X, USA). For total heavy metal analysis, 0.1 g of soil (sieved to 100 mesh) was digested in 6 mL of aqua regia (HCl: HNO₃ = 3:1) in a 100 mL conical flask and heated on a hot plate before filtration and analysis17. The speciation of heavy metals was determined using the BCR sequential extraction method. A 1 g soil sample (sieved to 100 mesh) was subjected to four extraction steps: (1) exchangeable fraction (F1) using 0.11 mol·L−1 acetic acid, (2) reducible fraction (F2) using 0.5 mol·L−1 hydroxylamine hydrochloride, (3) oxidizable fraction (F3) using hydrogen peroxide digestion followed by 1.0 mol·L−1ammonium acetate extraction, and (4) residual fraction (F4) using a mixed acid solution (HCl-HNO₃-HF-HClO). ICP-MS was used to determine heavy metal concentrations in each fraction18. Soil pH was measured using a pH meter in a 1:2.5 soil-to-water suspension (10 g soil, sieved to 10 mesh)19. Available phosphorus (AP) was extracted with ammonium fluoride-hydrochloric acid for acidic soils and sodium bicarbonate for neutral and calcareous soils. AP was then quantified using a UV spectrophotometer (L5S/L5) at different wavelengths20. Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using an automatic Kjeldahl analyzer (K-375, Büchi, Switzerland) after digestion in a pre-set digestion furnace21. Organic matter (OM) was analyzed by the potassium dichromate-sulfuric acid titration method, where 0.3 g of air-dried soil (sieved to 10 mesh) was digested with 10 mL of potassium dichromate-sulfuric acid solution, heated in a water bath, and titrated with ferrous sulfate until the color changed from orange-yellow to blue-green and finally to reddish-brown. Soil microbiological measurements22.

Soil microbial analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples using the Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) or Sodium dodecyl sulfate(SDS)method. DNA samples were then diluted to 1 ng·µL−1 with sterile water. For sequencing, the diluted genomic DNA served as the template. Specific primers with barcodes were used based on the selected sequencing region, and PCR amplification was performed using the Phusion®High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix with GC Buffer (New England Biolabs) and a high-fidelity enzyme to ensure accuracy and efficiency. The primers targeted the 16 S V4 region (515 F and 806R), The corresponding primer sequences are GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA and GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT. After sequencing, sample data were demultiplexed based on barcode and primer sequences. The barcode and primer sequences were trimmed, and paired-end reads were merged using FLASH23to generate raw tags. These raw tags were then filtered using fastp to obtain high-quality clean tags24. To ensure data integrity, chimera sequences were identified by comparing tags against a reference database and subsequently removed, yielding the final set of effective tags for downstream analysis25,26.

Data analysis

The potential ecological risk index method proposed by Swedish scientist Hakanson was employed to calculate the total concentrations of heavy metals in the soil from a sedimentological perspective. This approach was used to assess the environmental risk posed by heavy metals to the karst soil and the surrounding ecosystem. Individual Heavy Metal Potential Hazard Index using the following Eq. (1).

Multiple Heavy Metal Potential Hazard Indices using the following Eq. (2).

Where: Ci represents the measured concentration of heavy metals in the soil sample, expressed as the total amount of heavy metals (mg·kg−1). Bi denotes the background concentration of the corresponding heavy metal in soil (mg·kg−1)27. Ti is the toxicity coefficient for each heavy metal (As = 10, Zn = 1, Cd = 30, Pb = 5).

Using Spearman correlation analysis and heat maps, we examine the relationships among total heavy metal concentrations, their chemical forms, and soil physicochemical properties. The Hakanson index is applied to evaluate potential ecological risks, while Spearman correlation and Redundancy Analysis (RDA) are employed to explore interactions between soil physicochemical properties, heavy metal concentrations, and microbial communities.Data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2016, and graphs were generated with Origin 2021. Based on the measurement data, concentration distribution maps were created using the inverse distance weighting (IDW) method in ArcGIS 10.8.1.

Results

Analysis of basic soil properties

The physicochemical properties and total concentrations of heavy metals in the study area’s soil are presented in Table 1. Soil pH ranged from 4.80 to 6.72, indicating an overall acidic nature. AP ranged from 1.66 to 16.07 mg·kg−1, OM from 7.83 to 45.13 g·kg−1, and TN from 0.58 to 2.04 g·kg−1. The generally low concentrations of OM, TN, and AP suggest that the soil is nutrient-poor. The background values of the four heavy metals in the karst region are higher than the national soil background values, indicating that the study area is a geochemical high-background region for heavy metals. The extent to which a contaminant exceeds the risk screening value is typically referred to as the exceedance factor. As exhibited a maximum exceedance of 27 times the threshold, with concentrations at over 50% of the sampling sites surpassing the standard limit. Zn and Pb concentrations did not exceed the threshold values, with CV of 34.58% and 46.58%, respectively, indicating moderate variability. Although Cd exceeded the screening value at all sampling sites, only its maximum concentration of 3.2 mg·kg−1 surpassed the local background level. The CV of Cd was 55.11%, suggesting high variability. All physicochemical properties followed an approximately normal distribution, whereas the distributions of As, Zn, and Cd were strongly positively skewed. Only Pb exhibited a distribution close to normal.

Spatial distribution of heavy metals in soil

As shown in Fig. 2; Table 1, As pollution in the study area is unevenly distributed, with a general trend of migration from higher to lower elevations. The contamination is primarily concentrated in the low-lying northeastern region. The spatial distribution patterns of Zn, Cd, and Pb are similar, all exhibiting a “light in the middle, heavy at both ends” pattern, with significant accumulation observed at both high and low elevations. Among these, Zn and Cd share the most similar distribution, with their highest concentrations found at the highest elevations. In contrast, Pb shows its peak concentration at lower elevations. These patterns suggest that Zn and Cd may be recent external pollutants that have not yet migrated, whereas Pb appears to have already moved downstream within the soil profile.

Soil heavy metal forms

The total concentrations and speciation of the four heavy metals are shown in Fig. 3a–d. Each speciation exhibits different mobility, toxicity, and bioavailability in soil. The first three fractions—F1, F2, and F3—are considered bioavailable forms, exhibit gradually decreasing mobility and toxicity. In contrast, F4 represents elements incorporated within silicate mineral lattices, making it the most stable form28,29. As shown in Fig. 3, the dominant species of As, Cd, and Pb in the soil is F2, which is characterized by high mobility and toxicity. Notably, Cd exhibits the highest combined proportion of F1 and F2 species. Although its overall concentration is relatively low, the potential risk of migration cannot be overlooked. In contrast, Zn is primarily present in the F4 fraction, which is relatively stable in the environment.

Correlation between total heavy metals, forms, and physicochemical properties in soil

The correlation between the total concentrations of heavy metals and their chemical forms was investigated (Fig. 4, Table S1). The results indicate that all As species are significantly positively correlated with total As, with the F2 fraction showing the strongest correlation, suggesting that As concentrations are strongly influenced by its more mobile form. For Zn, the F4 fraction exhibits the highest and most significant positive correlation with total Zn, indicating it is the predominant form. The F1 and F2 fractions of Cd show the strongest correlations with total Cd, and these two forms also account for the highest proportion across all sampling sites. For Pb, the F2 fraction is the dominant form at all sites and it also shows the strongest correlation with total Pb.

Spearman’s correlation heat map of heavy metal morphology with physico-chemical properties and total heavy metals. (Note: The environmental factors presented in the graphs include total heavy metals and soil physicochemical properties. Warm colors indicate a positive correlation, while cool colors represent a negative correlation. Asterisks denote significance levels: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

According to Fig. 5, both the total concentration of As and its more mobile forms exhibit strong positive correlations with pH and AP. This suggests that increases in pH and AP may promote the accumulation of As. The F1–F3 forms of Zn are strongly positively correlated with TN, which may partly explain the observed overall correlation between Zn and TN. The main form of Cd (F2) is positively correlated with these parameters, while F1 shows a weak negative correlation with pH.

Assessment of potential ecological hazards of heavy metals (Hakanson index method)

Based on Eq. (1), the ecological risk index (Ei) for each heavy metal and the overall risk index (RI) were calculated (Table 2). Based on the ecological hazard index classification in Table 3, the results indicate that As poses a significant ecological threat to the surrounding soil and environment. More than half of the As sampling points fall into the medium to high-risk category. Furthermore, according to the RI results, sites categorized as risk level II or III are primarily driven by the high ecological risk associated with As, further confirming that arsenic is the dominant pollutant in the study area.

Total heavy metals and soil microbial communities

Soil microbial community structure and affinity maps

The top ten bacterial communities at the phylum and genus levels were selected for analysis (Fig. 6). At the phylum level, Proteobacteria was the dominant group, showing a high relative abundance at most sampling sites. This phylum is widely distributed in heavy metal-contaminated soils, arsenic-rich sediments, and both wetland and upland ecosystems, demonstrating strong environmental adaptability. At the genus level, Ralstonia was identified as the dominant genus. As shown in Fig. 7, it belongs to the phylum Proteobacteria. Other notable genera within Proteobacteria include Pseudomonas and MND1. These associations suggest that these genera may share similar responses to heavy metal contamination and environmental conditions.

Correlation between environmental factors and microbial communities

RDA was conducted to investigate the relationships between environmental factors and the top five dominant bacterial phyla (excluding undefined taxa) (Fig. 8a), as well as the top six dominant bacterial genera (Fig. 8b). At the phylum level, these environmental factors collectively explained 80.2% of the variation in soil bacterial communities, with the first and second axes accounting for 69.65% and 5.75% of the variance, respectively. At the genus level, environmental factors explained 73.7% of the variation, with the first two axes explaining 48.98% and 21.24%, respectively.

At the phylum level, Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Chloroflexi exhibited positive correlations with As, while Firmicutes and Acidobacteriota showed negative correlations. This suggests that Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Chloroflexi possess a certain degree of tolerance to As in karst soils. Both Cd and Zn were positively correlated with Cyanobacteria and Acidobacteriota, while negatively correlated with Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Firmicutes. For Pb, a positive correlation was found with Cyanobacteria, whereas negative correlations were observed with Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Firmicutes. At the genus level, microbial taxa positively associated with As included Chloracidobacterium, Geitlerinema_PCC-8501, and MND1. Microbial genera negatively correlated with As included Ralstonia, Pseudomonas, and Bifidobacterium. Notably, genera within Proteobacteria (MND1,Ralstonia and Pseudomonas) exhibited both positive and negative correlations with As, highlighting the complexity of microbial community responses. The overall positive correlation between Proteobacteria and As suggests that most genera within this phylum possess arsenic resistance. Genera positively associated with Cd and Zn included Chloracidobacterium, Geitlerinema_PCC-8501, and MND1, while negatively correlated genera were Ralstonia, Pseudomonas, and Bifidobacterium. For Pb, positively correlated genera were Chloracidobacterium, Geitlerinema_PCC-8501, MND1, and Ralstonia, whereas Pseudomonas and Bifidobacterium showed negative correlations.

An analysis of the relationship between soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities at the phylum level (Fig. 8a) reveals distinct correlation patterns. Soil pH shows a positive correlation with Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Chloroflexi, while exhibiting negative correlations with Firmicutes and Acidobacteriota. AP also has a strong positive correlation with Cyanobacteria and weaker positive correlations with Proteobacteria and Chloroflexi. OM and TN are essential soil nutrients, and their correlations with microbial communities show similar trends. Specifically, OM is positively correlated with Acidobacteriota and Firmicutes, whereas TN is positively correlated only with Acidobacteriota. Both OM and TN exhibit weak correlations with Firmicutes. At the genus level (Fig. 8b), Ralstonia, MND1, Geitlerinema_PCC-8501, and Chloracidobacterium are positively correlated with soil pH, while Pseudomonas and Bifidobacterium show negative correlations. Geitlerinema_PCC-8501 and Chloracidobacterium also exhibit positive correlations with AP. In contrast, OM and TN were negatively correlated for bacteria other than Bifidobacterium, while all other genera are negatively correlated with these two soil properties.

The speciation of heavy metals significantly influences their mobility and toxicity, often posing a greater environmental threat than their total concentrations. Therefore, correlation analyses were conducted between heavy metal speciation and soil microbial communities at both the phylum and genus levels. At the phylum level (Fig. 9a), the correlations between different As species and total As with microbial communities were consistent. Among As species, F4 exhibited the strongest positive correlation with Proteobacteria and Chloroflexi, while F2 showed the highest positive correlation with Cyanobacteria. For Cd, the most strongly correlated species were F1 and F2, and their correlations with microbial communities were similar to that of total Cd. However, the F3 and F4 forms deviate, showing positive correlations with Proteobacteria and negative correlations with Acidobacteriota, in contrast to the trends observed with total Cd. The primary form of Zn (F4) exhibits slightly different correlations with Cyanobacteria compared to total Zn, while the other forms display patterns consistent with the total Zn concentration. For Pb, the main form (F2) shows a negative correlation with Proteobacteria, whereas the other forms exhibit varying degrees of correlation. At the genus level (Fig. 9b), Pseudomonas and Bifidobacterium remain negatively correlated with all major heavy metal forms. The correlations between As forms and microbial communities at the genus level mirror those observed with total As. Similarly, the relationships between the dominant forms of Cd, Zn, and Pb and microbial communities are largely consistent with the patterns seen for their total concentrations.

Presents a heat map of Spearman’s correlation analysis between microorganisms and heavy metal at both the phylum and genus levels. Panels (a) and (b) correspond to the phylum and genus levels, respectively. (Note: Environmental factors include heavy metal speciation. Warm colors indicate positive correlations, while cold colors indicate negative correlations. * denotes P < 0.05.).

Discussion

Results of the migration risk assessment

As pollution is primarily concentrated in lowland areas, forming a gradient of decreasing concentrations from these regions outward (Fig. 2a). The distribution of As concentrations is likely influenced by a combination of soil properties, topographical features, and heavy summer rainfall. The widespread presence of carbonate rocks in karst areas, which contribute to heavy metal enrichment during weathering processes30. The study area is located in a karst depression, where heavy rainfall during summer often leads to soil waterlogging and anoxic conditions. Under such conditions, microbial activity can reduce ferric iron [Fe(III)] to ferrous iron [Fe(II)], resulting in the dissolution of Fe(III) minerals and the subsequent release of adsorbed As into the surrounding aqueous phase31. This dynamic interplay between environmental conditions and microbial processes underscores the potential for enhanced Additionally, acid rain is prevalent in the study area and plays a unique role in regulating arsenic behavior. However, as arsenic concentrations are positively correlated with pH and are more easily released under alkaline conditions, the risk of arsenic leaching due to acid rain is relatively low compared to other heavy metals that are more sensitive to acidic environments32.

As shown in Fig. 2b, Cd is primarily enriched in higher elevation areas; however, its relatively high concentration in lower areas suggests that migration may have occurred. Similarly, Fig. 2c indicates that Pb is concentrated downstream, further supporting the likelihood of contaminant migration. In contrast, Zn is mainly distributed in higher elevation areas (Fig. 2d), has relatively low concentrations, and indicating a lower environmental risk and a distribution pattern likely governed by natural factors. As soil pH decreases, the concentrations of Cd, Pb, and Zn rise due to the replacement or dissolution of adsorbed metal ions by ions such as Na+, H+, and OH− during rainfall. While the risk associated with Zn, Cd, and Pb is lower than that of As, it remains significant and demands attention due to its potential ecological impact.

The Hakanson index identifies As contamination as the most significant source of soil environmental and ecological pollution in the study area. The ecological impact of heavy metals is often reflected in their effects on microorganisms, as microbial communities play a crucial role in soil health and nutrient cycling. Heavy metals primarily affect ecosystems through their influence on microbial communities, which play a critical role in soil health and nutrient cycling. Heavy metals exert dual effects on microorganisms. On one hand, they may trigger stress responses, promoting the development of adaptive defense mechanisms that enable microorganisms to survive and reproduce under harsh environmental conditions33. On the other hand, heavy metals can disrupt normal energy metabolism, thereby inhibiting microbial growth and compromising ecosystem functionality34.

Influence of soil physicochemical properties on total heavy metal concentrations and speciation

The low soil pH in this region is likely associated with acid rain deposition. However, due to the presence of carbonate rocks in karst areas, which possess natural buffering capacity, the leaching of acid rain can be moderated, maintaining soil pH within a neutral to slightly alkaline range35. Honma et al.36demonstrated that As dissolution increases significantly as pH rises. This phenomenon occurs because an increase in pH reduces the number of positive charges and increases the number of negative charges on the soil surface, thereby enhancing the repulsion of arsenate ions37. The adsorption of arsenate anions (H2AsO4− or HAsO42−) decreases, while that of arsenite (H₃AsO₃) increases, resulting in a higher proportion of As in its weakly bound acidic state38,39This pH-driven change enhances the solubility of As, promoting a transition from the more stable F4 form to the highly mobile and bioavailable F1-F3 forms. Consequently, the content of the F4 form decreases, elevating the potential for As mobility and contamination39. While the soil in this study area is in an acidic environment, although it does not enhance As mobility, the risk is still not negligible due to its high F2 form. An decrease in pH can cause Cd to transform from more bioavailable and mobile species into a stable form, thereby reducecing its mobility40. Additionally, lower pH decreases the negative surface charge of active soil constituents, such as iron and manganese oxides or soil minerals, which reduces the adsorption of Pb²⁺. This process may result in elevated proportions of Pb in the F1 and F2 fractions41.

OM plays a significant role in the binding and transformation of heavy metals in soil42. The primary form of OM in soil is humus, which can be further classified into humic acid, fulvic acid, and humin. Among these, humic acid and fulvic acid are the predominant components43. Studies suggest that higher concentrations of humic acid and humin in soil are associated with lower concentrations of certain heavy metals. This relationship indicates that increased organic matter does not always enhance the immobilization of heavy metals44. In this study, the correlation between heavy metals and OM was weak, likely influenced by the specific content of humic acid and humin in the soil. The bioavailable forms of Zn (F1–F3) showed significant correlations with TN, primarily due to nitrogen’s influence on weak acid and organic forms of Zn, particularly the weak acid form45. However, since the dominant form of Zn in the soil is the more stable F4 form, the relationship between total Zn concentration and TN was relatively weak.

The limited availability of adsorption sites on soil surfaces leads to competition between phosphate and arsenate for binding. Phosphate ions, with their strong displacement ability, can effectively displace arsenate from adsorption sites, resulting in arsenate desorption and increased bioavailability46,47. In this study, AP showed a significant positive correlation with the bioavailable forms of As, indicating that AP plays a critical role in influencing As bioavailability.

Influence of unique karst geological conditions on total heavy metal concentrations and forms

The lithology of the study area is primarily limestone. During the weathering and soil-forming processes, it exhibits characteristics of silica depletion and enrichment in iron and manganese, leading to increased concentrations of iron and manganese oxides. These oxides have strong adsorption capacities for heavy metals; therefore, their abundance in the soil can result in elevated heavy metal concentrations48. In such scenarios, the abundant iron and manganese oxides in the soil adsorb As(III). A portion of this adsorbed arsenic is oxidized to As(V) and subsequently released into the solution, while a small amount of As(III) remains bound to the oxide surface. This process mitigates arsenic toxicity by reducing the availability of more toxic arsenic species in the soil49. At most sampling locations, the predominant form of As is F2,. Wang et al.50noted that arsenic behavior in soil is largely influenced by iron-manganese oxides, which can sequester substantial amounts of arsenic. The karst soils of Guangxi, derived from limestone parent material, are particularly rich in these iron and manganese compounds, further influencing the mobility and retention of arsenic in the region51. During the formation of residual soil, elements from the parent material become concentrated, facilitating the development of iron-manganese (Fe-Mn) nodules52. The high concentrations of Fe-Mn oxides in the soils were evaluated in relation to soil texture and the soil-forming matrix. As Fe-Mn oxides dissolve in the soil, the mobility of toxic heavy metals in their reducible states is enhanced during the initial stages of reduction53. Cd predominantly exists in the F2 form, as Fe-O and Mn-O groups effectively adsorb Cd through complexation reactions54. This interaction highlights the significant role of Fe-Mn oxides in regulating the mobility and bioavailability of heavy metals in soils derived from limestone and Permian parent materials.

Correlation analysis between soil microbiota and heavy metal concentrations

Phylum-level analysis

Among As-resistant microorganisms, Proteobacteria exhibit the highest resilience. In As-contaminated soils, the availability of essential nutrients for Proteobacteriais significantly reduced. To survive in such environments, these microorganisms adjust their metabolic activities through diverse pathways to acquire necessary carbon sources and nutrients55,56. Proteobacteria exhibited the strongest correlation with the F4 fraction of As, suggesting that its presence may facilitate the transformation of As into a more stable residual form, thereby reducing its environmental risk and mobility. Cyanobacteriadisplay resistance not only to As but also to Cd, Pb and Zn, attributed to their high adsorption capacity for heavy metals. These organisms can utilize heavy metals as nutrient sources, but their subsequent decomposition releases As, Cd, Pb, and Zn back into the environment, thereby contributing to increased total heavy metal concentrations57.While most studies report a positive correlation between Firmicutesand heavy metal pollution58,59, as these microorganisms can acquire genetic traits that enhance environmental adaptability60. the findings of this study indicate otherwise. The Firmicutes community in the study area appears to be intolerant to As, Cd, Pb, and Zn. This may be attributed to the low available phosphorus content in the soil, which contributes to a negative correlation between Firmicutesand heavy metal concentrations61.

Genus-level analysis

Regarding As, the primary contaminant in the study area, MND1 demonstrates significant resistance. This ability is linked to specific β-proteobacteria within MND1, which possess arsenic metabolism and detoxification functions. These functions are facilitated by the aioA gene, which encodes the large subunit AioA of arsenite oxidase. The presence of a gene analogous to aioA in MND1allows it to adapt and persist in environments with high As concentrations62. In environments with higher Pb levels, the growth of Ralstonia strains, such as Ralstonia Bcul-1, has been shown to enhance Pb adsorption as a nutrient from the soil63 However, Ralstonia displayed weak resistance to Pb in this study, likely due to the relatively low Pb concentrations in the area. Furthermore, Ralstonia demonstrates adaptability to Cd, with the toxic Cd2+ ion serving as a nutrient that the genus can effectively adsorb. Under Cd2+ stress, Ralstonia produces specific cell wall components that not only enhance its tolerance but also increase its Cd2+adsorption capacity64, contributing to its abundance in Cd-contaminated environments.

Studies have shown that in arsenic-contaminated soils, Ralstonia eutropha Q2-8 reduces the concentration of bioavailable arsenic and increases the concentration of stable arsenic forms by upregulating the expression of the arsMgene65. However, findings from this study suggest that Ralstonia lacks significant resistance to Cd and As, implying that resistant strains within this genus are either absent or rare. Research by Satyapal et al.66 highlighted Pseudomonasfrom the mid-Ganges plain in Bihar, India, as a promising candidate for As remediation due to its As resistance mechanisms. These mechanisms are often associated with plasmid-borne genes, suggesting the plasmid-based gene system is a critical factor in As tolerance67. However, in this study, Pseudomonas was identified as non-resistant to arsenic, indicating the absence of functional As resistance mechanisms in the strains observed.

Soil physicochemical properties and microbial community analysis

Soil pH exhibits a strong positive correlation with microbial communities at both the phylum and genus levels. Xu et al.68 also found a positive correlation between Proteobacteria and pH, which is consistent with the findings of this study. In this study, Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria demonstrated a negative correlation with OM and TN. This may be attributed to the ability of Proteobacteriato utilize various recalcitrant carbon sources under nutrient-deficient conditions69. while Cyanobacteriaare known to produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), which facilitate aggregation with soil particles and help them withstand harsh environmental conditions70. Additionally, Chloroflexishowed a negative correlation with TN, which may be attributed to its dependence on organic matter as an energy source for metabolic activities71. In contrast, Firmicutes exhibited a positive correlation with OM, suggesting that an increase in Firmicutescan enhance soil nutrient availability72. These findings underscore the intricate relationships between soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities, shaping nutrient cycling and soil health.

Potential for microbial remediation in karst areas

Proteobacteria exhibit a positive correlation with both pH an As concentrations, indicating their ability to survive in soils with high pH and severe As contamination. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Yang et al.73. The ability of Proteobacteria to tolerate As pollution and adapt to low nutrient availability likely stems from their capacity to utilize diverse carbon sources. The increase in Proteobacteria contributes to the reduction of arsenic mobility and toxicity, primarily because most Proteobacteria carry the arsMgene, which facilitates arsenic methylation. This methylation process reduces arsenic’s mobility and toxicity in soil74,75. This mechanism may also explain the high survival rate of Proteobacteria observed in this study. Previous research has demonstrated the role of Proteobacteria in promoting the reduction of heavy metals. Research by Emenike et al.76 highlights the role of Proteobacteria in accelerating the bioreduction of heavy metals, including As, Cu, and Zn, positioning them as effective agents for bioremediation in contaminated environments. In addition, Proteobacteria’s low nutrient requirements make them well-suited for remediating As-contaminated, nutrient-deficient soils. In contrast, Firmicutes display a negative correlation with all heavy metals and only a positive correlation with OM. The heavily polluted and nutrient-poor conditions in the study area appear unfavorable for the growth of Firmicutes. Firmicutes may serve as a potential microbial indicator for evaluating the effectiveness of heavy metal remediation in karst soils.

Conclusions

This study investigated heavy metal contamination in the soil of a karst depression in Guangxi to identify the pollution levels and migration characteristics of heavy metals in karst regions. The results revealed severe As-contamination, particularly in low-lying areas in the northeastern part of the study region. As was primarily present in the highly mobile F2 (reducible fraction), which is mainly influenced by soil pH and AP. Moreover, the unique karst depression topography and frequent summer rainfall in the region lead to waterlogging and anoxic conditions, resulting in significant As release into the soil solution. The study also found that Proteobacteria species could survive in alkaline, nutrient-deficient, and heavily As-contaminated soils. This suggests that Proteobacteria may be used alone or in combination with other effective arsenic-degrading materials as a green and viable strategy for arsenic remediation. Interestingly, a negative correlation was observed between Firmicutes and As- concentration, differing from most existing studies. This finding indicates that Firmicutes may serve as a potential bioindicator for evaluating arsenic pollution control effectiveness. Preventing further arsenic contamination is essential for protecting the surrounding ecosystem. The insights into microbial community distribution in contaminated soils provide a theoretical basis for microbial arsenic remediation in this type of karst soil.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, G., Du, R. Y. & Wang, X. Genetic regulation mechanism of cadmium accumulation and its utilization in rice breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021247 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Lead toxicity: health hazards, influence on food chain, and sustainable remediation approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072179 (2020).

Natasha, N. et al. Zinc in soil-plant-human system: A data-analysis review. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152024 (2022).

Huo, A. D. et al. Risk assessment of heavy metal pollution in farmland soils at the Northern foot of the Qinling mountains, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214962 (2022).

Gong, C. et al. Spatial distribution characteristics of heavy metal(loid)s health risk in soil at scale on town level. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20867-4 (2022).

Zhang, L. X., Zhu, G. Y., Ge, X., Xu, G. & Guan, Y. T. Novel insights into heavy metal pollution of farmland based on reactive heavy metals (RHMs): pollution characteristics, predictive models, and quantitative source apportionment. J. Hazard. Mater. 360, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.075 (2018).

Chi, G., Qin, F., Zhu, B. & Chen, X. Long-term wetland reclamation affects the accumulation and profile distribution of heavy metals in soils. J. Soil. Sediment. 23, 1706–1717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-022-03422-6 (2023).

Xiao, L., Guan, D. S., Peart, M. R., Chen, Y. J. & Li, Q. Q. The respective effects of soil heavy metal fractions by sequential extraction procedure and soil properties on the accumulation of heavy metals in rice grains and brassicas. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 24, 2558–2571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-8028-8 (2017).

Wang, L. C., Lee, D. W., Zuo, P., Zhou, Y. K. & Xu, Y. P. Karst environment and Eco-Poverty in Southwestern China: A case study of Guizhou Province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 14, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-004-0004-4 (2004).

Ren, J. et al. Research on the distribution characteristics and enrichment mechanisms of heavy metal pollution in areas with high geochemical background. Res. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.13198/j.issn.1001-6929.2024.08.25 (2024).

Abdu, N., Abdullahi, A. A. & Abdulkadir, A. Heavy metals and soil microbes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 15, 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-016-0587-x (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Assessment of the pollution of soil heavy Metal(loid)s and its relation with soil microorganisms in wetland soils. 14, 12164 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Accumulation of heavy metals in rice and the microbial response in a contaminated paddy field. J. Soil. Sediment. 24, 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-023-03643-3 (2024).

Chun, S. J., Kim, Y. J., Cui, Y. & Nam, K. H. Ecological network analysis reveals distinctive microbial modules associated with heavy metal contamination of abandoned mine soils in Korea. Environ. Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117851 (2021).

Ma, B. J. et al. The pollution status and research progress of remediation for arsenic factory sites in China. Min. Metall. 32, 125–131 (2023).

Qin, X. Soil quality status and repair study of contaminated site in a legacy arsenic plant in Hechi,Guangxi Master’s dissertation thesis, Guangxi University (2018).

Protection, C. M. & o., E. Soil and sediment-Determination of aqua regia extracts of 12 metalelements-Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. (HJ 803–,Putting Into Effect As of AUG.1,2016) (in Chinese), (2016). https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/jcffbz/201606/W020160701531772799289.pdf (2016).

Protection, C. M. & o., E. Soil and sediment-Sequential extraction procedure of speciation of 13 trace elements. (GB/T25282-2010,Putting Into Effect As of Nov.10,2010) (in Chinese) (2010).

Protection, C. M. E. Soil-Determination ofpH- Potentiometry. (HJ 962–2018,Putting Into Effect As of Jul.29,2018) (in Chinese) (2018).

China., A. I. S. o. t. P. s. R. o. Soil testing Part 7:Method for determination of available phosphorus in soil. (NY/T 1121.7–2014,Putting Into Effect As of Oct.17,2014) (in Chinese) (2014).

China., A. I. S. o. t. P. s. R. o. Soil testing Part 24:Determination of total nitrogen in soil Automatic kjeldahl apparatus method. (NY/T 1121.24–,Putting Into Effect As of Jun.6,2012)(in Chinese) (2012). (2012).

China., A. I. S. o. t. P. s. R. o. Soil Testing Part 6: Method for determination of soil organic matter. (NY/T 1121.6–2006,Putting Into Effect As of Jul.10,2006) (in Chinese) (2006).

Magoc, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 (2011).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods. 10 (11), 57–U. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nmeth.2276 (2013).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2584 (2016).

Haas, B. J. et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 21, 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.112730.110 (2011).

Lin, Q. M., Huang, Z. L. & Fan, R. H. Geochemical characteristics of soil in Jinchengjiang District of Hechi City,Guangxi Mineral Resources and Geology 35, 1141–1146, (2021). https://doi.org/10.19856/j.cnki.issn.1001-5663.2021.06.016

Hu, B. et al. Fraction distribution and bioavailability of soil heavy metals under different planting patterns in Mangrove restoration wetlands in Jinjiang, Fujian, China. Ecol. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106242 (2021).

Zhang, G. L. et al. Heavy metal fractions and ecological risk assessment in sediments from urban, rural and reclamation-affected rivers of the Pearl River Estuary, China. Chemosphere 184, 278–288, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.155

Ma, Y. et al. Distribution characteristics, risk assessment, and source analysis of heavy metals in farmland soil of a karst area in Southwest China. Land 13, 979 (2024).

Han, Y. S., Park, J. H., Kim, S. J., Jeong, H. Y. & Ahn, J. S. Redox transformation of soil minerals and arsenic in arsenic-contaminated soil under cycling redox conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.120745 (2019).

Li, W., Deng, Y., Wang, H., Hu, Y. & Cheng, H. Potential risk, leaching behavior and mechanism of heavy metals from mine tailings under acid rain. Chemosphere 350, 140995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140995 (2024).

Prabhakaran, P., Ashraf, M. A. & Aqma, W. S. Microbial stress response to heavy metals in the environment. RSC Adv. 6, 109862–109877. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra10966g (2016).

Li, H., Yao, J., Min, N. & Duran, R. Comprehensive assessment of environmental and health risks of metal(loid) s pollution from non-ferrous metal mining and smelting activities. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134049 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Inputs and transport of acid mine drainage-derived heavy metals in karst areas of Southwestern China. Environ. Pollut. 343, 123243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.123243 (2024).

Honma, T. et al. Optimal soil Eh, pH, and water management for simultaneously minimizing arsenic and cadmium concentrations in rice grains. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 4178–4185. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05424 (2016).

Jiang, J. et al. Evaluation of ferrolysis in arsenate adsorption on the paddy soil derived from an oxisol. Chemosphere 179, 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.115 (2017).

A., L. H., L., M. C., Z., J. Q., H., L. & C., Z. L. Sources of arsenic in soil and affecting factors of migration and release: A review. Soils 52, 234–246. https://doi.org/10.13758/j.cnki.tr.2020.02.003 (2020).

Chen, B. B. The study on the migration and transformation of arsenic in soil Master’s dissertation thesis, East China Normal University (2015).

Meng, K. et al. Interaction and transport characteristics of lead and cadmium indifferent Soil-wheat systems. Environ. Sci. 44, 6319–6327. https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.202211265 (2023).

Qiao, P. et al. Process, influencing factors, and simulation of the lateral transport of heavy metals in surface runoff in a mining area driven by rainfall: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159119 (2023).

Kwiatkowska-Malina, J. Functions of organic matter in polluted soils: the effect of organic amendments on phytoavailability of heavy metals. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 123, 542–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.06.021 (2018).

Deng, Y. X., Weng, L. P. & Zhu, G. F. A review on the Lnfluence of humic substance on the speciation distribution and transformation of arsenic in soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.19672/j.cnki.1003-6504.0892.22.338 (2023).

Liao, B. X., Shen, W. L. & He, Y. Distribution characteristics and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in typical soil profiles of Muchuan County, Sichuan Province. Rock. Mineral. Anal. 42, 1203–1219. https://doi.org/10.15898/j.ykcs.202305090062 (2023). https://link.cnki.net/doi/

He, Z. J., Hua, L. & Hong, C. Q. Effects of interaction between nitrogen and zinc on forms of zinc in Yellow - Brown soil. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 209–212 (2004).

Zhang, M. et al. Effects of exogenous phosphates on speciation and bioavailability of arsenic and cadmium in farmland soils. J. Soils Sediments. 23, 1832–1843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-023-03448-4 (2023).

Zhang, J. X. et al. Effect of phosphate on monothiosarsenate adsorption to soil. China Environ. Sci. 42, 3849–3857. https://doi.org/10.19674/j.cnki.issn1000-6923.2022.0153 (2022).

Chen, B., Lu, B. K. & Qiu, W. Source and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in soil in karst landforms of Guangxi. Environ. Pollution Control. 44, 639–644. https://doi.org/10.15985/j.cnki.1001-3865.2022.05.015 (2022).

Rady, O. et al. Adsorption and catalytic oxidation of arsenite on Fe-Mn nodules in the presence of oxygen. Chemosphere https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127503 (2020).

Wang, H. T. et al. Bioavailability and risk assessment of arsenic in surface sediments of the Yangtze river estuary. Mar. Pollut Bull. 113, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.076 (2016).

Feng, Y. F. et al. Geochemical characteristics of heavy metal enrichment in soil Fe-Mn nodulesin the karst area of Guangxi. Geol. J. China Universities. 28, 787–798. https://doi.org/10.16108/j.issn1006-7493.2021079 (2022).

Ji, W. B. et al. Formation mechanisms of iron-manganese nodules in soils from high geologicabackground area of central Guangxi. Chin. J. Ecol. 40, 2302–2314. https://doi.org/10.13292/j.1000-4890.202108.006 (2021).

Contin, M., Mondini, C., Leita, L. & De Nobili, M. Enhanced soil toxic metal fixation in iron (hydr)oxides by redox cycles. Geoderma 140, 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2007.03.017 (2007).

Yang, T. et al. Removal mechanisms of cd from water and soil using Fe–Mn oxides modified Biochar. Environ. Res. 212, 113406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113406 (2022).

Tseng, S. C., Liang, C. M., Chia, T. & Ton, S. S. Changes in the composition of the soil bacterial community in heavy Metal-Contaminated farmland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168661 (2021).

Kou, B. et al. The relationships between heavy metals and bacterial communities in a coal gangue site. Environ. Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121136 (2023).

Ni, L. X. et al. Effects of cyanobacteria decomposition on the remobilization and ecological risk of heavy metals in Taihu lake. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26, 35860–35870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06649-y (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Effects of heavy metals on bacterial community surrounding Bijiashan mining area located in Northwest China. Open. Life Sci. 17, 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1515/biol-2022-0008 (2022).

Xiao, W. W., Lin, G. B., He, X. M., Yang, Z. G. & Wang, L. Interactions among heavy metal bioaccessibility, soil properties and microbial community in phyto-remediated soils nearby an abandoned Realgar mine. Chemosphere https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131638 (2022).

Jacquiod, S. et al. Long-term industrial metal contamination unexpectedly shaped diversity and activity response of sediment Microbiome. J. Hazard. Mater. 344, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.09.046 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Arsenic pollution from human activities drives changes in soil microbial community characteristics. Environ. Microbiol. 25, 2592–2603. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.16442 (2023).

Kudo, H. et al. Bayesian network highlights the contributing factors for efficient arsenic phytoextraction byin a contaminated field. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165654 (2023).

Huang, Q., Ye, J., Li, Y. C., Liu, Q. W. & Wang, Y. X. Removal efficiency and mechanism of heavy metal lead (Pb) by Ralstonia Beul-1 in soil. J. Subtropical Resour. Environ. 17, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.19687/j.cnki.1673-7105.2022.01.004 (2022).

Huang, J. Q., Liu, C. W., Price, G. W., Li, Y. C. & Wang, Y. X. Identification of a novel heavy metal resistant Ralstonia strain and its growth response to cadmium exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125942 (2021).

Rahman, M. A. & Hassler, C. Is arsenic biotransformation a detoxification mechanism for microorganisms? Aquat. Toxicol. 146, 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.11.009 (2014).

Satyapal, G. K. et al. Possible bioremediation of arsenic toxicity by isolating Indigenous bacteria from the middle gangetic plain of Bihar, India. Biotechnol. Rep. 17, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2018.02.002 (2018).

Das, S. K. Influence of phosphorus and organic matter on microbial transformation of arsenic. Environ. Technol. Innov. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.100930 (2020).

Xu, D. et al. Effects of compost as a soil amendment on bacterial community diversity in saline–alkali soil. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1253415 (2023).

Bian, F. et al. Intercropping improves heavy metal phytoremediation efficiency through changing properties of rhizosphere soil in bamboo plantation. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125898 (2021).

Sepehr, A., Hassanzadeh, M. & Rodriguez-Caballero, E. The protective role of cyanobacteria on soil stability in two aridisols in Northeastern Iran. Geoderma Reg. 16, e00201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2018.e00201 (2019).

Sui, X. R., Wang, Y., Liu, Y. G., Zhang, Y. J. & Wu, L. F. Responses of soil nutrients and microbial community to altitude in typical pinusyunnanensis forest at Rocky desertification region. Acta Agriculturae Zhejiangensis. 33, 2348–2357 (2021). https://link.cnki.net/urlid/33.1151.s.20211129.1612.044

Zhang, G. L. et al. The response of soil nutrients and microbial community structures in Long-Term tea plantations and diverse agroforestry intercropping systems. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147799 (2021).

Yang, R. Q. et al. Effects of different heavy metal pollution levels on microbial community structure and risk assessment in Zn-Pb mining soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 52749–52761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26074-6 (2023).

Liu, J., Pei, R., Liu, R., Jing, C. & Liu, W. Arsenic methylation and microbial communities in paddy soils under alternating anoxic and oxic conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 148, 468–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.10.030 (2025).

Liu, J., Ye, L. & Jing, C. Active microbial arsenic methylation in saline-alkaline paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 865, 161077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161077 (2023).

Emenike, C. U., Agamuthu, P., Fauziah, S. H., Omo-Okoro, P. N. & Jayanthi, B. Enhanced bioremediation of Metal-Contaminated soil by consortia of Proteobacteria. Water Air Soil. Poll. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-023-06729-3 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Guangxi Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. Guike AB23075157 and AB21196037), Open project of the Technical Innovation Center of Mine Geological Environmental Restoration Engineering in Southern Karst Area, Ministry of Natural Resources (NFSS2023016) and Science and Technology Program of Nanning City (RC20220104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.J. Writing-original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation. Z.J. Writing-review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. Z.Y.Y. Investigation, Validation, Visualization. H.H. Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Resources. M.Y.Q. Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization. L.D.J. Resources, Methodology. W.S.F. Writing-review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. X.T. Writing-review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology. C.F.N. Resources, Funding acquisition. H.H.X. Resources, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, H., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y. et al. Heavy metal pollution migration and its ecological impact on microbial communities in the karst region of Guangxi. Sci Rep 15, 14750 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98809-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98809-z