Abstract

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have been one of the most strongly impacted regions by the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emergency, with more than 83 million reported infections and 1.7 million deaths until December 2023, intensifying economic and social inequalities. This study aimed to provide information to the regional SARS-CoV-2 surveillance programs by determining genomic, socio-environmental, and sequencing capacity patterns associated with the circulation of the virus in Latin America up to 2023. Data from 24 countries in LAC were analyzed using public databases up to December 2023. A sampling of SARS-CoV-2 sequences from cases in the region enabled a phylogenomic study to elucidate the temporal distribution of various variants of concern (VOCs), mutations, and recombinants. Also, we identified differences in sequencing capabilities in LAC. Additionally, correlation and generalized linear model (GLM) analyses were conducted to explore potential associations between 89 socio-environmental variables and five COVID-19 indicators at the country level. The phylogenomic analyses revealed a diversity of variants with the predominance of some during specific periods, mainly VOCs and some recombinant cases, and a mutation rate of 8.39 × 10–4 substitutions per site per year, which are in line with other regions of the world. Besides, a low sequencing rate in LAC (on average 0.7% of cases) and incomplete databases in several countries were identified. In the analysis of indicators, correlations between 9 socio-environmental indicators and four COVID-19 variables associated with cases, deaths, and diagnostic tests related to the virus in the region, although not for sequencing percentages. This study provides information about the development of COVID-19 disease in LAC in terms of the viral genome, sequencing capabilities, and the region’s complex socio-environmental conditions. Therefore, emphasis must be placed on implementing an integrated epidemiological surveillance approach to strengthen public health infrastructure and improve cooperation and preparedness for future infections affecting this region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the causal agent of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a highly contagious infectious disease with a diversity of clinical presentations1 and that impacted the world as a pandemic2,3,4. By the end of December 2023, more than 773 million cases and at least 7 million deaths were reported worldwide (https://data.who.int/ dashboards/covid19/data ).

SARS-CoV-2 is part of the Coronaviridae family, enveloped and positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses5. Its genomic sequence has been shown to share 80% sequence identity with SARS-CoV and 50% with MERS-CoV, coronaviruses previously associated with outbreaks5. The WHO has designated multiple variants based on their evaluated potential to expand and replace previous variants, for causing new waves of infection with greater circulation and for the need for adjustments in public health actions, highlighting variants of concern (VOC, such as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and the original Omicron lineage), variants of interest (VOI) and variants under monitoring (VUM).

Hundreds of studies have provided insights regarding the pandemic’s biology, clinical outcome, and social impact. Even though the emergency was officially over in May 20236, we have witnessed many outbreaks in several regions. This behavior is due to the emergence of mutant variants of SARS-CoV-2 as part of the genetic evolution and adaptation, in which new genome versions are generated7.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), extending beyond public health, where the spread of the virus presents different patterns between countries, which could be attributed to variations in health infrastructure and economic strength, as well as by the prevention measures adopted by each country during the pandemic8. Additionally, the ecological and social diversity present in Latin America is one of the causes of the presence of a wide variety of genotypes at the local level since it allows SARS-CoV-2 to spread and evolve in the region8,9,10. These factors have made Latin America one of the most strongly impacted regions, with more than 83 million reported infections and 1.7 million deaths until December 2023 (https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/data). The milestones of the development of the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America are shown in (Fig. 1).

Brazil became the first country in Latin America to confirm a case of COVID-19 on February 26, 2020, associated with a man who had traveled to Italy, where a significant outbreak had been recorded. Subsequently, Argentina reported the first death in the region on March 7 of the same year. The arrival of the pandemic in Latin America was accompanied by limitations in pandemic prevention and control measures due to the living conditions and public health limitations present in low- and middle-income countries11. This region experienced the highest infection rate in proportion to the population, corresponding to 17% of cases worldwide, a figure comparable to that of India, despite having a population almost one billion smaller12. Furthermore, many Latin American countries, especially those with low income, faced limitations in conducting genomic surveillance compared to developed countries12. A study conducted in the region demonstrated that the variants associated with multiple reintroductions and their mutation frequencies align with global trends, representing one of the first integrated analyses in the region13.

Considering the situation mentioned above, the CABANAnet initiative (Capacity building for Bioinformatics in Latin America, https://cabana.network/) has supported the development of a regional project entitled "Genomic, socio-environmental, and capability patterns regarding the circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in Latin America until the year 2024 to support epidemiological surveillance using a multivariate approach". In this project, it was considered crucial to update the data from the last four years of the pandemic (2020 – 2023), which include not only genomic surveillance in Latin America and the Caribbean but also establishing possible relationships between COVID-19 parameters and country-level indicators (social, economic, environmental, and demographic; from now on "Socio-environmental"), as well as to assess sequencing capabilities. Consequently, this study aimed to determine genomic, socio-environmental, and sequencing capacity patterns associated with the circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in Latin America until 2024 to support epidemiological surveillance at the regional level.

Material and methods

The study used data from 24 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela). The data correspond to samples and information available in databases until December 31, 2023. For the general data (Table 1), parameters of demographics and COVID-19 indicators (cases and deaths) were retrieved from Worldometers platform (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/), while sequencing data was obtained from GISAID database (https://gisaid.org/). From GISAID data, Recombinant lineages were identified based on the lineage ID (Pango) and the annotation found in “Pango-Designation” available at: https://github.com/cov-lineages/pango-designation/blob/master/lineage_notes.txt. See below for details of other databases used in specific analyses. The general pipeline is presented in Fig. 2.

Analysis of circulating genotypes of SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 sequences and metadata from 24 countries were retrieved from the GISAID database (https://gisaid.org/), encompassing a total of 3 066 sequences based on a globally subsampled SARS-CoV-2 dataset from Nextstrain (https://nextstrain.org/ncov/gisaid/global/all-time?dmax=2023-12-31). All metadata from these records are available as Supplementary material. Utilizing the GISAID platform, the most prevalent variants were analyzed to study the divergence process of SARS-CoV-2 in the region. The analysis involved constructing a tree to elucidate the divergence process in relation to the accumulation of mutations. Additionally, the most prevalent variants and their metadata were cataloged by country, providing a visualization of the diversity and frequency of each variant.

Phylogenomic analysis

Phylogenomic analysis was performed using the 3 066 sequences. Mafft v7.50814 was employed to align all sequences. Construction of the phylogenetic tree was done using IQ-tree v2.1.215, including ModelFinder to select the best nucleotide substitution model (using the Bayesian Information Criterion BIC, the best model was GTR + F + R2). The phylogenomic tree was visualized with iTOL v.416, incorporating data of year and variant, as reported in14. Analyses were performed using the High-Performance Computing Cluster of the Center for Research in Materials Science and Engineering (CICIMA-HPC), University of Costa Rica.

Analysis of demographic, social, economic, environmental and SARS-CoV-2 indicators

A total of 155 demographic, social, economic, and SARS-CoV-2 indicators from the 24 countries were retrieved from several public databases (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/, https://data.unicef.org/resources/resource-type/datasets/, https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/documentation-and-downloads, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/average-iq-by-country, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.PRCP.MM?most_recent_value_desc=true, https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/temperature, https://countryeconomy.com/gdp, https://gisaid.org/). The indicators were assessed and selected based on their availability among all nations; otherwise, they were excluded from the subsequent statistical analysis. Following this data selection and completeness assessment, 89 socio-environmental and the five COVID-19 indicators (cases per 1 million people, deaths per 1 million people, deaths per 1 million COVID-19 cases, tests per 1 million people, and percentage of sequenced genomes) were selected for subsequent statistical analyses. The whole dataset of 155 and the 94 selected indicators by country is included as Supplementary Material. Using R software (https://www.r-project.org/) and the ‘corrplot’ package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/), a Pearson correlation between all socio-environmental indicators versus SARS-CoV-2 indicators was computed using the program’s 'corrplot.mixed’ function, based on values for all the 24 countries. Subsequently, indicators with a Pearson correlation coefficient of > 0.3 were selected after visualization and analysis with the ‘psych’ package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html). After assumption validation, generalized linear models (GLM) were implemented to study the association between demographic, social, and economic indicators as possible predictors of SARS-CoV-2 parameters (normalized values for infections, deaths, and sequencing) using the ‘glm’ function in the R software. Predictors with a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant in each model.

Results

The analysis of COVID-19 cases from LAC countries (Table 1) shows that Brazil had the highest absolute values for cases and deaths and in the number of SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences. Nicaragua had the lowest number of reports for COVID-19 cases and deaths, while Cuba had the lowest number of SARS-CoV-2 sequences. When the data from each country are adjusted by population, the results tend to differ. Uruguay and Chile reached the highest rates of 297,799 and 276,925 COVID-19 cases per million inhabitants, respectively. Peru stands out with 6 595 deaths per million inhabitants and 48 823 deaths per million cases, which correspond to the highest rates associated with deaths attributed to COVID-19 in the region. Chile and Uruguay again stand out in tests performed per million population, with 2 605 252 and 1 749 083 tests per million population, respectively. According to the data obtained from official reports, Nicaragua has the highest number of SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences per case in the region. On the other hand, countries such as Haiti and Nicaragua reported the lowest rates of cases, deaths, and COVID-19 tests per million people, while Bolivia and Cuba had the lowest percentages of sequencing per COVID-19 cases (Table 1).

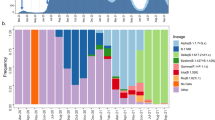

On the other hand, a phylogenomic analysis was performed with the sub-sampled sequences. The phylogenomic tree (Fig. 3) shows that during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America and the Caribbean, a diversity was observed in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Alpha, Delta, and Gamma (VOCs), as well as other non-VOCs. By 2022, the Omicron VOC became predominant, and in 2023, the Omicron and its sub-lineages were mainly present. This information is further complemented by the distribution and predominance of specific VOCs across the countries in the region (Fig. 4a), as well as by the SARS-CoV-2 mutation rate in the region, which is estimated at 8.39 × 10–4 substitutions per site per year (Fig. 4b).

Landscape of the SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating in Latin America and the Caribbean until December 2023. (A). Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Pie charts indicate the relative abundance of distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants in each country. (B). Mutation rate of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes during the pandemic, including different variants (colors) and the model (black line).

Regarding the analysis of the metadata of the COVID-19 sequences, it was observed that five of the total parameters exhibited several degrees of completeness. For example, “location” was reported with a completeness value as low as 40.5% (Table 2), indicating a loss of specific information about the sample’s origin. The “sex” parameter was represented in five categories: four due to differences in language and one due to a typographical error. Furthermore, three of these parameters lacked uniformity in metadata representation, with the same information being presented in two or more distinct formats.

Finally, 89 socio-environmental indicators and five COVID-19 indicators were initially collected. Details are presented in the Supplementary Material. As shown in Table 3, four COVID-19 parameters (COVID-19 cases per million population, COVID-19 deaths per million population, COVID-19 deaths per million COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 tests per million population) presented strong correlations (positive or negative) and statistically significant association with at least one socio-environmental indicator. In contrast, the percentage of SARS-CoV-2 sequencing did not show a statistically significant correlation or association with any of the indicators under investigation.

Discussion

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is one of the regions most affected by the COVID-19 emergency, with 1.8 million cumulative deaths by the end of 2023, followed by Europe, which reported 2.3 million deaths (https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=c). LAC, home to eight of the 20 most unequal countries in the world, where three-quarters of the nations are classified as low or lower-middle income15, experienced a significant disparity in COVID-19 deaths, ranging from 74 to 6,595 deaths per million inhabitants. Additionally, the pandemic has intensified economic and social inequalities, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations and highlighting the need for integrated strategies to strengthen health systems and improve resilience to future crises16. Social containment measures to reduce the spread of the virus had varying devastating impacts, exacerbating the vulnerability of informal workers and limiting their access to social protection. This inequality mainly affected the elderly and disadvantaged populations17, with an increased digital gap and limited access to education and essential services15, revealing a lack of preparedness for addressing the crisis18.

In this study, data from 24 countries in LAC were analyzed using public databases as the primary source of information. A sampling of SARS-CoV-2 sequences from cases in the region enabled the phylogenomic study to elucidate the temporal distribution of various VOCs, mutations, recombinants, and more. Additionally, correlation and association analyses were performed using GLM between socio-environmental and SARS-CoV-2 indicators, with data from each country included in the study.

Patterns of sequencing capability and genomic surveillance

Genomic surveillance, comprised of epidemiological analysis, high-throughput molecular technologies, and bioinformatics, has proven to be an essential tool for monitoring and managing infectious diseases. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, this surveillance has been crucial for tracking the evolution, lineage diversity, and global spread of the virus, as well as optimizing molecular tests, treatments, and vaccines to guide public health responses globally14,19,20,21. However, global SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance has shown imbalances influenced by socioeconomic factors, available surveillance, and laboratory capacity before the pandemic19. Europe and the Americas have led contributions of SARS-CoV-2 sequences to public repositories, mainly from high-income countries, which presented a proportion of confirmed cases 16 times higher than low- and middle-income countries22.

Regarding sequencing, it has been proposed that at least 5% of SARS-CoV-2 positive samples should be sequenced to detect viral lineages with a prevalence of 0.1 to 1.0%23. Regional reports indicate that this value has yet to be achieved in any country in LAC. In the present study, by the end of 2023, the sequencing percentage of total cases in LAC was 0.7%, surpassing the previously reported 0.4% in the region as of December 202113. Only four countries (Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Nicaragua) sequenced more than 2% of confirmed cases, with Nicaragua being the only country with a sequencing rate above 5%. However, these numbers should be taken with caution, as the cases per million inhabitants in these countries correspond to the lowest rates in the region, which the underreporting of cases could explain. Thus, these data may not reflect the true extent of the disease, as was particularly observed in Nicaragua due to the minimization of the pandemic24. As indicated in our previous study, the data for most countries with high sequencing percentages are biased due to the small number of reported cases adjusted for population13.

Regarding metadata associated with sequences, variability was observed in the completeness and uniformity of data in the GISAID database, particularly in location parameters (40.5% completeness, i.e., 59.5% missing data) and gender (5 categories, non-uniform). This deficiency in data availability has been previously documented, with approximately 63% of sequences lacking demographic data, such as age and gender, being more frequent in high-income regions22. The United States and the United Kingdom are examples of this, as although they have uploaded many sequences, there is a high percentage of missing metadata for age and gender25. In contrast, Slovakia and Slovenia have provided limited sequences with high metadata completeness25. As noted in previous studies, the lack of metadata limits the proper interpretation of results26. Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of providing more complete metadata to maximize its utility in epidemiological analyses.

Phylogenomic patterns in the LAC region

Phylogenomic analyses were run with a subsample of 3 066 sequences until 2023. In the first period during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic in LAC, a diversity was observed in the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants, including VOCs such as Alpha, Delta, and Gamma, as well as variants not classified as VOCs, in line with previous regional reports13,27. The Gamma variant is the only VOC initially identified in LAC, specifically in Brazil28. Colombia and Venezuela played a significant role in its spread29. This variant stood out for its high transmissibility and prevalence in the region during the first half of 2021.

Other lineages, including the VOI Mu and Lambda were first reported in Colombia and Peru, respectively30, as well as unique lineages in Costa Rica and Central America14,31. In the case of Mu, the lineage outcompeted all other variants in Colombia, including the Gamma VOC, in May 202132. A similar pattern was found for Lambda in Peru during the period from March to June 202113.

Later, the Delta variant emerged as the dominant variant in the second half of the same year, possibly associated with border openings and its crucial role in lineage dispersal29, unlike the first half of 2021, where lineage dominance was more specific to each country13.

By 2022, the Omicron variant had become dominant, and in 2023, Omicron sub-lineages prevailed, consistent with the global dynamics of this variant’s spread28. This dynamic included reports of many sequences with more mutations and recombinant genomes, a phenomenon associated with the co-circulation of variants in the region, which highlights the complexity of virus transmission and evolution19,22, not only due to co-infections that promote recombination33,34 but also sustained increases in mutation rates. In the latter case, according to our analysis, the substitution rate estimated (8.39 × 10−4 substitutions per site per year) is similar to the reported in the literature in the range of 8–20 × 10−4 substitutions per site per year worldwide13,35,36,37.

Patterns between socio-environmental factors and COVID-19 development in LAC

A correlation and GLM association analysis were conducted using socio-environmental and SARS-CoV-2 indicators, totaling 94 parameters. Of the diverse socio-environmental indicators analyzed in this study, 9% (8/89) simultaneously showed a Pearson correlation above the threshold investigated and were statistically significant through GLM analysis with COVID-19 indicators. Temperature was the only environmental predictor associated with two COVID-19 indicators (cases and tests performed, each adjusted per million inhabitants). The negative correlation observed between COVID-19 cases and this indicator has been previously reported in LAC countries10 and globally38. This finding suggests that in countries where temperatures drop, COVID-19 cases tend to increase. This could be explained by the fact that at higher temperatures, SARS-CoV-2 in aerosols decompose more rapidly39, while at lower temperatures, the virus persists longer in the environment, increasing the possibility of transmission40.

COVID-19 deaths (adjusted for population) and the Human Development Index (HDI) showed a positive correlation, contrasting with expectations, as the HDI is associated with higher life expectancy, education, and income. This positive correlation may be due to the inequality gap existing in the region10. The number of deaths from COVID-19 (adjusted per number of cases) showed a negative correlation with years of schooling, a phenomenon previously documented41. People with lower education levels have limited access to accurate information on COVID-19 prevention and face more significant barriers to implementing recommended prevention strategies42. Moreover, they are often employed in informal jobs10, making it difficult for them to stay home during the pandemic. In this sense, some important considerations regarding COVID-19 parameters are that they may not accurately reflect the situation in different countries. For instance, the number of diagnosed cases can impact adjusted parameters, leading to potential biases. This discrepancy may be explained by factors such as a decline in patient visits for laboratory testing, self-diagnosis using home rapid tests, and public fatigue toward restrictive measures. As a result, certain indicators—such as deaths adjusted per million inhabitants and deaths per million cases—may exhibit different parameter associations in correlations and generalized linear models, despite an expected relationship.

On the other hand, the COVID-19 testing indicator showed a positive correlation with male life expectancy at age 80, average population age, and a negative correlation with mortality between ages 15 and 50 and mortality before age 40. These results suggest that increased COVID-19 testing could positively affect the population, as more tests allow for earlier diagnosis and early identification and treatment of infected individuals to prevent the virus’s spread10. Furthermore, the number of COVID-19 tests performed showed a positive correlation with the elderly dependency ratio, likely reflecting the heightened care needs of this age group during the pandemic to mitigate mortality risks. The negative correlation between COVID-19 tests and temperature could be because viral respiratory infections increase during colder months, leading to a rise in laboratory testing to confirm or rule out possible causative agents.

Last, the sequencing percentages were the only COVID-19 parameter that did not show correlation or significance in the GLM with any of the 89 possible predictors. These results may be related to the number of countries (only 24) and the general low sequencing percentage in the LAC region, complicating the identification of a pattern. Unlike our results, in a global study, sequencing percentages were linked to social and economic development per capita parameters, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, socio-demographic index, and genomic surveillance capacity before the COVID-19 pandemic43.

Integration and final remarks

During the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented generation of genomic data was observed compared to other pathogens. Despite limited access to resources for genomic surveillance (infrastructure, human resources, consumables, etc.) in LAC, most countries in this region joined individual and collective efforts to generate information to aid epidemiological decision-making regarding the pandemic. Thus, countries in LAC implemented a diversity of strategies to combat COVID-19 pandemic, with mixed success and significant challenges. As summarized in44,45,46, Argentina’s early quarantine measures strengthened hospital services and fostered coordination, while Brazil utilized its surveillance system and rapidly increased hospital capacity. Chile achieved low death rates with dynamic quarantines and adequate ICU availability. In terms of genomic surveillance, Chile and Brazil provided protocols used regionally to amplify and sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genome47,48. Both also provided significant number of viral genome sequences in the region. Colombia expanded testing and ICU capacity and supported vulnerable populations through a national fund. Costa Rica’s Ministry of Health provided strategic leadership, facilitating public–private collaboration and mitigating socioeconomic impacts. Both, Costa Rica and Brazil consolidated bioinformatics protocols to assembly and compare SARS-CoV-2 genomes, which were used in several regional studies13,14,49,50,51. Ecuador centralized emergency response coordination, and Mexico maintained public awareness through daily updates by a health undersecretary. In Peru, strong presidential leadership prioritized health, expanded testing, and supported low-income groups. Besides, Peru helped Bolivia to obtain the first genome sequences of the country13. However, challenges abounded in LAC44. Weakened health system of Argentina strained businesses, and Brazil faced testing and ICU capacity issues exacerbated by political tensions. In Chile, regional policy inconsistencies and resource shortages heightened transmission risks. Colombia experienced political discord and inconsistent adherence to restrictions. Costa Rica grappled with resource shortages and economic pressures, while Ecuador’s response was undermined by economic recession and healthcare budget cuts. Mexico faced health service gaps due to reforms and socioeconomic disparities, alongside conflicting governmental messages and rising crime. Peru struggled with a fragmented health system, overcrowding, rural migration, and inconsistent mortality reporting.

These varied outcomes highlight the need for robust health systems, clear communication, and political unity to manage public health crises effectively, including regional collaborations13. In this sense, several efforts arisen from a diversity of organizations to face the pandemic in LAC. Coordination across the health system with international units was essential to controlling and then treating COVID-19 and will be key for future pandemics and global emergencies52. Collaboration and coordination among healthcare professionals, public health officials, researchers and policymakers aids efforts to deliver health services at all levels, especially in a public health crisis13. This includes sharing information, resources, and expertise, as well as implementing consistent measures and guidelines to prevent the spread and management of the virus46.

From a regional and global point of view, a diversity of organizations were pivotal in assisting LAC countries to control the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and facing the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), in collaboration with reference and public health laboratories in the region’s countries, established the Regional COVID-19 Genomic Surveillance Network (COVIGEN), which aimed to improve sequencing and generate timely genomic data19,53.

From February 2020 to March 2022, COVIGEN fostered the generation of 126,985 SARS-CoV-2 genomes in 32 countries29. During the first two years of the pandemic, approximately 43% of all SARS-CoV-2 genomes in the LAC region were produced by PAHO-backed laboratories, highlighting the importance of international collaboration networks29. To December 2024, 591,977 virus sequences are reported in LAC members of PAHO54. Despite the high quantities of available genomes, deep and complete phylogenomic studies in the region are scarce, and there are still open discussions related to the quality of assembled genomes55.

The network, later extended to respiratory viruses and called Respiratory Virus Genomic Surveillance Regional Network (RESVIGEN), is an initiative that enhances sequencing capabilities to track virus evolution, support diagnostics, and inform vaccine development, as implemented for the SARS-CoV-2. The network includes 33 regional and national labs, in which seven are reference sequencing laboratories (they support sequencing of other external laboratories within the network) for LAC: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Brasil), Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile (Chile), Instituto Nacional de Salud (Colombia), Instituto Costarricense de Investigación y Enseñanza en Nutrición y Salud (Costa Rica), Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos (México), Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud (Panamá) y University of the West Indies (Trinidad y Tobago). All the 33 participating laboratories receive training and technical support to analyze variants and mutations of public health concern, as well as promotes collaboration among countries to better understand the epidemiology of respiratory viruses54. In terms of vaccination, PAHO also supported the manufacture of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines and warrantee vaccine supplies within the LAC region45.

On the other hand, as viral genomic surveillance capacity was minimal in most Caribbean countries until December 2020, the project "COVID-19: Infectious disease Molecular epidemiology for Pathogen Control & Tracking" (COVID-19 IMPACT) was created in Trinidad and Tobago, which provided SARS-CoV-2 sequencing services in the region56.

Additionally, the CABANAnet initiative57, a project aimed at strengthening bioinformatics capacities in Latin America (https://cabana.network/), has supported SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in LAC since the pandemic began, coordinating different countries to analyze sequences and socio-environmental data, such as the present study.

Among many other initiatives, these networks are part of the regional effort to support genomic surveillance systems. This effort is crucial for low- and middle-income countries, where the infrastructure for local sequencing and human resources for data analysis must still be expanded, ensuring preparedness for future pandemics and monitoring endemic pathogens58, thereby improving the global capacity to respond to health emergencies20.

Besides, substantial portion of the global funds to address the pandemic’s impacts by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Bank were destined to LAC to meet humanitarian needs related to COVID-19 and enhance emergency preparedness and response throughout the region59,60. Other organizations provided support and efforts focus on tackling the economic, financial, and social impacts of the COVID-19 crisis through ongoing initiatives, regional projects, and targeted guidance, while upholding internationally recognized standards61. These institutions included the International Labour Organization (ILO), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Special Rapporteurship on Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Rights (REDESCA, by its Spanish acronym) of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Global Compact (UN Global Compact), and the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights. Their aim has been to protect human, labor, and children’s rights, address gender equality, safeguard the environment, and promote anti-corruption practices in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences. Thus, by working together, they stress the importance of strengthening principles to protect vulnerable communities, support sustainable recovery, and build long-term inclusive and resilient growth in the LAC region61.

Finally, this study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The main limitation lies in the reliance on data from public databases. In particular, the quality and completeness of the data extracted from the GISAID database were variable, which could influence the conclusions derived from the analysis. Additionally, the available sequences may only partially represent virus circulation in the region due to differences in sequencing rates between countries. A similar issue arises with the socio-environmental indicators, whose use was based on data availability, leading to the exclusion of others due to the lack of data for all countries, which may have resulted in the exclusion of potentially significant indicators. Lastly, using a subsample of SARS-CoV-2 sequences will only partially reflect the genetic diversity of the virus in the region, particularly in countries with limited data.

Conclusions

This study highlights the complexity of the COVID-19 emergency in the region, characterized by a diversity of variants with the predominance of some during specific periods, mainly VOCs and some recombinant cases, in line with other parts of the world. Despite the advances in sequencing and phylogenomic analysis, low sequencing rates in several countries underscore the urgent need to strengthen public health infrastructure and improve access to diagnostic technologies, such as genomic sequencing.

Additionally, the findings indicate significant correlations between 9 socio-environmental indicators across 24 LAC countries and four variables associated with cases, deaths, and diagnostic tests related to the virus in the region, although not for sequencing percentages. Our findings demonstrate that social inequalities have directly influenced the development of the COVID-19 disease. Therefore, emphasis must be placed on implementing an integrated epidemiological surveillance approach to improve preparedness for future infections that may affect the world. During the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that investment in local capabilities and international cooperation is essential to address the challenges that may arise with the emergence of new variants.

Data availability

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials (raw data and accessions for GISAID database).

References

Molina-Mora, J. A. et al. Clinical profiles at the time of diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Costa Rica during the pre-vaccination period using a machine learning approach. Phenomics 1, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/S43657-022-00058-X (2022).

Song, F. et al. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-NCoV) pneumonia. Radiology 295(1), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200274 (2020).

Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 5(4), 536–544. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z (2020).

Zhu, H., Wei, L. & Niu, P. ‘The novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan China’. , Glob. Health Res. Policy https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00135-6 (2020).

Harrison, A. G., Lin, T. & Wang, P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and pathogenesis. Trends Immunol. 41(12), 1100–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2020.10.004 (2020).

Sarker, R. et al. The WHO has declared the end of pandemic phase of COVID-19: Way to come back in the normal life. Health Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/HSR2.1544 (2023).

González-Vázquez, L. D. & Arenas, M. Molecular evolution of SARS-CoV-2 during the COVID-19 pandemic. MDPI https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14020407 (2023).

Leiva, V., Alcudia, E., Montano, J. & Castro, C. An epidemiological analysis for assessing and evaluating COVID-19 based on data analytics in Latin American countries. Biology (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12060887 (2023).

Bottan, N., Hoffmann, B. & Vera-Cossio, D. The unequal impact of the coronavirus pandemic: evidence from seventeen developing countries. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239797 (2020).

Bolaño-Ortiz, T. R. et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 through Latin America and the Caribbean region: A look from its economic conditions, climate and air pollution indicators. Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109938 (2020).

Bong, C. L. et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: effects on low- and middle-income countries. Anesth. Analg. 131(1), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846 (2020).

Ortiz-Pineda, P. A. & Sierra-Torres, C. H. Evolutionary traits and genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in South America. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8551576 (2022).

Molina-Mora, J. A. et al. Overview of the SARS-CoV-2 genotypes circulating in Latin America during 2021. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1095202 (2023).

Molina-Mora, J. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance in Costa Rica: evidence of a divergent population and an increased detection of a spike T1117I mutation. Infect. Genet. Evol. 92, 104872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104872 (2021).

OECD and World Bank Group, ‘Health at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020’, 2020.

ECLAC and CEPAL, ‘“Suriname” in Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2022’, Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2022. Accessed: Sep. 18, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/48078/10/ES2022_Suriname_en.pdf.

Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Ebrahim, S., Geffen, L. & McKee, M. Bearing the brunt of covid-19: Older people in low and middle income countries (BMJ Publishing Group, 2020).

Ibanez, A. et al. The impact of sars-cov-2 in dementia across latin america: A call for an urgent regional plan and coordinated response. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Trans. Res. Clin. Interven. 6, 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12092 (2020).

Brito, A. F. et al. Global disparities in SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 7003. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33713-y (2022).

Carter, L. L. et al. Global genomic surveillance strategy for pathogens with pandemic and epidemic potential 2022–2032. Bull. World Health Organ. 100(4), 239-239A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.22.288220 (2022).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), ‘Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: first update’, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://cov-lineages.org

Chen, Z. et al. Global landscape of SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance and data sharing. Nat Genet 54(4), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-022-01033-y (2022).

Vavrek, D. et al. Genomic surveillance at scale is required to detect newly emerging strains at an early timepoint. MedRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.12.21249613 (2021).

Salazar Mather, T. P. et al. Love in the time of COVID-19: negligence in the Nicaraguan response. Lancet Glob Health 8(6), 773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30131-5 (2020).

Ling-Hu, T., Rios-Guzman, E., Lorenzo-Redondo, R., Ozer, E. A. & Hultquist, J. F. Challenges and Opportunities for Global Genomic Surveillance Strategies in the COVID-19 Era. Viruses 14(11), 2532. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14112532 (2022).

Gozashti, L. & Corbett-Detig, R. Shortcomings of SARS-CoV-2 genomic metadata. BMC Res. Notes https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-021-05605-9 (2021).

Perbolianachis, P. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 viruses circulating in the South American region: Genetic relations and vaccine strain match. Virus Res. 311, 198688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2022.198688 (2022).

Wolf, J. M., Wolf, L. M., Bello, G. L., Maccari, J. G. & Nasi, L. A. Molecular evolution of SARS-CoV-2 from December 2019 to August 2022 (John Wiley and Sons Inc, 2022).

Gräf, T. et al. ‘Dispersion patterns of SARS-CoV-2 variants Gamma Lambda and Mu in Latin America and the Caribbean’. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 1837. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46143-9 (2024).

W. World Health Organization, ‘Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants’. Accessed: Jan. 19, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

Molina-Mora, J. A. Insights into the mutation T1117I in the spike and the lineage B.1.1.389 of SARS-CoV-2 circulating in Costa Rica. Gene Rep. 27, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GENREP.2022.101554 (2022).

Uriu, K. et al. Ineffective neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Mu variant by convalescent and vaccine sera. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.06.459005 (2021).

Molina-Mora, J. A., Cordero-Laurent, E., Calderón-Osorno, M., Chacón-Ramírez, E. & Duarte-Martínez, F. Metagenomic pipeline for identifying co-infections among distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: study cases from Alpha to Omicron. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13113-4 (2022).

Jackson, B. et al. Generation and transmission of interlineage recombinants in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Cell 184(20), 5179-5188.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CELL.2021.08.014 (2021).

Corey, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants in patients with immunosuppression. N. Engl. J. Med. 385(6), 562–566. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMSB2104756/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMSB2104756_DISCLOSURES.PDF (2021).

Desai, S. et al. An integrated approach to determine the abundance, mutation rate and phylogeny of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Brief Bioinform. 22(2), 1065–1075. https://doi.org/10.1093/BIB/BBAA437 (2021).

Banerjee, A., Mossman, K. & Grandvaux, N. Molecular Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Trends Microbiol. 29(10), 871–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TIM.2021.07.002 (2021).

Sobral, M. F. F., Duarte, G. B., da Penha Sobral, A. I. G., Marinho, M. L. M. & de Souza Melo, A. Association between climate variables and global transmission oF SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138997 (2020).

Dabisch, P. et al. The influence of temperature, humidity, and simulated sunlight on the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in aerosols. Aerosol. Sci. Technol. 55(2), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2020.1829536 (2021).

Aboubakr, H. A., Sharafeldin, T. A. & Goyal, S. M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses in the environment and on common touch surfaces and the influence of climatic conditions: A review. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 68(2), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13707 (2021).

Ribeiro, K. B. et al. ‘Social inequalities and COVID-19 mortality in the city of Saõ Paulo Brazil’. Int. J. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab022 (2021).

Alobuia, W. M. et al. Racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID-19 in the USA. J. Public Health (United Kingdom) 42(3), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa069 (2020).

Brito, A. F. et al. ‘Global disparities in SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.21.21262393 (2022).

Garcia, P. J. et al. COVID-19 Response in Latin America. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103(5), 1765. https://doi.org/10.4269/AJTMH.20-0765 (2020).

LaRotta, J. et al. COVID-19 in Latin America: A snapshot in time and the road ahead. Infect Dis. Ther. 12(2), 389–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40121-022-00748-Z/TABLES/3 (2023).

Acosta, L. D. Capacidad de respuesta frente a la pandemia de COVID-19 en América Latina y el Caribe. Rev. Panam Salud Publica https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.109 (2020).

Castillo, A. E. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of the first four SARS-CoV-2 cases in Chile. J. Med. Virol. 92(9), 1562–1566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25797 (2020).

Resende, P. C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 genomes recovered by long amplicon tiling multiplex approach using nanopore sequencing and applicable to other sequencing platforms. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.30.069039 (2020).

Aguilar-Martinez, S. L. et al. ‘Genomic and phylogenetic characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 Genomes isolated in patients from Lambayeque region Peru’. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3390/TROPICALMED9020046 (2024).

Oliveira, R. R. M. et al. PipeCoV: a pipeline for SARS-CoV-2 genome assembly, annotation and variant identification. PeerJ https://doi.org/10.7717/PEERJ.13300 (2022).

Molina-Mora, J. A. et al. Metagenomic pipeline for identifying co-infections among distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: study cases from Alpha to Omicron. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13113-4 (2022).

Touchton, M. M. et al. Learning from Latin America: coordinating policy responses across national and subnational levels to combat COVID-19. COVID https://doi.org/10.3390/COVID3090102 (2023).

Leite, J. A. et al. Implementation of a COVID-19 genomic surveillance regional network for Latin America and Caribbean region. PLoS ONE 17(3), e0252526. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252526 (2022).

PAHO, ‘RESVIGEN (Respiratory Virus Genomic Surveillance Regional Network) - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization’. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/influenza-sars-cov-2-rsv-and-other-respiratory-viruses/resvigen-respiratory-virus-genomic

Hunt, M. et al. Addressing pandemic-wide systematic errors in the SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny. biorxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.29.591666 (2024).

Sahadeo, N. S. D. et al. Implementation of genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in the Caribbean: Lessons learned for sustainability in resource-limited settings. PLOS Global Public Health 3(2), e0001455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001455 (2023).

Campos-Sánchez, R. et al. The CABANA model 2017–2022: research and training synergy to facilitate bioinformatics applications in Latin America. Front. Educ. (Lausanne) https://doi.org/10.3389/FEDUC.2024.1358620/BIBTEX (2024).

Hill, V. et al. Toward a global virus genomic surveillance network. Cell Host Microbe 31(6), 861–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2023.03.003 (2023).

World Bank, ‘World Bank’s Response to COVID-19 (Coronavirus) In Latin America & Caribbean’. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/factsheet/2020/04/02/world-bank-response-to-covid-19-coronavirus-latin-america-and-caribbean

UNICEF, ‘Latin America and the Caribbean Region Appeal’. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.unicef.org/appeals/lac

International Labour Organization, ‘Joining forces in Latin America and the Caribbean to help minimise the Coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis and foster responsible and sustainable businesses’. Accessed: Dec. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ilo.org/resource/statement/joining-forces-latin-america-and-caribbean-help-minimise-coronavirus-covid

Funding

This work was funded by The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation (grant number 2022–316,296) to support CABANAnet (project C3501 Universidad de Costa Rica), and the Universidad de Costa Rica, with the projects “C0196 Protocolo bioinformático y de inteligencia artificial para el apoyo de la vigilancia epidemiológica basada en laboratorio del virus SARS-CoV-2 mediante la identificación de patrones genómicos y clínico-demográficos en Costa Rica (2020–2024)” and "C5027 PAM-IA: Patrones moleculares y clínico-demográficos en bases de datos masivos del CIHATA asociadas a tres patologías estudiadas con inteligencia artificial".

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C.G., A.H.E., D.F.D.P., R.C.S., and J.A.M.M. participated in the conception and design of the study. M.C.T. and J.A.M.M. performed experimental assays and data analysis. M.C.T. and J.A.M.M. drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in its revision and the final approbation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Concha-Toloza, M., Collado González, L., Herrera Estrella, A. et al. Genomic, socio-environmental, and sequencing capability patterns in the surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Latin America and the Caribbean up to 2023. Sci Rep 15, 14607 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98829-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98829-9