Abstract

Studying the relationship between coseismic slip and aseismic creep helps better understand the seismic and aseismic behavior of crustal faults. We use multi-platform synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and global positioning system data to invert for the coseismic fault slip of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake in western China. Our results indicate that the earthquake ruptured two asperities, which were separated by a ~ 10-km-long slip gap. InSAR observations (2014–2016) before the earthquake show two aseismic creeping sections along the Muji fault. The western creeping section overlapped with the coseismic slip gap, and the eastern creeping section marked the eastern termination of the earthquake rupture. The spatial coincidence of creep with coseismic slip gap suggests aseismic slip might arrest and act as a barrier to seismic rupture propagation. Moreover, we observe that the creep rate along the western creeping section was similar before and after (2017–2020) the earthquake, while it accelerated along the eastern creeping section after the earthquake. Creep rate acceleration along the eastern creeping section is likely to be promoted by positive Coulomb stress changes. InSAR time-series data show that the promotion has lasted several years and is perhaps long lasting, highlighting a need to reassess the aseismic slip behavior and seismic potential along creeping faults with large historical earthquakes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ample observations document slip on a fault plane is seismic and/or aseismic, the two modes of slip complementing each other in time and space to accommodate the long-term fault motions1. Although seismic ruptures do not seem to obey the same systematic behaviors, many studies have shown that coseismic slip often overlaps with patches that are locked during the interseismic period, such as the 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku‐oki (Japan) earthquake and 2010 Mw 8.8 Maule (Chile) earthquake which ruptured regions that were predominantly locked before the event2,3. The coincidence between seismic slip and interseismic coupling frames many of our studies of earthquake potential along faults in various tectonic settings4.

Interaction between coseismic slip and aseismic slip has been observed and discussed1,5. For instance, geodetic observations along the Central Peru and Sumatra megathrusts reveal that large megathrust ruptures tend to arrest systematically when they enter areas of aseismic creep1,6,7.This type of process has also been observed on continental faults, such as that during the 2017 Mw 6.5 Ormoc earthquake along the creeping segment of the Philippine fault8. Nonetheless, the above observation is not conclusive as spontaneous rupture simulations show that even creeping regions could rupture as a result of dynamic weakening9. This theoretical process is supported by experiments on fault rocks in the laboratory10. Furthermore, Thomas et al.11 observed that the seismic rupture of the 2003 Mw 6.8 Chenkung earthquake, on the Longitudinal Valley fault in Taiwan, propagated partially into a zone of aseismic creep. Here in this study, we focus on the interaction of coseismic slip and fault creep, which is the situation where the opposite of a fault slips aseismically at surface without producing earthquakes. The creep depth can reach several kilometers (below the typical seismogenic zone width) to more than ten kilometers (approximate the seismogenic zone width)5.

The response of aseismic creep (i.e., creep rate) to coseismic rupture constitutes another aspect of the interaction between the two. Coseismic stress triggered creep on previously locked faults which tends to decay rapidly over time, such as the triggered creep which continued for only about 1 year following the 2014 Mw 6.0 South Napa, California earthquake, indicating short-term (months) influence of stress perturbations on fault creep behaviors12. Oppositely, stress perturbations from large earthquakes might have longer‐term (on 10-years scale) effects on pre-existing creeping segments13,14, examples like the surface creep rates decrease along the southern San Andreas fault in 1992–2017 which was probably to related to the stress drop induced by major earthquakes surrounding the fault15. The effect of stress loading on pre-existing creep, i.e., promote creep rate, has been observed occasionally, but the timescale is not well determined14. Forward modeling of stress changes on creeping faults shows that when the stress loading exceeds a certain threshold, a multiyear increase of fault creep rate occurs15. Continuous observations help to better investigate how the time‐dependent creep behaviors are influenced by stress perturbations from large earthquakes.

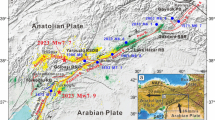

The Mw 6.6 Muji, western China, earthquake (also named as Aketao earthquake) on November 25, 2016, provides a unique opportunity to study the potential interaction between coseismic slip and aseismic creep (Fig. 1). The earthquake occurred on the Muji fault, which is a transform structure (right-lateral, ~ 6–9 mm/a slip rate) that accommodates the east–west extrusion of the northern Pamir Plateau16,17. The earthquake ruptured two seismogenic asperities, which were separated by a ~ 10-km-long slip gap along the fault distance18. Previous source modeling suggests either variable geometry17,19 or frictional property variations along strike20,21 were responsible for the rupture segmentation. The possible influence of aseismic creep in arresting the earthquake rupture is not yet evaluated, given the sparse global positioning system (GPS) observations before the earthquake are insufficient to identify coupling variations along the Muji fault. interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) observations are needed to identify whether certain sections of the Muji fault were creeping before the earthquake and whether aseismic slip acted to arrest the earthquake rupture.

The seismotectonic setting of the Pamir Plateau. The bold black line shows the Muji fault; the dark green lines represent the Kongur Extensional System (KES). Gold lines indicate the Pamir Thrust System (PTS). Thin black lines represent secondary faults. Focal mechanism solutions (Mw ≥ 5.5, 2014–2020) came from the Global Centroid Moment Tensor (GCMT). The yellow star represents the epicenter of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. The green triangles represent two sections of surface fault deformation with a length of several tens of meters22. Blue dotted lines outline the coverage of interseismic synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images. Black dotted rectangles show the footprint of the coseismic SAR images. Black arrows show Global Positioning System (GPS) site velocities with respect to the Alai basin, which is to the north of the Muji fault, with error ellipses showing 67% confidence levels. The tomato-colored circles indicate aftershocks within 1 month after the Muji earthquake (https://data.earthquake.cn). MF is the abbreviation of Muji fault; KYTS is short for Kashgar‐Yecheng Transfer System. E. PAMIR, East Pamir; C-W. PAMIR, Central-West Pamir.

In this study, we comprehensively process the InSAR images across the Muji fault spanning the periods before (2014–2016), during, and after (2017–2020) the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. We aim to derive the velocity fields before and after the earthquake to discuss the possible relationship between rupture segmentation and aseismic creep, and coseismic stress perturbation and creep rate variation. We first process multi-sensor SAR data and collect coseismic GPS offset data to invert for the finite slip of the Muji earthquake. Second, we integrate published interseismic GPS velocity solutions and process one track of descending Sentinel SAR images crossing the Muji fault. These datasets allow us to investigate if aseismic creep occurred on the Muji fault before the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake, and to further probe if it played a role during the earthquake. Moreover, we gain insights into the interaction between coseismic stress perturbation and creep rate variation. The discussion of the seismic behavior of the Muji fault is presented at the end. Our results, although derived from a case study of a moderate earthquake, provide us with a better understanding of fault slipping behaviors.

Data and methods

Coseismic deformation and source model of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake

The Muji fault

Field observations immediately after the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake confirmed that the earthquake occurred on the Muji fault, and identified two sections of surface-faulting deformation with a length of several tens of meters22. The Muji fault is a dextral strike-slip structure that connects the Kongur normal fault system to the east, the major normal fault within the Pamir Plateau23. Early geological investigations determine a slip rate of 4.5–11 mm/a along the Muji fault16. A recent field investigation proposes strike-slip and vertical (normal motion) rates of ~ 6–9 mm/a and ~ 0.3 mm/a respectively17. GPS observations confirm dextral-dominated motion along the fault (Fig. 1), with a slip rate estimated at 9.4 ± 2.5 mm/a18. During the observational period (2014–2021) of Sentinel SAR, three Mw ≥ 6.0 earthquakes occurred in the areas surrounding the Muji fault. The impact of co- and post-seismic deformation caused by these earthquakes on SAR data processing is explained below (see section "Results").

InSAR and GPS data

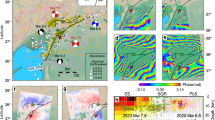

We use ascending- and descending-orbit data from the Sentinel-1 satellites to image the coseismic deformation of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake in line-of-sight (LOS). Besides, one track of ascending Advanced Land Observing Satellite-2 (ALOS-2) SAR data is adopted to gain constraint from different viewing geometry (Fig. 2). Table 1 lists the parameters of SAR data. We use the GAMMA software package to process the SAR data. The ALOS-2 data are processed following a standard differential interference strategy19. Sentinel-1 data are acquired in the terrain observation with progressive scan (TOPS) imaging mode, which requires co-registering single-look complex (SLC) images at a fine resolution. Consequently, alignment of single-look complex images, interferogram generation, filtering, and unwrapping, are employed24. Interferograms of the coseismic deformation of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake are shown in Fig. S1.

Geodetic observation, model prediction and residuals. (a), (d) and (h) show the observed InSAR displacements. (b), (e) and (i) show the model predictions. (c), (f) and (j) show the corresponding residuals. (k) Black arrows are the observed GPS site displacements; red arrows represent the model predictions. (l) shows the residuals of GPS data, error ellipse indicates 95% confidence level. The red star corresponds to the epicenter of the Muji earthquake (U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]), and the black line indicates the surface trace of our source model.

The coseismic GPS offsets data (Fig. 2k), including seven GPS stations, are obtained from Li et al.25. Raw GPS observations are processed using the GAMIT/GLOBK software. Coseismic displacement at each GPS site is estimated as an offset parameter in coordinate time series fitting. Since most GPS stations were measured in campaign mode, we only used the horizontal components to maintain a high signal–noise ratio.

Finite slip model

We use a constrained least-squares algorithm to fit the ground displacement data (i.e., InSAR and GPS). The algorithm is implemented as the Steepest Descent Method (SDM) software package26. We construct our fault model (length of 74 km and depth of 20 km) following the surface trace of the Muji fault. With reference to previous studies, we adopt a southward dip angle of 80° for the fault18,21,27. The fault is discretized into patches of 2.5 km along both strike and dip. To avoid abrupt nonphysical variations in slip inversion, a penalty parameter of 0.08 on the smoothing regularization is applied, which achieved a balance between model roughness and smoothing24 (Fig. S2). The relative weights of InSAR and GPS are equal. Despite different weighting of data would artificially emphasize the importance of a certain type of data, in our trial-and-error inversions, the main features of the coseismic slip (Fig. 3) remain regardless of variations in the weight of data.

Coseismic fault slip of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. The upper panel shows the distribution of aftershocks within 1 month after the earthquake (https://data.earthquake.cn). The lower panel shows the coseismic fault slip of the Muji earthquake. Circles in light blue represent the aftershocks on the fault plane. White arrows show the coseismic slip direction.

Interseismic geodetic data and modelling

Interseismic GPS data and block model

Interseismic GPS site velocities are used to constrain a regional kinematic block model, with the aim to investigate if the locking depth of the Muji fault changes along strike before the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. The interseismic GPS velocity solution is an integration of several published solutions28,29,30,31,32. Since these GPS velocity solutions are expressed under different reference frames, we combine them into a single consistent solution by solving for Euler vectors which minimize the velocity residuals between co-located sites. During the process, the Wang and Shen32 solution is chosen as the master solution. Figure S3 shows the final velocity field in and around the Pamir Plateau. A simple reference frame translation, relative to the Alai basin to the north of the Muji fault, highlights the dextral motion across the Muji fault (Figs. 1 and 4).

With reference to studies of the seismotectonics of the Pamir33,34. we construct a regional kinematic block model, consisting of four elastic blocks, of the Pamir and Tien Shan (Fig. 5). Block boundaries coincident with main faults in this region (Fig. S4). Text S1 presents details of the block model. We used the Tdefnode package35 for the kinematic block modeling. Considering the sparse distribution of GPS stations, we did not invert for the fault coupling along block boundary faults but instead adopted a uniform fault locking depth for those faults. We increased the fault locking depth values from 1 to 30 km (1 km step) to investigate if models with uniform locking depth could fit GPS observations reasonably, that is, to explore whether the Muji fault was locked uniformly along strike before the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake.

The left panel shows the block model of the Pamir-Tien Shan. Bold gray lines indicate block boundaries. Arrows in black show GPS observations; arrows in cyan represent model predictions; red arrows represent GPS velocity residuals. Blue arrows indicate strain rates. The right panel is an enlarged map around the Muji fault, whose position is outlined by the dotted rectangle in the left panel. E. PAMIR, Eastern Pamir block; C. PAMIR, Central Pamir block; W. PAMIR, Western Pamir block; F. PAMIR, Front Pamir block.

Interseismic InSAR data and cross-fault velocity modeling

Sentinel-1 unwrapped and geocoded interferograms and corresponding coherence data were processed by LiCSAR and published on the COMET-LiCSAR web portal36. We selected the descending track (T107) crossing the Muji fault for further processing (Figs. 1 and S5). The LiCSBAS software package was used for the InSAR time series analysis following the small baseline subset (SBAS) scheme37. During the data processing, we used the Generic Atmospheric Correction Online Service (GACOS) model38 to simulate and remove the atmospheric phase delays from the interferograms. To reduce the impact of unwrapping errors, pixels with a coherence of ≤ 0.2 in the unwrapped data were masked. We also discarded images that were seriously incoherent. The LOS rate maps spanning 2014–2016 and 2017–2020 across the Muji fault were then derived (Fig. 6).

InSAR line-of-sight (LOS) rate maps across the Muji fault. (a) LOS rate map before (2014–2016) the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. The red dotted rectangle outlines the position of an enlarged map (right below) across the Muji fault. (b) LOS rate map after (2017–2020) the Muji earthquake. The red dotted rectangle also outlines the position of an enlarged map (right below) across the Muji fault. The light blue and orange triangles in the lower right panel show the position of cross-fault profiles in Fig. 8.

During 2014–2016, two large earthquakes (the 2015 Mw 7.2 Murghab and 2016 Mw 6.4 Nura earthquakes) occurred in the study region (Figs. 1 and 6); both earthquakes caused significant coseismic deformation that was confined around their epicenters but away from the Muji fault39,40. In our data processing, postseismic deformation was detected following the 2015 Mw 7.2 Murghab earthquake, but it did not affect the region around the Muji fault. Because we focus on the short wavelength deformation (i.e., creep) across the Muji fault, long wavelength deformation associated with those earthquakes was not corrected. Note that although no obvious postseismic deformation of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake was identified18, interferograms within 6 months after the earthquake were discarded in our data processing.

We used the LOS data to investigate if any creep occurred along the Muji fault. The creep rate was defined as the fault-parallel velocity offset across the fault. Since the Muji fault is dominated by strike-slip motion and strikes approximately east-westward, the LOS data were assumed to be purely related to fault-parallel motion41. LOS velocities were taken in small boxes crossing the fault (2 km normal to the fault and 5 km along strike). We tested multiple choices of profile length on either side of the fault to estimate the creep rate (i.e., 1–5 km normal to the fault), and varied the mask width from 0.1 to 0.5 km (i.e., we explored how much data to mask out near the fault; Fig. S6). Text S2 presents more details and analysis of this process. In our preferred scheme, the profiles extend for 2 km on either side of the fault, and pixels within 0.2 km of the fault trace were masked. For each profile, we performed a linear regression to fit a straight line on each side of the fault, and the creep rate was estimated by the difference of the modeled fault-parallel velocities (x = ± 0.2 km) across the fault.

Results

Finite fault slip modeling result

Figure 2 shows the geodetic observations, model predictions and residuals. Figure 3 shows the coseismic slip model of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. Several main features are found. First, the earthquake was dominated by dextral slip, consistent with the focal mechanism reported by public agencies (e.g., the U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]). Second, our result confirms two separate ruptured asperities, suggesting two sub-events and rupture segmentation during this earthquake. Third, both slip patches ruptured several kilometers along the surface (~ 40 cm slip), which was attested by the field survey immediately after the earthquake22. Finally, a slip gap extending ~ 10 km along strike exists between the two slip patches. Those features are consistent with previous inversion results using InSAR data18,42. Furthermore, we note that most of the aftershocks were distributed around the main ruptures, probably indicating that they were driven by coseismic stress loading. A small number of aftershocks overlapped the coseismic slip region, which possibly reflect insufficient elastic strain release in local regions by the main shock. Taking a shear modulus of 30 GPa, the geodetic moment magnitude was estimated at 6.61. Note that since the InSAR data were observed at least 12 days after the main shock, they inevitably contain post-seismic deformation. Nevertheless, given the relatively small magnitude, the slip distribution was not greatly affected.

Interseismic GPS data modeling results

To investigate if variation of interseismic fault coupling along the Muji fault contributed to the rupture segmentation during the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake, two GPS velocity profiles were constructed across the fault (Fig. 4). Both velocity profiles show right-lateral slip rate of ~ 10 mm/a across the Muji fault. Despite the low spatial resolution of GPS stations especially near the fault, a sharp velocity gradient across the fault is seen in the western profile, whereas a gradual velocity change is found in the eastern profile. The above comparison indicates that the fault locking depth might vary along the strike.

To further verify the above inference, a regional kinematic block model was constructed (Fig. 5). We increased the uniform fault locking depth from 1 to 30 km with 1 km step. Since GPS sites are in the far-field, so they are not sensitive to locking depth variation, but can constrain well the slip rate. These models show a strike-slip rate of 9.8 ± 0.9 mm/a along the Muji fault, which overlaps with the geological estimate17. Besides, results show that block model could reasonably fit the GPS observations except at the NJ06 site, which is ~ 10 km away from the Muji fault (Fig. 5), where only ~ 50% of the displacement at the NJ06 site could be fitted (Fig. S7). This observation suggests that locking state of the Muji fault might be heterogeneous, yet more observations are needed, which are discussed below using InSAR data.

Fault creep rate estimated from InSAR

Results of surface creep rate along the Muji fault estimated from InSAR data are shown in Fig. 7. Figure S8 shows examples of cross-fault profiles and linear fittings. Two aseismic slip sections along the Muji fault are found both before and after the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake; the western (~ 74.17–74.3° E) and eastern (~ 74.5–74.6° E) creeping sections extend laterally of ~ 14 km and ~ 10 km respectively. The western section had a creep rate of ~ 3.8–7.2 mm/a before the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake; the creep rate (~ 3.7–6.1 mm/a) after the earthquake remained almost unchanged; besides, this section is coincident with the slip gap during the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. The creep rate of the eastern section was estimated at ~ 3.0–4.6 mm/a before the earthquake, and nearly doubled (~ 4.0–8.5 mm/a) after the earthquake; this section marked the eastern end of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake rupture. Further discussions on the relationship between aseismic creep and earthquake rupture are given below.

Discussion

Rupture segmentation of the 2016 Muji earthquake

Rupture segmentation of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake has been identified and verified by previous studies18,20,21,27,42 (Fig. 3). Several hypotheses were proposed to explain the slip gap or partial rupture. For example, heterogeneous friction and inherent strength/stress on the fault plane were suggested by Wang et al.20 and Zhang et al.21 respectively; however, no observational and simulation evidence supporting the above inferences were found along the Muji fault. Other possible factors include rupture directivity and past rupture history42, for the former, inversion result of the spatiotemporal rupture process of this event shows unilateral rupture21, while the slip gap was located in the direction of the earthquake rupture; for the latter, rupture history of the Muji fault remains largely unknown and thus could not be assessed. In short, the above factors could not fully explain the rupture segmentation during the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake.

Our results (Figs. 3 and 7) indicate that the coseismic slip gap of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake overlapped with the western creeping section; besides, the eastern creep section marked the position where the coseismic rupture terminated. The spatial coincidence of creep with the coseismic slip gap (and rupture termination) seems to suggest aseismic slip acted to arrest seismic rupture propagation. Here, a crucial step to reach the above inference is to determine the creep depth. We thus conducted two cross-fault LOS velocity profiles across these two creeping sections, and inverted for the apparent creeping depth using a simple 2D dislocation model43,44. Results (Fig. S9) show that the western and eastern sections were creeping above depths of 14.7 ± 3.6 km and 11.4 ± 4.8 km respectively before the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. The creep depths overlapped with the coseismic rupture depth (~ 5–15 km, Fig. 3). Furthermore, creep accounted for ~ 39–73% (western creep section) and ~ 31–47% (eastern creep section) of far-field loading rate of the Muji fault before the earthquake, indicating that a considerable part of strain was released aseismically. The above evidence seems to support that fault creep was likely to arrest the coseismic rupture of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that other factors, such as frictional properties and background stress state on the fault plane, were also involved.

Figure 7 further shows that the westward coseismic slip terminated near the ~ 18° fault bend, suggesting that variable fault geometry along strike might also exert a control on seismic rupture termination17. In short, both aseismic creep and fault geometry might play a role in arresting the earthquake rupture.

Long-term feature of the promoted fault creep

The identified aseismic creep shows two intriguing features. The first is that the creep rate of the eastern section was significantly accelerated or promoted after the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake, at least spanning the 2017–2020 period. Two mechanisms were likely to be responsible for the creep rate acceleration, namely the dynamic stress or static stress changes45. Despite the fact that we did not conduct kinematic rupture inversion of this earthquake, we learned from earthquake cases studies that dynamic stress changes are short-lived and vanish within minutes46, thus are more prone to cause creep rate variations within a short time of a few months47,48. The short-term effect seems to be inconsistent with the result we have observed, that is, that the increased creep rate has lasted for at least 3 years.

Alternatively, the creep rate variation was probably related to the static stress perturbations on the fault plane. Figure 7 shows coseismic Coulomb stress loading on the eastern creeping section. The above inference seems to be further supported by the distribution of aftershocks along this section. Figure 3 shows that very few aftershocks occurred along the eastern creeping section, where the calculated Coulomb stress changes were positive, perhaps indicating that the coseismic stress loading was not released by aftershocks and/or afterslip but was preserved to promote aseismic slip (i.e., creep). Here, whether the promoted creep is a short-term feature12 (i.e., decay rapidly over time to negligible amounts within months) or a long-term feature15 (i.e., a multiyear increase) is still unknown at this step. We thus investigated the time dependence of the InSAR‐derived LOS velocity. We took the difference between two points directly on either side of the eastern creep section (Fig. 6); these two points are ~ 0.2 km away from the fault so they are sensitive to the fault creep. Figure 8 shows the differential LOS displacement across the fault as a function of time. Both a linear model and a quadratic model can fit the data well. The result seems to support that the promotion of creep rate by coseismic Coulomb stress loading is long-term, even quadratic fitting shows a slow time-dependent rate decay.

The relative InSAR LOS time series data across the Muji fault. The light blue and orange circles represent short profiles (shown in Fig. 6) across the eastern and western creeping sections respectively. The black dotted lines are the best fit linear model, and the red dotted curves are the best fit quadratic model. Note that the orange circles have been shifted for clarity.

The above observation and inference have important implications. In the context of aseismic fault creep worldwide (see the review paper by Harris5), a large part of creep occurs on faults that ruptured during large earthquakes, such as the North Anatolian fault49 and the Xianshuihe fault50. Considering the long-term, perhaps several years to decades, promotion effect of stress perturbation on fault creep, the current creep rate we observed does not necessarily represent its steady rate in the interseismic period51; this might lead to deviations in our understanding of fault creeping behaviors, and underestimate the seismic potential along creeping faults. More geodetic observations that span a longer period help better resolve the time dependence of fault creep.

The second intriguing feature relates to the creep rate along the western section. Different from the creeping behavior along the eastern section, the creep rate of the western section did not change significantly after 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. One plausible scenario was that coseismic stress loading along this section was released by aftershocks and/or afterslips, as clustered aftershocks occurred following the main shock (Fig. 3); the stress state of this section might quickly recover to its pre-event state, thus allowing for a similar creep rate. The differential LOS displacement time series do not show a time-dependent decay but a linear-like character (Fig. 8), supporting the above hypothesis. Alternatively, the creep rate along this section was accelerated right after the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake but decayed rapidly to its pre-event state. Because SAR images within 6 months after the earthquake were discarded in our data processing, we cannot distinguish between the above two hypotheses for the time being. Processing the SAR data immediately after the earthquake is our next step to identify possible postseismic deformation and creep rate changes.

Implications to seismic behavior along the Muji fault

Field investigations identified displaced landforms along the Muji fault17, indicating that either historical earthquakes ruptured to the surface, or the fault had obvious aseismic creep over earthquake cycles. Our geodetic modeling results (Fig. 7) show that the coseismic slip of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake and the aseismic slip complemented each other on the shallow part of the Muji fault. The above results seem to imply that the cumulative deformation along the fault was formed both seismically and interseismically; however, this hypothesis relies on the creeping behaviors.

If the identified aseismic creep represents a long-lasting behavior, that is, persists through earthquake cycles, the creeping sections might act as permanent barriers to arrest seismic rupture propagation. In this case, depending on whether asperities rupture separately or in combination, an earthquake along the Muji fault could either be a single asperity rupture event or a cascade rupture like the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. Alternatively, an earthquake ruptures the entire Muji fault; that is, the seismic rupture propagates through the fault bend (Fig. 7) and results in an earthquake with a larger magnitude (Mw 7.2 according to the scaling relationship between magnitude and rupture length from Wells and Coppersmith52). In short, whatever the earthquake or rupture scenarios are, both coseismic surface rupture and aseismic creep contribute to the geomorphological offsets observed along the Muji fault.

Alternatively, if the aseismic creep is a short-term or transient feature, namely, the creep lasts only for years to decades, cumulative deformation along the Muji fault should be formed mainly by earthquake surface ruptures. In this case, the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake should not be regarded as a characteristic event along the Muji fault, as it caused limited surface ruptures/offsets (Figs. 3 and 7). Consequently, earthquakes of larger magnitudes with obvious surface-faulting deformation should be expected along the Muji fault.

Our current results cannot distinguish between the above two hypotheses. A better understanding of seismic behavior and associated seismic hazard of the Muji fault requires analyzing the time-dependent behavior of the aseismic creep, and additional constraints of the rupture history of the fault.

Conclusions

We used multi-platform SAR and GPS data to invert the source parameters of the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. Coseismic inversion result shows the earthquake was dominated by dextral slip, with two slip patches separated by a ~ 10-km-long slip gap.

Then we processed the descending InSAR images crossing the Muji fault and obtained LOS rate maps before and after the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. By modeling cross-fault LOS velocity profiles, we identified two creeping sections along the Muji fault before the earthquake; of which the western creep section (creep depth of 14.7 ± 3.6 km) overlapped with the coseismic slip gap, and the eastern creep section (creep depth of 11.4 ± 4.8 km) coincident with the eastward earthquake rupture termination. The above results suggest aseismic creep was likely to arrest the earthquake rupture propagation.

We also analyzed the creep rate variation along both creep sections. The western creep section had a creep rate of ~ 3.8–7.2 mm/a before the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake and remained almost unchanged after the earthquake. The eastern creep section had a creep rate of ~ 3.0–4.6 mm/a but nearly doubled (~ 4.0–8.5 mm/a) after the earthquake. The accelerated creep rate along the eastern section was most likely to be caused by coseismic Coulomb stress loading, whose effect might be long-term. The Muji earthquake provides us with unique observational evidence for studying the interaction between coseismic slip and aseismic creep.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author (Z.G.) on reasonable request.

References

Avouac, J. P. From geodetic imaging of seismic and aseismic fault slip to dynamic modeling of the seismic cycle. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 43, 233–271 (2015).

Loveless, J. P. & Meade, B. J. Spatial correlation of interseismic coupling and coseismic rupture extent of the 2011 Mw = 9.0 Tohoku-oki earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L17306 (2011).

Moreno, M., Rosenau, M. & Oncken, O. 2010 Maule earthquake slip correlates with pre-seismic locking of Andean subduction zone. Nature 467, 198–202 (2010).

Kaneko, Y., Avouac, J. P. & Lapusta, N. Towards inferring earthquake patterns from geodetic observations of interseismic coupling. Nat. Geosci. 3, 363–369 (2010).

Harris, R. A. Large earthquakes and creeping faults. Rev. Geophys. 55, 169–198 (2017).

Perfettini, H. et al. Seismic and aseismic slip on the Central Peru megathrust. Nature 465, 78–81 (2010).

Rolandone, F. et al. Areas prone to slow slip events impede earthquake rupture propagation and promote afterslip. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao6596 (2018).

Dianala, J. D. B. et al. The relationship between seismic and aseismic slip on the Philippine Fault on Leyte Island: Bayesian modeling of fault slip and geothermal subsidence. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2020JB020052 (2020).

Noda, H. & Lapusta, N. Stable creeping fault segments can become destructive as a result of dynamic weakening. Nature 493, 518–521 (2013).

Kohli, A. H., Goldsby, D. L., Hirth, G. & Tullis, T. Flash weakening of serpentinite at near-seismic slip rates. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 116, B03202 (2011).

Thomas, M. Y., Avouac, J.-P., Champenois, J., Lee, J.-C. & Kuo, L.-C. Spatiotemporal evolution of seismic and aseismic slip on the Longitudinal Valley Fault, Taiwan. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 5114–5139 (2014).

Lienkaemper, J. J., DeLong, S. B., Domrose, C. J. & Rosa, C. M. Afterslip behavior following the 2014 M 6.0 South Napa earthquake with implications for afterslip forecasting on other seismogenic faults. Seismol. Res. Lett. 87, 609–619 (2016).

Lienkaemper, J. J., Galehouse, J. S. & Simpson, R. W. Long-term monitoring of creep rate along the Hayward fault and evidence for a lasting creep response to 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2269–2272 (2001).

Lienkaemper, J. J. et al. Long-term creep rates on the Hayward Fault: Evidence for controls on the size and frequency of large earthquakes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 102, 31–41 (2012).

Xu, X. et al. Surface creep rate of the southern San Andreas fault modulated by stress perturbations from nearby large events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 10259–10268 (2018).

Chevalier, M.-L. et al. Fast slip-rate along the northern end of the Karakorum fault system, western Tibet. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L22309 (2011).

Li, T. et al. Cumulative and coseismic (during the 2016 Mw 6.6 Aketao earthquake) deformation of the dextral-slip Muji Fault, northeastern Pamir orogen. Tectonics 38, 3975–3989 (2019).

Feng, W. et al. A slip gap of the 2016 M w 6.6 Muji, Xinjiang, China, earthquake inferred from Sentinel-1 TOPS interferometry. Seismol. Res. Lett. 88, 1054–1064 (2017).

Liu, Y., Gong, W., Zhang, G., Zhang, G. & Shan, X. Study of the D-InSAR deformation field and seismotectonics of the Aketao Mw 6.6 earthquake on November 25, 2016 constrained by Sentinel-1A and ALOS-2. Chin. J. Geophys. 61, 4037–4054 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Slip model for the 25 November 2016 Mw 66 Aketao earthquake, western China, revealed by Sentinel-1 and ALOS-2 observations. Remote Sens. 9, 325 (2017).

Zhang, X., Xu, L. S., Li, L., Yi, L. & Feng, W. Confirmation of the double-asperity model for the 2016 Mw 6.6 Akto earthquake (NW China) by seismic and InSAR data. J. Asian Earth Sci. 184, 103998 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Coseismic surface rupture and seismogenic Muji fault of the 25 November 2016 Aketao Mw 6.6 earthquake in northern Pamir. Seismol. Geol. 38, 1160–1174 (2016).

Robinson, A. C. et al. Tectonic evolution of the northeastern Pamir: Constraints from the northern portion of the Cenozoic Kongur Shan extensional system. GSA Bull. 116, 953–973 (2004).

Li, Y. et al. Geodetic Model of the 2018 Mw 7.2 Pinotepa, Mexico, Earthquake Inferred from InSAR and GPS Data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 110, 1115–1124 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Rupture characteristics of the 25 November 2016 Akteo earthquake (Mw 6.6) in eastern Pamir revealed by GPS and teleseismic data. Pure Appl. Geophys. 175, 573–585 (2018).

Wang, R., Diao, F. & Hoechner, A. SDM-A geodetic inversion code incorporating with layered crust structure and curved fault geometry. In EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria (2013).

He, P., Ding, K. & Xu, C. The 2016 Mw 6.7 Aketao earthquake in Muji range, northern Pamir: Rupture on a strike-slip fault constrained by Sentinel-1 radar interferometry and GPS. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 73, 99–106 (2018).

Zubovich, A. V. et al. GPS velocity field for the Tien Shan and surrounding regions. Tectonics 29, TC6014 (2010).

Ischuk, A. et al. Kinematics of the Pamir and Hindu Kush regions from GPS geodesy. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 2408–2416 (2013).

Zhou, Y. et al. Present-day crustal motion around the Pamir Plateau from GPS measurements. Gondwana Res. 35, 144–154 (2016).

Qiao, X. et al. The crustal deformation revealed by GPS and InSAR in the northwest corner of the Tarim Basin, northwestern China. Pure Appl. Geophys. 174, 1405–1423 (2017).

Wang, M. & Shen, Z. K. Present-day crustal deformation of continental China derived from GPS and its tectonic implications. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2019JB018774 (2020).

Schurr, B. et al. Seismotectonics of the Pamir. Tectonics 33, 1501–1518 (2014).

Zubovich, A. et al. Tectonic interaction between the Pamir and Tien Shan observed by GPS. Tectonics 35, 283–292 (2016).

McCaffrey, R. Time-dependent inversion of three-component continuous GPS for steady and transient sources in northern Cascadia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L07304 (2009).

Lazecký, M. et al. LiCSAR: An automatic InSAR tool for measuring and monitoring tectonic and volcanic activity. Remote Sens. 12, 2430 (2020).

Morishita, Y. et al. LiCSBAS: An open-source InSAR time series analysis package integrated with the LiCSAR automated Sentinel-1 InSAR processor. Remote Sens. 12, 424 (2020).

Yu, C., Li, Z., Penna, N. T. & Crippa, P. Generic atmospheric correction model for interferometric synthetic aperture radar observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 9202–9222 (2018).

Sangha, S. et al. Fault geometry of 2015, Mw 7.2 Murghab, Tajikistan earthquake controls rupture propagation: Insights from InSAR and seismological data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 462, 132–141 (2017).

He, P. et al. The 2016 Mw 6.5 Nura earthquake in the Trans Alai range, northern Pamir: Possible rupture on a back-thrust fault constrained by Sentinel-1A radar interferometry. Tectonophysics 749, 62–71 (2018).

Wright, T. J., Parsons, B. E. & Lu, Z. Toward mapping surface deformation in three dimensions using InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L01607 (2004).

Bie, L., Hicks, S., Garth, T., Gonzalez, P. & Rietbrock, A. ‘Two go together’: Near-simultaneous moment release of two asperities during the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji, China earthquake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 491, 34–42 (2018).

Weertman, J. & Weertman, J. R. Elementary dislocation theory 213 (MacMillan, 1964).

Segall, P. Earthquake and volcano deformation (Princeton University Press, 2010).

Du, W.-X., Sykes, L. R., Shaw, B. E. & Scholz, C. H. Triggered aseismic fault slip from nearby earthquakes, static or dynamic effect?. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 108, 2131 (2003).

Belardinelli, M. E., Bizzarri, A. & Cocco, M. Earthquake triggering by static and dynamic stress changes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 2135 (2003).

Rymer, M. J., Boatwright, J., Seekins, L. C., Yule, J. D. & Liu, J. Triggered surface slips in the Salton Trough associated with the 1999 Hector Mine, California, earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92, 1300–1317 (2002).

Wei, M., Sandwell, D., Fialko, Y. & Bilham, R. Slip on faults in the Imperial Valley triggered by the 4 April 2010 Mw 7.2 El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake revealed by InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L01308 (2011).

Çakir, Z., Akoglu, A. M., Belabbes, S., Ergintav, S. & Meghraoui, M. Creeping along the Ismetpasa section of the North Anatolian fault (Western Turkey): Rate and extent from InSAR. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 238, 225–234 (2005).

Allen, C. R. et al. Field study of a highly active fault zone: The Xianshuihe fault of southwestern China. GSA Bull. 103, 1178–1199 (1991).

Bilham, R. et al. Surface creep on the North Anatolian fault at Ismetpasa, Turkey, 1944–2016. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 7409–7431 (2016).

Wells, D. L. & Coppersmith, K. J. New empirical relationships among magnitude, rupture length, rupture width, rupture area, and surface displacement. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 84, 974–1002 (1994).

Wessel, P., Smith, W. H., Scharroo, R., Luis, J. & Wobbe, F. generic mapping tools: Improved version released. EoS Trans. AGU 94, 409–410 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the colleagues who conducted the GPS measurements. The authors thank Editor André Niemeijer and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which greatly improved the quality of this article. Coseismic GPS offset data were derived from Li et al.25. Interseismic GPS velocity solutions were integrated from published studies ([28–32]). The Sentinel-1 SAR data used for coseismic inversion were provided by the European Space Agency (ESA). The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) provided Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS)-2 data. The Sentinel-1 products used to derive interseismic LOS maps were obtained from COMET (https://comet.nerc.ac.uk/COMET-LiCS-portal/). Elastic block modeling was implemented using the Tdefnode package (https://robmccaffrey.github.io/TDEFNODE/TDEFNODE.html). All the figure were generated using the Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) software53.

Funding

This work was co-supported by the Open Fund of Hebei Cangzhou Groundwater and Land Subsidence National Observation and Research Station (No. CGLOS-2023-08), the Science and Technology Projects of Gansu Province (No. 24JRRA289, 24JRRA856, 25JRRA151) and the Innovation Fund Project for College Teachers of Gansu Provincial Education Department (No. 2025A-041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. and Z.G.; methodology, Z.G.; software, J.L.; validation, W.Y., H.G., R.L., C.Y. and D.X.; formal analysis, Z.G.; investigation, J.X., Z.G. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.X. and Z.G.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.X. and Z.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Gao, Z., Liu, J. et al. InSAR observations reveal interactions between seismic and aseismic slip during and after the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji earthquake. Sci Rep 15, 15116 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98880-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98880-6