Abstract

Soil salinization poses a significant challenge for rice farming, affecting approximately 20% of irrigated land worldwide. It leads to osmotic stress, ionic toxicity, and oxidative damage, severely hindering growth and yield. This study investigates the potential of lignin-containing cellulose nanofiber (LCNF)-selenium nanoparticle (SeNPs) hybrids to enhance salt tolerance in rice, focusing on two rice genotypes with contrasting responses to salt stress. LCNF-SeNP hybrids were synthesized using a microwave-assisted green synthesis method and characterized through FTIR, X-ray diffraction, SEM, TEM, and TGA. The effects of LCNF/SeNPs on seed germination, physiological responses, and gene expression were evaluated under varying levels of NaCl-induced salt stress. Results indicated that LCNF/SeNPs significantly enhanced the salt tolerance of the salt-sensitive genotype IR29, as evidenced by increased germination rates, reduced salt injury scores, and higher chlorophyll content. For the salt-tolerant genotype TCCP, LCNF/SeNPs improved shoot lengths and maintained elevated chlorophyll levels under salt stress. Furthermore, LCNF/SeNPs improved ion homeostasis in both genotypes by reducing the Na+/K+ ratio, which is crucial for maintaining cellular function under salt stress. Gene expression analysis revealed upregulation of key salt stress-responsive genes, suggesting enhanced stress tolerance due to the application of LCNF/SeNPs in both genotypes. This study underscores the potential of LCNF/SeNPs as a sustainable strategy for improving crop performance in saline environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change presents a major risk to global food security, with forecasts suggesting that food production must rise by 50% by 2050 to satisfy the needs of a growing population1. Rice (Oryza sativa L.), a staple for over half of the world’s population, is essential for food security and economic stability2. However, current trends in rice productivity are insufficient to meet the rising global demand3.

Exacerbated by climate change, salinity is becoming a major challenge for rice production4. Soil salinization affects approximately 20% of irrigated agricultural land worldwide5, threatening crop yields and food security. Salt stress adversely impacts rice growth, development, and yield through osmotic stress, ionic toxicity, electrolyte leakage, membrane disruption, nutrient imbalances, decreased photosynthesis, oxidative damage, and altered phytohormone production6,7,8. To mitigate salt stress, plants often close their stomata to conserve water and limit transpiration9. High salinity disrupts photosynthesis, reduces shoot and root biomass, and hampers seed germination and seedling growth. Rice genotypes exhibit variability in their tolerance to salinity, with some demonstrating greater resilience to saline conditions10. This variability is linked to complex physiological and molecular mechanisms, including ion exclusion, tissue tolerance, and osmotic adjustment5.

Salinity stress not only disrupts ion homeostasis and osmotic balance but also triggers an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals (O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (OH⁻)11. Under normal conditions, ROS are byproducts of cellular metabolism and play essential roles in signaling and defense12. However, under salinity stress, the excessive accumulation of ROS overwhelms the plant’s antioxidant defense systems, leading to oxidative stress13. ROS can severely damage to cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to membrane peroxidation, enzyme dysfunction, and DNA breakage14 .This oxidative damage impairs critical physiological processes, such as photosynthesis and respiration, ultimately reducing plant growth and yield15. To mitigate the buildup of ROS, plants activate antioxidant defense mechanisms, which include enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD), as along with non-enzymatic antioxidants like glutathione and ascorbate16. However, under severe salinity stress, the endogenous antioxidant capacity of plants is often insufficient to mitigate oxidative damage, necessitating external interventions to enhance stress tolerance17.

Salinity tolerance during the seedling stage requires the maintenance of ion balance and osmotic adjustment4. Excessive sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions in the soil can disrupt this balance by interfering with the uptake of essential ions, especially potassium (K⁺)18. High Na⁺ levels impair the roots’ ability to absorb water, creating drought-like conditions. Genes from the high-affinity K⁺ transporter (HKT) family, such as OsHKT1;1, are critical in regulating Na⁺ and K⁺ balance under saline conditions. Specifically, OsHKT1;1 helps reduce Na⁺ accumulation in shoots19,20,21. The balance between Na⁺ and K⁺ ions is maintained by SOS pathway genes and HKT transporters, which either exclude Na⁺ from the cytosol or selectively unload Na⁺ from the xylem sap22,23,24. Furthermore, genes involved in ion transport including the Na⁺/K⁺ antiporter SOS1 (Salt Overly Sensitive 1), the Na⁺/H⁺ antiporter NHX, and the K⁺ channel AKT1, are upregulated in response to salt stress5. While understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying salt tolerance is crucial, there is a growing need for practical solutions to improve the resilience of rice plants in saline environments.

Nanotechnology offers innovative approaches to addressing agricultural challenges, including salt stress. Nanoparticles, with their unique properties and potential for targeted nutrient delivery, present promising opportunities for improving plant stress tolerance and productivity. Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have shown particular promise in enhancing plant tolerance to salt stress by boosting antioxidant defense systems, regulating ion homeostasis, and protecting the photosynthetic machinery17. Other nanoparticles, such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂), silicon dioxide (SiO₂), iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), and cerium oxide (CeO₂), have also demonstrated benefits in improving resilience to salt stress25,26,27,28,29,30. These effects are attributed to mechanisms such as enhanced nutrient uptake, antioxidant production, ionic balance regulation, and gene expression modulation. SeNPs stand out due to their enhanced bioavailability and unique physicochemical properties compared to bulk selenium31. Studies indicate that SeNPs improve salt tolerance in various crops11,32, and their small size and large surface area facilitate efficient uptake and translocation within plants31,33,34. Despite these findings, the effects of SeNPs on rice, particularly under salt stress, are not yet fully understood. Moreover, the responses of different rice genotypes to SeNP supplementation remain largely unexplored. Green synthesis methods, such as microwave-assisted techniques, have gained popularity for their environmentally sustainable production of nanoparticles, resulting in more uniform size distributions and increased stability35,36.

Lignin-containing cellulose nanofibers (LCNFs), derived from mildly bleached or unbleached lignocellulosic fibers, offer numerous benefits, including high yield, reduced energy and chemical usage, and excellent environmental sustainability. Lignin nanoparticles, whether attached to the cellulose nanofiber (CNF) surface or existing freely, help stabilize nanoparticles by forming a more rigid network, with lignin acting as a binder between CNFs. To the best of our knowledge, the use of LCNFs for stabilizing SeNPs has not yet been explored37,38,39,40. Since LCNFs provide support structures for SeNPs, the unique combination of lignin and cellulose in LCNFs is expected to enhance the stability and dispersibility of SeNPs, preventing agglomeration and improving their effectiveness. By utilizing LCNFs, synergistic effects of both materials can be harnessed, particularly in mitigating salt stress. The interaction between LCNFs and SeNPs may also enhance antioxidant properties, contributing to greater resilience to salt stress in plants. This novel approach represents a significant advancement in the use of LCNFs for agricultural and environmental applications.

In this study, we evaluated the impact of LCNF/SeNPs on salt stress responses in two rice genotypes with differing salt sensitivities: the salt-tolerant TCCP and the salt-sensitive IR29. In addition to assessing the morphological and physiological responses of both rice genotypes to various concentrations of LCNF-SeNPs in alleviating salt stress, we analyzed the expression patterns of key salt stress-responsive genes.

Results and discussion

Characterization of LCNF-SeNPs

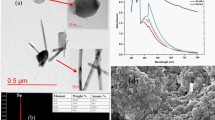

The morphology and composition of the LCNF/SeNPs composite were analyzed to gain insights into the structure and distribution of the materials (Fig. 1). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images of pure LCNF revealed interconnected nanofibers forming a network-like structure, with some fibrils agglomerating into larger aggregates (Fig. 1a)41,42,43,44. Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) appeared as dark spherical spots uniformly distributed across the LCNF matrix (Fig. 1b and c). Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of LCNF showed dense, fibrous structures (Fig. 1d), while the composite exhibited these fibrous structures along with white spherical SeNPs (Fig. 1e). The Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) spectrum (Fig. 1f) displayed peaks corresponding to carbon (C), oxygen (O), and selenium (Se), with an additional platinum (Pt) peak due to the SEM pre-coating. EDS mapping images (Fig. 1g-i) further confirmed the homogeneous distribution of C, O, and Se across the composite surface, validating the successful incorporation of SeNPs onto the surface of LCNFs.

The functional groups, thermal stability, crystallinity, and optical characteristics of both pure LCNF and the LCNF/SeNPs composite were examined using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR), Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy (Fig. 2). The FTIR spectrum of pure LCNF displayed a broad band at 3350 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the O-H stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups in cellulose (Fig. 2a). Additionally, bands at 2930 cm⁻¹ and 1643 cm⁻¹ were attributed to C-H asymmetrical stretching and O-H bending vibrations of adsorbed water molecules, respectively. In the LCNF/SeNPs composite, new bands at 1552 cm⁻¹ and 1280 cm⁻¹ appeared, indicating the formation of C-Se bonds (Fig. 2a).

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of pure LCNF revealed three distinct steps of weight loss (68.7%) between 30 °C and 600 °C (Fig. 2b). The first step, occurring between 30 °C and 200 °C, accounted for a weight loss of 8.9%, which was due to the evaporation of adsorbed water and the breakdown of volatile organic compounds. The second step, from 200 °C to 350 °C, showed a 39.3% weight loss, linked to the decomposition of anhydroglucose units and lignin components. The final step, from 350 °C to 600 °C, exhibited a 20.4% weight loss, likely caused by the pyrolysis of cellulose fibers and the remaining carbonaceous residue. In contrast, the TGA analysis of the LCNF/SeNPs composite showed two weight loss steps (58.9%), which is lower than that of pure LCNF, suggesting an improvement in thermal stability upon SeNP incorporation (Fig. 2b).

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of pure LCNF and the LCNF/SeNPs composite are shown in Fig. 2c. Pure LCNF displayed a peak at 2θ values of 22.4° and 22.8°, which corresponded to the (102) and (002) planes of cellulose I, respectively45. In contrast, the LCNF/SeNPs composite exhibited additional reflections at 2θ values of 23.6°, 29.8°, 41.4°, 43.7°, 45.5°, 48.1°, 51.8°, 56.2°, 61.7°, and 65.3°, which correspond to the (100), (101), (110), (102), (111), (200), (201), (112), (103), and (210) planes of hexagonal selenium (Se) (JCPDS No. 00-001-0853). These results confirm the successful incorporation of SeNPs into the LCNF matrix. Additionally, the crystallinity of the composite was enhanced with the addition of SeNPs. The average crystallite sizes of pure LCNF and the LCNF/SeNPs composite, calculated using the Scherrer Eqquation 46, were 15.5 nm and 31.9 nm, respectively.

The UV-Vis spectrum of the LCNF/SeNPs composite (Fig. 2d) showed an absorption peak at 281 nm, confirming the successful formation and stability of SeNPs on the surface of the LCNF matrix. This peak, along with an intense orange gel formation, further indicates the stability and uniform distribution of SeNPs in the composite47.

Rice seed germination response to salt stress and selenium supplementation

Under control conditions, both TCCP and IR29 exhibited 100% germination, confirming seed viability. However, as NaCl concentrations increased, germination rates declined significantly. TCCP demonstrated greater salt tolerance, with a germination rate of 73.8% at 100 mM NaCl, compared to 50% in IR29. Germination was completely inhibited at extreme salt stress (200 mM NaCl) (Fig. 3a). This reduction aligns with previous studies, which indicate that high salinity disrupts water uptake and triggers oxidative stress, impairing seed germination48,49.

SeNP supplementation alone did not affect germination under non-stress conditions but effectively mitigated the negative impacts of salt stress in a concentration-dependent manner. At 100 mM NaCl, SeNPs increased germination rates to 86% in TCCP and 76.6% in IR29, with lower Se concentrations (5–10 ppm) proving more effective. Under severe salt stress (150 mM NaCl), SeNPs enhanced germination to 27.5% in TCCP and 44% in IR29 (Fig. 3a, b, c). These improvements are likely due to the antioxidant properties of SeNPs, which reduce ROS accumulation and support osmotic adjustment26,48,49,50,51,52,53. However, SeNPs could not counteract germination inhibition at 200 mM NaCl, suggesting a stress threshold beyond which the plant’s defense mechanisms are overwhelmed. This indicates that while SeNPs can significantly enhance stress tolerance, their effectiveness is limited under extreme salinity conditions.

Physiological responses to salt stress and selenium supplementation

Salt stress significantly impaired physiological parameters in both rice genotypes, with the salt-sensitive IR29 showing greater susceptibility than the salt-tolerant TCCP. Chlorophyll content (CHL), a critical indicator of photosynthetic efficiency, was notably reduced under NaCl stress. In TCCP, CHL levels dropped to 19.1, while IR29 experienced a more substantial decline to 14.9, compared to their respective controls (27.0 and 29.1) (Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 4 and 5). This reduction in CHL aligns with the well-established effects of salinity on chlorophyll biosynthesis and the accelerated degradation of chlorophyll due to ROS-induced oxidative damage5. The application of SeNPs effectively preserved CHL levels, particularly in TCCP, where values remained close to control conditions across all Se treatments. In IR29, the 20 ppm Se+ NaCl treatment restored CHL levels to 28.9, comparable to control conditions, suggesting that SeNPs protect the photosynthetic machinery by mitigating oxidative stress and stabilizing chloroplast ultrastructure32. These results align with studies demonstrating that selenium enhances chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduces degradation under stress conditions54,55,56.

Shoot height (SHL), another critical growth parameter, was also negatively impacted by salt stress. In TCCP, SHL decreased to 28.4 cm under NaCl stress, compared to the control (36.8 cm), while IR29 maintained relatively stable SHL across treatments (Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 4 and 5). The reduction in SHL in TCCP underscores its sensitivity to stress, whereas the stability in IR29 suggests a shift in resource allocation toward root growth as an adaptive strategy under salinity58. SeNP supplementation improved SHL in IR29 under moderate salt stress, further supporting the role of SeNPs in alleviating growth inhibition caused by salt stress.

Salt stress also caused significant increases in shoot sodium concentration (SNC) and Na+/K+ ratios in both genotypes, with IR29 accumulating higher Na+ levels (2243 mmol kg− 1) compared to TCCP (1662 mmol kg− 1) (Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 4 and 5). This differential Na+ accumulation highlights TCCP’s superior ion exclusion mechanisms, essential for maintaining cellular ion homeostasis under salt stress10,57,58. SeNP supplementation reduced Na+ accumulation and improved Na+/K+ ratios in both genotypes, with IR29 showing a more pronounced response. This suggests that SeNPs enhance Na+ exclusion and K+ retention, particularly in salt-sensitive genotypes50,54. These improvements in ion homeostasis are likely mediated by the upregulation of genes such as NHX1 and SOS1, which are involved in Na+ compartmentalization and exclusion50.

Response of IR29 for different salt-responsive traits under six treatment levels. T1 = Control, T2 = NaCl, T3 = 10ppm Selenium, T4 = 20ppm Selenium, T5 = 10ppm Selenium + 150mM NaCl, T6 = 20ppm Selenium + 150mM NaCl. SIS, salt injury score; CHL, chlorophyll content; SNC, shoot sodium concentration; SKC, shoot potassium concentration; RNC, root sodium concentration; RKC, root potassium concentration, SNaK, ratio of the shoot sodium and potassium concentration; RNaK, ratio of the root sodium and potassium concentration. a, b represents Tukey lettering for differences in treatment levels, shared letter between the genotypes indicates no significant difference at 0.05 probability level.

Root sodium concentration (RNC) and root Na+/K+ ratios (RNaK) also exhibited significant differences between the genotypes. Under NaCl stress, IR29 accumulated higher Na+ levels in roots (2616 mmol kg− 1) compared to TCCP (1615 mmol kg− 1), further emphasizing TCCP’s superior ion homeostasis mechanisms (Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 4 and 5). SeNP supplementation effectively reduced both RNC and RNaK in both genotypes, with TCCP showing a more pronounced reduction. These findings suggest that SeNPs enhance root ion exclusion and K+ retention, which are critical for maintaining water and nutrient uptake under salinity stress10,58.

Response of TCCP for different salt responsive traits under 6 treatment levels. T1 = Control, T2 = NaCl, T3 = 10ppm Selenium, T4 = 20ppm Selenium, T5 = 10ppm Selenium + 150mM NaCl, T6 = 20ppm Selenium + 150mM NaCl. SIS, salt injury score; CHL, chlorophyll content; SNC, shoot sodium concentration; SKC, shoot potassium concentration; RNC, root sodium concentration; RKC, root potassium concentration, SNaK, ratio of the shoot sodium and potassium concentration; RNaK, ratio of the root sodium and potassium concentration. a, b represent Tukey lettering for differences in treatment levels, shared letter between the genotypes indicates no significant difference at 0.05 probability level.

The differential physiological responses of TCCP and IR29 to salt stress and SeNP supplementation highlight the importance of genotype-specific stress tolerance mechanisms. TCCP’s greater resilience is likely due to its more efficient ROS scavenging and ion homeostasis mechanisms, which SeNPs further enhance. In contrast, IR29, while more sensitive to salt stress, benefits significantly from SeNP supplementation, particularly in terms of Na+ exclusion and K+ retention. These results underscore the potential of SeNPs to improve salt tolerance in rice, particularly in sensitive genotypes, by mitigating oxidative damage and enhancing ion homeostasis50,54.

Visual evidence of salt stress and selenium supplementation effects

The visual assessment of rice genotypes IR29 and TCCP under different treatments over 4, 6, and 8 days provided key insights into stress responses and the mitigating effects of SeNPs (Fig. 6). IR29 seedlings showed noticeable wilting and chlorosis under salt stress. As the treatment progressed, these symptoms worsened, with leaves becoming increasingly yellow and curling, indicative of cellular damage and dehydration. In contrast, IR29 seedlings treated with SeNPs maintained better leaf turgor and a more vibrant green color than those exposed to salt stress alone. This suggests that SeNP supplementation helped mitigate some adverse effects of salt stress, leading to improved plant health and appearance. Over time, the difference in stress symptoms became more pronounced, with SeNP-treated plants exhibiting less severe wilting and chlorosis (Fig. 6).

Similarly, TCCP showed visible signs of stress, such as wilting and chlorosis, though these symptoms were milder than those observed in IR29. This progression of stress over time was less severe in TCCP. While damage increased in TCCP seedlings as the treatment continued, the initial impact was noticeably less pronounced compared to IR29. TCCP seedlings treated with SeNPs also displayed improved leaf turgor and color, suggesting that SeNP supplementation helped maintain better plant health. However, the visual improvements in TCCP were less dramatic than those observed in IR29. Nonetheless, SeNP-treated TCCP plants showed healthier growth and less stress-related damage than those subjected to NaCl alone (Fig. 6).

The visual documentation of plant responses highlights the beneficial effects of SeNPs, particularly for the IR29 genotype. Maintaining better leaf turgor and color in SeNP-treated plants indicates improved water retention and chlorophyll preservation - key markers of enhanced salt tolerance. Furthermore, the potential improvement in chlorophyll content and photosynthetic efficiency further supports the idea that SeNPs help maintain plant health under saline conditions11.

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression analysis was conducted on five salt stress-responsive genes—OSLOL5, NHX1, SOS1, HKT1, and HAK20 - in both rice genotypes, TCCP and IR29, under different treatment conditions (Fig. 7). The goal was to investigate how these genes, which play roles in ion homeostasis, ROS scavenging, and stress response, are regulated under salt stress and in response to SeNP supplementation.

Expression analysis of selected salinity stress-responsive genes 24 h after imposition of salt stress, SeNPs, and their combinations in TCCP and IR29. The y-axis represents the Log2 fold change in mRNA expression compared with control (no stress), while x-axis represents treatments. The genes are (a) OSLOL5 (LOC_Os01g42710.1), (b) OsNHX1 (LOC_Os07g47100), (c) OsSOS1 (LOC_Os12g44360), (d) OsHKT1;1 (LOC_Os06g48810), (e) OsHAK20 (LOC_Os02g31940).

In the salt-tolerant TCCP genotype, OSLOL5, NHX1, and HAK20 were significantly upregulated under NaCl stress alone, indicating an active stress response. OSLOL5, a gene involved in ROS scavenging, showed increased expression, suggesting that TCCP efficiently mitigates oxidative damage under salinity59. This aligns with recent studies indicating that selenium nanoparticles enhance antioxidant enzyme activity, reducing ROS accumulation and protecting cellular structures during stress conditions60. Similarly, NHX1 and HAK20 were upregulated, reflecting TCCP’s ability to maintain cellular ion balance by compartmentalizing Na+ into vacuoles and enhancing K+ uptake5,50. SOS1 and HKT1, which are involved in Na + exclusion, also showed increased expression, albeit to a lesser extent, further supporting TCCP’s robust salt tolerance mechanisms10,58. SeNP supplementation modulated these responses in a concentration-dependent manner. At a lower SeNP concentration (10 ppm), the expression of OSLOL5, NHX1, SOS1, and HAK20 decreased relative to NaCl treatment alone, suggesting that SeNPs alleviate salt stress by reducing the need for intense stress responses. In contrast, at higher SeNP concentrations (20 ppm), HKT1 expression was enhanced under salt stress, indicating improved Na+ exclusion from shoots. This result supports the notion idea that SeNPs strengthen stress tolerance mechanisms, particularly in salt-tolerant genotypes, by enhancing ion homeostasis and ROS scavenging50,54.

The salt-sensitive IR29 exhibited a markedly different gene expression pattern compared to TCCP. Under NaCl stress alone, most genes showed slight downregulation or minimal changes, except for OSLOL5, which was moderately upregulated. This suggests that IR29 has a less robust initial response to salt stress, potentially due to weaker ROS scavenging and ion homeostasis mechanisms mechanisms50. However, when SeNPs were combined with NaCl stress, the expression of all five genes was significantly upregulated, particularly at the 20 ppm SeNP concentration (Fig. 7). NHX1 and SOS1, which play key roles in Na+ exclusion and salt tolerance, showed the most pronounced increases in expression under combined NaCl and SeNP treatments. Similarly, HAK20, involved in maintaining Na+/K+ balance, was also upregulated, indicating enhanced K+ acquisition and distribution10,58. These results suggest that SeNPs enhance the salt stress response in IR29, a genotype typically more sensitive to salinity, by boosting the expression of genes critical for ion homeostasis and ROS scavenging11,50. The expression of HKT1, which facilitates Na+ exclusion from shoots, was upregulated in both genotypes under SeNP treatment, but the increase was more pronounced in IR29. This suggests that SeNPs improve Na+ exclusion mechanisms more effectively in salt-sensitive genotypes, potentially due to their greater need for enhanced stress tolerance19,61. These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that selenium nanoparticles improve salt tolerance by enhancing Na+ exclusion and K+ retention, particularly in stress-sensitive crops62.

The upregulation of OSLOL5 in both genotypes, particularly under SeNP treatment, highlights the role of SeNPs in enhancing ROS scavenging. OSLOL5 encodes a protein involved in detoxifying reactive oxygen species (ROS), and its increased expression suggests that SeNPs mitigate oxidative damage caused by salinity11. This aligns with studies showing that exogenous selenium application upregulates antioxidant genes to reduce oxidative stress in plants under salinity34,63. Recent research also indicates that selenium nanoparticles boost the activity of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), which are essential for the ROS detoxification60. Moreover, the enhanced expression of NHX1, SOS1, and HKT1 under SeNP treatment further underscores the role of SeNPs in improving ion homeostasis. NHX1 and SOS1 facilitate Na+ compartmentalization and exclusion, respectively, while HKT1 regulates Na+ transport from shoots to roots, thereby reducing Na+ toxicity in sensitive tissues5,57. The upregulation of HAK20, a potassium transporter, indicates that SeNPs also enhance K+ uptake and distribution, which is essential for osmotic adjustment and enzyme activation under salt stress10. These mechanisms are supported by recent findings that selenium nanoparticles improve ion balance and protect cellular structures under salinity stress62.

The differential gene expression patterns between TCCP and IR29 highlight the potential of SeNPs to enhance stress tolerance in salt-sensitive genotypes. By upregulating key genes involved in ROS scavenging, Na+ exclusion, and K+ uptake, SeNPs provide a multi-faceted approach to mitigating salt stress. These findings aligns with studies demonstrating that selenium application improves salt tolerance in crops such as rice, mustard, and wheat by enhancing antioxidant activity and ion homeostasis50,54,64. The integration of SeNPs into agricultural practices could therefore offer a promising strategy for improving crop resilience in saline environments. A graphical illustration summarizing the proposed mechanism by which LCNF-SeNPs enhance salt tolerance in contrasting rice genotypes is presented in Fig. 8.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the successful synthesis and application of LCNF/SeNPs as a green and sustainable approach to enhancing salt tolerance in rice. The LCNF matrix served as an effective stabilizer for selenium nanoparticles, facilitated their uniform distribution, and improved thermal stability. This highlights the potential of LCNF as a carrier for agricultural nanomaterials. The LCNF/SeNPs composite significantly improved salt stress resilience in rice, particularly in the salt-sensitive IR29 genotype. This improvement was evident through enhanced physiological responses such as chlorophyll preservation, better ion homeostasis, improved shoot growth, and the modulation of key stress-responsive genes (e.g., NHX1, SOS1, and HKT1). These findings underscore the dual role of LCNF/SeNPs in mitigating oxidative damage and improving ion balance under salinity stress.

The novelty of this work lies in integrating LCNFs with SeNPs to create a biocompatible and environmentally friendly composite, addressing nanoparticle stabilization and crop stress management. Unlike conventional methods, this approach provides a sustainable solution for enhancing crop resilience to abiotic stresses, with significant potential for application in saline-affected agricultural systems.

However, this study has some limitations. For instance, the experiments were conducted under controlled conditions, and the long-term effects of LCNF/SeNPs on soil health and crop yield remain unexplored. Future research should focus on field trials to validate the efficacy of LCNF/SeNPs under real-world conditions and explore their application in other crops and stress scenarios. Additionally, the mechanisms underlying the interaction between LCNFs and SeNPs in modulating plant stress responses warrant further investigation.

In conclusion, this study lays a promising foundation for using LCNF/SeNPs in sustainable agriculture. By combining the unique properties of LCNFs and SeNPs, this approach offers a novel strategy for improving crop resilience to salinity and other abiotic stresses, contributing to global food security in the face of climate change.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Two rice genotypes, TCCP and IR29, were selected for this study due to their contrasting responses to salinity stress. TCCP is known for its salt tolerance, while IR29 is highly salt-sensitive. The seeds of both genotypes were obtained from the International Rice Genebank at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. These genotypes were chosen based on their well-documented differences in salt tolerance, providing a clear contrast for assessing the effects of salt stress and potential mitigation strategies40,65.

Preparation of Lignin-containing cellulose nanofiber (LCNF)

To prepare the LCNF, unbleached softwood fiber was processed using a high-speed rotor grinder at a 2% weight consistency. The pulp was then ground for two hours in an ultrafine friction grinder (MKCA6-2, Masuko Sangyo, Kawaguchi, Japan) with a disk gap of 90 μm. The suspension was homogenized twice at 208 MPa pressure using an M-110EH-30 microfluidics machine (Microfluidics Corp., Newton, MA, USA).

Preparation of LCNF-Selenium nanoparticles (LCNF/SeNPs)

LCNF-selenium nanoparticles (LCNF/SeNPs) were synthesized using a microwave-assisted green approach, offering both efficiency and environmentally friendliness. Sodium selenite (Na₂SeO₃, 99.8%) and ascorbic acid were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). A 2% weight LCNF suspension was mixed with Na₂SeO₃ (2 mmol) to form a solution, followed by the addition of 1.0% ascorbic acid to facilitate the reduction of selenium ions to selenium nanoparticles. The hydroxyl and carboxyl groups on the surface of the LCNF help immobilize the selenium ions. The mixture was then subjected to microwave heating at 120 °C for 1 h, accelerating the reduction process and ensuring the uniform formation of selenium nanoparticles. After the reaction, the LCNF/SeNPs composite was separated and washed to remove unreacted materials.

Characterizations of LCNF/SeNPs

The SeNPs and LCNF/SeNPs composites were characterized using several techniques. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) was conducted in Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) mode. X-ray diffraction analysis was performed with a PANalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) over a 2θ range from 4° to 80°. The morphology of the LCNF and LCNF/SeNPs samples was examined using a Quanta 3D DualBeam FEG FIB-SEM and a JEM 1400 Transmission Electron Microscope (Peabody, MA, USA). Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of LCNF and LCNF/SeNPs samples was conducted in a nitrogen atmosphere using a Q50 Analyzer (TA Instruments Inc., New Castle, DE, USA), with a temperature range from 30 °C to 600 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

Impact of LCNF/SeNPs on seed germination of rice genotypes

Healthy, uniform seeds of both rice genotypes were surface sterilized using a 5% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min, followed by thorough rinsing with distilled water. The seeds were then placed in Petri dishes lined with filter paper and germinated at 25 °C. The filter papers were saturated with varying concentrations of LCNF/SeNPs (5, 10, 20, and 40 mg/mL), NaCl (50, 100, 150, and 200 mM), combinations of LCNF/SeNPs and NaCl, or distilled water as a negative control. Each treatment was replicated three times, with 20 seeds per replication. Germination was monitored daily for four days, with the the emergence of a 2 mm radicle used as the criterion for germination.

Evaluation of salinity tolerance

Salinity tolerance screening was conducted in a greenhouse at the Louisiana State University Agricultural Center Central Research Station in Baton Rouge, LA, USA (30°24′41.7″ N, 91°10′21.8″ W), where temperatures ranged from 25 to 29 °C. The screening procedure consisted of three steps: (a) seed pre-germination, (b) stress treatment, and (c) data collection.

The seeds were surface sterilized as described earlier and then pre-germinated. Once germinated, the seeds were transferred to pots containing a sand-soil mixture in the greenhouse. At the three-leaf stage, seedlings were exposed to 150 mM NaCl (pH 5.0) and SeNPs at 10 and 20 ppm concentrations, both separately and in combination with 150 mM NaCl. The salinity treatment lasted for 3 to 5 days. Control plants were grown in distilled water without any treatment. A factorial design with three replications was used, with ten seedlings per genotype per replication. Five seedlings with uniform growth per genotype were selected for data collection in each replication. Trait means were calculated by averaging the measured values of these five seedlings.

Visual salt injury score (SIS)

The plants’ response to salinity stress was assessed using a Visual Salt Injury Score (SIS) 6 days after salinization (DPS) based on the IRRI standard evaluation system66. SIS scores ranged from 1 to 9, where a score of 1 indicated no injury, a score of 3 was given to seedlings with minor leaf damage and stunted growth compared to the control, a score of 5 represented stressed plants with stunted growth, green rolled leaves, and whitish tips, a score of 7 indicated plants with only a green stem and dried leaves, and a score of 9 was assigned to completely dead plants. SIS values were based on observations of 10 seedlings per genotype across three replicates, and the final score for each genotype was calculated as the mean of all individual scores.

Chlorophyll content (SPAD Reading)

Chlorophyll content was measured using a SPAD 502 chlorophyll meter (Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Aurora, IL, USA). Readings were taken from the middle portion of the second youngest leaf of both control and stressed rice genotypes at 4 and 6 days after exposure to salinity stress. Final scores were calculated as the average of these readings.

Growth parameters

Growth parameters were evaluated by measuring the shoot and root lengths of each genotype 8 days after exposure to stress. Shoot length was measured from the base of the plant to the tip of the longest leaf, while root length was measured from the base of the plant to the tip of the root.

Measurement of Na+ and K+

Na⁺ and K⁺ concentrations in each genotype’s root and shoot tissues were determined following the published method66. Plant samples were dried at 65 °C for 2 days and ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Approximately 500 mg of shoot tissue and 200 mg of root tissue were digested with 5 mL of nitric acid and 3 mL of hydrogen peroxide at 152–155 °C for 3 h. The digested tissue was then diluted to a final volume of 12.5 mL. Na⁺ and K⁺ concentrations were measured using a flame photometer (Jenway PFP7 model; Bibby Scientific Ltd., Staffordshire, UK), and final concentrations were determined from a standard curve. The Na⁺/K⁺ ratio was calculated by dividing the Na⁺ concentration by the K⁺ concentration in both root and shoot tissues.

Expression analysis of genes associated with salt tolerance

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to assess the expression of five selected genes in rice genotypes under control, saline, and combined SeNP and saline stress conditions. Leaf samples were collected at two time points (0 and 24 h after stress exposure), immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C. Three biological replicates were used for total RNA extraction with Trizol reagent for each treatment. RNA quality was assessed using a 1.2% agarose gel, and RNA quantification was performed with an ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA samples were treated with PerfeCTa DNase 1 (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA), and high-quality RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the iScript™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Gene sequences were obtained from the Phytozome database67, and qRT-PCR primers were designed using Primer Quest (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) (Table 3). EF1α (LOC_Os03g08010) was used as an internal standard for normalization. qRT-PCR was performed in three technical replicates using cDNA from biological replicates along with iTaq™ Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA)68. Gene expression levels were quantified using the 2−∆∆CT method69.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.3.2 70. To assess the differences between treatment groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using the aov function in R. Where applicable, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were made using the Tukey HSD test to identify significant differences between groups.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Change history

30 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33941-4

References

Yamori, W. Improving photosynthesis to increase food and fuel production by biotechnological strategies in crops. J. Plant. Biochem. Physiol. 1, 113 (2013).

Muthayya, S., Sugimoto, J. D., Montgomery, S. & Maberly, G. F. An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption: global rice production, consumption, and trade. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1324, 7–14 (2014).

Ray, D. K., Mueller, N. D., West, P. C. & Foley, J. A. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE. 8, e66428 (2013).

Shrivastava, P. & Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 22, 123–131 (2015).

Munns, R. & Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 59, 651–681 (2008).

Bartholomé, J. et al. Genomic selection for salinity tolerance in Japonica rice. PLoS ONE. 18, e0291833 (2023).

Ullah, A., Bano, A. & Khan, N. Climate change and salinity effects on crops and chemical communication between plants and plant growth-promoting microorganisms under stress. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 618092 (2021).

Saberi Riseh, R., Ebrahimi-Zarandi, M., Tamanadar, E., Moradi Pour, M. & Thakur, V. K. Salinity stress: toward sustainable plant strategies and using plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria encapsulation for reducing it. Sustainability 13, 12758 (2021).

Flowers, T. J. & Flowers, S. A. Why does salinity pose such a difficult problem for plant breeders? Agric. Water Manag. 78, 15–24 (2005).

Reddy, I. N. B. L., Kim, B. K., Yoon, I. S., Kim, K. H. & Kwon, T. R. Salt tolerance in rice: focus on mechanisms and approaches. Rice Sci. 24, 123–144 (2017).

Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxid. (Basel). 9, 681 (2020).

Mittler, R. ROS are good. Trends Plant. Sci. 22, 11–19 (2017).

Gill, S. S. & Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 48, 909–930 (2010).

You, J. & Chan, Z. ROS regulation during abiotic stress responses in crop plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 6, 1092 (2015).

Das, K. & Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2, 53 (2014).

El-Badri, A. M. et al. Selenium and zinc oxide nanoparticles modulate the molecular and morpho-physiological processes during seed germination of Brassica napus under salt stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 225, 112695 (2021).

Samynathan, R. et al. A recent update on the impact of nano-selenium on plant growth, metabolism, and stress tolerance. Plants 12, 853 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Tissue-specific regulation of Na+ and K+ transporters explains genotypic differences in salinity stress tolerance in rice. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 1361 (2019).

Wang, R. et al. The rice high-affinity potassium transporter1;1 is involved in salt tolerance and regulated by an MYB-type transcription factor. Plant. Physiol. 168, 1076–1090 (2015).

Rubio, F., Nieves-Cordones, M., Horie, T. & Shabala, S. Doing ‘business as usual’ comes with a cost: evaluating energy cost of maintaining plant intracellular K+ homeostasis under saline conditions. New. Phytol. 225, 1097–1104 (2020).

Horie, T., Hauser, F. & Schroeder, J. I. HKT transporter-mediated salinity resistance mechanisms in Arabidopsis and monocot crop plants. Trends Plant. Sci. 14, 660–668 (2009).

Sunarpi et al. Enhanced salt tolerance mediated by AtHKT1 transporter-induced Na+ unloading from xylem vessels to xylem parenchyma cells. Plant. J. 44, 928–938 (2005).

Martínez-Atienza, J. et al. Conservation of the salt overly sensitive pathway in rice. Plant. Physiol. 143, 1001–1012 (2007).

Møller, I. S. et al. Shoot Na+ exclusion and increased salinity tolerance engineered by cell type-specific alteration of Na+ transport in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 21, 2163–2178 (2009).

Badshah, I. et al. Biogenic titanium dioxide nanoparticles ameliorate the effect of salinity stress in wheat crop. Agron. (Basel). 13, 352 (2023).

Mustafa, N. et al. Exogenous application of green titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) to improve the germination, physiochemical, and yield parameters of wheat plants under salinity stress. Molecules 27, 4884 (2022).

Avestan, S., Ghasemnezhad, M., Esfahani, M. & Byrt, C. S. Application of nano-silicon dioxide improves salt stress tolerance in strawberry plants. Agron. (Basel). 9, 246 (2019).

Feng, Y. et al. Effects of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) on growth, photosynthesis, antioxidant activity and distribution of mineral elements in wheat (Triticum aestivum) plants. Plants 11, 1894 (2022).

Gerbreders, V., Krasovska, M., Sledevskis, E., Mihailova, I. & Mizers, V. Co3O4 nanostructured sensor for electrochemical detection of H2O2 as a stress biomarker in barley: Fe3O4 nanoparticles-mediated enhancement of salt stress tolerance. Micromachines (Basel). 15, 311 (2024).

Hassanpouraghdam, M. B. et al. Foliar application of cerium oxide-salicylic acid nanoparticles (CeO2:SA nanoparticles) influences the growth and physiological responses of Portulaca oleracea L. under salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5093 (2022).

Siddiqui, S. A. et al. Effect of selenium nanoparticles on germination of hordéum vulgáre barley seeds. Coatings 11, 862 (2021).

Gupta, M. & Gupta, S. An overview of selenium uptake, metabolism, and toxicity in plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 2074 (2017).

Farooq, M. A. et al. Mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin-selenium nanoparticles on arsenic-induced stress in Brassica napus. Environ. Pollut. 292, 118473 (2022).

El-Badri, A. M. et al. Mitigation of the salinity stress in rapeseed (Brassica Napus L.) productivity by exogenous applications of bio-selenium nanoparticles during the early seedling stage. Environ. Pollut. 310, 119815 (2022).

Mellinas, C., Jiménez, A. & Garrigós, M. D. C. Microwave-assisted green synthesis and antioxidant activity of selenium nanoparticles using Theobroma cacao L. bean shell extract. Molecules 24, 4048 (2019).

Kustov, L. & Vikanova, K. Synthesis of metal nanoparticles under microwave irradiation: get much with less energy. Met. (Basel). 13, 1714 (2023).

Kumar, A., Sood, A., Maiti, P. & Han, S. S. Lignin-containing nanocelluloses (LNCs) as renewable and sustainable alternatives: prospects, and challenges. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 41, 100830 (2023).

Pradhan, D., Jaiswal, A. K. & Jaiswal, S. Emerging technologies for the production of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass. Carbohydr. Polym. 285, 119258 (2022).

Gregorio, G. B., Senadhira, D. & Mendoza, R. D. Screening rice for salinity tolerance. IRRI Discussion Paper Series No. 22. Manila (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute. (1997).

Walia, H. et al. Comparative transcriptional profiling of two contrasting rice genotypes under salinity stress during the vegetative growth stage. Plant. Physiol. 139, 822–835 (2005).

Zuluaga, R. et al. Cellulose microfibrils from banana Rachis: effect of alkaline treatments on structural and morphological features. Carbohydr. Polym. 76, 51–59 (2009).

Ewulonu, C. M., Liu, X., Wu, M. & Huang, Y. Ultrasound-assisted mild sulphuric acid ball milling Preparation of lignocellulose nanofibers (LCNFs) from sunflower stalks (SFS). Cellulose 26, 4371–4389 (2019).

Abouzeid, R. E., Khiari, R., El-Wakil, N. & Dufresne, A. Current state and new trends in the use of cellulose nanomaterials for wastewater treatment. Biomacromolecules 20, 573–597 (2019).

Abouzeid, R. E., Khiari, R., Beneventi, D. & Dufresne, A. Biomimetic mineralization of three-dimensional printed alginate/TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibril scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules 19, 4442–4452 (2018).

Saeed, M. et al. Assessment of antimicrobial features of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) using Cyclic voltammetric strategy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 19, 7363–7368 (2019).

Nasiri, S. et al. Modified scherrer equation to calculate crystal size by XRD with high accuracy, examples Fe2O3, TiO2 and V2O5. Nano Trends. 3, 100015 (2023).

Vahdati, M. & Tohidi Moghadam, T. Synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles-lysozyme nanohybrid system with synergistic antibacterial properties. Sci. Rep. 10, 510 (2020).

Neysanian, M. et al. Comparative efficacy of selenate and selenium nanoparticles for improving growth, productivity, fruit quality, and postharvest longevity through modifying nutrition, metabolism, and gene expression in tomato; potential benefits and risk assessment. PLoS ONE. 16, e0250192 (2021).

Sharma, D., Afzal, S. & Singh, N. K. Nanopriming with phytosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles for promoting germination and starch metabolism in rice seeds. J. Biotechnol. 336, 64–75 (2021).

Feng, R., Wei, C. & Tu, S. The roles of selenium in protecting plants against abiotic stresses. Environ. Exp. Bot. 87, 58–68 (2013).

Subramanyam, K., Du Laing, G. & Van Damme, E. J. M. Sodium selenate treatment using a combination of seed priming and foliar spray alleviates salinity stress in rice. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 116 (2019).

Shaban, A. S. et al. Comparison of the Morpho-physiological and molecular responses to salinity and alkalinity stresses in rice. Plants 13, 60 (2023).

Rakgotho, T. et al. Green-synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles mitigate salt stress in Sorghum bicolor. Agriculture 12, 597 (2022).

Ran, M., Wu, J., Jiao, Y. & Li, J. Biosynthetic selenium nanoparticles (Bio-SeNPs) mitigate the toxicity of antimony (Sb) in rice (Oryza sativa L.) by limiting Sb uptake, improving antioxidant defense system and regulating stress-related gene expression. J. Hazard. Mater. 470, 134263 (2024).

Ismail, A. M. & Horie, T. Genomics, physiology, and molecular breeding approaches for improving salt tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 68, 405–434 (2017).

Shekari, F., Abbasi, A. & Mustafavi, S. H. Effect of silicon and selenium on enzymatic changes and productivity of dill in saline condition. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 16, 367–374 (2017).

Astaneh, R. K., Bolandnazar, S., Nahandi, F. Z. & Oustan, S. The effects of selenium on some physiological traits and K, Na concentration of Garlic (Allium sativum L.) under NaCl stress. Inf. Process. Agric. 5, 156–161 (2018).

Lanza, M. G. D. B. & Reis, A. R. dos. Roles of selenium in mineral plant nutrition: ROS scavenging responses against abiotic stresses. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 164, 27–43 (2021).

Zhang, L. M. et al. Early transcriptomic adaptation to Na2CO3 stress altered the expression of a quarter of the total genes in the maize genome and exhibited shared and distinctive profiles with NaCl and high pH stresses. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 55, 1147–1165 (2013).

Das, A., Pal, S., Chakraborty, N., Hasanuzzaman, M. & Adak, M. K. Regulation of reactive oxygen species metabolism and oxidative stress signaling by abscisic acid pretreatment in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings through sub1A QTL under salinity. Plant. Stress. 11, 100422 (2024).

Golldack, D. et al. Characterization of a HKT-type transporter in rice as a general alkali cation transporter. Plant. J. 31, 529–542 (2002).

Das, A., Pal, S., Hasanuzzaman, M., Adak, M. K. & Sil, S. K. Mitigation of aluminum toxicity in rice seedlings using biofabricated selenium nanoparticles and nitric oxide: synergistic effects on oxidative stress tolerance and sulfur metabolism. Chemosphere 370, 143940 (2025).

Hussain, S., Ahmed, S., Akram, W., Li, G. & Yasin, N. A. Selenium seed priming enhanced the growth of salt-stressed Brassica rapa L. through improving plant nutrition and the antioxidant system. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1050359 (2023).

Sarkar, R. D. & Kalita, M. C. Green synthesized se nanoparticle-mediated alleviation of salt stress in field mustard, TS-36 variety. J. Biotechnol. 359, 95–107 (2022).

Gregorio, G. B., Senadhira, D. & Mendoza, R. D. IRRI Discussion Paper Series No. 22. International Rice Research Institute. P.O. Box 933, (1099).

Jones, J. B. Jr & Case, V. W. Sampling, handling, and analyzing plant tissue samples. In: (ed Westerman, R. L.) Soil Testing and Plant Analysis, Book Series 3, Soil Science Society of America, Madison, 389–427. (1990).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186 (2012).

Subudhi, P. K., Garcia, R. S., Coronejo, S. & Tapia, R. Comparative transcriptomics of rice genotypes with contrasting responses to nitrogen stress reveals genes influencing nitrogen uptake through the regulation of root architecture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5759 (2020).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL (2021). https://www.R-project.org/

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Grant No. 2023-68012-39002). This manuscript is approved for publication by the Director of Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station, USA as manuscript number 2025-306-40104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K.S. conceptualized, designed, and supervised the whole study. A.S.S. and R.A. conducted the experiment, data analysis, and generated all the figures and tables. Q.W. supervised the synthesis of nanoparticles. A.S.S., R.A, Q.W. and P.K.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error, where an incorrect version of Figure 6 was published. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaban, A.S., Abouzeid, R., Wu, Q. et al. Lignin-containing cellulose nanofiber-selenium nanoparticle hybrid enhances tolerance to salt stress in rice genotypes. Sci Rep 15, 14173 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98906-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98906-z